Abstract

Background and Purpose

Swallowing screens after acute stroke identify those patients who do not need a formal swallowing evaluation and who can safely take food and medications by mouth. We conducted a systematic review to identify swallowing-screening protocols that met basic requirements for reliability, validity, and feasibility.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE and supplemented results with references identified through other databases, journal tables of contents, and bibliographies. All relevant references were reviewed and evaluated with specific criteria.

Results

Of 35 protocols identified, four met basic quality criteria. These four had high sensitivities of 87% or greater and high negative predictive values of 91% or greater when a formal swallowing evaluation was used as the gold standard. Two protocols had greater sample sizes and more extensive reliability testing than the others.

Conclusion

We identified only four swallowing-screening protocols for patients with acute stroke that met basic criteria. Cost effectiveness of screening--including costs associated with false positives and impact of screening on morbidity, mortality, and length of hospital stay--requires elucidation.

Keywords: dysphagia, swallowing, screening, evaluation, stroke

Introduction

Dysphagia affects 37-78% of patients with acute stroke and is associated with increased risk of aspiration, pneumonia, prolonged hospital stay, disability, and death.1 Since formal swallowing evaluation is neither possible nor warranted in all patients with acute stroke, the purpose of a swallowing screen is to identify those patients who do not need a formal evaluation and who can safely take food and medications by mouth. In this review, we addressed the following questions about swallowing screens after acute stroke: what standardized protocols have been described; how do protocols compare with respect to reliability, validity, and feasibility as defined by ease of training and administration; and what are the challenges of screening.

Methods

The search strategy and the inclusion and exclusion criteria for relevant papers so identified are detailed in the online supplement (see http://stroke.ahajournals.org). Information on study design, study size, and ease of training, administration and scoring was sought but not required for inclusion. One of the authors (SKS) conducted the search for papers and evaluated protocols with input from her co-authors. She is a former speech pathologist and current board-certified neurologist.

Results

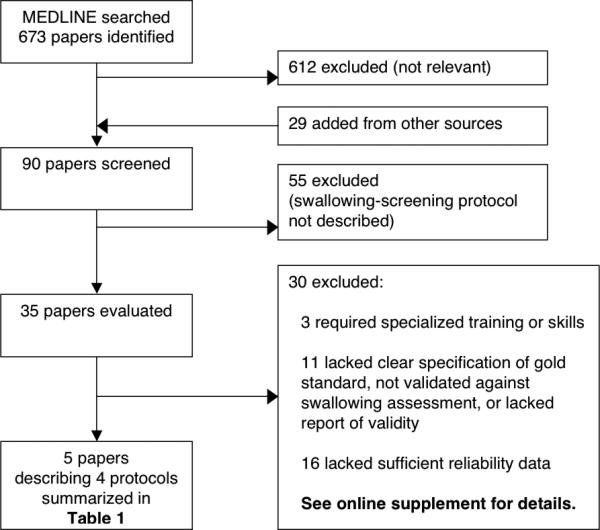

Results of the search are summarized in Figure 1 and yielded 35 papers describing protocols. Thirty papers were excluded because they failed to meet one or more of the required criteria as detailed in the online supplement.

Figure 1.

Selection of swallowing-screening protocols for review

Table 1 provides details on four protocols described in four papers and one abstract. Content of all four protocols included items previously shown to be important in identifying dysphagia and risk for aspiration.8 Two included assessment of mental status,2-4 whereas the other two protocols excluded subjects with diminished consciousness.5,6 All protocols included some assessment of oropharyngeal function such as dysarthria, dysphonia, and asymmetry or weakness of the face, tongue, and palate. All but one4 included assessment of ability to swallow water. The emergency physician screen5 included use of pulse oximetry in conjunction with water swallow. Extracts from the papers describing these protocols are included in the online supplement, except for the one that was proprietary.6

Table 1.

Comparison of swallowing-screening protocols meeting basic criteria

| Protocol (N) | Administration | Reliability* | Gold Standard and Validity† |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Stroke Dysphagia Screen2,3 (ASDS/SWALLOW-3D) (N=300 & 225) | By nurses 2 minutes to administer 10 minute training |

K=0.94 | Study 1: Dysphagia by MASA score<178, N=300 Sensitivity 91% (95% CI 82-95), Specificity 74% (95% CI 64-80), PPV 54%, NPV 95% Study 2: Dysphagia on video-fluoroscopy, N=225 Sensitivity 94% (95% CI 88-98), Specificity 66% (95% CI 57-75), PPV 71%, NPV 93% |

| Modified Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability4 (MMASA) (N=150) | By stroke neurologists minutes to administer training time unknown |

K=0.76 | Dysphagia by MASA score<178 Examiner 1: Sensitivity 93% (95% CI 82-98), Specificity 86% (95% CI 78-93), PPV 79%, NPV 95% Examiner 2: Sensitivity 87% (95% CI 75-95), Specificity 84% (95% CI 75-91), PPV 76%, NPV 92% |

| Emergency Physician Swallowing Screening5 (N=84) | By emergency physicians ≤3 minutes to administer training time unknown |

K=0.90 | Dysphagia on formal swallowing evaluation Sensitivity 96% (95% CI 85-99), Specificity 56% (95% CI 38-72%), PPV 74%, NPV 91% |

| Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test6 (TOR-BSST) (N=311) | By nurses 10 minutes to administer 4 hour training |

ICC=0.92 | Dysphagia on video-fluoroscopy (acute patients) Sensitivity 96% (95% CI 73-99), Specificity 64% (95% CI 35-85), PPV 77% (95% CI 53-90), NPV 93% (95% CI 58-99) |

Inter-rater reliability with K = kappa and ICC = intra-class correlation coefficient

MASA = Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability;7 CI = confidence interval; PPV = positive predictive value; and NPV = negative predictive value.

All protocols took place at tertiary care medical centers, although the TOR-BSST6 was validated in two acute care and two rehabilitation hospitals. The emergency physician screen5 and the MMASA4 were self-characterized as preliminary because of small sample sizes of 84 and 150 subjects, respectively. Furthermore, the MMASA4 was only validated with administration by two neurologists. Training was described as simple and screenings took only minutes. None of the studies examined outcomes of pneumonia, prolonged hospital stay, disability, or death, aside from the study detailing the emergency physician screen, which reported incidence of pneumonia to be 6% in their cohort.5

Discussion

In this systematic review, only four swallowing screening protocols met basic criteria for reliability, validity, and feasibility. Despite our efforts, we may have missed a relevant paper or inappropriately excluded one. This dearth of sound, published screening protocols may have adversely affected broad implementation of early screening for all acute stroke patients.

All four screening protocols identified were published within the last two years, perhaps motivated by the previous Joint Commission requirement, which was subsequently dropped.9 Two of the four were promising but preliminary with small sample sizes.4,5 Of those remaining, the ASDS/SWALLOW-3D2,3 has two advantages over the TOR-BSST.6 First, the TOR-BSST was validated using videofluoroscopic swallowing study in a small, random sub-sample (n=24) of those with acute stroke. The ASDS/SWALLOW-3D was validated using videofluoroscopy in 225 patients with acute stroke, although these data have been presented only as an abstract thus far.3 Also, the TOR-BSST is copyrighted, requiring purchase to be administered. Its purchase includes online training and information on how to implement the screening protocol, which may be desirable for some facilities.

Such studies face many challenges, perhaps explaining the small number of high-quality studies identified in this review. Ensuring that health-care providers are sufficiently trained to administer a screen reliably any time of day or night is problematic. Screening that is done at one time may be compared with a gold standard done at a later time when dysphagia may have improved. Finally, we have not addressed the reliability of formal evaluations or their validity with respect to pneumonia, prolonged hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality.

Several observational studies suggest that screening may help prevent aspiration pneumonia10-12 but cannot distinguish whether lower frequency of pneumonia is attributable to the use of a swallowing screen itself or to other characteristics of a medical center. Also, these studies used a variety of different formal and informal screening techniques. Placebo-controlled randomized trials in high-volume stroke centers may be difficult to conduct now that swallowing screening has become common practice. Alternatively, the effectiveness of different screening strategies could be evaluated.

Further research is particularly needed to evaluate cost effectiveness of swallowing screening in this population. Potential benefit may be seen not only in terms of pneumonia, but also in terms of length of hospital stay, morbidity, and mortality. But screening carries risks due to false positive results, which may lead to unnecessary withholding of oral feeding or placement of feeding tubes. The positive predictive values of protocols we reviewed ranged from 54 to 77%. Thus, 23 and 46% of patients screened were falsely identified as having increased risk.

Finally, effective screening depends not only on careful analysis of costs and benefits but also on availability of effective interventions for those identified as being at high risk. Once reliability, validity, and feasibility of swallowing screens and formal swallowing evaluations are established, effectiveness of interventions needs to be addressed. Only through such efforts will the use of swallowing screens in patients after acute stroke be established as evidence based.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

A grant from National Institute of Neurologic Disease and Stroke (5T32NS051171-04) supported Dr. Schepp.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Martino R, Foley N, Bhogal S, Diamant N, Speechley M, Teasell R. Dysphagia after stroke: incidence, diagnosis, and pulmonary complications. Stroke. 2005;36:2756–2763. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190056.76543.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edmiaston J, Connor LT, Loehr L, Nassief A. Validation of a dysphagia screening tool in acute stroke patients. Am J Crit Care. 2010;19:357–364. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edmiaston J, Connor LT, Ford AL. SWALLOW-3D, a simple 2-minute bedside screening test, detects dysphagia in acute stroke patients with high sensitivity when validated against video-fluoroscopy (abstract). Stroke. 2011;42:e352. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonios N, Carnaby-Mann G, Crary M, Miller L, Hubbard H, Hood K, et al. Analysis of a physician tool for evaluating dysphagia on an inpatient stroke unit: the Modified Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;19:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner-Lawrence DE, Peebles M, Price MF, Singh SJ, Asimos AW. A feasibility study of the sensitivity of emergency physician dysphagia screening in acute stroke patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martino R, Silver F, Teasell R, Bayley M, Nicholson G, Streiner DL, et al. The Toronto Bedside Swallowing Screening Test (TOR-BSST): development and validation of a dysphagia screening tool for patients with stroke. Stroke. 2009;40:555–561. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.510370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann G. The Mann Assessment of Swallowing Ability. Singular; Clifton Park, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenbek JC, McCullough GH, Wertz RT. Is the information about a test important? Applying the methods of evidence-based medicine to the clinical examination of swallowing. J Commun Disord. 2004;37:437–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reeves MJ, Parker C, Fonarow GC, Smith EE, Schwamm LH. Development of stroke performance measures: definitions, methods, and current measures. Stroke. 2010;41:1573–1578. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Odderson IR, Keaton JC, McKenna BS. Swallow management in patients on an acute stroke pathway: quality is cost effective. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1995;76:1130–1133. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(95)80121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinchey JA, Shephard T, Furie K, Smith D, Wang D, Tonn S. Formal dysphagia screening protocols prevent pneumonia. Stroke. 2005;36:1972–1976. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177529.86868.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lakshminarayan K, Tsai AW, Tong X, Vazquez G, Peacock JM, George MG, et al. Utility of dysphagia screening results in predicting poststroke pneumonia. Stroke. 2010;41:2849–2854. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.