Abstract

Recently we reported that BN rats were more resistant to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced myocardial dysfunction than SS rats. This differential sensitivity was exemplified by reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and diminished NFκB pathway activation. To further clarify the mechanisms of different susceptibility of these two strains to endotoxin, this study was designed to examine the alterations of cardiac and mitochondrial bioenergetics, proinflammatory cytokines, and signaling pathways after hearts were isolated and exposed to LPS ex vivo. Isolated BN and SS hearts were perfused with LPS (4 μg/ml) for 30 min in the Langendorff preparation. LPS depressed cardiac function as evident by reduced left ventricular developed pressure as well as decreased peak rate of contraction and relaxation in SS hearts, but not in BN heart. These findings are consistent with our previous in vivo data. Under complex I substrates a higher O2 consumption and H2O2 production were observed in mitochondria from SS hearts than that from BN hearts. LPS significantly increased H2O2 levels in both SS and BN heart mitochondria; however the increase in O2 consumption and H2O2 production in BN heart mitochondria was much lower than that in SS heart mitochondria. Additionally LPS significantly decreased complex I activity in SS hearts but not in BN hearts. Furthermore, LPS induced higher levels of TNF-α and increased phosphorylation of IκB and p65 more in SS hearts than BN hearts. Our results clearly demonstrate that less mitochondrial dysfunction combined with a reduced production of TNF-α and diminished activation of NFκB are involved in the mechanisms by which isolated BN hearts were more resistant to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction.

Keywords: myocardial dysfunction, Brown Norway rats, Dahl S rats, lipopolysaccharide, mitochondria, NFκB pathway, proinflammatory cytokines

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a leading cause of death in adult intensive care units with a mortality rate of 20~60% in the US (1). In septic shock, the cardiovascular functions are disrupted and myocardial depression is one of the manifestations. Myocardial depression by septic shock is characterized by impaired myocardial contractility and reduced ejection fraction (2).

Various molecular mechanisms are involved in septic cardiomyopathy, such as circulating cardiosuppressing mediators, alterations of myocardial calcium homeostasis, nitric oxide (•NO) and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) signaling, as well as mitochondrial dysfunction and myocardial apoptosis. Cardiosuppressing proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-1β, are known to be elevated in the circulation during sepsis, and have been found to directly depress myocardial contractility in vitro (2). Interestingly, TNF-α-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cardiac cells occurs mainly in mitochondria (3). Mitochondria, the power house of the cell, have been shown to play a critical role in the development and manifestations of septic shock in patients with bacterial infection (4). For example, sepsis reduces activities of mitochondrial electron transport chain enzyme complexes in hearts of septic animal (5) and increases mitochondrial production of superoxide (O2˙−) and hydroxyl radicals (6), which in turn inhibits oxidative phosphorylation and ATP generation. Inhibition of oxidative phosphorylation and subsequent depletion of ATP could potentially lead to sepsis-induced organ dysfunction (4).

Brown Norway (BN) rats and Dahl S (SS) rats are important animal models that have been used to study mechanisms of cardiovascular disease by us and other investigators (7–10). BN rats were the first rat strain to have their genome fully sequenced. Thus, studies using BN rats have the potential to provide insight into the genetic basis of responses to physiological and pathophysiological challenges. Likewise, the SS rat genome has recently been sequenced. The SS rat is prone to hypertension, especially when placed on high salt diets; they are also afflicted with a chronic state of oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction (8, 9). Moreover, consomic SS-13BN rats confer protection against high-salt (8) and restores vascular relaxation mechanisms impaired in SS rats (9), presumably by reducing oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in the SS rat. This type of vascular protection in this model could lead to genetic manipulations that would result in reducing the susceptibility of a group of people more prone to hypertension as a result of environmental stressors, i.e. excess salt diet. Similar information could be obtained in our study using the SS and BN rat models in the etiology of septic shock.

Recently we explored the susceptibility to LPS-induced cardiomyopathy and the role of inflammatory signaling in BN and SS rats treated with LPS (20 mg/kg) via intraperitoneal injection for 6 h (11). We found that BN hearts are more resistant to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction than SS hearts in which reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and diminished activation of NFκB pathway are involved (11). To extend our in vivo findings, we sought to examine the direct effects of LPS on the isolated perfused heart models. Cardiac and mitochondrial function and proinflammatory mediators were monitored and recorded. Our results showed that direct administration of LPS to the Langendorff perfused beating heart induced less damage in the BN than in SS rats. This reduced impairment in the BN rats might be attributed to less mitochondrial dysfunction, lower production of TNF-α and decreased activation of NFκB pathway in the myocardium compared to the SS rat.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

LPS was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Antibodies against phospho-p65 (P-p65), p65, phospho-IκB (P-IκB), phospho-extracellular signal-regulated kinase (p-ERK), ERK, phospho-p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (P-p38 MAPK), p38 MAPK and phospho-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (P-JNK) and JNK were from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA). Antibodies against GAPDH were from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA). ELISA development kits for analyzing rat TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Animal model

Eight-week old BN and SS male rats were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). The Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all the animal protocols in this study. All rats used in this study received humane care in compliance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, by the National Research Council.

Langendorff isolated heart preparation and measurements

Rats were maintained in identical housing conditions. Hearts from BN and SS rats were isolated and perfused as previously described (7). Briefly, isolated hearts were perfused with modified Krebs–Henseleit bicarbonate buffer in the Langendorff mode at a constant perfusion pressure of 80 mmHg (7). Perfusate and bath temperatures were maintained at 37.2 ±0.1°C using a thermostatically controlled water circulator (Lauda E100, Lauda Dr. R. Wobser GMBH & CO. KG, Pfarrstraße, Germany). Left ventricular systolic and diastolic pressures were measured with a transducer connected to a thin, saline-filled latex balloon inserted into the left ventricle through the mitral valve from an incision in the left atrium. Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP) was derived from the systolic LVP-diastolic LVP. Data points collected on each heart included LVDP, positive and negative derivative of pressure (+dP/dt and −dP/dt, respectively). Heart rates (in beats/min) were determined by beat-to-beat averages at 30-s intervals. The overflow from the bath used to immerse the heart was collected as coronary flow rate (in ml·min−1). After 30 min stabilization, hearts were subjected to 30 min LPS (4 μg/ml) perfusion followed by 30 min washout. At the end of the experiments, the hearts were removed from the Langendorff apparatus and mitochondria isolated for further determination of mitochondrial bioenergetics (O2 consumption), ROS generation, and some hearts were freeze-clamped and stored at −80°C for later studies.

Isolation of mitochondria

The hearts were quickly immersed in an ice-cold isolation buffer of 200 mM mannitol, 50 mM sucrose, 5 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM EGTA, 5 mM 3-(N-Morpholino)propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) and 0.1% bovine serum albumin (pH 7.2, adjusted with potassium hydroxide). The auricles were removed and the remaining ventricles were minced into ~1 mm3 pieces. The tissue was homogenized with a Teflon pestle (DuPont, Wilmington, DE) for 30 s in the presence of 1 mg/ml protease. This was followed by another 30 s of homogenization. The mitochondria were then isolated by differential centrifugation at 4°C (12). The total protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay with bovine serum albumin as a standard (7).

Measurements of mitochondrial O2 consumption and H2O2 release

O2 consumption and H2O2 generation were measured polarographically at 28°C with a four-channel free radical analyzer (TBR4100, WPI, Sarasota, FL). An aliquot of mitochondria pellets were diluted in 0.5 ml of respiratory buffer (110 mM KCl, 5 mM K2PH4, 10 mM 3-[n-morpholino] propanesulfonic acid, 10 mM Mg-acetate, 1 mM EDTA, 1 M tetrasodium pyrophosphate, 0.1% BSA; pH 7.2) to 0.5 mg of mitochondrial protein/ml. Glutamate/malate (5 mM), complex I substrates or 5 mM succinate, complex II substrate were added to the mitochondrial suspension to initiate state 2 respiration. State 3 respiration was initiated and recorded by the addition of 0.3 mM ADP, and upon depletion of ADP, state 4 respiration was recorded (13). Calibration of O2 and H2O2 electrodes were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (WPI, Sarasota, FL) by using aqueous calibration for oxygen sensor, and 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8 μM standard H2O2 solutions for H2O2 sensor. The calibration curves exhibited a linear correlation coefficient of 0.98 for both sensors.

Enzymatic assay of complex I and II

The rotenone-sensitive complex I (NADH–CoQ reductase) activity was measured in mitochondrial particles obtained by three cycles of freezing and thawing of 1 mg of rat heart mitochondria dissolved in 1 mL of 50 mmol/L phosphate buffer, pH 7.2 (14). The assay mixture 25 mmol/L KPi (pH 7.4), 3 mg/mL BSA, 60 μmol/L decylubiquinone, 160 μmol/L DCIP, 80 μmol/L NADH, 2 μmol/L antimycin and 2 mmol/L KCN was mixed well with heart mitochondria. Complex I activity rate was monitored spectrophotometrically by the decrease in absorbance at 600 nm at 37°C. The rotenone-insensitive complex I activity was determined by measuring a sample with 4 μmol/L rotenone added to the reaction mixture. Rotenone-specific complex I activity was calculated as the total activity minus the rotenone-insensitive activity. Complex II activity was also measured spectrophotometrically at 600 nm (14). The 1 mL incubation buffer for measuring complex II activity contained 80 mmol/L potassium phosphate, 1 g/L BSA, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 0.2 mmol/L ATP, 10 mmol/L succinate, 0.3 mmol/L KCN, 80 μmol/L DCIP, 50 μmol/L decylubiquinone, 1 μmol/L antimycin-A, and 3 μmol/L rotenone, pH 7.8. An aliquot of mitochondrial suspension (final concentration 1 mg/mL) was added to the incubation buffer without KCN and succinate at 37°C. After 10 min, we added KCN and succinate to start the reaction and measured the absorbance at 1-min intervals for 5 min at 37°C. Blanks were measured in the presence of 5 mmol/L malonate that was added before pre-incubation. All above enzyme activity assays were repeated in 9 separate experiments of three replicates each.

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as we previously reported (7). Briefly, hearts were homogenized in lysis buffer and 60 μg of the homogenate was loaded and separated by 12% SDS/PAGE. The separated proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against phospho-p65, p65, phospho-IкB, IкB, phospho-ERK, ERK, phospho-p38 MAPK, p38 MAPK, phospho-JNK, JNK or GAPDH overnight and secondary antibody for 1 hour. Bands of identity were then visualized with Super Signal West Pico kit (Pierce Biotechnology).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Heart tissue was homogenized in ice cold lysis buffer and the supernatant was used for ELISA and protein concentration assay. Levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in heart homogenates were determined by rat specific DuoSet ELISA development kits (R&D Systems) according to the manual. Data are expressed as pg/mg protein of heart tissue.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD or ± SE and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or by two-tailed t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of LPS on myocardial function in isolated BN and SS rat hearts

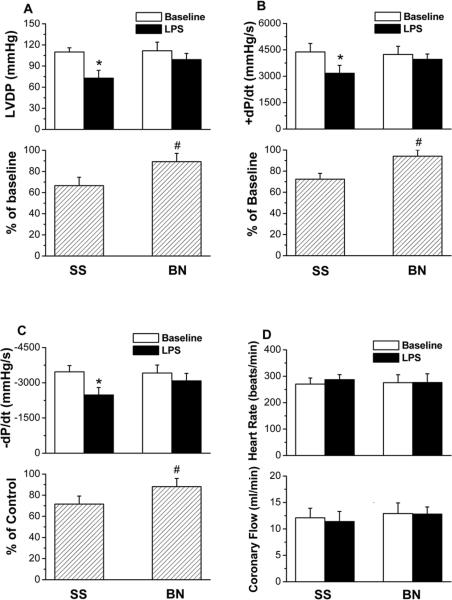

To determine whether the different resistance to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction in BN and SS rat is the same when the hearts from BN and SS rats were directly perfused with LPS ex vivo as in vivo (11), hearts were isolated and perfused with LPS. Left ventricular developed pressure (LVDP), which is systolic minus diastolic pressure, was used to assess myocardial function. There were no differences in basal LVDP (determined after 30 min stabilization time) between the BN and SS rats. However, LPS (4 μg/ml, 30 min) decreased LVDP less in BN rat hearts than in SS rat hearts (Figure 1A upper panel, p<0.05). After LPS, LVDP when expressed as the percentage of baseline value was ~ 20% more in BN rat hearts than in SS rat hearts (Figure 1A low panel, p<0.05). Furthermore, LPS significantly reduced the peak rate of contraction (+dP/dt) and the peak rate of relaxation (−dP/dt) in SS hearts, but not in BN hearts (Figure 1B and 1C, p<0.05). However, LPS did not affect heart rates and coronary flow in either strain (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Differential resistance to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction in isolated BN and SS rat hearts perfused with LPS (4 μg/ml).

(A) LVDP, (B) +dP/dt and (C) −dP/dt, (D) heart rate and coronary flow rate after 30 min perfusion with/without LPS. Values are means ± SD (n=8). *P < 0.05 vs. control group without LPS; #P < 0.05 compared to SS hearts with LPS.

Effects of LPS on mitochondrial O2 consumption and H2O2 release

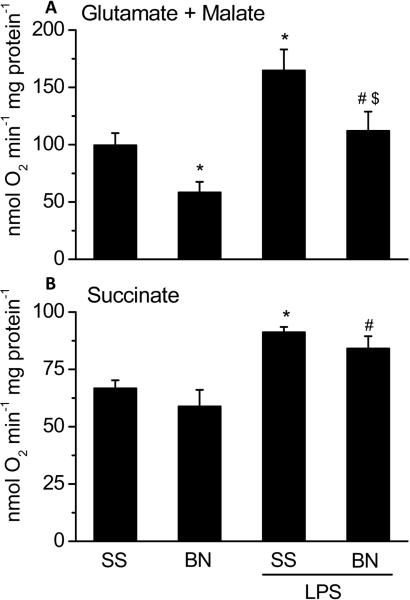

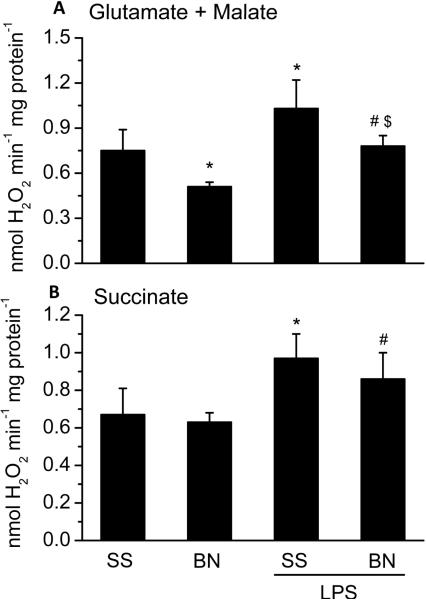

To determine the effects of LPS on mitochondrial function of SS and BN rat hearts, O2 consumption and H2O2 production were determined using freshly isolated mitochondria from BN and SS hearts perfused with LPS or buffer. With complex I substrates (glutamate/malate), a lower O2 consumption and H2O2 production were observed in mitochondria from buffer perfused BN hearts than that from buffer perfused SS hearts (Figures 2 and 3, respectively). With complex II substrate (succinate), there was no difference in basal O2 consumption and H2O2 production in the mitochondria from the two strains (Figure 2 and Figure 3). These results suggest that complex I activity of BN rat hearts is lower than that of SS rat hearts under normal physiological condition. LPS perfusion significantly increased mitochondrial O2 consumption with either complex I (Figure 2A) or complex II substrates (Figure 2B) in both strains of rats. However, with complex I substrates glutamate/malate, the increase in O2 consumption by LPS was lower in mitochondria of BN hearts perfused with LPS than SS hearts perfused with LPS (Figure 2A). In contrast, there were no significant differences in mitochondrial O2 consumption by LPS between the SS and BN hearts with the complex II substrate succinate. LPS-induced H2O2 production was lower in BN hearts than in SS hearts (Figure 3A) with complex I substrates. LPS significantly increased H2O2 levels both in SS and BN rat hearts with complex II substrate succinate (Figure 3B).

Figure 2. Mitochondrial O2 consumption in SS and BN rat hearts perfused with or without LPS (4 μg/ml).

The data are shown as means ± SD (n=8). Panel A shows mitochondrial reaction mixture was added with complex I substrates glutamate/malate; Panel B shows mitochondrial reaction mixture was added with complex II substrate succinate. *P < 0.05 compared to SS control group; #P < 0.05 compared to BN control group; $P < 0.05 compared to SS hearts with LPS.

Figure 3. Mitochondrial H2O2 production in SS and BN rat hearts perfused with or without LPS (4 μg/ml).

The data are shown as means ± SD (n=8). Panel A shows mitochondrial H2O2 production with complex I substrates glutamate/malate and Panel B shows mitochondrial H2O2 production with complex II substrate succinate. *P < 0.05 compared to SS control group; #P < 0.05 compared to BN control group; $P < 0.05 compared to SS hearts with LPS.

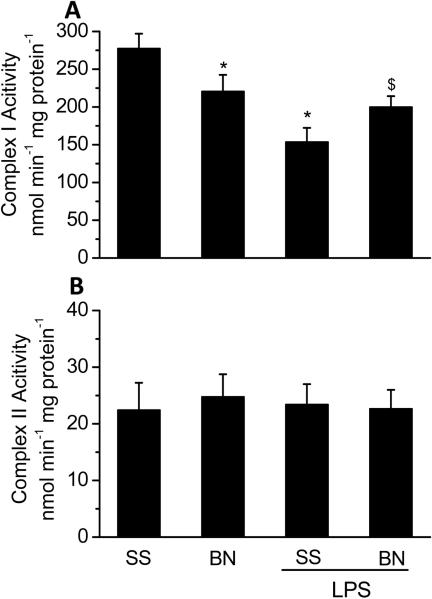

Effects of LPS on complex I and II activity

To determine the underlying mechanisms for the differences in O2 consumption and H2O2 production with different substrates, complex I and II activities were measured. As shown in Figure 4A, basal complex I activity was lower in BN rat hearts than in SS rat hearts (p<0.05). LPS significantly decreased complex I activity in SS rat hearts (~ 50%) but not in BN rat hearts. There were no significant differences in complex II activity between BN and SS rat heart mitochondria and LPS did not affect complex II activity in both strains (Figure 4B). These results supports our observation that complex I activity of the BN rat hearts is less sensitive to LPS than the SS rat hearts.

Figure 4. Complex I and II activities in mitochondria from SS and BN hearts perfused with or without LPS (4 μg/ml).

The data are shown as means ± SD (n=9). *P < 0.05 compared to SS control group; $P < 0.05 compared to SS hearts with LPS.

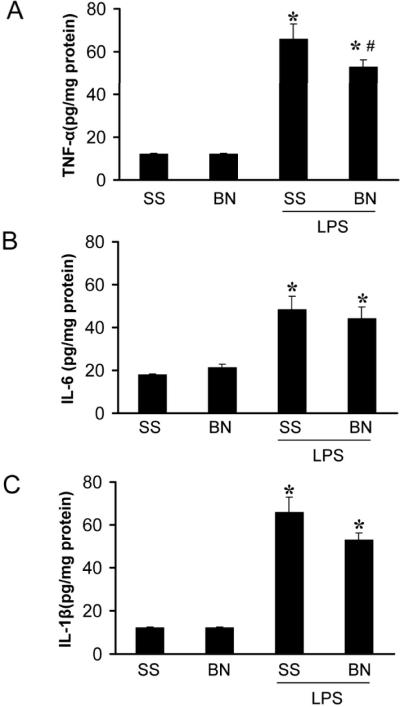

The effects of LPS on the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 in hearts

The basal levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were similar in the hearts of SS or BN rats (Figure 5) ranging from 10 to 20 pg/mg protein. After LPS treatment, the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 were dramatically increased in both SS and BN hearts. However, BN hearts generated lower levels of TNF-α than SS hearts after LPS perfusion (P<0.05, Figure 5A). There was no significant difference in IL-1β and IL-6 levels stimulated by LPS between these two strains although IL-1β tended to be lower in BN hearts (Figure 5B and 5C). These data indicate that lower TNF-α induction may mediate the increased tolerance of BN hearts against LPS.

Figure 5. Levels of inflammatory cytokines in SS and BN rat hearts perfused with or without LPS (4 μg/ml).

Isolated hearts were treated with LPS for 30 minutes. Heart homogenates from SS and BN rats were assayed for TNF-α, IL1-β and IL-6 by ELISA. Values are means ± SD (n=7). (A) TNF-α, (B) IL1-β and (C) IL-6. *P < 0.05 vs. control without LPS, and #P < 0.05 vs. SS hearts with LPS.

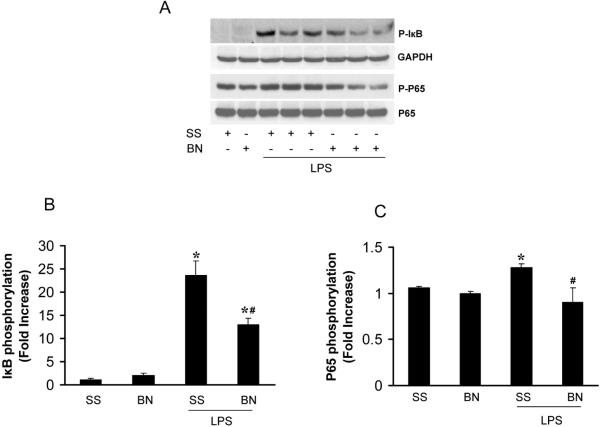

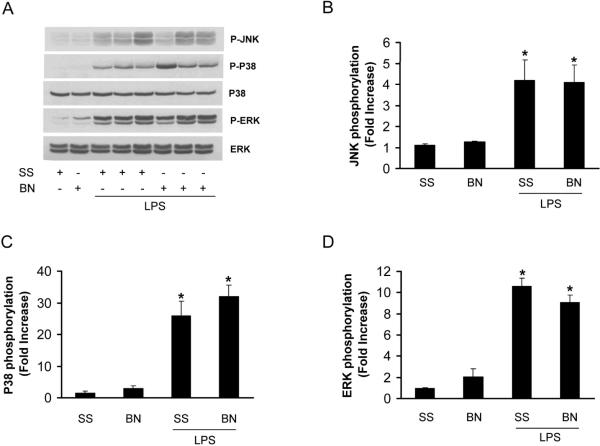

The effects of LPS on the activation of NFκB and MAPK in hearts

We previously demonstrated that NFκB activation was much lower in hearts from BN rats with LPS in vivo treatment than that from SS rats (11). To determine whether NFκB is activated in the isolated heart perfused directly by LPS, we measured the phosphorylation of IκB and p65, two important components in NFκB pathway. IκB phosphorylation was elevated significantly in LPS perfused hearts (30 min) from either SS or BN rats, however, the phosphorylation of IκB was about 50% less in BN rat hearts than SS rat hearts perfused with LPS (Figure 6A, 6B). LPS also elevated p65 phosphorylation significantly in SS rat hearts compared to BN rat hearts (Figure 6C). Mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway including ERK, JNK and p38 MAPK are important signaling pathways regulating TNF-α production in endotoxemia (15). LPS significantly increased the phosphorylation of JNK, ERK and p38 MAPK in both SS and BN rats and there was no significant difference in the increase in phosphorylation of these kinases between the two rat strains (Figure 7). These results suggest that NFκB, but not MAPK pathway, is involved in the mechanisms of increased resistance of BN hearts against LPS toxicity when compared to the SS hearts.

Figure 6. LPS activation of NFκB pathway in hearts after 30 min LPS treatment.

The isolated hearts were processed for western blot analysis. Values are means ± SE (n=5). The blots were probed with antibodies against (A) P-IκB, GAPDH, P-p65 and p65. The densitometry of (B) P-IκB and (C) P-p65 were normalized by GAPDH or p65 and expressed as fold increase over SS hearts without LPS treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. control without LPS, and #P < 0.05 vs. SS hearts with LPS.

Figure 7. LPS activation of MAPK in the heart.

Values are means ± SE (n=5). (A) The representative immunoblots are obtained by incubating with antibodies specific against P-JNK, P-p38, p38, P-ERK and ERK. The densitometry data were normalized with the total ERK or p38 and expressed as fold increase over SS hearts without LPS treatment. (B) JNK phosphorylation; (C) p38 phosphorylation; (D) ERK phosphorylation.

DISCUSSION

Recently we reported that LPS, a critical physiological stressor which is increased in sepsis, impacts myocardial function in BN and SS rats in different ways (11). Our current study is an extension of our previous report (11). In the present study we further unravel the mechanisms underlying the differential responses to LPS in hearts from the SS and BN strains. Our studies show that BN rat differs from the SS rat in both its in vivo and in vitro myocardial responses to LPS. These differences in susceptibility could be related to chronic increases in oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in SS compared to BN rats (8, 9). Interestingly, oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction have been implicated, as well, in the pathogenesis of sepsis during septic shock (16, 17). These observations could have significant clinical implications for the use of SS vs. BN rats. For instance, oxidative stress and vascular compromise in salt sensitive hypertensive patient could lead to worsening outcome during sepsis when compared to the non-hypertensive patient. It is therefore conceivable that use of genetic animal models, like the SS and BN rats, will provide insights into our understanding of some diseases that could otherwise not be attained by other experimental models. In the case of sepsis, the results obtained here are clinically relevant and could herald a new way of portraying the differential susceptibility of patients of different preexisting conditions, for example, salt sensitive hypertensive patients, to sepsis.

It has been reported that LPS directly inhibits cardiac contractility ex vivo in isolated hearts (18). In our previous study, we showed that intraperitoneal injection of LPS decreased left ventricular developed pressure less in the BN rat than in the SS rat (11). In the present study, acute administration of LPS (4 μg/ml) for 30 min depressed basal cardiac function in the isolated SS rat hearts but not in the BN rat hearts. These observations confirm our previous findings (11) that the BN rat is more resistant to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction than the SS rat. It is worth noting, though, that the magnitude of depression of cardiac function in the isolated SS rat hearts is less than our previous in vivo model in similar SS rats in which LPS was injected intraperitoneally (11). This difference in cardiodepression may be due to the high production of systemic proinflammatory cytokines after in vivo LPS treatment that exerted additional depression of cardiac function. There was no reduction of coronary flow in both SS and BN rat hearts (Figure 1D) indicating that the concentration of LPS used in this study does not affect the coronary artery endothelial function.

Several recent reports have demonstrated the effects of LPS on cardiac mitochondrial function. In vivo studies have shown that after the administration of LPS there were marked reductions in cardiac mitochondrial state 3 respiration and ATP synthesis rate (5). A previous work in a rat septic model has also shown that mitochondria isolated from heart muscle exhibit impaired respiration due to inhibition of electron transfer and oxidative phosphorylation by LPS (19). A recent study by Vanasco et al showed that in an acute rat model of endotoxemia, O2 consumption was increased by 30% while state 3 mitochondrial respiration rate was impaired in mitochondria from liver, diaphragm and heart (20). In this septic model, only complex I activity in heart and diaphragm, and complex IV activity in diaphragm were impaired (20). The effect of LPS on mitochondrial function observed in our current study in the isolated perfused heart model is consistent with the study by Vanasco et al. (20). We have found that LPS significantly increased O2 consumption with either complex I or complex II substrates. However, with complex I substrates glutamate/malate, O2 consumption was lower in mitochondria of BN rat hearts with or without LPS treatment than in mitochondria obtained from SS rat hearts. There were no differences in O2 consumption between BN and SS rat heart mitochondria with complex II substrates. We also found complex I activity of BN rat hearts less depressed by LPS than SS rat hearts. Our results clearly show LPS caused more functional damage to mitochondria in the SS rat hearts than in the BN rat hearts. This impairment could be partially attributed to reduced activity of complex I of the respiratory chain. Further studies are required to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the interplay between mitochondrial respiration and the reduction of complex I activity, as well as free radical generation in in vivo conditions.

H2O2 production increased in both SS and BN rat heart mitochondria after LPS treatment, although the production in SS rat heart was significantly higher than in the BN rat hearts with the substrates glutamate/malate. Several mechanisms could explain the increased H2O2 production in this study. One possible mechanism is related to increased O2˙− generation and increased Mn-SOD activity as reported by other investigators (21). Dysfunction of mitochondria caused by sepsis could also increase O2˙− and H2O2 significantly. The LPS-induced mitochondrial H2O2 production in our study may result from an increase in O2˙− anion due to the irreversible inhibition of complex I by LPS. Complex I is a major source of ROS during endotoxiema (LPS exposure). Therefore, a decrease in complex I activity, which signifies damage to the protein complex leads to a “bottle neck” in the complex during electron transfer and electron leakage could ensue (22), which leads to further ROS production. Coupled with loss of GSH during LPS exposure (22), the consequence would be increased ROS emission, which propagates into a vicious cycle of ROS-induced ROS release and further damage t o mitochondria. Subsequent damage to mitochondrial lipids and proteins may contribute to “leaky” (H+ leak) and uncoupled mitochondria (23). Furthermore, O2˙− has also been proposed to act as a protonophore by protonation to HO2˙, which can cross the membrane (23). O2˙− from complex I may also act locally to stimulate H+ leak (24). The net effect of H+ leak is to stimulate respiration (electron transfer) at the expense of oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (24). It has been suggested that in the uncoupled mitochondria, some of the extra respiration caused by O2˙− may be due to O2 consumption by the O2˙− generating system (23). Therefore, with impaired OXPHOS as a consequence of LPS effect (25), it is conceivable that the increase in O2 consumption, mostly to generate O2˙−, could be ascribed to an uncoupled respiration. This notion of uncoupling is also consistent with the observation that LPS reduced OXPHOS in mitochondria and induced a decrease in state 3 respiration, without a change in state 4 respiration (reduced respiratory control index). Ironically, uncoupling is associated with depolarization of mitochondria, which may lead to diminished ROS production. However, the finding that we observed an increased emission of ROS suggests that the fast electron flow under the uncoupled state with a defect in OXPHOS and impaired complex I support more radicalization of O2. Indeed, reducing LPS-induced electron leak from mitochondria with ROS scavengers have been shown to improve electron transfer, to improve ATP synthesis and to improve mitochondrial coupling (26). This may explain the discrepancy we observed between an increase in oxygen consumption and a decrease in complex I activity in response to LPS treatment.

Thus the lower activity of complex I during LPS treatment can account for the enhanced production of H2O2. However, a recent study by Kozlov et al shows that ROS generation did not significantly increase from LPS-treated rat hearts compared with the control rat hearts after 16 hours in an in vivo model with LPS intraperitoneal injection (27). The authors suggested that there might be a ROS-independent mechanism affecting mitochondrial function with LPS treatment in rat heart mitochondria. It is worth noting that the differences in ROS generation in the study by Kozlov et al. (27) and our current study may be attributed to the different phases of endotoxic shock. It has been suggested that mitochondria respond to endotoxemia in a biphasic manner, with an initial increase in respiration followed by a decline (28). The decrease in ROS release in the Kozlov study can be explained by the removal of damaged mitochondria and damaged cells by mitophagy and autophagy, during the 16 hours of LPS treatment. This way, the damaged mitochondria are cleared from the organs or new mitochondria are produced after LPS treatment (29). Excess •NO is an important player in septic shock and it is thought to be a proximal mediator of the inflammatory cascade and it exerts inhibitory effects on mitochondria. Among the deleterious effects of excess •NO generated during sepsis is inhibition and modulation of respiratory complexes, which leads to ROS production (30). The adverse effects of •NO might also, in part, be related to the generation of the deleterious reactive nitrogen species, ONOO−, from the reaction between •NO and O2˙− (30). ONOO− may block complex I, II and III (30), this way it could lead to mitochondrial dysfunction.

Inflammatory cytokines are crucial in endotoxin-induced myocardial dysfunction. Cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6), •NO and prostanoids are the major factors mediating cardiac depression. TNF-α is mainly derived from activated macrophages, cardiomyocytes (31) and cardiac fibroblasts after LPS stimulation (32). Our previous study showed that the response of TNF-α production to LPS stimulation was blunted in BN rat hearts and plasma (11). This blunted cytokine response may be responsible for a better outcome after LPS. In our present study, isolated BN rat hearts when compared to SS rat hearts produced less TNF-α, while IL-6 and IL-1β production did not differ in both strains. This suggests that lower TNF-α induction mediates the resistance of BN rat hearts against LPS. However, we could not exclude the possibility that IL-1β also contributes to the resistance since IL-1β tended to be lower in BN rats after LPS (Figure 5).

NFκB is also an important regulator of immune response to infection. Indeed, incorrect regulation of NFκB has been linked to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases and septic shock. A recent study showed that selective blockade of endothelial-intrinsic NFκB pathway is sufficient to abrogate the cascades of molecular events that lead to septic shock and septic vascular dysfunction, demonstrating a pivotal role of endothelial-specific NFκB signaling in the pathogenesis of septic shock and septic vascular dysfunction (17). We previously demonstrated that LPS-induced NFκB activation was much lower in BN rats than in SS rats (11). In the present study we found that IκB and p65 phosphorylation were activated more in SS rat hearts than in BN hearts (Figure 6) suggesting that less activation of NFκB pathway might be involved in the resistance to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction in the BN rat hearts.

The MAPK signaling cascades are critical for many processes in the immune response. ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK are important signaling pathways downstream of NADPH oxidase in the regulation of TNF-α expression induced by LPS in cardiomyocytes (33). We showed LPS-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, JNK and p38 MAPK in both SS and BN rat hearts, but there were no significant differences between the two rat strains. Thus we propose that NFκB, but not MAPK pathway, is involved in the increased resistance of BN rat hearts to LPS-induced dysfunction.

We are aware of the limitations of the experimental model used in this study. There are three major models currently used to study sepsis. The one we used in this study is the endotoxiema model (LPS). The other two models are the bacterial infection and the host-barrier disruption models. For each model there are advantages and disadvantages in studying sepsis as it relates to the human clinical situation. The LPS model is simple, sterile, and has some similarities to human sepsis. For example, the LPS model is based on the fact that the clinical features of sepsis are caused by the host response, but not the intact pathogen per se. Secondly, the hematological alterations in LPS model are similar to the pathophysiological responses in septic patients (34). Thirdly, LPS induces proinflammatory cytokine expressions in serum (11), parallel to septic patients, whose elevated cytokine levels are associated with severity of the disease (35). However, salient disadvantages of the LPS model are that the transient increases in inflammatory mediators is more intense than in human sepsis, and this animal model is not able to replicate human variability and comorbidity in septic patients. Thus the results obtained from the LPS model may be limited in their translational aspect to the human patients. At the same time, the LPS model is still a widely used experimental model and may represent an important tool to dissect the underlying mechanisms of sepsis.

In summary, the current study extends our previous findings and reveals that less mitochondrial dysfunction combined with a reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and diminished activation of NFκB pathway collectively contribute to the enhanced resistance of isolated hearts from BN rats to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction compared to that from SS rats. This additional finding provides a clear mechanism by which BN rats are more resistant to endotoxemia induced myocardial dysfunction. This study may help elucidate the mechanisms of LPS mediated cell injury and provides new insight into the understanding of septic shock induced cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kirkwood A. Pritchard for his scientific suggestions that helped improve our paper.

This study was supported by grant HL080468 (to Y. S.) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland and fund from Children's Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heron M. Deaths: leading causes for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56(5):1–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flierl MA, Rittirsch D, Huber-Lang MS, Sarma JV, Ward PA. Molecular events in the cardiomyopathy of sepsis. Mol Med. 2008;14(5–6):327–36. doi: 10.2119/2007-00130.Flierl. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corda S, Laplace C, Vicaut E, Duranteau J. Rapid reactive oxygen species production by mitochondria in endothelial cells exposed to tumor necrosis factor-alpha is mediated by ceramide. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24(6):762–8. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RJ. Mitochondrial dysfunction, bioenergetic impairment, and metabolic down-regulation in sepsis. Shock. 2007;28(1):24–8. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000235089.30550.2d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trumbeckaite S, Opalka JR, Neuhof C, Zierz S, Gellerich FN. Different sensitivity of rabbit heart and skeletal muscle to endotoxin-induced impairment of mitochondrial function. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268(5):1422–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor DE, Ghio AJ, Piantadosi CA. Reactive oxygen species produced by liver mitochondria of rats in sepsis. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316(1):70–6. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An J, Du J, Wei N, Xu H, Pritchard KA, Jr., Shi Y. Role of tetrahydrobiopterin in resistance to myocardial ischemia in Brown Norway and Dahl S rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(5):H1783–91. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00364.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cowley AW, Jr., Roman RJ, Kaldunski ML, Dumas P, Dickhout JG, Greene AS, et al. Brown Norway chromosome 13 confers protection from high salt to consomic Dahl S rat. Hypertension. 2001;37(2 Part 2):456–61. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.2.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drenjancevic-Peric I, Phillips SA, Falck JR, Lombard JH. Restoration of normal vascular relaxation mechanisms in cerebral arteries by chromosomal substitution in consomic SS.13BN rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289(1):H188–95. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00504.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi Y, Hutchins W, Ogawa H, Chang CC, Pritchard KA, Jr., Zhang C, et al. Increased resistance to myocardial ischemia in the Brown Norway vs. Dahl S rat: role of nitric oxide synthase and Hsp90. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38(4):625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Du J, An J, Wei N, Guan T, Pritchard KA, Jr., Shi Y. Increased resistance to LPS-induced myocardial dysfunction in the Brown Norway rats versus Dahl S rats: roles of inflammatory cytokines and nuclear factor kappaB pathway. Shock. 2010;33(3):332–6. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b7819e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aldakkak M, Stowe DF, Cheng Q, Kwok WM, Camara AK. Mitochondrial matrix K+ flux independent of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opening. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298(3):C530–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00468.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haumann J, Dash RK, Stowe DF, Boelens AD, Beard DA, Camara AK. Mitochondrial free [Ca2+] increases during ATP/ADP antiport and ADP phosphorylation: exploration of mechanisms. Biophys J. 2010;99(4):997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen AJ, Trijbels FJ, Sengers RC, Smeitink JA, van den Heuvel LP, Wintjes LT, et al. Spectrophotometric assay for complex I of the respiratory chain in tissue samples and cultured fibroblasts. Clin Chem. 2007;53(4):729–34. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.078873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peng T, Zhang T, Lu X, Feng Q. JNK1/c-fos inhibits cardiomyocyte TNF-alpha expression via a negative crosstalk with ERK and p38 MAPK in endotoxaemia. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;81(4):733–41. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huet O, Dupic L, Harrois A, Duranteau J. Oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction during sepsis. Front Biosci. 2011;16(0):1986–95. doi: 10.2741/3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding J, Song D, Ye X, Liu SF. A pivotal role of endothelial-specific NF-kappaB signaling in the pathogenesis of septic shock and septic vascular dysfunction. J Immunol. 2009;183(6):4031–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grandel U, Fink L, Blum A, Heep M, Buerke M, Kraemer HJ, et al. Endotoxin-induced myocardial tumor necrosis factor-alpha synthesis depresses contractility of isolated rat hearts: evidence for a role of sphingosine and cyclooxygenase-2-derived thromboxane production. Circulation. 2000;102(22):2758–64. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies NA, Cooper CE, Stidwill R, Singer M. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration during early stage sepsis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;530(0):725–36. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0075-9_73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vanasco V, Cimolai MC, Evelson P, Alvarez S. The oxidative stress and the mitochondrial dysfunction caused by endotoxemia are prevented by alpha-lipoic acid. Free Radic Res. 2008;42(9):815–23. doi: 10.1080/10715760802438709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dirami G, Massaro D, Clerch LB. Regulation of lung manganese superoxide dismutase: species variation in response to lipopolysaccharide. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(5 Pt 1):L705–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suliman HB, Welty-Wolf KE, Carraway M, Tatro L, Piantadosi CA. Lipopolysaccharide induces oxidative cardiac mitochondrial damage and biogenesis. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;64(2):279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brookes PS. Mitochondrial H(+) leak and ROS generation: an odd couple. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38(1):12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stowe DF, Camara AK. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production in excitable cells: modulators of mitochondrial and cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(6):1373–414. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crouser ED. Mitochondrial dysfunction in septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Mitochondrion. 2004;4(5–6):729–41. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, Wu F, Liu Y, Zhang T. The Effect of Melatonin on Mitochondrial Function in Endotoxemia Induced by Lipopolysaccharide. Asian-Aust J Anim Sci. 2011;24(6):10. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlov AV, Staniek K, Haindl S, Piskernik C, Ohlinger W, Gille L, et al. Different effects of endotoxic shock on the respiratory function of liver and heart mitochondria in rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290(3):G543–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00331.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer M, De Santis V, Vitale D, Jeffcoate W. Multiorgan failure is an adaptive, endocrine-mediated, metabolic response to overwhelming systemic inflammation. Lancet. 2004;364(9433):545–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16815-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suliman HB, Carraway MS, Piantadosi CA. Postlipopolysaccharide oxidative damage of mitochondrial DNA. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(4):570–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200206-518OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Suliman HB, Babiker A, Withers CM, Sweeney TE, Carraway MS, Tatro LG, et al. Nitric oxide synthase-2 regulates mitochondrial Hsp60 chaperone function during bacterial peritonitis in mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48(5):736–46. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wagner DR, Combes A, McTiernan C, Sanders VJ, Lemster B, Feldman AM. Adenosine inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced cardiac expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res. 1998;82(1):47–56. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokoyama T, Sekiguchi K, Tanaka T, Tomaru K, Arai M, Suzuki T, et al. Angiotensin II and mechanical stretch induce production of tumor necrosis factor in cardiac fibroblasts. Am J Physiol. 1999;276(6 Pt 2):H1968–76. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peng T, Lu X, Feng Q. Pivotal role of gp91phox-containing NADH oxidase in lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression and myocardial depression. Circulation. 2005;111(13):1637–44. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160366.50210.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Remick DG, Newcomb DE, Bolgos GL, Call DR. Comparison of the mortality and inflammatory response of two models of sepsis: lipopolysaccharide vs. cecal ligation and puncture. Shock. 2000;13(2):110–6. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200013020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waage A, Halstensen A, Espevik T. Association between tumour necrosis factor in serum and fatal outcome in patients with meningococcal disease. Lancet. 1987;1(8529):355–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91728-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]