Abstract

Background

We examined rapid response in obese patients with binge-eating disorder (BED) in a clinical trial testing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral weight loss (BWL).

Method

Altogether, 90 participants were randomly assigned to CBT or BWL. Assessments were performed at baseline, throughout and post-treatment and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Rapid response, defined as ≥70% reduction in binge eating by week four, was determined by receiver operating characteristic curves and used to predict outcomes.

Results

Rapid response characterized 57% of participants (67% of CBT, 47% of BWL) and was unrelated to most baseline variables. Rapid response predicted greater improvements across outcomes but had different prognostic significance and distinct time courses for CBT versus BWL. Patients receiving CBT did comparably well regardless of rapid response in terms of reduced binge eating and eating disorder psychopathology but did not achieve weight loss. Among patients receiving BWL, those without rapid response failed to improve further. However, those with rapid response were significantly more likely to achieve binge-eating remission (62% v. 13%) and greater reductions in binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology and weight loss.

Conclusions

Rapid response to treatment in BED has prognostic significance through 12-month follow-up, provides evidence for treatment specificity and has clinical implications for stepped-care treatment models for BED. Rapid responders who receive BWL benefit in terms of both binge eating and short-term weight loss. Collectively, these findings suggest that BWL might be a candidate for initial intervention in stepped-care models with an evaluation of progress after 1 month to identify non-rapid responders who could be advised to consider a switch to a specialized treatment.

Keywords: Binge eating, cognitive behavior therapy, eating disorders, obesity, treatment, weight loss

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED), a research category in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and likely a formal diagnosis in DSM-5 (www.dsm5.org), is characterized by recurrent binge eating accompanied by feelings of loss of control and marked distress in the absence of inappropriate weight-compensatory behaviors. BED is a prevalent (Hudson et al. 2007), stable (Pope et al. 2006) problem strongly associated with obesity, elevated psychiatric/medical co-morbidity and psychosocial impairment (Hudson et al. 2007; Grilo et al. 2009). BED has diagnostic validity (Wonderlich et al. 2009) and differs from obesity, other eating disorders and other forms of disordered eating (Allison et al. 2005; Grilo et al. 2008, 2010).

Although some effective treatments have been identified for BED (Wilson et al. 2007; Reas & Grilo, 2008), even in studies with the best outcomes, a substantial proportion of patients do not achieve abstinence from binge eating and most achieve little weight loss (Wilfley et al. 2002; Grilo et al. 2005a, b; Wilson et al. 2010). Thus, it is important to find ways to predict BED patients’ response to treatments as this may lead to more effective decision making about treatment prescriptions. Some recent studies have identified potential patient predictors of treatment outcome for BED (Hilbert et al. 2007; Masheb & Grilo, 2007, 2008; Wilson et al. 2010) but, in general, it has proven to be difficult to identify reliable pretreatment predictors of outcome for BED and other eating disorders (Wilson et al. 2007).

One promising predictor of treatment outcome may be initial treatment response (Ilardi & Craighead, 1994). Several treatment studies of bulimia nervosa (BN) identified early rapid response as a significant predictor of positive outcomes (Wilson et al. 1999, 2002; Agras et al. 2000; Fairburn et al. 2004; Walsh et al. 2006; Sysko et al. 2010). In a series of studies, Grilo and colleagues replicated and extended the rapid response findings in several ways to BED (Grilo et al. 2006; Grilo & Masheb, 2007; Masheb & Grilo, 2007). Rapid response, defined as 65–70% reductions in binge eating by the fourth treatment week based on receiver operating curves, was ‘reliably’ observed in the different treatment studies. Rapid response was associated with significantly greater binge-eating remission rates and reductions in eating disorder psychopathology (Grilo et al. 2006; Grilo & Masheb, 2007; Masheb & Grilo, 2007) and statistically greater weight loss (Grilo et al. 2006; Grilo & Masheb, 2007). Perhaps most importantly for conceptual (‘treatmentspecificity’) and clinical (‘treatment prescription’) reasons, rapid response had different prognostic significance and time courses across different treatments for BED. Grilo et al. (2006) found that among patients receiving cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy (without CBT), if rapid response occurred it was well sustained throughout the course of treatment. However, among patients without a rapid response, in the case of CBT, a pattern of subsequent improvement was observed, whereas in the case of pharmacotherapy only, no further improvement was observed. This later finding for the prognostic significance of non-rapid response to pharmacotherapy only was replicated in a study of BN (Sysko et al. 2010). Masheb & Grilo (2007) found that rapid response had different prognostic significance for CBT and behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatments delivered via guided self-help (i.e. CBTgsh and BWLgsh). BED patients receiving CBTgsh, but not BWLgsh, derived similar benefits regardless of whether they experienced rapid response, although they failed to lose significant weight. In contrast, BED patients receiving BWLgsh who had a rapid response were more likely to achieve binge-eating remission than patients without a rapid response plus they achieved significantly greater (but modest) weight loss than patients receiving CBTgsh. Safer & Joyce (2011) extended the findings regarding the prognostic significance of rapid response to two other treatments for BED, although the frequency and significance were greater for dialectical behavior therapy than for a control group therapy.

Masheb & Grilo (2007) cautiously noted that their findings, if replicated, raised the possibility that, rather than starting with CBT or CBTgsh (per the National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004 recommendation), BED patients could be advised to start with BWL and evaluate progress after 1 month of treatment to determine whether to switch to a more specialized treatment such as CBT. The Masheb & Grilo (2007) studies tested guided self-help 12-week versions of CBT and BWL and those findings may not generalize to traditional, more intensive CBT and BWL treatments or to longer-term outcomes. Thus, the present study examined rapid response in obese patients with BED who participated in a controlled study testing the effectiveness of CBT and BWL delivered in traditional intensive 6-month group formats following established manualized protocols and followed-up for 12 months after completing treatments. We hypothesized that rapid response would predict overall superior outcomes but would have different prognostic significance for CBT and BWL. Specifically, we predicted relatively few differences between rapid and non-rapid responders to CBT but expected that, in BWL, rapid responders would have significantly greater improvements in binge eating and weight loss than non-rapid responders.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 90 patients who met DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) BED criteria and participated in a randomized controlled trial comparing CBT and BWL (Grilo et al. 2011). Eligibility also required age 18–60 years and body mass index (BMI) ≥30. Exclusionary criteria were medical conditions (e.g. diabetes or thyroid problems) that influence eating/weight, severe psychiatric conditions requiring alternative treatments (psychosis, bipolar disorder), concurrent treatments or medications for eating/weight problems and pregnancy. The study received Yale Institutional Review Board approval. All participants provided written informed consent.

In total, 120 consecutively evaluated participants were randomized to one of three treatments (CBT, BWL or sequential CBT + BWL). Only the 90 participants receiving CBT and BWL interventions were eligible for this study; the sequential CBT + BWL condition was 4 months longer, not directly relevant and therefore excluded. Participants had a mean age of 44.89 (s.d. = 9.48) years and mean BMI 38.65 (s.d. = 5.70). Altogether, 62% (n = 56) of participants were female, 85.6% (n = 77) attended/finished college and 77.8% (n = 70) were Caucasian, 13.3% (n = 12) were African American, 5.6% (n = 5) were Hispanic and 3.3% (n = 3) were ‘other’ ethnicity.

Diagnostic assessments and repeated measures

Diagnostic and assessment procedures were performed by trained doctoral-level research clinicians. DSM-IV psychiatric disorder diagnoses, including BED, were based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I/P; First et al. 1996) and eating disorder psychopathology was assessed with the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993). Inter-rater reliability, determined using n = 42 cases, was excellent, with reliability coefficients of 0.99 for binge-eating frequency and range 0.87–0.97 for EDE subscales. Interrater reliability for SCID-I/P diagnoses was good, with κ coefficients range 0.57–1.0 ; κ = 1.0 for BED.

The EDE Interview (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993)

The EDE interview is semi-structured and investigator-based, with well-established reliability (Grilo et al. 2004) and validity (Grilo et al. 2001a, b). The interview was administered at baseline and was re-administered at post-treatment and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups after treatment completion. The EDE focuses on the previous 28 days except for diagnostic items, which are rated for DSM-IV duration stipulations. The EDE assesses the frequency of objective bulimic episodes (OBEs); i.e. binge eating defined as unusually large quantities of food with a subjective sense of loss of control, which corresponds to the DSM-IV definition of binge eating. The EDE also comprises four subscales (dietary restraint, eating concern, weight concern and shape concern) and a total global score reflecting associated eating disorder psychopathology. Items are rated on 7-point forced-choice scales (range 0–6), with higher scores reflecting greater severity/frequency.

Weight and height

Weight and height were measured at baseline and again immediately prior to beginning treatment using a medical balance beam scale. Weight was measured every 2 weeks throughout treatment, at post-treatment and at 6- and 12-month follow-ups. BMI was calculated from these measurements.

Self-monitoring

Overeating behaviors, including OBEs, were assessed prospectively throughout the course of treatment by self-monitoring using daily record sheets (Wilson & Vitousek, 1999; Grilo et al. 2001a, b). Each daily record inquired whether participants had any OBEs and, if so, how many. Daily records contained the definition of OBEs, which was reviewed with participants at the start of treatment. Participants were provided with stapled packets of seven blank daily record sheets for each week. Research clinicians met briefly with participants every week to collect self-monitoring and check them for completeness. Participants were reminded each time of the importance of self-monitoring on a daily basis.

Randomization to treatment conditions

Randomization to the treatment conditions was performed without any restriction or stratification using a computer-generated sequence. Randomization was determined after completion of all assessments and formal acceptance into the study. Randomization assignment was kept blinded from the participants until the start of treatment.

Treatments

Five therapists (doctoral-level psychologists with experience treating patients with obesity and eating disorders) delivered the treatments. Therapists received intensive training in both CBT and BWL and were monitored (via session audiotapes and weekly supervision) by the investigators throughout treatment courses. Treatments were delivered in groups sessions co-led by two therapists. During the study, each therapist delivered both treatments. CBT was administered in 16 group 60-min sessions over a 24-week period following a manualized protocol (Fairburn et al. 1993), considered ‘the treatment-of-choice’ for BED (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004) and previously delivered effectively in groups (Wilfley et al. 2002). BWL was administered in 16 group 60-min sessions over a 24-week period following the manualized LEARN Program for Weight Management (Brownell, 2000). This widely used BWL (Foster et al. 2003) has been used previously in BED trials (Devlin et al. 2005).

Statistical analyses

Defining rapid response

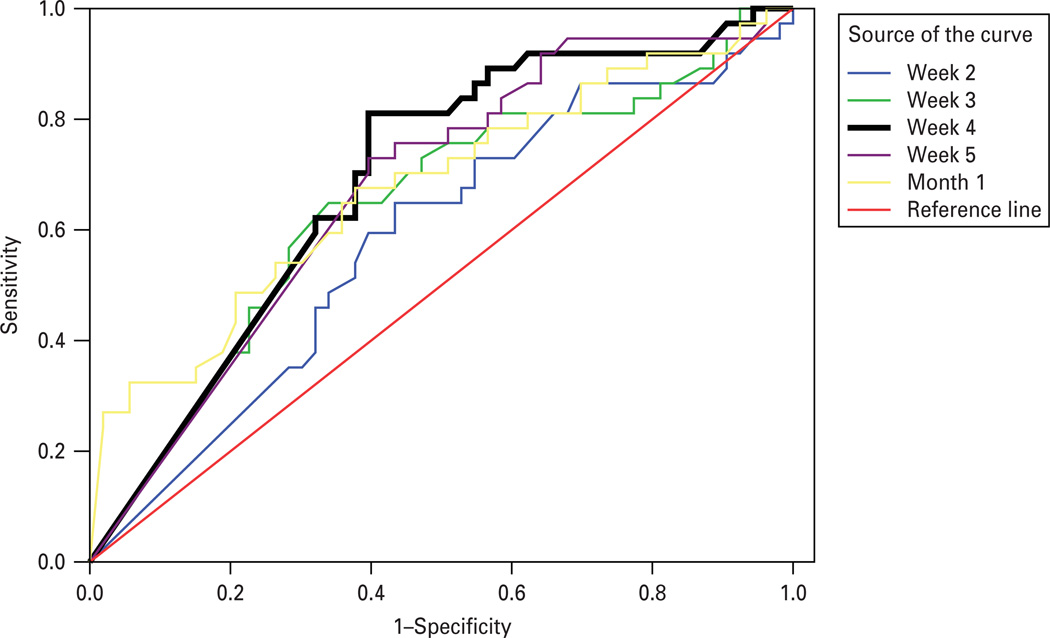

The definition of rapid response was informed by previous studies on rapid response using signal detection methods in studies with BED and BN (Grilo et al. 2006). We constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves using percentage reduction in binge eating during the first 5 weeks (determined using daily self-monitoring) to predict the primary post-treatment outcome of remission from binge eating (determined using the EDE interview). Percentage reduction in binge eating from baseline at each week was calculated together with the total percentage reduction from baseline observed during the first 5 weeks (as well as for month one, given the possibility of weekly fluctuations). ROC curves allow testing the accuracy of the different measures (percentage reductions in binge eating during early stages of treatment) for correctly predicting the post-treatment outcome of binge-eating remission. Fig. 1 shows the ROC curves.

Fig. 1.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves predicting binge remission post-treatment based on percentage reduction in binge eating (determined by prospective daily self-monitoring) observed at weeks 1–5 and for total of month 1. ROC curve for the fourth week is most predictive and is shown in bold. The fourth week ROC had AUC of 0.688 (s.e. = 0.057), with 95% CI 0.578–0.799, p = 0.002). A 70% reduction in binge-eating frequency by the fourth week maximized sensitivity (0.79) and specificity (0.39) for predicting binge-eating remission (determined by the Eating Disorder Examination at post-treatment). Diagonal segments are produced by ties.

The ROC curve for percentage reduction at the fourth week emerged as most predictive based on the overall area under the curve (AUC) as well as specifically on the portion of the curve of most interest (i.e. to have lower false positive rates) (Streiner & Cairney, 2007). The AUC under this curve equaled 0.688 (s.e. = 0.057), with 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.578–0.799 ; p = 0.002 for the null hypothesis that true area = 0.5. An AUC of 0.70 reflects moderate accuracy (Streiner & Cairney, 2007). Inspection of this ROC revealed that a reduction of ≥70% in binge eating by the fourth week maximized sensitivity and 1 − specificity (0.811 and 0.396, respectively) and therefore this served as our definition of rapid response.

Comparison of participants with and without rapid response

Participants classified as rapid responders were compared with those without a rapid response on demographic variables, psychiatric co-morbidity and clinical eating/weight variables at baseline using χ2 analyses for categorical variables and analyses of variance (ANOVA) for continuous measures.

Rapid response and treatment outcomes

Analyses, performed for all randomized participants (intent to treat), compared rapid responders and non-rapid responders on primary outcomes using two complementary approaches. First, ‘remission’ from binge eating [zero binges (OBEs) during the previous 28 days determined by EDE interview] was defined separately at post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups; for treatment drop-outs and instances of missing data, baseline data were carried forward. Binge-eating remission rates between rapid and non-rapid responders were compared using χ2 analyses. Second, rapid and non-rapid-responders were compared on continuous measures of binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology and percentage BMI loss using mixed models (SAS proc mixed) that use all available data throughout the study without imputation. Binge-eating frequency (OBEs during previous 28 days on EDE interview) and EDE global scores (reflecting overall eating disorder psychopathology) at baseline, post-treatment, 6- and 12-month follow-ups) were analysed using mixed models. Mixed models were also used to compare rapid versus non-rapid responders on ‘percentage BMI loss’ (based on BMI measured at baseline, every 2 weeks throughout treatments, post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups). For each of these outcome variables, a mixed model was fitted with rapid response status (rapid versus non-rapid) and treatment condition (CBT versus BWL) as between-subject factors, time as a within-subject factor (with levels representing the relevant assessment time points) and the interactions among rapid response, treatment and time.

Distributions of data were examined and transformations were applied, if necessary, to satisfy model assumptions (e.g. binge-eating frequency data were log-transformed). For each model, different variance–covariance structures were evaluated and the best-fitting structure was selected based on the Schwartz Bayesian criterion.

Results

Rapid response and patient characteristics

Of the 90 patients randomized, 51 (56.7%) showed a rapid response, defined in this study as ≥70% reduction in binge eating by the fourth treatment week. Rapid response was observed in 67% (n = 30/45) of participants receiving CBT and 47% (n = 21/45) of those receiving BWL (χ2(1) = 3.66, p = 0.07).

As summarized in Table 1, rapid responders did not differ significantly from participants who did not show rapid response in gender, ethnicity, education or age of onset of BED, although rapid responders were older than non-rapid responders. Rapid responders did not differ from non-rapid responders in the frequency of lifetime mood disorders (major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder) or substance use disorders, although rapid responders did have a lower rate of anxiety disorders. Rapid responders did not differ significantly from non-rapid responders on pretreatment levels of binge eating, associated eating disorder psychopathology (EDE subscales or global score) or BMI. In addition, the two treatment groups (CBT and BWL) did not differ (Grilo et al. 2011), nor did the four groups (i.e. rapid and non-rapid responders within CBT and BWL treatments) differ on these baseline variables.

Table 1.

Demographic, psychiatric, and clinical characteristics of participants with a rapid response versus without a rapid response

| Rapid response (N = 51) |

No rapid response (N = 39) |

Test statistic | p value | Effect size |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (s.d.) | 47.94 (8.57) | 40.90 (9.23) | F(1, 88) = 13.97 | 0.000 | 0.137 |

| Female, n (%) | 28 (54.9%) | 28 (71.8%) | χ2(1) = 2.68 | 0.101 | 0.173 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | χ2(2) = 0.15 | 0.928 | 0.041 | ||

| Caucasian | 39 (76.5%) | 31 (79.5%) | |||

| African–American | 7 (13.7%) | 5 (12.8%) | |||

| Hispanic–American or ‘other ’ | 5 (9.8%) | 3 (7.7%) | |||

| Education, n (%) | χ2(2) = 0.49 | 0.782 | 0.074 | ||

| College | 25 (49%) | 22 (56.4%) | |||

| Some college | 18 (35.3%) | 12 (30.8%) | |||

| High school or less | 8 (15.7%) | 5 (12.8%) | |||

| DSM-IV diagnoses, lifetime, n (%) | |||||

| Mood disorders | 23 (45.1%) | 21 (53.8%) | χ2(1) = 0.68 | 0.411 | 0.087 |

| Anxiety disorders | 17 (33.3%) | 22 (56.4%) | χ2(1) = 4.79 | 0.029 | 0.231 |

| Substance use disorders | 11 (21.6%) | 10 (25.6%) | χ2(1) = 0.21 | 0.651 | 0.048 |

| Age onset BED, mean (s.d.) | 27.94 (14.10) | 23.51 (9.59) | F(1, 88) = 2.84 | 0.096 | 0.031 |

| Clinical characteristics, mean (s.d.) | |||||

| Binge-eating days/month (EDE) | 14.0 (5.4) | 13.0 (6.0) | F(1, 88) = 0.79 | 0.378 | 0.009 |

| Binge-eating episodes/month (EDE) | 15.5 (7.3) | 15.0 (9.5) | F(1, 88) = 0.06 | 0.810 | 0.001 |

| Dietary restraint (EDE) | 1.6 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.2) | F(1, 88) = 0.67 | 0.416 | 0.008 |

| Eating concern (EDE) | 2.0 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.2) | F(1, 88) = 0.00 | 0.984 | 0.000 |

| Weight concern (EDE) | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.6 (1.1) | F(1, 88) = 1.13 | 0.291 | 0.013 |

| Shape concern (EDE) | 2.9 (0.8) | 3.2 (0.9) | F(1, 88) = 2.98 | 0.088 | 0.033 |

| Global Score (EDE) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.9) | F(1, 88) = 1.18 | 0.281 | 0.013 |

| Body mass index | 38.3 (5.5) | 39.1 (6.0) | F(1, 88) = 0.35 | 0.555 | 0.004 |

BED, Binge-eating disorder ; EDE, Eating Disorder Examination interview.

Test statistic = χ2 for categorical variables and F value from analyses of variance for dimensional variables. p values are for two-tailed tests. Effect size measures are φ coefficients for categorical variables and partial η2 for dimensional variables.

Rapid response and binge-eating remission outcomes

Overall, 56.7% (n = 51/90) of participants showed a rapid response and the following overall rates of binge-eating remission were observed over time: 41.1% (n = 37/90) at post-treatment ; 42.2% (n = 38/90) at 6-month follow-up; 43.3% (n = 39/90) at 12-month follow-up. Across treatments, participants with a rapid response were significantly more likely than those without a rapid response to achieve a remission from binge eating at each time point: at post-treatment [58.8% (n = 30/51) v. 17.9% (n = 7/39); χ2(1) = 15.25, p < 0.001 (φ coefficient = 0.412)] ; 6-month follow-up [54.9% (n = 28/51) v. 25.6% (n = 10/39); χ2(1) = 7.76, p < 0.005 (φ coefficient = 0.294)] ; 12-month follow-up [58.8% (n = 30/51) v. 23.1% (n = 9/39); χ2(1) = 11.50, p < 0.001 (φ coefficient = 0.357)].

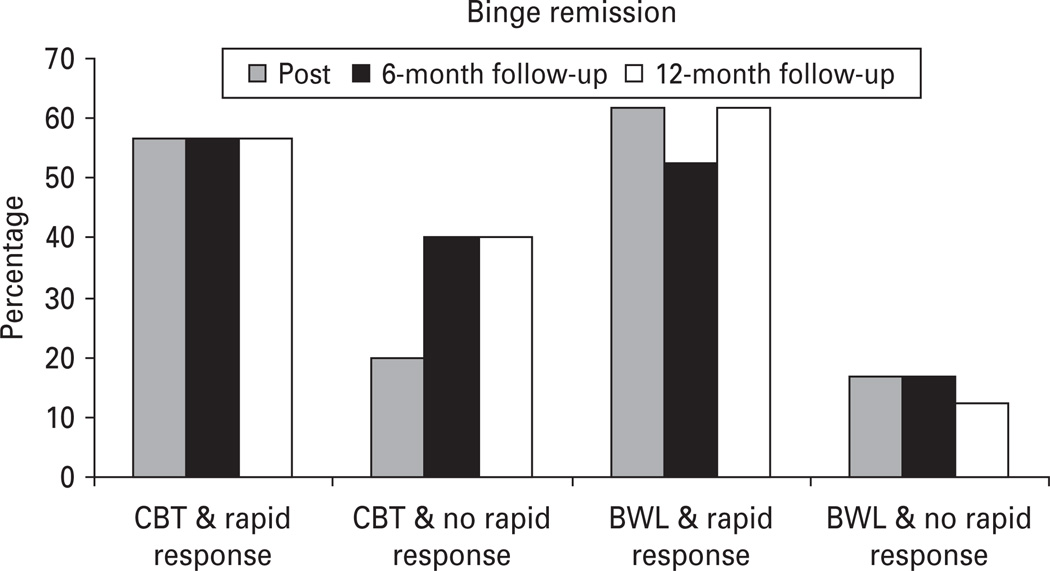

Fig. 2 summarizes the proportion of participants with versus without a rapid response shown separately across CBT and BWL treatments who achieved binge-eating remission at post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Among the 45 participants receiving CBT, those with a rapid response were significantly more likely than non-rapid responders to achieve remission from binge eating at post-treatment [56.7% v. 20.0%; χ2(1) = 5.45, p = 0.02, φ coefficient = 0.348] but did not differ in binge-eating remission rates at either 6-month follow-up [56.7% v. 40.0; χ2(1) = 1.11, p = 0.29, φ coefficient = 0.157] or at 12-month follow-up [56.7% v. 40.0%; χ2(1) = 1.11, p = 0.29, φ coefficient = 0.157]. In contrast, among the 45 participants receiving BWL, those with a rapid response were significantly more likely to achieve remission from binge eating at all three time points as follows : at post-treatment [61.9% v. 16.7%; χ2(1) = 9.75, p = 0.002, φ coefficient = 0.465] ; 6-month follow-up [52.4% v. 16.7 ; χ2(1) = 6.43, p = 0.01, φ coefficient = 0.378] ; 12-month follow-up [61.9% v. 12.5%; χ2(1) = 11.93, p < 0.001, φ coefficient = 0.515].

Fig. 2.

Percentage of participants with rapid response versus without rapid response shown separately across cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatments who achieved remission from binge eating at post-treatment, 6-month and 12-month follow-up assessments. Data are for all randomized patients (n = 90) in intent-to-treat analyses (baseline carried forward method for instances of missing data). Rapid response is defined as ≥70% reduction in frequency of binge-eating episodes by the fourth treatment week based on daily prospective self-monitoring. Binge-eating remission is defined as zero binge episodes for the previous month based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview.

Rapid response and time course of binge-eating frequency

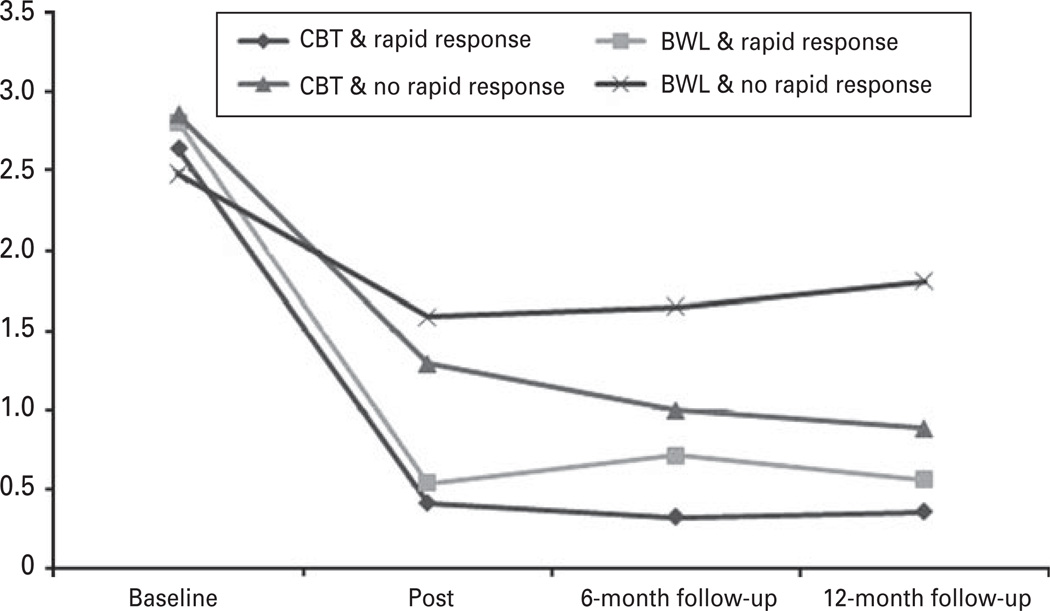

Fig. 3 shows the monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response at the major assessment points (baseline, post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-up) shown separately across CBT and BWL treatments. Data shown are based on estimated marginal means, derived from mixed-models analyses. Mixed models revealed significant main effects for rapid response [F(1, 76.8) = 19.48, p < 0.0001], treatment [F(1, 76.8) = 4.01, p < 0.05] and for time [F(3, 68.5) = 146.29, p < 0.0001] and a significant three-way interaction [F(3, 68.5) = 3.01, p = 0.036]. Follow-up tests revealed that, among participants receiving CBT, rapid responders had significantly lower binge-eating frequencies than non-rapid responders at post-treatment [F(1, 64.4) = 5.95, p = 0.018] but no longer differed at either 6-month [F(1, 75.5) = 3.54, p = 0.064] or 12-month [F(1, 71.6) = 2.55, p = 0.115] follow-up. In contrast, follow-up tests revealed that, among participants receiving BWL, rapid responders had significantly lower binge-eating frequencies at all three post-treatment assessments as follows: at post-treatment [F(1, 65) = 9.78, p = 0.003] ; 6-month follow-up [F(1, 73.3) = 8.21, p = 0.005] ; 12-month follow-up [F(1, 71.6) = 16.86, p = 0.0001].

Fig. 3.

Monthly frequency of binge eating by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response during the major assessment points through the 12-month follow-up shown separately across cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatments. The data shown are based on estimated marginal means (derived from mixed models analyses) for all n = 90 participants.

Rapid response and time course of eating disorder psychopathology

Mixed models testing eating disorder psychopathology (EDE global score) outcomes revealed significant main effects for rapid response [F(1, 81.6) = 5.01, p < 0.03] and for time [F(3, 200) = 42.95, p < 0.0001] and a significant three-way interaction [F(3, 200) = 2.93, p = 0.03]. Follow-up tests revealed no significant differences by rapid response status for participants receiving CBT at any time point. In contrast, among participants receiving BWL, rapid and non-rapid responders did not differ significantly on EDE global scores at post-treatment [F(1, 194) = 1.55, p = 0.21] but rapid responders had significantly lower EDE global scores at 6-month follow-up [F(1, 164) = 6.27, p = 0.01] and 12-month follow-up [F(1, 171) = 3.87, p = 0.05].

Rapid response and percentage BMI loss outcomes

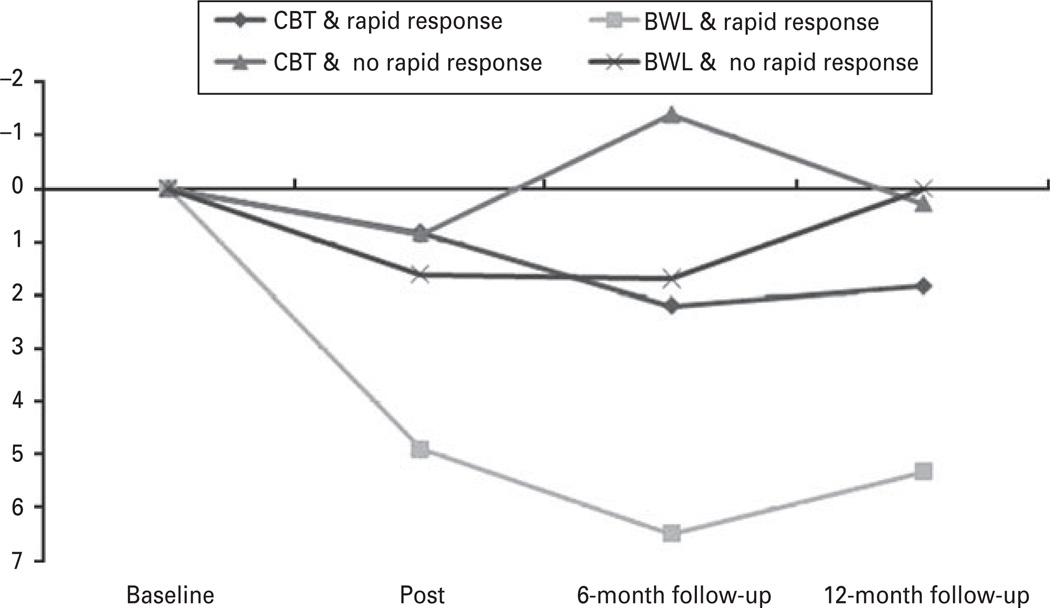

Fig. 4 summarizes the course of percentage BMI loss by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response during the major assessment points through the 12-month follow-up shown separately across CBT and BWL treatments. The data shown (only for the major assessment points) are based on estimated marginal means, derived from mixed-models analyses at the major outcome assessment time points. Mixed-models analyses of percentage BMI loss (every 2 weeks during treatment, post-treatment and 6- and 12-month follow-up) revealed significant main effects for rapid response (higher percentage BMI loss than non-rapid responders) [F(1, 83.3) = 5.63, p = 0.02], for treatment (BWL had higher percentage BMI loss than CBT) [F(1, 83.3) = 8.32, p = 0.005] and for time [F(1, 70.9) = 9.85, p = 0.0025]. Post-hoc comparisons of BMI data between rapid responders and non-rapid responders at major assessment points revealed that, for those receiving CBT, no significant differences were observed; whereas for those receiving BWL, rapid responders had significantly lower BMI at post-treatment [F(1, 102) = 4.88, p = 0.03], 6-month follow-up [F(1, 99.6) = 6.41, p = 0.01] and 12-month follow-up [F(1, 102) = 6.50, p = 0.01].

Fig. 4.

Percentage body mass index loss by participants with rapid response versus without rapid response during the major assessment points through the 12-month follow-up shown separately across cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and behavioral weight loss (BWL) treatments. The data shown are based on estimated marginal means (derived from mixed models analyses) for all n = 90 participants.

Discussion

Rapid response (defined as ≥70% reduction in binge eating by the fourth week of treatment based on findings from ROC curves) characterized 57% of participants (67% of those receiving CBT and 47% of those receiving BWL) and was unrelated to baseline binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology, BMI and most psychiatric variables. Overall, rapid response predicted greater improvements across outcomes but had different prognostic significance and distinct time courses for CBT and BWL through 12-month follow-up. Patients who received CBT did comparably well regardless of rapid response in terms of reduced binge eating (i.e. although rapid responders had significantly less binge eating at post-treatment than non-rapid responders, differences were no longer significant by 6- and 12-month follow-up) and eating disorder psychopathology but did not achieve weight loss. Among patients receiving BWL, those without rapid response failed to show subsequent improvements. However, those with rapid response were significantly more likely to achieve binge-eating remission (62% v. 13%) and had greater reductions in binge-eating frequency, eating disorder psychopathology and weight loss through 12-month follow-up.

Our rapid response definition based on ROC curves very closely parallels findings from previous studies in BED (Grilo et al. 2006; Grilo & Masheb, 2007; Masheb & Grilo, 2007; Safer & Joyce, 2011). Collectively, these findings speak to the reliability of this treatment process. Rapid response demonstrated the same prognostic significance and time course for CBT delivered via group methods in this study as previously reported for CBT delivered by guided self-help (Grilo & Masheb, 2007; Masheb & Grilo, 2007) and via traditional individual therapy sessions (Grilo et al. 2006). Among patients receiving CBT, those with a rapid response were likely to sustain positive outcomes, except for weight loss, through 12-month follow-up (e.g. 57% were abstinent from binge eating). Importantly, those without a rapid response to CBT showed a subsequent pattern of continued improvement in binge eating and in associated psychopathology that by 12-month follow-up no longer differed significantly from rapid responders to CBT. We note that the binge-eating remission rate of 40% observed for the non-rapid responders to CBT at 12-month follow-up is higher than acute treatment (i.e. short-term studies) remission rates reported by nearly all medication studies for BED (see Reas & Grilo, 2008). Collectively, these findings speak to the validity and predictive utility of the rapid response construct in CBT for BED. Furthermore, the clinical implication of these findings is that CBT should be continued even in the absence of an early treatment response, rather than switching to alternative treatments (Eldredge et al. 1997).

Among patients receiving BWL, those without rapid response failed to show subsequent improvements. This finding replicates the finding that non-rapid response to BWL signals poor prognosis, initially reported by Masheb & Grilo (2007), and extends it to 12-months post-treatment. Non-response to BWL has important prognostic significance. These findings parallel those reported for non-rapid response to pharmacotherapy for BED (Grilo et al. 2006) and for BN (Sysko et al. 2010), where non-rapid-responders were unlikely to derive any further benefit from continuing antidepressants and therefore suggesting the need to switch or try alternative treatments. In contrast, among patients receiving BWL, those with rapid response were significantly more likely to achieve binge-eating remission (62%), improvements in eating disorder psychopathology and weight loss than non-rapid responders through 12-month follow-up. Conceptually, these findings represent strong evidence for the specificity of treatment effects.

The practical clinical implications of these findings are that BWL might be a candidate for initial intervention stepped-care treatment. BWL is likely more readily disseminated and practised by a wider range of health-care providers than specialized therapies such as CBT. An evaluation of progress following 1 month of treatment could identify rapid responders to the BWL who would likely benefit from continuing whereas non-rapid-responders could be advised to consider a switch to another treatment, such as CBT. Currently, CBTgsh is recommended as a starting point in evidence-based stepped-care treatment (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2004; Wilson et al. 2010). CBTgsh is briefer than BWL and has been shown to be cost-effective (Lynch et al. 2010), but has little effect on weight (Grilo & Masheb, 2005; Wilson et al. 2010). An advantage for BWL, however, is its relatively standard implementation in groups, which makes for efficiency. Rapid responders to BWL in our study showed modest but significant weight loss compared with non-responders (and to CBT) at all assessment points. Nevertheless, it is well established that weight re-gain is common following BWL treatments for obese persons (regardless of BED) and that the advantage to BWL observed in our study may not last long term (Wilson et al. 2010).

Rapid response does not appear to be associated with most patient characteristics or pretreatment clinical severity. Consistent with findings from previous studies of rapid response in BED (Grilo et al. 2006; Grilo & Masheb, 2007), rapid responders to treatment did not differ significantly from non-rapid responders on most demographic factors and clinical characteristics. Previous studies (Masheb & Grilo, 2007) have reported that rapid responders to CBTgsh and BWL had lower levels of eating disorder psychopathology but – like our findings here – observed no differences on most baseline characteristics. Unlike the previous studies, we found that rapid responders were significantly older than non-rapid responders. However, age at presentation for treatment for BED has not been identified as a reliable predictor of outcome (Masheb & Grilo, 2007). We also observed no differences between rapid responders and non-rapid responders in lifetime rates of mood disorders or substance use disorders, although rapid responders were significantly less likely to have anxiety disorders. Interestingly, the one previous study that found an isolated significant finding regarding psychiatric co-morbidity (Grilo & Masheb, 2007) reported that rapid responders were more likely to have an anxiety disorder. Collectively, these findings suggest that rapid response to treatment is not easily predicted in BED patients based on pretreatment characteristics.

Given that rapid response is not easily predicted in BED patients based on pretreatment characteristics, this construct is unlikely to simply reflect ‘less complicated patients doing well’. It is important to note that participants in this study had high levels of eating disorder psychopathology and psychiatric co-morbidity. Overall, 49% of the participants had at least one mood disorder and 43% had at least one anxiety disorder. These rates of psychiatric co-morbidity are similar to those of studies of CBT and psychological treatments for BED (Wilfley et al. 2002; Grilo et al. 2005a, b) but are higher than those for most medication trials for BED (see Reas & Grilo, 2008). Thus, the findings regarding rapid response and its durability over 12-month follow-up cannot be attributed to low severity or exclusion of poor prognosis patients due to psychiatric co-morbidity.

We note the following strengths and potential limitations of our study. Our methods involved complementary multi-method assessments with documented strengths (Grilo et al. 2001a, b). Since we used one method (daily self-monitoring) to determine rapid response and different methods (reliably administered EDE interviews and measured height and weights) to determine treatment outcomes, we reduced a potential method artefact or tautology that might occur by using the same measure to assess both initial response and later outcome. A related issue concerning self-monitoring is its potential for producing reactivity. Self-monitoring, when used specifically in treatment, is thought to be an essential ingredient in diverse behavioral treatments (Wilson & Vitousek, 1999). We cannot determine whether some of the observed effects might simply reflect some degree of reactivity to self-monitoring although we emphasize that (1) the differential findings for CBT versus BWL and (2) the persistence of the outcomes for 12-months after discontinuation of treatments both argue against this. In terms of potential limitations, we note that our findings cannot generalize past 12-months of follow-up. The one study with longer-term follow-up of BWL for BED found that some of the benefits in binge eating and weight loss diminished by 24 months (Wilson et al. 2010). We also note that the amount of weight loss achieved was modest and finding ways to produce greater weight loss in this patient group remains a pressing challenge for researchers (Wilson et al. 2007). In addition, BWL was delivered by specialist doctoral-level research clinicians and it remains uncertain whether similar outcomes would be achieved by generalist clinicians who typically deliver BWL in non-university settings. Our findings are also limited to treatment-seeking obese persons with BED who responded to advertisements for treatment studies at a medical school and thus may not generalize to BED patients who seek treatment at different types of clinics or to obese patients without BED who seek BWL for obesity, or to patient groups of different ethnic/racial or educational background.

In summary, rapid response to CBT and BWL treatments for BED demonstrated positive prognostic significance through 12-month follow-up. Although rapid response predicted greater improvements across outcomes, rapid response had different prognostic significance and distinct time courses for CBT versus BWL. Patients receiving CBT did comparably well regardless of rapid response in terms of reduced binge eating and eating disorder psychopathology but did not achieve weight loss. In contrast, among patients receiving BWL, those without rapid response failed to show subsequent improvements. However, those with rapid response achieved durable improvements including high rates of binge-eating remission, significant reductions in eating disorder psychopathology and weight loss through 12-month follow-up.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK49587 (Dr Grilo). Preparation of this manuscript was also partly supported by NIH grant K24 DK070052 (Dr Grilo).

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- Agras WS, Crow SJ, Halmi KA, Mitchell JE, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. Outcome predictors for the cognitive behavior treatment of bulimia nervosa : data from a multisite study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1302–1308. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison KC, Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Stunkard AJ. Binge eating disorder and night eating syndrome: a comparative study of disordered eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:1107–1115. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD. The LEARN Program for Weight Management 2000. Dallas, TX: American Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Goldfein JA, Petkova E, Jiang H, Raizman PS, Wolk S, Mayer L, Carino J, Bellace D, Kamenetz C, Dobrow I, Walsh BT. Cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine as adjuncts to group behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder. Obesity Research. 2005;13:1077–1088. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge KL, Agras WS, Arnow B, Telch CF, Bell S, Castonguay L, Marnell M. The effects of extending cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating disorder among treatment non-responders. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;21:347–352. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(1997)21:4<347::aid-eat7>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Wilson GT, Stice E. Early change in treatment predicts outcome in bulimia nervosa. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2322–2324. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination (12th edition) In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating : Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Marcus MD, Wilson GT. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for binge eating and bulimia nervosa : a comprehensive treatment manual. In: Fairburn CG, Wilson GT, editors. Binge Eating : Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. pp. 361–404. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders – Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, Version 2.0) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, McGuckin BG, Brill C, Mohammed BS, Szapary PO, Rader DJ, Edman JS, Klein S. A randomized trial of a low-carbohydrate diet for obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;348:2082–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Hrabosky JI, White MA, Allison KC, Stunkard AJ, Masheb RM. Overvaluation of shape and weight in binge eating disorder and overweight controls : refinement of a diagnostic construct. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:414–419. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. A randomized controlled comparison of guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy and behavioral weight loss for binge-eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:1509–1525. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM. Rapid response predicts binge eating and weight loss in binge-eating disorder : findings from a controlled trial of orlistat with guided self-help cognitive behavioral therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:2537–2550. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, Barry DT. Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:80–85. doi: 10.1002/eat.10238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL. Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder : a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Biological Psychiatry. 2005a;57:1193–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, White MA. Significance of overvaluation of shape and weight in binge-eating disorder : comparative study with overweight and bulimia nervosa. Obesity. 2010;18:499–504. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. A comparison of different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001a;69:317–322. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Different methods for assessing the features of eating disorders in patients with binge eating disorder : a replication. Obesity Research. 2001b;9:418–422. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder : a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biological Psychiatry. 2005b;57:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT. Rapid response to treatment for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:602–613. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, Gueorguieva R, White MA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge eating disorder : a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1037/a0025049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM. DSM-IV psychiatric disorder comorbidity and its correlates in binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:228–234. doi: 10.1002/eat.20599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert A, Saelens B, Stein R, Mockus D, Welch R, Matt G, Wilfley DE. Pretreatment and process predictors of outcome in interpersonal and cognitive behavioral psychotherapy for binge eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:645–651. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;61:348–358. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilardi SS, Craighead WE. The role of nonspecific factors in cognitive-behavior therapy for depression. Clinical Psychology : Science and Practice. 1994;1:138–156. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch FL, Striegel-Moore RH, Dickerson JF, Perrin N, Debar L, Wilson GT, Kraemer HC. Cost-effectiveness of guided self-help treatment for recurrent binge eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:322–333. doi: 10.1037/a0018982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Rapid response predicts treatment outcomes in binge eating disorder : implications for stepped care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:639–644. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masheb RM, Grilo CM. Examination of predictors and moderators for self-help treatments of binge-eating disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:900–904. doi: 10.1037/a0012917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Clinical Excellence. London: NICE; 2004. Eating Disorders – Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, Related Eating Disorders. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Lalonde JK, Pindyck LJ, Walsh BT, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, McElroy SL, Rosenthal N, Hudson JI. Binge eating disorder : a stable syndrome. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:2181–2183. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reas DL, Grilo CM. Review and meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy for binge-eating disorder. Obesity. 2008;16:2024–2038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer DL, Joyce EE. Does rapid response to two group psychotherapies for binge eating disorder predict abstinence? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL, Cairney J. What’s under the ROC? An introduction to receiver operating characteristics curves. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;52:121–128. doi: 10.1177/070674370705200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysko R, Sha N, Wang Y, Duan N, Walsh BT. Early response to antidepressant treatment in bulimia nervosa. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:999–1005. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh BT, Sysko R, Parides MK. Early response to desipramine among women with bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2006;39:72–75. doi: 10.1002/eat.20209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfley DE, Welch RR, Stein RI, Spurrell E, Cohen L, Saelens B, Dounchis JZ, Frank MA, Wiseman CV, Matt GE. A randomized comparison of group cognitive behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of overweight individuals with binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:713–721. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.8.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Fairburn CG, Agras WS, Walsh BT, Kraemer H. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for bulimia nervosa : time course and mechanisms of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Grilo CM, Vitousek KM. Psychological treatments of eating disorders. American Psychologist. 2007;72:199–216. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Loeb KL, Walsh BT, Labouvie E, Petkova E, Lin X, Waternaux C. Psychological versus pharmacological treatments of bulimia nervosa : predictors and processes of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:451–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Vitousek KM. Self-monitoring in the assessment of eating disorders. Psychological Assessment. 1999;11:480–489. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, Bryson SW. Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67:94–101. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Gordon KH, Mitchell JE, Crosby RD, Engel SG. The validity and clinical utility of binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:687–705. doi: 10.1002/eat.20719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]