Summary

Pattern recognition scavenger receptor SRA/CD204, primarily expressed on specialized antigen-presenting cells (APCs), including dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages, has been implicated in multiple physiological and pathological processes, including atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease, endotoxic shock, host defense and cancer development. SRA/CD204 was also recently shown to function as an attenuator of vaccine response and antitumor immunity. Here we for the first time report that SRA/CD204 knockout (SRA−/−) mice developed a more robust CD4+ T cell response than wild-type mice after ovalbumin immunization. Splenic DCs from the immunized SRA−/− mice were much more efficient than those from WT mice in stimulating naïve OT-II cells, indicating that the suppressive activity of SRA/CD204 is mediated by DCs. Strikingly, antigen-exposed SRA−/− DCs with or without lipopolysaccharide treatment exhibited increased T cell-stimulating activity in vitro, which was independent of the classical endocytic property of the SRA/CD204. Additionally, absence of SRA/CD204 resulted in significantly elevated IL12p35 expression in DCs upon CD40 ligation plus IFN-γ stimulation. Molecular studies reveal that SRA/CD204 inhibited the activation of STAT1, MAPK p38 and NF-κB signaling activation in DCs treated with anti-CD40 antibodies and IFN-γ. Furthermore, splenocytes from the generated SRA−/− OT-II mice showed heightened proliferation upon stimulation with OVA protein or MHC II-restricted OVA323-339 peptide compared with cells from the SRA+/+ OT-II mice. These results not only establish a new role of SRA/CD204 in limiting the intrinsic immunogenicity of APCs and CD4+ T cell activation, but also provide additional insights into the molecular mechanisms involved in the immune suppression by this molecule.

Keywords: dendritic cells, CD4 T cell, immunity, CD204

Introduction

Scavenger receptors (SRs) represent a large family of protein molecules with diverse structures and a broad ligand-binding specificity [1]. Scavenger receptor A (SRA), also termed CD204 or macrophage scavenger receptor (MSR), is the prototypic member of the family and was initially identified because of its ability to bind and internalize modified low-density lipoprotein [2]. A large body of information supports the role of SRA/CD204 in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis and host defense through pathogen recognition and clearance [3–5]. In addition, subsequent studies have also revealed other features of this multifunctional molecule. While SRA/CD204 displays a protective role in endotoxic shock [6], Alzheimer's disease [7], and hyperoxia-induced lung injury [8], it has been shown to contribute to the pathophysiology of cerebral ischemic injury [9]. Moreover, germline mutations and sequence variants of SRA/CD204 gene have been reported to play a role in the development of prostate cancer albeit with ethnic-specific differences in risk estimates [10, 11].

SRA/CD204 is expressed primarily on phagocytic cells or antigen presenting cells (APCs) involved in immune functions, such as dendritic cells (DCs) and macrophages. These specialized APCs use a repertoire of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), e.g., toll-like receptors (TLRs) and SRs, to constantly sample or sense their surroundings for the presence of stress or `danger' signals (e.g., foreign pathogens, tissue injury and pathology) [12]. Effective recognition of the ligands by PRRs and initiation of host immune responses involve coordinated signaling and endocytic pathways. These professional APCs, such as DCs, are also crucial in stimulating and instructing naïve T cells during the immune responses [13]. Emerging evidence suggests that PRRs, including TLRs [14], Fc receptors [15], DEC-205 (CD205) [16], DC-SIGN [17], mannose receptor [18], play important roles in regulating the functions of DCs and maintenance of immune homeostasis as well as host defense. Indeed, early studies suggested that chemical modification of antigens for targeting to SRs increases the immunogenicity of these antigens [19–21]. Several SRs, including SRA/CD204, have been reported to mediate uptake of stress proteins and their associated antigens [22–25]. However, the mechanisms of SRA/CD204 action in antigen presentation and adaptive immunity remain poorly defined.

Despite the implication of SRA/CD204 in ligand binding and internalization, we recently made an unexpected discovery showing that SRA/CD204 was capable of attenuating vaccine response and antitumor immunity [26]. That lack of SRA/CD204 markedly promoted vaccine-elicited tumor-protective immunity may be attributed to the enhanced DC functions and activation of cytotoxic CD8+ T lymphocytes [26–28]. Downregulation of the ability of DC to stimulate CD8+ T cells and tumor immunity by SRA/CD204 has been reported in the context of the cross-presentation of soluble antigens [27] as well as cell-associated antigen [28]. However, it is not clear whether the SRA/CD204 also influences DC-mediated activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell response.

Given that CD4+ T cells play critical roles in orchestrating the adaptive immune responses, we sought to determine the functional significance of SRA/CD204 in the stimulation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Our studies using various model systems demonstrate that absence of SRA/CD204 on DCs greatly enhances the activation of OVA-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro and in vivo. We also provide biochemical evidence showing that the SRA/CD204-mediated immune modulation may be attributed to its ability to downregulate the activation of Janus kinase 1 (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 and NF-κB signaling, which are critical for production of IL-12 by DCs in the presence of CD40 ligation and IFN-γ signal. Our findings support the notion that SRA/CD204 on APCs functions as an immunosuppressive molecule capable of restricting CD4+ T cell activation, and may serve as a basis for the rational design of novel strategies targeting SRA/CD204 to achieve improved immunotherapeutic efficacy against cancer and other diseases.

Materials and Methods

Mice and cell lines

Wild type (WT) C57BL/6 mice were obtained from National Cancer Institute (Bethesda, MD). SRA/CD204 knockout mice (SRA−/−) on C57BL/6 background that have been backcrossed for at least ten generations were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). OT-II mice carrying TCR transgene specific for chicken OVA323-339 peptide were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY). SRA−/− mice were crossbred with OT-II mice to generate SRA/CD204 deficient OT-II transgenic mice (SRA−/− OT-II). For screening transgenic mice, genomic DNA was isolated from tail biopsies and analyzed by PCR using the following primers: SRA/CD204 knockout (forward 1: 5-GAGGTTCCGCTACGACTCTG-3; forward 2: 5-CCGGACAAGTTTTTCATCGT-3; reverse: 5- TGGATGTGGAATGTGTGCGA G-3), OT-II transgene (forward: 5-GCTGCTGCACAGACCTACT-3; reverse: 5-CAGCTCACCTAACACGAGGA-3). All experiments and procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Virginia Commonwealth University.

Antibodies and reagents

Mouse monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) to CD4 (GK1.5), Foxp3 (MF-14), CD11c (HL3), CD80 (16-10A1), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), IL-4 (11B11), IL-17a (TC11-18H10.1), IL-10 (JES5-16E3), isotype control rat IgG2b (RTK4530) and IgG1 (RTK2071) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). SRA/CD204 polyclonal antibodies for immunoblotting and mAb (2F8) for FACS analysis were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) and AbD Serotec (Raleigh, NC), respectively. Endotoxin-free OVA was obtained from Profos AG (Regenburg, Germany). Monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) and LPS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). PAM3CSK4, poly(I:C), ssRNA40 and CpG1826 were purchased from Invivogen (San Diego, CA). CellTrace 5-(and 6-)carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) cell proliferation kit and DQ-OVA were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). MHC II-restricted OVA323-339 peptides were purchased from AnaSpec Inc. (Fremont, CA).

Adoptive T cell transfer and immunization

A total of 2 × 106 CFSE-labeled OT-II cells were transferred into recipient mice by tail vein injection. Next day, mice were immunized subcutaneously (s.c.) with OVA (50 μg)-MPL (10 μg). Spleen and lymph nodes were harvested at indicated time points. OT-II cell proliferation was analyzed using FACS based on the dilution of fluorescence intensity.

T cell assays

Mice were immunized with OVA-MPL s.c twice at weekly intervals. Seven days after second immunization, splenocytes or lymph node cells were prepared in single cell suspensions. For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were stimulated with OVA323-339 peptide (1 μg/ml) for 96 h. Brefeldin A (BFA) was added for the last 5 h of culture. After surface staining with FITC-CD4 mAb, cells were permeabilized and stained with PE labeled IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A or IL-10 mAb (BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

To determine antigen-specific cytokine producing T cells, splenocytes or lymph node cells were prepared from mice 1 week after booster immunization and subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot (ELISPOT) assays as previously described [27]. To determine the effect of SRA/CD204 on suppressive functions of regulatory T cells (Tregs), CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25− T cells were isolated using regulatory T cell isolation kit from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). CD4+CD25− cells were stimulated with OVA323-339 peptide or anti-CD3/CD28 mAb in the presence or absence of Treg cells. Proliferation of CD4+CD25− T cells was determined using 3H-thymidine (TdR) incorporation assays. Culture supernatant was analyzed for cytokine levels using ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA).

DC generation and isolation from mice

Bone marrow (BM)-DCs were generated by culture of mouse BM cells in the presence of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) as described previously [27]. To prepare splenic DCs, spleens were minced and digested in RPMI media containing collagenase D (1 mg/ml) and DNase I (100 ng/ml) for 90 minutes at 37°C. After filtration through a 70-μm sieve, CD11c+ DCs were isolated by positive selection with CD11c antibody (N418)-coated microbeads on magnetic-activated cell-sorting columns (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA).

Receptor-mediated endocytosis assays

DCs were incubated with DQ-OVA (10 μg/ml) at 4 °C for 30 min. Cells were washed to remove unbound proteins and continued to incubate for indicated times at 37 °C. Cells were harvested and subjected to immunoblotting or FACS analyses for the DQ-OVA protein levels and florescence intensity due to DQ-OVA degradation, respectively.

T cell stimulation in vitro

BM-DCs were pulsed with OVA, DQ-OVA or OVA323-339 at 37 °C for 3 h, and stimulated with or without PAM3CSK4 (5 μg/ml), poly (I:C) (25 μg/ml), LPS (500 ng/ml), ssRNA40 (5 μg/ml) or CpG1826 (5 μg/ml) for additional 2 h. After washes, DCs were incubated with 5×104 OT-II cells at different ratios as indicated for 72 h. T cell proliferation was measured using 3H-TdR uptake assays. For assays of OVA-specific proliferation of CD4+ T Cells from the SRA−/− OT-II mice, splenocytes were incubated in a 96-well flat bottom plate (2×105 cells/well) with OVA protein or OVA323-339 peptide without LPS stimulation.

Activation of DCs by anti-CD40 mAbs plus IFN-γ

WT and SRA−/− DCs (2×106 cells/well) were suspended in RPMI-1640 medium containing 10 % FBS in a final volume of 1 ml with mouse anti-CD40 mAbs (FGK4.5, 20 μg/ml) from BioXcell (West Lebanon, NH) and recombinant mouse IFN-γ (100 ng/ml) from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). As a control, an equivalent quantity of soluble IFN-γ was added to the medium. 24 h later, intracellular IL12p35 mRNA levels were measured using real-time PCR and normalized to β-actin gene. The identification number for Il12p35 is Mm00434169_m1. Real-time PCR was performed on the ABI 7900HT Fast Real-time PCR System using TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix and TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays probe and primer mix (Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA).

Western blotting

Protein lysates prepared using RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, pH7.4.) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were probed with specific antibodies against phospho-STAT1, phospho-P38, phospho-NF-κB p65, STAT1, p38, NF-κB p65 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), or β-actin (AC-15, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Reactions were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Differences between groups within experiments were tested for significance with Student t test using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Immunization with OVA-MPL induces a robust OVA-specific CD4+ T cell response in SRA−/− mice

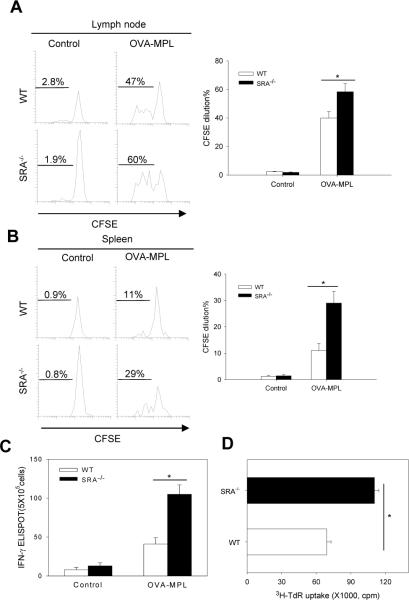

Our earlier observations of an enhanced antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response in immunized SRA/CD204 knockout mice [27] prompted us to examine whether SRA/CD204 also affected MPL-induced activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. MPL is a chemically modified form of LPS with significantly less toxicity and has been tested extensively in clinical trials as a vaccine adjuvant [29]. An adoptive T cell transfer model was initially exploited to evaluate the potential effect of SRA/CD204 on priming of OVA-specific naïve CD4+ T cells in vivo. CFSE-labeled CD4+ T cells from the OT-II transgenic mice were transferred into WT or SRA−/− mice, followed by OVA-MPL immunization. As expected, OT-II cells expanded actively in response to the OVA vaccination. However, immunized SRA−/− mice showed a stronger proliferation of OT-II cells in both draining lymph nodes (Fig. 1A) and spleen (Fig. 1B) compared with WT mice.

Figure 1. Lack of SRA/CD204 potentiates an OVA-specific CD4+ T cell response by enhancing T cell-stimulating functions of DCs.

A and B. SRA/CD204 suppresses OVA-MPL induced expansion of adoptively transferred OT-II cells. Mice (n=5) received CFSE-labeled OT-II cells, followed by OVA-MPL immunization. Draining lymph nodes (A) and spleen (B) were analyzed using FACS by gating on CD4+CSFE+ cells. Representative histograms from two separate experiments with similar results are shown (*p<0.01). C. Increased IFN-γ production by OVA-specific CD4+ T cells from SRA−/− mice. Mice (n=5) were immunized with OVA-MPL or left untreated. Splenocytes were stimulated with OVA323-339 and assayed for IFN-γ secretion using ELISPOT (*p<0.01). D. Increased T cell-stimulating activity of DCs from immunized SRA−/− mice. Splenic CD11c+ DCs were magnetically isolated from the immunized WT or SRA−/− mice and used to stimulate OT-II cells. Cell proliferation was measured using 3H-TdR uptake assays (*p<0.01). Data are means ± SE. Results representative of three independent experiments are shown.

We next determined the effect of SRA/CD204 on the endogenous OVA-specific CD4+ T cells using ELISPOT assays. In consistent with the proliferation data (Fig. 1A and B), splenocytes from OVA-MPL immunized SRA−/− mice produced significantly higher levels of IFN-γ upon stimulation with MHC-II restricted OVA323-339 peptide than those from WT mice (Fig. 1C).

Given that SRA/CD204 is highly expressed on DCs [27], we examined T cell–stimulating capability of splenic DCs purified from the OVA-MPL immunized mice using magnetic beads. Splenic DCs isolated from SRA−/− mice were more efficient than those from WT mice in stimulating naïve OT-II cells to proliferate (Fig. 1D) and to produce cytokine IL-2 (data not shown).

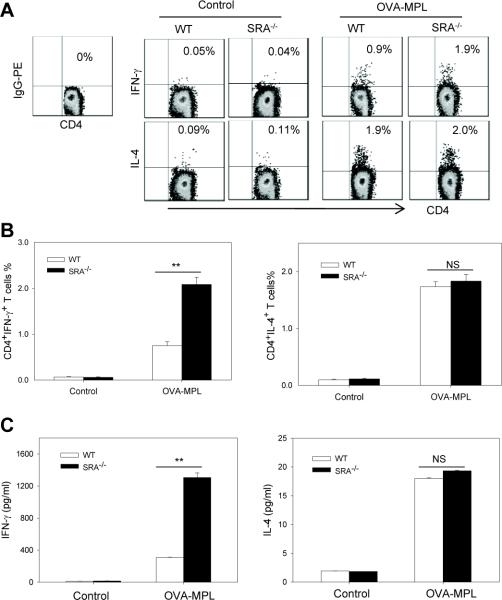

Antigen-specific CD4+ T cells from OVA-MPL immunized SRA−/− mice produce more Th1 cytokine IFN-γ

The two main types of effector CD4+ T cells (i.e., Th1 and Th2) are characterized by their ability to produce signature cytokines, such as IFN-γ and IL-4, respectively. Using intracellular cytokine staining assays we characterized the levels of IFN-γ and IL-4 in OVA323–339-stimulated splenocytes from OVA-MPL immunized WT and SRA−/− mice. The percentage of IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells in SRA−/− mice was significantly higher compared to those in WT mice after vaccination (Fig. 2A and Fig. 2B, left), whereas the percentage of IL-4 producing CD4+ T cells was similarly increased in WT and SRA−/− mice (Fig. 2A and Fig. 2B, right). In support of this result, ELISA assays showed that SRA−/− mice-derived splenocytes upon OVA323-339 stimulation produced much more IFN-γ than those from WT mice (1307.16 ±57.13 pg/ml versus 308.82±2.59 pg/ml) (Fig. 2C, left). However, the IL-4 levels were comparable in the culture supernatants of splenocytes from WT and SRA−/− mice (Fig. 2C, right), suggesting that SRA/CD204 preferentially influences IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. In addition, there were no differences in the frequency of IL-10 or IL-17A-producing CD4+ T cells in WT and SRA−/− mice before or after immunization (data not shown).

Figure 2. OVA-specific CD4+ T cells from OVA-MPL immunized SRA−/− mice produced more Th1 cytokine IFN-γ.

A and B. WT and SRA−/− mice (n=5) were immunized with OVA-MPL twice. Splenocytes were stimulated with OVA323-339 and subjected to intracellular cytokine staining assays. Representative histograms from three independent experiments are shown. B. The effect of SRA/CD204 on the percentage of OVA-specific CD4+IFN-γ+ T cells (left) and CD4+IL-4+ T cells (right) before and after vaccination are also shown (**p<0.005, NS, not significant). C. Supernatants from OVA323-339-stimulated cells were collected and assayed for the levels of IFN-γ (left) and IL-4 (right) by ELISA (**p<0.005). Data are means ± SE and represent three independent experiments.

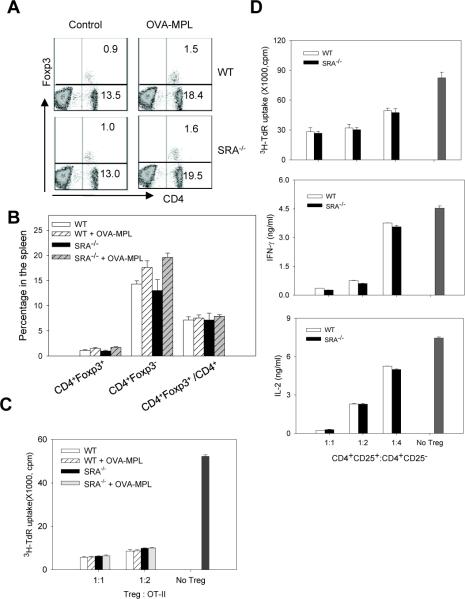

The absence of SRA/CD204 does not affect CD4+CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs)

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs are known to play a critical role in maintaining peripheral tolerance during immune homeostasis. Therefore, we assessed the potential effect of SRA/CD204 on Tregs. There was no significant difference in the percentage of splenic Tregs between WT and SRA−/− mice before or after OVA-MPL immunization (Fig. 3A and 3B). Similar observations were made in peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) and lymph nodes (data not shown). To examine whether the function of Tregs might be altered in the absence of SRA/CD204, enriched Tregs were co-cultured with OVA323-339-stimulated OT-II cells. Tregs from SRA−/− mice suppressed the proliferation of OT-II cells as efficiently as those from WT mice (Fig. 3C). To further determine whether SRA/CD204 influenced the sensitivity of CD4+ effector T cells to Tregs following vaccination, CD4+CD25− effector T cells were isolated from OVA-MPL immunized WT or SRA−/− mice, and cultured with Tregs derived from WT mice. CD4+CD25− effector T cells from WT and SRA−/− mice showed similar susceptibility to the suppressive activity of Tregs (Fig. 3D), as indicated by cell proliferation and cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-2) production assays.

Figure 3. SRA/CD204 deficiency does not affect Tregs and their suppressive activity.

A and B. Following OVA-MPL immunization (n=3), Tregs in the spleen were stained with CD4 and Foxp3 antibodies. Representative histograms from two experiments with similar results are shown (A). The percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ and CD4+Foxp3− cells in total splenocytes, as well as the percentage of CD4+Foxp3+ in total CD4+ cells are also analyzed (B). C. CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were isolated from control or OVA-MPL immunized mice, and co-cultured with OT-II cells. Proliferation of OT-II cells in response to OVA323-339 stimulation was measured using 3H-TdR uptake assays. D. CD4+CD25− cells and CD4+CD25+ Tregs were isolated from OVA-MPL immunized mice, co-cultured at different ratios as indicated. Proliferation of CD4+CD25− effector T cells upon stimulation of CD3/CD28 mAb was examined using 3H-TdR uptake assays (top). IFN-γ (middle) and IL-2 (bottom) levels in the culture supernatants were measured by ELISA. Results representative of two independent experiments with similar results are shown.

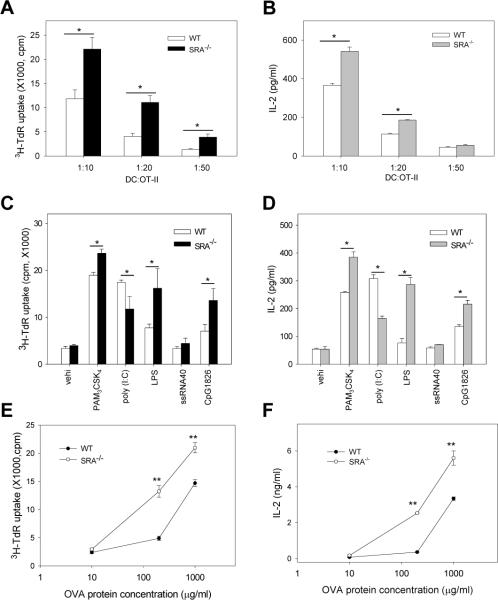

SRA/CD204 suppresses the ability of DCs to stimulate OVA-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro

Given the enhanced OVA-specific CD4+ T response in OVA-MPL-immunized SRA−/− mice, we compared the ability of BM-DCs to stimulate OVA-specific naïve OT-II cells in vitro. Upon OVA protein-pulsing and subsequent LPS treatment to activate DCs, SRA−/− DCs were more effective than WT DCs in stimulating OT-II cell proliferation, as indicated by a significant increase in the incorporation of 3H-TdR (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the data from the OT-II cell proliferation assays, higher levels of IL-2 was present in the supernatants when OT-II cells were co-cultured with SRA−/− DCs than with WT DCs (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. SRA/CD204 suppresses the ability of DCs to stimulate OVA-specific CD4+ T cells in vitro in the presence or absence of LPS treatment.

A and B. Immunogenicity of LPS-stimulated SRA−/− DCs following OVA protein loading. BM-DCs were pulsed with OVA protein (10 μg/ml) and treated with LPS. DCs were then cultured with OT-II cells at different ratios for 72 h. Cell proliferation was measured using 3H-TdR uptake assays (A). Supernatants were collected after 48 h and assayed for IL-2 using ELISA (B). *p<0.01. Data are means ± SE. Results representative of three independent experiments are shown. C and D. Effects of SRA/CD204 on DC-mediated T cell stimulation by other TLR ligands. BM-DCs were pulsed with OVA protein and stimulated with PAM3CSK4, poly (I:C), LPS, ssRNA40 or CpG1826. DCs were then cultured with OT-II cells at a ratio of 1:20 for 72 h. Cell proliferation (C) and IL-2 production (D) were assayed. *p<0.01. Data are shown as means ± SE and represent the results from two independent experiments with similar results. E and F. Immunostimulatory activity of SRA−/− DCs without LPS stimulation. DCs were pulsed with different concentrations of OVA protein for 3 h, and co-cultured with OT-II at 1:10 ratio for 72 h. Cell proliferation and IL-2 production were analyzed using 3H-TdR uptake assays (E) and ELISA (F), respectively. **p<0.005. Data are shown as means ± SE and represent the results from two independent experiments.

We extended our analysis of SRA/CD204 effect on DC functions in response to the stimulation with other TLR ligands, including PAM3CSK4 (TLR1/TLR2), poly (I:C) (TLR3), ssRNA40 (TLR7) and CpG1826 (TLR9). It was seen that SRA−/− DCs stimulated OT-II cells more effectively than WT DCs following treatment with PAM3CSK4 and CpG1826, as indicated by T cell proliferation and IL-2 production (Fig. 4C and 4D). However, poly(I:C)-treated SRA−/− DCs stimulated a weaker CD4+ T cell activation than WT DCs. It was most likely due to the fact that SRA/CD204 functions as a surface receptor for double stranded RNA (dsRNA) and is required for the entry of poly(I:C) as well as subsequent induction of a pro-inflammatory response [30, 31]. In addition, ssRNA40-treated DCs did not appear to efficiently induce a robust CD4+ T cell activation, which could be explained by low expression levels of TLR7 in bone marrow-derived DCs used in our studies [32].

We next examined whether SRA/CD204 could negatively regulate the immunogenicity of DCs in the absence of inflammatory stimulation (e.g., LPS). WT and SRA−/− DCs stimulated activation of naïve OT-II cells in an antigen dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4E and 4F). DCs pulsed with low dose of endotoxin-free OVA protein (10 μg/ml) failed to stimulate OT-II cells in the absence of LPS treatment, which is known to provide additional co-stimulatory or inflammatory signals for functional activation of DCs. However, significant stimulation of OT-II cells by DCs was observed when OVA protein was present at high concentrations (Fig. 4E and 4F), indicating that high concentrations of antigen were required for T cell stimulation in the absence of LPS. These results are also consistent with a recent study showing the low efficiency of antigen presentation in DCs without stimulation with pathogen-associated molecule, such as LPS [33]. Surprisingly, the enhanced ability of SRA−/− DCs to stimulate OT-II cell proliferation in the absence of LPS was evident when DCs encountered high concentrations of OVA protein, indicated by OT-II cell proliferation (Fig. 4E) and IL-2 production (Fig. 4F). We also examined mice immunized with OVA in the absence of MPL, however, no significant difference in OVA-specific immune response was seen in WT and SRA−/− mice (data not shown), probably due to the weak immunogenicity of antigen in the absence of immunostimulatory adjuvant as well as the various tolerance mechanisms in vivo.

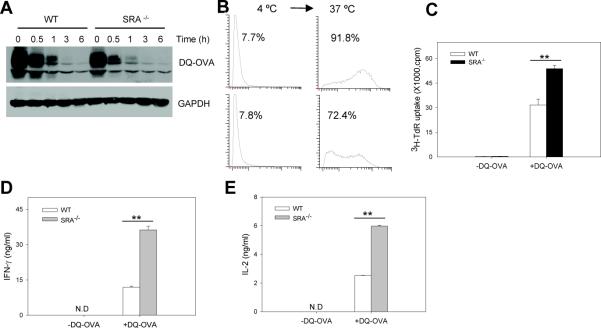

Effect of SRA/CD204 on the receptor-mediated endocytosis of soluble antigen by DCs

BODIPY-conjugated OVA (DQ-OVA) is a self-quenched conjugate of ovalbumin that exhibits bright green fluorescence upon proteolytic degradation. Considering the previously reported endocytic activity of SRA/CD204, we evaluated the potential impact of SRA/CD204 on receptor-mediated endocytosis of DQ-OVA. DCs were incubated with DQ-OVA at 4 °C in which only receptor-mediated binding occurred. After washing to remove unbound proteins, DCs were transferred to 37 °C and cultured for various times as indicated. Immunoblotting analysis of the levels of DQ-OVA showed that the lack of SRA/CD204 resulted in a modest reduction in the binding of DQ-OVA to DCs at 4 °C (Fig. 5A). As a result, DQ-OVA internalization was decreased accordingly in SRA−/− DCs compared with WT DCs when cells were shifted to 37 °C (Fig. 5A). As expected, FACS analysis showed that WT DCs also exhibited greater fluorescence than SRA−/− DCs 1 h after cells were transferred to 37 °C, indicating the degradation of internalized DQ-OVA (Fig. 5B), which is consistent with the immunoblotting result (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. SRA/CD204 reduces the ability of DQ-OVA protein-pulsed DCs to activate CD4+ T cells.

A and B. Modest reduction in binding and uptake of DQ-OVA in the absence of SRA/CD204. WT or SRA−/− BM-DCs were incubated with DQ-OVA (20 μg/ml) at 4 °C for 30 min. Cells were washed and incubated at 37 °C for indicated times. Cells were examined for the levels of DQ-OVA by immunoblotting (A). B. Following incubation with DQ-OVA at 4 °C, cells were washed and culture at 37 °C for 1 h. FACS analysis was used to examine the fluorescence in WT and SRA−/− DCs. Representative histograms of three separate experiments with similar results are shown. C, D and E. Increased T cell-stimulating capability of SRA−/− DCs. BM-DCs were incubated with DQ-OVA at 37 °C for 3 h. After washing, cells were cultured with OT-II cells at a ratio of 1:5. T cell proliferation was examined based on 3H-TdR uptake (C). Supernatants were assayed for IFN-γ (D) and IL-2 (E) using ELISA. **p<0.005. Data are shown as means ± SE and represent the results from two independent experiments.

SRA/CD204 absence enhances T cell-stimulating activity of DCs independent of antigen processing

We next asked the question of whether the decreased uptake of DQ-OVA in the absence of SRA/CD204 might lead to reduced T cell-stimulating capability of DCs. Surprisingly, even without LPS treatment, DQ-OVA-pulsed SRA−/− DCs were more efficient than WT DCs in activating naive OT-II cells, as evidenced by increased OT-II cell proliferation (Fig. 5C) as well as cytokine production of IFN-γ (Fig. 5D) and IL-2 (Fig. 5E). DQ-OVA appeared to be more immunogenic than OVA in that DCs exposed to low dose of DQ-OVA (20 μg/ml) were able to effectively stimulate OT-II cells, whereas high concentrations of un-modified OVA (100–200 μg/ml) were required to induce OT-II proliferation (Fig. 4C and 4D). It could be attributed to the chemical modification of protein (e.g., BODIPY-conjugation of OVA), which is known to alter the immunogenicity of antigen.

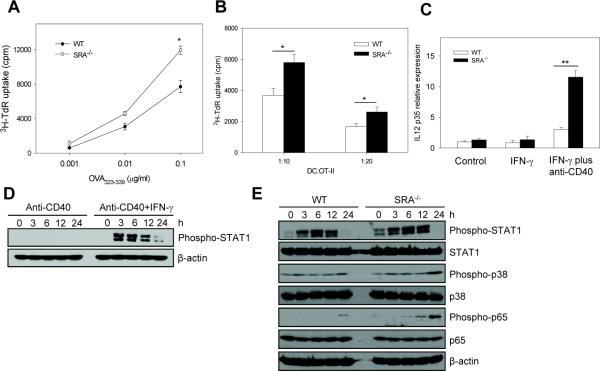

To further assess the SRA/CD204 effect on T cell-stimulating capability of DCs in the absence of LPS treatment, DCs were pulsed with different concentrations of MHC II-restricted OVA323–339 peptide. SRA−/− 323–339 DCs without LPS treatment displayed significantly higher activity than WT cells in stimulating OT-II cell proliferation only when high concentrations of OVA323–339 peptide were present (Fig. 6A), which is consistent with the antigen pulsing study using OVA protein. In addition, SRA−/− DCs pulsed with a high dose of OVA323–339 peptide also showed more efficient T cell-stimulatory activity compared with WT DCs, when co-cultured with OT-II cells at different ratios (Fig. 6B). These results suggest that regulation of T cell-stimulating functions of DCs by SRA/CD204 may not involve endocytic and antigen processing pathways.

Figure 6. SRA/CD204 limits the ability of OVA323-339 peptide-pulsed DCs to activate CD4+ T cells.

A. WT and SRA−/− BM-DCs were pulsed with different concentrations of OVA323-339 peptide for 3 h. Cell proliferation was measured after culture with OT-II cells at a ratio of 1:10. *p<0.01. B. BM-DCs pulsed with OVA323-339 peptide (0.1 μg/ml) were cultured with OT-II cells at different ratios, followed by cell proliferation assays. *p<0.01. C. Day 7 BM-DCs were treated with IFN-γ or IFN-γ plus anti-CD40 mAbs for 24 h. IL12p35 mRNA expression was analyzed using quantitative real-time RT-PCR. **p<0.005. Gene expression was normalized relative to the expression of β-actin. Data are shown as means ± SE and represent the results from two independent experiments with similar results. D. BM-DCs were treated with anti-CD40 mAbs or anti-CD40 Abs plus IFN-γ for indicated times. Phosphorylation of STAT1 was examined using immunoblotting. E. SRA/CD204 suppresses activation of STAT1, p38 and NF-κB. WT and SRA−/− DCs were treated with anti-CD40 mAbs plus IFN-γ. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for phosphorylation of STAT1, p38 and NF-κB p65 using immunoblotting. β-actin serves as a loading control.

SRA/CD204 downregulates IL12p35 gene expression by inhibiting JAK/STAT1, MAPK p38 and NF-κB signaling upon CD40 ligation and IFN-γ stimulation

It has been reported that DC activation can also be induced by CD4+ T helper cells [34, 35]. It was proposed that CD40L-CD40 interaction induced DC activation is a physiologic event that occurs when activated CD4+ T cells interact with DCs [34, 35]. Therefore, we examined whether stimulatory signals provided by CD4+ T helper cells could alter DC activation status in the absence of SRA/CD204. In our study, treatment of anti-CD40 mAbs alone failed to induce the expression of IL12p35 (data not shown). This is consistent with the previous report by Osada et al showing that induction of IL-12 via CD40-CD40L interaction in DCs required IFN-γ as a complementary signal [36]. Therefore, IFN-γ alone or IFN-γ in combination with anti-CD40 mAbs were used to stimulate WT and SRA−/− DCs. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis showed that treatment with IFN-γ alone did not induce Il12p35 expression, however, treatment with IFN-γ plus anti-CD40 mAbs induced higher mRNA levels of Il12p35 in SRA−/− DCs than in WT DCs (Fig. 6C).

It was recently demonstrated that activation of JAK/STAT1 signaling was critical for CD40 signal induced IL-12 production [37]. To provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying SRA/CD204-mediated immune regulation, we investigated the activation of STAT1 signaling pathways in WT and SRA−/− cells after stimulation using anti-CD40 mAbs in combination with IFN-γ. We initially confirmed that anti-CD40 mAbs plus IFN-γ, but not anti-CD40 mAbs alone, could induce STAT1 phosphorylation in DCs (Fig. 6D). This observation also provides an explanation of why anti-CD40 mAbs alone failed to efficiently induce the IL-12 expression. Strikingly, treatment with anti-CD40 mAbs plus IFN-γ resulted in stronger activation of STAT1 in SRA−/− DCs than in WT cells, as indicated by increased phosphorylation of STAT1 (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, increased activation of MAP kinase p38 and NF-κB p65 were also seen in stimulated SRA−/− DCs compared to WT counterparts (Fig. 6E).

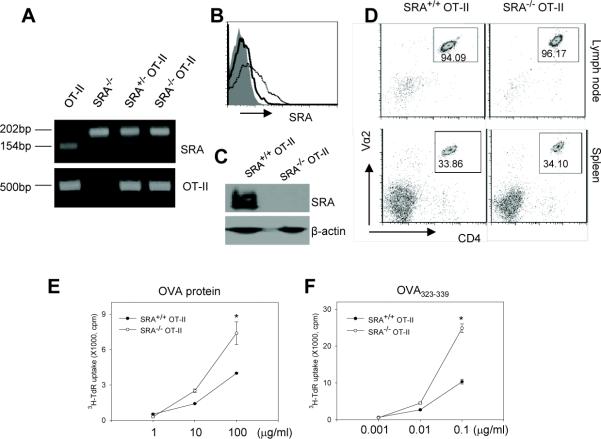

OT-II cells from the SRA−/−OT-II transgenic mice display increased proliferation upon OVA stimulation

To further determine the regulatory effect of SRA/CD204 on antigen-specific CD4+ T cell activation, we generated the homozygous SRA−/− OT-II transgenic mice by cross-breeding the SRA−/− mice and the OT-II mice. Genotyping analysis confirmed that the mice carried both SRA/CD204 deficiency and OT-II TCR (Fig. 7A). FACS (Fig. 7B) and immunoblotting (Fig. 7C) analyses also validated the absence of SRA/CD204 expression on splenocytes from the SRA−/− OT-II transgenic mice. It should be noted that, although rat mAbs 2F8 was reported to fail to react with SRA/CD204 on cells or tissues from C57BL/6 mice because of the SRA/CD204 polymorphism [38], our present and previous work [27] as well as studies from other independent groups [39–42] showed that these antibodies could recognize SRA/CD204 on C57BL/6 mice-derived cells in immunofluorescence staining and FACS assays. The reason for the discrepancy is not clear. The lack of SRA/CD204 had little effect on the development of OT-II cells (Fig. 7D). Upon stimulation with OVA protein (Fig. 7E) or OVA323–339 peptide (Fig. 7F), splenocytes from the SRA−/− OT-II transgenic mice showed a more robust proliferation than those from the SRA+/+ OT-II mice when high concentrations of antigens were present, which was consistent with the results obtained from studies of OVA protein or peptide-pulsed DCs (Fig. 4C and Fig. 6A).

Figure 7. Splenocytes from the SRA−/− OT-II mice display increased proliferation upon OVA stimulation.

A. PCR genotyping analysis of the SRA−/− OT-II transgenic mice. The band of 154bp indicates WT allele in WT SRA+/+ mouse or heterozygous SRA+/− mouse. The band of 202bp indicates the mutant allele. B. Expression of SRA/CD204 on splenocytes from SRA+/+ OT-II (dotted line) and SRA−/− OT-II (solid line) transgenic mice were examined using FITC-labeled anti-SRA/CD204 antibodies and FACS analysis. Shaded area represents the IgG isotype control. C. Immunoblotting analysis of SRA/CD204 protein expression using splenocytes from the SRA+/+ OT-II and SRA−/− OT-II mice. D. SRA/CD204 absence does not affect the development of OT-II cells. Cells prepared from lymph nodes and spleen of the SRA+/+ OT-II and SRA−/− OT-II mice were stained for TCR-Vα2 and CD4 expression and analyzed by FACS. The numbers in the gates represent the percentage of CD4+ OT-II T cells. E and F. 2×105 splenocytes from the SRA+/+ OT-II or SRA−/− OT-II mice were incubated with different concentrations of OVA protein (E) or OVA323-339 peptide (F) as indicated in the absence of LPS. Cell proliferation was examined using 3H-TdR uptake assays (*p<0.01). Data are presented as means ± SE. Results representative of two independent experiments are shown.

Discussion

SRA/CD204 is an important PPR known to bind a wide range of pathogen associated molecules as well as self-molecules, and exhibits multifunctional roles in the cellular processes and host response [43]. The present study has extended our early findings of SRA/CD204 as a negative regulator of adaptive immunity [26–28], and demonstrated that SRA/CD204 is capable of downregulating antigen-specific CD+ T cell response. Furthermore, we have provided the first evidence showing that SRA/CD204 can alter the intrinsic immunogenicity of mouse DCs in the context of activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells.

In support of our previous observation that lack of SRA/CD204 resulted in enhanced OVA-specific CD8+ T cell responses following OVA-MPL vaccination [27], we have shown that SRA/CD204 knockout mice developed a more potent OVA323–339-specific CD4+ T cell response compared to WT mice, as indicated by robust proliferation and IFN-γ production of adoptively transferred OT-II cells as well as endogenous OVA-specific CD4+ T cells. The similar enhancement of OVA-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation in the absence of SRA/CD204 indicates that there is no apparent preference of the SRA/CD204 effect on these T effector cells, at least in the context of OVA-MPL vaccination. Interestingly, the lack of SRA/CD204 does not influence the induction and regulatory activity of CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ Tregs in the experimental setting examined in the present study.

The enhanced OVA-specific CD4+ T cell response observed in OVA-MPL immunized SRA−/− mice may be attributed to the altered immunogenicity of APCs, e.g., DC, which expresses high levels of SRA/CD204. Indeed, splenic DCs isolated from the OVA-MPL immunized SRA−/− mice are much more efficient than those from WT mice in stimulating naïve OT-II cells, confirming the involvement of DCs in the SRA/CD204-mediated immune regulation. In addition, OT-II cells display greater proliferation and higher levels of cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) when stimulated with SRA−/− DCs after OVA protein loading and LPS treatment, which is consistent with the proposed role that SRA/CD204 plays in the attenuation of immunostimulatory adjuvant (e.g., MPL or LPS) induced inflammatory signaling in DCs and subsequent DC maturation/activation [27]. These results are also in line with other reports showing that SRA/CD204 serves as a negative regulator during inflammatory responses [6, 44–46] and as a limiting factor in LPS-induced DC maturation [47]. Indeed, our recent studies demonstrated that SRA/CD204 directly interfered the ubiquitination of TRAF6, a signaling adaptor downstream of TLR4, resulting in attenuation of the activity of NF-κB and consequent activation of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IP-10) [48].

Several lines of evidence suggest that antigen modification for targeting to scavenger receptors for improved delivery and uptake leads to the induction of an increased T cell response [19–21, 49]. Scavenger receptor-mediated endocytosis of OVA was recently shown to target OVA to lysosomes for MHC II–restricted presentation [18]. However, the precise role of individual receptors, such as SRA/CD204, was not examined in this context. Our study of binding and uptake of BODIPY-modified OVA (i.e., DQ-OVA) showed that SRA/CD204 contributes to the recognition and capture of DQ-OVA, as indicated by immunoblotting and FACS analyses. However, the reduced antigen binding and uptake did not impair the ability of SRA−/− DCs to process OVA for MHC II–restricted presentation, suggesting that other redundant endocytic receptors also participate in this process. In contrast, DQ-OVA-loaded SRA−/− DCs are more efficient than WT DCs in stimulating OT-II cells, even in the absence of LPS treatment. Similar observations have also been made when DCs are incubated in the presence of high concentrations of endotoxin-free OVA protein. Furthermore, SRA−/− DCs carrying MHC II restricted OVA323–339 peptide also stimulate the proliferation and cytokine production of OT-II cells more effectively than WT counterparts. Besides CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses against the model antigen OVA, the effects of SRA/CD204 was also similarly observed in the activation of CD8+ T cells recognizing gp100, an antigen naturally expressed in human and mouse melanoma [27]. Collectively, SRA/CD204 appears to be directly involved in the negative regulation of T cell activation by DCs. The evidence supporting our conclusion also came from our previous studies of the impact of SRA/CD204 on stress protein-based vaccine activity. Despite SRA/CD204 has been shown to participate in binding and internalization of stress proteins [23, 24], the lack of SRA/CD204, however, led to a greater antitumor response augmented by stress protein vaccines [26]. Given that scavenger receptors represent a rapidly expanding protein family, it is likely that individual scavenger receptors may display distinct activities in sensing of stress signals or sampling of extracellular antigens, therefore resulting in distinct immune outcomes. Indeed, it was recently shown that two other scavenger receptor members, LOX-1 and SREC, were required for hsp70-mediated antigen cross-presentation and T cell activation [22, 25].

We also present the first evidence showing that SRA/CD204 acts as a suppressor of T cell-stimulating capability of DCs in the absence of inflammatory stimulus provided by LPS, an agonist for TLR4. However, this suppressive effect is more evident when antigens (e.g., OVA protein or OVA323–339 peptide) are present in relatively high concentrations. It is not surprising because a high dose of antigen is generally required to stimulate T cells if co-stimulation signals are lacking or weak. Moreover, splenocytes from the SRA−/− OT-II transgenic mice proliferate more rigorously than those from the SRA+/+ OT-II mice upon stimulation with high concentrations of OVA antigens in the absence of LPS, which further underscores the functional significance of SRA/CD204 in the stimulation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cell. Our findings indicate that SRA/CD204 not only attenuates immunostimulatory adjuvant or cell lysate-triggered DC activation as previously described [27, 28, 48], but also acts as an intrinsic immunoregulator to limit DC functions during physiologic stimulation of CD4+ T cells.

It is suggested that CD40L on activated CD4+ T cells binds to CD40 on DCs, therefore promoting DC activation [34, 35]. In the present study, SRA−/− DCs express higher levels of IL12p35 than WT counterparts upon stimulation with anti-CD40 mAbs in combination with IFN-γ, which mimics a physiologic mode of DC-T cell interaction. This result is consistent with earlier observations of enhanced IL-12 levels in SRA−/− DCs and macrophages after stimulation with pathogen-associated molecules [27, 44]. Furthermore, we demonstrate that absence of SRA/CD204 in DCs markedly increased signaling activation of STAT1 and p38, both of which have been shown to play important roles in IL-12 production [37, 50]. These findings provide a molecular basis for SRA/CD204-mediated suppression of DC functions during interactions with CD4+ T cells (e.g., CD40 ligation and IFN-γ signal). In addition, it has been documented tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) is required for CD40-induced activation of NF-κB and p38 pathways [51, 52], and interference with CD40-TRAF6 signaling results in the polarization of macrophages toward an anti-inflammatory regulatory M2 signature [53]. Interestingly, we recently found that SRA/CD204 downregulated LPS-induced activation of NF-κB and production of inflammatory cytokines via blocking TRAF6 functions [48]. Indeed, the activation of NF-κB in anti-CD40 plus IFN-γ treated DCs, as indicated by the phosphorylation of p65, was also significantly increased in the absence of SRA/CD204. Therefore, our data not only establish an immune-suppressive role of SRA/CD204 in DCs by attenuating the production of Th1 cytokine (i.e., IL-12) through blocking activation of STAT1, NF-κB and p38 signaling pathways, but also reinforce the less appreciated feature of this molecule in signaling modulation.

SRA/CD204 is generally considered as phenotypic marker for M2 macrophages [54], which is shown to suppress T cell activation by producing lower levels of IL-12 and higher levels of IL-10. Intriguingly, SRA/CD204 knockout mice displayed reduced levels of LPS-induced IL-10 compared to WT mice [55]. M2 macrophages, together with other immune regulatory cells, including tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) and tumor-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are involved in the suppression of antitumor T cell response, thus facilitating tumor progression and invasion [56, 57]. We propose that, besides acting as a pattern recognition molecule, SRA/CD204 represents a negative immune modulator on DCs and possibly other myeloid cells as well in the context of T cell activation. Indeed, DCs from tumor tissues had substantially higher levels of SRA/CD204 than cells from secondary lymphoid tissues, which correlated with increased suppressive activities of those DCs from the tumor microenvironment [58]. We also observed an increased expression of SRA/CD204 in DCs and macrophages exposed to tumor or tumor conditioned medium (H.W. and X.-Y.W., unpublished data). However, more studies are necessary to define the molecular mechanisms of SRA/CD204 action on APCs in different immunological contexts.

Taken together, we have critically assessed the immune regulatory functions of SRA/CD204 using independent model systems and established an important role for SRA/CD204 in suppressing the stimulatory capacity of DCs as well as the activation of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Our studies provide new insights into the under-appreciated features of scavenger receptors on DCs, SRA/CD204 in particular, in modulation of the adaptive immunity. Unraveling the precise immunologic activities of SRA/CD204 and other pattern recognition scavenger receptors should provide new opportunities to develop potential strategies to target the activity of this diverse family of receptors for therapeutic benefits in treating cancer and other diseases.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grants CA129111, CA154708, CA099326, American Cancer Society Scholarship RSG-08-187-01-LIB, Harrison Endowed Scholarship and NCI Cancer Center Support Grants to Massey Cancer Center.

Abbreviations

- PRR

pattern recognition receptor

- SRA

scavenger receptor A

- DC

dendritic cell

- MPL

Monophosphoryl lipid A

Footnotes

Authorship: H.Y., D.Z., X.Y., F.H., performed experiments and analyzed data. M.M., Z.C., J.S. contributed to data analyses. X-Y.W. designed and supervised the research. X-Y.W., H.Y. and D.Z., wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Greaves DR, Gordon S. The macrophage scavenger receptor at 30 years of age: current knowledge and future challenges. J Lipid Res. 2009;50(Suppl):S282–286. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800066-JLR200. DOI R800066-JLR200 [pii] 10.1194/jlr.R800066-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldstein JL, Ho YK, Basu SK, Brown MS. Binding site on macrophages that mediates uptake and degradation of acetylated low density lipoprotein, producing massive cholesterol deposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76:333–337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Takeya M, Kamada N, Kataoka M, Jishage K, Ueda O, Sakaguchi H, Higashi T, Suzuki T, Takashima Y, Kawabe Y, Cynshi O, Wada Y, Honda M, Kurihara H, Aburatani H, Doi T, Matsumoto A, Azuma S, Noda T, Toyoda Y, Itakura H, Yazaki Y, Steinbrecher UP, Ishinash S, Maeda N, Gordon S, Kodama T. A role for macrophage scavenger receptors in atherosclerosis and susceptibility to infection. Nature. 1997;386:292–296. doi: 10.1038/386292a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas CA, Li Y, Kodama T, Suzuki H, Silverstein SC, El Khoury J. Protection from lethal gram-positive infection by macrophage scavenger receptor-dependent phagocytosis. J Exp Med. 2000;191:147–156. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peiser L, De Winther MP, Makepeace K, Hollinshead M, Coull P, Plested J, Kodama T, Moxon ER, Gordon S. The class A macrophage scavenger receptor is a major pattern recognition receptor for Neisseria meningitidis which is independent of lipopolysaccharide and not required for secretory responses. Infect Immun. 2002;70:5346–5354. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.10.5346-5354.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haworth R, Platt N, Keshav S, Hughes D, Darley E, Suzuki H, Kurihara Y, Kodama T, Gordon S. The macrophage scavenger receptor type A is expressed by activated macrophages and protects the host against lethal endotoxic shock. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1431–1439. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hickman SE, Allison EK, El Khoury J. Microglial dysfunction and defective beta-amyloid clearance pathways in aging Alzheimer's disease mice. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8354–8360. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. DOI 28/33/8354 [pii] 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0616-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kobayashi H, Sakashita N, Okuma T, Terasaki Y, Tsujita K, Suzuki H, Kodama T, Nomori H, Kawasuji M, Takeya M. Class A scavenger receptor (CD204) attenuates hyperoxia-induced lung injury by reducing oxidative stress. J Pathol. 2007;212:38–46. doi: 10.1002/path.2150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu C, Hua F, Liu L, Ha T, Kalbfleisch J, Schweitzer J, Kelley J, Kao R, Williams D, Li C. Scavenger receptor class-A has a central role in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1972–1981. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.59. DOI jcbfm201059 [pii] 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu J, Zheng SL, Komiya A, Mychaleckyj JC, Isaacs SD, Hu JJ, Sterling D, Lange EM, Hawkins GA, Turner A, Ewing CM, Faith DA, Johnson JR, Suzuki H, Bujnovszky P, Wiley KE, DeMarzo AM, Bova GS, Chang B, Hall MC, McCullough DL, Partin AW, Kassabian VS, Carpten JD, Bailey-Wilson JE, Trent JM, Ohar J, Bleecker ER, Walsh PC, Isaacs WB, Meyers DA. Germline mutations and sequence variants of the macrophage scavenger receptor 1 gene are associated with prostate cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2002;32:321–325. doi: 10.1038/ng994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beuten J, Gelfond JAL, Franke JL, Shook S, Johnson-Pais TL, Thompson IM, Leach RJ. Single and Multivariate Associations of MSR1, ELAC2, and RNASEL with Prostate Cancer in an Ethnic Diverse Cohort of Men. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2010;19:588–599. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0864. DOI 10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palm NW, Medzhitov R. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:221–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. DOI IMR731 [pii] 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392:245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ravetch JV, Bolland S. IgG Fc receptors. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:275–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonifaz L, Bonnyay D, Mahnke K, Rivera M, Nussenzweig MC, Steinman RM. Efficient targeting of protein antigen to the dendritic cell receptor DEC-205 in the steady state leads to antigen presentation on major histocompatibility complex class I products and peripheral CD8+ T cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1627–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geijtenbeek TB, Torensma R, van Vliet SJ, van Duijnhoven GC, Adema GJ, van Kooyk Y, Figdor CG. Identification of DC-SIGN, a novel dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 receptor that supports primary immune responses. Cell. 2000;100:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80693-5. DOI S0092-8674(00)80693-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgdorf S, Kautz A, Bohnert V, Knolle PA, Kurts C. Distinct pathways of antigen uptake and intracellular routing in CD4 and CD8 T cell activation. Science. 2007;316:612–616. doi: 10.1126/science.1137971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abraham R, Singh N, Mukhopadhyay A, Basu SK, Bal V, Rath S. Modulation of immunogenicity and antigenicity of proteins by maleylation to target scavenger receptors on macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;154:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shakushiro K, Yamasaki Y, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. Efficient scavenger receptor-mediated uptake and cross-presentation of negatively charged soluble antigens by dendritic cells. Immunology. 2004;112:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01871.x. DOI 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01871.x IMM1871 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamasaki Y, Ikenaga T, Otsuki T, Nishikawa M, Takakura Y. Induction of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes by immunization with negatively charged soluble antigen through scavenger receptor-mediated delivery. Vaccine. 2007;25:85–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.017. DOI S0264-410X(06)00838-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delneste Y, Magistrelli G, Gauchat J, Haeuw J, Aubry J, Nakamura K, Kawakami-Honda N, Goetsch L, Sawamura T, Bonnefoy J, Jeannin P. Involvement of LOX-1 in dendritic cell-mediated antigen cross-presentation. Immunity. 2002;17:353–362. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berwin B, Hart JP, Rice S, Gass C, Pizzo SV, Post SR, Nicchitta CV. Scavenger receptor-A mediates gp96/GRP94 and calreticulin internalization by antigen-presenting cells. Embo J. 2003;22:6127–6136. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Facciponte JG, Wang XY, Subjeck JR. Hsp110 and Grp170, members of the Hsp70 superfamily, bind to scavenger receptor-A and scavenger receptor expressed by endothelial cells-I. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2268–2279. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong J, Zhu B, Murshid A, Adachi H, Song B, Lee A, Liu C, Calderwood SK. T cell activation by heat shock protein 70 vaccine requires TLR signaling and scavenger receptor expressed by endothelial cells-1. J Immunol. 2009;183:3092–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901235. DOI jimmunol.0901235 [pii] 10.4049/jimmunol.0901235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XY, Facciponte J, Chen X, Subjeck JR, Repasky EA. Scavenger receptor-A negatively regulates antitumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4996–5002. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi H, Yu X, Gao P, Wang Y, Baek SH, Chen X, Kim HL, Subjeck JR, Wang XY. Pattern recognition scavenger receptor SRA/CD204 down-regulates Toll-like receptor 4 signaling-dependent CD8 T-cell activation. Blood. 2009;113:5819–5828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190033. DOI blood-2008-11-190033 [pii] 10.1182/blood-2008-11-190033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo C, Yi H, Yu X, Hu F, Zuo D, Subjeck JR, Wang XY. Absence of scavenger receptor A promotes dendritic cell-mediated cross-presentation of cell-associated antigen and antitumor immune response. Immunol Cell Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1038/icb.2011.10. DOI icb201110 [pii] 10.1038/icb.2011.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldridge JR, McGowan P, Evans JT, Cluff C, Mossman S, Johnson D, Persing D. Taking a Toll on human disease: Toll-like receptor 4 agonists as vaccine adjuvants and monotherapeutic agents. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2004;4:1129–1138. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.7.1129. DOI doi:10.1517/14712598.4.7.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Limmon GV, Arredouani M, McCann KL, Corn Minor RA, Kobzik L, Imani F. Scavenger receptor class-A is a novel cell surface receptor for double-stranded RNA. FASEB J. 2008;22:159–167. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8348com. DOI fj.07-8348com [pii] 10.1096/fj.07-8348com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeWitte-Orr SJ, Collins SE, Bauer CM, Bowdish DM, Mossman KL. An accessory to the 'Trinity': SR-As are essential pathogen sensors of extracellular dsRNA, mediating entry and leading to subsequent type I IFN responses. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000829. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000829. DOI 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boonstra A, Asselin-Paturel C, Gilliet M, Crain C, Trinchieri G, Liu Y-J, O'Garra A. Flexibility of Mouse Classical and Plasmacytoid-derived Dendritic Cells in Directing T Helper Type 1 and 2 Cell Development. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2003;197:101–109. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021908. DOI 10.1084/jem.20021908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgdorf S, Scholz C, Kautz A, Tampe R, Kurts C. Spatial and mechanistic separation of cross-presentation and endogenous antigen presentation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:558–566. doi: 10.1038/ni.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cella M, Scheidegger D, Palmer-Lehmann K, Lane P, Lanzavecchia A, Alber G. Ligation of CD40 on dendritic cells triggers production of high levels of interleukin-12 and enhances T cell stimulatory capacity: T-T help via APC activation. J Exp Med. 1996;184:747–752. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osada T, Nagawa H, Takahashi T, Tsuno NH, Kitayama J, Shibata Y. Dendritic cells cultured in anti-CD40 antibody-immobilized plates elicit a highly efficient peptide-specific T-cell response. J Immunother. 2002;25:176–184. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conzelmann M, Wagner AH, Hildebrandt A, Rodionova E, Hess M, Zota A, Giese T, Falk CS, Ho AD, Dreger P, Hecker M, Luft T. IFN-gamma activated JAK1 shifts CD40-induced cytokine profiles in human antigen-presenting cells toward high IL-12p70 and low IL-10 production. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:2074–2086. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.040. DOI S0006-2952(10)00578-2 [pii] 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daugherty A, Whitman SC, Block AE, Rateri DL. Polymorphism of class A scavenger receptors in C57BL/6 mice. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1568–1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Usui HK, Shikata K, Sasaki M, Okada S, Matsuda M, Shikata Y, Ogawa D, Kido Y, Nagase R, Yozai K, Ohga S, Tone A, Wada J, Takeya M, Horiuchi S, Kodama T, Makino H. Macrophage Scavenger Receptor-A-Deficient Mice Are Resistant Against Diabetic Nephropathy Through Amelioration of Microinflammation. Diabetes. 2007;56:363–372. doi: 10.2337/db06-0359. DOI 10.2337/db06-0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moldenhauer LM, Keenihan SN, Hayball JD, Robertson SA. GM-CSF is an essential regulator of T cell activation competence in uterine dendritic cells during early pregnancy in mice. J Immunol. 2011;185:7085–7096. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001374. DOI jimmunol.1001374 [pii] 10.4049/jimmunol.1001374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sindrilaru A, Peters T, Wieschalka S, Baican C, Baican A, Peter H, Hainzl A, Schatz S, Qi Y, Schlecht A, Weiss JM, Wlaschek M, Sunderkotter C, Scharffetter-Kochanek K. An unrestrained proinflammatory M1 macrophage population induced by iron impairs wound healing in humans and mice. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011;121:985–997. doi: 10.1172/JCI44490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosas M, Thomas B, Stacey M, Gordon S, Taylor PR. The myeloid 7/4-antigen defines recently generated inflammatory macrophages and is synonymous with Ly-6B. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:169–180. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0809548. DOI jlb.0809548 [pii] 10.1189/jlb.0809548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Platt N, Gordon S. Is the class A macrophage scavenger receptor (SR-A) multifunctional? - The mouse's tale. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:649–654. doi: 10.1172/JCI13903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jozefowski S, Arredouani M, Sulahian T, Kobzik L. Disparate Regulation and Function of the Class A Scavenger Receptors SR-AI/II and MARCO. J Immunol. 2005;175:8032–8041. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jozefowski S, Kobzik L. Scavenger receptor A mediates H2O2 production and suppression of IL-12 release in murine macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:1066–1074. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cotena A, Gordon S, Platt N. The class A macrophage scavenger receptor attenuates CXC chemokine production and the early infiltration of neutrophils in sterile peritonitis. J Immunol. 2004;173:6427–6432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.6427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Becker M, Cotena A, Gordon S, Platt N. Expression of the class A macrophage scavenger receptor on specific subpopulations of murine dendritic cells limits their endotoxin response. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:950–960. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu X, Yi H, Guo C, Zuo D, Wang Y, Kim HL, Subjeck JR, Wang XY. Pattern Recognition Scavenger Receptor CD204 Attenuates Toll-like Receptor 4-induced NF-{kappa}B Activation by Directly Inhibiting Ubiquitination of Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor-associated Factor 6. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:18795–18806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.224345. DOI M111.224345 [pii] 10.1074/jbc.M111.224345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh N, Bhatia S, Abraham R, Basu SK, George A, Bal V, Rath S. Modulation of T cell cytokine profiles and peptide-MHC complex availability in vivo by delivery to scavenger receptors via antigen maleylation. J Immunol. 1998;160:4869–4880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lu HT, Yang DD, Wysk M, Gatti E, Mellman I, Davis RJ, Flavell RA. Defective IL-12 production in mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase 3 (Mkk3)-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1999;18:1845–1857. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1845. DOI 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davies CC, Mak TW, Young LS, Eliopoulos AG. TRAF6 is required for TRAF2-dependent CD40 signal transduction in nonhemopoietic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9806–9819. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9806-9819.2005. DOI 25/22/9806 [pii] 10.1128/MCB.25.22.9806-9819.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mukundan L, Bishop GA, Head KZ, Zhang L, Wahl LM, Suttles J. TNF receptor-associated factor 6 is an essential mediator of CD40-activated proinflammatory pathways in monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174:1081–1090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1081. DOI 174/2/1081 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lutgens E, Lievens D, Beckers L, Wijnands E, Soehnlein O, Zernecke A, Seijkens T, Engel D, Cleutjens J, Keller AM, Naik SH, Boon L, Oufella HA, Mallat Z, Ahonen CL, Noelle RJ, de Winther MP, Daemen MJ, Biessen EA, Weber C. Deficient CD40-TRAF6 signaling in leukocytes prevents atherosclerosis by skewing the immune response toward an antiinflammatory profile. J Exp Med. 2010;207:391–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091293. DOI jem.20091293 [pii] 10.1084/jem.20091293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martinez FO, Gordon S, Locati M, Mantovani A. Transcriptional Profiling of the Human Monocyte-to-Macrophage Differentiation and Polarization: New Molecules and Patterns of Gene Expression. J Immunol. 2006;177:7303–7311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fulton WB, Reeves RH, Takeya M, De Maio A. A quantitative trait Loci analysis to map genes involved in lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response: identification of macrophage scavenger receptor 1 as a candidate gene. J Immunol. 2006;176:3767–3773. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sica A, Bronte V. Altered macrophage differentiation and immune dysfunction in tumor development. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007;117:1155–1166. doi: 10.1172/JCI31422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Herber DL, Cao W, Nefedova Y, Novitskiy SV, Nagaraj S, Tyurin VA, Corzo A, Cho HI, Celis E, Lennox B, Knight SC, Padhya T, McCaffrey TV, McCaffrey JC, Antonia S, Fishman M, Ferris RL, Kagan VE, Gabrilovich DI. Lipid accumulation and dendritic cell dysfunction in cancer. Nat Med. 2010;16:880–886. doi: 10.1038/nm.2172. DOI nm.2172 [pii] 10.1038/nm.2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]