Abstract

The SMRT and NCoR corepressors bind to, and mediate transcriptional repression by, many nuclear receptors. Both SMRT and NCoR are expressed by alternative mRNA splicing, generating a series of structurally and functionally distinct corepressor “variants.” We report that a splice variant of SMRT, SMRTε, recognizes a restricted subset of nuclear receptors. Unlike the other corepressor variants characterized, SMRTε possesses only a single receptor interaction domain (RID) and exhibits an unusual specificity for a subset of nuclear receptors that includes the retinoic acid receptors (RARs). The ability of the single RID in SMRTε to efficiently interact with RARs appears to be enhanced by a recently recognized β-strand/β-shrand interaction between corepressor and receptor. We suggest that alternative mRNA splicing of corepressors can restrict their function to specific nuclear receptor partnerships, and we propose that this may serve to customize the transcriptional repression properties of different cell types for different biological purposes.

Keywords: Corepressors, nuclear receptors, alternative-mRNA splicing, SMRT, retinoic acid receptors, β-strand

1. INTRODUCTION

Nuclear receptors are a large family of ligand regulated transcription factors that control key aspects of animal reproduction, development, and homeostasis (e.g. (Flamant et al., 2006, Glass and Saijo, 2011, Hager, 2001, McEwan, 2009, Sonoda et al., 2008)). Nuclear receptors bind to specific DNA sequences, bind to small, hydrophobic ligands, and regulate transcription of nearby target genes. Nuclear receptors arose early in the evolution of animals and appear to have gained their current diversity through cycles of gene duplication and divergence (Bertrand et al., 2004, Bertrand et al., 2007). Over 48 different nuclear receptors have been identified in the human genome (49 in the mouse genome), and include receptors for traditional endocrine and paracrine hormones, for intracellular metabolic intermediates, and for xenobiotics (Flamant et al., 2006, Glass and Saijo, 2011, Hager, 2001, McEwan, 2009, Sonoda et al., 2008). Additional “orphan” members of the nuclear receptor family either appear to bind ligand constitutively or may not bind any ligand (Benoit et al., 2006).

Many of the nuclear receptors are bimodal in their transcriptional regulatory properties, and they can either enhance or suppress expression of a given target gene by recruiting auxiliary proteins that serve as coactivators or as corepressors (Buranapramest and Chakravarti, 2009, Lonard and O’Malley B, 2007, Savkur et al., 2004, Tsai and Fondell, 2004). Coactivators place activating marks in the chromatin, help recruit components of the general transcriptional machinery, and/or alter nucleosome structure through ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling. Corepressors possess (or tether) reciprocal enzymatic activities that render chromatin a less effective substrate for transcription and/or interfere with the general transcriptional machinery.

SMRT and NCoR are genetic paralogs that mediate transcriptional repression by many members of the nuclear receptor family (Jones and Shi, 2003, Lazar, 2003, Moehren et al., 2004, Ordentlich et al., 2001, Perissi et al., Privalsky, 2004, Stanya and Kao, 2009). The SMRT and NCoR proteins serve as crucial nucleating molecules that recruit an array of enzymatic and architectural proteins into a larger corepressor assembly. These additional corepressor subunits include histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3), TBL1, TBLR1, and GPS2, and they bind primarily to interaction surfaces within the N-terminal and central regions of NCoR and SMRT (Guenther and Lazar, 2003, Li et al., 2000, Nagy et al., 1997, Wen et al., 2000, Yoon et al., 2003, You et al., 2010). The corepressor holo-complex is then tethered to its nuclear receptor partners through receptor interaction domains (RIDs) that map primarily to the SMRT and NCoR C-terminal region (Cohen et al., 2001, Downes et al., 1996, Li et al., 1997, Muscat et al., 1998, Seol et al., 1996, Wong and Privalsky, 1998). Each RID possess an α-helical CoRNR box that can dock with a hydrophobic groove found on the surface of its nuclear receptor partners; the sequence of the CoRNR boxes and flanking sequences in each RID, therefore, determine whether the corepressor holocomplex can interact with, and mediate repression by, a given nuclear receptor or not (Burke et al., 1998, Hodgson et al., 2008, Hu et al., 2001, Makowski et al., 2003, Marimuthu et al., 2002, Perissi et al., 1999, Webb et al., 2000, Xu et al., 2002).

Many nuclear receptors are expressed from multiple, interrelated genetic loci and by alternative mRNA splicing to produce a series of protein variants or isoforms that differ in their biochemical properties in vitro and in their biological functions in cells (Flamant et al., 2006, Glass and Saijo, Hager, 2001, McEwan, 2009, Sonoda et al., 2008). Similar diversification exists among the coregulator families that mediate the actions of these receptors. SMRT and NCoR, for example, are expressed from two distinct genes and share approximately 50% identity at the amino acid level (Horlein et al., 1995, Chen and Evans, 1995, Ordentlich et al., 1999, Sande and Privalsky, 1996, Seol et al., 1996). Alternative mRNA splicing at both corepressor loci generates additional diversity, yielding multiple SMRT and NCoR protein variants that differ in their amino acid sequence, in their preference for specific nuclear receptor partners, in their response to kinase regulatory pathways, and in their tissue expression patterns (Faist et al., 2009, Goodson et al., 2005a, Goodson et al., 2005b, Jonas et al., 2007, Malartre et al., 2004, Muscat et al., 1998, Short et al., 2005).

Most nuclear receptors bind to their target genes as protein dimers (although other modes are known, including monomers, oligomers, and tethering through other transcription factors). It has been generally accepted that each receptor in the dimer contacts a separate RID domain on a single SMRT or NCoR protein; by this model, two RID domains should be required for efficient recruitment of the corepressor complex (e.g. (Cohen et al., 1998, Downes et al., 1996, Ghosh et al., 2002, Hu et al., 2001, Machado et al., 2009, Makowski et al., 2003, Zamir et al., 1997b)). Consistent with this, the majority of known SMRT and NCoR splice variants possess at least two RIDs. However, one recently recognized SMRT splice variant, denoted SMRTε in our nomenclature, possesses only one RID (Faist et al., 2009, Goodson et al., 2005a, Short et al., 2005), and would therefore be predicted to be unable to bind to nuclear receptors by the prevailing interaction model. We report here that SMRTε binds to a relatively limited subset of nuclear receptors in solution, including retinoic acid receptors (RARs), thyroid hormone receptors (TRs), Rev-Erbα, and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF) II. Notably, only RARs retain the strong SMRTε interaction when these receptors are further allowed to assemble into dimers on their cognate DNA response elements. The interaction of SMRTε with RARs appears to be enhanced by a recently elucidated β-strand/β-strand contact surface that works in addition to the previously identified α-helical/groove contacts (le Maire et al., 2010, Phelan et al., 2010). We propose that SMRTε is a specialized corepressor splice variant customized during evolution to function with a limited subset of nuclear receptors, and that alternative mRNA splicing in different tissues creates cell-specific, receptor-specific repression programs.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. DNA Constructs

The C-terminal amino acids of SMRTε (amino acids 1851–2393) were subcloned in frame to the GST gene in pGEX in order to express GST-SMRTε as a fusion protein. The GST-SMRTε β-strand mutation, V2141P, CoRNR Box mutation of amino acids 2092–2096 from IXXII to IXXAA, the RARα-I396E mutation, and the TRα1-L386E mutation were created using the Quick Change site-directed mutagenesis protocol from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA).

2.2. Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction (rtPCR)

RT-PCR was performed using primer pairs spanning the alternatively-spliced exon 44. This resulted in three distinctly sized DNA products, with the relative abundance of each reflecting the relative abundance of the corresponding alternatively spliced exon (44-, 44b−, and 44b+) in the mRNA population. The bands were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis, stained by ethidium bromide, and quantified by image analysis (Mengeling et al., 2011). The relative ratios of the different PCR products, being internally controlled, was reproducible over a range of input dilutions and for different primer pairs.

2.3. Protein-Protein Interaction Assays

Nuclear receptors were transcribed and translated in vitro in the presence of 35S-methionine using either the TNT T7 Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System or the TNT SP6 High-Yield Protein Expression System following the manufacturer’s protocols (Promega, Madison, WI). Glutathionine-S-Transferase-corepressor fusion proteins (GST-CoR) encompassing the C-terminal receptor interaction domains of the different corepressor variants were expressed from baculovirus in Sf9 cells for 72 h at 28 °C, and cell lysates were isolated as previously described (Mengeling et al., 2011). Alternatively, for analysis of the β-strand/β-strand interactions, GST-CoR fusions were expressed in BL-21 E. coli overnight at 16 °C after induction with 1 mM IPTG at an A600 value of 0.8–1.0 and cell lysates were made as described (Goodson et al., 2007). GST pulldown assays were adapted to a microplate format (Goodson et al., 2007). Briefly, radiolabeled NR (typically 1–3 μl of TNT reaction product per assay) was incubated at 4 °C with equal mass amounts of immobilized GST-CoR in 100 μl of Binding Buffer A (Goodson et al., 2007). The binding reactions were carried out in 96-well multiscreen filter plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA). After a 45 min incubation with end-over-end rotation at 4 °C, the filter wells were washed 3 times with 200 μl of ice-cold Buffer A, and bound radiolabeled proteins were then eluted with 50 μl of 20 mM glutathione in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8 at 4 °C for 45 min with end-over-end rotation. The eluted proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and were visualized and quantified using a PhosphorImager/STORM system (GE Healthcare) and the GraphPad Prism 5 statistical/plotting package (La Jolla, CA).

2.4. Repression Assays

CV-1 cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) formulated with high glucose and L-glutamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS (PAA, Dartmouth, MA). Cells were buffered with a bicarbonate/5% CO2 system and maintained at 37 °C. Transfections were performed in DMEM, 5% FBS (hormone-stripped) using 24-well culture plates and Effectene (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Each transfection employed 3 × 104 cells, plated the day prior to transfection; 30 ng of pGL4-CMV-2X-17mer luciferase reporter containing 2 iterations of the Gal4 DNA binding sequence; 10 ng of pSG5-GBD, pSG5GBD-RARα(LBD), pSG5GBD-LXRα(LBD), pSG5GBD-TRβ1(LBD), or pSG5GBD-Rev-Erbα (LBD) wherein the “ligand-binding” E/F domain of each nuclear receptor is fused in frame to the DNA binding domain of Gal4; 200 ng of pSG5HA-SMRTε, pSG5HA-NCoRω or empty pSG5HA vector; and 10 ng of pCMV-LacZ as an internal transfection efficiency control. A pSG5HA-SMRTε bearing mutations in either the α-helical CoRNR box or the adjacent β-strand region was used instead of the wild-type construct in several experiments. The medium was replaced 24h later with fresh DMEM, 5% hormone-stripped FBS. After a further 24 h, the cells were washed and lysed. Luciferase activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) with a Turner Design 20/20 luminometer. β-Galactosidase activity was measured using a chlorophenol-red-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG) substrate (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and a Molecular Devices SpectraMax 250 microplate reader.

2.5. Electrophoretic Mobility Supershift Assays

Oligonucleotide probes were for RARs and COUP TF II: consensus DR5 (top strand: 5′-agctA AAGGT CAgaA AAGGT CAgca gga-3′ bottom strand: 5′-tcgat cctgc TGACC TTTAT CTGAC CTTT-3′); for TRs: cLys F2 (top strand: 5′-tcgac ttatTGACCC cagctgAGGTC Aagttag-3′ bottom strand 5′-gaataA CTGGGgt cgacTCCA GTtcaatcagct-3′); for RevErbα: RevDR2 (Zamir et al., 1997a) (top strand: 5′-agctc caact AGGTC ACTAG GTCAa aggga -3′ bottom strand: 5′-tcgat ccctt TGACC TAGTG ACCTa gttgg-3′)(IDT, Coralville, IA). They were annealed and radiolabeled by Klenow polymerase fill-in using 32P-α-dGTP (3000 Ci/mmol, Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA) plus the three remaining unlabeled dNTPs. RARs and Rev-Erbα were expressed using the TNT SP6 High-Yield Protein Expression System following the manufacturer’s instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Three micrograms of plasmid were used per translation. hTRα1 and TRβ1 were expressed from recombinant baculovirus in Sf9 cells, and nuclear extracts were made as previously described (Mengeling et al., 2005, Phan et al. 2010). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) contained the nuclear receptor of interest, 1 pmol of radiolabeled probe, and the specified amount of GST-corepressor in 20μl binding buffer per reaction (Mengeling et al., 2011). Protein/DNA complexes were resolved by native electrophoresis at 200 V for 90 min. through a 4% polyacrylamide gel polymerized over an 8% polyacrylamide gel cushion, both buffered in 0.5X TBE (45 mM Tris-borate, 1 mM EDTA). Gels were visualized by Storm phophorimager analysis (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ).

3. RESULTS

3.1. SMRTε is expressed in a variety of tissues by alternative splicing

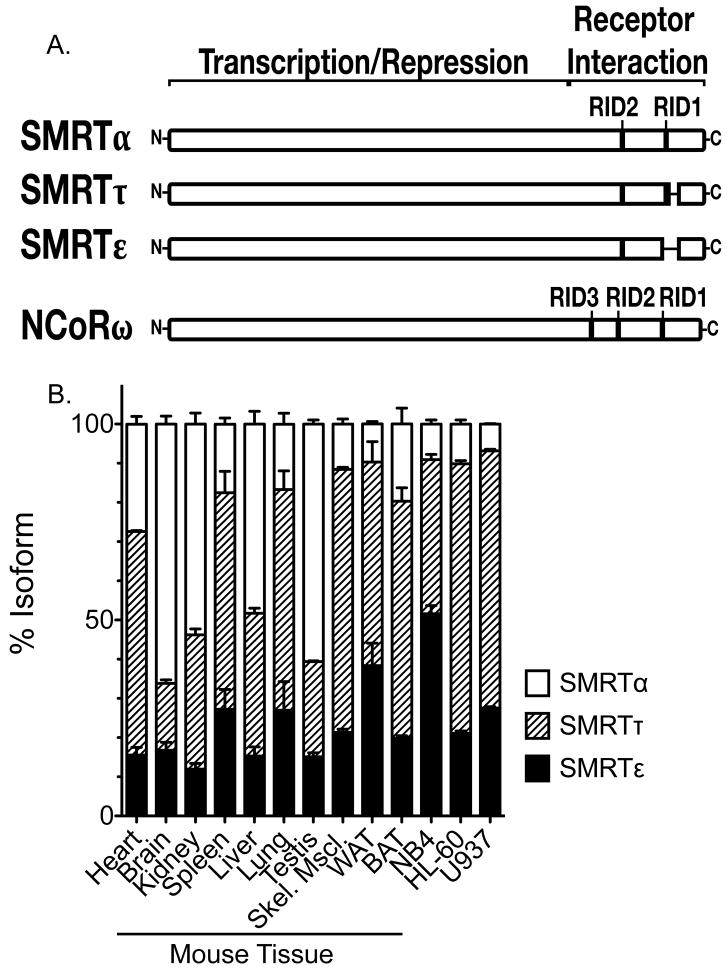

SMRTε is generated by utilization of an mRNA splice donor that excises exon 44 and produces an in-frame deletion of 228 nucleotides, representing 76 codons (Fig. 1A). This results in the complete loss of the C-terminal-most RID (denoted RID1 in Fig. 1A), a domain otherwise found in the much more widely studied SMRTα and SMRTτ splice forms (Goodson et al., 2005a, Short et al., 2005, Malartre et al., 2004). No equivalent splice form has been detected in the NCoR paralog ((Goodson et al., 2005a, Malartre et al., 2004) and MLG data not shown).

Fig. 1.

SMRTε is expressed in a wide variety of tissues and cell lines. (A) The proteins encoded by the SMRTε, SMRTτ, SMRTα, and NCoRω splice variants are depicted schematically. The protein sequences included in a given corepressor variant are shown as rectangles; sequences removed by splicing are indicated as lines. The location of the different C-terminal receptor interactions domains (RIDs) are also shown, as are the more N-terminal domains that mediate transcriptional repression by recruiting additional components of the corepressor complex. (B) The relative levels of expression of SMRTε, τ, and α in different cell lines and in different mouse tissues was determined by rt-PCR. Skel Mscl = skeletal muscle. WAT = white adipose tissue. BAT = brown adipose tissue. The mean and standard error from multiple independent experiments are shown.

We examined the abundance of the SMRTε splice variant in a variety of tissues and cell lines by utilizing rtPCR and oligonucleotide primers that span the splice site (Fig. 1B). We found that the 44- splice form is expressed in all mouse tissues examined, and represents 5 to 38% of the total SMRT mRNA. The highest SMRTε mRNA levels were observed in lung, spleen, skeletal muscle, and in white and brown adipose tissue. A similar range of abundance was observed in a variety of established human cell lines, with the exception of the human acute promyelocytic cell line NB4, where the 44- splice form represented a narrow majority of the total SMRT mRNA. These results indicate that SMRTε represents a significant percent of the total SMRT corepressor present in a wide variety of cell types.

3.2. SMRTε interacts with a distinct subset of nuclear receptors

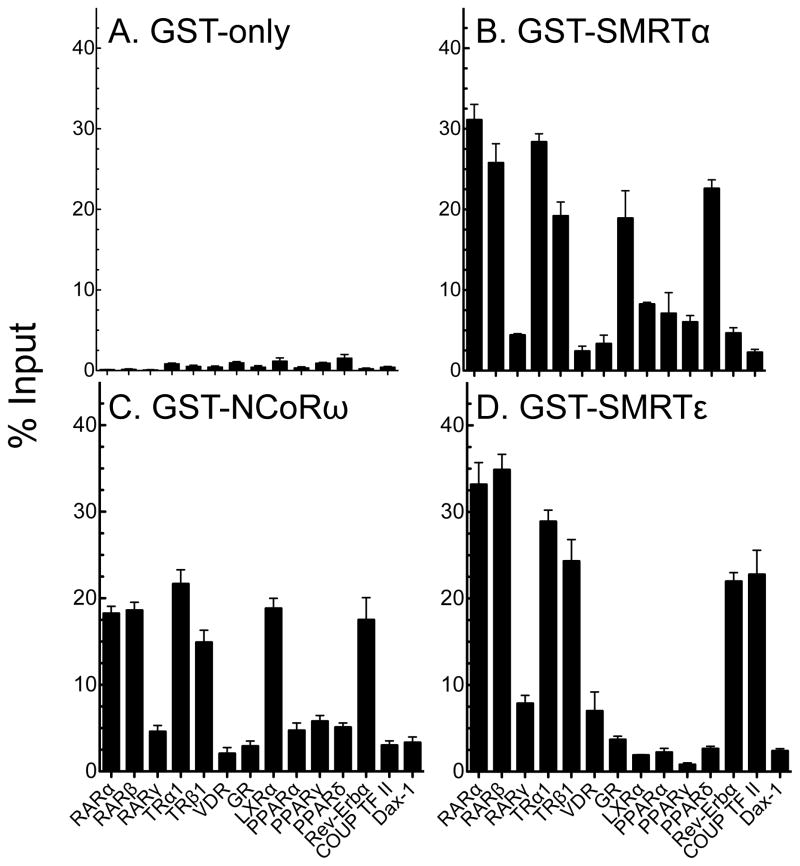

We next surveyed the ability of SMRTε to bind to a variety of nuclear receptors by a GST pulldown protocol. GST-SMRTε fusion constructs were synthesized in a recombinant baculovirus system, purified by binding to glutathione-agarose, and then tested for the ability to bind to a series of radiolabeled nuclear receptors. Equivalent GST-SMRTα and GST-NCoRω fusions, representing the corepressor variant prototypes first published and/or most widely studied (Horlein et al., 1995, Chen and Evans, 1995, Ordentlich et al., 1999), were tested in parallel. Background binding to a GST-only negative control was uniformly very low for all nuclear receptors tested (Fig. 2A, with additional statistical analysis in Supplemental Table 1). The GST-SMRTα construct displayed a relatively broad specificity, binding strongly to RARα, RARβ, TRα1, TRβ1, LXRα, and Rev-Erbα, moderately to PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ, and weakly to RARγ and COUP-TFII (Fig. 2B). The GST-NCoRω construct displayed a specificity that largely paralleled the SMRTα specificity (Fig. 2C). The SMRTε construct, however, recognized a clearly distinct set of these receptors, retaining the ability of SMRTα to bind strongly to RARα, RARβ, TRα1, TRβ1, and Rev-Erbα, but losing the ability to bind to LXRα, PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ, while gaining an enhanced ability to bind COUP-TFII and (to a much lesser extent) RARγ and VDR (Fig. 2D). All three corepressor variants interacted only weakly with Dax-1 and GR (Fig. 2A–D).

Fig. 2.

SMRTε displays a distinct specificity for nuclear receptors compared to SMRT α or NCoRω. Proteins representing the (A) GST-only, (B) GST-SMRTα, (C) GST-NCoRω, or (D) GST-SMRTε constructs described in Materials and Methods were expressed in Sf9 cells, immobilized on glutathione-agarose beads and incubated with the radiolabeled nuclear receptors indicated below. The immobilized GST-constructs were then washed, and the nuclear receptor remaining bound to each construct was eluted and quantified (input=100%). The mean and standard error from at least three independent experiments are shown.

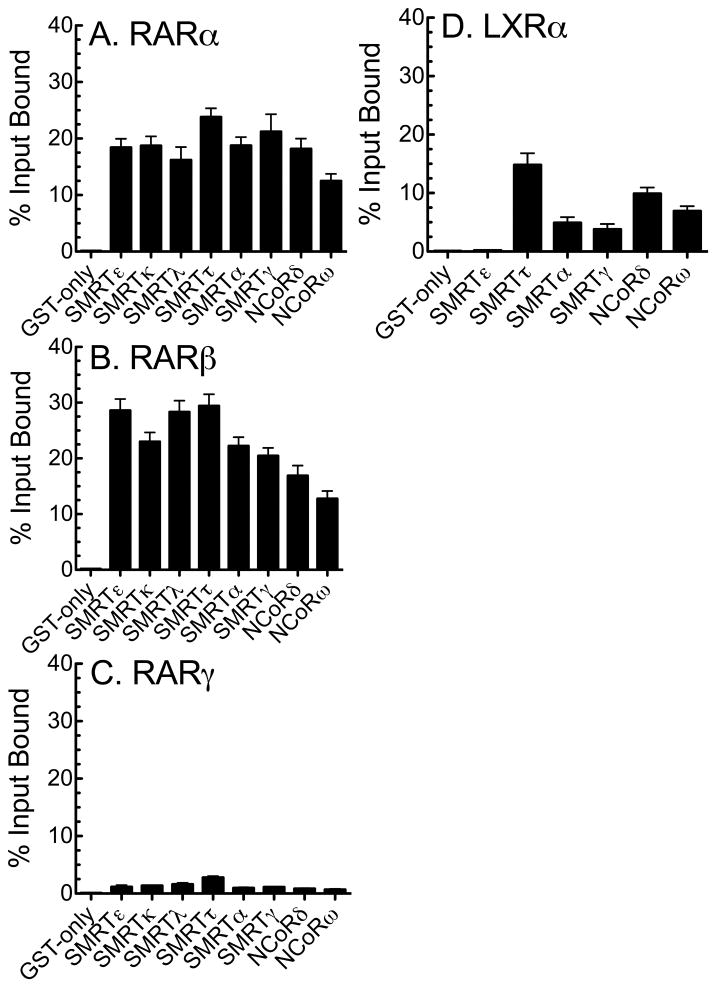

We conclude that SMRTε recognizes a distinct subset of nuclear receptors compared to SMRTα or NCoRω. Reciprocally, certain nuclear receptors tested appeared to be relatively specific for a given corepressor variant in the GST-pulldown assay, whereas others were broader in their binding abilities. We therefore expanded this comparison for RARα, RARβ, RARγ, and LXRα to additional corepressor splice variants. Notably RARα and RARβ had a broad specificity and interacted strongly with all the corepressor variants tested, RARγ reacted weakly with all, whereas LXRα displayed a more selective specificity, interacting most strongly with SMRTτ and NCoRδ, more weakly with SMRTα, SMRTγ, NCoRω, and (as noted previously) not detectably with SMRTε (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

RARs and LXR bind to differing sets of corepressor splice variants. The ability of radiolabeled (A) RARα, (B) RARβ, (C) RARγ, and (D) LXRα to bind to the GST-corepressor splice variants (GST-CoR) indicated below each panel was tested using the protocol in Fig. 2.

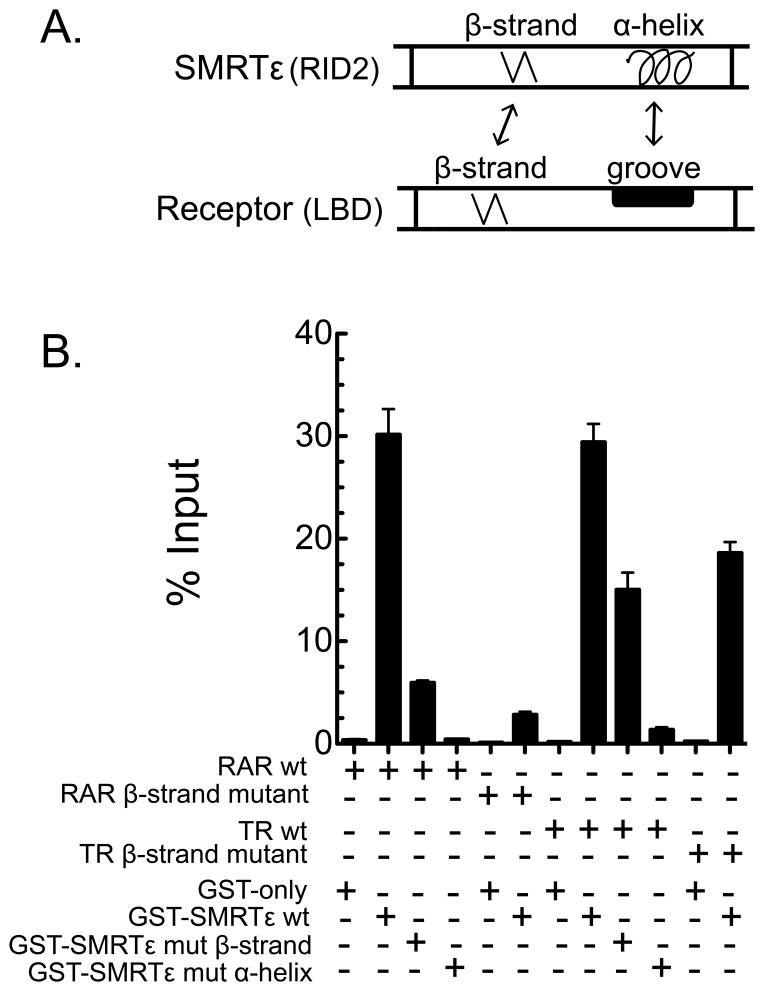

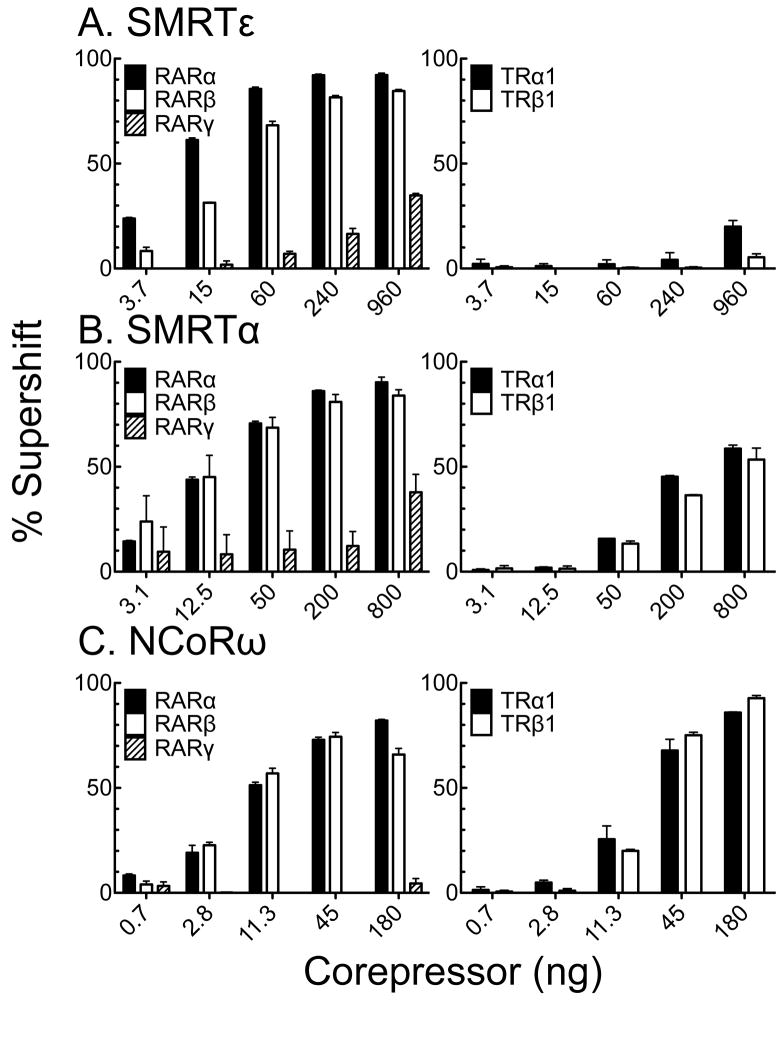

3.3. A β-strand motif in SMRTε helps define acceptable nuclear receptor partnerships

The nuclear receptors that bind to SMRTε in our GST-pulldown assay must do so by interacting with RID2 (all other known RIDs are absent from this construct). RID2 contains a well-characterized α-helical “CoRNR box motif” that can interact with a matching hydrophobic groove present on the surface of many nuclear receptors (Fig. 4). Discovered only recently, however, is a β-strand region present in RID2 that can interact with a complementary β-strand motif in the RARs and Rev-Erbs (Fig. 4A); this anti-parallel β-strand/β-strand interaction helps stabilize corepressor recruitment by these two receptors ((le Maire et al., Phelan et al.). These prior studies did not perform a broad survey of corepressor variants/receptors. Therefore, we examined if the same phenomenon contributed to the interaction of the SMRTε variant with several of the receptors tested here. Disrupting either the β-strand motif of the corepressor, or the β-strand motif of RARα by use of appropriate amino acid substitutions severely inhibited the interaction of SMRTε with RARα (Fig. 4B). Similarly, disruption of the α-helical CoRNR box motif in SMRTε also destabilized RARα binding (Fig. 4B). These results are consistent with the proposal that both the β-strand/β-strand and α-helical/hydrophobic groove interactions are required for high affinity RARα binding by the SMRTε RID2.

Fig. 4.

The ability of SMRTε to bind to either RARα or to TRα1 is enhanced by β-strand/β-strand interaction motifs. (A) The RID2 domain of SMRTε is depicted schematically on top; indicated are the β-strand and α-helical domains, and the mutations used in panel B. A corresponding schematic of the β-strand and hydrophobic groove regions within the ligand binding domain (LBD) of RARα and TRα1, is depicted below; in the native receptor the hydrophobic grove is assembled from portions of helix 3, 4, and 5 that are brought together by protein folding. (B) Mutations that disrupt either the α-helical or β-strand motifs destabilize the interaction of SMRTε with RARα and TRα1. Four GST-constructs were employed: GST-only, GST-SMRTε wild-type, GST-SMRTε bearing a β strand mutation (V2141P), or a GST-SMRTε bearing an α-helix CoRNR box mutation (an II to AA substitution within amino acids 2092–2096). These constructs were tested for the ability to bind to RARα wild-type, RARα bearing a β-strand mutation (I396E), TRα1 wild-type, or TRα1 bearing a presumptive β-strand mutation (L386E) by the protocol in Figure 2. The interactions of the wt receptors with wt SMRTε, versus the wt receptors with the β-strand or α-helix SMRTε mutants, were all statistically different with a p value < 0.001. Similarly, the interactions of the wt SMRTε with the wt receptors, versus the β-strand mutant receptors, were all statistically different with a p value <0.001.

Unexpectedly, the ability of SMRTε to bind to TRα was also decreased by mutagenesis of the β-strand motif in SMRTε, although to a lesser extent than seen for RARα (Fig. 4B). The same was true of a mutation in the region of TRα1 that corresponds to the β-strand region of RARα (Fig. 4B). In contrast, disruption of the α-helical CoRNR box motif in the RID2 of the SMRTε construct completely abrogated TRα binding (Fig. 4B). These experiments suggest that nuclear receptors, such as TRα1, previously thought to dock to SMRT exclusively through α-helical/hydrophobic groove contacts, are likely to make additional, β-strand/β-strand contacts that further stabilize their binding to RID2.

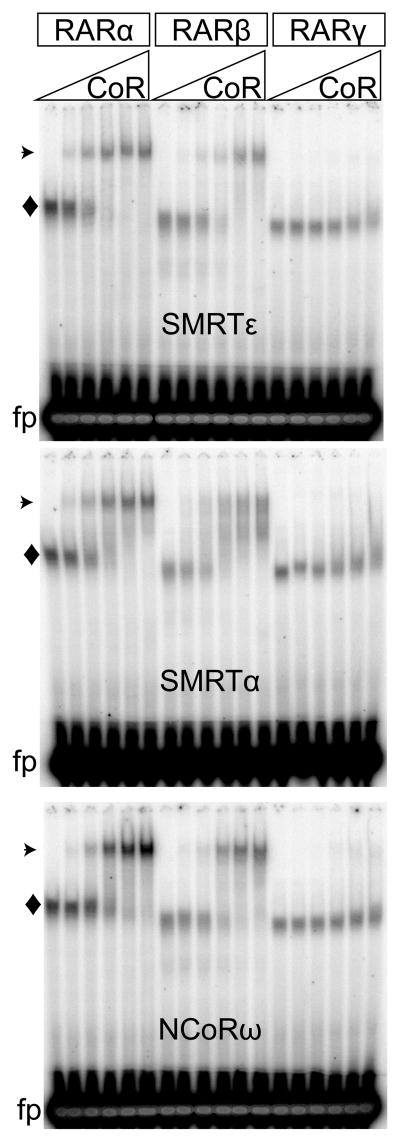

3.4. Binding to DNA narrows further the nuclear partner specificity of SMRTε

DNA binding restricts the ability of many nuclear receptors to recruit SMRT and NCoR, at least in part due to differences in the corepressor contacts made with the receptor dimers that form on DNA versus receptor monomers in solution. PPARγ, for example, binds NCoRω in solution, but not when bound to DNA in the form of a receptor dimer (Zamir et al., 1997b). TRs interact with SMRTα and NCoRω both in solution and when bound to DNA as TR homodimers, but not when bound to the same DNA sequence as TR/RXR heterodimers (Cohen et al., 1998, Cohen et al., 2000, Machado et al., 2009, Yoh and Privalsky, 2001). We therefore used an electrophoretic mobility shift/supershift assay (EMSA) to test whether the nuclear receptors that bound SMRTε in our prior GST-pulldown protocol retained that ability when bound to DNA. We previously have shown that RXR heterodimer formation strongly interferes with corepressor recruitment (Mengeling et al., 2011, Yoh et al., 2001), so we focused on receptor homodimers in these assays.

RARα readily bound to a cognate DR5 DNA response element (a direct-repeat of AGGTCA with a 5 base spacer) as a receptor homodimer (Fig. 5); the identity of these complexes has been extensively characterized (Phan et al. 2010). These RARα homodimer/DNA complexes were efficiently bound (supershifted) by all three corepressors tested: SMRTε, SMRTα, and NCoRω (Fig. 5). RARβ homodimers, assembled on the same DR5 element, were also efficiently supershifted by all three corepressors tested, whereas RARγ homodimers on the DR5 element were supershifted by these corepressors very weakly or not at all (Fig. 5). RARs also bind to DR2 DNA response elements (Claessens and Gewirth, 2004), and the RAR homodimers that formed on a DR2 element were supershifted by SMRTε to a similar extent as were the RAR homodimers that formed on a DR5 element (quantified in Supplemental Fig. 2).

Fig. 5.

SMRTε binds strongly to RARα and RARβ homodimers assembled on a cognate DNA response element, despite the single RID domain in this corepressor variant. Recombinant RARα, β, and γ proteins were incubated with a radiolabeled DNA probe containing a cognate DR5 response element, either alone (first lane of each panel), or together with increasing amounts of the corepressor constructs indicated. The resulting free probes (fp), RAR/DNA complexes (◆), and supershifted corepressor/RAR/DNA complexes (⊙) were resolved by native gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimaging. Representative phosphoimager scans are shown.

Although TRα1, TRβ1, Rev-Erbα and COUP-TFII also formed receptor homodimers on their cognate DNA response elements, these receptor/DNA complexes were not significantly supershifted by SMRTε. Nonetheless, TRα1, TRβ1 were both strongly supershifted by SMRTα and by NCoRω, and consistent with prior studies, Rev-Erbα was supershifted by NCoRω, but not by SMRTα (Fig. 6A). No corepressor binding was detected for COUP-TFII by EMSA supershift (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

SMRTε fails to bind to TRα1, TRβ1, Rev-Erbα, or COUP-TFII homodimers assembled on cognate DNA response elements. Recombinant TRα1, TRβ1, Rev-Erbα, or COUP-TFII proteins were incubated with radiolabeled DNA probes containing the cognate response elements (an F2-lysozyme element for the TRs, a DR2 for Rev-Erbα, and a DR4 for COUP-TFII), either alone (first lane of each panel), or together with increasing amounts of the corepressor constructs indicated. The resulting receptor/DNA complexes, either receptor monomers (●) or dimers (◆), and supershifted corepressor/receptor/DNA complexes (⊙) were resolved by native gel electrophoresis and visualized by phosphorimaging. The positions of free probe were deleted from these figures to save space. Representative experiments are shown.

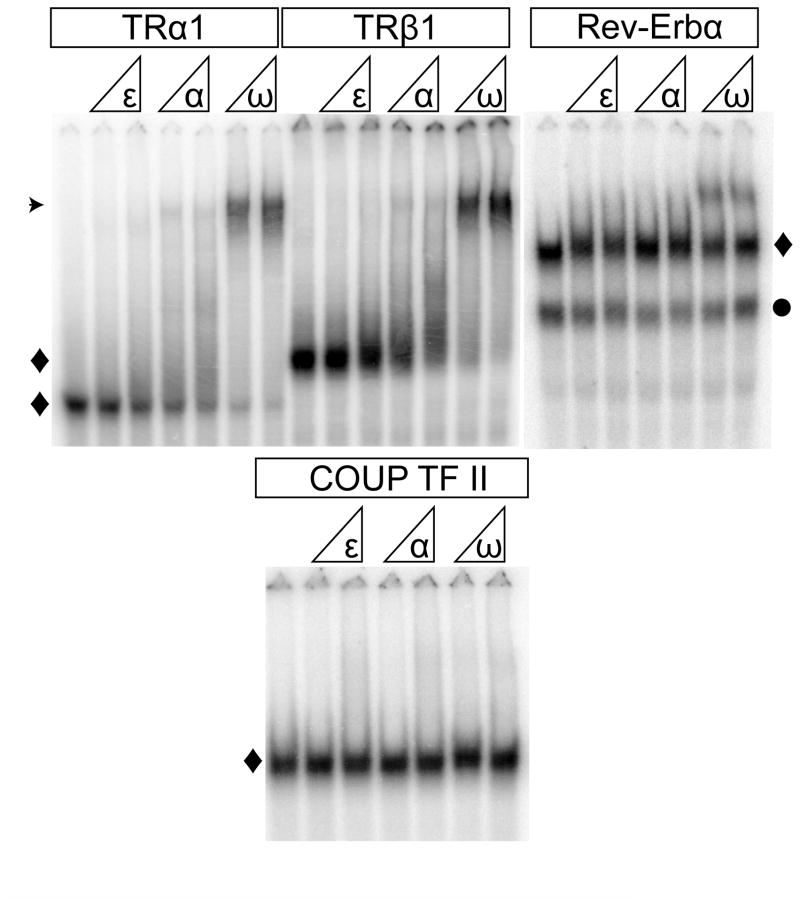

We quantified the results of multiple RAR and TR EMSA supershifts (Fig. 7). RARα bound most efficiently to SMRTε, and SMRTα, and more weakly to NCoRω by this method (Fig. 7A–C). RARβ bound slightly less efficiently to SMRTε than did RARα (most observable at lower SMRTε concentrations) but was near equal to RARα in binding to SMRTα and NCoRω (Fig. 7A–C). RARγ bound weakly to SMRTε and SMRTα, but not to NCoRω (Fig. 7A–C). TRα1 and TRβ1 displayed virtually no ability to bind SMRTε, but bound to both SMRTα and NCoRω, with the latter significantly stronger than the former (Fig. 7D–F); the overall affinities of TRα1 and TRβ1 for NCoRω and SMRTα were also somewhat lower than observed for RARα and RARβ. We conclude that SMRTε displays high specificity for RARα and, to a slightly lesser extent, RARβ, when assayed in the context of a cognate DNA response element, and binds poorly or not at all to the other nuclear receptors tested under the same conditions.

Fig. 7.

Quantification of the EMSA supershift experiments for RARs and TRs. Multiple EMSA supershift experiments, performed as in Fig. 5 and 6, were quantified using the nuclear receptors indicated and (A) SMRTε, (B) SMRTα, or (C) NcoRω. The mean and standard error from three (RARs) or two (TRs) experiments are shown.

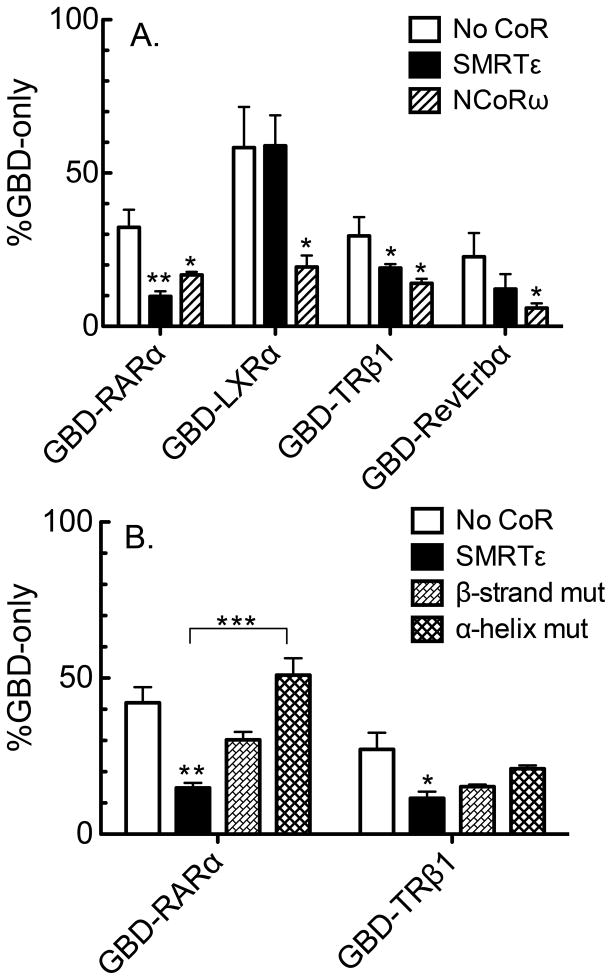

3.5. SMRTε can help enhance repression by RARα in cells

We next examined if the ability of SMRTε to bind RARα in vitro was reflected in its ability to participate in RARα-mediated transcriptional repression ex vivo. We introduced a Gal17-mer-luciferase reporter into CV-1 cells together with a Gal4-DNA binding domain GBD-RARα construct, a GBD-LXRα construct, or a GBD-only construct. In the absence of ligand, both the GBD-RARα and the GBD-LXRα constructs repressed reporter gene expression compared to the empty GBD (Fig. 8A). Coexpression of either SMRTε or NCoRω in these cells resulted in more severe reporter gene repression by the GBD-RARα construct. In contrast, only NCoRω, and not SMRTε, enhanced repression by the GBD-LXRα construct. Consistent with our in vitro binding experiments, these experiments suggest that SMRTε can partner with RARα, but not LXRα, to mediate transcriptional repression in cells, whereas NCoRω can partner with a broader range of nuclear receptors, including both LXRα and RARα.

Fig. 8.

SMRTε can enhance repression by RARα and TRβ1. (A) An expression vector encoding a Gal4 DNA binding domain (GBD) only, a GBD-RARα(LBD) fusion, a GBD-LXRα(LBD) fusion, a GBD-TRβ1(LBD) fusion, or a GBD-Rev-Erbα(LBD) fuson was transfected into CV1 cells together with a GAL-17 mer luciferase reporter. Also included was an empty expression vector (no CoR), an expression vector for full-length SMRTε, or an expression vector for full length NCoRω, as indicated. After 48 hours the cells were harvested and luciferase activity was assayed. The luciferase activity, relative to that of the GAL4DBD alone (defined as 100%), is shown for each construct. The mean and standard error from four experiments are presented. (B) The same experiment as in panel B was repeated using GBD-RARα or GBD-TRβ1 with GST-SMRTε wild-type, GST-SMRTε bearing a β strand mutation (V2141P), or a GST-SMRTε bearing an α-helix CoRNR box mutation (an II to AA substitution within amino acids 2092–2096). (*) indicates a p value < 0.05; (**) indicates a p value < 0.01; (***) indicates a p value of < 0.005.

We expanded this assay to include GBD-TRβ1 and GBD-RevErbα constructs, representing nuclear receptors that interacted with SMRTε in our GST-pulldowns but not in the EMSA supershift protocol. The GBD-TRβ1 fusion repressed reporter gene expression in the absence of an ectopic corepressor construct, and this repression was more severe in the presence of either SMRTε or NCoRω. Repression by the GBD-RevErbα construct was also enhanced by expression of NCoRω and possibly by SMRTε (although the latter was not statistically significant). We note that our reporter assay utilized GAL4 binding sites whereas our EMSA-supershifts employed native receptors and consensus response elements; taken together with our GST-pulldown data, these results indicate that the ability of the different corepressor splice forms to physically and functionally interact with specific nuclear receptors can depend on context.

Finally we examined if the β-strand/β-strand interaction necessary for efficient interaction of the RARs and TRs with SMRTε in vitro was also required for SMRTε function in these reporter gene assays. Notably, amino acid substitutions designed to disrupt either the β-strand or the CoRNR box α-helical regions in SMRTε impaired the ability of this corepressor variant to enhance repression by either GBD-RARα or GBD-TRβ1 in our transfection assay (Figure 8B). Our results are consistent with both of these motifs contributing to the ability of SMRTε to partner functionally, as well as physically, with these two nuclear receptors.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Alternative mRNA splicing creates corepressor variants selective for specific nuclear receptors

We report here a characterization of SMRTε, an unusual, alternatively-spliced form of the SMRT corepressor that possesses only a single RID domain (RID2) within its C-terminal region (Short et al., 2005). The alternative splice event that generates SMRTε is conserved in both humans and mice and is observed in many mammalian tissues and established cell lines ((Faist et al., 2009, Goodson et al., 2005a, Malartre et al., 2004, Short et al., 2005) and MLG unpublished observations). Interestingly, although SMRT itself is found throughout the vertebrate lineage, the SMRTε splice product can not be detected in Xenopus or Danio by RT-PCR or by EST database inspection, indicating that SMRTε is a relatively recent evolutionary development ((Faist et al., 2009, Goodson et al., 2005a, Malartre et al., 2004, Short et al., 2005) and MLG unpublished observations). Consistent with this interpretation, although alternative mRNA splicing at the NCoR locus often parallels that at the SMRT locus, an ε-like form of NCoR has not been identified. Instead all known NCoR splice variants encode both RID1 and RID2. Taken as a whole, these observations suggest that the alternative splicing event that generates SMRTε arose after the evolutionary duplication and divergence that produced the distinct SMRT and NCoR loci, and after the divergence of mammals from teleost and amphibian lineages.

In an immobilized protein-protein interaction assay, SMRTε interacts strongly with RARα, RARβ, TRα1, TRβ1, Rev-Erbα, and COUP-TFII, but binds weakly, or not at all, to RARγ, LXRα, Dax1, GR, PPARα, PPARγ, and PPARδ. In contrast, the SMRTα splice variant, which encodes both RID2 and RID1, also binds PPARα, PPARγ, PPARδ, and LXRα, but fails to bind COUP-TFII. NCoRω, which encodes all three RIDs, largely parallels SMRTα in the same assay. It is interesting to note that the insertion of a RID through alternative splicing can either increase or decrease the interaction of corepressor with a given nuclear receptor; for example, the presence of RID3 in SMRTα increases its binding to LXRα, yet decreases its binding to COUP-TFII. It is possible that the presence of a “wrong” RID in a corepressor splice variant can interfere allosterically, or otherwise, with the ability of the “correct” RID to interact productively with a given nuclear receptor partner.

DNA binding by nuclear receptors further restricts their ability to recruit corepresssors. SMRTε, when tested on receptor homodimers assembled on their cognate DNA response elements, became specific for RARα and (to a lesser extent) RARβ, and lost the ability to interact efficiently with any of the other nuclear receptors tested. Unlike SMRTε, the SMRTα and NCoRω variants remained able to recognize a broad spectrum of DNA-bound nuclear receptors, with RARα, RARβ, TRα1, and TRβ1 recognized by both SMRTα and NCoRω, with RARγ recognized by SMRTα, and with Rev-Erbα recognized by NCoRω. These results are consistent with a prior EMSA supershift study that demonstrated the SMRTε variant can bind to RARα, but not to PPARγ (Faist et al., 2009), although our results and those of the previous study differ in a number of details relating to the relative ability of different receptors to interact with different SMRT variants. Notably the prior study focused on RAR/RXR heterodimers, which bind to corepressors much more weakly than do the RAR (and TR) homodimers analyzed in our own experiments (Cohen et al., 1998, Cohen et al., 2000, Ghosh et al., 2002, Mengeling et al., 2011, Yoh and Privalsky, 2001, Zubkova and Subauste, 2004). Although we favor the concept that homodimers of TRs and of RARs are important mediators of repression in vivo (e.g. (Machado et al., 2009)), heterodimers of these receptors clearly contribute to transcriptional regulation, and it is plausible that these heterodimers contribute to transcriptional repression in certain contexts.

Consistent with our GST-pulldown and EMSA in vitro receptor interaction assays, SMRTε enhanced repression by a GBD-RARα construct, but not by a GBD-LXRα construct in transfected cells, whereas NCoRω enhanced repression by both nuclear receptors. TRβ1 and Rev-Erbα interact with SMRTε by GST-pulldown, but fail to do so by EMSA supershift; intriguingly, repression by GBD-TRβ1 and by GBD-Rev-Erbα also appeared to be enhanced by co-expression of SMRTε or NCoRω (although the effect of SMRTε on GBD-Rev-Erbα did not achieve statistical significance). It appears likely that the nature of receptor/DNA interaction interface, the sequence of the DNA binding site itself, and/or the presence of bridging proteins and other transcription factors bound to a particular target gene in cells can further influence the corepressor interactions observed using consensus response elements and purified proteins in vitro. It is therefore likely that both the GST-pulldown and EMSA supershift methodologies reveal biologically relevant, if distinct, features of the corepressor/receptor interaction. These issues are described in more detail in Section 4.3. Although it would be informative to examine SMRTε occupancy on different target genes using chromatin immunoprecipitation methods, there are significant technical limitations to such a strategy, including the difficulty of obtaining specific antisera to a protein that can be distinguished from other SMRT splice variants only by the absence of certain epitopes.

Taken as a whole, our results suggest that alternative mRNA splicing can tailor corepressor specificity to a particular subset of nuclear receptor partners, and this tailoring can impact repression more than does the genetic locus of origin. SMRTγ and NCoRω, for example, despite being generated from different loci, possess similar arrangements of RIDs (Suppl. Fig 1), are enriched in mouse brain and testes, and target extensively overlapping nuclear receptor partners. In contrast, although originating from an identical locus, SMRTγ and SMRTε display very different RID organizations, tissue distributions, and nuclear receptor specificities (Goodson et al., 2005a, Malartre et al., 2004, Short et al., 2005). Many studies of SMRT and NCoR, performed before recognition of the extensive splicing at these loci, compared the properties of SMRTα to those of NCoRω. Current insight indicates a more apt comparison would be SMRTα to NCoRδ, or SMRTγ to NCoRω, and would likely reveal more similarities than previously recognized.

4.2. SMRTε requires a recently recognized β-strand motif to bind to its nuclear receptor partners

Each CoRNR box motif in the SMRT and NCoR corepressors can form an extended α-helix that can dock with a matching hydrophobic groove on the surface of an appropriate nuclear receptor partner. Differences in the amino acid sequence in the CoRNR boxes themselves, or in flanking regions, help determine which CoRNR box, and therefore which corepressor, can interact with a given nuclear receptor. It was recently discovered that a β-strand motif adjacent to the RID2 CoRNR box itself also contributes to corepressor docking by RARs and Rev-Erbα (le Maire et al., 2010, Phelan et al. 2010). A portion of helix 11 in these two receptors can assume a β-strand conformation that in turn interacts with the β-strand in the corepressor to further stabilize the complex. Our studies confirm that both the α-helix and β-strand motifs in the SMRTε RID2 domain contribute to the ability of this splice variant to tether RARs in the immobilized protein assay and to function with RARα to mediate repression in our reporter gene assay. Notably, the β-strand mutation in SMRTε also compromises the ability of TRα1 to interact with SMRTε, although not to the same extent as in RARα or the mutation in CoRNR box α-helix sequence; both the β-strand and CoRNR box α-helix contributed to the ability of SMRTε to enhance TR-mediated repression. We suggest that a wider variety of nuclear receptors than previously reported employ the β-strand surface in RID2 to stabilize their recruitment of corepressor, and that this mode of corepressor interaction plays a particularly important role in SMRTε binding due to the absence of RID1 and RID3 from this splice variant.

4.3. Nuclear receptor binding to DNA modulates the corepressor partnership

As noted, the panel of nuclear receptors recognized by SMRTε was further restricted when tested by EMSA using cognate DNA response elements, with RARα and RARβ the only permissive partners detected. This type of DNA-mediated restriction has been reported before for other nuclear receptors and for other corepressor splice variants (e.g. (Cohen et al., 1998, Cohen et al., 2000, Ghosh et al., 2002, Machado et al., 2009, Yoh and Privalsky, 2001, Zamir et al., 1997b, Zhang et al., 1999)), yet the molecular basis remains incompletely understood. As observed here for TRα1 and TRβ1, the DNA-bound receptor can lose the ability to bind to SMRTε, yet retain the ability to bind to other SMRT or NCoR splice variants. This suggests that DNA binding can impair the ability of certain nuclear receptors to bind to RID2, but remain permissive for receptor binding to RID1 or RID3. It has been proposed that each nuclear receptor dimer, when bound to DNA, recruits corepressors by contacting two RID domains simultaneously on a single SMRT or NCoR molecule (Cohen et al., 1998, Downes et al., 1996, Ghosh et al., 2002, Hu et al., 2001, Machado et al., 2009, Makowski et al., 2003, Zamir et al., 1997b). In this model, the spacing and orientation of the RIDs in a given corepressor variant must match the topology of the corresponding corepressor binding surfaces on the receptor dimer. Although this model may explain why SMRTε, restricted to a single RID2 domain, fails to bind TRs, Rev-Erbα, and COUP-TFII in the EMSA supershift, it does not account for why SMRTε retains the ability to bind to RARα and β under the same circumstances.

We considered other possibilities. Perhaps the RARα dimer recruits one molecule of SMRTα, but two molecules of SMRTε? Arguing against this concept, the mobilities of the SMRTε/RARα and SMRTα/RARα complexes were the same in our EMSA supershifts, suggesting the stoichiometry was the same for both splice variants. Alternatively, RID-like motifs have been mapped to the SMRT and NCoR N-termini (Varlakhanova et al., 2010, Wu et al., 2006, Zhang et al., 2009); these “nRIDs” hypothetically could substitute for the RID1 absent from the SMRTε C-terminus. However, the SMRT nRID exhibits little or no ability to interact with RARs (Varlakhanova et al., 2010), and RARα and RARβ were both bound efficiently in our EMSA supershifts by SMRTε constructs lacking nRIDs. Our results therefore indicate that one RID per corepressor molecule is indeed sufficient for efficient recruitment by certain nuclear receptor dimers when bound to their response elements. We suggest that receptor binding to a given DNA response element alters both the conformation of the individual receptors and the overall structure of the receptor dimer, and that these DNA-mediated changes do not impose a universal requirement for two RIDs per corepressor, but rather work as a whole to select for specific RID sequences and topologies among the different corepressor variants available. This is consistent with the ability of a given nuclear receptor to recognize RIDs separated by a variety of different spacings (Astapova et al., 2009).

4.4. Potential impact of other alternative splicing events on SMRT and NCoR function

In addition to SMRTε, other alternative splicing events in SMRT and NCoR also influence nuclear receptor selectivity. For example, SMRTτ is a 44b+ splice variant that deletes sequences C-terminal to the RID1 CoRNR box without affecting the CoRNR box itself; SMRTτ exhibits a 5 to 10-fold decreased affinity for TRα1 and TRβ1, yet a near equal affinity for RARs, compared to SMRTα (Goodson et al., 2005b). NCoRω, generated by an alternative exon 37b+ splice that introduces a third RID, displays a significantly increased affinity for TRs, but a reduced affinity for COUP-TFII and Rev-Erb, compared to NCORδ (which contains only RID2 and RID1) (Bailey et al., 1997, Cohen et al., 2001, Downes et al., 1996, Makowski et al., 2003, Webb et al., 2000).

Alternative splicing events operating at multiple sites can assemble yet-additional corepressor variants. For example, combination of the 37b+ SMRT splice with the 44- SMRT splice encodes a variant (denoted SMRTλ in our nomenclature; Suppl. Fig. 1) that contains RID3 and RID2, but not RID1 (Faist et al., 2009). A SMRTλ construct binds RARα both in our GST-pulldown experiments and in a previously reported EMSA experiment (wherein it was reported to bind more weakly than did the single RID SMRTε) (Faist et al., 2009). With the exception of brain and testes, however, the 37b+ splicing event is infrequent and displays an inverse tissue distribution to that of the 44- splice; as a consequence, we estimate that SMRTλ is very rare (present at only 10% to 20% of the levels of SMRTε) in the murine tissues we’ve examined.

There is no evidence to date for naturally-occurring splice forms of SMRT or NCoR that lack all RIDs, or that contain RID1 and/or RID3, yet lack the central RID2. Artificial SMRT mutants lacking RID2, or lacking both RID2 and RID1, lose the ability to interact with a broad sweep of nuclear receptors in vitro, and they display a series of developmental, endocrine, and metabolic defects, including aberrant thyroid hormone homeostasis and enhanced adipogenesis (Astapova et al., 2008, Fang et al., Nofsinger et al., 2008, Reilly et al.). It is possible that RID2, although not absolutely essential for mouse viability, is required for partnering with so many different nuclear receptors that its removal by alternative splicing would be strongly counter-selected during evolution.

In summary, alternative mRNA splicing generates a diverse series of corepressor variants, such as SMRTε, that display different affinities for different nuclear receptor partners. Different splice variants also respond divergently to the kinase signals that regulate their activity (Jonas et al., 2007). Given that different tissues preferentially express different corepressor variants, we propose that organisms utilize alternative corepressor splicing to establish cell-type specific transcriptional repression programs, thereby permitting a given nuclear receptor to exert cell- and tissue-specific transcriptional regulation.

Supplementary Material

The different corepressor variants utilized in Fig. 3 are indicated schematically. The domains are as described in Fig. 1A

SMRTε binds strongly to RARα and RARβ homodimers assembled on a DR2 DNA response element. Multiple EMSA supershift experiments, performed as in Fig. 5 and 6, were quantified using the RARs indicated and SMRTε on either a cognate DR2 or DR5 element.

HIGHLIGHTS.

SMRTε is an alternatively-spliced form of corepressor.

SMRTε expression differs in different cell types.

SMRTε displays a restricted specificity for a subset of nuclear receptor partners.

SMRTε interacts with nuclear receptors by a mix of α-helical and β-strand surfaces.

SMRTε is highly specific for RARs when bound to their cognate DNA response elements.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Liming Liu for superb technical assistance, and Mehgan D. Rosen for creating the SMRTε, RARα, and TRα interaction motif mutants. This work was supported by Public Health Service/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases award RO1DK53528.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Brenda J. Mengeling, Email: mengeling@ucdavis.edu.

Michael L. Goodson, Email: mlgoodson@ucdavis.edu.

William Bourguet, Email: William.Bourguet@cbs.cnrs.fr.

Martin L. Privalsky, Email: mlprivalsky@ucdavis.edu.

REFERENCES CITED

- Astapova I, Dordek MF, Hollenberg AN. The thyroid hormone receptor recruits NCoR via widely spaced receptor-interacting domains. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2009;307:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astapova I, Lee LJ, Morales C, Tauber S, Bilban M, Hollenberg AN. The nuclear corepressor, NCoR, regulates thyroid hormone action in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19544–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804604105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey PJ, Dowhan DH, Franke K, Burke LJ, Downes M, Muscat GE. Transcriptional repression by COUP-TF II is dependent on the C-terminal domain and involves the N-CoR variant, RIP13delta1. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;63:165–74. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G, Cooney A, Giguere V, Ingraham H, Lazar M, Muscat G, Perlmann T, Renaud JP, Schwabe J, Sladek F, Tsai MJ, Laudet V. International Union of Pharmacology. LXVI. Orphan nuclear receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:798–836. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Brunet FG, Escriva H, Parmentier G, Laudet V, Robinson-Rechavi M. Evolutionary genomics of nuclear receptors: from twenty-five ancestral genes to derived endocrine systems. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:1923–37. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand S, Thisse B, Tavares R, Sachs L, Chaumot A, Bardet PL, Escriva H, Duffraisse M, Marchand O, Safi R, Thisse C, Laudet V. Unexpected novel relational links uncovered by extensive developmental profiling of nuclear receptor expression. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buranapramest M, Chakravarti D. Chromatin remodeling and nuclear receptor signaling. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2009;87:193–234. doi: 10.1016/S1877-1173(09)87006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke LJ, Downes M, Laudet V, Muscat GE. Identification and characterization of a novel corepressor interaction region in RVR and Rev-erbA alpha. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:248–62. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.2.0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JD, Evans RM. A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995;377:454–7. doi: 10.1038/377454a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens F, Gewirth DT. DNA recognition by nuclear receptors. Essays Biochem. 2004;40:59–72. doi: 10.1042/bse0400059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RN, Brzostek S, Kim B, Chorev M, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN. The specificity of interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and corepressors is mediated by distinct amino acid sequences within the interacting domains. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15:1049–61. doi: 10.1210/mend.15.7.0669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RN, Putney A, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN. The nuclear corepressors recognize distinct nuclear receptor complexes. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:900–14. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.6.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RN, Wondisford FE, Hollenberg AN. Two separate NCoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) interaction domains mediate corepressor action on thyroid hormone response elements. Mol Endocrinol. 1998;12:1567–81. doi: 10.1210/mend.12.10.0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downes M, Burke LJ, Bailey PJ, Muscat GE. Two receptor interaction domains in the corepressor, N-CoR/RIP13, are required for an efficient interaction with Rev-erbA alpha and RVR: physical association is dependent on the E region of the orphan receptors. Nucleic Acids Research. 1996;24:4379–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faist F, Short S, Kneale GG, Sharpe CR. Alternative splicing determines the interaction of SMRT isoforms with nuclear receptor-DNA complexes. Biosci Rep. 2009;29:143–9. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, Suh JM, Atkins AR, Hong SH, Leblanc M, Nofsinger RR, Yu RT, Downes M, Evans RM. Corepressor SMRT promotes oxidative phosphorylation in adipose tissue and protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108:3412–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017707108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant F, Baxter JD, Forrest D, Refetoff S, Samuels H, Scanlan TS, Vennstrom B, Samarut J. International Union of Pharmacology. LIX. The pharmacology and classification of the nuclear receptor superfamily: thyroid hormone receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:705–11. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh JC, Yang X, Zhang A, Lambert MH, Li H, Xu HE, Chen JD. Interactions that determine the assembly of a retinoid X receptor/corepressor complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5842–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092043399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Saijo K. Nuclear receptor transrepression pathways that regulate inflammation in macrophages and T cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;10:365–76. doi: 10.1038/nri2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson M, Jonas BA, Privalsky MA. Corepressors: custom tailoring and alterations while you wait. Nucl Recept Signal. 2005a;3:e003. doi: 10.1621/nrs.03003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson ML, Farboud B, Privalsky ML. An improved high throughput protein-protein interaction assay for nuclear hormone receptors. Nucl Recept Signal. 2007;5:e002. doi: 10.1621/nrs.05002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson ML, Jonas BA, Privalsky ML. Alternative mRNA splicing of SMRT creates functional diversity by generating corepressor isoforms with different affinities for different nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 2005b;280:7493–503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411514200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther MG, Lazar MA. Biochemical isolation and analysis of a nuclear receptor corepressor complex. Methods Enzymol. 2003;364:246–57. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)64014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hager GL. Understanding nuclear receptor function: from DNA to chromatin to the interphase nucleus. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2001;66:279–305. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)66032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson MC, Shen HC, Hollenberg AN, Balk SP. Structural basis for nuclear receptor corepressor recruitment by antagonist-liganded androgen receptor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:3187–94. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horlein AJ, Naar AM, Heinzel T, Torchia J, Gloss B, Kurokawa R, Ryan A, Kamei Y, Soderstrom M, Glass CK, Et Al. Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature. 1995;377:397–404. doi: 10.1038/377397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Li Y, Lazar MA. Determinants of CoRNR-dependent repression complex assembly on nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1747–58. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1747-1758.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas BA, Varlakhanova N, Hayakawa F, Goodson M, Privalsky ML. Response of SMRT (silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor) and N-CoR (nuclear receptor corepressor) corepressors to mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase cascades is determined by alternative mRNA splicing. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:1924–39. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones PL, Shi YB. N-CoR-HDAC corepressor complexes: roles in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2003;274:237–68. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-55747-7_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar MA. Nuclear receptor corepressors. Nucl Recept Signal. 2003;1:e001. doi: 10.1621/nrs.01001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Maire A, Teyssier C, Erb C, Grimaldi M, Alvarez S, De Lera AR, Balaguer P, Gronemeyer H, Royer CA, Germain P, Bourguet W. A unique secondary-structure switch controls constitutive gene repression by retinoic acid receptor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 17:801–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Leo C, Schroen DJ, Chen JD. Characterization of receptor interaction and transcriptional repression by the corepressor SMRT. Molecular Endocrinology. 1997;11:2025–37. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.13.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JW, Wang J, Wang JX, Nawaz Z, Liu JM, Qin J, Wong JM. Both corepressor proteins SMRT and N-CoR exist in large protein complexes containing HDAC3. EMBO J. 2000;19:4342–4350. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.16.4342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonard DM, O’malley BW. Nuclear receptor coregulators: judges, juries, and executioners of cellular regulation. Mol Cell. 2007;27:691–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado DS, Sabet A, Santiago LA, Sidhaye AR, Chiamolera MI, Ortiga-Carvalho TM, Wondisford FE. A thyroid hormone receptor mutation that dissociates thyroid hormone regulation of gene expression in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9441–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903227106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makowski A, Brzostek S, Cohen RN, Hollenberg AN. Determination of nuclear receptor corepressor interactions with the thyroid hormone receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:273–86. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malartre M, Short S, Sharpe C. Alternative splicing generates multiple SMRT transcripts encoding conserved repressor domains linked to variable transcription factor interaction domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:4676–86. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marimuthu A, Feng W, Tagami T, Nguyen H, Jameson JL, Fletterick RJ, Baxter JD, West BL. TR surfaces and conformations required to bind nuclear receptor corepressor. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:271–86. doi: 10.1210/mend.16.2.0777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcewan IJ. Nuclear receptors: one big family. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;505:3–18. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-575-0_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengeling BJ, Pan F, Privalsky ML. Novel mode of deoxyribonucleic acid recognition by thyroid hormone receptors: thyroid hormone receptor beta-isoforms can bind as trimers to natural response elements comprised of reiterated half-sites. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19:35–51. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengeling BJ, Phan TQ, Goodson ML, Privalsky ML. PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha oncoproteins display an altered recruitment and release of specific corepressor variants. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:4236–4247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.200964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehren U, Eckey M, Baniahmad A. Gene repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Essays Biochem. 2004;40:89–104. doi: 10.1042/bse0400089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muscat GE, Burke LJ, Downes M. The corepressor N-CoR and its variants RIP13a and RIP13Delta1 directly interact with the basal transcription factors TFIIB, TAFII32 and TAFII70. Nucleic Acids Research. 1998;26:2899–907. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.12.2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy L, Kao HY, Chakravarti D, Lin RJ, Hassig CA, Ayer DE, Schreiber SL, Evans RM. Nuclear receptor repression mediated by a complex containing SMRT, mSin3A, and histone deacetylase. Cell. 1997;89:373–80. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofsinger RR, Li P, Hong SH, Jonker JW, Barish GD, Ying H, Cheng SY, Leblanc M, Xu W, Pei L, Kang YJ, Nelson M, Downes M, Yu RT, Olefsky JM, Lee CH, Evans RM. SMRT repression of nuclear receptors controls the adipogenic set point and metabolic homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20021–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811012105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordentlich P, Downes M, Evans RM. Corepressors and nuclear hormone receptor function. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;254:101–16. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-10595-5_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordentlich P, Downes M, Xie W, Genin A, Spinner NB, Evans RM. Unique forms of human and mouse nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2639–44. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Jepsen K, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Deconstructing repression: evolving models of co-repressor action. Nat Rev Genet. 11:109–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perissi V, Staszewski LM, Mcinerney EM, Kurokawa R, Krones A, Rose DW, Lambert MH, Milburn MV, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG. Molecular determinants of nuclear receptor-corepressor interaction. Genes Dev. 1999;13:3198–208. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.24.3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan TQ, Jow MM, Privalsky ML. DNA recognition by thyroid hormone and retinoic acid receptors: 3,4,5 rule modified. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;319:88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2009.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan CA, Gampe RT, Jr, Lambert MH, Parks DJ, Montana V, Bynum J, Broderick TM, Hu X, Williams SP, Nolte RT, Lazar MA. Structure of Rev-erbalpha bound to N-CoR reveals a unique mechanism of nuclear receptor-co-repressor interaction. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 17:808–14. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Privalsky ML. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu Rev Physiol. 2004;66:315–60. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.155556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly SM, Bhargava P, Liu S, Gangl MR, Gorgun C, Nofsinger RR, Evans RM, Qi L, Hu FB, Lee CH. Nuclear receptor corepressor SMRT regulates mitochondrial oxidative metabolism and mediates aging-related metabolic deterioration. Cell Metab. 12:643–53. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sande S, Privalsky ML. Identification of TRACs (T3 receptor-associating cofactors), a family of cofactors that associate with, and modulate the activity of, nuclear hormone receptors. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:813–25. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.7.8813722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savkur RS, Bramlett KS, Clawson D, Burris TP. Pharmacology of nuclear receptor-coregulator recognition. Vitam Horm. 2004;68:145–83. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(04)68005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol W, Mahon MJ, Lee YK, Moore DD. Two receptor interacting domains in the nuclear hormone receptor corepressor RIP13/N-CoR. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1646–55. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short S, Malartre M, Sharpe C. SMRT has tissue-specific isoform profiles that include a form containing one CoRNR box. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;334:845–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda J, Pei L, Evans RM. Nuclear receptors: decoding metabolic disease. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanya KJ, Kao HY. New insights into the functions and regulation of the transcriptional corepressors SMRT and N-CoR. Cell Div. 2009;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CC, Fondell JD. Nuclear receptor recruitment of histone-modifying enzymes to target gene promoters. Vitam Horm. 2004;68:93–122. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(04)68003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlakhanova N, Snyder C, Jose S, Hahm JB, Privalsky ML. Estrogen receptors recruit SMRT and N-CoR corepressors through newly recognized contacts between the corepressor N terminus and the receptor DNA binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:1434–45. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01002-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb P, Anderson CM, Valentine C, Nguyen P, Marimuthu A, West BL, Baxter JD, Kushner PJ. The nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR) contains three isoleucine motifs (I/LXXII) that serve as receptor interaction domains (IDs) Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1976–1985. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.12.0566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen YD, Perissi V, Staszewski LM, Yang WM, Krones A, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Seto E. The histone deacetylase-3 complex contains nuclear receptor corepressors. Proc Nal Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:7202–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong CW, Privalsky ML. Transcriptional silencing is defined by isoform- and heterodimer-specific interactions between nuclear hormone receptors and corepressors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5724–33. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.5724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Kawate H, Ohnaka K, Nawata H, Takayanagi R. Nuclear compartmentalization of N-CoR and its interactions with steroid receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6633–55. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01534-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu HE, Stanley TB, Montana VG, Lambert MH, Shearer BG, Cobb JE, Mckee DD, Galardi CM, Plunket KD, Nolte RT, Parks DJ, Moore JT, Kliewer SA, Willson TM, Stimmel JB. Structural basis for antagonist-mediated recruitment of nuclear co-repressors by PPARalpha. Nature. 2002;415:813–7. doi: 10.1038/415813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoh SM, Privalsky ML. Transcriptional repression by thyroid hormone receptors: a role for receptor homodimers in the recruitment of SMRT corepressor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16857–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HG, Chan DW, Huang ZQ, Li J, Fondell JD, Qin J, Wong J. Purification and functional characterization of the human N-CoR complex: the roles of HDAC3, TBL1 and TBLR1. EMBO J. 2003;22:1336–46. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You SH, Liao X, Weiss RE, Lazar MA. The interaction between nuclear receptor corepressor and histone deacetylase 3 regulates both positive and negative thyroid hormone action in vivo. Mol Endocrinol. 24:1359–67. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir I, Dawson J, Lavinsky RM, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG, Lazar MA. Cloning and characterization of a corepressor and potential component of the nuclear hormone receptor repression complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997a;94:14400–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamir I, Zhang J, Lazar MA. Stoichiometric and steric principles governing repression by nuclear hormone receptors. Genes Dev. 1997b;11:835–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Hu X, Lazar MA. A novel role for helix 12 of retinoid X receptor in regulating repression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6448–57. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang LJ, Liu X, Gafken PR, Kioussi C, Leid M. A chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor I (COUP-TFI) complex represses expression of the gene encoding tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 8 (TNFAIP8) J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6156–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807713200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubkova I, Subauste JS. V-erba homodimers mediate the potent dominant negative activity of v-erba on everted repeats. Mol Biol Rep. 2004;31:131–7. doi: 10.1023/b:mole.0000031412.25988.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The different corepressor variants utilized in Fig. 3 are indicated schematically. The domains are as described in Fig. 1A

SMRTε binds strongly to RARα and RARβ homodimers assembled on a DR2 DNA response element. Multiple EMSA supershift experiments, performed as in Fig. 5 and 6, were quantified using the RARs indicated and SMRTε on either a cognate DR2 or DR5 element.