Abstract

Objective

Supported employment is the evidence-based treatment of choice for assisting individuals with severe mental illness to achieve competitive employment, but few supported employment programs specifically target older clients with psychiatric illness. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of supported employment for middle-aged or older people with schizophrenia.

Method

Participants included 58 outpatients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder aged 45 or older who were recruited from a community mental health clinic. Participants were randomly assigned to receive Individual Placement and Support (IPS; the manualized version of supported employment) or conventional vocational rehabilitation (CVR) for one year, and completed assessments at baseline, six months, and twelve months.

Results

IPS was superior to CVR on nearly all work outcome measures, including attainment of competitive employment, weeks worked, and wages earned. Fifty-seven percent of IPS participants worked competitively, compared with 29% of CVR participants; 70% of IPS participants obtained any paid work, compared with 36% of CVR participants. Within the IPS group, better baseline functional capacity (as measured by the UCSD Performance Based Skills Assessment) and more recent employment were modestly associated with better work outcomes.

Conclusions

Middle-aged and older adults with schizophrenia are good candidates for supported employment services.

Keywords: psychosis, rehabilitation, geriatric psychiatry

1. Introduction

Unemployment is common in schizophrenia (Marwaha and Johnson, 2004) and contributes most to its economic cost (Wu et al., 2002). However, supported employment (SE) is a widely accepted evidence-based practice focused on competitive work attainment (Dixon et al., 2010). Rates of competitive work in SE are 51–70%, compared with 18–24% in conventional vocational rehabilitation (effect sizes .79–.96; Bond et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2011; Twamley et al., 2003).

The number of middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia is growing quickly (Palmer et al., 1999), but services have not kept pace. Age does not predict work status in this population or work outcomes in SE programs (Bond and Drake, 2008; Dixon et al., 2010; Bell et al., 2005), but few SE programs specifically target older clients. Many older consumers want to work (Auslander and Jeste, 2002), but the average age of study participants is only 38 (Bond et al., 2008), leaving most service-users under-studied and underserved. Older consumers may have less severe psychiatric symptoms, less substance abuse, and more work experience (Folsom et al., 2009; Jeste et al., 2003; Patterson and Jeste, 1999), but they also face barriers including ageism, longer absences from the workforce, and age-related cognitive decline.

We report the results of the first randomized controlled trial of SE for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia. Individuals aged 45 or older were included, given the 20% shorter lifespan and earlier onset of “middle-age” in schizophrenia (Kirkpatrick et al., 2008). When compared with conventional vocational rehabilitation (CVR), we hypothesized that Individual Placement and Support (IPS; the manualized version of SE; Becker and Drake, 2003) would produce higher levels of job attainment, weeks worked, dollars earned, and faster job placement.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (see Table 1) included fifty-eight outpatients with schizophrenia (n=23) or schizoaffective disorder (n=35) from a community mental health clinic, all aged 45 or older, unemployed, and stating a goal of working. Participants were excluded for substance abuse/dependence within 30 days, history of head injury with loss of consciousness over 30 minutes, mental retardation, or neurological disorders. Most participants were middle-aged (mean=51; oldest=60) and had a “poor vocational outcome” (79% without significant paid work in two years; Bellack et al., 1999), but 86% had once worked at least 12 months continuously. After complete description of the study to the subjects, written informed consent was obtained. The study was approved by the IRB and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Fifty participants were included in a preliminary report focusing on job acquisition rate (Twamley et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| CVR (n=30) | IPS (n=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | t* or χ2 | df* | p | |

| Demographic variables | |||||

| Age, years | 51.75 (5.08) | 50.30 (3.47) | −1.26 | 47.24 | .214 |

| Education, years | 12.43 (2.71) | 12.43 (2.40) | 0.01 | 54.03 | .994 |

| Gender, % male | 53.6 | 73.3 | 2.45 | 1.00 | .118 |

| Ethnicity, % Caucasian | 57.1 | 63.3 | 0.23 | 1.00 | .630 |

| Illness-related variables | |||||

| Diagnosis, % schizoaffective | 67.9 | 53.3 | 1.28 | 1.00 | .259 |

| Antipsychotic Type | 4.37 | 3.00 | .224 | ||

| None | 10.7 | 13.3 | |||

| Atypical | 78.6 | 66.7 | |||

| Typical | 10.7 | 6.7 | |||

| Typical and atypical | 0.0 | 13.3 | |||

| Daily antipsychotic dose, CPZE | 258.46 (255.49) | 390.49 (444.71) | 1.34 | 41.48 | .188 |

| Duration of illness, years | 23.43 (11.52) | 24.97 (10.05) | 0.54 | 53.75 | .591 |

| PANSS - Positive Total | 14.91 (6.24) | 15.86 (4.13) | 0.62 | 36.78 | .537 |

| PANSS - Negative Total | 17.00 (5.85) | 15.21 (5.41) | −1.12 | 45.50 | .268 |

| HAM-D 17 - Total Score | 11.27 (7.77) | 10.11 (6.52) | −0.56 | 40.92 | .575 |

| Alcohol/substance abuse during study, % | 18.2 | 25.9 | 0.42 | 1.00 | .518 |

| Work experience variables | |||||

| Monthly entitlement income, dollars | 828.90 (312.24) | 830.91 (285.14) | 0.64 | 53.71 | .525 |

| Time since last job, years | 7.67 (6.83) | 6.02 (7.29) | −0.88 | 54.90 | .381 |

| Percent of lifetime working | 55.25 (27.68) | 50.81 (29.22) | −0.58 | 52.83 | .565 |

| UPSA - Total Score | 84.12 (9.52) | 83.76 (10. 12) | −0.13 | 44.78 | .901 |

Note.

t and df for unequal variances used. CPZE = chlorpromazine equivalent; CVR = Conventional Vocational Rehabilitation; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IPS = Individual Placement and Support; IQ = Intelligence Quotient; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; UPSA = UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment

Twelve participants (IPS=7; CVR=5) dropped out (see CONSORT diagram in Supplemental Data; no significant difference between groups, χ2=0.27, p=0.607). Dropouts were less likely than study completers to be taking atypical antipsychotics (41.7% vs. 80.4%; χ2=10.57, p=0.014), more likely to have a diagnosis of schizophrenia (66.7% vs. 33.3%, χ2=4.61, p=0.032), and had a more remote work history (13 vs. 5 years since last job; t=2.44, df=11.89, p=0.032).

2.2. Procedure

Referrals were made by clinicians and diagnoses were confirmed with DSM-IV criteria-based chart reviews. Participants were randomized to IPS (n=30) or CVR (n=28) for one year, with assessments administered at baseline, 6 months, and 12 months, and work outcome data collected weekly.

IPS

IPS participants received manualized SE (Becker and Drake, 2003) from an employment specialist whose maximum caseload was 25. IPS emphasizes competitive work, integrated mental health and SE services, any client can participate, rapid job searching, service-users’ preferences, time-unlimited follow-along support, benefits counseling, and providing services in community settings. IPS fidelity ratings (Bond et al., 1997), by DRB, improved from “fair” to “good” over the study. “High” fidelity could not be achieved due to study design (only schizophrenia/schizoaffective clients included; study duration was one year; only one employment specialist).

CVR

Participants randomized to CVR were referred to the Department of Rehabilitation for orientation, intake, and eligibility determination, then became clients of a brokered program for individuals with mental illness. Vocational counselors carried caseloads of 35 clients; additional staff provided job-readiness and prevocational coaching/classes. To promote engagement and reduce attrition, study staff assisted CVR participants with appointment-setting, reminder calls, and transportation, if needed, to the first three appointments.

2.3. Measures

The UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment (UPSA; Patterson et al., 2001) measured functional capacity in five domains (Household Chores, Communication, Finance, Transportation and Planning Recreational Activities). Psychiatric symptom severity measures included the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987) and Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D; Hamilton, 1960). Raters were blinded and reliable (ICCs>.80).

Hours worked and wages earned (verified with pay-stubs) were collected weekly via self-report. Competitive work was defined as employment paying at least minimum wage and not reserved for the disabled; other paid employment included set-aside jobs and work paying below minimum wage.

2.4. Analyses

All analyses were intent-to-treat. Dropouts were assumed not to work (Mueser et al., 2004); zeros were imputed for employment data following dropout. Wages earned and weeks worked were not normally distributed due to zero values, necessitating nonparametric tests (Delucchi and Bostrom, 2004).

Demographic characteristics and time to first job were compared between groups using t-tests and χ2 analyses. Work attainment was examined using χ2 analyses, area under the curve (AUC), and number needed to treat (NNT; Kraemer and Kupfer, 2006). Weeks worked and wages earned were examined with Mann-Whitney nonparametric tests. Pearson and Spearman correlations were used to examine relationships between work outcomes and various predictors within each group.

3. Results

The IPS and CVR groups did not differ on any demographic characteristics (all ps>0.12; see Table 1).

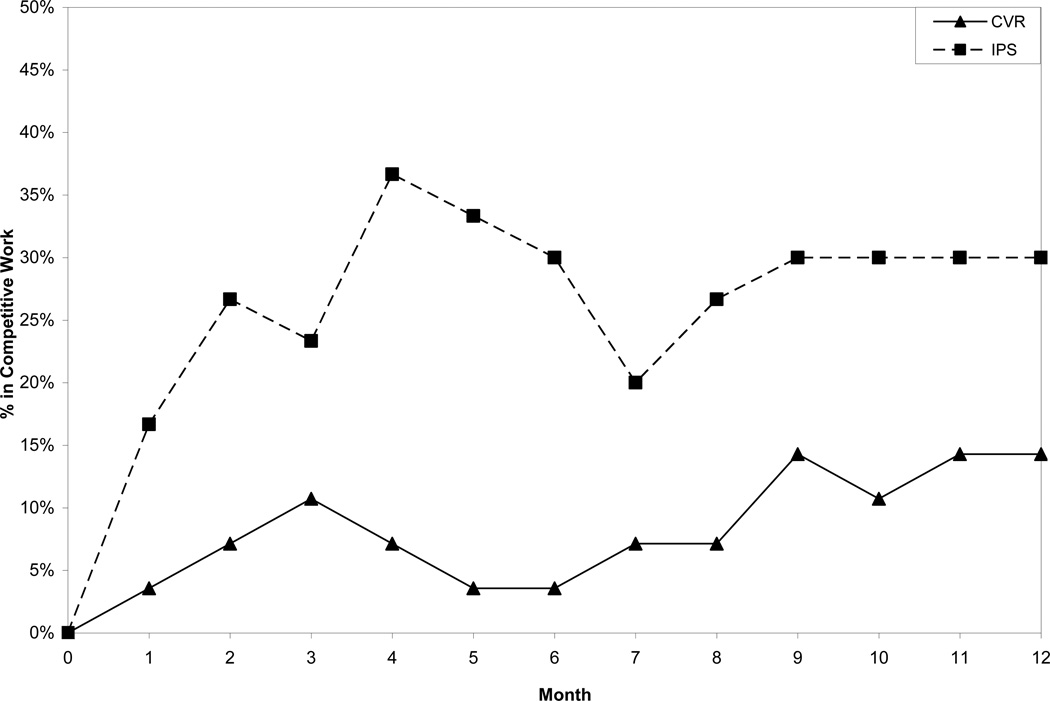

IPS was superior to CVR on most outcome measures (see Table 2). Fifty-seven percent of IPS participants worked competitively, compared with 29% of CVR participants; 70% of IPS participants obtained any paid work, compared with 36% of CVR participants. Rates of competitive employment over time are shown in Figure 1. The AUC for competitive work was 0.64, indicating that IPS yielded better work outcomes than did CVR. The NNT for competitive work (3.56) indicated that providing IPS to about three people would result in one more competitive job than would CVR. AUCs and NNTs were similar for any paid work (0.67 and 2.92, respectively). Table 3 shows jobs obtained. The IPS group had greater median values for weeks worked and wages earned. Those receiving IPS obtained their first competitive job non-significantly faster (94 days) than did those receiving CVR (138 days).

Table 2.

Work outcomes in IPS and CVR

| IPS (n=30) | CVR (n=28) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | χ2 | df | p | |

| Obtained competitive work, % | 56.7 | 28.6 | 4.66 | 1.00 | .031 |

| Obtained any paid work, % | 70.0 | 35.7 | 6.84 | 1.00 | .009 |

| Median | Median | MW Z-Score | p | ||

| Weeks of competitive work | 4.50 | 0.00 | −2.34 | .019 | |

| (mean=10.50, SD=13.50) | (mean=3.61, SD=7.80) | ||||

| Wages from competitive work | $644.17 | $0.00 | −2.21 | .027 | |

| (mean=$1857, SD=$2969) | (mean=$456, SD=$883) | ||||

| Weeks of any paid work | 5.50 | 0.00 | −2.49 | .013 | |

| (mean=12.07, SD=14.18) | (mean=4.92, SD=9.19) | ||||

| Wages from any paid work | $730.00 | $0.00 | −2.58 | .010 | |

| (mean=$2047, SD=$3018) | (mean=$607, SD=$1174) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | t | df | p | |

| Time to competitive work, days | 94.06 (87.99) | 138.00(108.10) | −1.08 | 11.55 | .336 |

Note. Means and SDs for weeks worked and wages earned are provided, but medians were used for inferential statistics due to skewed distributions. CVR = Conventional Vocational Rehabilitation; IPS = Individual Placement and Support; MW = Mann-Whitney

Figure 1.

Percent of CVR and IPS Participants Working Competitively By Month in Study

Table 3.

Types of employment in IPS and CVR

| IPS | CVR | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Jobs | Competitive Jobs | ||||||||||

| Amusement Park Worker | House Repairer | ||||||||||

| Baler | Kitchen Helper | ||||||||||

| Bell Ringer | Maintenance Repairer | ||||||||||

| Boat Loader | Office Furniture Mover | ||||||||||

| Carpenter | Receptionist | ||||||||||

| Cashier | Sandwich-Board Carrier | ||||||||||

| Certified Nursing Assistant | Stock Clerk | ||||||||||

| Collection Clerk | Telephone Solicitor | ||||||||||

| Dishwasher | |||||||||||

| Food Service Driver | |||||||||||

| Landscape Laborer | |||||||||||

| Mail Handler | |||||||||||

| Maintenance Repairer | |||||||||||

| Membership Solicitor | |||||||||||

| Merchandise Deliverer | |||||||||||

| Parking Lot Attendant | |||||||||||

| Personal Attendant | |||||||||||

| Receptionist | |||||||||||

| Service Station Attendant | |||||||||||

| Social Services Aide | |||||||||||

| Stock Clerk | |||||||||||

| Telephone Solicitor | |||||||||||

| Usher | |||||||||||

| Other Paid Jobs | Other Paid Jobs | ||||||||||

| Advertising Material Distributor | Animal Caretaker | ||||||||||

| Auto Body Repairer | Health Companion | ||||||||||

| Cook Helper | House Repairer | ||||||||||

| Dining Room Attendant | Photocopy Machine Operator | ||||||||||

| Dishwasher | Sales Driver Helper | ||||||||||

| Election Clerk | Social Services Aide | ||||||||||

| Janitor | Teacher Aide | ||||||||||

In exploratory analyses, we examined the bivariate relationships between competitive work outcomes and demographic characteristics, illness-related variables, previous work experience, and UPSA performance (see Tables 4 and 5). In IPS, the longer clients had been unemployed, the less likely they were to work, the fewer weeks they worked, and the less money they earned; higher levels of baseline functional capacity were associated with higher rates of competitive work. In CVR, more severe depressive symptoms were associated with worse work outcomes.

Table 4.

Bivariate correlations between predictor variables and competitive work outcomes in the IPS group (n=30)

| Attainment of competitive work |

Weeks of competitive work |

Wages from competitive work |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | r | p | n | ρ | p | n | ρ | p | |

| Demographic variables | |||||||||

| Age, years | 30 | −.16 | .399 | 30 | −.27 | .147 | 30 | −.23 | .214 |

| Education, years | 30 | .07 | .694 | 30 | .08 | .661 | 30 | .08 | .673 |

| Gender (male/female) | 30 | −.22 | .236 | 30 | −.13 | .503 | 30 | −.07 | .703 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian/minority) | 30 | −.31 | .094 | 30 | −.22 | .241 | 30 | −.21 | .259 |

| Illness-related variables | |||||||||

| Diagnosis (schizoaffective/schizophrenia) | 30 | .13 | .508 | 30 | .17 | .371 | 30 | .14 | .471 |

| Daily antipsychotic dose, CPZE | 27 | −.04 | .861 | 27 | −.33 | .095 | 27 | −.31 | .115 |

| Duration of illness, years | 30 | −.03 | .874 | 30 | −.04 | .845 | 30 | −.08 | .658 |

| PANSS - Positive Total | 28 | −.17 | .376 | 28 | −.21 | .280 | 28 | −.21 | .282 |

| PANSS - Negative Total | 28 | −.14 | .488 | 28 | −.05 | .804 | 28 | −.01 | .962 |

| HAM-D 17-Total | 28 | .01 | .946 | 28 | .08 | .676 | 28 | .02 | .901 |

| Alcohol/substance abuse during study (yes/no) | 27 | .19 | .345 | 27 | .14 | .498 | 27 | .15 | .462 |

| Work experience variables | |||||||||

| Monthly entitlement income, dollars | 30 | −.24 | .209 | 30 | −.08 | .688 | 30 | −.08 | .677 |

| Time since last job, years | 30 | −.40 | .030 | 30 | −.36 | .048 | 30 | −.43 | .017 |

| Percent of adult lifetime working | 29 | .34 | .072 | 29 | .32 | .090 | 29 | .32 | .088 |

| Cognitive/Functional variables | |||||||||

| Premorbid IQ estimate | 28 | −.24 | .226 | 28 | −.16 | .409 | 28 | −.15 | .445 |

| Attention z-score | 29 | −.12 | .535 | 29 | −.10 | .597 | 29 | −.06 | .771 |

| Processing Speed z-score | 29 | .00 | .988 | 29 | .03 | .881 | 29 | .10 | .591 |

| Working Memory z-score | 29 | −.11 | .570 | 29 | −.22 | .251 | 29 | −.18 | .344 |

| Language z-score | 29 | .04 | .839 | 29 | −.13 | .507 | 29 | −.04 | .831 |

| Learning z-score | 29 | .17 | .374 | 29 | .12 | .532 | 29 | .14 | .468 |

| Memory z-score | 29 | .20 | .295 | 29 | .29 | .120 | 29 | .30 | .119 |

| Executive Functioning z-score | 29 | −.04 | .841 | 29 | −.07 | .729 | 29 | −.02 | .901 |

| Global Neuropsychological z-score | 29 | −.02 | .913 | 29 | −.06 | .767 | 29 | .00 | .986 |

| UPSA - Total Score | 25 | .41 | .041 | 25 | .37 | .072 | 25 | .32 | .115 |

Note. Bold font indicates a statistically significant correlation; CPZE = chlorpromazine equivalent; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IPS = Individual Placement and Support; IQ = Intelligence Quotient; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; UPSA = UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment

Table 5.

Bivariate correlations between predictor variables and competitive work outcomes in the CVR group (n=28)

| Attainment of competitive work |

Weeks of competitive work |

Wages from competitive work |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | r | p | n | ρ | p | n | ρ | p | |

| Demographic variables | |||||||||

| Age, years | 28 | .11 | .574 | 28 | .13 | .519 | 28 | .16 | .416 |

| Education, years | 28 | .19 | .320 | 28 | .09 | .662 | 28 | .09 | .654 |

| Gender (male/female) | 28 | .27 | .162 | 28 | .32 | .094 | 28 | .32 | .094 |

| Ethnicity (Caucasian/minority) | 28 | −.23 | .243 | 28 | −.29 | .133 | 28 | −.27 | .167 |

| Illness-related variables | |||||||||

| Diagnosis (schizoaffective/schizophrenia) | 28 | −.24 | .215 | 28 | −.25 | .201 | 28 | −.21 | .275 |

| Daily antipsychotic dose, CPZE | 27 | .15 | .459 | 27 | .16 | .412 | 27 | .12 | .554 |

| Duration of illness, years | 28 | −.01 | .960 | 28 | .03 | .873 | 28 | .00 | 1.000 |

| PANSS - Positive Total | 23 | −.10 | .664 | 23 | −.07 | .753 | 23 | −.09 | .667 |

| PANSS - Negative Total | 23 | −.27 | .206 | 23 | −.33 | .124 | 23 | −.25 | .256 |

| HAM-D 17-Total | 22 | −.50 | .018 | 22 | −.73 | .000 | 22 | −.70 | .000 |

| Alcohol/substance abuse during study (yes/no) | 22 | .03 | .910 | 22 | .05 | .823 | 22 | .05 | .823 |

| Work Experience variables | |||||||||

| Monthly entitlement income, dollars | 26 | .21 | .297 | 26 | .15 | .458 | 26 | .15 | .471 |

| Time since last job, years | 27 | −.27 | .173 | 27 | −.20 | .317 | 27 | −.21 | .302 |

| Percent of adult lifetime working | 26 | .17 | .411 | 26 | .08 | .689 | 26 | .11 | .610 |

| Cognitive/Functional variables | |||||||||

| Premorbid IQ estimate | 22 | −.13 | .576 | 22 | −.01 | .972 | 22 | .00 | .995 |

| Attention z-score | 24 | .03 | .892 | 24 | .11 | .615 | 24 | .14 | .519 |

| Processing Speed z-score | 24 | −.04 | .856 | 24 | .06 | .797 | 24 | .00 | .998 |

| Working Memory z-score | 24 | .23 | .289 | 24 | .17 | .418 | 24 | .17 | .436 |

| Language z-score | 24 | .13 | .555 | 24 | .13 | .533 | 24 | .11 | .620 |

| Learning z-score | 24 | −.07 | .729 | 24 | −.05 | .812 | 24 | .02 | .944 |

| Memory z-score | 24 | −.05 | .819 | 24 | −.03 | .895 | 24 | −.02 | .937 |

| Executive Functioning z-score | 24 | .10 | .655 | 24 | .05 | .803 | 24 | .04 | .855 |

| Global Neuropsychological z-score | 24 | .04 | .846 | 24 | .06 | .795 | 24 | .06 | .780 |

| UPSA - Total Score | 22 | .10 | .665 | 22 | .04 | .854 | 22 | .06 | .793 |

Note. Bold font indicates a statistically significant correlation; CPZE = chlorpromazine equivalent; CVR = Conventional Vocational Rehabilitation; HAM-D = Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; IQ = Intelligence Quotient; PANSS = Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; UPSA = UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment

4. Discussion

Our results suggest that middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia can benefit from SE: 57% of our sample obtained competitive work, and 70% obtained any paid work. The rate of competitive employment in our IPS group was similar to benchmarks from meta-analyses (51–70%; Bond et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2011; Twamley et al., 2003) and consistent with retrospective analyses demonstrating that older clients can benefit from SE (Bell et al., 2005; Campbell et al., 2011).

Similar to Campbell et al. (2010), we found that people with more recent work histories had better work outcomes, possibly reflecting better work skills and functioning, or better chances of getting hired with more recent job experience. Better baseline functional capacity was also associated with obtaining competitive work, supporting the UPSA as a predictor not only of current functional status (Mausbach et al., 2008), but also of future functioning.

Consistent with previous work (Bond and Drake, 2008), most demographic and illness characteristics did not predict work outcomes. In CVR, depressive symptoms adversely affected work outcomes, perhaps due to lack of integration between CVR and psychiatric treatment. Unlike some previous work (Campbell et al., 2010), we found that entitlement benefits did not affect work outcomes, although we examined benefit amount, not mere presence of benefits.

Our study has several limitations. Our sample size was small and some of our analyses may have been underpowered. IPS was delivered by a single employment specialist. We considered dropouts not to have worked, although some dropouts may have worked on their own. We did not correct for alpha inflation, and our results should be considered preliminary until they are replicated. Longer studies will be needed to examine the long-term outcomes of SE.

We conclude that middle-aged and older patients with schizophrenia can benefit from SE and should be recruited into SE programs. Although recency of past work and functional capacity were associated with SE outcomes in our sample, the associations were moderate, suggesting that even individuals with remote histories of work or poor functional skills can be successful. Augmenting SE with additional psychosocial treatment (Kern et al., 1999) aimed at reducing individual barriers to work (Campbell et al., 2011) may improve work outcomes and functional recovery more broadly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Amanda Lewis, Nicole Loebach, and Jenille Narvaez to this study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Contributors

Elizabeth W. Twamley and Dilip V. Jeste designed the study. Elizabeth W. Twamley, Lea Vella, and Cynthia Z. Burton conducted the statistical analyses. Elizabeth W. Twamley wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all co-authors edited and revised the manuscript. Morris D. Bell and Deborah R. Becker assisted with interpretation of data analyses. Deborah R. Becker additionally provided guidance on supported employment implementation and fidelity ratings. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Auslander LA, Jeste DV. Perception of problems and needs for service among older outpatients with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders. Community Ment. Health J. 2002;38:391–340. doi: 10.1023/a:1019808412017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker DR, Drake RE. A Working Life for People with Severe Mental Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Fiszdon JM, Greig TC, Bryson GJ. Can older people with schizophrenia benefit from work rehabilitation? J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2005;193:293–301. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000161688.47164.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell MD, Zito W, Greig T, Wexler BE. Neurocognitive enhancement therapy with vocational services: work outcomes at two-year follow-up. Schizophr. Res. 2008;105:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellack AS, Gold JM, Buchanan RW. Cognitive rehabilitation for schizophrenia: problems, prospects, and strategies. Schizophr. Bull. 1999;25:257–274. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB. Brief Visual-Spatial Memory Test – revised Professional Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Florida: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benedict RHB, Schretlen D, Groninger L, Brandt J. Hopkins Verbal Learning Test - revised: Normative data and analysis of inter-form and test-retest reliability. Clin. Neuropsychol. 1998;12:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Benton AL, Hamsher KS. Multilingual aphasia examination. AJA Associated; Iowa: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Becker DR, Drake RE, Vogler KM. A fidelity scale for the individual placement and support model of supported employment. Rehabil. Couns. Bull. 1997;40:265–284. [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE. Predictors of competitive employment among patients with schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry. 2008;21:362–369. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328300eb0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2008;31:280–290. doi: 10.2975/31.4.2008.280.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Bond GR, Drake RE. Who benefits from supported employment: A meta-analytic study. Schizophr. Bull. 2011;37:370–380. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Bond GR, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Xie H. Client predictors of employment outcomes in high-fidelity supported employment: a regression analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2010;198:556–563. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181ea1e53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornblatt BA, Lenzenweger MF, Erlenmeyer-Kimling L. The continuous performance test, identical pairs version: II. Contrasting attentional profiles in schizophrenic and depressed patients. Psychiatry. Res. 1989;29:65–85. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90188-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Bostrom A. Methods for analysis of skewed data distributions in psychiatric clinical studies: working with many zero values. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:1159–1168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon LB, Dickerson F, Bellack AS, Bennett M, Dickinson D, Goldberg RW, Lehman A, Tenhula WN, Calmes C, Pasillas RM, Peer J, Kreyenbuhl J. Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT): The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychosocial treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr. Bull. 2010;36:48–70. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom DP, Depp C, Palmer BW, Mausbach BT, Golshan S, Fellows I, Cardenas V, Patterson TL, Kraemer HC, Jeste DV. Physical and mental health-related quality of life among older people with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2009;108:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JM, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, Dixon LB, Lehman AF. Cognitive correlates of job tenure among patients with severe mental illness. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2002;159:1395–1402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ. Stroop Color and Word Test. Stoelting Company; Illinois: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Grober E, Sliwinski M. Development and validation of a model for estimating premorbid verbal intelligence in the elderly. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 1991;13:933–949. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeste DV, Twamley EW, Eyler Zorrilla LT, Golshan S, Patterson TL, Palmer BW. Aging and outcome in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2003;107:336–343. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.01434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 1987;13:261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern RS, Glynn SM, Horan WP, Marder SR. Psychosocial treatments to promote functional recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2009;35:347–361. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick B, Messias E, Harvey PD, Fernandez-Egea E, Bowie CR. Is schizophrenia a syndrome of accelerated aging? Schizophr. Bull. 2008;34:1024–1032. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kongs SK, Thompson LL, Iverson GL, Heaton RK. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test – 64 card version (WCST-64) Psychological Assessment Resources; Florida: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kupfer DJ. Size of treatment effects and their importance to clinical research and practice. Biol. Psychiatry. 2006;59:990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marwaha S, Johnson S. Schizophrenia and employment – a review. Soc. Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2004;39:337–349. doi: 10.1007/s00127-004-0762-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausbach BT, Bowie CR, Harvey PD, Twamley EW, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Usefulness of the UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA) for predicting residential independence in patients with chronic schizophrenia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008;42:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: a review and heuristic model. Schizophr. Res. 2004;70:147–173. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Aalto S, Becker DR, Ogden JS, Wolfe RS, Shiavo D, Wallace CJ, Xie H. The effectiveness of skills training for improving outcomes in supported employment. Psychiatr. Serv. 2005;56:1254–1260. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueser KT, Clark RE, Haines M, Drake RE, McHugo GJ, Bond GR, Essock SM, Becker DR, Wolfe R, Swain K. The Hartford study of supported employment for persons with severe mental illness. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2004;72:479–490. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oltmanns TF, Neale JM. Schizophrenic performance when distractors are present: attentional deficit or differential task difficulty? J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1975;84:205–209. doi: 10.1037/h0076721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer BW, Heaton SC, Jeste DV. Older patients with schizophrenia: challenges in the coming decades. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999;50:1178–1183. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Jeste DV. The potential impact of the baby-boom generation on substance abuse among elderly persons. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999;100:126–135. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD performance-based skills assessment (UPSA): Development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr. Bull. 2001;27:235–245. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead-Reitan neuropsychological test battery: theory and clinical interpretation. second ed. Neuropsychology Press; Arizona: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Jeste DV, Lehman AF. Vocational rehabilitation in schizophrenia: A literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2003;191:515–523. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000082213.42509.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twamley EW, Narvaez JM, Becker DR, Bartels SJ, Jeste DV. Supported employment for middle-aged and older people with schizophrenia. Am. J Psychiatr. Rehabil. 2008;11:76–89. doi: 10.1080/15487760701853326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Third Edition (WAIS-III) The Psychological Corporation; Texas: 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale – Third Edition (WMS-III) The Psychological Corporation; Texas: 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, Aggarwal J. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66:1122–1129. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.