Abstract

Numerous studies indicate that social dysfunction is associated with negative symptoms of schizophrenia during the chronic phase of illness. However, it is unclear whether social abnormalities exist during the premorbid phase in people who later develop schizophrenia with prominent negative symptoms, or whether social functioning becomes progressively worse in these individuals from childhood to late adolescence. The current study examined differences in academic and social premorbid functioning in people with schizophrenia meeting criteria for deficit (i.e., primary and enduring negative symptoms) (DS: n=74) and non-deficit forms of schizophrenia (ND: n=271). Premorbid social and academic functioning was assessed for childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence developmental periods on the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS). Results indicated that both DS and ND participants showed deterioration in social and academic functioning from childhood to late adolescence. However, while ND schizophrenia demonstrated greater deterioration of academic compared to social premorbid functioning from childhood to late adolescence, the DS group exhibited comparable deterioration across both premorbid domains, with more severe social deterioration than the ND group. Findings suggest that people with DS show poorer social premorbid adjustment than those with ND as early as childhood, and are particularly susceptible to accelerated deterioration as the onset of schizophrenia becomes imminent. Thus, poor premorbid social adjustment and significant social deterioration from childhood to adolescence may be a hallmark feature of people who later go on to develop prominent negative symptoms and a unique marker for the DS subtype of schizophrenia.

Keywords: Schizophrenia, Deficit Syndrome, Negative Symptoms, Premorbid Adjustment, Social, Academic

1. Introduction

Impairments in premorbid functioning are present well before the onset of the schizophrenia, and are consistent with neurodevelopmental hypotheses of the disorder (Murray et al., 1992; Weinberger, 1995). Evidence for premorbid abnormalities is substantial, and documented using prospective longitudinal approaches, as well as retrospective cohort analyses, retrospective review of academic and other records of individuals currently diagnosed with schizophrenia, and interviews with patients and their relatives that gather information regarding behaviors prior to the schizophrenia prodrome. Using these and other approaches, premorbid abnormalities have been reported for academic and social functioning (Allen et al., 2001, 2005; Reichenberg et al., 2002; Schiffman et al., 2004), motor and intellectual abilities (Caspi et al., 2003; Marcus et al., 1993; Rosso et al., 2000; Schiffman et al., 2004, 2009; Walker, 1994; Walker et al., 1996), and affective responsivity (Walker et al., 1996).

People with schizophrenia meeting criteria for the deficit syndrome (DS) have particularly severe impairment in premorbid functioning (Kirkpatrick et al., 1996; Buchanan et al., 1990; Fenton & McGlashan, 1994; Galderisi et al., 2002). DS is a putative schizophrenia subtype characterized by primary and enduring negative symptoms. It differs from nondeficit (ND) schizophrenia in a number of ways, including course, risk factors, treatment response, neurobiological correlates, emotion perception, and premorbid functioning (see Kirkpatrick et al., 2001, Kirkpatrick and Galderisi, 2008, Cohen et al., 2010; Strauss et al., 2010). Although individuals with DS have poorer premorbid function than ND schizophrenia, previous studies defined premorbid functioning in broad terms or failed to use established scales to assess premorbid functioning, and so it is unclear whether certain aspects of premorbid functioning are differentially impaired among DS and ND patients.

Studies have drawn a distinction between academic and social premorbid functioning (Allen et al., 2001; Cannon et al., 1997; Mukherjee et al., 1991; van Kammen et al., 1994), and this distinction may be particularly relevant to understanding premorbid differences between DS and ND sub-types, given that people with the DS demonstrate enduring deficits in social functioning. There is evidence for a differential decline in social and academic domains, with a steeper decline occurring for academic compared to social functioning, particularly as onset of schizophrenia approaches (Allen et al., 2005; Monte et al., 2008). Importantly, these studies did not consider whether prominent negative symptoms that are evidenced after onset of schizophrenia and impair social functioning were associated with impairments in premorbid social adjustment. However, Carpenter and colleagues (1988) contend that diminished social drive may be evident prior to onset among those who later develop DS. Additionally, perhaps the most striking characteristic of DS in adulthood is low social drive. Individuals with DS display indifference toward others, prefer to be alone, fail to initiate social contact, do not feel lonely, and typically only engage in social activity when prompted to do so. In contrast, while somewhat diminished, social drive is typically more preserved in those individuals whose negative symptoms are due to secondary causes. These individuals may evidence social withdrawal due to suspiciousness, depression, or in an effort to decrease the intensity of external or internal stimuli, but they typically retain interest in other people and think about them often (sometimes to an extent that is pathological). In contrast to social functioning, little evidence supports differences in educational attainment in ND and DS schizophrenia, even in cases where neuropsychological differences between groups are reported (Bryson et al., 2001; Buchanan et al., 1994; Cohen et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2008). While DS patients have somewhat lower years of education obtained, these differences are not typically significant, and generally vary by less than a year. Thus, the pattern of social functioning in persons with DS from childhood to the onset of schizophrenia is unclear, although differential patterns of academic and social decline would be expected, and may provide insight into neurodevelopmental processes that distinguish DS and ND forms of schizophrenia.

The current study examined differences in premorbid academic and social functioning between people with DS and ND schizophrenia using the Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS: Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982). Based upon previous factor analytic studies of the PAS (Allen et al., 2001; Cannon et al., 1997; van Kammen et al., 1994), academic and social premorbid differences were examined from childhood through late adolescence. We hypothesized that people with DS would show greater severity of premorbid social adjustment abnormalities than people with ND schizophrenia, and that social impairments would increase from childhood through late adolescence. Differences were not expected between the two groups on premorbid academic adjustment, although both groups were predicted to show deterioration in academic functioning from childhood to late adolescence.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

There were 345 participants (216 outpatients, 129 inpatients) who met DSM-III or DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia (n=308) or schizoaffective disorder (n=37). Outpatients were recruited from the outpatient clinics of the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center (MPRC) and local area clinics that serve as research recruitment sites. Inpatients were recruited from the Treatment Research Program unit of the MPRC. Participants were divided into DS (n=74) and ND (n=271) groups using the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS), which has good reliability and validity (Kirkpatrick et al., 1989). The deficit classification was made by one of the SDS authors (BK or RWB) or clinicians who were trained to meet reliability standards by one of these authors. To ensure validity of the SDS classification, treatment providers and staff (e.g., psychiatrists, therapists) were consulted and psychiatric charts were reviewed to verify stability of negative symptom presentation and accuracy of the primary vs. secondary distinction. All 37 of the patients diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder were in the ND group, as would be expected since prominent affective symptoms are generally considered secondary sources of negative symptoms that preclude DS categorization1.

Demographic and clinical data are presented for the DS and ND participants in Table 1. One-way ANOVAs and chi-square analyses indicated that the groups did not significantly differ on age, years of education, age of onset, sex, marital status, or race. DS had a lower severity of positive symptoms as indicated by significant differences for the SAPS total score (p=.03), although they did not significantly differ on the hallucinations, bizarre behavior, or thought disorder global scores. Additionally, the DS participants had greater severity of negative symptoms on all 6 SDS domains, as would be expected. The clinical and demographic characteristics of the DS and ND groups were thus consistent with published work on deficit schizophrenia, and suggest that the participants identified as DS and ND in this study validly represent the original conceptualization of these groups (Carpenter et al., 1988; Kirkpatrick et al., 2001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Deficit and Nondeficit Patients

| Deficit (n = 74) | Non-Deficit (n = 271) | Test Statistic | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.4 (9.8) | 37.4 (9.6) | F = 0.01 | p = 0.99 |

| Education | 12.4 (2.3) | 12.7 (2.0) | F = 0.93 | p = 0.34 |

| Age of Onset | 24.0 (5.5) | 24.9 (6.3) | F = 1.17 | P = 0.28 |

| % Male | 74.3% | 62.7% | χ2 = 3.44 | p = 0.063 |

| % Never Married | 83.8% | 69.7% | χ2 = 6.45 | p = 0.09 |

| Race | χ2 = 2.55 | p = 0.64 | ||

| Asian | 4.1% | 1.5% | ||

| African-American | 40.5% | 42.1% | ||

| Mixed-race | 0.0% | 0.7% | ||

| Other-race | 2.7% | 3.3% | ||

| White | 52.7% | 52.4% | ||

| SAPS | ||||

| Hallucinations | 1.64 (1.89) | 2.06 (1.90) | F = 1.72 | p = 0.19 |

| Delusions | 1.89 (1.62) | 2.50 (1.66) | F = 4.88 | p = 0.03 |

| Bizarre Behavior | 0.70 (1.09) | 0.72 (1.06) | F = 0.01 | p = 0.95 |

| Thought Disorder | 0.64 (1.20) | 1.00 (1.26) | F = 3.02 | p = 0.08 |

| Total | 18.14 (19.11) | 25.56 (20.69) | F = 4.65 | p = 0.03 |

| SDS | ||||

| Restricted Affect | 2.31 (0.95) | 0.88 (1.44) | F = 67.65 | p < 0.001 |

| Diminished Emotion | 2.26 (1.06) | 0.73 (1.38) | F = 77.67 | p < 0.001 |

| Poverty of Speech | 2.18 (1.03) | 0.55 (1.38) | F = 89.06 | p < 0.001 |

| Curbed Interests | 2.53 (0.80) | 0.83 (1.43) | F = 95.23 | p < 0.001 |

| Sense of Purpose | 2.81 (0.82) | 0.92 (1.51) | F = 106.95 | p < 0.001 |

| Social Drive | 2.73 (0.90) | 0.90 (1.47) | F = 103.46 | p < 0.001 |

Note. SAPS = Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms; SDS = Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome

Onset of schizophrenia was defined as the time at which full criteria for schizophrenia were met according to the DSM that was in use at this time, as established using the Structure Clinical Interview for DSM diagnoses. The prodrome was defined as the presence of symptoms that definitively met criteria for one of the Criteria A symptoms for schizophrenia (hallucinations, delusions, disorganization, catatonia, negative symptoms). For the current study, individuals exhibiting prodromal symptoms of schizophrenia during the early or late adolescent developmental periods were excluded, regardless of when the first episode of schizophrenia occurred. Only individuals with an age of onset after age 19 were included. The current study did not include data collected for the adulthood period, because many participants were in the prodromal phase of the illness by early adulthood and were exhibiting symptoms that definitively met criteria for one of the Criteria A symptoms for schizophrenia. Additionally, only subjects with complete data for each developmental period were included.

2.2. Procedure

Participants were evaluated with a battery of measures as part of their index admission into the MPRC, from the years 1988 to 2010. The battery consisted of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM, demographic and clinical history interviews, a family history interview, functional outcome measures, symptom interviews, neuropsychological tests, and the Cannon-Spoor Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS; Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982), which was the focus of the current investigation. This is the first comprehensive report of premorbid adjustment data concerned with deterioration across the age periods on social and academic domains from this large archival dataset.

2.3. Measures

The PAS was used to evaluate premorbid social and academic functioning (Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982). The PAS assesses premorbid functioning during childhood (up to 11 years), early adolescence (12 to 15 years), late adolescence (16 to 18 years), and adulthood (19 years and above). Five domains are assessed from childhood to late adolescence, including 1) sociability and withdrawal, 2) peer relationships, 3) scholastic performance, 4) adaptation to school, and 5) social-sexual functioning (social-sexual functioning is not assessed during childhood). Ratings are made on a 0 to 6 point scale, with 0 indicating normal adjustment and 6 indicating severe impairment. The PAS defines “premorbid” as the period ending six months prior to the first episode. Ratings are then averaged across each of the domains, to obtain individuals scores for the childhood, early adolescence, and late adolescence periods. In the current study, separate scores were calculated for Social and Academic functioning at each age level, by averaging the sociability and withdrawal, peer relationships and social-sexual functioning items (Social domain) or the scholastic performance and adaptation to school items (Academic domain), which is the procedure used in prior studies (e.g., Allen et al., 2001, 2005). The PAS was completed according to standardized procedures by raters trained to reliably administer the instrument. A semi-structured interview was utilized with participants and their family members to gain information pertaining to the premorbid period (Cannon-Spoor et al., 1982). Family members were judged to be reliable informants in all cases on the basis of having substantial contact with the participant during childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. Collateral information was also obtained from hospital and academic records when available in order to complete PAS items more reliably. The extensive background information collected from patients, their family members, and academic and medical records was necessary to ensure that the information used to complete the PAS was accurate, since many of the cases included in the current study had been diagnosed with schizophrenia for many years prior to their evaluation at MPRC.

3. Results

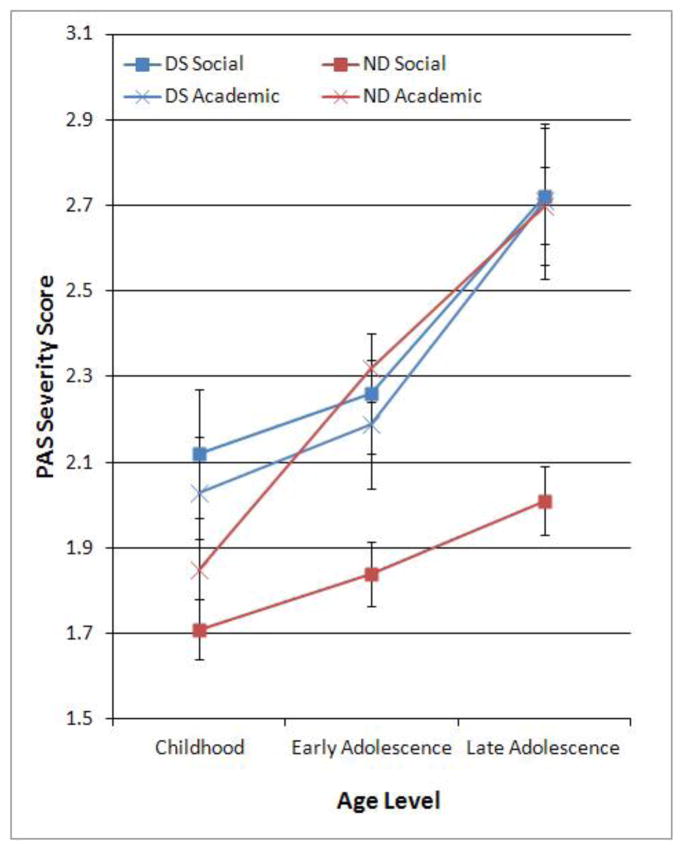

Means and standard errors for academic and social domains at each age period are presented for DS and ND patients in Figure 1. The overall mean scores of our patients are higher than those reported in the original Cannon-Spoor (1982) paper, but comparable to recent studies (e.g., Allen et al., 2005; Monte et al., 2008). A 2 Group (DS, ND) by 2 PAS Premorbid Domain (Social, Academic) by 3 PAS Age Levels (childhood, early adolescence, late adolescence) mixed model ANOVA was used to examine differences between DS and ND groups on premorbid deterioration of social and academic functioning from childhood to late adolescence. ANOVA indicated significant within subjects effects of PAS Age Level, F(2,342)=59.67, p<0.001, ηp2 =0.15 and PAS Premorbid Domain, F(1,342)=4.52, p< 0.04, ηp2=0.01. These significant effects indicate that in general, persons with schizophrenia show deterioration in premorbid functioning across both social and academic functioning from childhood to late adolescence, and have poorer premorbid academic than social function. The between-subjects effect of Group (DS vs. ND) was significant, F(1,342)=4.31, p=0.039, ηp2=0.01, indicating that DS show poorer global premorbid adjustment than ND. The PAS Age Level by Group interaction was nonsignificant, F(2,342)=1.94, p=0.14, suggesting that DS and ND have similar rates of global premorbid deterioration. The PAS Premorbid Domain by Group interaction was significant, F(1,342)=7.70, p=0.006, ηp2=0.02, as was the PAS Premorbid Domain by PAS Age Level interaction, F(2,342)=5.64, p=0.004, ηp2=0.02, and the three-way Group by Premorbid Domain by PAS Age Level interaction, F(2,342)=3.19, p=0.042. Follow-up ANOVAs were used to further investigate these interaction effects.

Figure 1.

Deterioration in Social and Academic Premorbid Adjustment Across Childhood, Early Adolescence, and Late Adolescence Periods in Deficit Syndrome (DS) and Non-Deficit syndrome (ND) groups.

Note. PAS = Premorbid Adjustment Scale. PAS Severity scores range from 0 (normal) to 6 (high impairment).

Mixed model ANOVA examining differences between the ND and DS groups on the PAS Social Domain across the three Age Levels indicated a significant effect for Group, F(1,342)=11.34, p<.001, ηp2=.03, and Age Level, F(2,342)=20.39, p<.0001, ηp2=0.06, as well as a significant Age Level by Group interaction, F(2,342)=3.71, p< 0.05, ηp2=0.008. Examination of Figure 1 indicates that the significant interaction was accounted for by poorer premorbid social functioning in the DS group compared to the ND group that began in childhood, with an accelerated decline from early adolescent to late adolescence. Comparable analyses for the Academic domain also indicated a significant effect for Age Level, F(2,343)=54.84, p<0.0001, ηp2=0.14, although the Group effect was not significant, F(1,343) = 0.008, p=0.93, ηp2=0.001, nor was the Age Level by Group interaction effect, F(2,343)=2.22, p=0.11, ηp2=0.006. These results suggest significant deterioration in academic premorbid functioning moving from childhood to late adolescence that was comparable for the DS and ND groups (see Figure 1).

Follow-up repeated measures ANOVAs were also used to examine interactions between age level and PAS Domain within each of the groups. For the DS group, there was a significant effect for Age Level, F(2,73)=23.11, p<0.0001, ηp2=0.24, but not for PAS Domain, F(1,73)= 0.14, p=0.71, ηp2=0.002, or for the Age Level by PAS Domain interaction effect, F(2,190)= 0.10, p= 0.91, ηp2=0.001. Thus, the DS group demonstrated comparable declines for social and academic domains from childhood through late adolescence. For the ND group, repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant effect for Age Level, F(2,270)=60.18, p<0.0001, ηp2= 0.18, and for PAS Domain, F(1,270)=27.76, p<0.0001, ηp2=0.09, as well as a significant Age Level by PAS Domain interaction effect, F(2,270)=21.54, p<0.0001, ηp2=0.07. As can be seen from Figure 1, this interaction effect was accounted for by a steeper decline in premobid academic adjustment compared to social adjustment across the age levels.

4. Discussion

The most prominent finding from the current study was that the DS group had significantly poorer social premorbid functioning than the ND group. This difference was present during childhood and there was an accelerated decline between early and late adolescence. Because these differences were present as early as childhood, low social drive may be a very early indicator of the neurodevelopmental abnormalities that later go on to be expressed as a schizophrenia phenotype characterized by primary and enduring negative symptoms. Although the PAS does encompass the entirety of childhood prior to age 11, the measure is not specific enough to allow for an estimation of premorbid function in very early ages. It would be interesting to use the home video method developed by Walker et al. (1994) to determine whether these social abnormalities are present as early as infancy and toddlerhood to a greater extent in individuals who are later categorized as DS. The fact that social functioning was found to deteriorate significantly more rapidly from early adolescence to late adolescence in DS compared to ND participants suggests that accelerated premorbid decline in social functioning may be a unique marker for patients who later go on to develop DS. Patients with predominant negative symptoms, including those with the DS subtype are unlikely to fully recover throughout the course of illness (Strauss et al., 2010), and negative symptoms do not respond well to currently available pharmacological treatments (Breier et al., 1994; Buchanan et al., 1998). In this way, sharp decline in social functioning prior to the onset of schizophrenia may provide an important prognostic indicator that could be useful in treatment planning and rehabilitation.

These findings also clarify results of previous studies, which found poorer general premorbid functioning in DS (Kirkpatrick et al., 1996; Buchanan et al., 1990; Fenton & McGlashan, 1994; Galderisi et al., 2002), by demonstrating that poorer premorbid function is specific to the social aspects of functioning, but not academic functioning where the DS and ND groups did not differ. With regard to this latter point, the dissociation between academic and social premorbid deterioration reported in other studies that did not consider the influence of negative symptoms on premorbid abnormalities (e.g., Allen et al., 2005) was not observed in the DS cases. As is clear from Figure 1, while the ND group in the current study demonstrated significant discrepancies between social and academic function, with academic functioning being more impaired during childhood, and demonstrating a sharper rate of decline from childhood to late adolescence, this pattern was not present in DS patients. Rather, there were no significant differences between social and academic functioning for the DS patients at any age level. Furthermore, this absence of difference was primarily accounted for by increased social impairment at all age levels in the DS group, such that the DS group’s social impairment was comparable to ND group’s academic impairment, and more severe than the ND group’s social impairment. Increased academic relative to social deterioration present in the ND group is generally consistent with results of Allen et al. (2005) who found that a group of male veterans declined steeply in academic but not social premorbid adjustment, particularly from early to late adolescence, a finding that was later replicated (Monte et al., 2008). Those studies suggest that premorbid academic functioning is particularly susceptible to deterioration during late adolescence in schizophrenia, and that deterioration in premorbid academic functioning from early to late adolescence may be a unique premorbid marker for schizophrenia (Allen et al., 2005; Fuller et al., 2002; Gunnell et al., 2002; Jones et al., 1994; Monte et al., 2008; van Oel et al., 2002). The current findings clarify the results of these earlier studies by indicating that decline in premorbid academic function may be relatively common in the majority of persons with schizophrenia, but is not a prominent distinguishing feature of individuals who later go on to develop primary and enduring negative symptoms.

The current study had a number of limitations, including the use of retrospective interviews and chart reviews to established premorbid functioning. This limitation is mitigated to some extent by the consistency of the current findings with those reported in studies using other methods to ascertain premorbid functioning. Nonetheless, the PAS can be difficult to rate when individuals are older at the time of interview, as well as when they have negative symptoms, and future studies would benefit from examining the generalizability of these findings using alternative measures of premorbid functioning.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source

This project was supported by NIMH grant 5P30MH068580-04. Study sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation; the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

We would like to thank staff at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center for their role in the completion of this research.

Footnotes

Comparisons between the schizoaffective and schizophrenia participants in the ND group indicated no significant differences on age, F(1,344)=1.89, p=.0.17, education, F(1,344)=0.48, p=0.49, gender, chi square (1)=2.23, p=0.13, or race, chi square (4)=4.06, p=0.40. Also, ANOVAs indicated there were no differences between these groups for the positive symptoms of Hallucination, Delusions, Bizarre Behavior, and Thought Disorder as assessed with the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (F = 2.15, p = 0.14, or for negative symptoms of Restricted Affect, Diminished Emotion, Poverty of Speech, Curbed Interests, Sense of Purpose, and Social Drive as assessed by the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome (SDS), F’s <2.39, p > 0.12. Thus, the schizophrenia and schizoaffective participants were combined for the current study.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Dr.’s Strauss and Miski performed statistical analyses and data processing steps. Data collection was performed by research assistants at the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. Drs. Kirkpatrick and Buchanan conducted symptom interviews on many of the subjects. Dr.’s Strauss and Allen wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Subsequent drafts of the manuscript were edited by all authors, who have contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen DN, Frantom LV, Strauss GP, van Kammen DP. Differential patterns of premorbid academic and social deterioration in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2005;75:389–397. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen DN, Kelley ME, Miyatake RK, Gurklis JA, Jr, van Kammen DP. Confirmation of a two-factor model of premorbid adjustment in males with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:39–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive symptoms (SAPS) University of Iowa; Iowa City: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Breier A, Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Davis OR, Irish D, Summerfelt A, Carpenter WT., Jr Effects of clozapine on positive and negative symptoms in outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:20–26. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson G, Whelahan HA, Bell M. Memory and executive function impairments in deficit syndrome schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2001;102:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00245-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Breier A, Kirkpatrick B, Ball P, Carpenter WT., Jr Positive and negative symptom response to clozapine in schizophrenic patients with and without the deficit syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:751–760. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Strauss ME, Kirkpatrick B, Holstein C, Breier A, Carpenter WT., Jr Neuropsychological impairments in deficit vs nondeficit forms of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:804–811. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950100052005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan RW, Kirkpatrick B, Heinrichs DW, Carpenter WT., Jr Clinical correlates of the deficit syndrome of schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:290–294. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.3.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Jones P, Gilvarry C, Rifkin L, McKenzie K, Foerster A, Murray RM. Premorbid social functioning in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: similarities and differences. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1544–1550. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1982;8:470–484. doi: 10.1093/schbul/8.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter WT, Jr, Heinrichs DW, Wagman AM. Deficit and nondeficit forms of schizophrenia: the concept. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145(5):578–583. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J, Kaplan Z, Knobler H, Davidson-Sagi N, Davidson M. Cognitive performance in schizophrenia patients assessed before and following the first psychotic episode. Schizophr Res. 2003;65(2–3):87–94. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(03)00056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Saperstein AM, Gold JM, Kirkpatrick B, Carpenter WT, Jr, Buchanan RW. Neuropsychology of the deficit syndrome: new data and meta-analysis of findings to date. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:1201–1212. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Brown LA, Minor KS. The psychiatric symptomatology of deficit schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1–3):122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenton WS, McGlashan TH. Antecedents, symptom progression, and long-term outcome of the deficit syndrome in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(3):351–356. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller R, Nopoulos P, Arndt S, O’Leary D, Ho B, Andreasen NC. Longitudinal assessment of premorbid cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia through examination of standardized scholastic test performance. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1183–1189. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galderisi S, Maj M, Mucci A, et al. Historical, psychopathological, neurological and neuropsychological aspects of deficit schizophrenia: a multicenter study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:983–990. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell D, Harrison G, Rasmussen F, Fouskakis D, Tynelius P. Associations between premorbid intellectual performance, early-life exposures and early-onset schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181:298–305. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.4.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Rodgers B, Murray R, Marmot M. Childhood developmental risk factors for adult schizophrenia in the British 1946 birth cohort. Lancet. 1994;344:1398–1402. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90569-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, McKenney PD, Alphs LD, Carpenter WT., Jr The schedule for the deficit syndrome: an instrument for research in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 1989;30:119–123. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Buchanan RW, Ross DE, Carpenter WT., Jr A separate disease within the syndrome of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:165–171. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Galderisi S. Deficit schizophrenia: an update. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:143–147. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Ram R, Bromet E. The deficit syndrome in the Suffolk County Mental Health Project. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:119–126. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Amador XF, Flaum M, Yale SA, Gorman JM, Carpenter WT, Tohen M, McGlashan T. The deficit syndrome in the DSM-IV Field Trial, I: alcohol and other drug abuse. Schizophr Res. 1996;20:69–77. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(95)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus J, Hans SL, Auerbach JG, Auerbach AG. Children at risk for schizophrenia: the Jerusalem Infant Development study: II. Neurobehavioral deficits at school age. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:797–809. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820220053006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monte RC, Goulding SM, Compton MT. Premorbid functioning of patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis: a comparison of deterioration in academic and social performance, and clinical correlates of Premorbid Adjustment Scale scores. Schizophr Res. 2008;104(1–3):206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Reddy R, Schnur DB. A developmental model of negative syndromes in schizophrenia. In: Greden J, Tandon R, editors. Negative schizophrenic symptoms: pathophysiology and clinical implications. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Murray RM, O’Callaghan E, Castle DJ, Lewis SW. A neurodevelopmental approach to the classification of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1992;18(2):319–332. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.2.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenberg A, Weiser M, Rabinowitz J, Caspi A, Schmeidler J, Mark M, Kaplan Z, Davidson M. A population based cohort study of premorbid intellectual, language, and behavioral functioning in patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, and nonpsychotic bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:2027–2035. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.12.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso IM, Bearden CE, Hollister JM, Gasperoni TL, Sanchez LE, Hadley T, Cannon TD. Childhood neuromotor dysfunction in schizophrenia patients and their unaffected siblings: a prospective cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:367–378. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman J, Walker E, Ekstrom M, Schulsinger F, Sorensen H, Mednick S. Childhood videotaped social and neuromotor precursors of schizophrenia: a prospective investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):2021–2027. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffman J, Sorensen HJ, Maeda J, Mortensen EL, Victoroff J, Hayashi K, et al. Childhood motor coordination and adult schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):1041–1047. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Harrow M, Grossman LS, Rosen C. Periods of Recovery in Deficit Syndrome Schizophrenia: A 20-Year Multifollowup Longitudinal Study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2010;36:788–799. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss GP, Jetha SS, Duke LA, Ross SA, Allen DN. Impaired Facial Affect Labeling and Discrimination in Patients with Deficit Syndrome Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research. 2010;118:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Kammen DP, Kelley ME, Gilbertson MW, Gurklis JA, O’Connor DT. CSF dopamine b-hydroxylase in schizophrenia: associations with premorbid functioning and brain computerized tomography scan measures. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:372–378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.3.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Oel CJ, Sitskoorn MM, Cremer MP, Kahn RS. School performance as a premorbid marker for schizophrenia: a twin study. Schizophr Bull. 2002;28:401–414. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF. Developmentally moderated expressions of the neuropathology underlying schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1994;20:453–478. doi: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker EF, Lewine RR, Neumann C. Childhood behavioral characteristics and adult brain morphology in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1996;22:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(96)00070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yao S, Kirkpatrick B, Shi C, Yi J. Psychopathology and neuropsychological impairments in deficit and nondeficit schizophrenia of Chinese origin. Psychiatry Res. 2008;158:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberger DR. Schizophrenia as a neurodevelopment disorder. In: Hirsch SR, Weinberger DR, editors. Schizophrenia. Blackwell Science; Cambridge, MA: 1995. [Google Scholar]