Abstract

The HIV/AIDS epidemic continues to grow in pockets across Asia, despite early successes at curtailing its spread in countries like Thailand. Recent evidence documents dramatic increases in incidence among risk groups and, alarmingly, the general population. This meta-analysis summarizes the sexual risk-reduction interventions for the prevention of HIV-infection that have been evaluated in Asia. Sexual risk-reduction outcomes (condom use, number of sexual partners, incident sexually transmitted infections [STI], including HIV) from 46 behavioral intervention studies with a comparison condition and available by August 2010 were included. Overall, behavioral interventions in Asia consistently reduced sexual risk outcomes. Condom use improved when interventions sampled more women, included motivational content, or did not include STI testing and treatment. Incident HIV/STI efficacy improved most when interventions sampled more women, were conducted more recently, or when they included STI counseling and testing. Sexual frequency efficacy improved more in interventions that were conducted in countries with lower human development capacities, when younger individuals were sampled, or when condom-skills training was included. Behavioral interventions for reducing sexual risk in Asia are efficacious; yet, the magnitude of the effects co-varies with specific intervention and structural components. The impact of structural factors on HIV intervention efficacy must be considered when implementing and evaluating behavioral interventions. Implications and recommendations for HIV/AIDS interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Meta-analysis, East Asia, HIV/AIDS, intervention efficacy, sexual risk-reduction, review

Introduction

Asia is home to more than half of the world’s population and five million people living with HIV (UNAIDS, 2008). Given the population in Asia, even a small increase in the incidence of HIV could reshape the pandemic worldwide (WHO, 2001). During the early 1990s, the HIV epidemic gained a foothold in East Asian countries like Thailand and India, and HIV-infections have steadily spread (Lu et al., 2008; Park et al., 2010; Ruxrungtham et al., 2004). Drivers of the HIV/AIDS epidemic vary from region to region, with countries in East Asia carrying the burden of the disease. HIV typically commences among injection drug users and female sex workers; it spreads to male clients of sex workers and to the clients’ female sexual partners (Ruxrungtham et al., 2004). Sexual “bridging” between clients of sex workers and their steady partners constitutes a primary route through which HIV is spread from high- to low-risk groups (Gorbach et al., 2000; Hesketh et al., 2005). Recent epidemiological data indicate high rates of unprotected sex among men who have sex with multiple and concurrent male and female partners, and among men who have sex with men (Choi et al., 2003; Hernandez et al., 2006). HIV/AIDS prevalence in East Asia, coupled with a high burden of tuberculosis co-morbidity and increasing resistance to antiretroviral medication, necessitates the development and dissemination of effective HIV risk-reduction interventions (Lau et al., 2007; Narain & Lo, 2004).

Asia is as politically, culturally, and economically diverse regionally as its HIV/AIDS epidemic. East Asian nations have been especially influenced by globalization, with four of the world’s fastest growing economies in the 80s and 90s (i.e., Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) and India and China undergoing astonishing economic growth. Not only has such economic growth altered the course of labor migration patterns across Asia, it has fueled the development of several industrial sectors, one of the most prolific being the sex work industry (Lim & International Labour Office, 1998). Growth has left wide economic disparities between the rich and poor, with many Asian countries among the poorest worldwide. For example, 36% of China’s population earns less than $2 a day (OPHI, 2010). Each year, increasing numbers of women from dire economic circumstances enter sex trade, making female sex workers one of the largest migrant populations in Asia. Such rapid economic development has not been associated with comparable advancement in social and political developments. Therefore, while large-scale implementation of 100% condom use policies in Thailand and Cambodia have seen significant reductions in STI and HIV infections, women working in the sex trade industry continue to face gender-based discrimination and violations of their social, economic, and political rights.

Many prevention trials have been conducted in Asia. Yet, surprisingly little is known about best-practice intervention strategies for reducing sexual risk behavior in the context of unique historical and development patterns in Asia. It is conceivable that, given the lower status of women, particularly female sex workers, and their limited social, economic, and political rights, interventions that include more women in the sample and provide relevant resources should see greater intervention success. Similarly, interventions that incorporate socially and culturally relevant content in teaching safer sex skills should bode success in regions, especially where human development levels are low (Huedo-Medina et al., 2010). Because behavioral interventions have had varying efficacy in Asia, it is critical to review them to determine (a) when and where they have been most efficacious (Tan et al., 2010), (b) what study components, approaches, and delivery modes are most useful, (c) what population and sample characteristics are related to efficacy, (d) if structural-level factors such as women’s rights and the human development index (HDI, an index of development based on life expectancy, educational attainment, and income) explain variations in intervention success, and (e) how patterns may differ in the risk outcomes assessed. This paper reports the results of the first meta-analysis of behavioral interventions implemented to reduce HIV-risk in Asia. Moderator analyses were also conducted to identify and explain heterogeneity in study outcomes, focusing on study methods as well as structural features associated with the nations in which the trials were conducted.

Method

Sample of Studies and Selection Criteria

We searched for studies in English through the simultaneous use of three main strategies: (a) We searched electronic reference databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and AIDSearch) using terms related to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases: HIV OR AIDS OR (human AND immu* AND virus) OR (acquired AND immu* AND deficien* AND syndrome) OR STD OR STI OR (sexually AND transmitted AND disease*) OR (sexually AND transmitted AND infection*) OR chlamydia OR gonorrhea, etc.), prevention (i.e., prevent* OR interven*), and sexual behavior (i.e., sex* OR condom* OR intercourse). These terms were joined with the names of Asian nations. Inclusion of Asian nations was based on the UNAIDS definition of Asia, which excludes nations in Central Asia/Eastern Europe. (b) We searched HIV-related listservs, the NIH database of grant awardees, and conference proceedings (e.g., the International AIDS Conference). (c) We searched the reference lists of obtained studies and reviews.

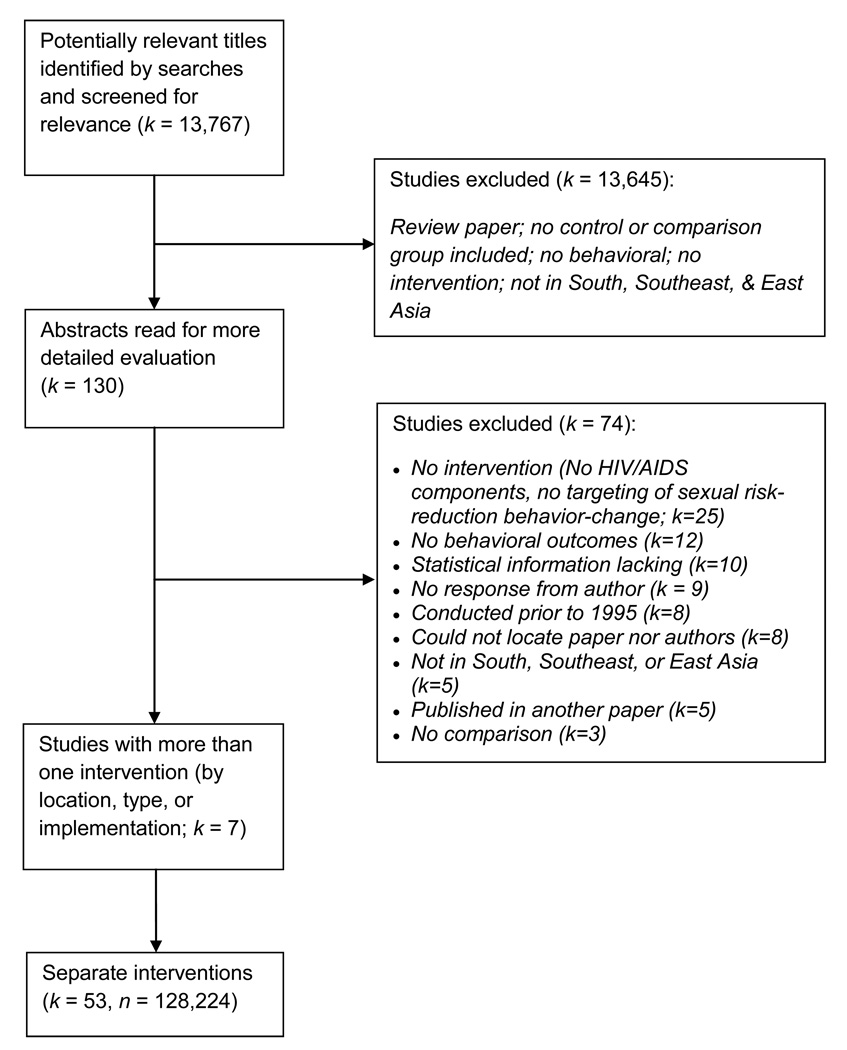

Studies available by August 2010 were eligible for inclusion if they (a) examined an HIV risk-reduction intervention in an Asian nation; (b) used a randomized controlled trial, a quasi-experimental design with a control group, or a pre-post intervention design; and (c) measured a behavioral and/or biological sexual risk-reduction marker following the intervention. Studies were excluded if they (a) included perinatal transmission contexts or behaviors; (b) did not use a behavioral intervention; (c) did not focus on HIV/AIDS, or (d) could not be located or authors could not be reached to complete missing study details. Consistent with meta-analytic convention (Cooper et al., 2009), when a study reported on the effectiveness of multiple interventions, each intervention was examined individually. Attempts were made to contact authors to procure information for analysis wherever lacking. Of 13 studies whose authors contacted, nine were excluded for lack of response. Matching selection criteria were 46 articles; six studies provided separate intervention statistics and were treated as individual interventions. Thus, 53 interventions from 46 articles qualified for the analysis, whose total sample size was 128,224 individuals (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection Process for Study Inclusion.

Gauging Intervention Features

Two trained raters independently coded studies for (a) geographical location; (b) sample characteristics (e.g., n at baseline and first follow-up, mean age, proportion female, HIV and other sexually transmitted infection prevalence); (c) intervention characteristics (e.g., length of sessions, delivery method); (d) intervention content (e.g., skills training, condom distribution, trans-situational motivational strategies that tap personal life goals and core social values (Carey & Lewis, 1999); and (e) design and measurement characteristics (e.g., presence of a control group, assignment to conditions). Inter-coder reliability was high for categorical dimensions (average Kappa = 0.92) as well as for continuous variables (average Spearman-Brown correlation = 0.98).

Structural features were derived from the United Nations Development Programme’s Human Development Reports (UNDP, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006), the World Bank’s World Development Indicators database (Bank, 2007), and the Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset (Cingranelli & Richards, 2008), matching indicators to the nation of each trial and the year when the trial commenced. Specifically, HDI values were obtained for each country from the Human Development Reports; these HDI values approximate a nation's level of development based on longevity, GDP per capita, and level of education. Income equality was indicated by the Gini index, such that greater income equality is related to higher levels of development in wealthy nations. Gini values were obtained from the World Development Indicators database, and are an approximation of economic inequality within a nation based on a scale ranging from 0 (lowest) to 0.99 (highest). Last, measures depicting the extent to which women’s political rights are protected by law were obtained from the CIRI Human Rights Dataset and coded based on the presence and active enforcement of laws ensuring the equality of women (0 = complete absence of protection to 2 = complete institution and enforcement of laws). This dataset coded women’s political rights as characterized by a woman’s right to participate in politics, such as having the right to vote, run for political office, and petition government officials. When a value for a year was missing, it was imputed by regression interpolating the function of the reported data in the earlier and more recent two years.

Gauging Efficacy and Assessing Effect Modifiers

We calculated individual effect sizes for nine outcomes: (a) condom use with an unspecified partner, (b) condom use with a steady partner, (c) condom use with a casual partner, (d) condom use with a client (for female sex workers), (e) sexual intercourse with female sex workers, (f) number of sexual occasions, (g) number of sexual partners, (h) incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and (i) HIV seroconversions. Summary indicators were generated for condom use (averaging the first four outcomes); sexual frequency (the next four outcomes); and biological outcomes (the last two outcomes).

For continuous outcomes, we calculated effect sizes in the form of the standardized mean difference, d, which is defined as the mean difference between the intervention and control group (or baseline) divided by the pooled standard deviation (or standard deviation of the pretest for paired comparisons) (Becker, 1988; Hedges & Olkin, 1985). Positive values implied risk-reduction (e.g., reduction in frequency of unprotected sex) and negative effect size risk elevation. When means and standard deviations were not available, other inferential statistics (e.g., t- or F-values) were used to calculate d (Johnson & Eagly, 2000; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Finally, for dichotomous variables, we calculated an odds ratio which we transformed to d using the Cox transformation (Sánchez-Meca et al., 2003). Effect sizes were corrected for sample size bias and, in the case of between-group designs, for baseline differences (Becker, 1988). Effect sizes were calculated for measures provided at the first follow-up (most interventions had only one such follow-up).

For all outcomes, analyses followed random- and fixed-effects assumptions to estimate means. Homogeneity of the effect sizes (I2) was also assessed (Higgins & Thompson, 2002; Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). Two strategies were used to evaluate asymmetries suggestive of publication bias: Begg’s strategy (Begg & Mazumdar, 1994) and Egger’s test (Egger et al., 1997). To test for possible dependence, sensitivity analyses were conducted where the same control group was used as the comparison group for multiple comparisons. We tested whether coded features modified the observed effects for each of the three composite outcomes. Statistically significant outliers (i.e., values that were more than three standard deviations from the average effect size) were winsorized to the values at 90th percentile to have more robust estimations reducing the influence of the outliers (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Study dimensions that related to the variability of each of the three outcomes were entered into a series of models that controlled for intercorrelations among the dimensions. These models determined the extent to which variation may be uniquely attributed to study dimensions adjusting for the effect of the other variables. Only study dimensions that retained statistical significance (Bonferroni p ≤ 0.001) and exhibited stable coefficients across the series of models were retained. To determine the robustness of models, we re-evaluated the surviving study dimensions using mixed-effects model (i.e., random-effects constant following maximum-likelihood assumptions, fixed-effects slopes), which is known to be more statistically conservative because it explains a portion of the variation in effect size through the unconditional variance (Hedges & Vevea, 1998).

Results

Description of Studies

Table 1 describes the interventions, samples, and the programmatic features. Of the 53 interventions from 46 studies conducted in Asia with 128,224 individuals, 16 were implemented in China, 11 in Thailand, 10 in India, 5 in Indonesia, 4 in the Philippines, 3 in Hong Kong, 2 in Singapore, and 1 each in Cambodia and Nepal. The mean HDI of these countries during the year of data collection was 0.71 (SD = 0.13; range: 0.35 to 0.94) (for comparison, the HDI for the U.S. in 2009 was 0.95). The majority of interventions (44 [83%]) took place in urban settings. Twenty-seven interventions (51%) included only women, 15 (29%) included only men, and the remainder included both genders (11 [20%]). The mean age of participants was 26.5 years (SD = 5.47). Thirty-five interventions (66%) used between-group comparisons whereas 18 (34%) used within-group comparisons. The initial follow-up assessment occurred at a mean of 235 days (range: 0 – 730 days) post-intervention, with four interventions that took measures immediately after intervention. Most (k = 34, 64%) devoted at least three hours to intervention delivery and the rest were shorter.

Table 1.

Descriptive features of 54 interventions from 46 studies in the sample.

| Authors | Year Published |

Study Design1 |

Intervention Type2 | Sample | Intervention Features3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdullah et al. | 2003 | Quasi | School-based | 840 children from four intermediate schools in Hong Kong | Classroom-based sex & HIV/AIDS education program promoting condom use |

| Basu et al. | 2004 | Community RCT | Empowerment, Structural | 200 FSW in Cooch Behar, Dinhata, India | SONAGACHI Project: community-level, peer-led skills training, HIV/AIDS education, community-wide awareness & local stakeholder involvement, condom promotion, STI treatment |

| Bentley et al. | 1998 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | 1,628 seronegative men attending STI clinics in Pune, India | HIV, STI testing, counseling, & treatment; HIV/AIDS education, condom promotion & distribution |

| Bhatia et al. | 2005 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | Men aged 18–45 in impoverished community, Chandigarh, India | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; skills training |

| Bhave et al. | 1995 | Quasi | Behavioral change for FSW | Establishment-based FSW & madams in Mumbai (Bombay), India | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; STI treatment; education for brothel managers (madams) |

| Busza & Baker | 2004 | Pre-Post | Empowerment, Structural | Young, establishment-based migrant Vietnamese FSW in Phnom Penh, Cambodia | Introduction of female condoms; activity-based skills training; STI treatment; condom promotion; community-wide awareness & local government agencies involvement |

| Celentano et al. | 2000 | Quasi | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | Male conscripts in Royal Thai Army in northern provinces, Thailand | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; testing & counseling; STI treatment; activity-based skills training |

| Chen & Liao | 2005 | Pre-Post | IDU risk-reduction | Female IDUs aged 19–48, Guangxi Province, China | Harm reduction (no needle exchange) using culture-based relational model (including family members or friends); HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion |

| Cornman et al. | 2007 | Group RCT | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | Long-distance truck drivers in Tamil Nadu, India | Information-Motivation-Behavioral (IMB) model intervention |

| Feng et al. | 2009 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with MSM | 1,772 young MSM aged 20–29 in Chongqing, southwest China | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; counseling & testing |

| Fontanet et al. | 1998 | Group RCT | Empowerment | FSW from 71 establishments in four cities in Thailand | Introduction of and skills training on female condoms use |

| Ford & Koetsawang | 1999 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | 475 high- & low-income FSW in Nakhon Pathom, central Thailand | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion; STI treatment; skills training; involvement of sex establishment staff to institute condom use policy |

| Ford, Wirawan, Fajans et al. | 1996 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | 1,586 establishment-based FSW in Denpasar, Bali, Indonesia | INTERVENTION 1 (CARIK): Condom promotion & distribution to sex workers; STI treatment; skills training |

| Quasi | INTERVENTION 2 (SANUR): Condom promotion & sales to clients; STI treatment; skills training | ||||

| Ford, Wirawan, Reed et al. | 2002 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with FSW | Low-income, establishment-based FSW, brothel managers, and clients in Bali, Indonesia | LOW IMPACT (one session every 6 months): HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; skills training; counseling & testing; client & brother manager education |

| Pre-Post | HIGH IMPACT (three sessions every 6 months): HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution; skills training; counseling & testing; client & brothel manager education | ||||

| Ford, Wirawan, Suastina et al. | 2000 | Quasi | Peer-education | FSW aged 15–42 in Bali, Indonesia | Peer-led HIV/AIDS education & skills training; condom promotion; STI treatment; counseling & testing |

| Gangopadhyay et al. | 2005 | Quasi | Empowerment, Structural | Establishment-based FSW in Sonagachi red light district, Calcutta (Kolkata), India | Peer-led HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion & distribution |

| Gilada | 1999 | Pre-Post | Empowerment, Structural | 5,500 FSW in Bombay, 3,500 in Pune, India | Project SAHELI: Peer-led HIV/AIDS education & skills training; sex work legitimacy (photo-identity cards provided to sex workers; newsletter); STI treatment; condom promotion & distribution |

| Jana & Singh | 1995 | Pre-Post | Empowerment, Structural | Establishment-based FSW in Sonagachi red light district, Calcutta, India | SONAGACHI Project: Peer-led education & skills training; legitimacy of sex work; community-wide awareness & local stakeholder involvement; microloans |

| Kawichai et al. | 2004 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with heterosexual adults | 2,251 young adults aged 19–35 living in Chiang Mai, northern Thailand | HIV counseling & testing; condom use education |

| Kumar et al. | 1998 | Quasi | IDU risk-reduction | Street-recruited male IDUs in Madras (Chennai), India | Community-based outreach; HIV/AIDS education; bleach & condom distribution; health care referral |

| Latkin et al. | 2009 | RCT | IDU risk-reduction | 427 male IDUs and risk partners in Chiang Mai, Thailand | Peer-led HIV/AIDS education & skills training based on network model (recruiting social network index as peer educators); HIV counseling & testing |

| Lau, Lau, Cheung et al. | 2008 | RCT | Behavioral change with MSM | Young, internet-recruited MSM in Hong Kong | E-mail-based intervention using individualized feedback for risk-reduction |

| Lau, Tsui, Cheng et al. | 2010 | RCT | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | 301 male cross-border truck drivers in Hong Kong | Counseling & testing; HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion |

| Li, Stanton, Wang et al. | 2008 | Group RCT | School-based | 380 college students from four universities in Nanjing, China | Culturally-adapted HIV/AIDS education and condom use promotion |

| Li, Wang, Fang et al | 2006 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | Young female sex workers in southern China | Culturally-adapted intervention: Counseling & testing, condom promotion, HIV/AIDS education |

| Ma et al. | 2002 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with FSW | 966 FSW in Guangzhou, China | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion; skills training; STI testing & treatment |

| Morisky, Ang, Coly et al. | 2004 | Quasi | Peer-education; structural | 3,389 male clients of FSW in southern Philippines | Peer-led HIV/AIDS education, condom promotion, skills training; community-wide awareness & local stakeholder involvement |

| Morisky, Chiao, Stein et al. | 2005 | Quasi | Peer-education; structural | 369 FSW in four cities south of Manilla, Philippines | WORKERS only: Peer-led HIV/AIDS education, condom promotion, skills training |

| Quasi | MANAGERS only: HIV/AIDS education, manager-led condom promotion | ||||

| Quasi | COMBINED (managers & workers) | ||||

| Morisky, Nguyen, Ang et al. | 2005 | Quasi | Peer-education | Young male taxi & tricycle drivers in southern Philippines | Condom use promotion; skills training; peer-led HIV/AIDS education |

| Morisky, Stein, Chiao et al | 2006 | Community RCT | Peer-education | 897 FSW in four cities south of Manilla, Philippines | PEER + MANAGER: Multilevel intervention using manager- & peer-led condom promotion |

| Community RCT | PEER only: Peer-led condom promotion | ||||

| Muller et al. | 1995 | Quasi | Behavioral change with heterosexual adults | Young, seropositive adults in Bangkok, Thailand | Counseling & testing |

| Peak et al. | 1995 | Pre-Post | IDU risk-reduction | 507 IDUs in Kathmandu, Nepal | Clean needles exchange; STI treatment; condom promotion & distribution |

| Sherman et al. | 2009 | RCT | Peer-education | 1,189 young methamphetamine users ages 18–25 in Chiang Mai, Thailand | Peer network intervention using peer-led HIV/AIDS education, skills training, condom promotion |

| Tripiboon | 2001 | Community RCT | Community-wide intervention | 607 married women aged 18–49 in rural northern Thailand | Community-wide awareness & local stakeholder involvement; HIV/AIDS education; skills training |

| Ubaidullah | 2004 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | 300 male truck drivers aged 25–45 in Andhra Pradesh, India | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion |

| van Griensven et al. | 1998 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | Establishment-based FSW in Sungai Kolok, Betong, Thailand | Voluntary counseling & testing; HIV/AIDS education; peer-led condom promotion & distribution |

| Visrutaratna et al. | 1995 | Pre-Post | Community-wide intervention | FSW from 43 establishments in Chiang Mai, Thailand | “Superstar” & “Model brothel” programs: Peer-led HIV/AIDS education; peer- and manager-led condom promotion |

| Wang & Keats | 2005 | Quasi | Behavioral change with heterosexual men | 450 men aged 17–39 from three ethnic groups in Sichuan province, China | DIRECT: HIV/AIDS education; involvement of peer educators to develop risk-reduction intervention materials |

| Quasi | INDIRECT: Peer-led HIV/AIDS education, skills training, and condom promotion | ||||

| Wong, Chan, & Koh | 2004 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | 1,259 young establishment-based migrant (Malaysian Chinese) FSW in Singapore | Condom use promotion; mandatory STI testing; skills training; HIV/AIDS education |

| Wong, Chan, Lee et al | 1996 | Quasi | Behavioral change with FSW | 253 establishment-based FSW from two locales in Singapore | HIV/AIDS education; condom promotion; skills training |

| Wu et al. | 2007 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with FSW | Establishment-based FSW from three towns in Yunnan province, China | HIV/AIDS education & condom promotion with workers and managers/establishment owners; discounted condoms |

| Xiaoming, et al. | 2000 | Community RCT | Community-wide intervention | Young adults aged 18–30 in Kunshan county, China | HIV/AIDS education integrated into existing family planning program; condom promotion & distribution |

| Xu, Kilmarx, Supawitkul et al. | 2002 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with heterosexual adults | 648 STI-clinic patients in Shanghai, China | Clinic-based counseling & testing; skills training; condom promotion |

| Xu, Wang, Zhao et al. | 2002 | RCT | Behavioral change with heterosexual adults | 779 young, married, seronegative women in Chiang Rai, Thailand | Video-based HIV/AIDS education |

| RCT | Video-based HIV/AIDS education + risk-reduction discussion with medical doctor during clinic visit | ||||

| Ye et al. | 2009 | Quasi | School-based | 893 high school students in Hong Kong | Peer-educators training; teacher-led HIV/AIDS education |

| Zhu et al. | 2008 | Pre-Post | Behavioral change with MSM | 218 young MSM in three cities in Anhui province, China | Peer-led HIV/AIDS education |

Note. Abbreviations: MSM, men who have sex with men; FSW, female sex workers; IDUs, injection-drug users; STIs, sexually transmitted infections.

Pre-Post, within-subjects design with no comparison, Quasi, quasi-experimental design, RCT, randomized controlled trial with individuals as units of randomization, Group RCT, randomized controlled trial with groups as units of randomization, Community RCT, randomized controlled trial with communities as units of randomization.

Empowerment, Intervention strategies aimed to increase behavioral efficacy and in effecting intended and actual change, Structural, Intervention strategies focused on changing brothel- or community-based policies and garner community support and awareness.

Information-Motivation-Behavioral model guide intervention design to target increasing knowledge, motivation, and behavioral skills to change behavior.

Efficacy of the Interventions

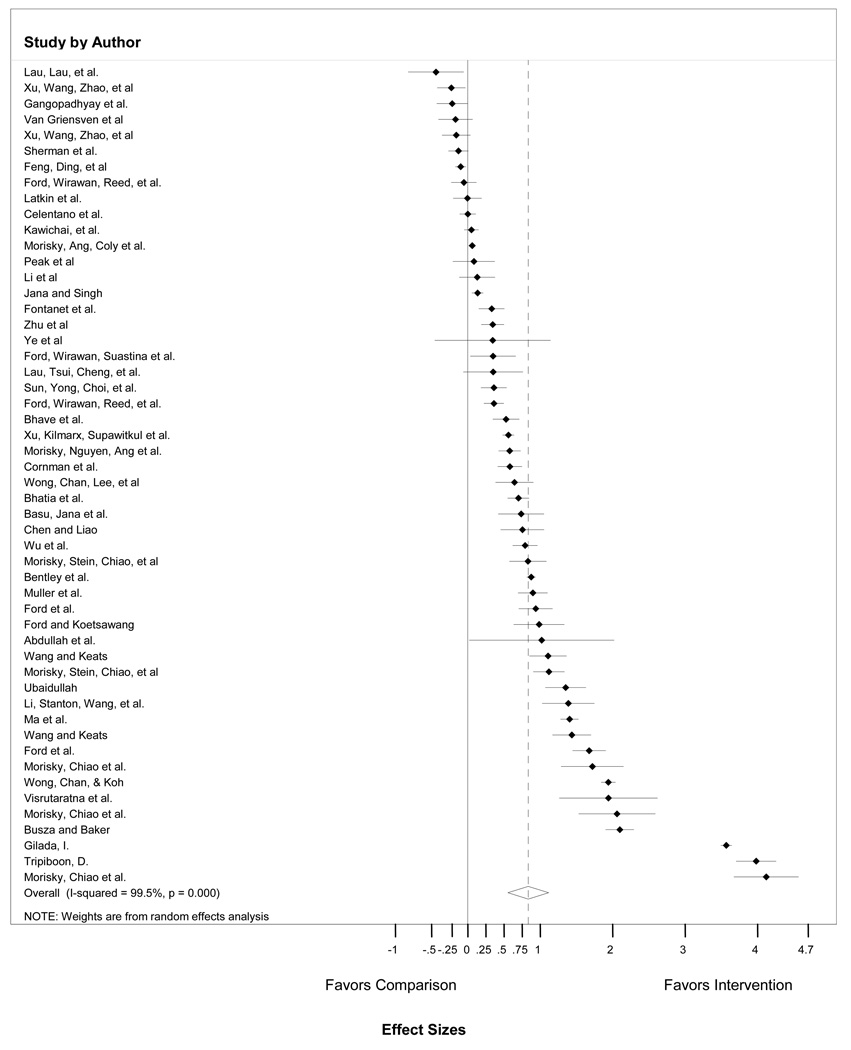

Condom use was assessed in 52 interventions (98%), HIV and/or STI incidence in 20 interventions (38%), and sexual frequency or partner type in 16 interventions (30%); 2 interventions (4%) assessed all three risk-reduction outcomes. As Table 2 shows, overall, interventions increased condom use, decreased sexual frequencies, and reduced the incidence of STIs, including HIV. There were no asymmetries suggestive of publication bias in condom use effect sizes, and some asymmetries suggestive of bias with overall sexual frequency and incident HIV/STIs effect sizes. Study findings lacked homogeneity, implying that a model based on the mean value is inadequate. Figure 1 portrays the distribution of condom use outcomes.

Table 2.

Weighted mean effect sizes of HIV-risk-reduction outcomes.

| Weighted mean d+ (95% CI) | Homogeneity of effect sizes |

Deviation from normality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | k | Fixed Effects | Random Effects | I2 (95% CI)a | Begg’s z | Egger’s t |

| Overall condom use | 52 | 0.57 (0.55, 0.59) | 0.73 (0.54, 0.93) | 98.99 (98.88, 99.09) | 2.68 (p=0.56) | 0.58 (p=0.13) |

| With steady sex partner | 7 | 0.25 (0.20, 0.31) | 0.48 (0.13, 0.83) | 96 (94.26, 97.62) | ||

| With casual sex partner | 14 | 0.70 (0.66, 0.74) | 0.41 (0.09, 0.73) | 98 (97.13, 98.28) | ||

| Overall sexual frequency | 16 | 0.05 (0.01, 0.09) | 0.17 (−0.037, 0.38) | 95 (93.25, 96.35) | 0.63 (p=0.01) | 1.61 (p=0.57) |

| Number of sex partners | 11 | 0.12(0.05, 0.18) | 0.18 (−0.11, 0.48) | 96 (93.72, 96.94) | ||

| STI and HIV incidence | 20 | 0.28 (0.25, 0.30) | 0.35 (0.10, 0.60) | 99.18 (99.05, 99.30) | 0.22 (p=0.23) | 0.85 (p=0.85) |

| HIV incidence | 6 | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94) | 1.19 (−0.11, 2.48) | 99.86 (99.84, 99.88) | ||

| Other STI incidence | 15 | 0.26 (0.22, 0.29) | 0.37 (0.07, 0.67) | 99.14 (98.97, 99.28) | ||

Note. Weighted mean effect sizes (d+) are larger than 0 for differences that favour the intervention group (lower HIV incidence) relative to the comparison (a control group or a pretest baseline assessment).

Values significantly higher than 0 imply the rejection of the hypothesis of homogeneity (i.e., there is more variability in effect sizes than expected by sampling error alone).

Effect Modifiers of Condom Use Efficacy

Four factors explained unique variation in condom use effect sizes: (a) STI/HIV counseling and testing, (b) use of motivational strategies, (3) proportion of women in the sample, and (d) methodological quality (Table 3). In the combined model, interventions were more successful at increasing condom use when they included higher proportions of women in the sample (β = 0.33), used motivational strategies (β = 0.27), had lower methodological quality (β = −0.23), and/or did not include STI/HIV counseling and testing (β = −0.41). Inspecting the estimates in Table 3, interventions evaluated with less rigorous methods appeared to be more efficacious with respect to condom use. Among the factors that related to condom use efficacy on a bivariate basis (Appendix 1 INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE) but that ceased being significant in the mixed model were HDI, interpersonal skills training, and HIV testing and counseling.

Table 3.

Moderators of Condom Use Effect Sizes (k = 52)a.

| All comparisons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study dimension and levelb | Adjustedc d+ (95% CI) | β value | |

| Percentage of women in sample | 0.33** | ||

| 0% | 0.43 (0.05, 0.82) | ||

| 100% | 0.97 (0.71, 1.24) | ||

| Methodological quality | −0.23* | ||

| Low quality | 1.08 (0.63, 1.54) | ||

| High quality | 0.25 (−0.40, 0.90) | ||

| Trans-situational motivational strategies | 0.27* | ||

| Absent | 0.55 (0.32, 0.78) | ||

| Present | 0.98 (0.61, 1.36) | ||

| Provided testing and treatment for STIs | −0.41* | ||

| Absent | 0.96 (0.70, 1.22) | ||

| Present | 0.63 (0.30, 0.96) | ||

Note. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; d+, weighted mean effect size; STI, sexually transmitted infection; significance of the standardized regression coefficient is denote as

p<.05;

p<.01

p<.001.

Condom use effect sizes for 52 studies were modeled as the dependent variable in weighted least-squares multiple regression, with four study dimensions simultaneously entered as independent variables and the inverse variance as the weights following mixed-effects assumptions. Positive effect sizes imply better condom use efficacy for the intervention group relative to the comparison group adjusted for the other variables in the model. High and low values for moderator category reflect maximum and minimum values in sample. The model explains 40% of the variance in effect sizes.

High and low values for moderator category reflect maximum and minimum values in sample.

The trans-situational motivational strategies and provide STI testing and treatment were contrast coded and the other two variables were zero-centered. High quality is reflective of high methodological quality score.

Effect Modifiers of Sexual Frequency Efficacy

Three factors explained the variation in effect sizes for sexual frequencies: (a) HDI, (b) age, and (c) condom skills training (Table 4). Reductions in sexual frequency were greater for older samples (β = 0.24), for interventions that included condom skills training (β = 0.41), and/or are conducted in countries with low HDI (β = −0.43). Other factors (e.g., percentage of women in sample, risk-awareness or feedback, and study quality) were related to efficacy on a bivariate basis (Appendix 2 INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE) but ceased being significant in the combined model.

Table 4.

Moderators of Sexual Frequency Effect Sizes (k = 16).

| All comparisons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study dimension and levela | Adjustedb d+ (95% CI) | β | |

| Human Development Index | −0.34*** | ||

| Low 0.35 | 0.45 (0.27, 0.62) | ||

| Medium 0.71 | 0.02 (−0.03, 0.07) | ||

| High 0.94 | −0.25 (−0.34, −0.16) | ||

| Mean age | −0.28*** | ||

| 15 years | 0.25 (−0.16, 0.34) | ||

| 42 years | −0.22 (−0.37, −0.06) | ||

| Condom skills training | 0.34*** | ||

| Absent | −0.10 (−0.16, −0.04) | ||

| Present | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21) | ||

Note. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; d+, weighted mean effect size; significance of the standardized regression coefficient is denote as

p<.05;

p<.01

p<.001.

The model was a weighted least-squares multiple regression, with study dimensions simultaneously entered as independent variables and the inverse variance as the weights, following fixed-effects assumptions. Positive effect sizes imply less sexual frequency efficacy for the intervention group relative to the comparison group adjusted for the other variables in the model. The model explains 38% of the variance, I2(3,12)=94.16 (95% CI=91.50, 95.99).

High and low values for moderator category reflect maximum and minimum values in sample.

Holding continuous factors constant at their mean, or, in the case of condom skills training, holding this factor constant through use of contrast coding.

Effect Modifiers of Incident HIV/STI Efficacy

Three factors explained the variation in effect sizes for HIV/STI incidence: As Table 5 shows, interventions were most efficacious when (a) they included STI counseling and testing (β = 0.41) as an intervention component, (b) collected data more recently (β = 0.60) and (c) sampled more women (β = 0.30). Three other factors were related to HIV/STI prevalence reduction on a bivariate basis (Appendix 3 INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE) but ceased being significant in the combined model, protection of women’s political rights, Gini index, and methodological quality.

Table 5.

Moderators of the Effect Sizes for Incident HIV and STI (k = 20).

| All comparisons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study dimension and levela | Adjustedb d+(95% CI) | β | |

| Percentage of women in sample | 0.30*** | ||

| 0% | 0.10 (0.06, 0.14) | ||

| 100% | 0.50 (0.46, 0.54) | ||

| Data collection year | 0.60*** | ||

| 1991 | −0.90 (−1.01, −0.80) | ||

| 2008 | 1.58 (1.48, 1.68) | ||

| Provided testing and treatment for STIs | 0.41*** | ||

| Absent | 0.38 (0.33, 0.43) | ||

| Present | 0.42 (0.39, 0.45) | ||

Note. Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; d+, weighted mean effect size; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; significance of the standardized regression coefficient is denote as

p<.05;

p<.01

p<.001.

The model was a weighted least-squares multiple regression, with study dimensions simultaneously entered as independent variables and the inverse variance as the weights, following fixed-effects assumptions. Positive effect sizes imply less incident HIV/STI efficacy for the intervention group relative to the comparison group adjusted for the other variables in the model. The model explains 33% of the variance, I2(3,16)=98.68 (95% CI=98.39, 98.92).

High and low values for moderator category reflect maximum and minimum values in sample.

Holding continuous factors constant at their mean, or, in the case of provided STI testing and treatment holding this factor constant through use of contrast coding.

Interactive Effects of HDI and Intervention Components

Because intervention efficacy may differ depending on the development level of the country, we conducted further analyses to explore the interactions between economic development and intervention components. We examined the interactive effects of HDI with intervention components at both the multivariate and bivariate levels. As Appendix 4 (INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE) shows, with regard to condom use efficacy, we found significant interactions between HDI and (a) inclusion of trans-situational motivation strategies (β = 0.44, p < .001), and (b) inclusion of relevant socially and culturally relevant content (β = −0.37, p < .001). Due to the small number of studies and lack of statistical power, these analyses were not conducted for the HIV/STI and sexual frequency outcomes.

Moderator Model Specification and Stability of Outcomes

Because studies with higher proportions of women in the sample were related to greater condom use, we explored whether this pattern was due to interventions focusing on female sex workers. When we included this variable in the model (100% female sex workers sample vs. not), proportion of women remained a significant predictor, which suggests that this effect is not an artifact of the female sex workers group per se. All the models were also tested under mixed-effects assumptions and the patterns were robust.

Discussion

The current meta-analysis provides the first comprehensive quantitative synthesis of behavioral interventions for HIV prevention across East Asia. Overall, the meta-analysis clearly supports the conclusion that behavioral risk-reduction interventions have been successful (Bingenheimer & Geronimus, 2009), consistent with past work on the efficacy of behavioral interventions for increasing condom use (Albarracín et al., 2005; Crepaz et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2011). These behavioral interventions have improved condom use, decreased the frequency of sexual-risk behavior, and reduced incidence of HIV and other STIs. Importantly, the efficacy of behavioral interventions varied widely not only across studies but also measured outcomes (Table 2). For example, provision of STI testing and treatment was efficacious at reducing incident infections but not at improving condom use. Indeed, provision of STI testing and treatment was associated with worse condom use efficacy, suggesting that testing and treatment alone may be effective at reducing incidence, but not via changes in condom use. Alternatively, while STI testing and treatment has been shown to be effective at reducing STI incidence (Grosskurth et al., 1995), other research shows effectiveness only in conjunction with risk-reduction counseling (Kamb et al., 1998).

Our synthesis supports a link between structural factors and individual behavioral risk for HIV, consistent with research in this area (Coates et al., 2008; DiClemente et al., 2007; Gupta et al., 2008; Holtgrave & Crosby, 2003; Latkin & Knowlton, 2005; Sumartojo, 2000). Results suggest that the interplay of sociostructural factors may indirectly impact intervention success across regions with varying resources, policies and laws, and levels of economic and social equality in at least four ways.

The efficacy of interventions that teach and develop individual skills was greatest in countries with the lowest human development levels, a pattern that is consistent with a prior meta-analysis focusing on Latin American and Caribbean nations (Huedo-Medina et al., 2010). The burden of disease (morbidity and mortality resulting from HIV/AIDS) translates to immeasurable loss in human productivity and capital (Piot et al., 2007). That even relatively small doses of risk-reduction programming can succeed is encouraging given resource deficits across regions in Asia.

Results emphasize the importance of understanding the particular socio-ecological structures of the target site in order to determine the “key ingredients” of intervention success. At the local level, communal activities are most common in Asia, and community-wide interventions incorporating peer-to-peer delivery and utilizing existing social structures were most efficacious. Additionally, HDI factored into the efficacy of particular intervention emphases and components. As Appendix 4 (INSERT LINK TO ONLINE FILE) illustrates, socio-culturally relevant interventions and/or those that included motivational components were most efficacious in low-development countries. That is, in countries with lower development levels (e.g., HDI below 0.75), theory-based motivational components that tap life goals and values were more efficacious at improving condom use. This improvement in efficacy, however, declined as human development levels increase, and interventions that did not include motivational components showed almost no differences in condom use efficacy by HDI of the country of the intervention. Similarly, socio-culturally relevant messages improved condom use much more in low-development countries.

Highly controlled interventions were least efficacious at improving condom use, whereas the low-quality studies were most efficacious. An aspect of high-quality trials is their use of active controls, which have been shown to contribute to smaller between-group effects because both the treatment and control groups may exhibit risk-reduction (de Bruin et al., 2009). Indeed, even high-quality interventions delivered later may be less efficacious than low-quality interventions delivered earlier due to prior intervention efforts for populations in a given location. Finally, the methodological scoring scheme used in the current analysis was derived for randomized control trial behavioral interventions, which may well be inappropriate for evaluating important aspects of structural interventions in developing nations (see Limitations for further discussion).

Intervention efficacy varied depending on the gender composition of the sample. Interventions were most successful at increasing condom use and reducing sexual risk to the extent that more women (or fewer men) were included in the study sample. Several explanations are plausible. First, this finding may be partially due to women assuming a social role as gatekeepers of the health and well-being of their families and communities. Second, interventions with more women in the samples may be attuned to the particular issues they face (e.g., in negotiating condom use with sexual partners) given structural-level forces such as gender inequality that contribute to women’s vulnerability to HIV/AIDS. By focusing on particular issues that women face, interventions have a better chance at increasing women’s efficacy for behavioral change. Third, the largest target group in our meta-analysis was female sex workers. In many parts of Asia, many interventions have targeted sex work establishments, and repeated exposure to risk-reduction messages from sources aside from the intervention is common (Poudel, 2011). Further, many female sex worker samples were in locales where 100% condom use policy was implemented (e.g., Thailand, Cambodia, parts of China). Intervention efficacy may be improved given sex workers’ exposure to institutionalized risk-reduction strategies and messages. Finally, health promotion trials generally succeed better among women relative to men (Johnson et al., 2010).

Implications for Future Intervention Research

The current meta-analysis of behavioral interventions clearly demonstrated that behavioral interventions are efficacious in reducing HIV-risk behavior and incident STI/HIV in Asia. Taken together, behavioral interventions were most efficacious at improving condom use when they targeted more women, incorporated trans-situational motivational strategies that tap personal life goals and core social values (Carey & Lewis, 1999), and/or excluded STI testing and treatment without risk-reduction counseling. The Sonagachi Projects (Basu et al., 2004) and Project Saheli (Gilada, 2000) are examples of such interventions. Behavioral intervention efficacy, at least in terms of condom use improvement, did not appear to be related to particular methods commonly used to evaluate clinical trials. However, whether methodological quality is related to intervention efficacy in Asia should be a focus of future research.

Limitations

As with any meta-analysis, we were limited by the studies available in three ways. First, there is a relative dearth of interventions for major risk populations. We were able to include only three interventions for men who have sex with men and five interventions for injection drug users, limiting our ability to investigate differences in intervention efficacy between different risk groups. Second, from the included studies, we were limited to the populations they targeted and the risk-reduction outcomes measured. For example, condom use outcome was the most widely assessed risk-reduction marker, with sexual frequency and incident HIV/STI measured in far fewer studies, limiting our ability to compare efficacy of particular study features across all three moderator models. Further, studies that measured sexual frequency outcomes tended to target majority-male, heterosexual samples. Therefore, the finding that interventions were more efficacious at reducing sexual frequency among younger than older samples, or when condom skills training was provided, may be apropos for men. Meta-analytic undertakings such as this one depend on the availability of studies, and implications from these results must be considered with this caveat in mind.

Structural-level indices such as HDI and the Gini index are imperfect indicators (Sagar & Najam, 1998). For example, if such indicators were available within the nations included, the observed relations would logically have been more marked. Nevertheless, they provided information for modeling the effects of structural factors on HIV outcomes. Third, we included structural-level interventions, which are difficult to evaluate. It was also the case that lower study-quality scores tended to be associated with structurally based interventions (e.g., peer- or community-based). Development of new and better methods will be necessary if we are to better evaluate structural-level interventions (Swendeman et al., 2009). Last, although we considered whether socially and culturally relevant dimensions were included in interventions, we did not include other potentially important cultural factors such as religion, which includes Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. Confucianism is both a religion and a pervasive relational norm (Lee & Tan, 2011). Future meta-analyses should consider the role of religion in various parts of the world where people follow a variety of different religious and cultural traditions.

Conclusion

In East Asia, particularly in countries with fewer resources, curtailing the HIV epidemic will require efficacious prevention programs. It is essential that such programs benefit from the knowledge generated by amassing extant evidence. Meta-analyses such as this one can help to accrue knowledge so that prevention resources can be deployed more effectively to avert a wider epidemic in East Asia.

Highlights.

the first, rigorous quantitative synthesis of HIV/AIDS intervention efficacy in Asian nations

HIV is spreading rapidly in pockets across Asia; such A state of affairs calls for swift evidence-based measures

Results are based on 53 HIV interventions examining dimensions of the interventions and of the nations in which they were conducted

Results have the potential to advance HIV prevention scholarship and inform changes at the policy level

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Forest Plot of Condom Use Effect Sizes Ordered from Smallest to Largest in Magnitude.

Acknowledgment

Preparation of this paper was supported by a National Institute of Mental Health traineeship (T32-MH074387) to Judy Y. Tan.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Judy Y. Tan, University of Connecticut.

Tania B. Huedo-Medina, University of Connecticut.

Michelle R. Warren, University of Connecticut.

Michael P. Carey, Brown University.

Blair T. Johnson, University of Connecticut.

References

- Albarracín D, Gillette JC, Earl AN, Glasman LR, Durantini MR, Ho M-H. A Test of Major Assumptions About Behavior Change: A Comprehensive Look at the Effects of Passive and Active HIV-Prevention Interventions Since the Beginning of the Epidemic. Psychological bulletin. 2005;131(6):856–897. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank World. World Development Indicators 2007. Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Lee SJ, Newman P, et al. HIV prevention among sex workers in India. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36(3):845. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker BJ. Synthesizing standardized mean-change measures. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology. 1988;41(2):257–278. [Google Scholar]

- Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50(4):1088–1101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingenheimer JB, Geronimus AT. Behavioral mechanisms in HIV epidemiology and prevention: past, present, and future roles. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;40(3):187–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2009.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey MP, Lewis BP. Motivational strategies can enhance HIV risk reduction programs. AIDS and Behavior. 1999;3(4):269–276. doi: 10.1023/a:1025429216459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Liu H, Guo Y, Han L, Mandel JS, Rutherford GW. Emerging HIV-1 epidemic in China in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2003;361(9375):2125–2126. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13690-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingranelli DL, Richards DL. The Cingranelli-Richards (CIRI) Human Rights Dataset Version 2008.03.12. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Coates TJ, Richter L, Caceres C. Behavioural strategies to reduce HIV transmission: how to make them work better. Lancet. 2008;372(9639):669–684. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60886-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York: Russel Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20(2):143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruin M, Viechtbauer W, Hospers HJ, Schaalma HP, Kok G. Standard care quality determines treatment outcomes in control groups of HAART-adherence intervention studies: implications for the interpretation and comparison of intervention effects. Health Psychology. 2009;28(6):668–674. doi: 10.1037/a0015989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiClemente RJ, Salazar LF, Crosby RA. A review of STD/HIV preventive interventions for adolescents: sustaining effects using an ecological approach. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(8):888–906. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilada IS. 'Project Saheli' for sex workers - A replicable model. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Gorbach PM, Sopheab H, Phalla T, Leng HB, Mills S, Bennett A, et al. Sexual bridging by Cambodian men: Potential importance for general population spread of STD and HIV epidemics. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2000;27(6):320–326. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200007000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, Mwijarubi E, Klokke A, Senkoro K, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346(8974):530–536. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta GR, Parkhurst JO, Ogden JA, Aggleton P, Mahal A. Structural approaches to HIV prevention. Lancet. 2008;372(9640):764–775. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60887-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Olkin I. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando: Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hedges LV, Vevea JL. Fixed- and random-effects models in meta-analysis. Psychological Methods. 1998;3:486–504. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez AL, Lindan CP, Mathur M, Ekstrand M, Madhivanan P, Stein ES, et al. Sexual Behavior Among Men Who have Sex with Women, Men, and Hijras in Mumbai, India—Multiple Sexual Risks. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9129-z. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh T, Zhang J, Qiang DJ. HIV knowledge and risk behaviour of female sex workers in Yunnan Province, China: Potential as bridging groups to the general population. AIDS Care. 2005;17(8):958–966. doi: 10.1080/09540120500100676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtgrave DR, Crosby RA. Social capital, poverty, and income inequality as predictors of gonorrhoea, syphilis, chlamydia and AIDS case rates in the United States. Sexually transmitted infections. 2003;79(1):62–64. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.1.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Boynton MH, Warren MR, Lacroix JM, Carey MP, Johnson BT. Efficacy of HIV Prevention Interventions in Latin American and Caribbean Nations, 1995–2008: A Meta-Analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9763-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huedo-Medina TB, Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Botella J. Assessing heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Q statistic or I2 index? Psychological Methods. 2006;11(2):193–206. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana S, Singh S. Beyond medical model of STD intervention: lessons from Sonagachi. Indian journal of public health. 1995;39(3):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Eagly AH. Quantitative synthesis of social psychological research. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology. New York, NY US: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 496–528. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey MP. Meta-synthesis of health behavior change meta-analyses. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(11):2193–2198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BT, Scott-Sheldon LA, Huedo-Medina TB, Carey MP. Interventions to reduce sexual risk for human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents: a meta-analysis of trials, 1985–2008. Archives of Pediatric & Adolescent Medicine. 2011;165(1):77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb ML, Fishbein M, Douglas JM, Jr, Rhodes F, Rogers J, Bolan G, et al. Efficacy of risk-reduction counseling to prevent human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted diseases: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280(13):1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.13.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Micro-social structural approaches to HIV prevention: a social ecological perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17(Suppl 1):S102–S113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau KA, Wang B, Saksena NK. Emerging trends of HIV epidemiology in Asia. AIDS Reviews. 2007;9(4):218–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee I, Tan JY. Filial ethics and judgments of filial behavior in Taiwan and the United States. International Journal of Psychology. 2011 doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.616511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim LL International Labour Office. The sex sector : the economic and social bases of prostitution in Southeast Asia. Geneva: International Labour Office; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. Practical Meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Jia M, Ma Y, Yang L, Chen Z, Ho DD, et al. The changing face of HIV in China. Nature. 2008;455(7213):609–611. doi: 10.1038/455609a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narain JP, Lo YR. Epidemiology of HIV-TB in Asia. Indian Journal of Medical Research. 2004;120(4):277–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OPHI. Country briefing: China. Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) at a Glance. Oxford, UK: Oxford Poverty & Human Development Initiative; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Park LS, Siraprapasiri T, Peerapatanapokin W, Manne J, Niccolai L, Kunanusont C. HIV transmission rates in Thailand: evidence of HIV prevention and transmission decline. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;54(4):430–436. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181dc5dad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piot P, Greener R, Russell S. Squaring the circle: AIDS, poverty, and human development. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4(10):1571–1575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudel KC. HIV health delivery in Viet Nam from the viewpoint of the continuum of prevention and care. Storrs, CT: Center for Health, Intervention, and Prevention Lecture Series; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ruxrungtham K, Brown T, Phanuphak P. HIV/AIDS in Asia. Lancet. 2004;364(9428):69–82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16593-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagar AD, Najam A. The human development index: A critical review. Ecological Economics. 1998;25:249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Meca J, Marín-Martínez F, Chacón-Moscoso S. Effect-size indices for dichotomized outcomes in Meta-Analysis. Psychological Methods. 2003;8(4):448–419. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.8.4.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. AIDS. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendeman D, Basu I, Das S, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ. Empowering sex workers in India to reduce vulnerability to HIV and sexually transmitted diseases. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;69(8):1157–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan JY, Huedo-Medina TB, Lennon CA, White AC, Johnson BT. Us versus them in context: Meta-analysis as a tool for geotemporal trends in inter-group relations. International Journal of Conflict Violence. 2010;4(2):288–297. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, W.H.O. 2008 report on the global AIDS epidemic. Geneva: UNAIDS and World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Economic growth and human development, Human Development Report 1996. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human development to eradicate poverty, Human Development Report 1997. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Consumption for human development, Human Development Report 1998. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Globalization with a human face, Human Development Report 1999. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Human rights and human development, Human Development Report 2000. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Making new technologies work for human development, Human Development Report 2001. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Deepening democracy in a fragmented world, Human Development Report 2002. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Millennium development goals: a compact among nations to end human poverty, Human Development Report 2003. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Cultural liberty in today’s diverse world, Human Development Report 2004. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Beyond scarcity: power, poverty and the global water crisis, Human Development Report 2006. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. HIV/AIDS in Asia and the Pacific Region. 2001

References to Reports of Studies Included in Analyses

- Abdullah ASM, Ming CY, Seng CK, Ping CY, Fai CK, Wing FY, et al. Effects of a Brief Sexual Education Intervention of the Knowledge and Attitudes of Chinese Public School Students. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention & Education for Adolescents & Children. 2003;5(3):129–149. [Google Scholar]

- Basu I, Jana S, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Swendeman D, Lee SJ, Newman P, et al. HIV prevention among sex workers in India. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2004;36(3):845. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200407010-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentley ME, Spratt K, Shepherd ME, Gangakhedkar RR, Thilikavathi S, Bollinger RC, et al. HIV testing and counseling among men attending sexually transmitted disease clinics in Pune, India: changes in condom use and sexual behavior over time. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1869–1877. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia V, Swami HM, Parashar A, Justin TR. Condom-promotion programme among slum-dwellers in Chandigarh, India. Public Health. 2005;119(5):382–384. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave G, Lindan CP, Hudes ES, Desai S, Wagle U, Tripathi SP, et al. Impact of an intervention on HIV, sexually transmitted diseases, and condom use among sex workers in Bombay, India. AIDS. 1995;9:S21–S30. (Journal Article) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busza J, Baker S. Protection and participation: An interactive programme introducing the female condom to migrant sex workers in Cambodia. AIDS Care. 2004;16(4):507–518. doi: 10.1080/09540120410001683457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celentano DD, Bond KC, Lyles CM, Eiumtrakul S, Go VFL, Beyrer C, et al. Preventive intervention to reduce sexually transmitted infections: a field trial in the Royal Thai Army. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160(4):535. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HT, Liao Q. A pilot study of the NGO-based relational intervention model for HIV prevention among drug users in China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2005;17(6):503–514. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2005.17.6.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornman DH, Schmiege SJ, Bryan A, Joseph Benziger T, Fisher JD. An information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model-based HIV prevention intervention for truck drivers in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64(8):1572–1584. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng LG, Ding XB, Lv F, Pan CB, Yi HR, Liu HH, et al. [Study on the effect of intervention about acquired immunodeficiency syndrome among men who have sex with men] Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;30(1):18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontanet AL, Saba J, Chandelying V, Sakondhavat C, Bhiraleus P, Rugpao S, et al. Protection against sexually transmitted diseases by granting sex workers in Thailand the choice of using the male or female condom: results from a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1851. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Fajans P, Meliawan P, MacDonald K, Thorpe L. Behavioral interventions for reduction of sexually transmitted disease/HIV transmission among female commercial sex workers and clients in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS. 1996;10(2):213–219. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199602000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Reed BD, Muliawan P, Wolfe R. The Bali STD/AIDS Study: evaluation of an intervention for sex workers. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(1):50. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford K, Wirawan DN, Suastina W, Reed BD, Muliawan P. Evaluation of a peer education programme for female sex workers in Bali, Indonesia. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2000;11(11):731. doi: 10.1258/0956462001915156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford N, Koetsawang S. A pragmatic intervention to promote condom use by female sex workers in Thailand. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1999;77(11):888. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay DN, Chanda M, Sarkar K, Niyogi SK, Chakraborty S, Saha MK, et al. Evaluation of sexually transmitted diseases/human immunodeficiency virus intervention programs for sex workers in Calcutta, India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(11):680. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175399.43457.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilada IS. 'Project Saheli' for sex workers - A replicable model. 2000 Retrieved from http://aidssupport.aarogya.com/index.php/showcasing-initiatives/304-indian-health-organisations-project-saheli-for-sex-workers.

- Jana S, Singh S. Beyond medical model of STD intervention: lessons from Sonagachi. Indian Journal of Public Health. 1995;39(3):125–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawichai S, Beyrer C, Khamboonruang C, Celentano DD, Natpratan C, Rungruengthanakit K, et al. HIV incidence and risk behaviours after voluntary HIV counselling and testing (VCT) among adults aged 19–35 years living in peri-urban communities around Chaing Mai city in northern Thailand, 1999. AIDS Care. 2004;16(1):21–35. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001633949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar MS, Mudaliar S, Daniels D. Community-based outreach HIV intervention for street-recruited drug users in Madras, India. Public Health Reports. 1998;113(Suppl 1):58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Donnell D, Metzger D, Sherman S, Aramrattna A, Davis-Vogel A, et al. The efficacy of a network intervention to reduce HIV risk behaviors among drug users and risk partners in Chiang Mai, Thailand and Philadelphia, USA. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(4):740–748. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JTF, Lau M, Cheung A, Tsui HY. A randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of an Internet-based intervention in reducing HIV risk behaviors among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong. AIDS Care. 2008;20(7):820–828. doi: 10.1080/09540120701694048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JTF, Tsui HY, Cheng S, Pang M. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the relative efficacy of adding voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) to information dissemination in reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among Hong Kong male cross-border truck drivers. AIDS Care. 2010;22(1):12. doi: 10.1080/09540120903012619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Stanton B, Wang B, Mao R, Zhang H, Qu M, et al. Cultural adaptation of the Focus on Kids program for college students in China. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2008;20(1):1–14. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2008.20.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Wang B, Fang X, Zhao R, Stanton B, Hong Y, et al. Short-term effect of a cultural adaptation of voluntary counseling and testing among female sex workers in China: A quasi-experimental trial. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(5):406. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.5.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Dukers N, Van den Hoek A, Yuliang F, Zhiheng C, Jiangting F, et al. Decreasing STD incidence and increasing condom use among Chinese sex workers following a short term intervention: a prospective cohort study. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2002;78(2):110. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.2.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Ang A, Coly A, Tiglao TV. A model HIV/AIDS risk-reduction program in the Philippines: A comprehensive community-based approach through participatory action research. Health Promotion International. 2004;19(1):69–76. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dah109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Chiao C, Stein JA, Malow R. Impact of social and structural influence interventions on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female bar workers in the Philippines. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality. 2005;17(1):45–63. doi: 10.1300/J056v17n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Nguyen C, Ang A, Tiglao TV. HIV/AIDS prevention among the male population: results of a peer education program for taxicab and tricycle drivers in the Philippines. Health Education and Behavior. 2005;32(1):57–68. doi: 10.1177/1090198104266899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morisky DE, Stein JA, Chiao C, Ksobiech K, Malow R. Impact of a social influence intervention on condom use and sexually transmitted infections among establishment-based female sex workers in the Philippines: A multilevel analysis. Health Psychology. 2006;25(5):595–603. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller O, Sarangbin S, Ruxrungtham K, Sittitrai W, Phanuphak P. Sexual risk behaviour reduction associated with voluntary HIV counselling and testing in HIV infected patients in Thailand. AIDS Care. 1995;7(5):567–572. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peak A, Rana S, Maharjan SH, Jolley D, Crofts N. Declining risk for HIV among injecting drug users in Kathmandu, Nepal: the impact of a harm-reduction programme. AIDS. 1995;9(9):1067. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199509000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SG, Sutcliffe C, Srirojn B, Latkin CA, Aramratanna A, Celentano DD. Evaluation of a peer network intervention trial among young methamphetamine users in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripiboon D. A HIV/AIDS prevention program for married women in rural northern Thailand. Australian Journal of Primary Health. 2001;7(3):83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Ubaidullah M. Social vaccine for HIV prevention: a study on truck drivers in South India. Social Work in Health Care. 2004;39(3/4):399. doi: 10.1300/j010v39n03_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Griensven GJ, Limanonda B, Ngaokeow S, Ayuthaya SI, Poshyachinda V. Evaluation of a targeted HIV prevention programme among female commercial sex workers in the south of Thailand. British Medical Journal. 1998;74(1):54. doi: 10.1136/sti.74.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visrutaratna S, Lindan CP, Sirhorachai A, Mandel JS. 'Superstar' and 'model brothel': developing and evaluating a condom promotion program for sex establishments in Chiang Mai, Thailand. AIDS. 1995;9(Suppl 1):S69–S75. (Journal Article) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Keats D. Developing an innovative cross-cultural strategy to promote HIV/AIDS prevention in different ethnic cultural groups of China. AIDS Care. 2005;17(7):874–891. doi: 10.1080/09540120500038314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ML, Chan R, Koh D. Long-term effects of condom promotion programmes for vaginal and oral sex on sexually transmitted infections among sex workers in Singapore. AIDS. 2004;18(8):1195. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong ML, Chan R, Lee J, Koh D, Wong C. Controlled evaluation of a behavioral intervention programme on condom use and gonorrhoea incidence among sex workers in Singapore. Health Education Research. 1996;11(4):423–432. [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Rou K, Jia M, Duan S, Sullivan SG. The first community-based sexually transmitted disease/HIV intervention trial for female sex workers in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S89–S94. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304702.70131.fa. (Journal Article) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiaoming S, Yong W, Choi KH, Lurie P, Mandel J. Integrating HIV prevention education into existing family planning services: results of a controlled trial of a community-level intervention for young adults in rural China. AIDS and Behavior. 2000;4(1):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Xu F, Kilmarx PH, Supawitkul S, Manopaiboon C, Yanpaisarn S, Limpakarnjanarat K, et al. Incidence of HIV-1 infection and effects of clinic-based counseling on HIV preventive behaviors among married women in northern Thailand. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2002;29(3):284. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200203010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Wang J, Zhao N, Chen S, Zhou P. The effectiveness of an intervention program in the promotion of condom use among sexually transmitted disease patients. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;23(3):218–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye XX, Huang H, Li SH, Xu G, Cai Y, Chen T, et al. HIV/AIDS education effects on behaviour among senior high school students in a medium-sized city in China. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2009;20(8):549. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JL, Zhang HB, Wu ZY, Zheng YJ, Xu J, Wang J, et al. HIV risk behavior based on intervention among men who have sex with men peer groups in Anhui province. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;42(12):895–900. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.