Abstract

Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) is one of the most studied neurotrophic factors for neuroprotection of the retina. A large body of evidence demonstrates that CNTF promotes rod photoreceptor survival in almost all animal models. Recent studies indicate that CNTF also promotes cone photoreceptor survival and cone outer segment regeneration in the degenerating retina and improves cone function in dogs with congenital achromotopsia. In addition, CNTF is a neuroprotective factor and an axogenesis factor for retinal ganglion cells (RGCs). This review focuses on the effects of exogenous CNTF on photoreceptors and RGCs in the mammalian retina and the potential clinical application of CNTF for retinal degenerative diseases.

Keywords: CNTF, photoreceptors, retinal ganglion cells, retinal degeneration, neuroprotection, photoreceptor plasticity

1. Introduction

Neurotrophic factors are proteins that influence the survival, proliferation, differentiation, and function of neurons and other cells in the nervous system. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) is one of the most studied neurotrophic factors in retinal degenerative disorders. It is a member of the IL-6 family of neuropoietic cytokines, which includes interleukin 6 (IL-6), IL-11, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), oncostatin M (OsM), cardiotropin 1 (CT-1), and cardiotrophin-like cytokine (CLC) (Murakami et al., 2004). CNTF initiates its signaling to the responsive cells by binding to a heterotrimeric receptor complex that consists of CNTF receptor alpha (CNTFRα), gp130, and LIF receptor beta (LIFRβ). Although inactivation of the CNTF gene results in no specific abnormalities in humans and animals (Masu et al., 1993; Takahashi et al., 1994), exogenous CNTF has been shown to affect the survival and differentiation of a variety of neurons in the nervous system (Sleeman et al., 2000). CNTF is also a myotrophic factor (Sendtner et al., 1992; Sendtner et al., 1994; Kuzis and Eckenstein, 1996). In addition, CNTF influences energy balance and is being considered as a potential therapy for obesity and related type 2 diabetes (Lambert et al., 2001; Ettinger et al., 2003; Matthews and Febbraio, 2008).

The neuroprotective effect of CNTF on rod photoreceptors was first reported by LaVail and colleagues (1992). Since then, the protective effect of CNTF has been tested and confirmed in a variety of animal models of retinal degeneration across several species, including mice (Cayouette and Gravel, 1997; Cayouette et al., 1998; LaVail et al., 1998; Liang et al., 2001a; Liang et al., 2001b; Bok et al., 2002; Schlichtenbrede et al., 2003), rats (LaVail et al., 1992; Liang et al., 2001a; Tao et al., 2002; Li et al., 2010), cats (Chong et al., 1999), and dogs (Tao et al., 2002), with an exception of the XLPRA2 dogs from an RPGR mutation, a model of early onset X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (Beltran et al., 2007). Recent studies show that CNTF also protects cone photoreceptors from degeneration (Li et al., 2010; Talcott et al., 2011), and promotes the regeneration of outer segments in degenerating cones (Li et al., 2010). In addition to photoreceptors, CNTF is neuroprotective to retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) (Mey and Thanos, 1993; Meyer-Franke et al., 1995). The consistent findings of photoreceptor and RGC protection suggest that CNTF may have therapeutic potential in the treatment of photoreceptor and RGC degenerative diseases. This review focuses on the effects of exogenous CNTF on photoreceptors and RGCs in the mammalian retina and the initial clinical application of CNTF in retinal degenerative diseases.

2. CNTF and signaling pathway

2.1. The CNTF protein

CNTF was initially identified as a factor in chick embryo extract that supported embryonic chick ciliary neurons in which one-third of the activity was from the eye (Adler et al., 1979; Varon et al., 1979). The factor was purified from chick eyes and further characterized ( Varon et al., 1979; Manthorpe et al., 1980; Barbin et al., 1984). Subsequently, CNTF was obtained from rabbit and rat sciatic nerves and sequenced (Lin et al., 1989; Stockli et al., 1989). It is a 200 amino acid residue, single chain polypeptide of ~22.7 kDa. Like most cytokines, CNTF has a tertiary structure of a four-α helix bundle (McDonald et al., 1995; Panayotatos et al., 1995). The amino acid sequence lacks a consensus sequence for secretion or glycosylation, and has only one free cysteine residue at position 17 (Sleeman et al., 2000). How exactly the protein is released from cells is not clear. It has been postulated that CNTF acts as an injury-activated factor and is released from cells under pathological conditions (Adler, 1993).

2.2. The receptor complex

The biological action of CNTF on target cells is mediated through a receptor complex of three components: CNTFRα, a specific receptor for CNTF, and two signal-transducing transmembrane subunits, LIFRβ and gp130 (Boulton et al., 1994). CNTFRα was first identified by an epitope tagging technique (Squinto et al., 1990) and subsequently cloned by “tagged-ligand panning” (Davis et al., 1991). The expression of CNTFRα is mainly observed in the nervous system and skeletal muscles (Davis et al., 1991). CNTFRα does not have transmembrane or intracellular domains and, thus, is unable to induce signal transduction directly. It anchors to the plasma membrane via a glycosylphosphatidylinositol linkage (Davis et al., 1991). Membrane bound CNTFRα can be released by phospholipase C-mediated cleavage to become a soluble receptor. Therefore, cells that express LIFRβ and gp130 do not have to express CNTFRα themselves in order to respond to CNTF. Soluble CNTFRα has been detected in cerebrospinal fluid and serum (Davis et al., 1993). Unlike CNTF, genetic ablation of CNTFRα results in severe motor neuron deficits and perinatal death, indicating its importance in the development of the nervous system (DeChiara et al., 1995).

The receptor subunits responsible for mediating CNTF signaling, LIFRβ and gp130, are shared by other members of the IL-6 family of cytokines, including LIF, CT-1, OsM, and CLC (Murphy et al., 1997; Taga and Kishimoto, 1997; Murakami et al., 2004). Gp130 was discovered in an attempt to identify the signal transducer of IL-6 (Taga et al., 1989) in which IL-6 triggers the association of the 80 kD IL-6 receptor to a 130 kD protein. This 130 kD protein was subsequently cloned and identified as an IL-6 signal transducer (Taga et al., 1989; Hibi et al., 1990). LIFRβ the other signaling subunit, was isolated by screening of a human placental cDNA expression library using radioiodinated LIF as a probe. Its transmembrane and cytoplasmic regions are closely related to those of gp130 (Gearing et al., 1991).

In vitro binding experiments indicate that CNTF first binds to CNTFRα to form a CNTF/CNTFRα complex at a 1:1 ratio. The CNTF/CNTFRα complex then recruits gp130 and subsequently induces hetero-dimerization of gp130 with LIFRβ (Stahl and Yancopoulos, 1994). A CNTF receptor complex is believed to be a hexamer, consisting of 2 CNTF, 2 CNTFRα, 1 gp130, and 1 LIFRβ (De Serio et al., 1995).

2.3. The signaling pathways

CNTF induced hetero-dimerization of gp130 with LIFRβ activates the Jak/Tyk kinases. Prior to CNTF binding, Jak/Tyk kinases are associated with LIFRβ and gp130 but are not active. The activated Jak/Tyk kinases phosphorylate tyrosine residues of the intracellular domain of gp130 (Hirano et al., 1997; Hirano et al., 2000) and LIFRβ (Tomida, 2000), which provide docking sites for signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), the main downstream effector (Leonard and O’Shea, 1998). After recruitment to the docking sites of gp130 and LIFRβ, STAT3 is phosphorylated by the Jak/Tyk kinases (Lutticken et al., 1994; Raz et al., 1994), and subsequently forms homo dimers or hetero dimers with phosphorylated STAT1, which translocate to the nucleus to influence gene transcription (Bonni et al., 1993; Heinrich et al., 1998) (Fig. 1). Binding of CNTF to receptors also activates STAT1 and the extracellular-signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway, although the exact steps leading to ERK phosphorylation are not fully understood (Meyer-Franke et al., 1995; Segal and Greenberg, 1996; Weng et al., 1999).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of CNTF signaling through STAT3. CNTF binds to the receptor complex of CNTFRα, gp130, and LIFRβ and activates JAK kinase. Activated JAK kinase phosphorylates tyrosine residues (P) of the intracellular domain of gp130 and LIF, which provide docking sites for STAT3. After STAT3 is phosphorylated at the docking sites by JAK kinase, phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) forms dimers and translocates to the nucleus to induce gene transcription.

3. CNTF and retinal development

Experiments using rod specific markers (rhodopsin, for example) showed that CNTF regulates the differentiation of rod photoreceptors in the developing retina. In studies of rat retina, CNTF appeared to inhibit the differentiation of rod photoreceptors (Kirsch et al., 1996; Ezzeddine et al., 1997; Kirsch et al., 1998; Hertle et al., 2008). Other studies however indicated that the effects on the expression of photoreceptor specific markers by CNTF were transient and had no effect on the morphological maturation of photoreceptors (Fuhrmann et al., 1998; Schulz-Key et al., 2002). Thus, the inhibition of rod differentiation observed in rat retina studies may only reflect effects of CNTF on the expression of photoreceptor specific markers and not a total blockade of rod differentiation. CNTF has been shown to suppress the expression of rhodopsin in adult rats (Wen et al., 2006) (see section 4.3.).

4. CNTF and rod photoreceptors

4.1. Neuroprotection

A large body of evidence shows that CNTF has a neuroprotective effect on rod photoreceptors. This was first discovered by LaVail and colleagues (1992) in light-induced retinal damage in rats. Albino Sprague-Dawley rats were exposed to constant light of 115–200 footcandles (1,237–2,152 lux) for 7 days to induce severe rod photoreceptor death, especially in the superior posterior region of the retina (LaVail et al., 1992). Intravitreal injection of 0.5 μg of recombinant CNTF protein 2 days before constant light exposure greatly protected rod photoreceptors from light-induced damage (LaVail et al., 1992). Subsequently, intravitreal injection of CNTF was shown to protect photoreceptors in naturally occurring genetic mouse models of retinal degeneration (LaVail et al., 1998).

Cayouette and colleagues (1997; 1998) used an adenoviral (Ad) vector to deliver CNTF cDNA to the retina in addition to CNTF protein-treatment, and demonstrated that CNTF expressed from the viral vector-delivered transgene also protected photoreceptors in r d1 mice, a naturally occurring genetic model of retinal degeneration. Studies with CNTF using adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors showed that AAV-mediated gene delivery of CNTF to the retina offers long-term protection of photoreceptors (Liang et al., 2001a; Liang et al., 2001b; Bok et al., 2002; Schlichtenbrede et al., 2003). Prolonged photoreceptor survival was also achieved by repeated intravitreal injection of CNTF in an autosomal dominant feline model of rod-cone dystrophy (Chong et al., 1999).

A novel delivery technology, encapsulated cell technology (ECT) intraocular implants, has been developed for sustained delivery of protein factors to the retina (Tao et al., 2002; Tao et al., 2006; Tao and Wen, 2007) (see section 9.4.). In the CNTF-secreting implants, human retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) cells are genetically engineered to express and secrete CNTF. The engineered cells are encapsulated in a semi-permeable polymer membrane capsule. The semi-permeable membrane allows the secreted CNTF to diffuse out of the capsule and nutrients to diffuse into the capsules. A proof of concept study showed that the continuous secretion of CNTF protein at nanogram levels from the transfected cells protected photoreceptors better than a single injection of one microgram of purified CNTF protein, indicating that sustained delivery of a low dose of CNTF offers better therapeutic effect than a bolus injection of a high dose of CNTF (Tao et al., 2002) (Fig. 2). Intravitreally placed CNTF-secreting implants also significantly protected photoreceptors in a dog model of retinal degeneration (Tao et al., 2002).

Fig. 2.

Protection of photoreceptors by CNTF. Eyes of hererozygous transgenic rats carrying the rhodopsin mutation S334ter (Liu et al., 1999) were intravitreally injected with either NTC-200 cells (parental cell line, n=6) or NTC-201 cells (CNTF secreting cell line, n=6) at postnatal day 9 (PD 9). Retinas were examined at PD 20. In the untreated (A) or NTC-200 cell (B) treated retinas, only 1–2 rows of photoreceptor nuclei remained in the outer nuclear layer (ONL, white brackets), whereas in the NTC-201 cell treated eyes, the ONL contained 5–6 row of nuclei (C). From Tao et al. (2000) (Copyright by the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology).

These findings provide evidence that CNTF promotes rod photoreceptor survival in different models of retinal degeneration across several species, and that sustained delivery of CNTF provides long-term protection of photoreceptors.

4.2. CNTF and ERGs

One unexpected finding from experiments using AAV-mediated CNTF gene delivery to the retina was that, despite the long-term protection of photoreceptor cells, the electroretinogram (ERG) amplitudes were significantly decreased in the treated retinas. This was first reported in Prph2Rd2/Rd2 mice and in transgenic rats carrying rhodopsin mutations S334ter and P23H (Liang et al., 2001a; Liang et al., 2001b). The amplitude ERG b-wave was significantly suppressed in retinas after intravitreal injection of AAV vectors carrying a CNTF transgene. This finding was subsequently confirmed in the rds+/− P216L mice when subretinal injection of AAV-CNTF induced a significant decrease in rod a- and b-waves, as well as in the cone b-wave (Bok et al., 2002). Suppression of rod a- and b-waves was also observed in wild-type mice after subretinal injection of AAV-CNTF (Schlichtenbrede et al., 2003) and in rats after injection of CNTF protein (McGill et al., 2007). The AAV-CNTF induced decrease in ERGs correlated well with the numbers of virus or amount of protein injected, suggesting that CNTF-induced decrease in ERGs is dose dependent (Buch et al., 2006; McGill et al., 2007). Since ERGs provide a measure of photoreceptor function, a decrease in ERG amplitude induced by AAV-CNTF was deemed detrimental to photoreceptors and considered as “CNTF toxicity” (Liang et al., 2001a; Liang et al., 2001b; Bok et al., 2002; Schlichtenbrede et al., 2003; Bok, 2005; Buch et al., 2006; McGill et al., 2007).

In a dose-ranging study to examine the effect of CNTF on retinal function, CNTF-secreting implants with outputs of 0, 5, or 22 ng/day, (the 22 ng/day dose showed maximum photoreceptor protection in the rcd1 dog model, Tao et al., 2002), were implanted into the eyes of normal rabbits (Bush et al., 2004). No significant difference between implanted eyes and control eyes for either the a- or b-waves was seen in the scotopic ERG responses when measured 25 days after implantation, although there was a tendency towards a larger b-wave in CNTF treated eyes under dim stimuli. The cone-driven photopic b-wave amplitude was, however, significantly reduced for dim flash intensities with 22 ng/day implants, suggesting possible dose dependence.

4.3. CNTF regulates the phototransduction machinery of rods

The influence of high-dose CNTF on ERG amplitude in the retina was further investigated by Wen and colleagues (2006), who reasoned that the CNTF-induced decrease in the rod a-wave might reflect a non-toxic change in the state of the rod photoreceptors. Recombinant CNTF protein rather than AAV-CNTF was used in the experiments to better control the dose and more importantly, to observe if the CNTF-induced changes were reversible when CNTF protein was cleared. A significant decrease in scotopic a- and b-waves was observed 6 days after injecting a high dose (10 μg/eye) of recombinant CNTF protein into the vitreous of normal rats (Fig. 3). Biochemical changes were observed along with the ERG changes: a significant decrease in rhodopsin and transducin protein was observed along with an increase in rod arrestin. In addition, the length of rod outer segments (ROS) became shorter. All of these changes returned to normal levels 3 weeks after CNTF injection, apparently when CNTF was cleared (Wen et al., 2006). Since the expression of CNTF transgene was continuous in experiments using AAV-CNTF, it was impossible to observe the recovery in the AAV-CNTF experiments ( Liang et al., 2001a; Liang et al., 2001b; Bok et al., 2002; Schlichtenbrede et al., 2003; Buch et al., 2006).

Fig. 3.

Dark-adapted ERG responses in CNTF treated rat retina. ERG waveforms at increasing stimulus intensities from top to bottom recorded from retinas treated with PBS (right eye) or CNTF (10 μg, left eye) (A). Average amplitudes of the a-wave (B, C) and the b-wave (D, E) at each intensity at 6 days (B, D) and 21 days (C, E) after treatment. CNTF induced a significant decrease in the a- and b-wave 6 days after treatment. No significant difference between CNTF- and PBS-treated eyes in either a- or b-wave was seen 21 days after injection. Solid lines in B and C are B-spline curves through the data points. Solid lines in D and E are the averaged Naka-Rushton function fits. Dashed lines indicate Vmax and k values from these fits. Data points are averages of 8 animals and error bars are ± SEM. See the original paper (Wen, et al. 2006) for details. From Wen, et al. (2006) with permission.

Findings by Wen and colleagues (2006) indicate that the CNTF-induced biochemical and morphological changes in rod photoreceptors work in unison to reduce the photoreceptor response to light. A shorter ROS contains fewer disks, hence less rhodopsin, and this reduces the photon catching capability of the rod photoreceptors. Although transducin is translocatable (Sokolov et al., 2002), reduced transducin content is consistent with the lower amount of rhodopsin and shorter ROS. The increase in arrestin would reduce the signaling from activated rhodopsin (R*). Arrestin binds to R* after R* is phosphoralyted by rhodopsin kinase and blocks the interaction of R* with transducin, thereby reducing R* signaling (Palczewski, 1994). The increase in arrestin and decrease in rhodopsin in the CNTF-treated retina dramatically increases the stoichiometry of arrestin to rhodopsin in favor of arrestin-rhodopsin binding and thereby shorten the signaling duration. The overall effect of CNTF in photoreceptors is a down-regulation of phototransduction, which is detected as a reduced ERG.

The CNTF down-regulation of phototransduction is not detrimental to photoreceptors as it is equivalent to light-induced photoreceptor plasticity (described in section 5.1.). In fact, this CNTF mediated down-regulation could potentially be beneficial to photoreceptors under degenerative pressure. In the dark, photoreceptors are depolarized and cyclic GMP gated channels are open to allow Na+ and Ca2+ ions to enter, which are pumped out by K/Na ATPase. The flow of ions in the dark forms a current known as the dark current (Hagins and Yoshikami, 1975; Hagins et al., 1975). Shorter ROS have less dark current and therefore, requires less energy to maintain. In addition, as ROS is renewed at about 10% a day (described in section 5.1.), less energy and resources are needed for the renewal of shorter ROS. In cases of degeneration caused by rhodopsin mutations, the down-regulation of rhodopsin expression would reduce the mutant protein and thereby reduce the degenerative pressure. Suppression of rhodopsin expression by ribozymes has been shown to effectively protect photoreceptors in rhodopsin mutation induced degeneration (Drenser et al., 1998; Lewin et al., 1998; LaVail et al., 2000).

5. Light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity

5.1. Light-induced photoreceptor plasticity

ROS are known to undergo continuous daily renewal (Young, 1967; Young and Droz, 1968). New discs are assembled at the base of the ROS and displace the existing discs outward (Bargoot et al., 1969; Hall et al., 1969). Discs at the tip are shed and phagocytized by RPE cells (Young and Bok, 1969). In rodents, the length of ROS is regulated by the intensity of environmental light. Organisciak and Noell (1977) showed that rhodopsin content in the retina of albino rats was significantly lower in cyclic light-reared versus dark-reared animals. They concluded that ROS length depends on the light environment. Battelle and LaVail (1978) demonstrated dynamic changes in rhodopsin content and ROS length under different light conditions. They found that ROS length increased significantly when light-reared animals were moved into total darkness for 10 days. When the animals returned to their previous brighter habitat, their ROS again shortened to the previous length. Changes in environmental lighting also induce biochemical changes in the retina. When animals were moved from cyclic light to darkness, the levels of the transcripts of rhodopsin and transducin alpha increased, whereas the level of arrestin transcript decreased. These changes were reversed when the animals were moved from darkness to cyclic light (Farber et al., 1991; Organisciak et al., 1991). Similar findings were confirmed at the protein levels when animals were moved from cyclic light to total darkness (Organisciak et al., 1991).

Reiser and colleagues (1996) compared the rhodopsin content, the ROS length, and the saturated amplitude of ERG a-wave in retinas from two groups of albino rats, one reared in dim 3 lux cyclic light, and the other in 200 lux cyclic light. The rhodopsin content in the 200 lux animals was 40% less than that in the 3 lux rats. The length of ROS of the 200 lux animals was shortened to 68% of that of the 3 lux animals. Additionally, the saturated amplitude of a-wave of the 200 lux rats was reduced to 56% of that of the animals reared in the 3 lux dim light (Reiser et al., 1996). It is noteworthy that the electrophysiological changes were proportional to those in ROS length and rhodopsin content.

Penn and Williams (1986) further determined that photoreceptor plasticity extends across a range from 3 to 400 lux and found that for those intensities the retina can maintain a constant photon-catching capability. That is, ROS length is adjusted in response to the intensity of habitat light so that photoreceptors in a retina collectively catch 1.10±0.2 × 1016 photons/retina/day (Penn and Williams, 1986). They formulated this as the “photostasis hypothesis” and believed that the continuous renewal allows ROS length to be adjusted so that a retina can capture the same number of photons when the habitat illumination fluctuates.

Many fundamental questions regarding this phenomenon remain to be answered, and the regulatory mechanisms of ROS length are not fully understood. It is not clear how the number of photons captured by the entire retina is counted and how the information is fed back to individual photoreceptors so they can adjust their phototransduction machinery accordingly. Even the location of the regulatory mechanism, i.e. whether it is in the retina or is outside of the retina (for example, in the brain), had not been previously established. It is now evident that there is a mechanism inside the retina that regulates CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity as CNTF only induces changes in photoreceptors in the injected eyes, not in the contralateral eyes (Wen et al., 2006). If the light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity share a regulatory mechanism, then the location of the regulatory mechanism should be within the retina.

5.2. Does the same underlying mechanism regulate light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity?

The striking similarity between light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity raises the question of whether the same underlying mechanism regulates both light- and CNTF-induced plasticity (Fig. 4) (Wen et al., 2008). In rodents, intravitreal injection of CNTF induces a significant increase in STAT3 phosphorylation, which is localized in Müller cells and RGCs, but not in photoreceptors (Peterson et al., 2000; Wen et al., 2006). This finding leads to the conclusion that at least in rodents, Müller cells are directly responsive to CNTF (see section 8), and mediate the effects of CNTF on photoreceptors (Wen et al., 2008).

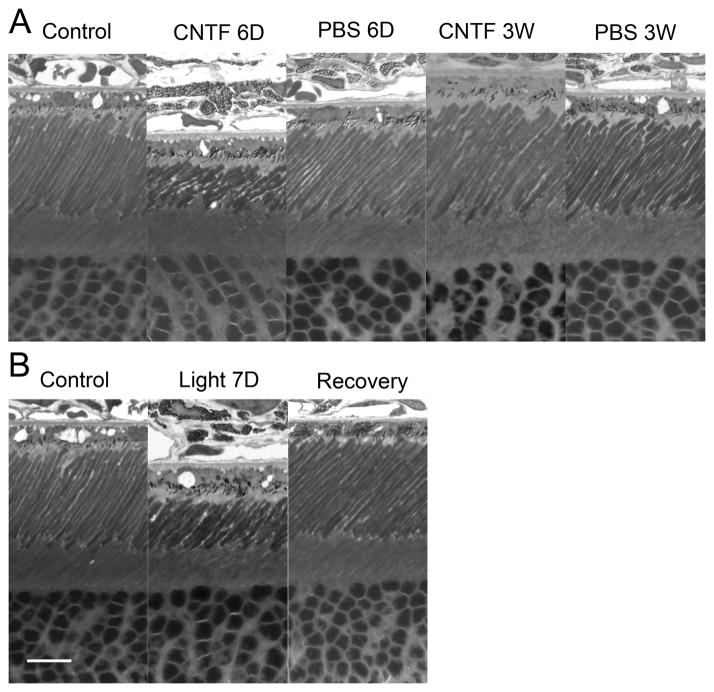

Fig. 4.

Changes of ROS induced by CNTF and light exposure. A significant shortening of the ROS were seen in eyes 6 days after CNTF treatment (A). These changes were completely reversed 3 weeks after CNTF treatment (A). No alteration of ROS was observed in eyes treated with PBS (A). A shortening of ROS was observed in eyes after 7 days of light exposure (400 lux, 10hr daily) (B). The ROS length recovered to normal after 7 days in cyclic 50 lux light (B). Scale bar: 10 μm. Modified from Wen et al. (2008).

Müller cells are radial glial cells in the retina that span almost the entire extent of the retina, from the external limiting membrane to the inner limiting membrane (Newman and Reichenbach, 1996). They are in the position to integrate information from photoreceptors to assess the number of photons they capture, and circadian information from photosensitive RGCs (Berson et al., 2002; Hattar et al., 2002).

Wen and colleagues (2008) have proposed a model of the regulatory mechanism for both the light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity. They postulate that Müller cells not only collect information of the overall number of photons received by photoreceptors as a whole along with circadian information from photosensitive RGCs, but they also integrate the information gathered and then instruct photoreceptors to adjust their outer segments accordingly (Fig. 5). The potential role of Müller cells in regulating the phototransduction in photoreceptors highlights the importance of glia-neuron interaction in regulating neuronal activities. More work is needed to reveal the cellular and molecular details of the regulatory mechanism (see Section 12).

Fig. 5.

Schematic illustration of hypothesized mechanism of CNTF- and light-induced photoreceptor plasticity. Exogenous CNTF directly activates Müller cells, which in turn signal rod photoreceptors to down-regulate the phototransduction machinery. In photostasis, Müller cells collect information of the overall number of photons captured by photoreceptors along with circadian information from photosensitive ganglion cells. When the number of photons captured exceeds the daily quota for the retina, Müller cells inform rods to down regulate their phototransduction machinery. The CNTF and photostasis pathways converge in Müller cells. From Wen et al. (2008).

6. CNTF and cone photoreceptors

Most studies of photoreceptor neuroprotection by CNTF have used rod dominant animals in which the effect of CNTF on cone photoreceptors has not been investigated. A critical piece of information about the neurotrophic effect of CNTF on cone photoreceptors came from a small phase 1 open-label clinical trial of CNTF-secreting implants in patients with advanced retinitis pigmentosa (RP) (Sieving et al., 2006). The trial was planned to determine the safety of the CNTF-implants and the surgical procedure. Surprisingly, a significant increase in visual acuity was experienced by several patients. (Sieving et al., 2006) (see section 6.2 and 11). Since few if any rods remain in the retinas of patients with advanced RP, the improvement in visual acuity is likely to have resulted from improved cone function.

6.1. Cone outer segments regeneration stimulated by CNTF

To investigate the potential neurotrophic effects of CNTF on cone photoreceptors, Li and colleagues (2010) characterized secondary cone degeneration in transgenic rats carrying the murine rhodopsin mutation S334ter (line 3). These transgenic rats experience rapid rod degeneration and are widely used as a model for retinitis pigmentosa. Rod degeneration in the S334ter rats is first detected at postnatal day 8 (PD8), and peaks at PD 11–12. By PD20, most rods are lost leading to cone degeneration ( Liu et al., 1999; Li et al., 2010). Thus, S334ter rats also provide a good model for secondary cone degeneration following rod degeneration.

In the experiments, Li and colleagues (2010) identified cone outer segments (COS) by peanut agglutinin (PNA) labeling or by antibodies against cone opsins. In addition, antibodies against cone arrestin were used to identify the cell bodies of cone photoreceptors. Loss of COS, an early sign of cone degeneration, was detected as early as PD12, at the peak of rod degeneration (Li, 2010). The loss of COS was not evenly distributed. Rather, it was concentrated in numerous small patches that were negatively stained for PNA. The PNA-negative areas expanded with age, indicating progressive loss of COS (Li et al., 2010). Intravitreal injection of recombinant CNTF protein dramatically changed the PNA-negative areas. They became significantly smaller and in many cases completely resolved. The reappearance of PNA staining in the previous PNA-negative areas suggests regeneration of COS.

To prove that CNTF treatment induces regeneration of COS, the investigators compared the COS densities before and after CNTF treatment. They demonstrated that COS density was greater in CNTF treated retina than before the treatment, confirming that CNTF treatment did promote regeneration of COS (Fig. 6). Since loss of COS is an early sign of cone degeneration, regeneration of COS could be considered as reversal of the degenerative process. This result indicates that CNTF treatment may not only slow or stop degeneration, but may also reverse the degeneration process. Given that COS is part of the functional organelles of cone photoreceptors for light detection, the regeneration of COS could translate into functional improvement of cones.

Fig. 6.

Regeneration of COS induced by CNTF treatment. Retinas (superior regions) of S334ter-3 rats at PD 35 were treated with either CNTF or PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) and harvested 10 days after treatment. Whole-mounted retinas of PD 35 (A, before treatment), PD 45 treated with PBS at PD 35 (B), and PD 45 treated with CNTF at PD 35 (C) were stained with PNA. More PNA-positive cells were seen in CNTF treated retinas than those in either PBS treated retinas or PD 35 untreated retinas. Quantitative analysis showed that PNA-positive cells were significantly more in the PD 45 CNTF treated retinas (657±76, n=4) than in the PD 35 retinas (467±73, n=3), or PD 45 retinas treated with PBS (334±33, n=3) (D, mean ± SD). Asterisk indicates P<0.05; double-asterisk indicates P ≤0.01 (ANOVA analysis and Bonferroni test). Scale bar: 100 μm. From Li et al. (2010).

In another experiment, significant long-term protection of cone cells and cone ERG were achieved by using CNTF-secreting implants for sustained delivery of CNTF to the retina of S334ter rats (Li et al., 2010).

6.2. Protection of cones in human by CNTF

As already described (section 6), the first indication of a neurotrophic effect of CNTF on cones came from a small open-label clinical trial of CNTF-secreting implants in patients with advanced RP (Sieving et al., 2006). Although the trial objective was to determine the safety of the CNTF-implants and the surgical procedure, the results showed that three patients experienced an increase of 10–15 letters over baseline in visual acuity whereas no increase was observed in the untreated fellow eyes among the seven study eyes that could be tracked for visual acuity (Sieving et al., 2006). The improvement of visual acuity is likely to have resulted from the improvement of cone function, since visual acuity tests the function of the fovea, which has only cones, and in patients with advanced RP, almost all rod photoreceptors have degenerated (see section 11).

The protective effect of CNTF on cone photoreceptors was objectively demonstrated in human patients using a powerful imaging technology known as the adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (AOSLO). Talcott and colleagues (2011) observed cones in three patients over a 2 year period and found a progressive cone density decreased in sham-treated eyes. However, the cone density remained stable in CNTF-treated eyes (see section 11). In addition, a recent clinical trial of CNTF-secreting implants in patients with geographic atrophy (GA) showed a stabilization of visual acuity in eyes treated with high dose CNTF-secreting implants (Zhang et al., 2011) (see section 11). Together, these findings indicate that CNTF is neuroprotective for cone photoreceptors.

6.3. Restoration of cone function in dogs with CNGB3 mutations by CNTF

Komáromy and colleagues (A.M. Komáromy, personal communication) recently found that a single intravitreal injection of recombinant CNTF protein in adult dogs with CNGB3 mutations, which causes day-blindness in dogs (Sidjanin et al., 2002; Komáromy et al., 2010), induced a transient restoration of cone function (as measured by ERG) and vision (as measured by behavior test). The cone ERGs became detectable for up to 4 weeks after injection. The treated animals also showed improved performance in navigating an obstacle course in bright light, indicating restoration of cone vision. There was additionally a transient decrease in rod ERG, which is consistent with the previous findings in rat and mice (see section 4.2 and 4.3). There is no functional β subunit of the cone cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channel in CNGB3 dogs and the mechanism of the restored cone function is unknown. The transient nature of these changes is likely due to the clearance of the injected CNTF protein.

7. CNTF and retinal ganglion cells

7.1. Neuroprotection

CNTF serves a neurotrophic function for RGCs. A single injection of CNTF protein (100~200 ng) into the vitreous significantly protected RGCs in an optic nerve axotomy rat model, whereas brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) did not (Mey and Thanos, 1993). RGC protection by CNTF was also seen in nitric oxide induced cell death (Takahata et al., 2003). CNTF treatment 2 days prior to injection of the nitric oxide donor significantly protected RGCs from cell death (Takahata et al., 2003). In culture, CNTF promoted the survival of purified rat RGCs in the presence of forskolin (Meyer-Franke et al., 1995).

CNTF gene transfer via Ad vectors also protects retinal ganglion cells from degeneration. RGC density in the eyes treated with intravitreal Ad-CNTF 1–2 hours after optic nerve axotomy was significantly higher than in the controls when examined 14 days later (Weise et al., 2000). Similar protection of RGCs by intravitreal injection of Ad-CNTF was reported 7, 14, and 21 days after optic nerve axotomy (van Adel et al., 2005).

Long-term CNTF delivery was achieved by lentiviral (LV) or AAV vector-mediated CNTF gene transfer. Significant RGC survival was observed on day 14 and 21 after intravitreal injection of LV-CNTF at the time of optic nerve transaction (van Adel et al., 2003). Long-term survival of RGCs after optic nerve crush or crush plus ischemia was also observed in experiments with AAV-CNTF (Leaver et al., 2006; MacLaren et al., 2006). The number of RGCs in the treated retinas was four times greater than those in the control retinas when RGCs were counted 7 weeks after optic nerve crush (Leaver et al., 2006). In experiments with optic nerve crush plus ischemia, the RGC survival in AAV-CNTF treated retinas was almost 6 times greater than in controls (MacLaren et al., 2006). A study using AAV-CNTF in laser-induced glaucoma in rats demonstrated that the loss of ganglion cell axons was much lower in treated retinas than in controls (Pease et al., 2009). A recent study showed that in an optic nerve transaction rat model, delivery of AAV-CNTF in combination with CNTF protein and CPT-cAMP (a cAMP analogue) after transaction offered greater RCG protection and axon regeneration than administration of AAV-CNTF or CNTF protein plus CPT-cAMP alone (Hellstrom et al., 2011). The injection of CNTF protein plus CPT-cAMP provides immediate protection to the RCGs whereas the AAV-CNTF, with a delay in the transgene expression, provides long-term protection.

7.2. Axogenesis

CNTF is additionally an axogenesis factor. In the presence of CNTF in a serum-free medium, purified rat RGCs showed extensive long neurite outgrowth (Jo et al., 1999; Leibinger et al., 2009). CNTF treatment also promotes axon regeneration in vivo. Enhanced RGC axon regeneration into peripheral nerve grafts after axotomy occurs with intravitreal CNTF injection in hamsters (Cui et al., 1999), mice (Cui and Harvey, 2000), and rats (Cui et al., 2003). CNTF-secreting Schwann cells carrying lentiviral-mediated CNTF cDNA were used to reconstruct peripheral nerve grafts by seeding them to peripheral nerve sheaths. Such grafts induced significant increase in survival and axonal regeneration in rat RGCs when sutured to the proximal stumps after optic nerve transaction (Hu et al., 2005). Furthermore, endogenous CNTF has been shown to be one of the key factors that mediate lens injury induced axon regeneration (Muller et al., 2009). Using CNTF knock-out and CNTF/LIF double knock-out mice, Leibinger and colleagues (2009) demonstrated that lens injury-induced axon regeneration and neuroprotection after optic nerve crush depend on endogenous CNTF and LIF. In the study discussed in section 7.1, delivery of AAV-CNTF in combination with CNTF protein and CPT-cAMP after optic nerve transaction also resulted in greater RCG axon regeneration than AAV-CNTF or CNTF protein plus CPT-cAMP alone (Hellstrom et al., 2011).

The findings that intravitreal injection of CNTF induces phosphorylation of STAT3 in RGCs (Peterson et al., 2000), and that CNTF protects RGCs (Meyer-Franke et al., 1995) and promotes neurite outgrowth in culture RGCs (Jo et al., 1999; Leibinger et al., 2009) indicate that CNTF acts directly on RGCs. A study in the optic nerve crush model showed that CNTF stimulated axon regeneration is greatly enhanced when the SOCS3 gene is deleted in RGCs (Smith et al., 2009), providing additional evidence that CNTF directly acts on RGCs.

These experiments, indicating that CNTF promotes the survival of RGCs and also stimulates axon regeneration, provide experimental evidence for considering the clinical application of CNTF for ganglion cell degeneration, such as in glaucoma, retinal ischemia, and other optic nerve injuries.

8. CNTF and RPE cells

The effects of CNTF on the RPE cells have recently been studied by Li and colleagues (2011). Using primary cultures of human fetal RPE cells that were physiologically and molecularly similar to native human tissue, they confirmed that all three receptor subunits for CNTF binding, CNTFRα, gp130, and LIFβ, are present on the apical membrane of RPE cells and that CNTF administration induces a significant increase in STAT3 phosphorylation. An important finding in the study was that CNTF significantly increases the active ion-linked fluid absorption across the RPE through cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), which is specifically blocked by an CFTR inhibitor (Li et al., 2011). In addition, administration of CNTF increases the survival of RPE cells and modulates the secretion of several neurotrophic factors and cytokines from the apical side, including an increase in NT3 (neurotrophin3, Kalb, 2005) secretion, and decreases in VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor), TGFβ2 (transforming growth factor-β2), and IL-8 secretion (Li et al., 2011). The increase in RPE cell survival observed in this study is consistent with the previous finding in rat RPE cells, in which significant increase in cell survival was seen in primary culture of rat RPE cells and an immortalized rat cell line BPEI-1 in the presence of CNTF or LIF (1–50 ng/mL) (Gupta et al., 1997).

RPE is a monolayer of polarized epithelial cells located between the neuronal retina and the choroidal blood supply, an important component of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) (Cunha-Vaz, 1976). Ions, fluid, nutrients, and metabolic waste products are selectively transported between the neuronal retina and the choriocapillaris (Adijanto et al., 2009). The increase in fluid transport from the apical to the basal side suggests that in addition to neuroprotection, CNTF may help to reduce retinal edema, and aid reattachment of the retina to the RPE in retinal detachment by pumping more fluid from the retina to the choriod. The increase in RPE cell survival in the presence of CNTF could stabilize the RPE loss in geographic atrophy (GA) in addition to photoreceptor protection, as RPE atrophy is considered a contributing factor in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) (Zarbin, 2004). This is consistent with the results in a recent clinical trial of CNTF-secreting implants in patients with geographic atrophy in which CNTF treatment was shown to stabilize visual acuity (Zhang et al., 2011). The RPE study provides valuable information further studies in vivo to investigate how CNTF changes RPE behaviors.

9. CNTF responsive cells in the retina

It is difficult to identify CNTF responsive cells simply by localizing the expression of its receptors: CNTFRα, LIFRβ, and gp130. The presence of soluble CNTFRα means that it is not necessary for cells to express CNTFRα to respond to CNTF. In addition, the receptors, LIFRβ and gp130, are shared by other members of the IL-6 family of cytokines. Therefore, to identify CNTF responsive cells, a reliable method is to identify cells in which the downstream effector STAT3 is phosphorylated in response to CNTF. The availability of antibodies specifically for pSTAT3 makes such localization feasible by immunocytochemistry. Intravitreal injection of Axokine, a CNTF analog, has been shown to induce pSTAT3 predominately in the nuclei of Müller cells, RGCs, and astrocytes, but not in photoreceptors (Peterson et al., 2000). Similar results were observed in retinas treated with recombinant CNTF protein in which an increase in pSTAT3 was mainly seen in Müller cells, and none was detected in photoreceptor nuclei (Wen et al., 2006) (Fig. 7). In a study using recombinant human CT-1, increases in pSTAT3 were located in the nuclei of Müller cells and RGCs, but not in the outer nuclear layer where photoreceptor nuclei reside (Song et al., 2003). Xue and colleagues (2011) recently explored the expression profile of Müller cells after CNTF treatment in vivo. Using transgenic mice expressing green fluorescent protein, the investigators isolated Müller cells from retinas 3 days after intravitreal injection of CNTF by using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). The significant changes in expression profile in Müller cells after CNTF treatment provide additional evidence that Müller cells are responsive to CNTF.

Fig. 7.

CNTF-induced phosphorylation of STAT3. Immunostaining of phospho-STAT3 was mainly detected in the nuclei of ganglion cells in the untreated retina (A). CNTF induced a dramatic increase in STAT3 phosphorylation in a specific band of cells in the INL (B). Müller cells were identified by antibodies against GS (glutamine synthetase) (C, red). The immunoreactivities of pSTAT3 (green) and GS (red) are clearly co-localized (D, yellow). OS, outer segments; ONL, outer nuclear layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; GCL, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar: 50 μm. Modified from Wen et al. (2006) with permission.

These observations imply that Müller cells are the major CNTF responsive cells in the retina whereas photoreceptors are not responsive to CNTF. Therefore, the effects of CNTF on photoreceptors are likely mediated by other cells, including Müller cells. As the major glial cells in the retina, Müller cells span the entire thickness of the retina and are in close contact with photoreceptors (Newman and Reichenbach, 1996). The finding that CNTF induced STAT3 phosphorylation is present in the Müller cells but absent in the photoreceptors supports the central role of Müller cells in the regulatory mechanism for both light- and CNTF-induced photoreceptor plasticity (Wen et al., 2008) (see section 5.2).

Studies in other species, however, suggest that photoreceptors may also be responsive to CNTF. Expression of CNTFRα has been observed in photoreceptors in mice, rats, dogs, cats, pigs, and humans (Beltran et al., 2005; Hertle et al., 2008), indicating that these photoreceptors are capable of responding to CNTF directly. In addition, genetic ablation of gp130 in mouse photoreceptors renders them more susceptible to light induced damage, signifying that gp130 mediated signaling in photoreceptors is important in protecting photoreceptors through endogenous factors (Ueki et al., 2009).

10. Delivery of CNTF to the retina

10.1. Systemic administration

Preclinical studies in animal models of photoreceptor degeneration strongly indicate that long-term neuroprotection is achievable with sustained delivery of CNTF. The challenge is how to effectively and sustainably deliver CNTF to the retina. The existence of the blood-retinal barrier (BRB) (Cunha-Vaz, 1976) makes it difficult for systemically-administered large molecules, such as CNTF, to reach the retina. In addition, CNTF protein is quickly removed from the blood stream when administered by intravenous or subcutaneous injection. A pharmacokinetic study showed a biphasic clearance of intravenously injected CNTF with an initial plasma half-life of 2.9 minutes and a slower second phase with a half-life of 4 hours in rat. About 75% of CNTF was removed from circulation in 10 minutes (Dittrich et al., 1994). In a human study, plasma CNTF concentration was monitored after a single subcutaneous injection of recombinant human CNTF. Peak plasma CNTF concentration was reached at 180 to 260 minutes, followed by a declining phase with an elimination half-life of 120–400 minutes (The ALS CNTF Treatment Study (ACTS) Phase I-II Study Group, 1995a). Systemic administration of CNTF also has the potential to trigger undesirable effects, including elevated temperature, cough, asthenia, nausea, anorexia, weight loss, aphthous stomatitis, and an increase in C-reactive protein (The ALS CNTF Treatment Study (ACTS) Phase I-II Study Group, 1995b; The ALS CNTF Treatment Study Group, 1996). Thus, systemic administration is not a practical route of delivery CNTF protein to the retina.

10.2. Intravitreal injection

Purified recombinant CNTF protein can be delivered to the retina by intraocular injection, but this route is not feasible for long-term clinical delivery. The effect of CNTF lasts less than 3 weeks after a single intravitreal injection of a large amount of CNTF protein (10 μg for a rat eye) (Wen et al., 2006). The chronic nature of retinal degeneration, the short half-life of CNTF, and the invasive nature of repeated intraocular injection make this approach clinically undesirable.

10.3. Viral vector approach

CNTF transgene delivered by AAV or LV vectors could achieve sustained secretion of CNTF by transduced retinal cells. Protection of photoreceptors has been demonstrated by viral vector delivered CNTF transgene in animal models of retinal degeneration (see section 4.1, 7.1 and 7.2). However, several issues make the clinical potential of this approach questionable. Precise control of the CNTF dosage has yet to be achieved for clinical application with viral vectors. The difficulty lies not only on the selection of promoters, which determine the target cell types and the levels of expression, but also on the number of cells transduced. Further issues are the adjustment of CNTF output according to the disease situation and the termination of treatment if necessary. Neither is achievable clinically with the current technology.

10.4. Encapsulated cell technology and CNTF secreting implants

Encapsulated cell technology enables controlled and sustained delivery of CNTF to the vitreous and the retina. A CNTF-secreting ECT intraocular implant has been developed by Neurotech USA for sustained delivery of CNTF to the retina (designated NT-501) (Tao et al., 2002). The NT-501 implants are small capsules of hollow fiber membrane in which live human RPE cells engineered to secrete CNTF (NTC-201 cells) are encapsulated. The physical characteristics of the membrane allows for the outward diffusion of therapeutics (CNTF in this case) and other cellular metabolites and the inward diffusion of nutrients necessary to support cell survival. In addition, the cells in the implants are protected from rejection by the host immune system (Fig. 8) (Tao, 2006; Tao et al., 2006; Tao and Wen, 2007).

Fig. 8.

Schematic illustration of CNTF-secreting implant using Encapsulated Cell Technology. The implant is composed of a section of semi-permeable membrane capsule which contains CNTF secreting cells and scaffold. The membrane capsule is sealed at both ends with a suture clip at one end for anchoring on the sclera (A). The membrane allows O2 and nutrients to diffuse in and therapeutic agent (CNTF in this case) to diffuse out. It also keeps components of the immune system out (B). The implant is 6 mm in length and 1 mm in diameter. It is outside the visual axis of the eye when anchored to the sclera (C).

ECT implants are currently the best option for sustained delivery of protein factors to the retina, especially considering the limited distribution volume of the vitreous, easy capsule delivery into the eye, and the chronic nature of the diseases to be targeted. The therapeutic protein is synthesized and released in situ. The implants are capable of secreting protein continuously for more than two years, the longest time tested to date (W. Tao, unpublished observations). The ECT implant can be engineered to achieve the optimal dose for treatment. Treatment can be terminated if necessary by simply retrieving the implant.

11. Clinical studies of CNTF for retinal degenerative disorders

A clinical development program involving CNTF-secreting ECT implants in the treatment of retinal degenerative disorders has already been initiated. A Phase 1 open-label clinical trial of CNTF-secreting ECT implants involving ten patients has been completed (Sieving et al., 2006). The participants had advanced RP with a component of atrophic macular degeneration that reduced visual acuity. Five subjects received lower dose implants and the remaining five received higher dose implants that delivered 5-fold higher dose of CNTF than the lower dose implants. The implants were well tolerated, indicating the safety and promising utility of ECT delivery as a mode of administration of protein therapeutics to the eye. In addition, improvement of visual acuity was observed in a few treated eyes. One participant, who could not read any letters at baseline, gained 20 letters within seven months after receiving the implant and maintained a 15-letter gain for six months after the implant removal. The improvement of vision in some eyes during CNTF treatment suggests improved cone function, which is consistent with experimental findings that CNTF promotes regeneration of cone outer segments in the rat retina (Li et al., 2010).

A phase 2 study of CNTF-secreting implants in patients with dry AMD (GA) has also been completed (Zhang et al., 2011). The primary endpoint of this multicenter, 1-year, double-masked, sham-controlled dose-ranging study was the change in best corrected visual acuity. All eyes with best corrected visual acuity at 20/63 and better in the high-dose group had minimal loss of less than 15 letters, as compared with the combined group of eyes treated with low-dose implants and sham operation, in which only 55.6% lost less than 15 letters. (Fig. 9) (Zhang et al., 2011). In addition, an increase in retinal thickness was found in association with visual function stabilization (see section 12.5). These findings are consistent with results from the Phase 1 trial and animal models that indicate CNTF protects cone photoreceptors.

Fig. 9.

Effect of intraocular CNTF on visual acuity stabilization. Fifty-one patients with geographic atrophy were randomly treated with high- or low-dose CNTF implants or sham operated. As measured at 12 months post implantation, 96.3% of the high-dose eyes lost <3 lines (<15 letters), whereas 75% of sham treated eyes lost <15 letters (P=0.078) (A). For patients with baseline vision at 20/63 or better, 100% in the high-dose group lost <15 letters whereas 55.6% in the combined low-dose/sham group lost < 15 letters, (P=0.033). Modified from Zhang et al. (2011).

AOSLO is a technology that enables direct observation of cone cells en face in the retina of patients. Using this imaging technology, Talcott and colleagues (2011) monitored cone density in three patients (two with RP and one with Usher Syndrome Type 2) over a 2-year period. In each patient, one eye was sham-treated and the other was implanted with a CNTF-secreting implant. During the two year interval, a decrease in cone density of 9–24% in 8 of 9 parafoveal locations sampled in sham-treated eyes was observed. However, in the CNTF-treated eyes, the cone density remained stable in all 12 locations studied. The difference between CNTF and sham-treated eyes is remarkable and indicates a protective effect of CNTF on cone cells in human patients (Talcott et al., 2011). No significant changes in visual acuity, visual field sensitivity, or ERG responses were observed in the 2-year period.

These three clinical studies provide strong evidence that CNTF, delivered by CNTF-secreting implants, protects cone photoreceptors in humans.

12. Future directions

12.1. To understand the mechanism of CNTF induced ne uroprotection

The consistent finding that CNTF protects photoreceptors in almost all animal models across several species indicates that the mechanisms mediating CNTF-induced photoreceptor protection appears to be retained across species in the mammalian retina. Since CNTF protects photoreceptors in different models with a variety of genetic or environmental causes, it is considered a “broad spectrum” photoreceptor protective agent. However, evidence relating to the mechanisms that mediate the protective effects of CNTF is not well established compared to the large body of work confirming the neuroprotective effect of CNTF on photoreceptors and RGCs. Thus, the next challenge to the research community is to understand the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying CNTF-induced neuroprotection.

For RGCs, it is quite clear from published data that CNTF acts on RGCs directly. In the case of photoreceptors, however, the picture is not very clear. Consistent findings in rodents indicate that photoreceptors are not responsive directly to exogenous CNTF. Therefore, the effects on photoreceptors, at least in rodents, must be mediated through other cells that are responsive directly to CNTF. Data from experiments in rodents suggest that Müller cells could be the mediator (see section 11.2). Further experiments to provide definitive evidence of Müller cell involvement in mediating the protective effect of CNTF will be crucial to understanding the mechanism of CNTF protection of photoreceptors.

12.2. The Müller-photoreceptor interaction: a key to understanding light-induced photoreceptor plasticity?

In addition to its neuroprotective effects on photoreceptors and RGCs, CNTF induces a down-regulation of rod phototransduction machinery very similar to the effects of ambient light. A common mechanism is believed to underlie the two phenomena (Wen et al., 2006; Wen et al., 2008) (see section 5.2). Although light-induced photoreceptor plasticity was discovered more than 30 years ago, the underlying mechanism is still not fully understood. CNTF, therefore, provides a valuable tool for exploring this mechanism.

As discussed above (see section 9), CNTF treatment induces an increase in phosphorylation of STAT3 in Müller cells, not in photoreceptors, yet a dramatic change in photoreceptors is induced by CNTF. This consistent finding indicates that photoreceptors are not directly responsive to CNTF, and the changes in photoreceptors are mediated by cells that are directly activated by CNTF, likely Müller cells. The model presented in Figure 5 proposes that Müller cells play a central role in mediating both CNTF- and light-induced photoreceptor plasticity. Thus, identifying the Müller-photoreceptor interaction may be a key to understanding light-induced photoreceptor plasticity.

Understanding the role Müller cells play in mediating CNTF induced photoreceptor plasticity would provide crucial information not only for the clinical development of CNTF in retinal degenerative disorders, but also potentially for development of second generation treatments with improved efficacy and deliverability. In addition, it would lead to a better understanding of the information feedback loop between photoreceptors and Müller cells to fine tune the phototransduction machinery in response to the changing environmental lighting.

12.3. What is the advantage of photostasis?

The continuous renewal of photoreceptor outer segments entails a great cost in energy and resource consumption. In the mouse, the complete renewal of ROS takes about 10 days (Young, 1983). A rod outer segment in the mouse is estimated to have 810±33 discs (Liang et al., 2004). So in the mouse retina, a rod produces about 80 new disks to make up the 10% outer segment shed each and every day throughout its life in order to maintain the proper length of the outer segment. The 80 new discs contain a total of 6.4 × 106 opsin molecules or about 0.37 pg opsin (based on molecular weight of 34 kD), given that in mouse each disk contains about 8 × 104 rhodopsin molecules (Palczewski, 2006). In addition, rod cells have to synthesize a large amount of lipid bilayer to assembly the new discs. The surface area of a single disc membrane in a mouse rod is measured to be 1.27 μm2 (Nickell et al., 2007). That means a rod cell has to synthesize more than 200 μm2 of membrane for the 80 new discs each day, twice as much as the entire surface area of a rod outer segment, which is close to 100 μm2, given the average length of 23.8±1.0 μm and diameter of 1.32±0.12 μm in a rod outer segment in a mouse (Nickell et al., 2007)

What is the purpose of the ongoing renewal of the outer segments that demands such a high cost of energy and resources? Penn and Williams (1986) have proposed the photostasis hypothesis to explain the constant ROS renewal. They suggest that the renewal of outer segments provides a mechanism to adjust the ROS length in response to the changing ambient lighting for a retina to capture the same number of photons each day over a wide range of light intensities (see section 5.1). But what are the evolutionary advantages of photostasis?

We believe that photostasis has developed to maintain an optimal condition for the retinal circuitry to process information in the changing ambient lighting. The retina does a great amount of image processing in the inner retina to extract important information (Field and Chichilnisky, 2007). When the background (ambient) lighting changes, it could affect the efficiency and capability of the retinal information processing. It seems that in order to maintain the optimal working condition to the retinal circuitry, evolution has developed a mechanism to adjust the “sensitivity” of photoreceptors to accommodate the fluctuation of environmental light so that the background lighting appears to be constant to the retina. In that way, the retina can work at a relatively stable and perhaps optimal condition, at the set-point of photostasis, to extract critical information to allow an animal to find food and to avoid predators. Such adjustment of retinal “sensitivity” may be likened to choosing the sensitivity of film (the “film speed” or the ISO number, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Photographic_film) in photography to achieve optimal exposure and contrast under different lighting conditions.

12.4. To explore the mechanism of CNTF-induced improvement of cone function in dogs with CNGB3 mutations

CNTF treatment improves cone function in dogs with CNGB3 mutations (section 6.3). However, the mechanism of action is not clear. The mutant dogs lack the β subunits, the modulatory subunits, of the cone CNG channels, (Gerstner et al., 2000). In the absence of the β subunits, how does CNTF treatment improve the function of the channels?

It has been shown that the α subunits can form homo-tetramer functional channels without the presence of the β subunits. Expressing human CNGA3 (the gene encoding the α subunits cone CNG channels) in Xenopus oocytes gave rise to cGMP-stimulated currents (Wissinger et al., 1997). In addition, residual cone activity was observed in the CNGB3−/− mice in which cone-driven photopic b-waves were measured to be 25–30% of the normal amplitude of wild-type mice at one month of age, and the activity remains detectable even in 18-month old CNGB3 deficient mice (Ding et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2011). The expression of CNGA3 in the CNGB3−/− mice is reduced (Ding et al., 2009; Carvalho et al., 2011), which is believed to be the pathogenic mechanism leading to cone diseases with CNGB3 mutations (Ding et al., 2009). In comparison, genetic ablation of the CNGA3 gene completely abolishes the photopic b-wave (Biel et al., 1999).

The ERG findings from dogs with CNGB3 mutations are different from CNGB3−/− mice. No residual cone-driven ERGs were detectable in mutant dogs (Komáromy et al., 2010). The expression of CNGA3 is not suppressed either. However, the α subunits were not detectable in cone outer segments (Komáromy et al., 2010). Interestingly, when the β subunits were introduced via AAV vectors, they help the α subunits to target to the outer segments (Komáromy et al., 2010). These findings are consistent with the β subunits being a critical factor for the CNG channels to traffic to the outer segments. It is known that the modulatory subunits of CNG channels are essential to promote the proper localization of the channels. In mice lacking CNGB1 (the gene encoding the β subunits of rod CGN channels), the α subunits are not detected in ROS even though the expression of CNGA1, the gene encoding for the α subunits of rod CNG channels, is detected (Huttl et al., 2005). In addition, the CNG channels lacking either the modulatory subunit CNGB1b or the CNGA4 fail to target to the cilia of olfactory receptor neurons (Michalakis et al., 2006).

Thus, in the mutant dogs, CNTF might have facilitated the α subunits to target to the cone outer segments and might have induced the assembly of α subunits homo-tetramer channels in the absence of the β subunits, resulting in an improvement in the function of cone CGN channels. In addition, CNTF might stimulate the expression of the α subunits. The possible role of CNTF in the α subunits targeting to the cone outer segments and/or in the upregulation of CNGA3 expression should be explored in future experiments.

Patients with CNGB3-associated achromatopsia have negligible or non-recordable photopic b-waves and diminished flicker responses (Khan et al., 2007; Wiszniewski et al., 2007), similar to those observed in dogs with CNGB3 mutations. The improved cone function in dogs after CNTF treatment therefore raises the hope that such treatment could restore cone function in patients with CNGB3-associated achromatopsia. Given the good safety profile of CNTF-secreting implants in clinical trials (Sieving et al., 2006; Talcott et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011), It might be feasible to investigate CNTF-secreting implants on cone function in patients with autosomal recessive achromatopsia caused by CNGB3 mutation.

12.5. Other CNTF related findings need further study

CNTF, especially in the AAV-CNTF studies cited above, also induces other changes in the retina. An increase in euchromatin and nuclear size was observed in rod photoreceptors in eyes with subretinal, but not intravitreal injected AAV-CNTF (Bok et al., 2002). In another study, AAV-CNTF treatment was shown to induce disorganization of the inner nuclear layer, including Müller and bipolar cells. It is not clear, however, whether this increase was due to AAV vector itself or CNTF, since no control AAV vector injection was included in that study (Rhee et al., 2007). In dog retinas treated with CNTF-secreting implant, an increase in the thickness in the entire retina was observed, along with morphological changes in rods and RGCs (Zeiss et al., 2006). The increase in retinal thickness after CNTF treatment was also observed in rabbits (Bush et al., 2004) and humans (Zhang et al., 2011). These observations warrant further study, as there was no increase in cell number or any evidence for a toxic effect, as shown by lack of difference in cystoid macular edema or epiretinal membrane in CNTF-treated eyes compared to sham-treated eyes (Zhang et al., 2011).

12.6. New technologies to monitor photoreceptor degeneration

Results from the CNTF clinical trials also raised an important question regarding the suitability of the current clinical evaluation techniques for objective and reliable outcome measurements. As shown by Talcott and colleagues (Talcott et al., 2011), CNTF treatment stabilized the loss of cone photoreceptors in patients over 2 years when measured by AOSLO, whereas significant loss of cone cells occurred in the sham-treated fellow eyes. However, the loss of cones was not accompanied by any detectable changes in visual function measured by conventional means, including visual acuity, visual field sensitivity, and ERG, indicating that these conventional outcome measures do not have adequate sensitivity commensurate with AOSLO structural measures (Talcott et al., 2011). Technological advances, including the availability of ultrahigh resolution optical coherence tomography, adaptive optics retinal camera, AOSLO, and scanning laser ophthalmoscope microperimetry, will no doubt accelerate our understanding of the disease progression and the development of new therapies for retinal degenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. András Komáromy for allowing us to discuss his unpublished data and for critically reading the manuscript; and Dr. Byron Lam for critically reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (R01EY12727, R01EY018586 to RW, P30EY14801 to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute), Hope for Vision (RW), the James and Esther King Biomedical Research Program of the State of Florida (YL), the Department of Defense (W81XWH-09-1-0674 to RW), an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness to Bascom Palmer Eye Institute; and by the intramural research program of National Institutes of Health, National Eye Institute, and National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Abbreviations

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- Ad

adenovirus

- AMD

age-related macular degeneration

- AOSLO

adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscopy

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- BRB

blood-retinal barrier

- CFTR

cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- CLC

cardiotrophin-like cytokine

- CNG

cyclic nucleotide-gated channel

- CNTF

ciliary neurotrophic factor

- CNTFRα

CNTF receptor alpha

- COS

cone outer segments

- CT-1

cardiotropin 1

- ECT

encapsulated cell technology

- ERG

electroretinogram

- ERK

extracellular-signal-regulated kinase

- FACS

fluorescence activated cell sorting

- GA

geographic atrophy

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- IL-8

interleukin 8

- IL-11

interleukin 11

- LIF

leukemia inhibitory factor

- LIFRβ

LIF receptor beta

- LV

lentivirus

- NT3

neurotrphin3

- OsM

oncostatin M

- PD

postnatal day

- PNA

peanut agglutinin

- pSTAT3

phosphorylated STAT3

- R*

activated rhodopsin

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- ROS

rod outer segments

- RP

retinitis pigmentosa

- RPE

retinal pigment epithelium

- STAT

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TGFβ2

transforming growth factor-β2

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adijanto J, Banzon T, Jalickee S, Wang NS, Miller SS. CO2-induced ion and fluid transport in human retinal pigment epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133:603–622. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R. Ciliary neurotrophic factor as an injury factor. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1993;3:785–789. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(93)90154-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler R, Landa KB, Manthorpe M, Varon S. Cholinergic neuronotrophic factors: intraocular distribution of trophic activity for ciliary neurons. Science. 1979;204:1434–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.451576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbin G, Manthorpe M, Varon S. Purification of the chick eye ciliary neuronotrophic factor. J Neurochem. 1984;43:1468–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1984.tb05410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bargoot FG, Williams TP, Beidler LM. The localization of radioactive amino acid taken up into the outer segments of frog (Rana pipiens) rods. Vision Res. 1969;9:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(69)90085-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battelle BA, LaVail MM. Rhodopsin content and rod outer segment length in albino rat eyes: modification by dark adaptation. Exp Eye Res. 1978;26:487–497. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(78)90134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran WA, Rohrer H, Aguirre GD. Immunolocalization of ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor alpha (CNTFRalpha) in mammalian photoreceptor cells. Mol Vis. 2005;11:232–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltran WA, Wen R, Acland GM, Aguirre GD. Intravitreal injection of ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) causes peripheral remodeling and does not prevent photoreceptor loss in canine RPGR mutant retina. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:753–771. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berson DM, Dunn FA, Takao M. Phototransduction by retinal ganglion cells that set the circadian clock. Science. 2002;295:1070–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.1067262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biel M, Seeliger M, Pfeifer A, Kohler K, Gerstner A, Ludwig A, Jaissle G, Fauser S, Zrenner E, Hofmann F. Selective loss of cone function in mice lacking the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel CNG3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7553–7557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok D. Ciliary neurotrophic factor therapy for inherited retinal diseases: pros and cons. Retina. 2005;25:S27–S28. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200512001-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bok D, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Ruiz A, Duncan JL, Chappelow AV, Zolutukhin S, Hauswirth W, LaVail MM. Effects of adeno-associated virus-vectored ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and function in mice with a P216L rds/peripherin mutation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74:719–735. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Frank DA, Schindler C, Greenberg ME. Characterization of a pathway for ciliary neurotrophic factor signaling to the nucleus. Science. 1993;262:1575–1579. doi: 10.1126/science.7504325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulton TG, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Ciliary neurotrophic factor/leukemia inhibitory factor/interleukin 6/oncostatin M family of cytokines induces tyrosine phosphorylation of a common set of proteins overlapping those induced by other cytokines and growth factors. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11648–11655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buch PK, MacLaren RE, Duran Y, Balaggan KS, MacNeil A, Schlichtenbrede FC, Smith AJ, Ali RR. In contrast to AAV-mediated Cntf expression, AAV-mediated Gdnf expression enhances gene replacement therapy in rodent models of retinal degeneration. Mol Ther. 2006;14:700–709. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush RA, Lei B, Tao W, Raz D, Chan CC, Cox TA, Santos-Muffley M, Sieving PA. Encapsulated cell-based intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor in normal rabbit: dose-dependent effects on ERG and retinal histology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2420–2430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho LS, Xu J, Pearson RA, Smith AJ, Bainbridge JW, Morris LM, Fliesler SJ, Ding XQ, Ali RR. Long-term and age-dependent restoration of visual function in a mouse model of CNGB3-associated achromatopsia following gene therapy. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3161–3175. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayouette M, Gravel C. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor can prevent photoreceptor degeneration in the retinal degeneration (rd) mouse. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8:423–430. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.4-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayouette M, Behn D, Sendtner M, Lachapelle P, Gravel C. Intraocular gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents death and increases responsiveness of rod photoreceptors in the retinal degeneration slow mouse. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9282–9293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09282.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong NH, Alexander RA, Waters L, Barnett KC, Bird AC, Luthert PJ. Repeated injections of a ciliary neurotrophic factor analogue leading to long-term photoreceptor survival in hereditary retinal degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:1298–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Harvey AR. CNTF promotes the regrowth of retinal ganglion cell axons into murine peripheral nerve grafts. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3999–4002. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200012180-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Lu Q, So KF, Yip HK. CNTF, not other trophic factors, promotes axonal regeneration of axotomized retinal ganglion cells in adult hamsters. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:760–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Yip HK, Zhao RC, So KF, Harvey AR. Intraocular elevation of cyclic AMP potentiates ciliary neurotrophic factor-induced regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cell axons. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22:49–61. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Vaz JG. The blood-retinal barriers. Doc Ophthalmol. 1976;41:287–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00146764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Aldrich TH, Valenzuela DM, Wong VV, Furth ME, Squinto SP, Yancopoulos GD. The receptor for ciliary neurotrophic factor. Science. 1991;253:59–63. doi: 10.1126/science.1648265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis S, Aldrich TH, Ip NY, Stahl N, Scherer S, Farruggella T, DiStefano PS, Curtis R, Panayotatos N, Gascan H, et al. Released form of CNTF receptor alpha component as a soluble mediator of CNTF responses. Science. 1993;259:1736–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.7681218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Serio A, Graziani R, Laufer R, Ciliberto G, Paonessa G. In vitro binding of ciliary neurotrophic factor to its receptors: evidence for the formation of an IL-6-type hexameric complex. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:795–800. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeChiara TM, Vejsada R, Poueymirou WT, Acheson A, Suri C, Conover JC, Friedman B, McClain J, Pan L, Stahl N, Ip NY, Yancopoulos GD. Mice lacking the CNTF receptor, unlike mice lacking CNTF, exhibit profound motor neuron deficits at birth. Cell. 1995;83:313–322. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding XQ, Harry CS, Umino Y, Matveev AV, Fliesler SJ, Barlow RB. Impaired cone function and cone degeneration resulting from CNGB3 deficiency: down-regulation of CNGA3 biosynthesis as a potential mechanism. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4770–4780. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittrich F, Thoenen H, Sendtner M. Ciliary neurotrophic factor: pharmacokinetics and acute-phase response in rat. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:151–163. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenser KA, Timmers AM, Hauswirth WW, Lewin AS. Ribozyme-targeted destruction of RNA associated with autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:681–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ettinger MP, Littlejohn TW, Schwartz SL, Weiss SR, McIlwain HH, Heymsfield SB, Bray GA, Roberts WG, Heyman ER, Stambler N, Heshka S, Vicary C, Guler HP. Recombinant variant of ciliary neurotrophic factor for weight loss in obese adults: a randomized, dose-ranging study. JAMA. 2003;289:1826–1832. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzeddine ZD, Yang X, DeChiara T, Yancopoulos G, Cepko CL. Postmitotic cells fated to become rod photoreceptors can be respecified by CNTF treatment of the retina. Development. 1997;124:1055–1067. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.5.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber DB, Danciger JS, Organisciak DT. Levels of mRNA encoding proteins of the cGMP cascade as a function of light environment. Exp Eye Res. 1991;53:781–786. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(91)90114-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field GD, Chichilnisky EJ. Information processing in the primate retina: circuitry and coding. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann S, Heller S, Rohrer H, Hofmann HD. A transient role for ciliary neurotrophic factor in chick photoreceptor development. J Neurobiol. 1998;37:672–683. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199812)37:4<672::aid-neu14>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing DP, Thut CJ, VandeBos T, Gimpel SD, Delaney PB, King J, Price V, Cosman D, Beckmann MP. Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor is structurally related to the IL-6 signal transducer, gp130. EMBO J. 1991;10:2839–2848. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]