Abstract

We tested the hypothesis that meiotic competence of dog oocytes was tightly linked with donor follicle size and energy metabolism. Oocytes were recovered from small (< 1 mm diameter, n = 327), medium (1 – < 2 mm, n = 292) or large (≥ 2 mm, n = 102) follicles, cultured for 0, 24 or 48 h, assessed for glycolysis, glucose oxidation, pyruvate uptake, glutamine oxidation and then nuclear status. More oocytes (P < 0.05) from large follicles (37%) reached the metaphase II (MII) stage than from the small group (11%), with the medium size class being intermediate (18%; P > 0.05). Glycolytic rate increased (P < 0.05) as oocytes progressed from the germinal vesicle (GV) to MII stage. At 48 h of culture, oocytes completing nuclear maturation had higher (P < 0.05) glycolytic rate than those arrested at earlier stages. GV oocytes recovered from large follicle oocytes had higher (P < 0.05) metabolism than those from smaller counterparts at culture onset. MII oocytes from large follicles oxidized more (P < 0.05) glutamine than the same stage gametes recovered from smaller counterparts. In summary, larger size dog follicles contain a more metabolically-active oocyte with a greater chance of achieving nuclear maturation in vitro. These findings demonstrate a significant role of energy metabolism in promoting dog oocyte maturation, information that will be useful for improving culture systems for rescuing intraovarian genetic material.

Keywords: dog oocyte, metabolism, follicle size, meiotic competence, glycolysis, glutamine oxidation

Introduction

The fundamental reproductive physiology of the dog, especially associated with the oocyte, is unique compared to other species (Songsasen and Wildt 2007). In most mammals, ovulation occurs after oocytes have reached MII in the preovulatory follicle. Such in vivo maturation requires about 10 to 13 h in the mouse (Edwards and Gates 1959) and 16 to 24 h in the cow (Dominko and First 1997). By contrast, the ovulating dog follicle releases an immature oocyte that is incapable of fertilization (Phemister et al. 1973). Rather, oocyte maturation occurs in the oviduct over the course of the next 48 to 72 h post-ovulation and when circulating progesterone is elevated (Concannon et al. 1989; Reynaud et al. 2005; Tsutsui 1989; Wildt et al., 1979).

This distinctiveness in female gamete function is believed to contribute to the complexities experienced in culturing dog oocytes in vitro (i.e., in vitro maturation; IVM) (Songsasen and Wildt 2007). Stimulating dog oocytes to complete nuclear maturation in vitro has been especially challenging. It is common for 60 to 80% of healthy-appearing, germinal vesicle (GV) stage domestic cat (Godard et al. 2009), mouse (Marín Bivens et al. 2004), goat (Khatun et al. 2011), sheep (Shirazi et al. 2010), pig (Koike et al. 2010) and cow (Sirard et al. 1988) oocytes to transition from germinal vesicle (GV) stage to MII in vitro. Under these same laboratory conditions, and with studies conducted by multiple, independent laboratories, only 20% of dog oocytes generally reach the MII stage (Alhaider and Watson 2009; Bolamba et al. 1998; Evecen et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2004; Luvoni et al. 2001; Mahi and Yanagimachi 1976; Nickson et al. 1993; Otoi et al. 2000; Rodrigues et al. 2009; Silva et al. 2010, Saint-Dizier et al. 2001; Shimazu et al. 1992; Songsasen and Wildt 2007; Yamada et al. 1993). One factor identified as having a major influence on IVM success of the dog oocyte is the dimension of the donor follicle (Songsasen and Wildt 2005). Larger size follicles provide oocytes with higher meiotic competency. For example, nearly 80% of oocytes recovered from follicles > 2 mm in diameter have the capacity to achieve MII compared to 38% from 1 to 2 mm, 26% from > 0.5 to 1 mm and 17% from < 0.5 mm follicles (Songsasen and Wildt 2005). However, these larger size follicles are rare, occurring almost exclusively during proestrus and estrus (each about 1 wk in duration and occurring only once or twice annually). Otherwise, the bitch is usually experiencing diestrus (active luteal function) and anestrus (ovarian quiescence) for combined intervals of 5 to 10 mo when the gonads contain mostly pre- and early antral follicles of ≤ 1 mm in diameter. Thus, during its reproductive lifespan, the female dog is not continuously cyclic like most species, but rather has ovaries mostly comprised of small diameter follicles containing meiotically-incompetent oocytes, thereby explaining the consistently poor IVM success for the species.

It is well established that energy metabolism, especially glucose is a prerequisite for maturation of mammalian oocytes, primarily because of the need for ATP for development (Krisher et al. 2007; Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010). Specifically, oocytes have been found to metabolize glucose through glycolysis and the pentose-phosphate- (PPP), hexoxamine- and polyol pathways (Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010), with the first two known to affect nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of mouse (Downs 1995), pig (Herrick et al. 2006; Krisher et al. 2007), cow (Rieger and Loskutoff 1994; Steeves and Gardner 1999) and cat (Spindler et al. 2000) oocytes. Utilization of glucose through glycolysis produces energy (ATP) and pyruvate, the substrate of the downstream tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA). Glycolytic rate has been useful for predicting the effectiveness of a given set of in vitro culture conditions as well as predicting the likely developmental competence of cow (Krisher and Bavister 1999) and cat (Spindler et al. 2000) oocytes. For the latter species (another carnivore like the dog), glucose metabolism increases as immature cat oocytes progress through meiotic maturation from the GV to MII stage (Spindler et al. 2000). These same investigators also have demonstrated that developmental competence post-fertilization, including the ability to advance to the blastocyst stage, directly depends on glycolytic rate. Although not producing ATP, the PPP generates NADPH that is essential for cytoplasmic integrity and glutathione production (Garcia et al. 2010; Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010). Furthermore, PPP produces ribose-5-phosphate that is critical for DNA and RNA syntheses (Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010).

Previous research in our laboratory indicates that pyruvate uptake and glutamine oxidation are inherently linked to meiotic stages of the dog oocyte (Songsasen et al. 2007). Thus far, there is no information on metabolic patterns of dog oocytes recovered from various follicular sizes. For this study, we hypothesized that: 1) there are variations in metabolic activity of dog oocytes recovered from differing size follicles; and 2) oocyte metabolism is tightly associated with this cell’s ability to achieve nuclear maturation in vitro. Our specific objectives were to determine glycolysis, glucose oxidation, pyruvate uptake and glutamine oxidation of dog oocytes obtained from various follicle sizes and at different stages of meiotic development.

Results

At 0 h of IVM, most oocytes (>80%) recovered from large follicles were at the GV stage, whereas ~40% from small and medium counterparts had resumed meiosis based on undergoing germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) or achieving MI (Table 1). At 24 h of culture, the preponderance of oocytes in all follicle classes (42 – 47%) was at the GVBD stage and did not differ (P > 0.05) among follicle size groups. However, at 48 h of incubation, more oocytes (P < 0.05) from large follicles completed nuclear maturation (37% MII) compared to those from smaller counterparts (~12 – 18%). Furthermore, ~65% of oocytes from large follicles reached a combined MI/MII stage compared to only ~33% and 47% from small and medium follicles, respectively (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Meiotic status (% mean ± SEM) of oocytes recovered from small, medium or large follicles after 0 (n = 147), 24 (n = 240) or 48 h (n = 311) in vitro maturation.

| Culture times (h) | Meiotic stage | Follicle groups

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small (< 1 mm) | Medium (1 to < 2 mm) | Large (> 2 mm) | ||

| 0 | GV | 57.1 ± 10.7 | 58.4 ± 9.5 | 83.3 ± 16.7 |

| GVBD | 35.7 ± 9.5 | 37.3 ± 9.2 | 16.7 ± 16.7 | |

| MI | 4.9 ± 3.5 | 4.4 ± 2.5 | 0.0 | |

|

| ||||

| 24 | Degenerate | 15.1 ± 4.3a,b | 7.9 ± 3.3a,b | 1.6a |

| GV | 32.4 ± 7.4b | 33.2 ± 8.0b,c | 18.7 ± 9.1a,b | |

| GVBD | 42.2 ± 6.2b | 46.1 ± 7.4c | 46.9 ± 8.7b | |

| MI | 9.3 ± 3.9a,b | 12.8 ± 3.5a,b | 29.7 ± 8.6a,b | |

| MII | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| PN | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 ± 3.1 | |

|

| ||||

| 48 | Degenerate | 22.1 ± 5.3 | 12.9 ± 3.6 | 17.8 ± 7.6a,b |

| GV | 26.5 ± 6.3 | 20.3 ± 5.3 | 5.9 ± 4.1a | |

| GVBD | 18.4 ± 4.4 | 20.6 ± 5.2 | 6.6 ± 4.7a | |

| MI | 21.2 ± 4.7 | 29.4 ± 6.5 | 27.2 ± 8.2a,b | |

| MII | 11.7 ± 4.8* | 17.7 ± 5.2*,# | 37.4 ± 11.0b,# | |

| PN | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 ± 3.3a | |

Different letters indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences among nuclear stages within the same follicle group and culture period.

Different symbols indicate significant difference among follicle groups within the same meiotic stage and culture interval. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II; PN, parthenote.

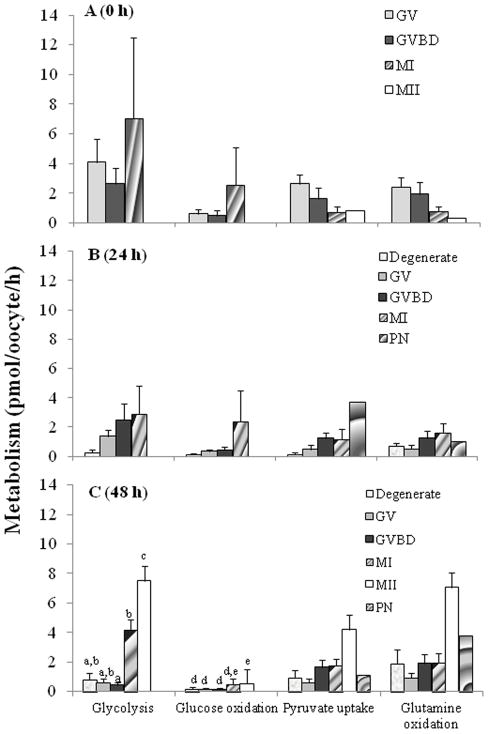

When oocytes of different developmental stages were compared, there were no differences (P > 0.05) in metabolic activities at 0 (Fig. 1A) or 24 (Fig. 1B) h of culture. However, metabolism was significantly affected by 48 h when we observed higher (P < 0.05) levels of glycolysis and glucose oxidation in MII compared to degenerate, GV and GVBD oocytes (Fig. 1C). Although glycolytic rate was higher (P < 0.05) in MII compared to MI counterparts at this time, glucose oxidation was comparable (P > 0.05) between these two meiotic stages (Fig. 1C). Degenerate oocytes had low metabolic activity throughout the incubation interval (Figs. 1A to C).

Fig. 1.

Glycolysis, glucose oxidation, pyruvate uptake and glutamine oxidation rates of dog oocytes assessed at (A) 0 h (n = 147), (B) 24 h (n = 240) and (C) 48 h (n = 311) of culture. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II; PN, parthenote. abcdeIndicates differences (P < 0.05) in metabolism among meiotic stages.

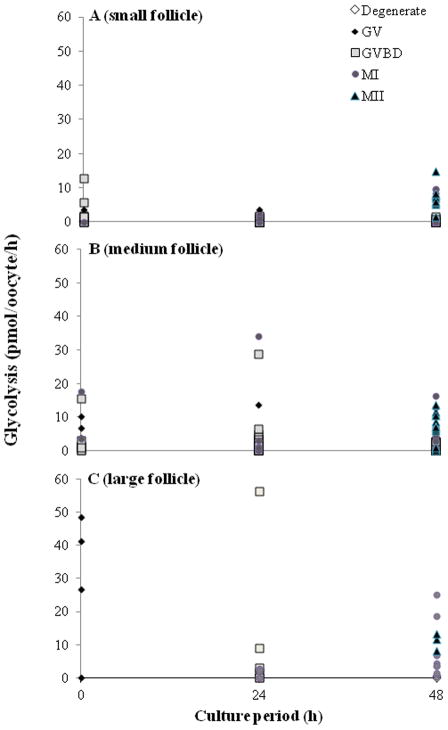

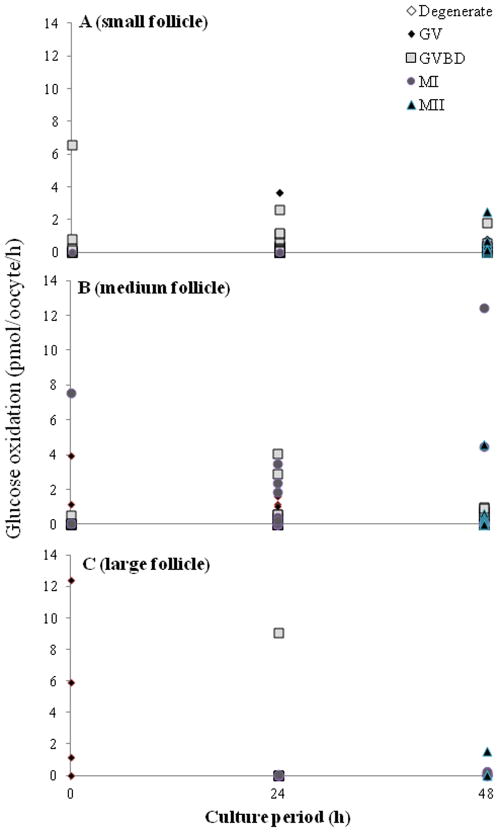

Follicle size influenced oocyte metabolism. Specifically, GV oocytes from large follicles were undergoing ~5 to 10 fold higher (P < 0.05) glycolysis (Fig. 2; at 0 [29.1 ± 10.7 vs. 0.4 ± 0.3 and 2.2 ± 0.8]) and 10 to 20 fold higher glucose oxidation (Fig. 3; at 0 h) (average, 4.9 ± 2.8 pmol/oocyte/h ) compared to small (0.0 ± 0.0) and medium (0.2 ± 0.2) size follicle groups. A higher (P < 0.05) glycolytic rate was sustained for MII (8.2 ± 1.6; 13.0 ± 1.7 pmol/oocyte/h) versus MI (4.4 ± 1.7; 9.5 ± 3.7 pmol/oocyte/h) stage oocytes at 48 h for medium and large follicle classes, respectively. By contrast glucose oxidation remained constant throughout incubation and regardless of meiotic development (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Glycolytic rates in oocytes recovered from (A) small (n = 150), (B) medium (n = 146) or (C) large follicles (n =29) cultured for 0, 24 or 48 h. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II.

Fig. 3.

Glucose oxidation rates in oocytes recovered from (A) small (n = 150), (B) medium (n =146) or (C) large follicles (n = 29) cultured for 0, 24 or 48 h. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II.

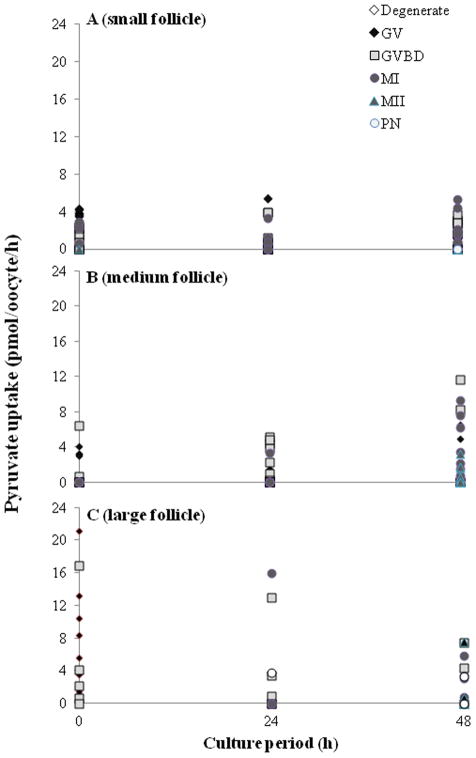

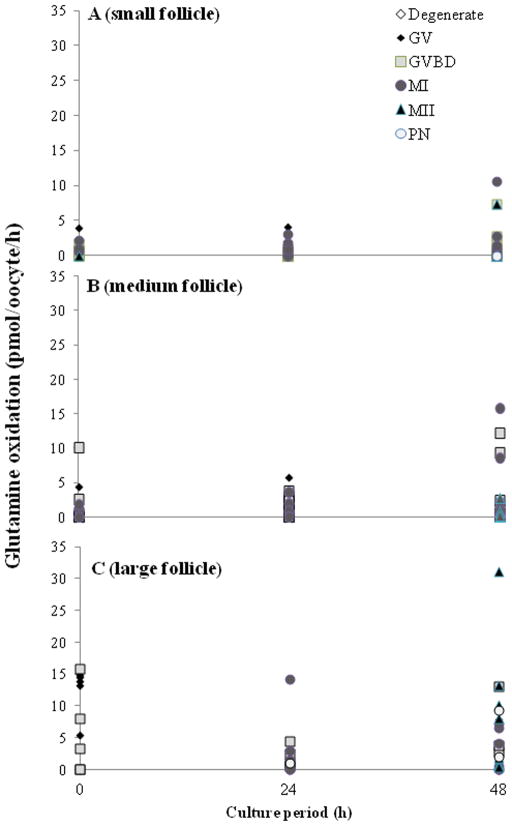

At the onset of in vitro culture, GV oocytes from the largest follicles had the highest (P < 0.05) pyruvate uptake (7.2 ± 2.3 pmole/oocyte/h; Fig. 4) and glutamine (9.0 ± 2.2; Fig. 5) metabolism compared to the two other follicle classes (average for pyruvate, small: 1.8 ± 0.4 and medium: 1.1 ± 0.4; for glutamine, small: 0.7 ± 0.2 and medium: 0.9 ± 0.3). However, pyruvate metabolism did not vary (P > 0.05) over the course of any given culture period either among meiotic statuses or follicular classes. In contrast, MI oocytes from small follicles had a higher (P < 0.05) rate of glutamine oxidation at 24 h of incubation (0.8 ± 0.3 pmol/oocyte/ h) than those at the GV (0.2 ± 0.2) and GVBD (0.1 ± 0.1) stages (Fig. 5). Similarly, glutamine oxidation was higher (P < 0.05) in MI oocytes from medium follicle than that of the GV stage (0.8 ± 0.3 vs. 0.2 ± 0.2 pmol/oocyte/h). No such differences (P > 0.05) were revealed in those stage oocytes recovered from large follicles, perhaps due to small sample size. However, MII oocytes from large follicles had a ~2 to 3-fold higher (P < 0.05) glutamine oxidation rate (19.8 ± 12.4 pmol/oocyte/h) by 48 h of incubation compared to small (1.2 ± 1.2) and medium (0.35 ± 0.3) counterparts.

Fig. 4.

Pyruvate uptake rates in oocytes recovered from (A) small (n = 177), (B) medium (n = 145) or (C) large follicles (n = 51) cultured for 0, 24 or 48 h. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II; PN, parthenote.

Fig. 5.

Glutamine oxidation rates in oocytes recovered from (A) small (n = 177), (B) medium (n = 145) or (C) large follicles (n = 51) cultured for 0, 24 or 48 h. GV, germinal vesicle; GVBD, germinal vesicle breakdown; MI, metaphase I; MII, metaphase II; PN, parthenote.

When metabolism of oocytes at the expected stage for each culture interval (i.e., GV at 0 h; GVBD and MI at 24 h; MII at 48 h) were compared, it was determined that MII oocytes from small and medium follicles had a higher (P < 0.05) glycolytic rate (7.2 ± 1.1 and 8.2 ± 1.6 pmol/oocyte/h, respectively) than those at the GV stage (0.4 ± 0.3 and 2.2 ± 0.8, respectively). By contrast, values for GVBD oocytes from small (0.3 ± 0.1) and medium (2.9 ± 1.3) follicles and for MI gametes from small (1.0 ± 0.6) and medium (4.5 ± 3.7) classes were intermediate and no different (P > 0.05). There were no differences (P > 0.05) in glycolysis among meiotic stages in large follicle group. There were no changes (P > 0.05) in glucose oxidation, pyruvate uptake or glutamine oxidation as oocytes progressed through GV to GVBD to MI to MII stages.

Discussion

Metabolic pattern studies are known to be key for generating fundamental information useful to enhancing the culture of oocytes in vitro (Rieger and Loskutoff 1994; Krisher et al. 2007). To improve such knowledge for the understudied dog oocyte, we conducted a multi-evaluation of substrate use. We discovered four important features. First, not only did oocytes from large follicles have a higher capacity to achieve nuclear maturation after in vitro culture, they also had higher rates of certain types of energy metabolism compared to those from smaller counterparts. For example, MII oocytes from follicles > 2 mm diameter oxidized glutamine at a far greater rate than the same stage oocytes from smaller follicles. Secondly, oocytes completing nuclear maturation (i.e., reaching the MII stage) by 48 h of culture had higher glucose metabolism than those of earlier stages. Clearly, metabolic function was an excellent indicator of dog oocyte maturational capacity, as has been observed in the cow (Krisher and Bavister 1999), mouse (Preis et al 2005) and cat (Spinder et al 2000). Thirdly, we demonstrated that certain expressions of energy metabolism depended on type of dog oocyte (i.e., stage of developmental competence regardless of follicle source). Specifically, MII oocytes had a higher rate of glycolysis than those at the GV or GVBD stage, suggesting that this metabolic pathway was involved in final nuclear maturation. Finally, overall data re-emphasized the uniqueness of this model in that the dog oocyte metabolized glucose through glycolysis at a much higher rate than previously reported for other species (Downs and Utecht 1999; Spindler et al. 2000; Steeves and Gardner 1999).

It is well established that oocyte developmental competence is acquired during the growth phase of folliculogenesis/oogenesis, and that this capacity is correlated to ovarian follicle size, including in the dog (Songsasen and Wildt 2005). Consistent with what we found in the latter investigation, our present study confirmed that achieving MII success in this species was closely linked to donor follicle size. Maturational success for oocytes recovered from large follicles was two- and three-fold higher than for those recovered from medium and small counterparts, respectively. It also was noteworthy that the MII rate (37%) in the present study was much more subdued than the 80% success achieved in our early report. We believe the difference between studies is due to the slight change in our definition of ‘large’ follicle in the present investigation to those that are 2 mm in diameter (rather than our earlier criterion of being > 2 mm in size). This was done as a logistical measure to increase the number of available large follicles. However, apparently even a modest change in what is considered a large dog follicle can alter subsequent nuclear maturation success. Interestingly, the present study also revealed that 40% of oocytes from small follicles already were at the GVBD stage before culture onset. Additionally, we noted some oocytes at MI at 0 h and others at MII/PN at 24 h of culture. Yamada et al. (1993) reported that a few dog oocytes from preovulatory and anestrual follicles can progress to MII within 24 h of being placed in culture. But we suspect that our observations of early GVBD and MI and MII formation here were anomalies, largely because Tsutsui (1989) has presented convincing data that complete meiotic maturation in vivo in the dog requires at least 48 h. Because spontaneous meiotic resumption in vivo has been shown to be associated with follicular atresia (Gougeon and Testart 1986), we speculate that the oocytes from the smaller follicles in our study were atretic that, in turn, contributed to their poorer developmental competence and lower metabolism.

To date, there has been little scientific attention directed towards the metabolic activity of individual oocytes at various stages of meiotic maturation. It is known that metabolism in cat oocytes increases as the gamete progresses from the GV to MI to MII stage during in vitro culture (Spindler et al. 2000). In cattle, the utilization of pyruvate peaks at 12 h and declines by 24 h of incubation, the latter a time coincidental with ~80% of oocytes being at the MII stage (Steeves and Gardner 1999). In contrast, glycolytic metabolism in cow oocytes progressively increases with duration of the culture interval. Our observations here that glycolytic rate increases in dog oocytes progressing through meiotic maturation indicated that this metabolic pathway appeared crucial for gamete development in this species. This finding was especially apparent for oocytes from small and medium follicles, and the lack of a similar robust reaction in those from large follicles may well have been related to the few available oocytes (i.e., 3–6) per meiotic stage for that comparative evaluation.

We also confirmed that glycolysis was tightly associated with meiotic competence of the dog oocyte. Those that failed to resume meiosis and reach MII at 48 h had lower glycolysis than those that developed normally. Additionally, the dog was substantially different than the cat (Spindler et al. 2000) as the rate of glucose oxidation in the latter was a major determining factor in achieving meiosis. In our study, glucose oxidation rate remained constant throughout the 48 h culture and did not vary among meiotic stages. Thus, we concluded that the role(s) of glucose oxidation in oocyte nuclear maturation was not conserved across carnivore species, at least between the cat and dog. The latter species also was different from earlier studied mammals in that the oocyte metabolized glucose via glycolysis at a comparatively high rate, ~10-fold greater than that reported for the cat (Spindler et al. 2000), cow (Steeves and Gardner 1999) and mouse (Downs and Utecht 1999). Glucose uptake into the oocyte occurs via facilitative glucose transporters (GLUT; Purcell and Moley 2009) in the mouse (Purcell and Moley 2009), cow (Augustin et al. 2001), sheep (Pisani et al. 2008), human (Dan Goor et al. 1997) and rhesus monkey (Zheng et al. 2007). But oocytes from these species also have limited capacity to utilize this substrate (Brinster 1971; Purcell and Moley 2009; Steeves and Gardner 1999; Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010), possibly due to insufficient cytoplasmic phosphofructokinase, an essential glycolytic enzyme (Cetica et al. 2002). Nonetheless, most mammalian species appear to rely on cumulus cells that contain substantial GLUT and phosphofructokinase to convert glucose into readily utilized pyruvate (Biggers et al. 1967; Sutton-McDowall et al. 2010). No studies on glucose transporter expression or glycolytic enzyme activities have been conducted for dog oocytes. But given their comparatively high rate of glucose metabolism, we speculate that this specific gamete may have (1) high GLUT expression and/or (2) substantial concentrations of intra-cytoplasmic glycolytic enzyme(s), both of current research interest in our laboratory.

Dog oocytes recovered from the largest size follicles also expressed a higher glycolytic rate than those from smaller counterparts during the first 24 h of culture. At the time of release from the source follicle, oocytes from the largest also were experiencing the highest glucose oxidation rate. As significantly more of these oocytes had the capacity to achieve nuclear maturation, we reasoned that glucose metabolism likely was closely linked to developmental competence of the gamete. Such a finding is consistent with what has been reported for the mouse (Preis et al 2005), cat (Spindler et al. 2000), cow (Krisher and Bavister 1999; Preis et al. 2005; Steeves and Gardner 1999) and pig (Krisher et al. 2007) where glycolytic rate is intimately associated with oocyte developmental capacity. We suspect that the poor developmental ability of dog oocytes from small follicles may be associated with an inherent inability to effectively utilize already present glucose. This assertion is bolstered by investigations of others, including studies that demonstrate that pharmacological stimulation of glucose metabolism enhances the developmental competence of cow (Krisher and Bavister 1999) and pig (Herrick et al. 2006) oocytes. Thus, with the present new information, one logical next step would be to determine if altering culture conditions, including by supplementing with a pharmacological activator, would bolster glucose metabolism and enhance in vitro nuclear maturation success.

Our findings revealed that the dog oocyte oxidizes glucose and generally at rates comparable to those reported for the cow (Krisher and Bavister 1999) and cat (Spindler et al. 2000). However, glucose oxidation did not appear to play a key role in dog oocyte maturation as consumption was no different among oocytes derived from different follicle sizes or at varying stages of meiosis. At 24 and 48 h of oocyte in vitro culture, glucose oxidation was minimal compared to the robust rate of glycolysis. This observation may suggest that glucose was being converted to pyruvate that, in turn, was transformed into lactate that then was exported from the oocyte rather than entering the TCA cycle and undergoing oxidative metabolism (Preis et al. 2005; Sutton-McDowall et al. 2004). Such a phenomenon has been documented in mouse (Clough and Whittingham 1983), sheep (Gardner et al., 1993) and cattle (Rieger 1996) embryos. The finding that glucose oxidation may not play a key role in dog oocyte maturation confirms our previous finding that adding pyruvate (i.e., the substrate of the TCA cycle) to maturation medium does not improve nuclear maturation in the oocytes of this species (Songsasen et al., 2007). It also was possible that dog oocytes may have metabolized glucose through the PPP, which has been shown to regulate meiotic maturation of the mouse oocyte (Downs and Utecht 1999). An examination of lactate production and the role(s) of PPP in dog oocyte maturation are worthy of attention.

It is well established that oxidative metabolism of pyruvate through the TCA cycle is the primary pathway for energy production during oocyte maturation (Krisher et al. 2007; Purcell and Moley 2009). Because ATP is critical for oocyte acquisition of developmental competence, the TCA is recognized to play a vital role in oogenesis, especially in the mouse (Downs et al. 2002; Johnson et al. 2007) and cow (Rieger and Loskutoff 1994; Steeves and Gardner 1999). Although the cat oocyte preferentially metabolizes pyruvate, the rate of metabolizing this substrate is not correlated with nuclear maturation (Spindler et al. 2000). This is somewhat similar to the dog in that pyruvate uptake did not depend on meiotic stages. However, we demonstrated that, compared to small and medium counterparts, oocytes from large follicles were experiencing higher pyruvate uptake at the onset of culture, a difference that disappeared during the remainder of the incubation interval. Because oocytes from large follicles achieved nuclear maturation at a higher rate, we conclude that pyruvate may play some valuable role(s) in nuclear maturation of the dog oocyte. Because these particular gametes metabolize glucose via glycolysis at a high rate, intracellular production of pyruvate may be sufficient to support oocyte development without requiring a substantial need for this substrate from an exogenous source. Nonetheless, we see value in future studies that (1) directly measure pyruvate utilization and (2) assess meiotic status of gametes cultured in medium supplemented with this substrate alone (i.e., in the absence of glucose) for elucidating the role of this substrate on dog oocyte nuclear maturation.

Oocytes also oxidatively metabolize amino acids, especially glutamine (Bae and Foote 1974; Newsholme et al. 2003), which is recognized as a key substrate for cellular processes, including glutathione synthesis, protein translation and gluconeogenesis (Newsholme et al. 2003). Glutamine oxidation in cow oocytes is maximal at 18 to 24 h of in vitro culture, appearing critical for promoting final nuclear maturation in this species (Rieger and Loskutoff 1994) as well as in the rhesus monkey (Zheng et al. 2002). One of our earlier studies demonstrated that glutamine uptake also peaks at about 12 h after the onset of culturing dog oocytes (Songsasen et al. 2007). In the present study, there clearly was higher glutamine metabolism in gametes derived from large follicles compared to small and medium counterparts. Due to these findings and especially because the highest glutamine oxidation occurred in MII oocytes recovered from the largest follicles, it was apparent that metabolism of this amino acid was important in dog oocyte maturation. However, because we have previously found that supplementing the culture medium with glutamine has no impact on achieving MII status (Songsasen et al. 2007), we speculate that this amino acid may be involved in cytoplasmic maturation, for example, promoting the synthesis of proteins critical for fertilization, pronuclear formation and embryonic development. This seems feasible given that adding glutamine to culture medium is known to promote monospermic fertilization and pronuclear formation of the immature pig oocyte (Hong and Lee 2007).

In summary, the domestic dog differs from more traditionally studied species, including laboratory rodents and livestock, in that the oocyte metabolically uses glucose at a high rate via glycolysis. Additionally, the developmental ability of the oocyte to achieve nuclear maturation is tightly associated with metabolism of glucose and glutamine. As a result of our findings, the next logical steps would be to assess the levels of GLUT expression and intra-cytoplasmic glycolytic enzyme as well as determining the role(s) of PPP on in vitro nuclear maturation success. As glycolysis seems to be such a key metabolic pathway for the dog oocyte, it also appears prudent to explore the influence of altering culture conditions, for example by supplementing with follicle stimulating hormone (Sutton-McDowall et al. 2004) and/or a glycolytic stimulator such as dinitrophenol (Herrick et al. 2006). Finally, this scholarly information has substantial practical application, in part, due to the uniqueness of the dog and other canid species that are only occasionally sexually active, usually once or twice annually. The ability to successfully recover, mature and fertilize intraovarian oocytes is recognized as an important strategy for rescuing germplasm that normally will never contribute to ‘normal’ reproduction (Comizzoli et al. 2010). This need is especially apparent for propagating dogs used as models for examining human diseases (Schneider et al. 2008) as well as for improved conservation of wild canids where seven of 36 species are listed as threatened with extinction (IUCN 2010). The fundamental data generated in the present study underpin our long-term goal to use intragonadal oocytes for propagating genetically valuable canid genotypes and rare species.

Materials and Methods

Ovarian oocyte collection

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated. Oocytes were recovered from the paired ovaries of 100 dogs (age, 6 mo – 6 yr) that were experiencing various stages of the reproductive cycle, all of which were undergoing ovariohysterectomy at veterinary hospitals in the Northern Virginia area. Ovaries were placed immediately in 0.9% (w/v) NaCl containing 0.06 mg/ml penicillin G sodium and 0.06 mg/ml streptomycin and transported at room temperature (~22°C) to our laboratory (near Front Royal, VA). Within 6 h of excision, ovaries were sliced into ~5 mm sections and individual follicles manually isolated. Follicles were divided into three size classes based on our previous observations (Songsasen and Wildt, 2005) and actual measurements using a stage micrometer: small, < 1 mm in diameter (n = 320); medium, 1 to < 2 mm (n = 290); and large, ≥ 2 mm (n = 80). Each follicular wall was dissected with a 20 gauge needle to allow recovering the cumulus oocyte complex that then was placed in TCM 199 with 25mM HEPES. Because we had previously determined that the dog oocyte reaches its maximal size (~250 μm diameter) in the early antral follicular stage (Songsasen et al. 2009), the size of individual, recovered gametes was not determined. Only oocytes exhibiting homogenous dark cytoplasm with two or more layers of cumulus cells and with a comparable size were used (Songsasen et al. 2003).

In vitro culture of oocytes

In vitro culture of oocytes was performed using methods previously developed in our laboratory (Songsasen et al. 2003). Briefly, before culturing, all oocytes were washed twice in TCM 199 + 25μM β-mercaptoethanol + 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor + 0.25 mM pyruvate + 2.0 mM glutamine + 0.1% polyvinyl alcohol + 0.03 mg/ml streptomycin + 0.03 mg/ml penicillin G sodium (IVM medium). After an initial 1 h incubation in IVM medium supplemented with 5 IU/ml equine chorionic gonadotropin, each oocyte was cultured in a fresh 100 μl droplet of IVM medium (38.5°C in 5% CO2) for 0, 24 or 48 h. No more than nine oocytes were cultured per droplet. Although it has been shown that nuclear maturation of dog oocytes occurs from 48 to 127 h in vivo (Tsuitsui 1989; Reynaud et al. 2005), earlier findings from our laboratory (Songsasen et al. 2003) as well as others (Yamada et al. 1993; Nickson et al. 1993; Saint Dizier et al., 2004) have shown that culturing dog oocytes for > 48 h does not increase the number of MII oocytes produced. Therefore, we chose the end-point of 48 h of culture for the present study. Experiments were replicated at least three times for each follicle group and culture interval.

Oocyte metabolism assessments

Analysis of oocyte metabolism was conducted using the hanging drop method as previously described (O’Fallon and Wright 1986; Spindler et al. 2000; Songsasen et al. 2007). At the end of the culture interval (see above), cumulus cells were removed from each oocyte by gentle pipetting and then the gamete washed three times in TCM 199 + 25 mM HEPES. Oocytes were individually placed in the IVM medium supplemented with (1) 1.0 mM pyruvate + 1 mM glucose (D-[5-3H]-glucose = 0.005 mM, 0.080 to 0.085 μCi/μl; D-[6-14C] glucose = 0.095 mM, 0.055 to 0058 μCi/μl) or (2) 0.001 mM [0.043 μCi/μl] L-[G-3H]-glutamine + 1 mM [1-14C] pyruvate (0.0.027 μCi/μl; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences. Piscataway, NJ). Each oocyte was aspirated into 3 μl of medium using a displacement pipette and placed onto a lid of an Eppendorf® microcentrifuge tube that was closed over a tube containing 1.5 ml of 25 mM NaHCO3. Three more tubes were incubated with medium alone to determine passive transfer of radioisotope to the NaHCO3 trap (baseline). An additional three tubes had medium mixed into the trap solution to determine total medium radioactivity in pmol. After 3 h of incubation (at 38.5°C), 1 ml of the NaHCO3 trap was removed, added to vials containing 3 ml of scintillation fluid (Ultima Gold; Packard, Meriden, CT) and counted on a dual-label channel of a β-counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA). The amount of emerging 14CO2 and/or 3H20 (in pmols) as a result of individual oocyte metabolism was determined by subtracting the average baseline value and dividing by the DPM value for 1 pmol of each substrate.

Using the dual-label setting, it was possible to measure 14C and 3H simultaneously. [D-53H]- and [D-614C] glucose (measuring glycolysis and glucose oxidation, respectively) were quantified together as were [1-14C] pyruvate and L-[G-3H]-glutamine (measuring pyruvate uptake and glutamine oxidation, respectively).

Nuclear status assessments

After metabolic analysis, individual oocytes were fixed by placement into wells containing 1:3 acetic acid:ethanol solution for 48 h. Each then was stained using aceto-orcein (1% [w/v] orcein in 45% [v/v] acetic acid) and washed in aceto-glycerol (1:1:3 glycerol:acetic acid:distilled water). Nuclear status was evaluated under light microscopy with oocytes categorized as being at one of the following stages: GV, GVBD, MI, anaphase/telophase I (AI/TI), MII or pronucleus (i.e., parthenote; PN). Detailed descriptions of each of these stages are available in earlier publications (Songsasen et al. 2005, 2007).

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). Proportional data of meiotic status were subjected to arcsine transformation before statistical analysis. Metabolic activity comparisons among oocytes from the three follicle groups and meiotic stages were conducted using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA (for non-parametric data) followed by a multiple comparison for all pair-wised evaluations (SigmaStat, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). Evaluations of metabolic activities across meiotic stage within the same culture interval were performed using Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA. The level of significance was set at 95%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the New Town Veterinary Clinic, Animal Medical Center, Stephen City Animal Hospital, Cedarville Veterinary Clinic, Royal Oak Animal Clinic, Warren County Veterinary Clinic, Linden Heights Animal Hospital and Winchester Animal Hospital for providing dog ovaries for this study.

Grant sponsor: the National Institutes of Health; Grant number: KO1RR020564.

List of abbreviations

- GV

germinal vesicle

- GVBD

germinal vesicle breakdown

- MI

metaphase

- AI/TI

anaphase/telophase I

- MII

metaphase II

- PN

parthenote

- h

hour(s)

- mo

month(s)

- IVM

in vitro maturation

- COC

cumulus oocyte complex

- PPP

pentose-phosphate- pathway

- TCA

tricaboxylic acid cycle

- GLUT

glucose transporters

- SEM

standard error of mean

References

- Alhaider AK, Watson PF. The effects of hCG and growth factors on in vitro nuclear maturation of dog oocytes obtained during anoestrus. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2009;21:538–548. doi: 10.1071/RD08167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin R, Pocar P, Navarrete-Santos A, Wrenzycki C, Gandolfi F, Niemann H, Fischer B. Glucose transporter expression is developmentally regulated in in vitro derived bovine preimplantation embryos. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60:370–376. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae I-H, Foote RH. Utilization of glutamine for energy and protein synthesis by cultured rabbit follicular oocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1974;90:432–436. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(75)90333-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggers JD, Whittingham DG, Donahue RP. The pattern of energy metabolism in the mouse oocyte and zygote. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1967;58:560–567. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.2.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolamba D, Borden-Russ KD, Durrant BS. In vitro maturation of domestic dog oocytes cultured in advanced preantral and early antral follicles. Theriogenology. 1998;49:933–942. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(98)00042-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster RL. Oxidation of pyruvate and glucose by oocytes of the mouse and rhesus monkey. J Reprod Fertil. 1971;24:187–191. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0240187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetica P, Pintos L, Dalvit G, Beconi M. Activity of key enzymes involved in glucose and triglyceride catabolism during bovine oocyte maturation in vitro. Reproduction. 2002;124:675–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough JR, Whittingham DG. Metabolism of [14C]glucose by postimplantation mouse embryos in vitro. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1983;74:133–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comizzoli P, Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Protecting and extending fertility for females of wild and endangered mammals. Cancer Treat Res. 2010;156:87–100. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-6518-9_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Concannon PW, McCann JP, Temple M. Biology and endocrinology of ovulation, pregnancy and parturition in the dog. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1989;39:3–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan-Goor M, Sasson S, Davarashvili A, Almagor M. Expression of glucose transporter and glucose uptake in human oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2508–2510. doi: 10.1093/humrep/12.11.2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominko T, First NL. Timing in meiotic progression in bovine oocytes and its effect on early embryo development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;47:456–467. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199708)47:4<456::AID-MRD13>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SM. The influence of glucose, cumulus cells and metabolic coupling on ATP levels and meiotic control in the isolated mouse oocytes. Dev Biol. 1995;167:502–512. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SM, Humpherson PG, Leese HJ. Pyruvate utilization by mouse oocytes is influenced by meiotic status and the cumulus oophorus. Mol Reprod Dev. 2002;62:113–123. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs SM, Utecht AM. Metabolism of radiolabeled glucose by mouse oocytes and oocyte-cumulus cell complexes. Biol Reprod. 1999;60:1146–1452. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod60.6.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards RG, Gates AH. Timing of the stages of the maturation divisions, ovulation, fertilization and the first cleavage of eggs of adult mice treated with gonadotrophins. J Endocrinol. 1959;18:292–304. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.0180292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evecen M, Cirit U, Demir K, Hamzaoğlu Aİ, Bakirer G, Pabuccuoğlu S, Birler S. Adding hormones sequentially could be an effective approach for IVM of dog oocytes. Theriogenology. 2011;75:1647–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2011.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia J, Han D, Sancheti H, Yap LP, Kaplowitz N, Cadenas E. Regulation of mitochondrial glutathione redox status and protein glutathionylation by respiratory substrates. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:39646–39654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.164160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner DK, Lane M, Batt P. Uptake and metabolism of pyruvate and glucose by individual sheep preattachment embryos developed in vivo. Mol Reprod Dev. 1993;36:313–319. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080360305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godard NM, Pukazhenthi BS, Wildt DE, Comizzoli P. Paracrine factors from cumulus-enclosed oocytes ensure the successful maturation and fertilization in vitro of denuded oocytes in the cat model. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2051–2060. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gougeon A, Testart J. Germinal vesicle breakdown in oocytes of human atretic follicles during the menstrual cycle. J Reprod Fertil. 1986;78:389–401. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0780389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick JR, Brad AM, Krisher RL. Chemical manipulation of glucose metabolism in porcine oocytes: effects on nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation in vitro. Reproduction. 2006;131:289–298. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Lee E. Intrafollicular amino acid concentration and the effect of amino acids in a defined maturation medium on porcine oocyte maturation, fertilization and preimplantation development. Theriogenology. 2007;68:728–735. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUCN. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2010.3. 2010 < http://www.iucnredlist.org>. Downloaded on 23 October 2010.

- Johnson MT, Freeman EA, Gardner DK, Hunt PA. Oxidative metabolism of pyruvate is required for meiotic maturation of murine oocytes in vivo. Biol Reprod. 2007;77:2–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.059899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatun M, Bhuiyan MM, Ahmed JU, Hague A, Rahman MB, Shamsuddin M. In vitro maturation and fertilization of prepubertal and pubertal black Bengal goat oocytes. J Vet Sci. 2011;12:75–82. doi: 10.4142/jvs.2011.12.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MK, Fibrianto YH, Oh HJ, Jang G, Kim HJ, Lee KS, Kang SK, Lee BC, Hwang WS. Effect of β-mercaptoethanol or epidermal growth factor supplementation on in vitro maturation of canine oocytes collected from dogs with different stages of the estrus cycle. J Vet Sci. 2004;5:253–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T, Matsuura K, Naruse K, Funahashi H. In vitro culture with a tilting device in chemically defined media during meiotic maturation and early development improves the quality of blastocysts derived from in vitro matured and fertilized porcine oocytes. J Reprod Dev. 2010;56:552–557. doi: 10.1262/jrd.10-041h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisher RL, Bavister BD. Enhanced glycolysis after maturation of bovine oocytes in vitro is associated with increased developmental competence. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;53:19–26. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199905)53:1<19::AID-MRD3>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krisher RL, Brad AM, Herrick JR, Sparman ML, Swain JE. A comparative analysis of metabolism and viability in porcine oocytes during in vitro maturation. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007;98:72–96. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luvoni GC, Luciano AM, Modina S, Gandolfi F. Influence of different stages of the oestrous cycle on cumulus-oocyte communications in canine oocytes: effects on the efficiency of in vitro maturation. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 2001;57:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahi CA, Yanagimachi R. Maturation and sperm penetration of canine ovarian oocytes in vitro. J Exp Zool. 1976;196:189–195. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401960206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín Bivens CL, Lindenthal B, O’Brien MJ, Wigglesworth K, Blume T, Grøndahl C, Eppig JJ. A synthetic analogue of meiosis-activating sterol (FF-MAS) is a potent agonist promoting meiotic maturation and preimplantation development of mouse oocytes maturing in vitro. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2340–2344. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Lima MMR, Procopio J, Pithon-Curi TC, Doi SQ, Bazotte RB, Curi R. Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36:153–163. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickson DA, Boyd JS, Eckersall PD, Ferguson JM, Harvey MJ, Renton JP. Molecular biological methods for monitoring oocyte maturation and in vitro fertilization in bitches. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1993;47:231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’ Fallon JV, Wright R. Quantitative determination of the pentose phosphate pathway in preimplantation mouse embryos. Biol Reprod. 1986;34:58–64. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod34.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otoi T, Fujii M, Tanaka M, Ooka A, Suzuki T. Canine oocyte diameter in relation to meiotic competence and sperm penetration. Theriogenology. 2000;54:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0093-691x(00)00368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phemister RD, Holst PA, Spano JS, Hopwood ML. Time of ovulation in the Beagle bitch. Biol Reprod. 1973;8:74–82. doi: 10.1093/biolreprod/8.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani LF, Antonini S, Pocar P, Ferrari S, Brevini TA, Rhind SM, Gandolfi F. Effects of pre-mating nutrition on mRNA levels of developmentally relevant genes in sheep oocytes and granulosa cells. Reproduction. 2008;136:303–312. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preis KA, Seidel G, Gardner DK. Metabolic markers of developmental competence for in vitro-matured mouse oocytes. Reproduction. 2005;130:475–483. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell SH, Moley KH. Glucose transporters in gametes and preimplantation embryos. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009;20:483–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynaud K, Fontbonne A, Marseloo N, Thoumire S, Chebrout M, de Lesegno CV, Chastant-Maillard S. In vivo meiotic resumption, fertilization and early embryonic development in the bitch. Reproduction. 2005;130:193–201. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieger D. The metabolic activity of cattle oocytes and early embryos. J Reprod Dev (Suppl) 1996;42:85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Rieger D, Loskutoff NM. Changes in the metabolism of glucose, pyruvate, glutamine and glycine during maturation of cattle oocytes in vitro. J Reprod Fertil. 1994;100:257–262. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1000257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues BA, Silva AEF, Rodriguez P, Cavalcante LF, Rodrigues JL. Cumulus cell features and nuclear chromatin configuration of in vitro matured canine COCs and the influence of in vivo serum progesterone concentrations of ovary donors. Zygote. 2009;17:79–91. doi: 10.1017/S096719940800508X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint-Dizier M, Renard J-P, Chastant-Maillard S. Induction of final maturation by sperm penetration in canine oocytes. Reproduction. 2001;121:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider MR, Wolf E, Braun J, Kolb H-J, Adler H. Canine embryo-derived stem cells and models for human diseases. Hum Mol Gent. 2008;17:R42–R47. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimazu Y, Yamada S, Kawano Y, Kawaji H, Nakazawa M, Maito K, Toyoda Y. In vitro capacitation of canine spermatozoa. J Reprod Dev. 1992;38:67–71. [Google Scholar]

- Shirazi A, Shams-Esfandabadi N, Admadi E, Heidari B. Effects of growth hormone on nuclear maturation of ovine oocytes and subsequent embryo development. Reprod Dom Anim. 2010;45:530–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2008.01290.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva AE, Cavalcante LF, Rodrigues BA, Rodrigues JL. The influence of powdered coconut water (ACP-318®) in in vitro maturation of canine oocytes. Reprod Dom Anim. 2010;45:1042–1046. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirard MA, Parrish JJ, Ware CB, Leibfried-Rutledge ML, First NL. The culture of bovine oocytes to obtain developmentally competent embryos. Biol Reprod. 1988;39:546–552. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod39.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Fickes A, Pukazhenthi P, Wildt DE. Follicular morphology, oocyte diameter and localisation of fibroblast growth factors in the domestic dog ovary. Reprod Domest Anim (Suppl) 2009;2:65–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2009.01424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Spindler RE, Wildt DE. Requirement for, and patterns of, pyruvate and glutamine metabolism in the domestic dog oocyte in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 2007;74:870–877. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Size of the donor follicle, but not stage of reproductive cycle or seasonality, influences meiotic competency of selected domestic dog oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;72:113–119. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Wildt DE. Oocyte biology and challenges in developing in vitro maturation systems in the domestic dog. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007;98:2–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anireprosci.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Songsasen N, Yu I, Gomez M, Leibo SP. Effects of meiosis -inhibiting agents and equine chorionic gonadotropin on nuclear maturation of canine oocytes. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003;65:435–445. doi: 10.1002/mrd.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler RE, Pukazhenthi BS, Wildt DE. Oocyte metabolism predicts the development of cat embryos to blastocyst in vitro. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;56:163–171. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(200006)56:2<163::AID-MRD7>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves TE, Gardner DK. Metabolism of glucose, pyruvate and glutamine during the maturation of oocytes derived from pre-pubertal and adult cows. Mol Reprod Dev. 1999;54:92–101. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199909)54:1<92::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-McDowall ML, Gilchrist RB, Thompson JG. Cumulus expansion and glucose utilisation by bovine cumulus-oocyte complexes during in vitro maturation: the influence of glucosamine and follicle-stimulating hormone. Reproduction. 2004;128:313–319. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton-McDowall ML, Gilchrist RB, Thompson JG. The pivotal role of glucose metabolism in determining oocyte developmental competence. Reproduction. 2010;139:685–695. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui T. Gamete physiology and timing of ovulation and fertilization in dogs. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1989;39:269–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildt DE, Panko WB, Chakraborty PK, Seager SWJ. Relationship of serum estrone, estradiol-17β and progesterone to LH, sexual behaviors and time of ovulation in the bitch. Biol Reprod. 1979;20:648–658. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod20.3.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada S, Shimazu Y, Kawano Y, Nakazawa M, Naito K, Toyoda Y. In vitro maturation and fertilization of preovulatory dog oocytes. J Reprod Fertil (Suppl) 1993;47:227–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng P, Vassena R, Latham KE. Effects of in vitro oocyte maturation and embryo culture on the expression of glucose transporters, glucose metabolism and insulin signaling genes in rhesus money oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Mol Hum Reprod. 2007;13:361–371. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gam014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.