Abstract

Protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) is a key regulator of the insulin-receptor and leptin-receptor signaling pathways, and it has therefore emerged as a critical anti-type-II-diabetes and anti-obesity drug target. Toward the goal of generating a covalent modulator of PTP1B activity that can be used for investigating its roles in cell signaling and disease progression, we report that the biarsenical probe FlAsH-EDT2 can be used to inhibit PTP1B variants that contain cysteine point mutations in a key catalytic loop of the enzyme. The site-specific cysteine mutations have little effect on the catalytic activity of the enzyme in the absence of FlAsH-EDT2. Upon addition of FlAsH-EDT2, however, the activity of the engineered PTP1B is strongly inhibited, as assayed with either small-molecule or phosphorylated-peptide PTP substrates. We show that the cysteine-rich PTP1B variants can be targeted with the biarsenical probe in either whole-cell lysates or intact cells. Together, our data provide an example of a biarsenical probe controlling the activity of a protein that does not contain the canonical tetra-cysteine biarsenical-labeling sequence CCXXCC. The targeting of “incomplete” cysteine-rich motifs could provide a general means for controlling protein activity by targeting biarsenical compounds to catalytically important loops in conserved protein domains.

INTRODUCTION

Biarsenical probes are small molecules, based on the prototype 4′,5′-bis(1,3,2-dithioarsolan-2-yl)fluorescein (FlAsH-EDT2, Figure 1A), that specifically tag the tetra-cysteine peptide motif CCXXCC through the formation of covalent arsenic-sulfur bonds.1–3 Introduction of a tetra-cysteine motif into any target protein therefore allows for the rapid and specific formation of a covalent protein/small-molecule conjugate for the protein of interest. Although the first biarsenical tags were developed as cell-permeable protein-visualization tools (the FlAsH/tetra-cysteine conjugate is much more fluorescent than the bis-ethanedithiol adduct FlAsH-EDT2),1 subsequent work has demonstrated that biarsenical probes are highly versatile biochemical and biophysical tools3: Biarsenicals can be used to monitor protein folding, conformation, denaturation, and aggregation4–7; as receptors for light-induced protein inactivation8; and even as direct modulators of protein activity.9–11

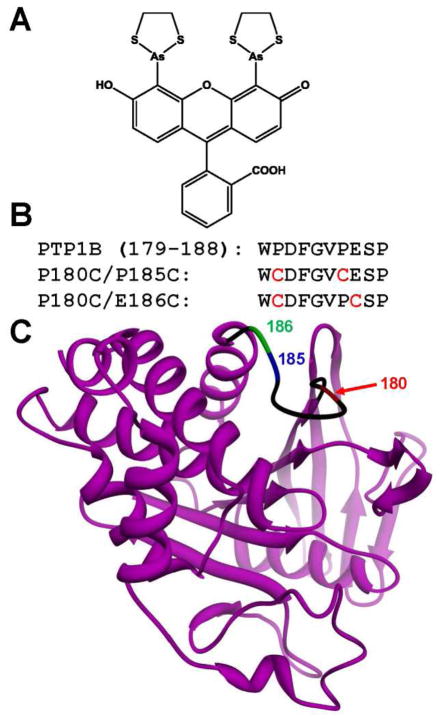

Figure 1.

Design of biarsenical-sensitized mutants of PTP1B. (A) Chemical structure of FlAsH-EDT2. (B) Sequence alignment of the WPD loops (residues 179–188) of wild-type PTP1B, P180C/P185 PTP1B, and P180C/E186C PTP1B. The positions of the site-directed cysteine mutations are highlighted in red. (C) Placement of sensitizing cysteine mutations within the three-dimensional structure of PTP1B. PTP1B is shown as a ribbon, with its WPD loop in the “open” conformation (PDB: 2HNQ).29 The WPD loop is shown in black, with the exception of the positions of the sensitizing mutations introduced in the present study: 180 (red), 185, (blue), and 186 (green).

Our lab has been particularly interested in the latter application of biarsenical chemistry: we have shown that FlAsH-EDT2 can be used to either inhibit11–13 or upregulate14 the activity of engineered protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPs). With regard to PTP inhibition, we have demonstrated that insertion of an optimized tetra-cysteine motif (CCPGCC) in the conserved WPD loop of the catalytic domain of a target PTP is sufficient for “sensitizing” the resulting mutant (PTP-CCPGCC) to inhibition by FlAsH.11 In other words, the PTP-CCPGCC/FlAsH conjugate has much lower PTP activity than the PTP-CCPGCC enzyme in the absence of FlAsH. FlAsH-EDT2 has no significant effect on any naturally occurring PTP assayed to date12; therefore, FlAsH sensitization provides a systematic means for specifically inhibiting a single PTP with a covalently attached small-molecule probe, even in the presence of many homologous enzymes. A key advantage of using protein engineering for targeting PTPs is that successful sensitization approaches may be applicable to many PTPs: the position of the sensitizing CCPGCC insertion is readily identifiable from primary sequence alignments. In principle, then, off-target PTPs can become targets (in separate experiments, targeting different PTP activities) simply by introduction of biarsenical sensitivity into subsequent PTPs that one wishes to study.12 It is likely that targeting of sensitized PTPs will be readily applicable to the systematic delineation of PTP function in whole-cell signaling experiments, as introduction of a gene encoding a sensitized PTP into a cell potentially generates a system in which only a single PTP can be inhibited by a biarsenical ligand.

For some PTP targets, however, a significant limitation of the peptide-insertion approach to sensitization lies in the radical nature of the CCPGCC insertion. For example, the insertion mutant deriving from protein tyrosine phosphatase 1b (PTP1B-CCPGCC) demonstrates drastically reduced activity even in the absence of FlAsH-EDT2: PTP1B-CCPGCC has a 50-fold reduction in the value of kcat, as compared with the naturally occurring PTP1B.12 It is unclear whether this loss of activity results from an inherent deficiency in the catalytic activity in folded PTP1B-CCPGCC protein or a destabilization of the PTP-domain fold that leads to a partially unfolded protein. Regardless, this insertion-induced loss of activity limits the prospects of using PTP1B-CCPGCC as a ligand-sensitive protein target in mammalian cellular studies, as a critical criterion for the biological usefulness of such approaches is that the engineered target can “silently” replace the function of the wild-type.15–17 PTP1B-CCPGCC is thus predicted to be a poor candidate for use in signaling studies; one would predict that it would not reconstitute the function of wild-type PTP1B in the absence of FlAsH-EDT2 due to its intrinsically low activity and/or stability.

The failure to identify a highly active biarsenical-sensitive variant of PTP1B through CCPGCC insertion is particularly vexing because of the biological importance of this phosphatase target. PTP1B it is arguably the most important classical PTP in the biological and pharmaceutical literature due to its key role as a signaling regulator of the insulin- and leptin-response pathways.18–22 Despite intensive PTP1B-inhibitor-discovery efforts, most known PTP1B inhibitory compounds suffer from a lack of target specificity (other classical PTP catalytic domains share a significant degree of sequence and structural homology with PTP1B) and poor bioavailability (at physiological pH, most of the known PTP1B-binding pharmacophores contain negatively charged pTyr mimetics that lower an inhibitor’s cellular permeability). Therefore, chemical tools that are capable of specifically inhibiting PTP1B with high target specificity in a cellular context are still needed.

Here we report that introduction of a minimized biarsenical-binding motif can be used to identify a highly active and biarsenical-sensitive variant of PTP1B. Using a cysteine-rich motif developed on a homologous PTP, we show that two cysteine mutations in a conserved loop of the PTP domain are sufficient to sensitize PTP1B to inhibition by a biarsenical probe in vitro. We also demonstrate that the activity of the resulting biarsenical-sensitized PTP mutant can be successfully targeted in the contexts of whole-cell lysates and intact bacterial cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General

FlAsH-EDT2 was synthesized as described1–2, 11 and dissolved in DMSO. All PTP assays were performed in triplicate; error bars and “±” values represent the standard deviations of at least three independent experiments.

Cloning and Mutagenesis of a PTP1B-Expression Vector

A plasmid for the expression of PTP1B was generated by cloning the gene encoding PTP1B from the plasmid pGEX-KG-PTP1B23 (Zhong-Yin Zhang, Indiana University) into pET-21b. (See Supporting Information for all primer sequences.) A PTP1B-encoding PCR product and pET-21b were doubly digested with EcoRI and SalI, gel purified, and ligated using T4 DNA ligase, yielding pOBD002, which encodes PTP1B with a C-terminal six-histidine tag (PTP1B-His6). Mutations to the PTP1B gene were introduced using the Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Desired mutations were confirmed by sequencing (Cornell Biotechnology Resource Center).

Expression and Purification of Wild-Type and Mutant PTP1B Enzymes

BL21(DE3)-codonPLUS-RIL E. coli (Stratagene) containing the appropriate PTP1B-encoding plasmid were grown overnight at 37°C in LB. Cultures were diluted, grown to mid-log phase (OD600 = 0.5), induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (IPTG), and shaken at 23°C for 14 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in binding buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.8, 500 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole), and lysed by French Press at ~2000 psi. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and enzyme purifications were carried out using SwellGel Nickel Chelated Discs (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein solutions obtained were exchanged into storage buffer (50 mM 3,3-dimethylglutarate pH 7.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT), concentrated, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C. Bradford assays and SDS-PAGE were used to estimate enzyme concentrations.

Phosphatase Activity and Inhibition Assays with pNPP

PTP1B assays using para-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) as substrate were carried out in a total volume of 200 μL, containing PTP buffer (50 mM 3,3-dimethyl glutarate, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0), enzyme (diluted to 20–75 nM in PTP buffer; final DTT concentration: ≤ 2 μM), and pNPP (0.625–10 mM). PTP reactions were quenched by the addition of 40 μL of 5 M NaOH, and the absorbances (405 nm) of 200 μL of the resulting solutions were measured on a VersaMax plate reader (Molecular Devices). Kinetic constants were determined by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using SigmaPlot 11.0. For FlAsH-inhibition experiments, PTP1B samples (100 nM) were incubated with FlAsH-EDT2 concentrations ranging from 62.5 nM to 2 μM, or with DMSO only, for two hours at room temperature. The PTP activities of the solutions were then measured by assaying them with pNPP as described above at a pNPP concentration equal to the previously determined KM of the enzyme.

Phosphatase Activity and Inhibition Assays with Phosphopeptide

PTP1B assays using phosphopeptide as substrate were carried out in a total volume of 140 μL, containing peptide buffer (50 mM 3,3-dimethyl glutarate, 125 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.0), enzyme (diluted to 25–125 nM; final DTT concentration: ≤ 2 μM), and phosphopeptide substrate (100 μM, DADEpYLIPQQG, Calbiochem). Reactions were initiated by the addition of the phosphopeptide after pre-incubation of the enzyme with FlAsH-EDT2 (5×PTP1B concentration). The change in absorbance at 282 nm was measured over time and kinetic constants were determined by fitting the data to the integrated Michaelis-Menten as described previously.24

Fluorescence

Solutions containing wild-type or mutant PTP1B (1 μM) and FlAsH-EDT2 (25 nM) in PTP buffer were incubated at room temperature for two hours. Fluorescence values (excitation: 510 nm, emission: 540 nm, cutoff: 530 nm) of the solutions were measured on a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M5 fluorimeter.

Sensitized PTP1B Inhibition in Cell Lysates and Intact Cells

Lysates

PTP activity of the total lysate from cells expressing the PTP of interest was measured using pNPP (see above). To prepare lysates, 50-mL aliquots of BL21(DE3)-CodonPlus E. coli cells expressing the PTP of interest were removed from larger cultures (see above), pelleted, and stored at −80° C. The pellets were then resuspended in PTP buffer, lysed by French Press, and clarified by centrifugation. Lysates were incubated with FlAsH-EDT2 (concentrations ranging from 0.1–10 μM) or DMSO for 2 hours at room temperature and assayed with pNPP.

Intact bacteria

PTP1B overexpression was carried out in 50-mL cultures essentially as described above, except that cultures were induced with IPTG for 5 hours, after which the cultures were centrifuged for 15 minutes at 4500 rpm. Media was removed and the cell pellets were washed with 20 mL of extracellular buffer25 (ECB: 135 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4). The resuspended cells were then split into two 10-mL portions and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 4500 rpm. The supernatant was removed and the cell pellets were resuspended in 5 mL of ECB containing 5 μM FlAsH-EDT2 or DMSO vehicle and incubated for 4 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. The cells were then washed 3 times, as before, with 10 mL ECB. After the third wash, the cell pellets were resuspended in 5 mL of PTP buffer, lysed by French Press, and clarified by centrifugation. The PTP activities of the lysates (5 μL) were assayed using pNPP as substrate as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Design Strategy

In an attempt to generate biarsenical-sensitized mutants of PTP1B that retain wild-type-like activity and stability in the absence of FlAsH-EDT2, we introduced cysteine point mutations in the enzyme’s WPD loop (Figure. 1B, C).26 The WPD loop is a highly conserved motif of the PTP fold that can alternate between “open” and “closed” conformations.27 The dynamics of the open/closed transition is of key importance for PTP activity, as the WPD loop contains a critical aspartic-acid residue (the “D” of WPD) that can only perform its general-acid/base functions when the loop is in the closed form.28 We have shown previously that, when FlAsH is specifically targeted to an engineered WPD loop, the binding of the small molecule to the WPD loop can alter the kinetics of the open/closed transition and either inhibit11 or activate14 the target PTP’s activity.

Based on homology to a previously sensitized PTP,13, 26 we selected three positions in PTP1B’s WPD loop as potential sensitization sites (Figure 1B, C): proline 180 (P180), proline 185 (P185), and glutamate 186 (E186).29 Mutations at these positions could potentially confer affinity for biarsenical small molecules to PTP1B’s WPD loop without affecting the overall length of the loop or the chemical structure of residues that have previously been shown to be important for PTP1B’s enzyme activity and/or substrate recognition.28, 30–31 Hypothesizing that we would need, at the minimum, two properly spaced cysteine residues to confer a specific interaction with biarsenicals (one thiol to react with each arsenic atom), we generated two potentially biarsenical-sensitized double mutants P180C/P185C and P180C/E186C PTP1B. Six-histidine tagged constructs of both double mutants expressed well from E. coli (~ 20 mg/L of culture) and were readily purified using immobilized metal affinity chromatography. In contrast to the instability and temperature sensitivity that we have observed with the PTP1B-CCPGCC insertion mutant (unpublished observations), the point mutants P180C/P185C and P180C/E186C PTP1B demonstrated no qualitative differences, with respect to wild-type PTP1B or each other, in their benchtop stabilities or resistance to freeze/thaw cycles.

Activities of Biarsenical-Sensitized PTP1B Mutants

To investigate the effects of the cysteine mutations on the inherent activities of P180C/P185C and P180C/E186C PTP1B, we measured the kinetic constants of these enzymes with the general PTP substrate para-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) and compared the values with those derived from the wild-type enzyme (Table 1). Encouragingly, the results indicated that the minimized FlAsH-sensitization strategy could be used to produce a PTP1B mutant that exhibits kinetic characteristics similar in nature to wild-type PTP1B, namely P180C/E186C PTP1B. The 180/186 double mutant exhibits a catalytic rate constant (kcat) that differs from that of wild-type PTP1B by less than a factor of 2 and a catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) that is 25% higher than the wild-type value. In contrast, P180C/P185C PTP1B exhibits a substantially greater defect in catalytic rate constant (7.5-fold lower than that of wild-type), and as a result this mutant was not investigated further.

Table 1.

Kinetic constants for wild-type PTP1B, P180C/P185C PTP1B, and P180C/E186C PTP1B with pNPP as substrate.

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (mM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type PTP1B | 13.36 ± 2.87 | 2.29 ± 0.21 | 5.82 ± 1.13 |

| P180C/P185C PTP1B | 1.77 ± 0.26 | 2.03 ± 0.25 | 0.87 ± 0.14 |

| P180C/E186C PTP1B | 7.12 ± 0.34 | 0.98 ± 0.09 | 7.34 ± 1.08 |

To ensure that P180C/E186C PTP1B retains activity with more physiologically relevant substrates than the small-molecule substrate pNPP, we investigated the mutant’s ability to dephosphorylate the phosphopeptide DADEpYLIPQQG, corresponding to an autophosphorylation site on the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).32 As observed with the pNPP assay, P180C/E186C PTP1B dephosphorylates DADEpYLIPQQG with catalytic rate constants similar to those of wild-type PTP1B (Table 2). P180C/E186C PTP1B exhibits a kcat that is less than 2-fold reduced from that of the wild-type, almost precisely paralleling the result with pNPP (Table 1). Moreover, the Michaelis constant (KM) values of wild-type PTP1B and P180C/E186C PTP1B agree within their associated error of measurement.

Table 2.

Kinetic constants for wild-type PTP1B and P180C/E186C PTP1B with the phosphopeptide DADEpYLIPQQG as substrate.

| Enzyme | kcat (s−1) | KM (μM) | kcat/KM (μM−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| wild-type PTP1B | 15.72 ± 1.67 | 6.47 ± 2.54 | 2.75 ± 1.26 |

| P180C/E186C PTP1B | 8.28 ± 0.84 | 11.92 ± 4.46 | 0.74 ± 0.20 |

Biarsenical Sensitivity of P180C/E186C PTP1B

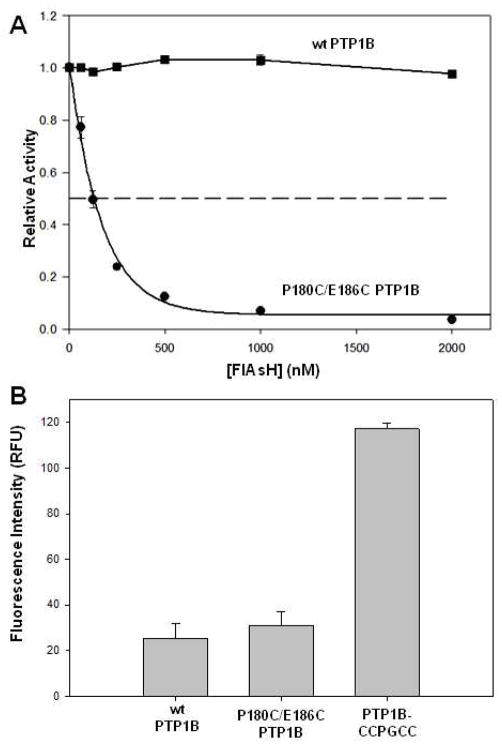

After finding that P180C/E186C PTP1B exhibited wild-type-like PTP activity, we set out to determine whether its minimized FlAsH-binding motif was sufficient to confer novel FlAsH sensitivity. To do so, we pre-incubated wild-type and P180C/E186C PTP1B with a range of FlAsH-EDT2 concentrations (or DMSO vehicle) and measured the activities of the resulting enzymes (Figure 2A). We observed, consistent with earlier findings on other wild-type phosphatases, that the activity of wild-type PTP1B was unaffected by FlAsH-EDT2 up to a concentration of 2 μM. By contrast, the P180C/E186C PTP1B was strongly inhibited by FlAsH-EDT2 in a dose-dependent manner. Under the conditions of the assay (100 nM enzyme), the observed fifty-percent inhibition concentration (IC50) was approximately 130 nM, with maximal inhibition achieved at approximately 1 μM. (Under conditions of such potent, essentially stoichiometric, inhibition, measured IC50 values are highly dependent on the enzyme concentration used, and, therefore, of little fundamental significance. For example, at 100 nM enzyme, it is theoretically impossible that an inhibitor which binds enzyme in a 1:1 manner could demonstrate a 50% inhibition value of less than 50 nM, half the enzyme concentration.) Collectively, the data in Figure 2A show that, indeed, the P180C/E186C double mutation is sufficient to confer strong FlAsH sensitivity into PTP1B.

Figure 2.

FlAsH Sensitivity of P180C/E186C PTP1B. (A) Wild-type (squares) or P180C/E186C PTP1B (circles) was incubated at the indicated FlAsH-EDT2 concentrations and assayed for activity using pNPP as substrate. All activities were normalized to a DMSO-only control for the corresponding enzyme. (B) Fluorescence of FlAsH in the presence of wild-type (wt) PTP1B, P180C/E186C PTP1B, and PTP1B-CCPGCC. The indicated PTP variants (1μM) were incubated with FlAsH-EDT2 (25 nM), and the FlAsH fluorescence of the resulting solutions was measured (excitation: 510 nm, emission: 540 nm).

Because of the lack of fundamental thermodynamic meaning in FlAsH-EDT2’s IC50 value described above, we attempted to achieve a quantitative measurement of the strength of the protein/small-molecule interaction using a more sensitive readout of FlAsH’s binding affinity. FlAsH’s fluorescence intensity increases upon binding to a tetra-cysteine motif1; therefore, fluorescence is a potentially useful tool for determining the strength with which FlAsH binds to target proteins. Indeed, fluorescence has been used by our lab33 and others34 to characterize the strength of protein/biarsenical interactions, and we sought to use this property to measure the binding constant of FlAsH to P180C/E186C PTP1B. We measured the fluorescence of FlAsH-EDT2-treated wild-type PTP1B (negative control), P180C/E186C PTP1B, and, as a positive control for FlAsH fluorescence, a PTP1B mutant that contains a complete tetra-cysteine motif, PTP1B-CCPGCC (Figure 2B).12 As expected, FlAsH’s fluorescence intensity increases significantly upon incubation with PTP1B-CCPGCC. However, we found that the fluorescence of FlAsH in the presence of P180C/E186C PTP1B is not substantially different from that of FlAsH incubated in the presence of wild-type PTP1B. As a result, fluorescence could not be used to estimate a binding constant for the interaction between FlAsH and P180C/E186C PTP1B. Nevertheless, when considered in conjunction with the findings presented in Figure 2A, the data in Figure 2B suggest that FlAsH’s utility in controlling protein activity can be completely decoupled from its more established role in protein visualization, and that the two applications have different target-sequence requirements. P180C/E186C PTP1B provides a second example of our earlier observation that a PTP’s activity can be controlled by a biarsenical with exquisite potency and specificity, even if that PTP does not induce the signature increase in biarsenical fluorescence.14

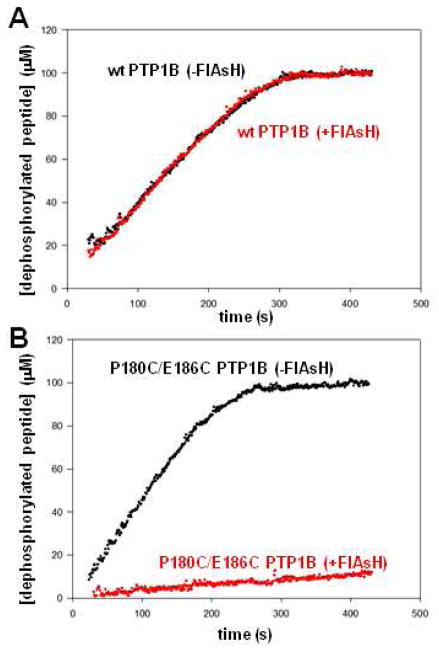

Due to the lack of a direct physical readout of FlAsH’s binding to P180C/E186C PTP1B, we wished to confirm its inhibitory specificity, observed previously with pNPP, in an assay with a different PTP substrate. We therefore investigated the ability of FlAsH-EDT2 to inhibit the dephosphorylation of DADEpYLIPQQG; this phosphopeptide represents a substrate that is more physiologically relevant than pNPP, and an alternate assay could provide assurance that the observed FlAsH inhibition is not an artifact of the colorimetric pNPP assay. We found that, indeed, P180C/E186C PTP1B’s biarsenical sensitivity is substrate independent. Upon pre-incubation with a 5-fold molar excess of FlAsH-EDT2, the inhibition of P180C/E186C PTP1B is essentially complete, as well as completely specific to the mutant (Figure 3). These data are consistent with the results with pNPP (Figure 2A), and taken together, the two in vitro experiments establish that biarsenical targeting of P180C/E186C PTP1B meets the necessary pre-conditions that would be required for its use in a complex cellular environment: FlAsH-induced P180C/E186C PTP1B inhibition is potent, specific, and substrate-independent.

Figure 3.

Target-specific inhibition of P180C/E186C PTP1B using the phosphopeptide DADEpYLIPQQG as substrate. The activities of wild-type PTP1B (A, 25 nM) and P180C/E186C PTP1B (B, 62.5 nM) were measured in the absence (black) or presence (red) of a five-fold molar excess of FlAsH-EDT2. Time-dependent phosphopeptide dephosphorylation was monitored by the increase in absorbance at 282 nm as described previously.24

Targeting of P180C/E186C PTP1B in Cell Lysates and Intact Cells

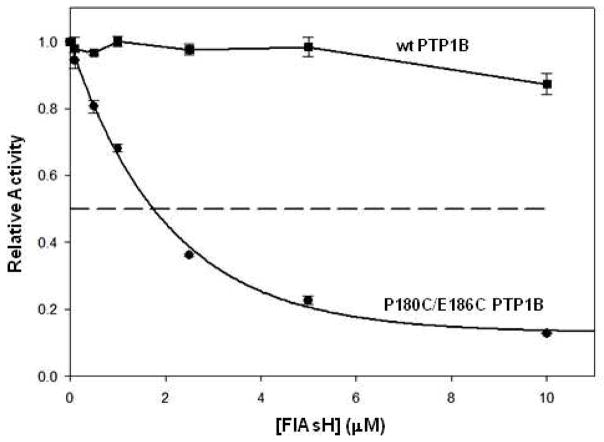

We next investigated whether or not P180C/E186C PTP1B could be targeted by FlAsH in the context of a complex mixture of cellular components. (All of the experiments illustrated in Figures 2 and 3 were performed using purified enzymes.) It has previously been established that naturally occurring proteins that are capable of binding FlAsH do exist,35–36 and it is quite possible that these proteins (as well others that remain to be identified) could compete with P180C/E186C PTP1B for FlAsH binding and thereby interfere with the compound’s specificity and potency. To determine whether P180C/E186C PTP1B’s sensitivity to FlAsH persists in a complex proteomic mixture, we prepared crude lysates of E. coli cell cultures that express either wild-type or P180C/E186C PTP1B and assayed the PTP activities of the lysates after incubation in the presence or absence of FlAsH-EDT2. (Since bacterial genomes do not encode PTPs, total PTP activity in crude lysates from E. coli strains that overexpress exogenous PTPs can be used for a direct readout of specific-PTP activity.) The data in Figure 4 show that FlAsH binding is strong and specific for P180C/E186C PTP1B, even when inhibition occurs in a complex mixture of cellular components. The PTP activity of the lysate containing P180C/E186C PTP1B dropped in a dose-dependent manner, with an apparent IC50 value of approximately 1.75 μM, while the PTP activity of the wild-type PTP1B containing lysate remained unaffected at all FlAsH-EDT2 concentrations tested.

Figure 4.

Target-specific inhibition of P180C/E186C PTP1B in a complex proteomic mixture. Crude cell lysates derived from E. coli that expressed either wild-type PTP1B (squares) or P180C/E186C PTP1B (circles) were incubated at the indicated FlAsH-EDT2 concentrations and assayed for activity using pNPP as a substrate.

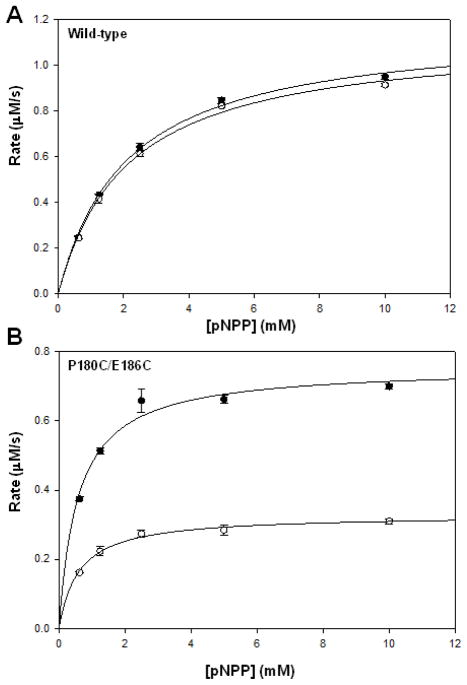

To further investigate FlAsH’s ability to target P180C/E186C PTP1B, we asked whether it could do so in intact E. coli cells. However, the literature precedents concerning the biarsenical cell permeability (or lack thereof) with E. coli, are somewhat mixed.3 Some authors report that bacterial cell walls are refractory to biarsenicals,37 whereas some have presented fluorescence data derived from the use of biarsenicals in living E. coli cells.36 (Perhaps these apparent conflicts arise from differing definitions of “permeable.” Cellular compound concentrations that are sufficient for labeling at the lower limit of fluorescence detection may differ from those needed for full labeling of a target protein.) Our previous investigations have shown that a cycle of freeze-thaw is necessary to “get” FlAsH-EDT2 into cells.33 Nevertheless, we were intrigued by a recent report of strong in vivo FlAsH labeling in E. coli using small amounts of divalent cations in the buffer (2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2),25 and we utilized these conditions for incubations of wild-type and P180C/E186C PTP1B-expressing cells with FlAsH-EDT2. After copiously rinsing away excess FlAsH-EDT2, we lysed the cells and assayed the resulting preparations for PTP activity. We found that the PTP activity derived from wild-type-PTP1B-expressing cells was indistinguishable between DMSO-treated and FlAsH-EDT2-treated samples (Figure 5). Importantly, PTP activity in the lysates from P180C/E186C PTP1B-expressing E. coli was inhibited in the FlAsH-EDT2-treated samples, as compared to the vehicle-treated samples. The degree of inhibition roughly corresponded to an approximately 50% reduction in maximum velocity (Vmax) and was consistent over a range of substrate concentrations investigated (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Target-specific inhibition of P180C/E186C PTP1B in living cells. E. coli cells expressing either wild-type (A) or P180C/E186C PTP1B (B) were incubated in the absence (filled circles) or presence of FlAsH-EDT2 (5 μM, open circles). The cells were pelleted, washed three times, and subsequently lysed. The PTP activity of the lysates was assayed using pNPP at the indicated concentrations.

The reasons for the modest level of inhibition even after prolonged (4 hour) incubation in the presence of FlAsH-EDT2 are not clear. Most likely, given the previously noted complexities associated with biarsenical cell permeability in bacteria, FlAsH-EDT2 is entering the cells only at concentrations much lower than the concentration in the buffer (5 μM). Thus, it is unwise to ascribe physical or quantitative significance to the “IC50” observed in the cellular experiments. Nevertheless, since the two cell populations used in these experiments (wild-type- vs. P180C/E186C-PTP1B expressing) differ only by the identity of two amino-acid side chains in a single protein, the observed differences in inhibition must unambiguously derive from FlAsH binding to its target sequence in the WPD loop of the engineered PTP. These results represent the first demonstration that FlAsH can be used to target PTP1B for inhibition in intact cells for future PTP1B targeting in eukaryotic cells.

More generally, our observation that FlAsH can inhibit a target protein that contains as few as two properly spaced cysteine residues without producing a notable change in fluorescence does present a potentially troubling implication: it suggests that FlAsH may bind to a substantial number of as-yet-unidentified, naturally occurring proteins, and that these hypothetical FlAsH-binding proteins would not be detectable by fluorescence (the standard technique for identifying protein/FlAsH interactions). With regard to using FlAsH-EDT2 to study PTP1B-mediated signaling, however, the key observation is that FlAsH-EDT2 does not inhibit wild-type PTP1B or any wild-type PTP assayed to date.11–13 Although FlAsH-EDT2 (like any small molecule) may have multiple potential binding partners in the cell, for the purposes of controlling PTP activity, our experiments suggest that the compound can possess exquisite selectivity for the engineered PTP1B target over all wild-type PTPs. Since the mammalian-cell permeability of biarsenical reagents is well established,37 it is likely that the biarsenical targeting of P180C/E186C PTP1B can be used to delineate the precise functions of PTP1B in mammalian cell culture.

CONCLUSION

PTP1B is a wide-ranging signaling molecule, with particularly important roles in the insulin-receptor and leptin-receptor signaling pathways. Small molecules that can inhibit cellular PTP1B activity are thus important tools in chemical biology, yet cell-permeable compounds that can target PTP1B with high selectivity over all other PTPs are not known. We have shown that site-directed mutagenesis can be used to generate a double-mutant variant of PTP1B, P180C/E186C-PTP1B, that is sensitive to inhibition by the biarsenical probe FlAsH-EDT2. Upon addition of FlAsH-EDT2, the activity of P180C/E186C-PTP1B is strongly inhibited, even under experimental conditions in which FlAsH and enzyme are present at almost equal concentrations. Importantly, P180C/E186C-PTP1B demonstrates near wild-type activity levels in the absence of FlAsH-EDT2, and FlAsH-EDT2 has no significant effect on PTP activity of wild-type PTP1B. We have also shown that FlAsH can target-specifically inhibit P180C/E186C PTP1B in the context of whole-cell lysates and intact cells. Collectively, our results provide a small-molecule tool that can be used to inhibit PTP1B in complex proteomic mixtures with exquisite selectivity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (2 R15 GM071388-02) and Amherst College.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Sequences of all primers used for cloning and mutagenesis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Griffin BA, Adams SR, Tsien RY. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science. 1998;281:269–272. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams SR, Campbell RE, Gross LA, Martin BR, Walkup GK, Yao Y, Llopis J, Tsien RY. New biarsenical ligands and tetracysteine motifs for protein labeling in vitro and in vivo: synthesis and biological applications. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:6063–6076. doi: 10.1021/ja017687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pomorski A, Krezel A. Exploration of biarsenical chemistry-Challenges in protein research. ChemBioChem. 2011;12:1152–1167. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201100114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Monitoring protein stability and aggregation in vivo by real-time fluorescent labeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:523–528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0304533101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberti MJ, Bertoncini CW, Klement R, Jares-Erijman EA, Jovin TM. Fluorescence imaging of amyloid formation in living cells by a functional, tetracysteine-tagged alpha-synuclein. Nat Methods. 2007;4:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu Y, Su BH, Kim CS, Hernandez M, Rostagno A, Ghiso J, Kim JR. A strategy for designing a peptide probe for detection of beta-amyloid oligomers. ChemBioChem. 2010;11:2409–2418. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheck RA, Schepartz A. Surveying protein structure and function using bis-arsenical small molecules. Acc Chem Res. 2011;44:654–665. doi: 10.1021/ar2001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marek KW, Davis GW. Transgenically encoded protein photoinactivation (FIAsH-FALI): Acute inactivation of synaptotagmin I. Neuron. 2002;36:805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erster O, Eisenstein M, Liscovitch M. Ligand interaction scan: a general method for engineering ligand-sensitive protein alleles. Nat Methods. 2007;4:393–395. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia X, Wang G, Peng Y, Tu MG, Jen J, Fang H. The endogenous CXXC motif governs the cadmium sensitivity of the renal Na+/glucose co-transporter. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:1257–1265. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang XY, Bishop AC. Site-specific incorporation of allosteric-inhibition sites in a protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:3812–3813. doi: 10.1021/ja069098t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang XY, Chen VL, Rosen MS, Blair ER, Lone AM, Bishop AC. Allele-specific inhibition of divergent protein tyrosine phosphatases with a single small molecule. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:8090–8097. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang XY, Bishop AC. Engineered inhibitor sensitivity in the WPD loop of a protein tyrosine phosphatase. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4491–4500. doi: 10.1021/bi800014c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen VL, Bishop AC. Chemical rescue of protein tyrosine phosphatase activity. Chem Comm. 2010;46:637–639. doi: 10.1039/b919815f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop AC, Buzko O, Shokat KM. Magic bullets for protein kinases. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:167–172. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01928-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bishop AC, Zhang XY, Lone AM. Generation of inhibitor-sensitive protein tyrosine phosphatases via active-site mutations. Methods. 2007;42:278–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bishop AC, Ubersax JA, Petsch DT, Matheos DP, Gray NS, Blethrow J, Shimizu E, Tsien JZ, Schultz PG, Rose MD, Wood JL, Morgan DO, Shokat KM. A chemical switch for inhibitor-sensitive alleles of any protein kinase. Nature. 2000;407:395–401. doi: 10.1038/35030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S, Zhang ZY. PTP1B as a drug target: recent developments in PTP1B inhibitor discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12:373–381. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang ZX, Zhang ZY. Targeting PTPs with small molecule inhibitors in cancer treatment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:263–272. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9113-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barr AJ. Protein tyrosine phosphatases as drug targets: strategies and challenges of inhibitor development. Future Med Chem. 2010;2:1563–1576. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blaskovich MA. Drug discovery and protein tyrosine phosphatases. Curr Med Chem. 2009;16:2095–2176. doi: 10.2174/092986709788612693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yip SC, Saha S, Chernoff J. PTP1B: a double agent in metabolism and oncogenesis. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:442–449. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen K, Keng YF, Wu L, Guo XL, Lawrence DS, Zhang ZY. Acquisition of a specific and potent PTP1B inhibitor from a novel combinatorial library and screening procedure. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47311–47319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106568200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang ZY, Maclean D, Thieme-Sefler AM, Roeske RW, Dixon JE. A continuous spectrophotometric and fluorimetric assay for protein tyrosine phosphatase using phosphotyrosine-containing peptides. Anal Biochem. 1993;211:7–15. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang H, He J, Hu F, Zheng C, Yu Z. Detection of Escherichia coli enoyl-ACP reductase using biarsenical-tetracysteine motif. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:1341–1348. doi: 10.1021/bc1001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Andersen JN, Mortensen OH, Peters GH, Drake PG, Iversen LF, Olsen OH, Jansen PG, Andersen HS, Tonks NK, Moller NP. Structural and evolutionary relationships among protein tyrosine phosphatase domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7117–7136. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7117-7136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barr AJ, Ugochukwu E, Lee WH, King ONF, Filippakopoulos P, Alfano I, Savitsky P, Burgess-Brown NA, Muller S, Knapp S. Large-scale structural analysis of the classical human protein tyrosine phosphatome. Cell. 2009;136:352–363. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang ZY. Chemical and mechanistic approaches to the study of protein tyrosine phosphatases. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:385–392. doi: 10.1021/ar020122r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barford D, Flint AJ, Tonks NK. Crystal structure of human protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B. Science. 1994;263:1397–1404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang WQ, Sun JP, Zhang ZY. An overview of the protein tyrosine phosphatase superfamily. Curr Top Med Chem. 2003;3:739–748. doi: 10.2174/1568026033452302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang ZY, Wang Y, Dixon JE. Dissecting the catalytic mechanism of protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1624–1627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang ZY, Thieme-Sefler AM, Maclean D, McNamara DJ, Dobrusin EM, Sawyer TK, Dixon JE. Substrate specificity of the protein tyrosine phosphatases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4446–4450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Walton ZE, Bishop AC. Target-specific control of lymphoid-specific protein tyrosine phosphatase (Lyp) activity. Bioorg Med Chem. 2010;18:4884–4891. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luedtke NW, Dexter RJ, Fried DB, Schepartz A. Surveying polypeptide and protein domain conformation and association with FlAsH and ReAsH. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:779–784. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stroffekova K, Proenza C, Beam KG. The protein-labeling reagent FLASH-EDT2 binds not only to CCXXCC motifs but also non-specifically to endogenous cysteine-rich proteins. Pflugers Arch. 2001;442:859–866. doi: 10.1007/s004240100619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang T, Yan P, Squier TC, Mayer MU. Prospecting the proteome: identification of naturally occurring binding motifs for biarsenical probes. ChemBioChem. 2007;8:1937–1940. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griffin BA, Adams SR, Jones J, Tsien RY. Fluorescent labeling of recombinant proteins in living cells with FlAsH. Meth Enzymol. 2000;327:565–578. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.