Abstract

The Eph receptor tyrosine kinases and their ephrin partners compose a large and complex family of signaling molecules involved in a wide variety of processes in development, homeostasis, and disease. The complexity inherent to Eph/ephrin signaling derives from several characteristics of the family. First, the large size and functional redundancy/compensation by family members presents a challenge in defining their in-vivo roles. Second, the capacity for bidirectional signaling doubles the potentially complexity, since every member has the ability to act both as a ligand and a receptor. Third, Ephs and ephrins can utilize a wide array of signal transduction pathways with a tremendous diversity of cell biological effect. The daunting complexity of Eph/ephrin signaling has increasingly prompted investigators to resort to multiple technological approaches to gain mechanistic insight. Here we review recent progress in the use of advanced mouse genetics in combination with proteomic and transcriptomic approaches to gain a more complete understanding of signaling mechanism in vivo. Integrating insights from such disparate approaches provides advantages in continuing to advance our understanding of how this multifarious group of signaling molecules functions in a diverse array of biological contexts.

1. Introduction

The Ephs are the largest family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) in vertebrates, and are composed by A- and B- subfamilies. Originally isolated from an Erythropoietin-Producing Hepatocellular carcinoma, Eph receptors are bound by EPh Receptor INteracting (ephrin) proteins of the A-type and B-type with varying intra and inter- subfamily affinities. A-type Ephs bind with ephrin-As, except for EphA4 which can also bind with all B-type ephrins; A-type ephrins bind with A-type Ephs, except for ephrin-A5 which can also bind with EphB2. Eph/ephrin signaling plays marquee roles in the nervous system where it controls numerous aspects of neuronal connectivity, but is also critical in a wide variety of other contexts, including angiogenesis, craniofacial development, intestinal homeostasis, cancer, and skeletal development/homeostasis. The cell biological effects of activation of Eph/ephrin signaling are abundant and often idiosyncratic; Eph/ephrin signaling initiates cell adhesion and cell repulsion, oncogenesis and tumor suppression, cell migration and mitogenesis. It is becoming increasingly clear that the molecular mechanisms utilized to achieve such varied outcomes are even more extensive. The Eph/ephrin family has the capacity for bidirectional signaling, such that either Ephs or ephrins can serve as receptors to transduce a signal into the cell in which they are expressed. In the forward direction, Eph/ephrin signaling can activate a large number of signal transduction pathways that are both kinase dependent and independent and at least two molecular mechanisms by which reverse signaling occurs have been identified.

One of the principles emerging from this signaling maze is that biological context is absolutely crucial when deciphering Eph/ephrin signaling function. For this reason, genetic approaches dissecting signaling mechanism in-vivo constitute a keystone methodology. For example, mouse genetics has been heavily used to interrogate the relative requirements for forward and reverse signaling. Unfortunately, interpretation of these results is not always entirely straightforward, and these methods have been fraught with technical challenges. Further, genetic ablation is not sufficient on its own to comprehend extensive signaling networks and therefore needs to be buttressed by large scale phosphoproteomic and transcriptomic methodologies. So far, most attempts at utilizing these approaches have focused on signaling activated by B-type ephrins and as such, our emphasis in this review is on Eph/ephrin-B signaling. We focus on efforts to utilize mouse genetics to define signaling mechanism and discuss recent advances in proteomic and transcriptomic approaches to define signaling networks.

2. Utilizing mouse genetics to define signaling mechanism

2.1. Forward signaling

Signaling mutations in EphB2 provided the first evidence for bidirectional signaling, and since this time the EphB2 receptor signaling mechanism has been extensively interrogated by mouse genetics approaches. Null loss of function of EphB2 results in phenotypes affecting a wide variety of developmental processes (Table 1.), especially when compounded with mutations in semi-redundant family members EphB3 and EphB1. A subset of these phenotypes were observed when mutations disrupting only forward signaling were analyzed, indicating that EphB2 serves as a receptor in those contexts, and suggesting it functions as a ligand in others. Early studies indicated that EphB2/EphB3 signaling is critical for axon guidance of the anterior commissure, corpus callosum, and for formation of the secondary palate [1, 2]. Since this time, genetic perturbations of ephrins have identified the signaling partners in each of these contexts (reviewed in [3]). For example, a mutation disrupting forward signaling in which the intracellular domain of EphB2 has been replaced with LacZ results in a cleft palate phenotype similar to the one observed in EphB2−/− null mutant embryos[4]. Null mutations of ephrin-B1 display a corresponding cleft palate phenotype, whereas point mutations affecting ephrin-B1’s reverse signaling function do not [5–7]. These results therefore indicate that ephrin-B1 forward signaling through EphB2 and EphB3 controls palatogenesis. Approaches such as these have been used extensively to define the receptor/ligand and forward/reverse signaling relationships (Table 1).

Table 1. Genetically defined receptor/ligand pairs in mice.

This table lists ephrin-B/Eph receptor/ligand pairs for which symmetrical phenotypes have been reported. This is not an exhaustive list of Eph/ephrin phenotypes, but includes only those phenotypes for which mouse genetics evidence supports receptor/ligand relationships.

| Ligand | Receptor | Signal Direction | Phenotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ephrin-B1 | EphB2/B3 | Forward | Cleft palate | [2, 4–7] |

| EphB2 EphB1/B2 |

PDZ-reverse | Agenesis of the corpus callosum | [2, 5, 19] | |

| EphB2/B3 | Forward (Kinase independent) | cell positioning in intestinal epithelium | [42, 53] | |

| EphB2/B3 | Forward (Kinase dependent) | Cell proliferation in intestinal epithelium | [52, 53] | |

| Ephrin-B2 | EphB4 EphB2/B3 |

Forward PDZ-reverse* |

Angiogenesis | [20, 21, 23, 24, 58] |

| EphB2 EphA4 |

pY- and PDZ- Reverse | Reduced LTP | [26, 59, 60] | |

| EphB3 | PDZ- reverse | Lung development | [61] | |

| EphA4 EphB4 |

Reverse | Anterior Commissure Defects | [1, 11, 30] | |

| EphB2/B3 | Forward Reverse |

Urorectal Development | [31] | |

| EphB2/B3 | Reverse | Ventral cochlear nucleus (VCN) axon guidance defects | [62] | |

| Ephrin-B3 | EphA4 | Forward | CST axon guidance | [10, 12] |

| EphB1/B2/B3 | pY reverse | Hippocampal mossy fiber axon pruning defects | [27] | |

| EphB2 EphA4 |

Reverse | Reduced LTP | [59, 60] | |

| EphB1 | Forward | Agenesis of the corpus callosum | [1, 19] |

Given the size and redundancy inherent to the Eph/ephrin signaling family, and the diversity of biochemical signaling response possible, it has been suggested that individual highly specific signaling effectors may be unlikely to exist. Rather a complex network of effectors with redundant functions could transduce signaling. EphA4 has been the subject of a series of genetic studies characterizing downstream signaling pathways therefore providing a strong understanding of forward signaling mechanism. Targeted null mutation of EphA4 or its signaling partner ephrin-B3 caused defects in axon guidance of the anterior commissure, corticospinal tract (CST), and spinal interneuron axons, and disrupts the central pattern generator (CPG) resulting in a rabbit-like hopping gait [8–10]. By generating a targeted knock-in mutation specifically disrupting kinase activity (EphA4KD/KD), it was established that EphA4 forward signaling is required for CST formation and CPG activity, whereas kinase independent reverse signaling controls axon guidance of the anterior commissure [11]. Correspondingly, disrupting ephrin-B3 reverse signaling did not cause CST phenotypes, indicating a role for forward signaling and not reverse [12]. Interestingly, a mutation (EphA4EE/EE) with constitutive activation of kinase activity behaved relatively normally with respect to CST formation, indicating that although kinase activity is fully activated in these mutants, ligand binding triggers other critical steps, such as receptor clustering, providing a multi-step activation model for Eph/ephrin signaling [13].

Compelling genetic and biochemical evidence has identified the RacGAP α2-Chimaerin as a critical signaling effector mediating EphA4 function in CST axon guidance and CPG function. Physical interaction between EphA4 and α2-Chimaerin was observed, and α2-Chimaerin−/− null mice displayed CST abnormalities and a rabbit-like hopping gait [14–16]. Compound mutations of the signaling adaptor proteins Nck1 and Nck2 within the nervous system, also led to abnormal CST axon guidance and defects in the CPG [17]. These proteins have long been known to bind and be phosphorylated by Eph receptors, can also interact with α2-Chimaerin, strongly implicating them in downstream signaling by EphA4. Although not described in detail, it was reported that Nck1−/−; Nck2+/− mutants also display phenotypes outside the CNS, suggesting that Nck adaptor function may be relevant in mediating Eph receptor function elsewhere [17]. These findings support the existence of Eph signaling effectors with specific unique function. In addition these signaling partners appear to have receptor and context-specificity; whereas α2-Chimaerin is a critical effector of CST axon guidance, it was not reported to be broadly involved in other Eph-dependent processes.

2.2.1 PDZ-dependent reverse signaling

The c-terminus of B-type ephrins bind PDZ-domain containing proteins constitutively, and upon binding of EphB signaling partners activate a PDZ-dependent reverse signal (reviewed in [3, 18]). The in vivo requirements for this signaling mechanism have been examined by generating targeted point mutations disrupting the C-terminal valine of B-type ephrins, a residue that has been shown to be required for PDZ-protein binding.

EfnB1 ΔV/ΔV embryos exhibited complete agenesis of the corpus callosum due to loss of axonal reception of a repulsive cue from EphB2 guidepost glia but do not display craniofacial anomalies [5]. Whereas null mutations in EphB2−/− also resulted in agenesis of the corpus callosum, disruption of forward signaling ability by this receptor did not lead to this phenotype indicating that reverse signaling by ephrin-B1, but not forward signaling by EphB2, is required [2, 19]. Therefore bidirectional signaling between this receptor/ligand pair is not at play, but rather ephrin-B1 acts uniquely as a receptor in this context.

Ephrin-B2 expression in the vascular endothelium of arteries is required for embryonic angiogenesis and its disruption resulted in embryonic lethality around E10.5 [20, 21]. Analysis of efnB2ΔV/ΔV embryos indicated that PDZ-dependent reverse signaling was necessary for post-natal remodeling of the lymphatic vasculature, but embryos survived well beyond the early requirement for ephrin-B2 in embryonic angiogenesis [22]. More recently, a re-examination of efnB2ΔV/ΔV embryos revealed alterations in retinal and tumor angiogenesis. In both cases a reduced number of endothelial tip cells with fewer filopodial extensions were observed indicating that PDZ-dependent reverse signaling plays a role in angiogenic sprouting [23]. Interestingly, ephrin-B2 PDZ-dependent reverse signaling was required for proper internalization and phosphorylation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR2), which is necessary for normal tip cell function. A concurrently published study showed that ephrin-B2 also regulates internalization of VEGFR3, and loss of function of ephrin-B2 disrupts VEGFR downstream signal transduction through the small GTPase Rac1, Akt, and ERK/MAPK pathways [24]. Ephrin-B2 regulation of VEGFR internalization was also observed in the lymphatic system, suggesting that this mechanism may also underlie lymphatic phenotypes in efnB2ΔV/ΔV mice [24]. Although mutations abrogating forward signaling by EphB4 have not yet been published, the survival of efnB2ΔV/ΔV embryos through early angiogenesis indicates an important role for forward signaling, suggesting that this may be a context where simultaneously bidirectional signaling is at play.

2.3. Phosphorylation-dependent reverse signaling

Upon engagement by the EphB extracellular domain, B-type ephrins are phosphorylated on several conserved intracellular tyrosines providing a binding site for the SH2-domain containing adaptor Grb4 (reviewed in [3]). Phosphorylation dependent reverse signaling has its most significant roles in the development and function of the nervous system. Targeted point mutations in mice that replace all of the intracellular tyrosines with non-phosphorylateable phenylalanine, (efnb16F/6F, or efnb25F/5F) did not identify an in vivo role for tyrosine phosphorylation of these proteins outside of the nervous system [5, 25]. This is not likely to be explained as a consequence of functional redundancy, since efnb16F/6F; efnb25F/5F compound mutants were viable and healthy and did not display any overt phenotypes in skeletal or vascular development (Bush and Soriano, unpublished observations). Further, efnb3−/− mutant mice have not been reported to display phenotypes outside of the nervous system. Mutating four of five ephrin-B2 tyrosines to phenylalanine and Tyr333 to leucine (efnb25Y/5Y) resulted in a mild lymphatic phenotype likely as a consequence of perturbation of the C-terminal PDZ-binding domain [22]. Interestingly, efnb25Y/5Y mice displayed defects in hippocampal Long Term Potentiation (LTP), but not Long Term Depression (LTD), two phenomena underlying learning and memory [26]. PDZ-dependent reverse signaling by ephrin-B2, was required for both forms of long-term plasticity. It has not been reported whether efnb25F/5F mutant mice exhibit defects in LTP.

Ephrin-B3 utilizes phosphorylation-dependent reverse signaling for the postnatal pruning of mossy fiber axons [27]. Each of the receptors EphB1, EphB2, and EphB3 play a role in this process, as mutations in any one had mild defects in mossy fiber axon pruning and triple mutant EphB1−/− EphB2−/−; EphB3−/−, displayed more severe defects, resembling Efnb3−/− or efnb35F/5F mice. Activation of phosphorylation-dependent reverse signaling induces binding of Grb4 which serves to recruit p21 activating kinase (Pak1) and the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Dock180 to activate downstream Rac/Cdc42. Whether the kinase activity of Eph receptors is also required for mossy fiber axon pruning is not known, since kinase-inactive mutants have not been reported in this context. Therefore, whether this process requires bidirectional signaling, or requires reverse signaling uniquely, is not clear.

Recently, compound efnb1−/−; efnb2−/−; efnb3−/− mutant brains were shown to display a dramatic cortical neuron migration phenotype similar to Reeler (Reln−/−) mutant mice [28]. Reelin is an extracellular protein that regulates neuronal migration and layering by binding to lipoprotein receptors to initiate phosphorylation of Dab1. Interestingly, efnb2 or efnb3 were both shown to interact genetically with Reln+/−, and B-type ephrins co-immuno-precipitate with Reelin and Dab-1. Activation of ephrin-B reverse signaling induces Dab-1 phosphorylation presumably via the recruitment and activation of Src family kinases by Ephrin-B membrane rafts [29]. Whereas biochemical evidence implicates ephrin-B reverse signaling in this process, whether the Src-dependent phosphorylation of B-type ephrins is required for this effect remains to be determined.

2.4. Other reverse signaling mechanisms

A mutation in which the entire cytoplasmic domain of ephrin-B2 was replaced with β-galactosidase in mice resulted in cardiac valve abnormalities and defects in urogenital-anorectal development, phenotypes not attributable to either ephrin-B2 phosphorylation or PDZ-dependent reverse signaling alone [30, 31]. Unlike deletions of the entire C-terminus, this fusion protein localizes to the plasma membrane, but inexplicably behaves dominantly with respect to urogenital abnormalities [22, 30]. The dominant nature of this phenotype is not due to haploinsuficiency, since efnB2+/− embryos did not display this phenotype. Instead, it has been proposed that beta-galactosidase driven multimerization may lead to abnormal forward signaling activation [22, 30]. The role for ephrin-B2 reverse signaling in cardiac valve development on the other hand may be due to collaborative function of PDZ- and phosphorylation-dependent reverse signaling. Although efnB25FΔV mutations have not yet been reported, no such combinatorial function was observed for efnB16FΔV mutant mice [5]. Other reverse signaling mechanisms may also exist. Interestingly, serine phosphorylation of ephrin-B2 is involved in the stabilization of AMPA receptors at the synapse by regulating PDZ-dependent reverse signaling, but genetic analysis of this mechanism has not yet been performed [32]. This and other molecular mechanisms (see section 4.2) may help to explain disparities between phenotypes caused by ephrin-B2 point mutations and cytoplasmic truncations.

3. Phosphoproteomics

Protein phosphorylation is a central component of all receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways. Over the past decade innovative mass-spectrometry based proteomic technologies supporting identification and quantification of protein phosphorylation have been advanced dramatically. These strategies generally employ chromatographic enrichment of phosphoproteins isolated from cell culture, often in conjunction with isotope labeling methods to allow quantitative analysis of downstream signaling networks by mass spectrometry (MS). Whereas tyrosine phosphorylation represents only approximately .05% of total protein phosphorylation it is currently the most tractable phosphorylation event for proteomic analysis owing to the existence of high-affinity, high-specificity anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies [33]. Such methods have been successful in identifying phosphorylation targets downstream of PDGFR, EGFR, FGFR, ErbB and recently Eph/ephrin signaling (reviewed in [33, 34]).

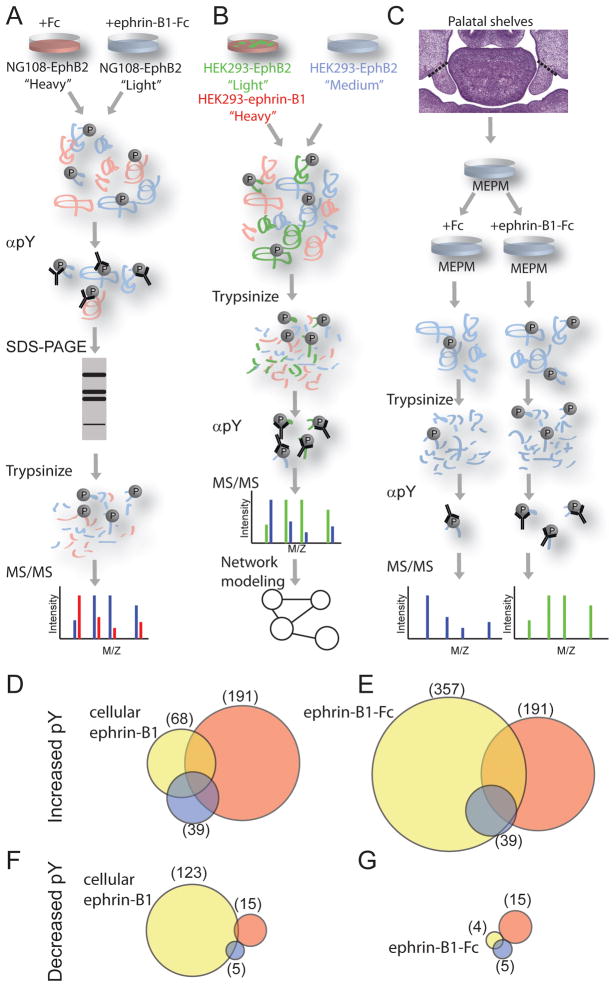

3.1. Eph/ephrin phosphoproteomics in neuronal cells

Initial applications of this technology to Eph/ephrin signaling utilized Stable Isotope Labeling by Amino acids in Cell culture (SILAC) to identify targets of ephrin-B1/EphB2 signaling in NG108 neuronal cells stably overexpressing EphB2 [35, 36]. In the SILAC method, protein from separate populations of cells is labeled by metabolic incorporation of either “heavy” or “light” isotope-containing amino acids allowing them to be distinguished and relatively quantified by MS (Fig. 1a). These labeled NG108 populations were treated either with pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc, or control treatment. Cell lysate from treated and untreated cells were combined, and an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody was used to immunoprecipitate proteins from combined cell lysates. Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and gel slices were then trypsinized and phosphoproteins were analyzed by MS. This same approach was applied utilizing two different MS technologies, quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometry (QTOF), and linear ion trap-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (LTQ-Orbitrap). Whereas the QTOF system identified 127 unique proteins, 46 of which showed a quantitative change in tyrosine phosphorylation, the LTQ-orbitrap system had higher sensitivity and increased accuracy of peptide quantitation and was able to quantify 777 proteins in two replicates, of which 204 showed at least a 1.5 fold change in phosphotyrosine abundance. Although a detailed comparison of the two technologies is beyond the scope of this review, it is worth noting that of the proteins identified by QTOF, concordance with LTQ-Orbitrap was relatively strong: of 127 proteins identified by QTOF, 95 were confirmed by LTQ-Orbitrap. These experiments provide an extensive resource for further analysis of downstream signaling pathways in a neuronal context.

Figure 1. Phospho-proteomic approaches to Eph/ephrin signaling networks.

(A–C) The workflow utilized in recent phosphoproteomic studies identifying targets of forward signaling. Each of these studies employed anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies to purify phosphorylated peptides. Key advantages to (A)[35, 36] and (B)[43], compared with (C)[45], involved the use of incorporation of SILAC labeling for quantitation; (B)[43] utilized cellular ephrin-B1 instead of ephrin-B1-Fc; and (C)[45] utilized primary cells with known developmental relevance. (D–G) Venn diagrams of overlap between phosphorylated protein targets of ephrin-B1 induced forward signaling identified by the three studies. Yellow (Jorgensen et al., 2009); (Zhang et al., 2006, 2008); Blue (Bush et al., 2009). (D, E) Proteins with increased tyrosine phosphorylation compared with cellular ephrin-B1 induction (Jorgensen et al., 2009) (D) or pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc induction (E). (F, G) Proteins with decreased tyrosine phosphorylation compared with cellular ephrin-B1 induction (yellow) (D) or pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc induction (yellow) (E). In all cases, blue and red were induced by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc.

3.2. Eph/ephrin phosphoproteomics in non-small cell lung cancer

Recently, phosphoproteomics methods were used to investigate the role of ephrin-B3 in non-small lung cancer (NSCLC)[37]. This study examined changes in the phosphoproteome between human NSCLC U-2810 cells in the presence or absence of ephrin-B3. SiRNA knockdown of ephrin-B3 causes decreased proliferation, and change cell shape indicating that ephrin-B3 expression has significance in these cells. Interestingly, this study did not utilize anti-phosphosphotyrosine antibodies, instead performing chromatographic enrichment with Strong Cation eXchange (SCX) followed by TiO2 chromatography (reviewed in [34]). These methods enrich for all phosphorylation events, enabling identification of serine and threonine in addition to tyrosine phosphorylation. Such approaches open the door to appreciating the importance of serine and threonine phosphorylation events in Eph/ephrin signaling networks.

3.3. Eph/ephrin phosphoproteomics in cell sorting

Eph/ephrin signaling influences cell sorting during hindbrain, limb, and craniofacial development, intestinal homeostasis, and peripheral nervous system regeneration [6, 38–42]. A systems biological approach integrating phosphoproteomics with functional, and protein-protein interaction data was utilized to analyze bidirectional signaling networks underlying Eph/ephrin mediated cell sorting (Fig 1B) [43]. HEK293 cells were stably transfected with EphB2 or ephrin-B1 and SILAC was used to label each cell population with a different isotopic tag. A control culture expressing either EphB2 or ephrin-B1 was labeled with a third isotopic label, and was used for relative quantification. When ephrin-B1+ and EphB2+ cells were combined in cell culture, bidirectional signaling is activated, causing EphB2+ and ephrin-B1+ expressing cells to sort out from each other [44]. By comparing tyrosine phosphorylation between co-culture activated EphB2+ cells with control EphB2+ cells that had not been mixed with ephrin-B1+ cells, the authors were able to identify and quantify differential tyrosine phosphorylation targets of forward signaling. Similarly, to identify phosphorylation targets of reverse signaling, co-culture activated ephrin-B1+ cells were compared to ephrin-B1+ control cells. In this way, this study was able to identify 276 differentially-regulated tyrosine phosphorylation sites on 185 protein targets of forward signaling; and 353 differentially-regulated tyrosine phosphorylation sites on 166 protein targets of reverse signaling.

This phosphoproteomic data was then integrated with results from a parallel siRNA screen that identified 200 targets that influence Eph/ephrin-mediated cell sorting behavior. Of these, 37 exhibited differential phosphorylation in response to forward signaling, and 26 in response to reverse signaling. From the combined phosphorylation and siRNA analysis, the authors selected 32 proteins to generate flag-tagged baits for co-immunoprecipitation MS analyses. This approach identified 1221 protein interacting proteins, which were used in combination with phosphoproteomic and siRNA data as inputs for modeling a bidirectional signaling network. In addition to the wealth of data provided for further study, several important predictions were made by this extensive systems biological approach.

First, perhaps not unexpectedly, information processing between EphB2+ cells and ephrin-B1+ cells was asymmetric, such that forward and reverse signaling utilized distinct signal transduction mechanisms. Second, by comparing induction with exogenous pre-clustered soluble EphB2-Fc or ephrinB1-Fc with induction by mixing cells expressing ephB2 or ephrin-B1, this study observed differences in the signaling network. Third, this study compared the phosphotyrosine network activated by ephrin-B1/EphB2 forward signaling with forward signaling activated by C-terminally truncated ephrin-B1ΔC lacking the entire intracellular domain and found that the degree of EphB2 phosphorylation and downstream “signal flow” was processed differently in the absence of the ephrin-B1 intracellular domain. It has been previously demonstrated by two independent groups, that C-terminally truncated B-type ephrins are not efficiently localized to the plasma membrane, presumably resulting in reduced forward signaling [22, 30]. When examined in this study, however, the authors reported similar localization of ephrin-B1 and ephrin-B1ΔC to the membrane in their cell lines. One possible explanation of this apparent discrepancy is that these stable cell lines were selected based on quantitation of surface expression, not total expression, and the membrane localized ephrin-B1ΔC may therefore represent a significantly smaller proportion of total ephrin-B1ΔC in the cell. Regardless, the amount of ephrin-B1 extracellular domain was similar, and it is therefore clear from these results that the intracellular domain of ephrin-B1 is required for normal activation of forward signaling networks. The phosphorylation of EphB2, and downstream phosphotyrosine network was also different in cells activated by ephrin-B1ΔV (PDZ-binding deficient) when compared with those activated by ephrin-B1 or ephrin-B1ΔC. This result is surprising in light of genetic analysis of efnB1ΔV knock-in mutations in mice which displayed normal levels of EphB2 phosphorylation in whole head extracts, and did not display phenotypic consequences in the majority of the contexts examined indicating dispensability of PDZ- binding ability [5].

3.4. Eph/ephrin posphoproteomics in craniofacial development

The apparent incongruence in PDZ-binding requirement described above could reflect the importance of considering biological context when defining signaling networks. We recently took a context-driven phosphoproteomics approach, utilizing primary mouse embryonic palatal mesenchyme (MEPM) cells expressing endogenous levels of EphB receptors to identify phosphorylation targets relevant to the role of ephrin-B1 in craniofacial development (Fig. 1C) [45]. Ephrin-B1 is highly expressed in the mesenchyme of the anterior secondary palatal shelves and is required for outgrowth of this embryonic structure. Interestingly, we found that EphB3 receptor was upregulated in ephrin-B1 mutant cells, and this upregulation was posttranscriptional in nature. Our phosphoproteomics study did not utilize isotope labeling, but was able to reliably identify 96 tyrosine phosphorylated proteins, 46 of which were qualitatively differentially phosphorylated in response to activation of ephrin-B1 signaling. By applying gene ontology (GO) analysis to this phosphoproteomic data, we identified key cell biological functions regulated by ephrin-B1 in the palate. Amongst these, we found that proteins involved in endocytosis and vesicle-mediated transport were significantly regulated targets. This caused us to re-examine the posttranscriptional regulation of EphB3 in light of endocytosis and receptor trafficking, allowing us to document in-situ regulation of an Eph receptor by endocytosis. This finding indicates that regulation of Eph receptor levels by endocytosis, previously only observed in cell culture systems, is also at play in vivo and may be an important component of Eph receptor regulation. Amongst these regulators of internalization were Rin1 and Stam2, two proteins that were known to cooperate to regulate EgfR internalization and degradation [46]. Interestingly a more recent study has shown that Rin1 also regulates endocytosis of EphA4 in Hela cells [47]. Our identification of phosphorylation of these proteins downstream of ephrin-B1 activation indicates that this pathway may be utilized more broadly to regulate endocytosis and degradation. Importantly, our results also suggest that observing Eph protein levels by immuno-staining may not be a reliable way to detect active sites of Eph/ephrin signaling. In fact, areas with apparently low levels of Eph receptor protein may often be areas in which high levels of signaling is occurring, and therefore rapid activation and degradation of Eph receptor.

3.5. Comparison across studies

We identified phosphorylation targets in a context with known in-vivo significance, making them likely to be relevant to this developmental process. To determine the extent to which core signal transduction components are likely to be different in different biological contexts and across organisms, we decided to re-visit the targets of ephrin-B1-activated forward signaling between multiple studies. We were able to map most IDs across organisms, enabling us to evaluate the overlap in proteins identified to be increased or decreased in phosphorylation between studies. For simplicity, we combined the two studies performed in NG108 cells induced by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc from Zhang et al.[35, 36]; comparing them to datasets in MEPMs induced by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc [45]; and HEK293 cells induced either by cells expressing ephrin-B1(Fig. 1D,F) or by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc (Fig. 1E,G) [43];. We found considerable overlap between these studies, with 11 proteins shared amongst MEPMs, NG108s, and HEK293 cells induced by cellular ephrin-B1 (Fig A). This comparison reveals that there is a significantly conserved set of phosphorylation targets of Eph/ephrin signaling across cell-types and even across organisms.

The overlap between MEPMs (which were induced with pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc) and HEK293 cells induced with pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc, was dramatically improved in comparison to HEK293 cells induced with cellular ephrin-B1(24 proteins compared with 15), supporting the observation that ephrin-B1-Fc induction produced different results [43]. It is possible that signaling by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc is truly qualitatively different from signaling induced by cellular ephrin-B1. Alternatively, this difference may be due to the fact that cellular ephrin-B1 would induce signaling only at interfaces between EphB2 and ephrin-B1-expressing cells, rather than in all cells as is the case for ephrin-B1-Fc inductions. Both the number of proteins and degree of differential phosphorylation in HEK293 cells by induction with pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc was dramatically increased compared with induction by cellular ephrin-B1 which may provide support for this explanation [43].

Interestingly, a significantly reduced degree of overlap exists in proteins that are dephosphorylated in response to induction of forward signaling. The higher concordance amongst proteins with increased, compared to those with decreased tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1C, D), may reflect that many of those increased tyrosine phosphorylation events are direct targets of EphB2 kinase activity, whereas those decreased in phosphorylation must be indirect events that involve activation of a phosphatase. Direct targets may therefore be more highly conserved than indirect ones across cell types and organisms.

4. Transcriptional regulation downstream of Eph/ephrin signaling

4.1. Transcriptional regulation by forward signaling

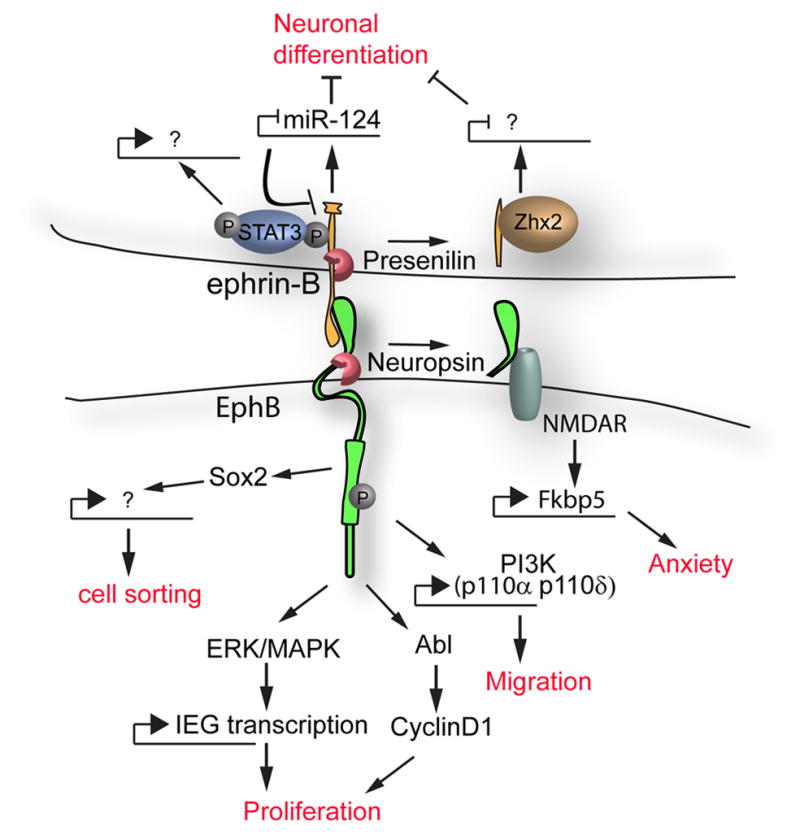

It is well recognized that Eph/ephrin signaling converges on regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in many contexts, but the downstream regulation of transcription by Eph/ephrin signaling has only recently begun to be appreciated. Recent studies indicate that Eph/ephrin mediated cell-sorting and regulation of cell proliferation both may involve transcriptional regulation. For example, the ability of peripheral nervous system (PNS) axons to regrow upon transection injury depends on EphB/ephrin-B-mediated sorting of Schwann cells and fibroblasts at the injury site [41]. Cell sorting results in discrete clusters of Schwann cells and fibroblasts both in vivo and in cell culture, and treatment with soluble pre-clustered ephrin-B2-Fc or cells expressing ephrin-B2 was able to induce cell sorting. Activation of EphB2 in Schwann cells results in relocalization of N-cadherin, a process that is dependent on expression of the transcription factor Sox2. Sox2 expression is required for Eph/ephrin mediated cell sorting, and Sox2 overexpression could rescue the effects of EphB2 knockdown on Schwann cell sorting, suggesting that Sox2 regulates transcription downstream of EphB2 to induce cell sorting. Indeed, the transcriptional inhibitor actinomycin D blocked the relocalization of N-cad supporting the importance of transcriptional regulation in this process. Finally, EphB2−/− loss of function resulted in impaired organization of axonal outgrowth during nerve regeneration, confirming the in-vivo relevance of this pathway.

One intriguing mechanism by which EphB2 can regulate transcription was recently identified in the context of anxiety control by the amygdala [48]. Stress causes a serine protease, Neuropsin, to cleave and release a 70kDa fragment of the EphB2 extracellular domain. It has been previously shown that EphB2 physically interacts with NMDA receptors at excitatory synapses, and activation of EphB2 by ephrin-B2 results in modulation of NMDAR-induced IEG expression changes [49, 50]. Stress reduced the association between EphB2 and NMDAR in wild-type but not neuropsin−/− mice indicating that cleavage by neuropsin is involved in regulating this interaction. A microarray approach comparing gene expression changes in the amygdala of neuropsin+/+ and neuropsin−/− mice identified 19 differentially-expressed genes, including increased expression of the co-chaperone FK506 binding protein 51 (Fkbp5), a gene that has also been implicated in development of anxiety. Upregulation of Fkbp5 and an anxious behavioral response to stress required neuropsin function and was abrogated by an EphB2 function-blocking antibody. Together these results introduce a model where stress-induced cleavage of EphB2 by neuropsin allows the extracellular domain of EphB2 to interact with NMDAR to converge on transcriptional regulation of Fkbp5 and development of anxiety.

4.2. Forward signaling transcriptomics

In the intestinal epithelium, EphB/ephrin-B signaling regulates both cell sorting and progenitor cell proliferation, and both of these processes are perturbed in intestinal adenomas with increased EphB expression [42, 51, 52]. To establish signaling pathways utilized to regulate proliferation and cell sorting in the intestinal epithelium, Genander et al. performed microarray analysis following acute inhibition of EphB forward signaling by intravenous injection of ephrin-B2-Fc [53]. Gene ontology analysis of the regulated genes indicated that two distinct transcriptional programs were altered when signaling was blocked: 1) cell/cycle regulation or progression and 2) cell localization and cytoskeletal regulation. These categories were further dissected by analyzing a series of mutations in the EphB2 receptor in mice. Disruption of the entire intracellular domain of EphB2 indicated that forward signaling was responsible for both proliferative and migratory functions [52]. Mice carrying an EphB2K661R/K661R point mutation abolishing EphB2 kinase activity exhibited disrupted cell proliferation, but not cell sorting, indicating that EphB2 forward signaling controlled these processes by separate kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Consistent with this hypothesis, mice carrying a constitutively active EphB2F620D/F620D mutation exhibited increased progenitor proliferation in intestinal crypts but not cell sorting defects [52]. Kinase-dependent regulation of cell proliferation depended on an Abl-cyclinD1 pathway, whereas kinase-independent controlled cell sorting through PI3K, possibly by controlling expression of the PI3K catalytic subunits p110α and p110δ [53].

We recently identified gene expression changes associated with the regulation of cell proliferation in the context of craniofacial development. Surprisingly, an immediate early gene (IEG) transcriptional response, a hallmark of other receptor tyrosine kinase signaling pathways, had not been reported for Eph/ephrin signaling. We therefore utilized MEPMs to examine whether an IEG response was characteristic of Eph/ephrin signaling in this context [45]. Induction of forward signaling by pre-clustered ephrin-B1-Fc resulted in the regulation of a surprisingly small set of IEG targets that strikingly implicated the ERK/MAPK signal transduction pathway in this process. The regulation of these IEGs was dynamic, and shadowed the kinetics of ERK/MAPK activation. Further, the regulation of this set of IEGs depended on activation of the ERK/MAPK pathway. Interestingly three of these targets were themselves negative feedback regulators of the ERK/MAPK pathway indicating the possibility of feedback regulation. Blocking the ERK/MAPK pathway also blocked the mitogenic effect of ephrin-B1 in palatal cells, indicating that this signal transduction pathway was critical to the regulation of cell proliferation downstream of Eph/ephrin signaling in craniofacial development.

4.2. Transcriptional regulation by reverse signaling

Ephrin-B reverse signaling has been implicated in transcriptional control, and several potential mechanisms have been identified. In Xenopus oocytes, the STAT3 transcription factor can bind to the intracellular domain of ephrin-B1 dependent on its phosphorylation, leading to Jak2-dependent phosphorylation of STAT3 and enhancement of transcriptional activity. It has been previously shown that the intracellular domain of B-type ephrins can be cleaved by presenilins; the cleaved intracellular domain of ephrin-B1 can translocate to the nucleus and enhance Zhx2 transcriptional activity to maintain neural progenitor state [54–56]. Activation of Ephrin-B1 reverse signaling negatively regulates the transcription of microRNA miR-124, both in neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and in the telencephalon [57]. As ephrin-B1 is itself a target of post-transcriptional regulation by miR-124, this regulation initiates a feedback loop that regulates expression of efnb1 to influence neuronal differentiation.

5. Conclusions

All methodologies used to study Eph/ephrin signaling support the view of this signaling family as a large and complex part of multiple overlapping signaling networks. Whereas symmetric phenotypic data for specific signaling mutations in receptor/ligand and receptor/effector pairs is the most compelling evidence in constructing signaling pathways, it does not have the power to build broad networks, or to uncover novel components of these networks. An approach integrating systems-based methodologies such as proteomics and transcriptomics, combined with carefully selected genetic manipulations provide a more complete picture of in vivo signal transduction mechanisms utilized. So far, few efforts have been made to integrate either proteomic or transcriptomic data with genetic manipulations of the signaling pathway. As methodologies advance, one could envision utilizing mice harboring signaling mutations to generate proteomic or transcriptomic data specific to a particular signaling mechanism. Conversely, the ability to identify specific tyrosine residues on target proteins exhibiting Eph/ephrin-regulated phosphorylation presents the opportunity to generate mouse models in which signaling through key phosphotyrosine sites can be analyzed. Fortunately, a wide array of outstanding cell biological tools and genetic and embryologic approaches from other organisms also provide a wealth of information to draw on. The integration of data from diverse sources, and reapplication to specific in vivo contexts is a key step in defining Eph/ephrin signaling mechanisms.

Figure 2. Transcriptional regulation by EphB/ephrin-B signaling.

Forward and reverse signaling through EphB/ephrin-B signaling can result in transcriptional regulation by a number of proposed mechanisms. Signaling pathways leading to transcriptional responses are connected by arrows; transcriptional activation or repression is indicated. The biological consequences of this regulation are indicated in red.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to many colleagues whose work we could not discuss due to space limitations. We are grateful to Nancy Ann Oberheim for helpful comments on the manuscript. J.O.B was supported by grant R00DE020855 from the NIH/NIDCR. P.S. was supported by grant R37HD25326 from the NIH/NICHD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Henkemeyer M, Orioli D, Henderson JT, Saxton TM, Roder J, Pawson T, et al. Nuk controls pathfinding of commissural axons in the mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1996;86:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80075-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Orioli D, Henkemeyer M, Lemke G, Klein R, Pawson T. Sek4 and Nuk receptors cooperate in guidance of commissural axons and in palate formation. Embo J. 1996;15:6035–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davy A, Soriano P. Ephrin signaling in vivo: look both ways. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:1–10. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risley M, Garrod D, Henkemeyer M, McLean W. EphB2 and EphB3 forward signalling are required for palate development. Mech Dev. 2009;126:230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bush JO, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 regulates axon guidance by reverse signaling through a PDZ-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1586–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.1807209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Compagni A, Logan M, Klein R, Adams RH. Control of skeletal patterning by ephrinB1-EphB interactions. Dev Cell. 2003;5:217–30. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00198-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davy A, Aubin J, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 forward and reverse signaling are required during mouse development. Genes Dev. 2004;18:572–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.1171704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dottori M, Hartley L, Galea M, Paxinos G, Polizzotto M, Kilpatrick T, et al. EphA4 (Sek1) receptor tyrosine kinase is required for the development of the corticospinal tract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13248–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.22.13248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kullander K, Butt SJ, Lebret JM, Lundfald L, Restrepo CE, Rydstrom A, et al. Role of EphA4 and EphrinB3 in local neuronal circuits that control walking. Science. 2003;299:1889–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1079641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kullander K, Croll SD, Zimmer M, Pan L, McClain J, Hughes V, et al. Ephrin-B3 is the midline barrier that prevents corticospinal tract axons from recrossing, allowing for unilateral motor control. Genes Dev. 2001;15:877–88. doi: 10.1101/gad.868901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kullander K, Mather NK, Diella F, Dottori M, Boyd AW, Klein R. Kinase-dependent and kinase-independent functions of EphA4 receptors in major axon tract formation in vivo. Neuron. 2001;29:73–84. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00181-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokoyama N, Romero MI, Cowan CA, Galvan P, Helmbacher F, Charnay P, et al. Forward signaling mediated by ephrin-B3 prevents contralateral corticospinal axons from recrossing the spinal cord midline. Neuron. 2001;29:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egea J, Nissen UV, Dufour A, Sahin M, Greer P, Kullander K, et al. Regulation of EphA 4 kinase activity is required for a subset of axon guidance decisions suggesting a key role for receptor clustering in Eph function. Neuron. 2005;47:515–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beg AA, Sommer JE, Martin JH, Scheiffele P. alpha2-Chimaerin is an essential EphA4 effector in the assembly of neuronal locomotor circuits. Neuron. 2007;55:768–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegmeyer H, Egea J, Rabe N, Gezelius H, Filosa A, Enjin A, et al. EphA4-dependent axon guidance is mediated by the RacGAP alpha2-chimaerin. Neuron. 2007;55:756–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi L, Fu WY, Hung KW, Porchetta C, Hall C, Fu AK, et al. Alpha2-chimaerin interacts with EphA4 and regulates EphA4-dependent growth cone collapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16347–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706626104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fawcett JP, Georgiou J, Ruston J, Bladt F, Sherman A, Warner N, et al. Nck adaptor proteins control the organization of neuronal circuits important for walking. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20973–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710316105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. Ephrins in reverse, park and drive. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:339–46. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendes SW, Henkemeyer M, Liebl DJ. Multiple Eph receptors and B-class ephrins regulate midline crossing of corpus callosum fibers in the developing mouse forebrain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:882–92. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3162-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerety SS, Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Symmetrical mutant phenotypes of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:403–14. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–53. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makinen T, Adams RH, Bailey J, Lu Q, Ziemiecki A, Alitalo K, et al. PDZ interaction site in ephrinB2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 2005;19:397–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.330105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawamiphak S, Seidel S, Essmann CL, Wilkinson GA, Pitulescu ME, Acker T, et al. Ephrin-B2 regulates VEGFR2 function in developmental and tumour angiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:487–91. doi: 10.1038/nature08995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Nakayama M, Pitulescu ME, Schmidt TS, Bochenek ML, Sakakibara A, et al. Ephrin-B2 controls VEGF-induced angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature. 2010;465:483–6. doi: 10.1038/nature09002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davy A, Soriano P. Ephrin-B2 forward signaling regulates somite patterning and neural crest cell development. Dev Biol. 2007;304:182–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouzioukh F, Wilkinson GA, Adelmann G, Frotscher M, Stein V, Klein R. Tyrosine phosphorylation sites in ephrinB2 are required for hippocampal long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. J Neurosci. 2007;27:11279–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3393-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu NJ, Henkemeyer M. Ephrin-B3 reverse signaling through Grb4 and cytoskeletal regulators mediates axon pruning. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:268–76. doi: 10.1038/nn.2254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Senturk A, Pfennig S, Weiss A, Burk K, Acker-Palmer A. Ephrin Bs are essential components of the Reelin pathway to regulate neuronal migration. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer A, Zimmer M, Erdmann KS, Eulenburg V, Porthin A, Heumann R, et al. EphrinB phosphorylation and reverse signaling: regulation by Src kinases and PTP-BL phosphatase. Mol Cell. 2002;9:725–37. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cowan CA, Yokoyama N, Saxena A, Chumley MJ, Silvany RE, Baker LA, et al. Ephrin-B2 reverse signaling is required for axon pathfinding and cardiac valve formation but not early vascular development. Dev Biol. 2004;271:263–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dravis C, Yokoyama N, Chumley MJ, Cowan CA, Silvany RE, Shay J, et al. Bidirectional signaling mediated by ephrin-B2 and EphB2 controls urorectal development. Dev Biol. 2004;271:272–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Essmann CL, Martinez E, Geiger JC, Zimmer M, Traut MH, Stein V, et al. Serine phosphorylation of ephrinB2 regulates trafficking of synaptic AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1035–43. doi: 10.1038/nn.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nita-Lazar A, Saito-Benz H, White FM. Quantitative phosphoproteomics by mass spectrometry: past, present, and future. Proteomics. 2008;8:4433–43. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macek B, Mann M, Olsen JV. Global and site-specific quantitative phosphoproteomics: principles and applications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:199–221. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang G, Fenyo D, Neubert TA. Screening for EphB signaling effectors using SILAC with a linear ion trap-orbitrap mass spectrometer. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:4715–26. doi: 10.1021/pr800255a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang G, Spellman DS, Skolnik EY, Neubert TA. Quantitative phosphotyrosine proteomics of EphB2 signaling by stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) J Proteome Res. 2006;5:581–8. doi: 10.1021/pr050362b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stahl S, Mm Branca R, Efazat G, Ruzzene M, Zhivotovsky B, Lewensohn R, et al. Phosphoproteomic Profiling of NSCLC Cells Reveals that Ephrin B3 Regulates Pro-survival Signaling through Akt1-Mediated Phosphorylation of the EphA2 Receptor. J Proteome Res. 2011 doi: 10.1021/pr200037u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooke J, Moens C, Roth L, Durbin L, Shiomi K, Brennan C, et al. Eph signalling functions downstream of Val to regulate cell sorting and boundary formation in the caudal hindbrain. Development. 2001;128:571–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davy A, Bush JO, Soriano P. Inhibition of gap junction communication at ectopic Eph/ephrin boundaries underlies craniofrontonasal syndrome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu Q, Mellitzer G, Robinson V, Wilkinson DG. In vivo cell sorting in complementary segmental domains mediated by Eph receptors and ephrins. Nature. 1999;399:267–71. doi: 10.1038/20452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parrinello S, Napoli I, Ribeiro S, Digby PW, Fedorova M, Parkinson DB, et al. EphB signaling directs peripheral nerve regeneration through Sox2-dependent Schwann cell sorting. Cell. 2010;143:145–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cortina C, Palomo-Ponce S, Iglesias M, Fernandez-Masip JL, Vivancos A, Whissell G, et al. EphB-ephrin-B interactions suppress colorectal cancer progression by compartmentalizing tumor cells. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1376–83. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jorgensen C, Sherman A, Chen GI, Pasculescu A, Poliakov A, Hsiung M, et al. Cell-specific information processing in segregating populations of Eph receptor ephrin-expressing cells. Science. 2009;326:1502–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1176615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poliakov A, Cotrina ML, Pasini A, Wilkinson DG. Regulation of EphB2 activation and cell repulsion by feedback control of the MAPK pathway. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:933–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bush JO, Soriano P. Ephrin-B1 forward signaling regulates craniofacial morphogenesis by controlling cell proliferation across Eph-ephrin boundaries. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2068–80. doi: 10.1101/gad.1963210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kong C, Su X, Chen PI, Stahl PD. Rin1 interacts with signal-transducing adaptor molecule (STAM) and mediates epidermal growth factor receptor trafficking and degradation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15294–301. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611538200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deininger K, Eder M, Kramer ER, Zieglgansberger W, Dodt HU, Dornmair K, et al. The Rab5 guanylate exchange factor Rin1 regulates endocytosis of the EphA4 receptor in mature excitatory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12539–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801174105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Attwood BK, Bourgognon JM, Patel S, Mucha M, Schiavon E, Skrzypiec AE, et al. Neuropsin cleaves EphB2 in the amygdala to control anxiety. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dalva MB, Takasu MA, Lin MZ, Shamah SM, Hu L, Gale NW, et al. EphB receptors interact with NMDA receptors and regulate excitatory synapse formation. Cell. 2000;103:945–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takasu MA, Dalva MB, Zigmond RE, Greenberg ME. Modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent calcium influx and gene expression through EphB receptors. Science. 2002;295:491–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1065983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Batlle E, Henderson JT, Beghtel H, van den Born MM, Sancho E, Huls G, et al. Beta-catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the intestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of EphB/ephrinB. Cell. 2002;111:251–63. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmberg J, Genander M, Halford MM, Anneren C, Sondell M, Chumley MJ, et al. EphB receptors coordinate migration and proliferation in the intestinal stem cell niche. Cell. 2006;125:1151–63. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Genander M, Halford MM, Xu NJ, Eriksson M, Yu Z, Qiu Z, et al. Dissociation of EphB2 signaling pathways mediating progenitor cell proliferation and tumor suppression. Cell. 2009;139:679–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Georgakopoulos A, Litterst C, Ghersi E, Baki L, Xu C, Serban G, et al. Metalloproteinase/Presenilin1 processing of ephrinB regulates EphB-induced Src phosphorylation and signaling. Embo J. 2006;25:1242–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tomita T, Tanaka S, Morohashi Y, Iwatsubo T. Presenilin-dependent intramembrane cleavage of ephrin-B1. Mol Neurodegener. 2006;1:2. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu C, Qiu R, Wang J, Zhang H, Murai K, Lu Q. ZHX2 Interacts with Ephrin-B and regulates neural progenitor maintenance in the developing cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29:7404–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5841-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arvanitis DN, Jungas T, Behar A, Davy A. Ephrin-B1 reverse signaling controls a posttranscriptional feedback mechanism via miR-124. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2508–17. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01620-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, Deutsch U, et al. Roles of ephrinB ligands and EphB receptors in cardiovascular development: demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis, and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grunwald IC, Korte M, Adelmann G, Plueck A, Kullander K, Adams RH, et al. Hippocampal plasticity requires postsynaptic ephrinBs. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:33–40. doi: 10.1038/nn1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grunwald IC, Korte M, Wolfer D, Wilkinson GA, Unsicker K, Lipp HP, et al. Kinase-independent requirement of EphB2 receptors in hippocampal synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2001;32:1027–40. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wilkinson GA, Schittny JC, Reinhardt DP, Klein R. Role for ephrinB2 in postnatal lung alveolar development and elastic matrix integrity. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:2220–34. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsieh CY, Nakamura PA, Luk SO, Miko IJ, Henkemeyer M, Cramer KS. Ephrin-B reverse signaling is required for formation of strictly contralateral auditory brainstem pathways. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9840–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0386-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]