Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the subject-investigator agreement on the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) subsections I and II.

METHODS

Subject-investigator agreement was estimated at baseline and endpoint by Kappa statistics for individual items and concordance correlations for subscale totals using data from two NIH Exploratory Trials in Parkinson’s Disease studies.

RESULTS

All but two questions had moderate subject-investigator agreement at baseline and endpoint. Participants consistently rated their disease activity worse that investigators.

CONCLUSION

UPDRS self-administration produces similar results to investigator-administration. Although slightly elevated, UPDRS self-administration can be accommodated in a clinical trial setting.

Keywords: UPDRS, Parkinson’s disease, Concordance Correlation, Kappa, NET-PD

INTRODUCTION

The clinical utility and consistency of the physician-administered Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) established the UPDRS as a valid and reliable measure of Parkinson’s disease (PD) progression [1–4]. Comparisons of UPDRS-III examinations between trained nurses, neurology residents and movement disorder specialists indicated reliability although nurses and residents consistently gave higher disability scores on the motor exam than the senior movement disorder specialist [5]. Comparisons of responses by physicians and individuals with PD in outpatient clinics on the sections UPDRS-I and UPDRS-II indicate that self-assessment by the individual is a valid and reliable measure of PD activity [6–7].

Clinical trials generally utilize the UPDRS as an outcome measure. Since the administration of the UPDRS by a trained neurologist requires between 9 and 25 minutes [8], large-scale, long-term PD clinical trials could benefit from using participant-reported data to reduce neurologist time and overall trial visit time. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the reproducibility between trial participants and investigators on the UPDRS-I and UPDRS-II subsections using data from two clinical trials.

METHODS

Data from NET-PD Futility Trials

Data from two Phase II futility clinical trials (FS-1 [9] and FS-TOO [10]) conducted by the NIH Exploratory Trials in Parkinson’s Disease (NET-PD) group were used for this analysis. The primary outcome of the FS trials was change in total UPDRS from baseline to twelve-months or the initiation of symptomatic therapy, whichever came first. UPDRS administration was standardized by training all NET-PD investigators using the Movement Disorder Society’s UPDRS Teaching Tape [11–12] prior to study initiation, and by mandating the assessment of each participant by the same investigator throughout the studies. Clinical investigators completed the entire UPDRS, using an interview format with the participant for data collection for Parts I and II. Participants completed the UPDRS-I and UPDRS-II by reading the questions and selecting their best response without interviewer input.

Agreement Analysis

Agreement between investigator and participant responses were assessed at baseline and primary final outcome for both individual items and subsection scores. Any participants with missing data were excluded from the analysis as utilizing any imputation strategy would not add useful information for an agreement analysis.

A Kappa statistic and 95% confidence intervals were estimated for each UPDRS subsection question as a measure of agreement/disagreement beyond chance between the categorical participant and investigator responses [13]. Each UPDRS response is categorized on an increasing scale from 0 to 4, with 0 indicating normal activity or absent symptom and 4 indicating severe disease activity with regards to the symptom in question. Kappa has been shown to be equivalent to an intraclass correlation (ρICC) [14] calculated from a oneway analysis of variance when the number of subjects rated is greater than twenty [13]. As a general rule of thumb [15], kappa > 0.80 denotes excellent agreement beyond chance, 0.40 < kappa ≤ 0.80 moderate agreement, and kappa ≤ 0.40 denotes poor agreement beyond chance.

Response scores were summed for the UPDRS-I and UPDRS-II sections separately; a combined UPDRS-I & II score was also calculated. Agreement for these scores was estimated using the Concordance Correlation Coefficient [16–17] (ρc), which can be expressed as a function of Pearson’s correlation, a measure of reliability, and further accounting for variance differences in the scores. The ρc assesses simultaneously how accurate and precise the investigator’s response is reflected by the participant’s response. The ρc is popular metric for assessing agreement and has been shown to be a more general form of ρICC [17]. The similarity of these agreement measures allows for the interpretation rule of thumb given above for the kappa statistic to be conservatively applied to ρc. All analyses were completed using Stata v11.1 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The FS trials enrolled a total of 413 participants (Table 1). All participants had investigator and self-report UPDRS baseline assessments, with 392 participants completing the endpoint assessment. Demographic and disease activity at baseline were similar between the two FS trials, allowing the agreement analysis to be conducted on the combined dataset.

Table 1.

Demographic and Disease Activity Measures of the NET-PD FS Trial Participants

| FS-1

|

FS-Too

|

Total

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASELINE | N | 200 | 213 | 413 |

| Age (years) | 62.3 (10.4) | 61.0 (10.4) | 61.7 (10.4) | |

| Gender (%) | 126 (63.0%) | 139 (65.3%) | 265 (64.2%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasian (%) | 185 (92.5%) | 191 (90.0%) | 376 (91.0%) | |

| Duration (years) | 0.7 (0.8) | 0.7 (0.9) | 0.7 (0.8) | |

| Education (years) | 15.1 (3.2) | 15.3 (3.2) | 15.2 (3.2) | |

| UPDRS Total | 23.7 (9.5) | 22.3 (8.9) | 23.0 (9.2) | |

| UPDRS-I | 1.3 (1.5) | 1.0 (1.3) | 1.1 (1.4) | |

| UPDRS-I Participant | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.7 (1.6) | |

| UPDRS-II | 6.2 (3.4) | 5.8 (3.1) | 6.0 (3.3) | |

| UPDRS-II Participant | 6.9 (3.8) | 6.4 (3.6) | 6.6 (3.7) | |

| UPDRS-III | 16.2 (7.0) | 15.6 (6.5) | 15.9 (6.7) | |

|

| ||||

| ENDPOINT | UPDRS Total | 27.8 (12.5) | 25.9 (11.1) | 26.8 (11.8) |

| UPDRS-I | 1.5 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.3) | 1.4 (1.5) | |

| UPDRS-I Participant | 1.9 (1.7) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.7 (1.7) | |

| UPDRS-II | 8.0 (4.4) | 7.0 (3.9) | 7.5 (4.1) | |

| UPDRS-II Participant | 8.2 (4.7) | 7.5 (4.4) | 7.8 (4.6) | |

| UPDRS-III | 18.3 (8.7) | 17.7 (7.9) | 18.0 (8.3) | |

All but two of the baseline questions achieved moderate agreement indicated by a 0.40 < kappa ≤ 0.80 (Table 2); no questions achieved an excellent agreement. Questions 2 “Hallucinations” and 14 “Freezing” had poor agreement, while Questions 6 “Salivation”, 9 “Cutting Food”, 10 “Dressing” and 12 “Turning in Bed” had the highest estimated agreement with kappa > 0.60. For the endpoint questions, moderate agreement (0.40 < kappa ≤ 0.80) was also estimated for all but two individual items (Table 2). Questions 2 “Hallucinations” and 17 “Sensory Complaints” had poor agreement and no items achieved excellent agreement. The highest estimated agreement was observed for Questions 6 “Salivation”, 10 “Dressing” and 12 “Turning in Bed” with each having a kappa > 0.60.

Table 2.

Investigator and Participant Scores and Agreement on UPDRS subsections I and II in the NET-PD FS1 and FS-Too Clinical Trials

| # | Question | Baseline

|

Endpoint

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician* | Participant | Agreement† | Physician | Participant | Agreement | ||

| 1 | Memory | 0.31 (0.48) | 0.59 (0.59) | 0.42 (0.35, 0.51) | 0.38 (0.52) | 0.59 (0.62) | 0.40 (0.33, 0.47) |

| 2 | Hallucinations | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.06 (0.31) | 0.16 (0.08, 0.29) | 0.20 (0.45) | 0.09 (0.37) | 0.34 (0.22, 0.51) |

| 3 | Depression | 0.30 (0.55) | 0.43 (0.73) | 0.51 (0.44, 0.59) | 0.32 (0.59) | 0.40 (0.71) | 0.58 (0.48, 0.65) |

| 4 | Motivation | 0.34 (0.59) | 0.58 (0.71) | 0.41 (0.32, 0.48) | 0.46 (0.65) | 0.59 (0.68) | 0.41 (0.34, 0.49) |

| 5 | Speech | 0.45 (0.66) | 0.54 (0.71) | 0.53 (0.48, 0.61) | 0.57 (0.74) | 0.61 (0.75) | 0.54 (0.45, 0.61) |

| 6 | Salivation | 0.48 (0.66) | 0.57 (0.76) | 0.65 (0.59, 0.73) | 0.67 (0.76) | 0.71 (0.78) | 0.60 (0.55, 0.67) |

| 7 | Swallowing | 0.12 (0.36) | 0.21 (0.50) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.59) | 0.17 (0.42) | 0.29 (0.57) | 0.44 (0.35, 0.54) |

| 8 | Writing | 1.13 (0.88) | 1.20 (0.97) | 0.49 (0.44, 0.55) | 1.38 (0.99) | 1.38 (1.07) | 0.51 (0.43, 0.57) |

| 9 | Cutting Food | 0.32 (0.49) | 0.32 (0.49) | 0.62 (0.54, 0.69) | 0.55 (0.66) | 0.51 (0.64) | 0.56 (0.48, 0.63) |

| 10 | Dressing | 0.45 (0.57) | 0.50 (0.62) | 0.62 (0.56, 0.68) | 0.60 (0.63) | 0.65 (0.67) | 0.63 (0.57, 0.70) |

| 11 | Hygeine | 0.31 (0.47) | 0.30 (0.46) | 0.52 (0.43, 0.63) | 0.40 (0.52) | 0.42 (0.51) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.54) |

| 12 | Turning in Bed | 0.35 (0.51) | 0.36 (0.52) | 0.69 (0.62, 0.77) | 0.44 (0.58) | 0.43 (0.57) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.76) |

| 13 | Falling | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.12 (0.37) | 0.43 (0.29, 0.58) | 0.08 (0.34) | 0.15 (0.45) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.66) |

| 14 | Freezing | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.06 (0.27) | 0.15 (-0.01, 0.33) | 0.13 (0.40) | 0.15 (0.45) | 0.59 (0.49, 0.70) |

| 15 | Walking | 0.60 (0.54) | 0.63 (0.57) | 0.48 (0.40, 0.57) | 0.67 (0.57) | 0.67 (0.64) | 0.43 (0.35, 0.51) |

| 16 | Tremor | 1.25 (0.60) | 1.26 (0.67) | 0.53 (0.47, 0.61) | 1.39 (0.65) | 1.34 (0.70) | 0.56 (0.46, 0.61) |

| 17 | Sensory Complaints | 0.44 (0.68) | 0.54 (0.70) | 0.42 (0.33, 0.49) | 0.44 (0.67) | 0.53 (0.70) | 0.35 (0.28, 0.46) |

|

| |||||||

| UPDRS-I | 1.10 (1.37) | 1.67 (1.62) | 0.64 (0.58, 0.69) | 1.35 (1.51) | 1.66 (1.68) | 0.71 (0.66, 0.76) | |

| UPDRS-II | 5.99 (3.26) | 6.62 (3.72) | 0.78 (0.75, 0.82) | 7.49 (4.14) | 7.82 (4.56) | 0.81 (0.78, 0.85) | |

| UPDRS-I & II | 7.09 (3.97) | 8.28 (4.61) | 0.76 (0.72, 0.80) | 8.84 (5.00) | 9.49 (5.60) | 0.81 (0.78, 0.84) | |

Mean (Standard Deviation) reported in Physician and Participant columns.

Kappa (95% Confidence Interval) reported for each item. Concordance Correlation (95% Confidence Interval) reported for subscales.

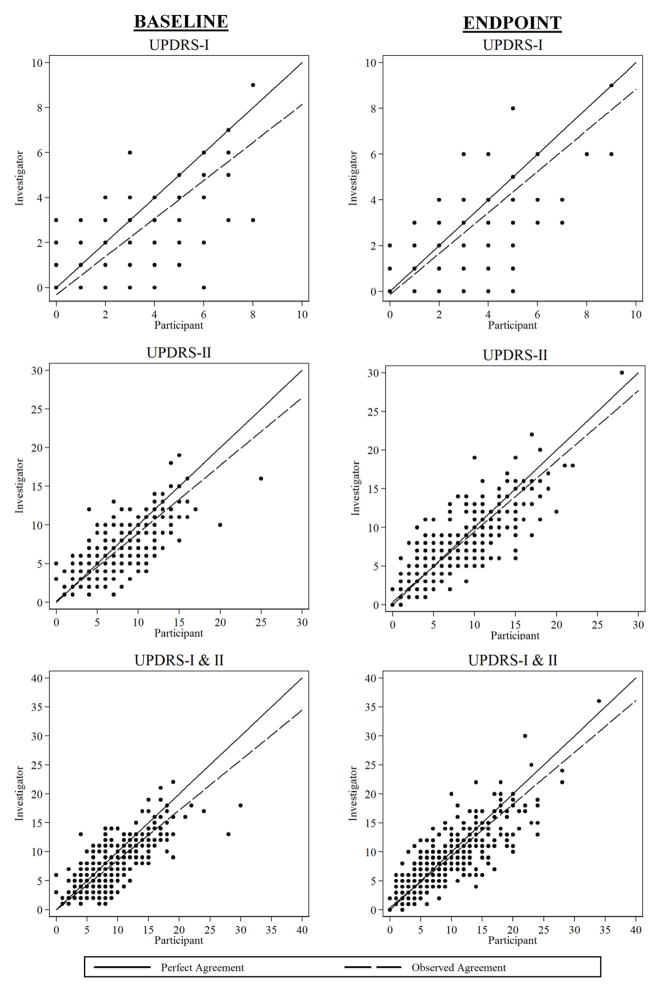

Baseline summary scores were estimated to have moderate agreement by the concordance correlation (Table 2). Slightly higher levels of agreement were estimated for the final outcomes subscores and the combined UPDRS I & II. Agreement plots for each of the UPDRS subscales are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Observed Agreement at Baseline and Final Outcome for UPDRS-I, UPDRS-II and Combined Subscale Total

DISCUSSION

Our data indicate that NET-PD FS participants’ estimates of disease activity as recorded by the individual UPDRS-I and II questions as well as summary scores have moderate agreement to the FS investigators’ responses. Of note, FS participants consistently rated themselves higher (more disease activity) than investigators. While a large number of responses were equal between participant and investigator, participants tended to give a higher disease activity score than investigators when the responses differed. These results confirm previous findings by other studies in PD and other diseases [7, 18–21]. Trained neurologists have been shown to give the lowest UPDRS-II scores when compared to both individuals with PD and their caregivers responses [7] and the lowest UPDRS-III scores when compared to motor exam responses of nurses, neurology residents and a junior movement disorder specialist [5].

Examining the data for those UPDRS questions with poor subject-investigator agreement, several questions suffer from a lack of response variability. For Hallucinations, 19 (4%) of participants’ baseline responses and 24 (6%) of endpoint responses were categorized as abnormal activity (e.g. > 0), while 61 (15%) of baseline and 70 (18%) of endpoint investigator scores categorized Hallucinations as abnormal activity. Conversely, only 7 (2%) of investigators identified Freezing as abnormal activity at baseline compared to 21 (5%) of participants. In these three questions, the limited response variability from either participant or investigator contributed to the estimation of poor agreement. While a large percentage of normal responses were observed, the few abnormal responses contributed to the estimation of low agreement. The design of the FS trials may have contributed to the limited response on these questions as a highly homogenous population of levodopa/dopamine agonist-naïve PD individuals with short-duration was recruited, leaving little likelihood that severe PD symptoms would be assessed.

While endpoint Sensory Complaints agreement was also poor, it was not due to reduced response variability as 168 (43%) participants and 137 (35%) investigators rated abnormal activity for Sensory Complaints. The low agreement estimated may reflect a more subjective nature to the question or the inability to differentiate between “occasional” and “frequent” Sensory Complaints as more overt and objective questions regarding Salivation, Cutting Food, Dressing and Turning in Bed were noted to have the highest agreement at both measurements. Prior investigation into UPDRS agreement found similar differences between individual questions agreement, concluding that low response variability led to poor agreement for Hallucinations and that objectivity led to moderate agreement for Salivation and Dressing [6].

Our study benefited from all study personnel receiving the same educational program for UPDRS administration that included the participant instruction. Over 40 centers in the United States and Canada participated in the trials. Although there was no formal literacy test given, the average education level of participants was 15 years. Further, only native English speakers participated, making our observed differences unlikely explained by literacy or language problems. While these study advantages may limit the generalization of this analysis to the entire PD population seen in general practice, the trial design did allow the rigorous assessment of the self-administered UPDRS in a relatively naïve PD population with potentially subtle changes. It is possible that further experience with the disease itself and use of the UPDRS through multiple clinic visits may improve participant reliability.

A possible limitation of this study is the use of the UPDRS rather than the newer MDS-UPDRS [22–23]. The MDS-UPDRS was not available at the time the study data were collected. The MDS-UPDRS is similar to the UPDRS and but relies on individual-based responses for most non-motor and all motor experiences of daily living. The results of this study suggest that values for MDS-UPDRS items that are comparable to UPDRS items may have moderate agreement with specialist-based ratings with the understanding that the scores may be higher because they are individual-based ratings. More importantly, the NET-PD experience with the participant-administrated UPDRS would indicate that the MDS-UPDRS can be implemented in a large clinical trial setting.

Acknowledgments

Support for Ms. Seidel was received from NINDS T32 HD052274-01. Dr. Swearingen received support from NINDS T32 NS48007-01A1. Drs. Palesch, Goetz and Tilley received funding from NINDS U01NS043127. Dr. Goetz is supported by the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation (PDF) as part of the Rush PDF Parkinson’s Disease Research Center. Dr. Bergmann received funding from NINDS U10-NS053372.

Footnotes

The authors confirm that they have no conflicts of interest related to this research. The views presented in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Food and Drug Administration. No official support or endorsement of this article by the Food and Drug Administration is intended or should be inferred.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ramaker C, Marinus J, Stiggelbout AM, Van Hilten BJ. Systematic evaluation of rating scales for impairment and disability in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2002;17(5):867–76. doi: 10.1002/mds.10248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richards M, Marder K, Cote L, Mayeux R. Interrater reliability of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale motor examination. Mov Disord. 1994;9(1):89–91. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siderowf A, McDermott M, Kieburtz K, Blindauer K, Plumb S, Shoulson I, et al. Test-retest reliability of the Unified Parkinson’s disease Rating Scale in participants with early Parkinson’s disease: Results from a multicenter clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2002;17(4):758–63. doi: 10.1002/mds.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett DA, Shannon KM, Beckett LA, Goetz CG, Wilson RS. Metric properties of nurses’ ratings of parkinsonian signs with a modified Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Neurology. 1997;49(6):1580–7. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.6.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Post B, Merkus MP, de Bie RM, de Haan RJ, Speelman JD. Unified Parkinson’s disease rating scale motor examination: Are ratings of nurses, residents in neurology, and movement disorders specialists interchangeable? Mov Disord. 2005;20(12):1577–84. doi: 10.1002/mds.20640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Louis ED, Lynch T, Marder K, Fahn S. Reliability of participant completion of the historical section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Mov Disord. 1996;11(2):185–92. doi: 10.1002/mds.870110212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-Martín P, Benito-León J, Alonso F, Catalán MJ, Pondal M, Tobías A, et al. Patients’, doctors’, and caregivers’ assessment of disability using the UPDRS-ADL section: are these ratings interchangeable? Mov Disord. 2003;18(9):985–92. doi: 10.1002/mds.10479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-Martín P, Gil-Nagel A, Gracia LM, Gómez JB, Martínez-Sarriés J, Bermejo F. Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale characteristics and structure: The Cooperative Multicentric Group. Mov Disord. 1994;9(1):76–83. doi: 10.1002/mds.870090112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.NINDS NET-PD Investigators. A randomized, double-blind, futility clinical trial of creatine and minocycline in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2006;66(5):664–71. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201252.57661.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NINDS NET-PD Investigators. A randomized clinical trial of coenzyme Q10 and GPI-1485 in early Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2007;68(1):20–8. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250355.28474.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Chmura TA, Fahn S, Klawans HL, Marsden CD. Teaching tape for the motor section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. Mov Disord. 1995;10:263–6. doi: 10.1002/mds.870100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goetz CG, LeWitt PA, Weidenman M. Standardized training tools for the UPDRS activities of daily living scale: newly available teaching program. Mov Disord. 2003;18(12):1455–8. doi: 10.1002/mds.10591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleiss J. The measurement of interrater agreement. In: Fleiss J, editor. Statistical Methods for Rates and Proportions. 2. New York: John Wiley; 1981. pp. 212–36. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86(2):420–8. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin LI. A concordance correlation coefficient to evaluate reproducibility. Biometrics. 1989;45(1):255–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barnhart HX, Haber MJ, Lin LI. An overview on assessing agreement with continuous measurements. J Biopharm Stat. 2007;17:529–69. doi: 10.1080/10543400701376480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McRae C, Diem G, Vo A, O’Brien C, Seeberger L. Reliability of measurements of participant health status: a comparison of physician, patient, and caregiver ratings. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2002;8(3):187–92. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8020(01)00009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grossman SA, Sheidler VR, Swedeen K, Mucenski J, Piantadosi S. Correlation of participant and caregiver ratings of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6(2):53–7. doi: 10.1016/0885-3924(91)90518-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford S, Fallowfield L, Lewis S. Can oncologists detect distress in their out-participants and how satisfied are they with their performance during bad news consultations? Br J Cancer. 1994;70(4):767–70. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yalcin I, Viktrup L. Comparison of physician and participant assessments of incontinence severity and improvement. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(11):1291–5. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goetz CG, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, Poewe W, Sampaio C, Stebbins GT, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Process, format, and clinimetric testing plan. Mov Disord. 2007;22:41–7. doi: 10.1002/mds.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goetz CG, Tilley BC, Shaftman SR, Stebbins GT, Fahn S, Martinez-Martin P, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): Scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;23:2129–70. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]