Abstract

Mu-opioid receptors (MOR) are the therapeutic target for opiate analgesic drugs and also mediate many of the side-effects and addiction liability of these compounds. MOR is a seven-transmembrane domain receptor that couples to intracellular signaling molecules by activating heterotrimeric G proteins. However, the receptor and G protein do not function in isolation but their activities are moderated by several accessory and scaffolding proteins. One important group of accessory proteins is the regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protein family, a large family of more than thirty members which bind to the activated Gα subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein and serve to accelerate signal termination. This action negatively modulates receptor signaling and subsequent behavior. Several members of this family, in particular RGS4 and RGS9-2 have been demonstrated to influence MOR signaling and morphine-induced behaviors, including reward. Moreover, this interaction is not unidirectional since morphine has been demonstrated to modulate expression levels of RGS proteins, especially RGS4 and RGS9-2, in a tissue and time dependent manner. In this article, I will discuss our work on the regulation of MOR signaling by RGS protein activity in cultured cell systems in the context of other in vitro and behavioral studies. In addition I will consider implications of the bi-directional interaction between MOR receptor activation and RGS protein activity and whether RGS proteins might provide a suitable and novel target for medications to manage addictive behaviors.

Keywords: RGS proteins, mu-opioid receptors, G-proteins, morphine

1. Introduction

1.1 The mu-opioid receptor and heterotrimeric G proteins

The mu-opioid receptor (MOR) is responsible for most if not all the observed acute and chronic effects of morphine and related clinically useful and/or abused opioids, such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and heroin, including the addictive properties of this class of compounds. The receptor itself is a seven-transmembrane domain G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that interacts with heterotrimeric G proteins (Laugwitz et al., 1993; Clark et al., 2006). These G proteins link agonist-induced changes in MOR conformation to downstream signaling events that ultimately result in the acute actions of morphine including analgesia, euphoria, constipation and respiratory depression. Continued activation of these signaling pathways leads to homeostatic changes that result in tolerance and the opioid-dependent state (Borgland, 2001; Chao and Nestler, 2004; von Zastrow, 2010).

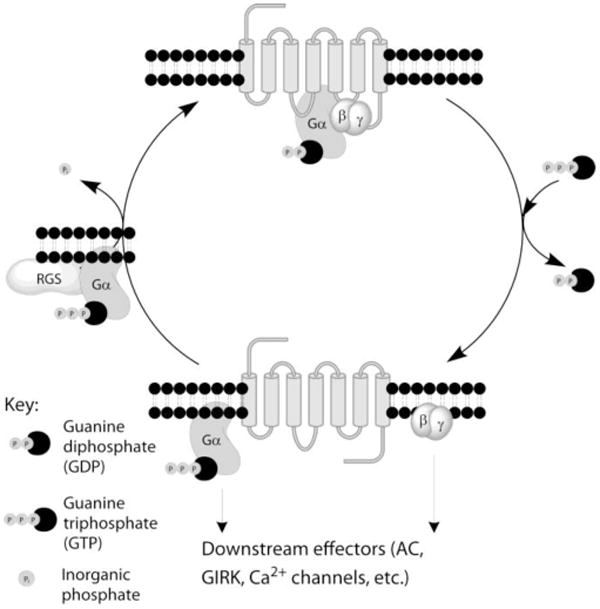

Heterotrimeric G proteins comprise three proteins, one Gα subunit, and a heterodimer of β and γ subunits. MOR interacts with the Gαi/o class of adenylate cyclase inhibitory Gα proteins (Clark et al., 2006), that is comprised of Gαi (which exists in three forms Gαi1, 2, and 3), Gαo (which has two splice variants A and B) and Gαz. The associated βγ heterodimer is comprised of one of the five different β and one of the twelve different γ proteins. In the resting state the Gα subunit is bound to the guanine nucleotide GDP and is in complex with the β and γ subunits (Figure 1). Activation of MOR by agonists leads to dissociation of GDP from the Gα subunit, which is replaced by GTP, and separation of the Gα-GTP from the βγ heterodimer. The now active Gα-GTP and βγ subunit complex interact with intracellular signaling proteins, including inwardly rectifying potassium channels, calcium channels, phospholipase C and the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway as well as a variety of adenylate cyclase isoforms, to generate physiological responses. The intracellular signal is terminated by endogenous GTPase activity of the Gα subunit which hydrolyses the Gα bound GTP to GDP. Gα-GDP can no longer activate effector proteins and moreover, re-associates with the βγ heterodimer to terminate βγ signaling and reform the GDP-bound heterotrimer. This recycles heterotrimeric G protein substrate for a subsequent round of receptor activation (Figure 1). The enzymatic GTPase activity of the Gαi/o subunits is slow with a GTP turnover rate of 2 to 5 per minute. This is not sufficiently rapid to turn off the signal and allow responses to subsequent incoming signals. However, the rate of hydrolysis of GTP is accelerated approximately 100-fold by the binding of a Regulator of G Protein Signaling (RGS) protein to the active GTP-bound Gα subunit. RGS proteins thus function as GTPase accelerating proteins (GAPs) and, by rapidly removing the active Gα-GTP and βγ species, act as negative regulators of GPCR signaling; this also likely applies to constitutive, ligand independent, signaling (Welsby et al., 2002). RGS protein GAP activity is seen at Gαi/o proteins which interact with MOR and also at the Gαq family of G proteins that link a variety of GPCRs to phospholipase C pathways, but not at Gαs proteins which have an efficient intrinsic GTPase activity.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the G protein cycle. The seven-transmembrane domain MOR is associated with the Gαβγ heterotrimeric G protein with the Gα subunit bound to GDP. Activation of MOR by agonist promotes the exchange of GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit and separation of the Gα and βγ subunits which interact with downstream effectors. Active Gα-GTP is hydrolyzed by the GTPase activity of the Gα subunit to provide Gα-GDP which recombines with the βγ subunits thus terminating signaling. This process is accelerated by the GAP activity of the RGS protein binding to the GTP-bound Gα subunit.

Many addictive substances, including opiates, exert their effects by acting directly or indirectly at GPCRs. Since RGS proteins negatively regulate GPCR signaling these accessory proteins have been implicated in the actions of opiates (for reviews see Traynor and Neubig, 2005; Hooks et al., 2008; Traynor, 2010).

1.2. RGS proteins

There are more than 30 mammalian RGS proteins, defined by the presence of an RH (RGS homology) domain; a region of 125 amino-acids that binds to the GTP-bound Gα subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein and accelerates GTP hydrolysis (Hollinger and Hepler, 2002). RGS proteins are divided into several families based on RH domain homology and existence of a variety of additional structural domains (Table 1). Smaller RGS proteins in the R4 and RZ families consist essentially of the RH domain, although the short N-terminus may be important for receptor recognition and binding. Other RGS proteins have more complex structures with various protein-protein binding sites. A good example is the R7 family, especially RGS9-2 which is highly expressed in the striatum (Gold et al., 1997; Granneman et al., 1998) and in a number of studies has been linked to the action of opiates. RGS9-2 contains a DEP (disheveled, Egl-10, pleckstrin) domain that binds to bind R7-binding protein (R7BP; Martemyanov et al., 2005; Ballon et al., 2006) and a G protein gamma-like (GGL) domain that binds the G protein β subunit β5 (Gβ5; Witherow et al., 2000). These protein partners are essential to provide membrane association and stabilize RGS9-2 against degradation (Drenan et al., 2005; Song et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2003). Several proteins containing RH domains lack GAP activity but contribute to signaling by virtue of their ability to bind and/or scaffold Gα subunits. For instance, the RH domain of GRK2 (GPCR kinase 2) binds Gαq and inhibits its ability to activate phospholipase C (Day et al., 2004). The Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEFs) bind Gα12 and Gα13 proteins (Kozasa et al., 1998) and couple receptors to Rho-mediated signaling pathways necessary for cell growth, proliferation, and differentiation.

Table 1. RGS protein families with GAP activitya and family members reported to modulate MOR signaling and/or behavior.

| Family | Members | Structured | RGS proteins with effects on MOR signaling and/or behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RZ | RGS17,19,20b | N-terminal cysteine string | RGS19 | Attenuates AC inhibition in HEK cellse |

| RGS17; RGS20 | Antisense knockdown mice show increases in antinociception and tolerance f,g | |||

|

| ||||

| R4 | RGS1,2,3c,4,5, 8,13,16,18,21 | N-terminal amphipathic helix | RGS1 | Attenuates AC inhibition in HEK cellse |

| RGS2 | Increases pigment aggregation in melanophores in vitroh; attenuates AC inhibition in HEK cellse | |||

| RGS4 | Decreases signaling to AC in heterologous cell systems e,i,j Conditional knockout of RGS4 in NAc increases withdrawal signs in micek | |||

| RGS | Acceleration of GTPase activityl; inhibition of ACi in C6 cells | |||

|

| ||||

| R7 | RGS 6,7,9,11 | GGL + DEP + R7H domains | RGS8 6, 7 11 | Antisense knockdown enhances morphine-mediated antinociception in themousem |

| RGS9-2 | RGS9-2 knockdown or knockout in mice gives enhanced antinociception, delayed tolerancem,n increased withdrawal symptoms and enhanced rewardn. Decreased antinociception also reportedo,p. Overexpression of RGS9-2 in HEK cells delays MOR internalizationq, inhibits ERK phosphorylationq and attenuates AC inhibitionq | |||

|

| ||||

| R12 | RGS10,12,14 | Variable - PDZ, RBD and GoLoco domains | RGS10 | Attenuates AC inhibition in HEK cellse |

Several proteins with RH domains do not act as GTPase accelerating proteins but bind Gα proteins and act link Gα signaling to other pathways or prevent signaling of the specific Gα, these include Axin, Conduction, P115RhoGef and GRK2 and 3.

RGS17 and RGS20 are also known as RGSZ2 and and RGSZ1 respectively; RGS19 is also known as GAIP (Gα-interacting protein).

RGS3 is much larger than other members of the R4 family and has splice variants, some of which include a PDZ domain.

Abbreviations: DEP (disheveled, Egl-10, pleckstrin) domain; GGL (G protein gamma-like) domain; GoLoco (G-protein regulatory) domain; RBD (Raf-like Ras-binding) domain; R7H (R7 homology) domain.

2. RGS proteins and opioid pharmacology

Not long after the discovery of mammalian RGS proteins it was shown that they were able to act as GAPs for MOR signaling both in vivo and in vitro (Garzon et al., 2001; Clark et al., 2003; Zachariou et al., 2003). On the other hand, as stated above, there are numerous RGS proteins with GAP activity. Consequently, it is difficult to identify the individual RGS protein or proteins that might be specifically responsible for the negative modulation of opioid signaling in a given tissue and therefore relevant to a particular physiological response. Certainly, there are so many RGS proteins that redundancy is likely. For example, RGS2, RGS4, RGS6, RGS7, RGS8, RGS9-2, RGS6, RGS7, RGS11, RGS19 and RGS20 have all been reported to act as GAPS for MOR signaling in different systems (Table 1). Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain if an observed lack of physiological effect in response to knockdown or knockout of a single RGS protein is meaningful. The RGS4 knockout mouse model provides a good example. This mouse shows little if any phenotypic behavioral responses to morphine compared with wild-type littermates (Grillet et al., 2005; Han et al., 2010), yet profound effects of RGS4 on morphine signaling in vitro have been reported (Georgoussi et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2007; Talbot et al., 2010b). Conversely, the discrete localization of many RGS proteins, especially in the central nervous system (Gold et al., 1997), together with the complex nature of certain RGS protein families, does indicate potential selectivity for certain receptors and their cognate heterotrimeric G proteins. Indeed, selectivity is enhanced depending on the Gα protein subtype involved - members of the R7 family are selective for Gαo (Posner et al., 1999; Lan et al., 2000) - and there is also evidence for specificity of interaction between certain GPCRs and RGS proteins (Xu et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2002; Bernstein et al., 2004; Saitoh et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2009).

There are currently no useful pharmacological inhibitors of RGS proteins available with which to probe roles for these proteins, although progress is being made in this area (Roman et al., 2007; Blazer et al., 2010; Blazer et al., 2011). In this paper I will discuss two genetic approaches to the study of the action of RGS proteins on MOR pharmacology. The first approach employs mutated Gα proteins that are non-responsive to the GAP activity of all RGS proteins (Clark and Traynor, 2004) which has the benefit of by-passing problems of redundancy. The second approach is knockout (or knockdown) of individual RGS proteins which can provide more direct evidence for roles of individual RGS proteins, if the correct RGS is chosen for study.

2.1. Use of RGS-insensitive mutants of Gα proteins to study opioid receptor signaling

There is a considerable degree of differential distribution of RGS protein family members across brain regions (Gold et al., 1997), but even so several types of RGS proteins are expressed in regions of the rodent brain that express MOR (Traynor and Neubig, 2005). Although no direct data are available at the single neuron level there are likely to be several RGS proteins co-expressed with MOR. Certainly, in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells that endogenously express MOR we have identified the presence of RGS2, RGS3, RGS4, RGS5, RGS6, RGS7, RGS8 and RGS19 by RTPCR (Wang and Traynor, unpublished observations). It is therefore difficult to study each individual RGS protein for its ability to act as a GAP for MOR signaling because: a) there are potentially many RGS partners for MOR signaling, although one can make educated guesses (see below); b) there may be redundancy in the system such that knocking down one particular RGS proteins does not mean that RGS GAP activity at MOR is inhibited; c) there is a lack of tools, especially antibodies for RGS proteins. To circumvent these problems the approach we have taken is to use mutated Gαi/o proteins that are insensitive to the GAP activity of all RGS proteins.

RGS proteins have GAP activity by virtue of their ability to bind to the Gα subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein in its active GTP bound conformation (Tesmer et al., 1997). Binding and therefore GAP activity can be prevented by replacing Gly184 in the switch 1 region of a Gα protein with Ser (Lan et al., 1998). This leads to an increased life-time of Gα-GTP and βγ subunits, accumulation of these active signaling molecules and enhanced interaction with downstream effectors. Heterologous expression of the mutant Gα in cell systems (Clark et al., 2003) or genetic knock-in of the mutant Gα in mice (Huang et al., 2006; Talbot et al., 2010a) provides a powerful technique that allows observation of the action of the role of GAP activity at a heterotrimeric G protein mediated pathway and/or behavior, regardless of which RGS protein is carrying out this function. Moreover, since only one Gα protein is mutated any change in signaling or behavior observed can be ascribed to that particular Gα subtype.

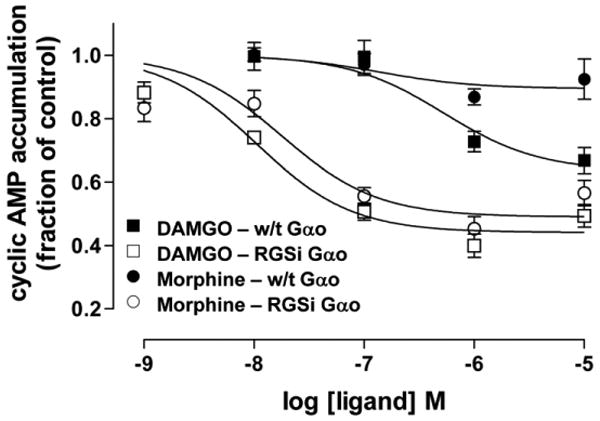

In rat C6 glioma cells that heterologously express MOR (C6MOR) and RGS-insensitive Gαo, the concentration-effect curve for morphine to inhibit adenylate cyclase, which occurs via Gα-GTP, is dramatically altered, giving both an increase in potency and efficacy (Clark et al., 2003; Figure 2). This approach highlights the very powerful ability of RGS protein GAP action to negatively regulate MOR signaling. A similar effect is observed for the βγ-mediated activation of MAPK. Strangely, the release of intracellular calcium which also occurs downstream of βγ is not altered and in some instances is decreased. This unexpected phenomenon has also been observed at the dopamine D2 receptor (Boutet-Robinet et al., 2003). The reason for this difference between two pathways that are both activated via the βγ heterodimer can be explained by a kinetic scaffolding mechanism whereby the close proximity of receptor, effector and RGS, enhances the response by renewing heterotrimeric G protein substrate (Zhong et al., 2003; Clark et al., 2003). Importantly, this differential effect on signaling pathways means that the GAP activity of RGS proteins contributes to the process of signaling pathway selection in a cell following agonist action at MOR.

Figure 2.

MOR agonists have a higher potency and maximal inhibition of cAMP accumulation (a measure of adenylate cyclase activity) in cells expressing RGS-insensitive Gαo (RGSi-Gαo) than in cells expressing wild-type (w/t) Gαo. The effect is more pronounced for the partial agonist morphine. This research was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry by Clark and colleagues; Endogenous RGS Protein Action Modulates μ-Opioid Signaling through Gαo: effects on adenylate cyclase, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, and intracellular calcium pathways (Clark et al., 2003). © The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Inhibition of GAP activity in C6MOR cells has a more profound effect on the maximal response to morphine than the higher efficacy MOR peptidic agonist DAMGO and so knockdown of RGS activity increases the maximal effect of morphine relative to DAMGO. The knockout of RGS activity in these cells has an even greater effect on the maximal response of less efficacious partial agonists such as buprenorphine and nalbuphine. As a result, depending on the level of RGS protein activity buprenorphine may be seen as a full or partial agonist (Clark et al., 2008). This indicates that RGS protein activity is an important cellular component that determines observed maximal response to agonists, in addition to other tissue dependent determinants such as receptor number and G protein level (Kenakin, 1997). By extrapolation therefore, in vivo inhibition of RGS protein GAP activity would be predicted to have a more profound effect in promoting one behavior (e.g., analgesia) without necessarily increasing an unwanted behavior (e.g., respiratory depression) depending on the efficacy requirements of the systems (Traynor, 2004; Blazer and Neubig, 2009). Further selectivity might be gained by inhibition of defined RGS proteins and so it can be speculated that enhancement of the maximal analgesic response to morphine by inhibition of a certain RGS protein may occur without enhancement of other responses, e.g., constipation or reward, that might be modulated by a different RGS protein.

Since blockade of RGS protein GAP activity increases signaling it was not unexpected to observe a similar increase in the development of tolerance in a heterologous cell expression system in the presence of RGS-insensitive Goto protein (Clark and Traynor, 2005). This indicates that endogenous RGS protein action serves to lessen tolerance development. However, this apparently simple idea is confounded by the fact that RGS proteins decrease opioid signaling to downstream effectors and this may appear as tolerance, thus the observed outcome is not easy to predict. In the few behavioral experiments that have been performed, in vivo knockdown or knockout of R7 family proteins in mice delays the development of antinociceptive tolerance (Zachariou et al., 2003; Garzon et al., 2001; Garzon et al., 2003). This is presumably because acute signaling leading to antinociception pathways is enhanced to a greater extent than the signaling pathways leading to antinociceptive tolerance. Furthermore, it has also been shown that morphine treatment in vivo up-regulates RGS9-2 (see section 3). This would increase the negative modulation of MOR signaling and so provide an additional mechanism for tolerance (Zachariou et al., 2003).

Use of RGS-insensitive Gαo protein in heterologously expressed cell systems also demonstrates that endogenous RGS proteins limit the development of opioid dependence. At the single cell level opioid dependence can be measured as a sensitization of adenylate cyclase activity on withdrawal of chronic drug exposure (Watts, 2002; Clark et al., 2004; Divin et al., 2009). This may be related to dependence in vivo (Bohn et al., 2000; Zachariou et al., 2008). In this case behavioral results agree with the cellular findings. Thus, the RGS9-2 knockout mouse shows enhanced morphine withdrawal, indicating a greater degree of physical dependence (Zachariou et al., 2003), and one strain of RGS4 knockout mice show increases in several withdrawal behaviors (Han et al., 2010).

2.2. Roles of individual RGS proteins on opioid signaling

An alternative approach is to study individual RGS proteins for their effects on MOR signaling and behavior. This suffers from the problems of redundancy and of having to identify the correct RGS protein partner, but can provide more direct evidence as to those RGS protein(s) that are relevant to a particular response. I will concentrate on two RGS proteins, RGS4 and RGS9-2 for which there is considerable evidence of modulation of MOR agonist signaling and/or behavior.

2.2.1. RGS4

RGS4 is a small RGS protein and is essentially a non-selective GAP that acts at the Gαi/o, Gαz and Gαq families of Gα proteins (Zhong and Neubig, 2001; Zheng et al., 1999). It is abundant and expressed in many brain regions (Gold et al., 1997; Nomoto et al., 1997) including striatum, thalamus, locus coeruleus and dorsal horn of the spinal cord which express high levels of MOR (Mansour et al., 1995). RGS4 is up-regulated in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord following nerve injury (Garnier et al., 2003) a change that may contribute to the lack of effectiveness of morphine in neuropathic pain.

RGS4 has been shown to act as a GAP for MOR signaling in in vitro assays using purified proteins and in several heterologous expression systems (Garnier et al., 2003; Georgoussi et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2007; Talbot et al., 2010b; Ippolito et al., 2002). RGS4 has also been demonstrated to immunoprecipitate with MOR (Leontiadis et al., 2009). In contrast, experiments using RGS4 constitutive knockout mice have shown little phenotypic behavior towards morphine (Grillet et al., 2005; Han et al., 2010). However, mice with a selective knockout of RGS4 in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) do show a small increase in sensitivity to the rewarding effects of morphine as measured by place preference assay, and in the development of locomotor sensitization (Han et al., 2010). As a compromise between these systems we have studied RGS4 activity in SH-SY5Y cells. These cells express a high concentration of RGS4 as well as MOR and delta opioid receptors (DOR). Expression of RGS-insensitive Gαo protein in these cells confirmed that MOR signaling is negatively modulated by endogenous GAP activity. Knockdown of RGS4 protein by lentiviral delivery of short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting the RGS4 gene did not alter MOR signaling whereas DOR and muscarinic M3 receptor signaling were markedly increased (Wang et al., 2009). Subsequent immunoprecipitation studies in HEK cells indicated that the C-terminal tail of the receptor governs the selectivity of RGS4 (Wang et al., 2009), although this interaction may not be direct, but via scaffolding proteins such as spinophilin (Wang et al., 2005). This finding agrees with the lack of phenotypic behavior towards morphine in RGS4 knockout mice, but disagrees with other in vitro data (Xie et al., 2007; Talbot et al., 2010b; Ippolito et al., 2002; Georgoussi et al., 2006). One explanation for these disparate findings is that MOR is promiscuous with regard to RGS protein activity, possibly because the MOR-Gα-RGS4 interaction is of lower affinity that the DOR-Gα-RGS4 interaction (Wang et al., 2009) and therefore MOR signaling simply employs an alternative RGS protein, i.e., a redundancy.

2.2.2. RGS9-2

RGS9-2 is a splice variant of the RGS9 gene (Rahman et al., 2003; Granneman et al., 1998) that acts as a GAP at Gαi/o but not Gαq proteins. It is highly, but not exclusively, expressed in the striatum in regions similar to many dopamine specific proteins (Greengard et al., 1999). RGS9-2 acts. RGS9-2 has therefore been considered a likely partner for GPCRs involved in mediating the actions of drugs of abuse, including MOR (Traynor and Neubig, 2005; Hooks et al., 2008; Traynor et al., 2009). This of course does not mean that RGS9-2 must modulate MOR signaling. In fact, there has been no direct identification of the co-localization of both proteins within a single neuron, although in separate studies RGS9-2 (Cabrera-Vera et al., 2004) and MOR (Wang et al., 1997; Jabourian et al., 2005) have been identified in medium spiny neurons and cholinergic interneurons in rat striatum. Certainly, at a gross level RGS9-2 is expressed throughout the dorsal and ventral striatum (Gold et al., 1997) whereas the distribution of MOR is patchy (Mansour et al., 1995). Regardless, RGS9-2 has been shown to be an effective GAP for MOR signaling in vitro and to alter MOR- mediated behaviors in vivo.

The modulation of MOR signaling by RGS9-2 is less contentious than for RGS4. Mice null for the RGS9 gene show increased sensitivity to morphine in conditioned place preference assays and enhanced locomotor sensitization to morphine – which can be reversed by restoring RGS9-2 levels (but not RGS4 levels) in the NAc (Zachariou et al., 2003). Since RGS9-2 markedly alters stimulant behaviors and acts as a negative modulator of dopamine D2 signaling (Rahman et al., 2003; Cabrera-Vera et al., 2004) the effects of the RGS9 knockout on these opioid-mediated behaviors may be indirect. On the other hand RGS9-2 is also found, albeit at lower levels, in the periaquaductal gray (PAG) and in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. RGS9 knockout mice show enhanced morphine antinociception compared to their wild-type littermates and antinociceptive tolerance is slowed (Zachariou et al., 2003). Moreover, RGS9-2 is an efficient GAP for MOR signaling in heterologous expression systems (Psifogeorgou et al., 2007) suggesting at least some of the actions of RGS9 -2 on MOR-mediated behaviors may be direct.

3. Opioid regulation of RGS proteins

A number of studies have demonstrated that RGS9-2 and RGS4 expression are altered at the level of either protein or message following MOR agonist treatment in rodents, although the findings are variable depending on time of agonist exposure and brain region studied and reports are inconsistent. In the mouse, acute morphine treatment has been reported to up-regulate RGS9-2 protein in the NAc, PAG and spinal cord while chronic morphine down-regulates RGS9-2 protein in these regions (Zachariou et al., 2003). In contrast Lopez-Fando and colleagues (2005) show in the mouse that chronic morphine leads to increases in both RGS9-2 protein and message in the PAG, thalamus and striatum. The situation is even more complex with RGS4. For example, it has been reported that following acute morphine treatment in the rat there is an increase in RGS4 message in the NAc, which disagrees with a decrease in RGS4 protein reported to occur in this region in the mouse (Han et al., 2010). There is also a decrease in RGS4 mRNA in the locus coereulus (LC) that becomes an increase as morphine treatment is continued (Bishop et al., 2002). In contrast, another group (Gold et al., 2003) reports no change in RGS4 mRNA in the rat LC with chronic morphine treatment, but a 2-fold increase in RGS4 protein. Moreover, RGS4 protein reverts to resting levels following naltrexone-precipitated withdrawal, even though there is a marked increase in RGS4 mRNA under these conditions (Gold et al., 2003). Taken together these findings indicate a disconnection between changes at the mRNA and protein level.

It has been shown that RGS4 mRNA is increased by morphine treatment in PC12 cells heterologously expressing MOR (Nakagawa et al., 2001). Consequently, to study MOR agonist regulation of RGS proteins we again turned to the SHSY5Y cell system. Unlike the PC12 cell system we observed no up-regulation of RGS4 following acute MOR agonist treatment, but did find that chronic treatment with the MOR agonists morphine or DAMGO led to a marked down regulation of RGS4 at the protein level, with no change in mRNA (Wang and Traynor, 2011), again indicating a disconnect between message and protein. This reduction in RGS4 was surprising, given that RGS4 does not modulate MOR signaling in these cells, but could support our hypothesis that there is redundancy of GAP activity at MOR (Wang et al., 2009). RGS4 is an unstable protein and is readily degraded by ubiquitination. In the presence of MOR agonist there is increased ubiquitination and degradation. The reduction in RGS4 protein was accompanied by marked MOR down-regulation, possible suggesting that RGS4 is stabilized in a complex with receptor and Gα protein, especially since the N-teminus is the site for both ubiquitination (Davydov et al., 2000) and for receptor interaction (Zeng et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2009) This reduction in cellular RGS4 levels causes enhanced signaling at co-expressed DOR and M3 receptors which are negatively modulated by RGS4, but not α2 adrenoceptors or bradykinin BK2 receptors which are not sensitive to RGS4 modulation (Figure 4; Wang and Traynor, 2011). The findings indicate that RGS4 modulation provides a mechanism for cross-talk between co-expressed receptors and may contribute to homeostatic changes in response to chronic opioid exposure. Indeed, following opioid-mediated reduction of RGS4 the muscarinic agonist carbachol acting via Gαq stimulates calcium-sensitive adenylate cyclase enzymes (AC1 and AC8; Figure4) which could be a contributor to the adenylate cyclase sensitization that occurs in response to chronic MOR agonist.

4. Conclusions – relevance to addiction

The interaction between RGS proteins and MOR appears to be a bi-directional. Opioid receptor signaling is negatively modulated by RGS protein activity and at least some RGS proteins are in turn regulated by MOR activity, though this may be up or down-regulation depending on the circumstances and the timing of the response. Both have implications for the pharmacology of morphine. The changes in RGS proteins caused by MOR agonists not only serve to alter MOR signaling but have the potential to regulate signaling at receptors co-expressed with MOR; this could very well have implications for maintaining cellular homeostasis in the morphine-dependent state. Knockout of RGS9-2 or RGS4 protein activity in the NAc enhances morphine-induced conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization, and consequently, compounds that promote RGS activity -for example by stabilization of the protein (Wang and Traynor, 2011) would be expected to reduce rewarding behaviors and presumably potential to cause addiction. However, since RGS9-2 also negatively modulates the analgesic effect of morphine (Zachariou et al., 2003) enhancement of RGS9-2 activity will decrease the analgesic effectiveness of morphine. On the other hand, a recent report suggests that, depending on the site of action (spinal versus supraspinal) morphine's analgesic activity may be enhanced or inhibited by RGS9-2 (Papachatzaki et al., 2011).

The rewarding effects of MOR agonists involve an inhibition of GABA release in the ventral tegmental area (VTA), leading to disinhibition of dopaminergic projections to the NAc and increased release of dopamine, together with a direct effect in the NAc to increase dopamine release (Koob et al., 1998). There are several RGS proteins expressed in these regions including RGS2, RGS4, RGS8, RGS5, RGS7, RGS9-2, RGS10 in the NAc, and RGS2, RGS3, RGS4, RGS6, RGS7, RGS8 in the VTA (Gold et al., 1997; Wang and Traynor, unpublished observations) and it will be important to understand their role(s) in the addictive process. As we learn more about individual RGS proteins and their role in MOR signaling and behaviors, and as inhibitors and activators are discovered, we will learn if these proteins do indeed represent targets for a novel approach to the management of opiate addiction.

Figure 3.

Schematic to indicate how MOR agonist-induced down-regulation of RGS4 protein which negatively modulates signaling to DOR and muscarinic M3 receptors, allows for increased signaling at these receptors, including exposure of an ability of M3 receptors to stimulate AC activity via increased Ca2+ release. This figure was originally published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry by Wang and Traynor; Opioid-Induced Down-Regulation of RGS4: Role of ubiquitination and Implications for receptor cross-talk (Wang and Traynor, 2009). © The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: Funding for this study was provided by DA 04087 and the University of Michigan Substance Abuse Research Center. Neither funding source had any input into the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit for publication.

Research reviewed from the author's laboratory was supported by DA 04087. I thank members of the laboratory for careful and critical reading of the manuscript and Jennifer Lamberts for Figure 1.

Footnotes

Contributors: John Traynor wrote this report. Much of the data mentioned in this review was collected by members of the Traynor laboratory at the University of Michigan.

Conflict of interest: This author has no conflict of interest.

This paper was presented in a symposium at the Behavior, Biology, and Chemistry: Translational Research in Addiction meeting on March 5, 2011 in San Antonio, TX entitled “New concepts in mu-opioid pharmacology -implications for addiction and its management.”

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ballon DR, Flanary PL, Gladue DP, Konopka JB, Dohlman HG, Thorner J. DEP-domain-mediated regulation of GPCR signaling responses. Cell. 2006;126:1079–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer LL, Neubig RR. Small molecule protein-protein interaction inhibitors as CNS therapeutic agents: current progress and future hurdles. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;34:126–141. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer LL, Roman DL, Chung A, Larsen MJ, Greedy BM, Husbands SM, Neubig RR. Reversible, allosteric small-molecule inhibitors of regulator of G protein signaling proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:524–533. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer LL, Zhang H, Casey EM, Husbands SM, Neubig RR. A nanomolar-potency small molecule inhibitor of regulator of G-protein signaling proteins. Biochemistry. 2011;50:3181–3192. doi: 10.1021/bi1019622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LS, Ramineni S, Hague C, Cladman W, Chidiac P, Levey AI, Hepler JR. RGS2 binds directly and selectively to the M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor third intracellular loop to modulate Gq/11alpha signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:21248–21256. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312407200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop GB, Cullinan WE, Curran E, Gutstein HB. Abused drugs modulate RGS4 mRNA levels in rat brain: comparison between acute drug treatment and a drug challenge after chronic treatment. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;10:334–343. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–723. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgland SL. Acute opioid receptor desensitization and tolerance: is there a link? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:147–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boutet-Robinet EA, Finana F, Wurch T, Pauwels PJ, De Vries L. Endogenous RGS proteins facilitate dopamine D(2S) receptor coupling to G(alphao) proteins and Ca2+ responses in CHO-K1 cells. FEBS Lett. 2003;533:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Vera TM, Hernandez S, Earls LR, Medkova M, Sundgren-Andersson AK, Surmeier DJ, Hamm HE. RGS9-2 modulates D2 dopamine receptor-mediated Ca2+ channel inhibition in rat striatal cholinergic interneurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16339–16344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407416101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao J, Nestler EJ. Molecular neurobiology of drug addiction. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:113–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.55.091902.103730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CK, Eversole-Cire P, Zhang H, Mancino V, Chen YJ, He W, Wensel TG, Simon MI. Instability of GGL domain-containing RGS proteins in mice lacking the G protein beta-subunit Gbeta5. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6604–6609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631825100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Furman CA, Gilson TD, Traynor JR. Comparison of the relative efficacy and potency of mu-opioid agonists to activate Galpha(i/o) proteins containing a pertussis toxin-insensitive mutation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:858–864. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Harrison C, Zhong H, Neubig RR, Traynor JR. Endogenous RGS protein action modulates mu-opioid signaling through Galphao Effects on adenylyl cyclase, extracellular signal-regulated kinases, and intracellular calcium pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9418–9425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Linderman JJ, Traynor JR. Endogenous regulators of G protein signaling differentially modulate full and partial mu-opioid agonists at adenylyl cyclase as predicted by a collision coupling model. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1538–1548. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.043547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Neubig RR, Traynor JR. Endogenous regulator of G protein signaling proteins suppress Galphao-dependent, mu-opioid agonist-mediated adenylyl cyclase supersensitization. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;310:215–222. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.064824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Traynor JR. Assays for G-protein-coupled receptor signaling using RGS-insensitive Galpha subunits. Methods Enzymol. 2004;389:155–169. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)89010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MJ, Traynor JR. Endogenous regulator of g protein signaling proteins reduce mu-opioid receptor desensitization and down-regulation and adenylyl cyclase tolerance in C6 cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:809–815. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davydov IV, Varshavsky A. RGS4 is arginylated and degraded by the N-end rule pathway in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22931–22941. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001605200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day PW, Tesmer JJ, Sterne-Marr R, Freeman LC, Benovic JL, Wedegaertner PB. Characterization of the GRK2 binding site of Galphaq. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:53643–53652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401438200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divin MF, Bradbury FA, Carroll FI, Traynor JR. Neutral antagonist activity of naltrexone and 6beta-naltrexol in naive and opioid-dependent C6 cells expressing a mu-opioid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156:1044–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenan RM, Doupnik CA, Boyle MP, Muglia LJ, Huettner JE, Linder ME, Blumer KJ. Palmitoylation regulates plasma membrane-nuclear shuttling of R7BP, a novel membrane anchor for the RGS7 family. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:623–633. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnier M, Zaratin PF, Ficalora G, Valente M, Fontanella L, Rhee MH, Blumer KJ, Scheideler MA. Up-regulation of regulator of G protein signaling 4 expression in a model of neuropathic pain and insensitivity to morphine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1299–1306. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon J, Rodriguez-Munoz M, Lopez-Fando A, Sanchez-Blazquez P. The RGSZ2 protein exists in a complex with mu-opioid receptors and regulates the desensitizing capacity of Gz proteins. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;30:1632–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon J, Rodriguez-Munoz M, Lopez-Fando A, Garcia-Espana A, Sanchez-Blazquez P. RGSZ1 and GAIP regulate mu- but not delta-opioid receptors in mouse CNS: role in tachyphylaxis and acute tolerance. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004;29:1091–1104. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon J, Lopez-Fando A, Sanchez-Blazquez P. The R7 subfamily of RGS proteins assists tachyphylaxis and acute tolerance at mu-opioid receptors. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2003;28:1983–1990. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garzon J, Rodriguez-Diaz M, Lopez-Fando A, Sanchez-Blazquez P. RGS9 proteins facilitate acute tolerance to mu-opioid effects. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;13:801–811. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2000.01444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgoussi Z, Leontiadis L, Mazarakou G, Merkouris M, Hyde K, Hamm H. Selective interactions between G protein subunits and RGS4 with the C-terminal domains of the mu- and delta-opioid receptors regulate opioid receptor signaling. Cell Signal. 2006;18:771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SJ, Han MH, Herman AE, Ni YG, Pudiak CM, Aghajanian GK, Liu RJ, Potts BW, Mumby SM, Nestler EJ. Regulation of RGS proteins by chronic morphine in rat locus coeruleus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold SJ, Ni YG, Dohlman HG, Nestler EJ. Regulators of G-protein signaling (RGS) proteins: region-specific expression of nine subtypes in rat brain. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8024–8037. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-20-08024.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granneman JG, Zhai Y, Zhu Z, Bannon MJ, Burchett SA, Schmidt CJ, Andrade R, Cooper J. Molecular characterization of human and rat RGS 9L, a novel splice variant enriched in dopamine target regions, and chromosomal localization of the RGS 9 gene. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;54:687–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greengard P, Allen PB, Nairn AC. Beyond the dopamine receptor: the DARPP-32/protein phosphatase-1 cascade. Neuron. 1999;23:435–447. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80798-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillet N, Pattyn A, Contet C, Kieffer BL, Goridis C, Brunet JF. Generation and characterization of RGS4 mutant mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:4221–4228. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.10.4221-4228.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Renthal W, Ring RH, Rahman Z, Psifogeorgou K, Howland D, Birnbaum S, Young K, Neve R, Nestler EJ, Zachariou V. Brain region specific actions of regulator of G protein signaling 4 oppose morphine reward and dependence but promote analgesia. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:761–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger S, Hepler JR. Cellular regulation of RGS proteins: modulators and integrators of G protein signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:527–559. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.3.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks SB, Martemyanov K, Zachariou V. A role of RGS proteins in drug addiction. Biochem Pharmacol. 2008;75:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Fu Y, Charbeneau RA, Saunders TL, Taylor DK, Hankenson KD, Russell MW, D'Alecy LG, Neubig RR. Pleiotropic phenotype of a genomic knock-in of an RGS-insensitive G184S Gnai2 allele. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6870–6879. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00314-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito DL, Temkin PA, Rogalski SL, Chavkin C. N-terminal tyrosine residues within the potassium channel Kir3 modulate GTPase activity of Galphai. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:32692–32696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204407200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jabourian M, Venance L, Bourgoin S, Ozon S, Pérez S, Godeheu G, Glowinski J, Kemel ML. Functional mu opioid receptors are expressed in cholinergic interneurons of the rat dorsal striatum: territorial specificity and diurnal variation. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;12:3301–3309. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T. Pharmacologic analysis of drug-receptor interactions. 2nd. Raven press; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Sanna PP, Bloom FE. Neuroscience of Addiction. Neuron. 1998;21:467–476. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa T, Jiang X, Hart MJ, Sternweis PM, Singer WD, Gilman AG, Bollag G, Sternweis PC. p115 RhoGEF, a GTPase Activating Protein for Gα12 and Gα13. Science. 1998;280:53643–53652. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KL, Sarvazyan NA, Taussig R, Mackenzie RG, DiBello PR, Dohlman HG, Neubig RR. A point mutation in Galphao and Galphai1 blocks interaction with regulator of G protein signaling proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12794–12797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan KL, Zhong H, Nanamori M, Neubig RR. Rapid kinetics of regulator of G-protein signaling (RGS)-mediated Galphai and Galphao deactivation. Galpha specificity of RGS4 AND RGS7. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33497–33503. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laugwitz KL, Offermanns S, Spicher K, Schultz G. mu and delta opioid receptors differentially couple to G protein subtypes in membranes of human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Neuron. 1993;10:233–242. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90314-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leontiadis LJ, Papakonstantinou MP, Georgoussi Z. Regulator of G protein signaling 4 confers selectivity to specific G proteins to modulate mu- and delta-opioid receptor signaling. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Fando A, Rodriguez-Munoz M, Sanchez-Blazquez P, Garzon J. Expression of neural RGS-R7 and Gb5 proteins in response to acute and chronic morphine. Neuropsychopharm. 1995;30:99–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour A, Fox CA, Burke S, Akil H, Watson SJ. Immunohistochemical localization of the cloned mu opioid receptor in the rat CNS. J Chem Neuroanat. 1995;8:283–305. doi: 10.1016/0891-0618(95)00055-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martemyanov KA, Yoo PJ, Skiba NP, Arshavsky VY. R7BP, a novel neuronal protein interacting with RGS proteins of the R7 family. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5133–5136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Minami M, Satoh M. Up-regulation of RGS4 mRNA by opioid receptor agonists in PC12 cells expressing cloned mu- or kappa-opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;433:29–36. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01485-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nomoto S, Adachi K, Yang LX, Hirata Y, Muraguchi S, Kiuchi K. Distribution of RGS4 mRNA in mouse brain shown by in situ hybridization. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;241:281–287. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papachatzaki MM, Antal Z, Terzi D, Szucs P, Zachariou V, Antal M. RGS9-2 modulates nociceptive behaviour and opioid-mediated synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn. Neurosci Lett. 2011;501:31–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner BA, Gilman AG, Harris BA. Regulators of G protein signaling 6 and 7 Purification of complexes with gbeta5 and assessment of their effects on G protein-mediated signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:31087–31093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.31087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potenza MN, Gold SJ, Roby-Shemkowitz A, Lerner MR, Nestler EJ. Effects of regulators of G protein-signaling proteins on the functional response of the mu-opioid receptor in a melanophore-based assay. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:482–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psifogeorgou K, Terzi D, Papachatzaki MM, Varidaki A, Ferguson D, Gold SJ, Zachariou V. A unique role of RGS9-2 in the striatum as a positive or negative regulator of opiate analgesia. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5617–5624. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4146-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psifogeorgou K, Papakosta P, Russo SJ, Neve RL, Kardassis D, Gold SJ, Zachariou V. RGS9-2 is a negative modulator of mu-opioid receptor function. J Neurochem. 2007;103:617–625. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Z, Schwarz J, Gold SJ, Zachariou V, Wein MN, Choi KH, Kovoor A, Chen CK, DiLeone RJ, Schwarz SC, Selley DE, Sim-Selley LJ, Barrot M, Luedtke RR, Self D, Neve RL, Lester HA, Simon MI, Nestler EJ. RGS9 modulates dopamine signaling in the basal ganglia. Neuron. 2003;38:941–952. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00321-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman DL, Talbot JN, Roof RA, Sunahara RK, Traynor JR, Neubig RR. Identification of small-molecule inhibitors of RGS4 using a high-throughput flow cytometry protein interaction assay. Mol Pharm. 2007;71:169–175. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh O, Murata Y, Odagiri M, Itoh M, Itoh H, Misaka T, Kubo Y. Alternative splicing of RGS8 gene determines inhibitory function of receptor type-specific Gq signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10138–10143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152085999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JH, Waataja JJ, Martemyanov KA. Subcellular targeting of RGS9-2 is controlled by multiple molecular determinants on its membrane anchor, R7BP. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15361–15369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600749200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot JN, Jutkiewicz EM, Graves SM, Clemans CF, Nicol MR, Mortensen RM, Huang X, Neubig RR, Traynor JR. RGS inhibition at G(alpha)i2 selectively potentiates 5-HT1A-mediated antidepressant effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010a;107:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000003107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot JN, Roman DL, Clark MJ, Roof RA, Tesmer JJ, Neubig RR, Traynor JR. Differential modulation of mu-opioid receptor signaling to adenylyl cyclase by regulators of G protein signaling proteins 4 or 8 and 7 in permeabilised C6 cells is Galpha subtype dependent. J Neurochem. 2010b;112:1026–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06519.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesmer JJ, Berman DM, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. Structure of RGS4 bound to AlF4--activated G(i alpha1): stabilization of the transition state for GTP hydrolysis. Cell. 1997;89:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR. G protein coupling and efficacy of mu-opioid agonists: relationship to behavioral efficacy. Revs Anesth. 2004;8:11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Traynor J. Regulator of G protein-signaling proteins and addictive drugs. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1187:341–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Neubig RR. Regulators of G protein signaling and drugs of abuse. Mol Interv. 2005;5:30–41. doi: 10.1124/mi.5.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traynor JR, Terzi D, Caldarone BJ, Zachariou V. RGS9-2: probing an intracellular modulator of behavior as a drug target. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Zastrow M. Regulation of opioid receptors by endocytic membrane traffic: mechanisms and translational implications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;108:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Moriwaki A, Wang JB, Uhl GR, Pickel VP. Ultrastructural immunocytochemical localization of mu-opioid receptors in dendritic targets of dopaminergic terminals in the rat caudate–putamen nucleus. Neuroscience. 1997;81:757–771. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu-Chen LY, Traynor JR. Differential modulation of mu- and delta-opioid receptor agonists by endogenous RGS4 protein in SH-SY5Y cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18357–18367. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Liu M, Mullah B, Siderovski DP, Neubig RR. Receptor-selective effects of endogenous RGS3 and RGS5 to regulate mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24949–24958. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Traynor JR. Opioid-induced down-regulation of RGS4: role of ubiquitination and implications for receptor cross-talk. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:7854–7864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.160911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zeng W, Soyombo AA, Tang W, Ross EM, Barnes AP, Milgram SL, Penninger JM, Allen PB, Greengard P, Muallem S. Spinophilin regulates Ca2+ signalling by binding the N-terminal domain of RGS2 and the third intracellular loop of G-protein-coupled receptors. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:405–411. doi: 10.1038/ncb1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts VJ. Molecular mechanisms for heterologous sensitization of adenylate cyclase. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1–7. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsby PJ, Kellett E, Wilkinson G, Milligan G. Enhanced detection of receptor constitutive activity in the presence of regulators of g protein signaling: applications to the detection and analysis of inverse agonists and low-efficacy partial agonists. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:1211–1221. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.5.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherow DS, Wang Q, Levay K, Cabrera JL, Chen J, Willars GB, Slepak VZ. Complexes of the G protein subunit gbeta 5 with the regulators of G protein signaling RGS7 and RGS9. Characterization in native tissues and in transfected cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24872–24880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Z, Li Z, Guo L, Ye C, Li J, Yu X, Yang H, Wang Y, Chen C, Zhang D, Liu-Chen LY. Regulator of G protein signaling proteins differentially modulate signaling of mu and delta opioid receptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;565:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Zeng W, Popov S, Berman DM, Davignon I, Yu K, Yowe D, Offermanns S, Muallem S, Wilkie TM. RGS proteins determine signaling specificity of Gq-coupled receptors. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3549–3556. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V, Georgescu D, Sanchez N, Rahman Z, DiLeone R, Berton O, Neve RL, Sim-Selley LJ, Selley DE, Gold SJ, Nestler EJ. Essential role for RGS9 in opiate action. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13656–13661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2232594100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariou V, Liu R, LaPlant Q, Xiao G, Renthal W, Chan GC, Storm DR, Aghajanian G, Nestler EJ. Distinct roles of adenylyl cyclases 1 and 8 in opiate dependence: behavioral, electrophysiological, and molecular studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng W, Xu X, Popov S, Mukhopadhyay S, Chidiac P, Swistok J, Danho W, Yagaloff KA, Fisher SL, Ross EM, Muallem S, Wilkie TM. The N-terminal domain of RGS4 confers receptor-selective inhibition of G protein signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:34687–34690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, De Vries L, Gist Farquhar M. Divergence of RGS proteins: evidence for the existence of six mammalian RGS subfamilies. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:411–414. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Neubig RR. Regulator of G protein signaling proteins: novel multifunctional drug targets. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;297:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H, Wade SM, Woolf PJ, Linderman JJ, Traynor JR, Neubig RR. A spatial focusing model for G protein signals. Regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) protien-mediated kinetic scaffolding. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:7278–7284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]