Abstract

Caspases are a family of proteases that are involved in the execution of apoptosis and the inflammatory response. A plethora of diseases occur as a result of the dysregulation of apoptosis and inflammation, and caspases have been targeted as a therapeutic strategy to halt the progression of such diseases. Hundreds of peptide and peptidomimetic inhibitors have been designed and tested, but only a few have advanced to clinical trials because of poor drug-like properties and pharmacological constraints. Although much effort has been focused on inhibiting caspases, there are many diseases that result from a decrease in apoptosis, thus activating procaspases could also be a viable therapeutic strategy. To this end, recent efforts have focused on the design of procaspase-3 activators. This review highlights the current progress in the rational design of both specific and pan-caspase inhibitors, as well as procaspase-3 activators.

Keywords: Allosteric activation, allosteric inhibition, caspase inhibitor, drug design, procaspase activator

Introduction

Caspases are an evolutionary conserved family of aspartic acid-directed cysteinyl proteases that have essential functions in apoptosis, inflammation, cell survival, proliferation and differentiation [1,2]. Apoptosis, or controlled cell death, is a fundamental process that allows for cellular homeostasis in multicellular organisms. Dysregulation of apoptosis plays a contributing role in many human diseases; for example, excessive accumulation of aberrant cells with apoptotic deficiency is implicated in both cancer and autoimmune disorders [3]. Conversely, an increase in cell death is associated with heart disease [4,5], stroke [6], neurodegenerative disorders [3] and liver disease [7]. Additionally, abnormal fluctuations in cytokine levels as a result of the inflammatory response have been implicated in several diseases, including osteoarthritis (OA) [8] and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [9], gout [10], inflammatory bowel disorders [11], sepsis [12], and inflammatory skin diseases [13,14]. Targeting the caspases that are responsible for the dysregulation of these processes in diseased cells is a viable strategy to ameliorate disease progression. This review discusses the existing strategies of competitive and allosteric caspase inhibitor design, the advantages and disadvantages associated with targeting caspases with inhibitors, and an emerging strategy to activate procaspases with small molecules as a means to reinitiate cell death in apoptosis-deficient cells.

Caspase inhibitors

The first caspase to be identified was IL-1β-converting enzyme (ICE, later termed caspase-1) in 1993 by Horvitz and colleagues as a human homolog of the Caenorhabditis elegans ced-3 protein, which was determined to be a major regulator of apoptosis [15]. Since the discovery of the founding member of the caspase family, 12 additional members have been identified. Each caspase is classified based on its biological function as either an inflammatory caspase (ie, caspase-1, -4, -5, -11 and -12) or an apoptotic caspase (ie, caspase-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, -9 and -10). All caspases, irrespective of their function, have a similar dimeric 3D structure, leading to a homologous active site region. Caspases cleave their substrates after an aspartic acid residue within a tetrapeptide motif, P4-P3-P2-P1, with cleavage occurring at the peptide bond distal to the P1 residue. Depending on the caspase, residues in positions P2 to P4 can vary; however, there is an absolute requirement for an aspartic acid residue at the P1 position [16]. This requirement is unique to caspases and allows for selectivity over other cysteine proteases. The caspase family is further subdivided into three groups based on their tetrapeptide substrate preference: group I consists of caspase-1, -4 and -5, and recognizes the Trp-Glu-His-Asp (WEHD) motif; group II, consisting of caspase-2, -3 and -7, recognizes the Asp-Glu-Xaa-Asp motif; and group III consists of caspase-6, -8, -9 and -10, which recognize an Iso/Leu/Val-Glu-Xaa-Asp motif [17]. Since the determination of the optimal tetrapeptide recognition sequences for caspase-1 through -9, the study and development of caspase inhibitors has been an active area of research, evaluating both specific and pan-caspase inhibitors.

The design of caspase inhibitors

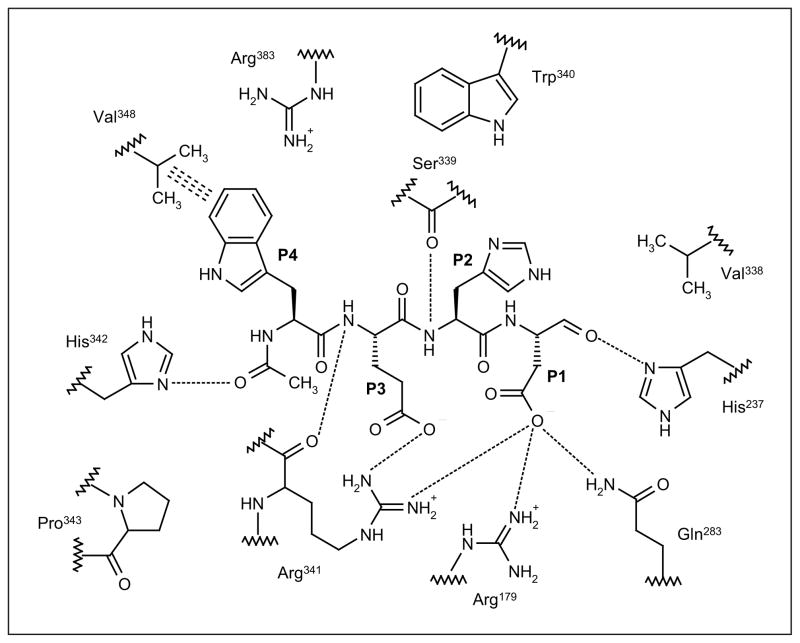

Caspase-1 has been the most extensively studied inflammatory caspase to date, and rivals caspase-3 as the most intensely studied of the caspase family. Additionally, the solving of the crystal structure of caspase-1 [18], and its subsequent co-crystallization with various inhibitors bound in the active site [19], has aided in optimizing both the potency and selective inhibitory capability of caspase-1 inhibitors using structure-based drug design. Since the discovery by Thornberry et al of the optimal peptide recognition sequence for caspase-1 through the design of the reversible inhibitor Ac-WEHD-CHO, which has a Ki of 56 pM [17], caspase inhibitors have progressed from reversible peptide aldehydes to more potent reversible and irreversible inhibitors. Several basic features exist in caspases that allow the design of caspase-1-specific inhibitors based on the composition of the active site residues and the key hydrogen bond interactions with the WEHD tetrapeptide (Figure 1). All caspase-1 inhibitors incorporate an aspartic acid in the P1 site to mimic the cleavage site of the naturally occurring substrate pro-IL-1β. The aspartic acid residue forms key hydrogen bonds with Arg341 and Arg179 to allow the correct orientation of the adjacent electron-deficient atom (or ‘warhead’) to form a covalent bond with the catalytic Cys285 in the S1 site of the enzyme. The S2 site on the enzyme has little hydrogen bond interaction with the P2 residue, making it possible to design pan-caspase inhibitors that bind to multiple caspase active sites. Key hydrophobic interactions between the P3 region and non-polar amino acids in the S3 pocket (Pro343 and Trp340) help to stabilize ligand binding. Finally, the S4 site of the enzyme is large and hydrophobic, and can accommodate a wide range of aromatic functional groups. The S4 pocket is larger in caspase-1 than any other caspase, a feature that has driven the design of caspase-1-specific inhibitors. Hundreds of caspase-1 inhibitors have been designed based on these observations. However, because of pharmacological constraints, tetrapeptide aldehyde inhibitors have poor therapeutic utility based on poor potency, solubility, stability and selectivity [20]; therefore, peptidomimetic inhibitors have been developed by reducing the enzymatically scissile peptide bonds. The re-design of caspase-1 inhibitors was accomplished with constraint of the backbone by using cyclic moieties [21]. Additionally, peptidomimetic inhibitors were truncated to di- or tripeptides by replacing P3 with oxamides, carbamates, indole amides or phenylacetamides [22,23]. Warhead optimization at the P1 position, to determine reversibility and potency using SAR, revealed that fluoromethylketone (FMK), (2,6-dichlorobenzoyl)oxy (DCB) and trifluoperazine (TFP) warheads are successful irreversible moieties [24,25]. Three types of warheads are commonly used for reversible inhibition: aldehyde-based, benzylthiomethyl and aminomethyl ketone warheads [26,27]. Additionally, epoxides and Michael acceptors have also been developed as potent irreversible warheads for caspase inhibitors [28,29]. Based on these design parameters, two caspase-1-specific peptidomimetic inhibitors, pralnacasan (VX-740) and VX-765 (Vertex Pharmaceuticals Inc), entered clinical trials for the treatment of inflammatory diseases; however, the development of both agents for this indication has been discontinued. VX-765 remains in clinical development for the treatment of epilepsy. One pan-caspase inhibitor, emricasan (IDN-655, PF-03491390; Conatus Pharmaceuticals Inc), had entered clinical trials for the treatment of liver disease, but development for this indication has also been discontinued. However, Conatus Pharmaceuticals is developing an intravenous formulation of emricasan to improve liver function following liver transplantation.

Figure 1. The structure of the WEHD tetrapeptide in the active site of capsase-1.

The peptide inhibitor Ac-Trp-Glu-His-Asp-CHO (WEHD; P4 to P1) forms numerous interactions with the active site of caspase-1, including hydrogen bonds (dotted lines) and hydrophobic interactions (triple dashes). This figure was adapted from the crystal structure of inhibitor bound caspase-1 (Protein Data Bank identifier: 1IBC).

Peptidomimetic inhibitors

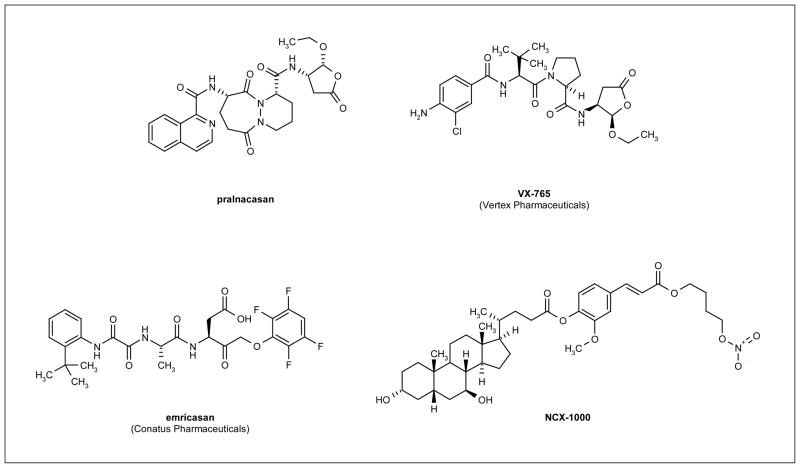

Pralnacasan (Figure 2) is a reversible caspase-1 inhibitor that was being developed for the treatment of a variety of disorders, including RA and OA [30,31]. Preclinical studies demonstrated that the compound inhibited caspase-1 specifically, with an IC50 of 1.3 nM for this caspase compared with micromolar inhibition of the apoptotic caspase-3 and -8 [31]. Pralnacasan was demonstrated to inhibit type II collagen-induced arthritis in mice and to reduce forepaw inflammation by decreasing disease severity by 70% [30]. Phase I clinical trials demonstrated that the drug was well tolerated and had an oral bioavailability of 50% [31]. A phase II trial conducted for 12 weeks in patients (n = 285) with RA demonstrated that pralnacasan was well tolerated and exhibited significant anti-inflammatory effects with no significant adverse side effects, suggesting that pralnacasan is a novel, orally active, anti-RA agent [32]. However, pralnacasan was withdrawn from clinical trials because liver toxicity was observed in long-term animal studies, despite patients enrolled in the trials having no observable side effects after long-term exposure [33].

Figure 2. Structures of promising compounds for caspase inhibition.

Promising lead compounds for caspase inhibition include pralnacasan and VX-765, reversible caspase-1 inhibitors; emricasan, an irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor; and NCX-1000, a nitric oxide-donor caspase inhibitor.

VX-765 (Figure 2) is an orally active, reversible caspase-1 inhibitor that was being developed for the treatment of inflammatory disorders [34]. Preclinical studies revealed that VX-765 is more potent than pralnacasan for inhibition of the inflammatory response, with IC50 values 2-fold lower than those observed for pralnacasan (reviewed in reference [35]). In animal models, VX-765 displayed efficacy in a collagenase-induced arthritis model and a STR/1N spontaneous OA model (reviewed in reference [36]). Phase I clinical trials demonstrated a dose-dependent reduction of cytokine levels in plasma and a phase II trial conducted in patients (n = 68) with psoriasis supported further clinical investigation of VX-765 (reviewed in reference [35]). These data provide promising evidence that VX-765 may be a viable candidate for the treatment of inflammatory diseases. However, no recent development of VX-765 for the treatment of inflammatory disorders has been reported.

Emricasan (Figure 2) is a novel, irreversible, orally active pan-caspase inhibitor that has been investigated for the treatment of chronic HCV infection and liver transplantation rejection. Preclinical studies demonstrated that emricasan ameliorated liver fibrosis by inhibiting hepatocyte apoptosis [37]. In a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial in patients (n = 80) with chronic HCV infection who failed standard therapy or other liver diseases, treatment with emricasan (5 to 200 mg po, qd or bid, or 5 mg po, tid) demonstrated efficacy without severe adverse side effects [38]. Additionally, HCV RNA levels did not increase during the trial, indicating that treatment did not influence viral growth. Emricasan also reduced liver preservation injury following cold ischemia and warm reperfusion during liver transplantation [39]. However, prolonged treatment with emricasan resulted in an increase in neutrophil infiltration into liver allografts [39]; the reasons for this increase have yet to be identified. Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis by treatment with emricasan can promote the inflammatory response, which could trigger caspase-independent cell death. Therefore, the appropriate treatment regimen for maximum efficacy of emricasan on ischemia-reperfusion liver injury will need to be determined. For undisclosed reasons, the oral formulation of emricasan was withdrawn from clinical development [40], highlighting the complexities of advancing a caspase inhibitor through clinical trials.

The examples of peptidomimetic caspase inhibitors highlighted in this section illustrate the difficulty in developing an inhibitor that has promising efficacy in preclinical trials yet withstands the scrutiny of clinical evaluation. Peptidomimetic caspase inhibitors often demonstrate pharmacokinetic liabilities that restrict their utility in vivo. Therapeutic efficacy is limited because of poor cell permeability, marginal activity in intact cells, metabolic instability, toxicity, difficulties with time-dependent inhibition and lack of specificity within the enzyme family. Additionally, the complex structure of many peptidomimetics poses challenges to structural optimization.

Small-molecule caspase inhibitors

Small-molecule caspase inhibitors could be more promising than peptidomimetics to circumvent the aforementioned limitations in therapeutic efficacy. Several strategies have been used during the past decade to develop small-molecule inhibitors of caspases to eliminate the permeability issues associated with the requirement for an aspartic acid in the P1 site. Sulfonamides [24], as well as quinones, epoxyquinones and epoxyquinols [41], and nitric oxide (NO) donors [42] have all demonstrated promising potency and increased permeability as aspartic acid mimics. As a result, one clinical candidate has been identified. As the majority of small-molecule caspase inhibitors are in the early stages of development, little is known regarding the clinical efficacy of such inhibitors. NCX-1000 (Figure 2), a small-molecule inhibitor that selectively inhibits caspase-3, -8 and -9 in the micromolar range, was in phase II clinical trials for the treatment of chronic liver disease [42,43]. NCX-1000 is a steroid-based NO donor that covalently binds to thiol-containing moieties, including the catalytic cysteine of caspases, presumably via S-nitrosylation, thereby causing enzyme inhibition [42]. The results of a phase II, randomized, double-blind, dose-escalating trial in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension revealed that NCX-1000 administration was safe, but did not reduce portal pressure, presumably because of a lack of selective release of NO in the intrahepatic circulation [44]. The development of this compound has since been discontinued.

Allosteric caspase inhibitors

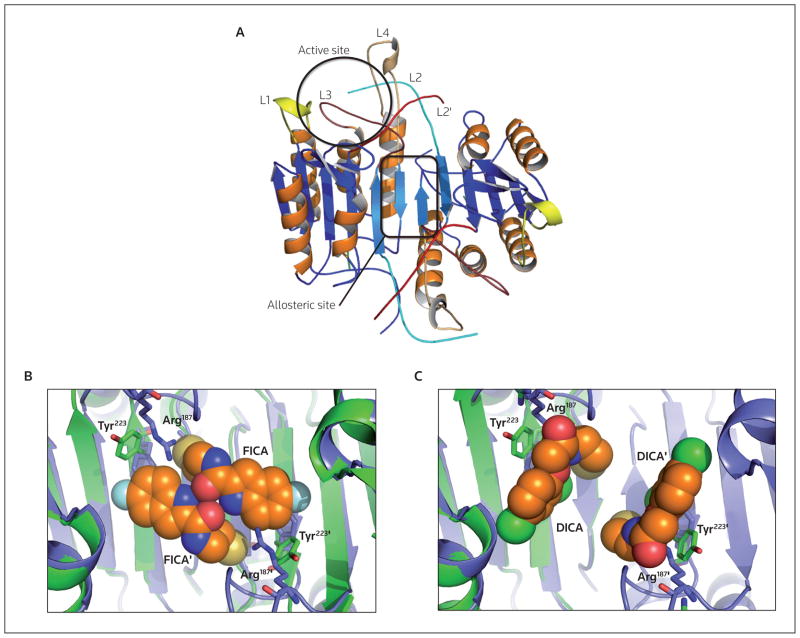

Most potent peptidomimetic and small-molecule inhibitors of caspases are designed to bind the active site region, whether they target the apoptotic or inflammatory enzymes. A newly emerging strategy for targeting an allosteric site in the dimer interface of caspases (Figure 3A) with small-molecule inhibitors will enable the elimination of aspartic acid in inhibitor design strategies and likely establish better drug-like properties. Disulfide trapping, or tethering, experiments have been conducted on caspase-1, -3 and -7 to identify allosteric sites that could be used to inhibit dimer formation [45,46]. Tethering helps to elucidate allosteric binding sites by using a library of small thiol-containing compounds that form disulfide bonds with naturally occurring, solvent-accessible cysteine residues within a protein. Additionally, a residue in a region of interest could be mutated to a cysteine if no native cysteine is present. These tethering experiments identified two classes of compounds that bound to caspase-3 and -7, FICA (5-fluoro-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (2-mercapto-ethyl) amide) and DICA (2-(2,4-dichlorophenoxy-N-(2-mercapto-ethyl)-acetamide) [45]. Both compounds react with Cys264 in caspase-3, which is in close proximity to the dimer interface and 14 Å from the catalytic cysteine. Allosteric inhibitor binding did not cause dissociation of the dimer, but rather prevented binding of the substrate in the active site. Structural data demonstrated that in caspase-7, FICA interacts with Tyr223′ on the opposing monomer to which it binds and therefore occupies the central cavity between the two monomers (Figure 3B); in contrast, DICA interacts with Tyr223 in the same monomer to which it binds (Figure 3C). Regardless of the differences between the binding of FICA and DICA, the same conformational changes occur at the active site. By displacing Tyr223 in the dimer interface, Arg187 in the active site loop (L2; Figure 3A) is pushed out of the central cavity and placed into a position that occludes substrate binding to the active site [45]. The large conformational changes caused by inhibitor binding to the interface result in a conformation that resembles procaspase-7 rather than the active enzyme. Similar data were obtained for caspase-1, in which thienopyrazole bound Cys331 close to the dimer interface, thereby affecting substrate binding [46]. When bound to the allosteric inhibitor, caspase-1 adopted a conformation that closely resembled its ligand-free form. Current models suggest that binding of inhibitors to the dimer interface shifts the equilibrium of species in solution from an active form to an inactive form, making this site a promising allosteric regulator of caspase function. It is conceivable that the binding of an inhibitor to the dimer interface could lead to potent inhibition; however, further chemical optimization will be required, as the binding pocket is quite small, making this approach difficult. Regardless, the data highlight a promising allosteric site in caspases for the design of potent selective inhibitors. No caspase-targeted therapeutic that binds to the dimer interface has been marketed, but tethering could be a viable method for the successful discovery of such compounds.

Figure 3. Structures of the active and allosteric sites of caspases.

(A) The location of the active site of one monomer (black circle) and an allosteric site in the dimer interface (black rectangle) are depicted (Protein Data Bank identifier: 2J30). (B) and (C) The presence of the allosteric inhibitors FICA (Protein Data Bank identifier: 1SHL) and DICA (Protein Data Bank identifier: 1SHJ), respectively, in the dimer interface both result in the same movement of Tyr223 (situated in the dimer interface) that prevents the insertion of Arg187 (situated on the active site loop L2), resulting in a disordered and non-functional active site. In the dimer interface of procaspase-7 (blue protein structure), the intact intersubunit linker causes Tyr223 to point away from the dimer interface compared with the same residue in active caspase-7 (green protein structure).

Caspase activators

Because caspases exist in the cell as inactive zymogens, or proenzymes, they require activation via proteolytic cleavage. The apoptotic caspases can be categorized into two groups based on their proenzyme structure: initiator caspases (caspase-8, -9 and -10) exist as inactive monomers and require dimerization for activation [47,48], while executioner caspases (caspase-3, -6 and -7) exist as inactive dimers that must be processed by proteolytic cleavage of the intersubunit linker for activation [49]. Current chemotherapeutic strategies typically act to promote cellular toxicity and DNA damage, thereby inducing apoptosis indirectly via the activation of caspase-3. Additionally, recent efforts to target the apoptotic machinery as an anticancer strategy have focused on inhibiting key regulatory proteins involved in apoptosis, including the Bcl-2 family members XIAP and Smac/Diablo [50]. A problem with such approaches is that tumorigenic cells can develop resistance because these therapies target proteins that are involved in the early steps of the apoptotic process [51]. Additionally, abnormal levels of several apoptotic proteins in some cancer cells can unexpectedly halt apoptosis, thereby reducing the effectiveness of the therapy because caspase-3 activation is evaded. In contrast, there is a large pool of inactive procaspase-3 in some cancer cells compared with normal cells [52]; thus, targeting procaspase-3 directly, rather than targeting upstream regulators of apoptosis, could lead to a more effective, direct therapy, as caspase-3 is the terminal protease in the apoptotic cascade.

Procaspase conformational states

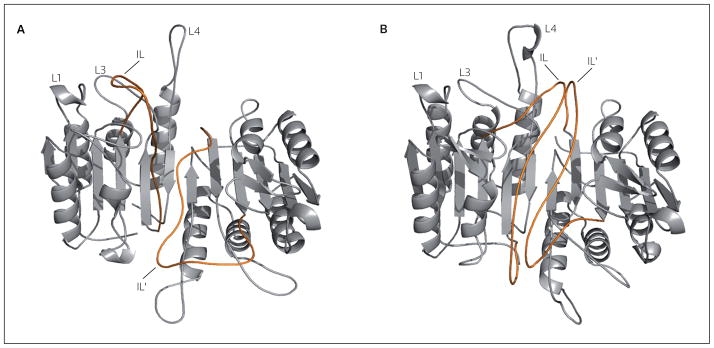

Mutational studies in the dimer interface demonstrated that procaspase-3 fluctuates between two states: the favored state resembles the inactive conformation (Figure 4A), while a second state resembles the active conformation (Figure 4B) [53]. In the inactive conformer, the intersubunit linker that connects the large and small subunits in procaspases occupies the interface; however, in the active form, the intersubunit linker is expelled from the interface, allowing the formation of the substrate binding groove. The active conformer of procaspase-3 was demonstrated to efficiently kill several cancer cell lines and, importantly, was not inhibited efficiently by XIAP, the endogenous inhibitor of caspase-3 [53]. These findings suggest that activation of procaspase-3 can occur even in the absence of cleavage of the intersubunit linker. In principle, a small-molecule drug need only stabilize the active conformer or, conversely, destabilize the inactive conformer, as the two states are in equilibrium. To date, the design of small molecules to inhibit enzyme function has proven to be a far easier task to accomplish than that of enzyme activation. However, the successful design of a small-molecule activator of procaspase-3 may be a better strategy for cancer therapy compared with therapies that target upstream proteins, as drug resistance may be less likely for molecules that target the terminal protease in the pathway.

Figure 4. The structure of executioner procaspase conformations.

The executioner procaspases exist in a strongly favored inactive conformation (A) and an active conformation (B). Interactions between the intersubunit linker (IL; red line) and the dimer interface prevent active site formation. Removal of these loops (Ls) from the dimer interface may be the switch that allows the formation of the fully functional active site. Structures are homology models based on procaspase-7 (A) and caspase-3 (B), as described in reference [53].

Small-molecule caspase activators

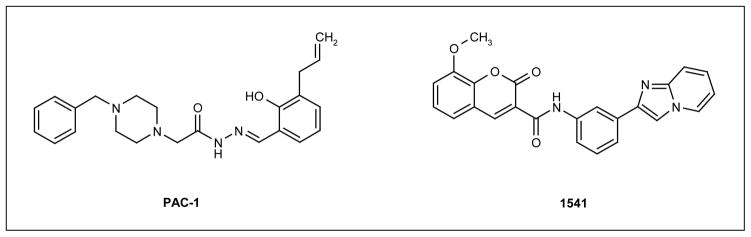

Several approaches have been used to identify small-molecule activators of procaspase-3. A typical approach is the use of HTS of compound libraries. The Hergenrother group used such methods to identify PAC-1 (BioLineRx Ltd; Figure 5), a small molecule that induces both procaspase-3 activation in vitro and apoptosis in several cancer cell lines [52,54]. However, it was unclear how PAC-1 caused procaspase-3 activation in these studies. The activating ability of PAC-1 was questioned in a study by Denault et al that reproduced the experiments by the Hergenrother group, but demonstrated opposing results [55]. Using well-established assays to detect executioner caspase activation, the study by Denault et al demonstrated that PAC-1 and related compounds were not activating executioner caspases directly. Additionally, a study by the Hergenrother group demonstrated that PAC-1 likely acts through limiting zinc-mediated inhibition of procaspase-3 rather than through a direct activation mechanism, and removal of zinc and other divalent metal ions from the buffer greatly reduced the activation effect of PAC-1 on procaspase-3 both in vitro and in cell cultures [54]. Because of this mechanism of non-specific, indirect activation of procaspase-3, it is unlikely that PAC-1 will support a long-term strategy for drug development.

Figure 5. The structures of example small molecules that lead to procaspase-3 activation.

Similar HTS methods were used by Wolan et al to identify small-molecule activators of procaspase-3 [56]. One such compound, 1541 (Figure 5), was demonstrated to activate procaspase-3 with an effective concentration of 2.4 μM. In kinetic and biochemical assays that compared the activity of 1541 with that of granzyme B (a proteolytic procaspase-3 activator), the addition of 1541 resulted in activation of procaspase-3, following a lag phase of approximately 30 min, that corresponded with an increase in the population of cleaved, mature caspase-3. The substitution of residues situated near the active site with alanine identified three residues (Ser198, Thr199 and Ser205), the mutation of which resulted in loss of 1541-induced activation [56]. Based on these findings, it is believed that 1541 activates procaspase-3 through the stabilization of the active state of the proenzyme. This study also tested the effectiveness of this compound at inducing apoptosis in cancer cells. Various cell lines were examined in which cell death was inhibited at different steps in the pathway by a range of mutations. In all cases in which the defect (if present) lay upstream of procaspase-3 activation (eg, a Bak/Bax double-knockout that prevents the release of cytochrome C from the mitochondria), introduction of 1541 led to the recovery of apoptosis [56]. As expected, this effect was not observed in cells deficient in procaspase-3. Overall, the data indicate that procaspase-3 can be activated directly and may provide an exciting new prospect for anticancer therapeutics.

Although research has been undertaken to activate procaspase-3 as a potential therapy, there remains substantial potential for improvement. Although PAC-1 induces procaspase-3 activation in cancer cells, this compound is not a direct activator and therefore might allow the development of resistance. Compound 1541 exhibits significantly greater promise because the evidence strongly supports a direct mechanism for procaspase-3 activation. However, a structure of this small molecule bound to either caspase-3 or procaspase-3 has yet to be obtained. Such a structure would aid in understanding the allosteric mechanism for proenzyme activation and lead to drug optimization using structure-based drug design.

Conclusion

Caspases have tremendous potential in drug discovery, but further research must be conducted to enable clinical efficacy. These proteases are implicated in the progression of a multitude of diseases involved with both defective apoptosis and inflammation. Peptide and peptidomimetic active site inhibitors of caspases are difficult to optimize because of the absolute requirement of aspartic acid in the P1 site, resulting in poor pharmacokinetic profiling and cell permeability, and clinical failure. Hundreds of caspase-specific inhibitors have been designed, but few have progressed to clinical trials for a variety of reasons. This lack of progression further highlights the complexity associated with designing peptidomimetics to target caspases. Non-peptide based, small-molecule inhibitors designed to target both the active site and the allosteric pocket in the dimer interface, are more promising with regard to optimizing pharmacokinetic parameters, specificity and ADME requirements. A new and exciting area of drug design associated with caspases is the identification and rational design of small-molecule activators of procaspase-3 for the treatment of cancer and autoimmune disorders. A major hurdle in this endeavor is the absence of a crystal structure of procaspase-3. In order to optimize lead candidates, a structure would be beneficial to understand the molecular details of the interactions that promote activation.

References

•• of outstanding interest

• of special interest

- 1.Lamkanfi M, Festjens N, Declercq W, Vanden Berghe T, Vandenabeele P. Caspases in cell survival, proliferation and differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14(1):44–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Festjens N, Cornelis S, Lamkanfi M, Vandenabeele P. Caspase-containing complexes in the regulation of cell death and inflammation. Biol Chem. 2006;387(8):1005–1016. doi: 10.1515/BC.2006.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleischer A, Ghadiri A, Dessauge F, Duhamer M, Rebollo MP, Alverez-Franco F, Rebollo A. Modulating apoptosis as a target for effective therapy. Mol Immunol. 2006;43(8):1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narula J, Chandrasekhar Y, Dec G. Apoptosis in heart failure: A tale of heightened expectations, unfulfilled promises and broken hearts…. Apoptosis. 1998;3(5):309–315. doi: 10.1023/a:1009673501809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saraste A, Pulkki K, Kallajoki M, Henriksen K, Parvinen M, Voipio-Pulkki LM. Apoptosis in human acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;95(2):320–323. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linnik MD, Zobrist RH, Hatfield MD. Evidence supporting a role for programmed cell death in focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1993;24(12):2002–2008. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.12.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaeschke M, Gujral JS, Bajt ML. Apoptosis and necrosis in liver disease. Liver Int. 2004;24(2):85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saha N, Moldovan F, Tardif G, Pelletier J-P, Cloutier J-M, Martel-Pelletier J. Interleukin-1β-converting enzyme/caspase-1 in human osteoarthritic tissues: Localization and role in the maturation of interleukin-1β and interleukin-18. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42(8):1577–1587. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1577::AID-ANR3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kay J, Calabrese L. The role of interleukin-1 in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(Suppl 3):iii2–iii9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinon F, Petrilli V, Mayor A, Tardivel A, Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature. 2006;440(7081):237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siegmund B, Lehr H-A, Fantuzzi G, Dinarello CA. IL-1 β-converting enzyme (caspase-1) in intestinal inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(23):13249–13254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231473998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motchkiss RS, Nicholson DW. Apoptosis and caspases regulate death and inflammation in sepsis. Nature Rev Immunol. 2006;6(11):813–822. doi: 10.1038/nri1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antonopoulos C, Cumberbatch M, Dearman RJ, Daniel RJ, Kimber I, Groves RW. Functional caspase-1 is required for Langerhans cell migration and optimal contact sensitization in mice. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3672–3677. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansen C, Moeller K, Kragballe K, Iversen L. The activity of caspase-1 is increased in lesional psoriatic epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(12):2857–2864. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan J, Shaham S, Ledoux S, Ellis H, Horvitz HR. The C. elegans cell death gene ced-3 encodes a protein similar to mammalian interleukin-1β-converting enzyme. Cell. 1993;75(4):641–652. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholson DW, Thornberry NA. Caspases: Killer proteases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22(8):299–306. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17•.Thornberry NA, Rano TA, Peterson EP, Rasper DM, Timkey T, Garcia-Calvo M, Houtzager VM, Nordstrom PA, Roy S, Vaillancourt JP, Chapman KT, et al. A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(29):17907–17911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.29.17907. Identified the individual sequence specificities of the caspase proteins and granzyme B required for peptide chain cleavage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker NP, Talanian RV, Brady KD, Dang LC, Bump NJ, Ferenz CR, Franklin S, Ghayur T, Hackett MC, Hammill LD, Herzog L, et al. Crystal structure of the cysteine protease interleukin-1β-converting enzyme: A (p20/p10)2 homodimer. Cell. 1994;78(2):343–352. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brady KD, Geigel DA, Grinnell C, Lunney E, Talanian RV, Wong WW, Walker NP. A catalytic mechanism for caspase-1 and for bimodal inhibition of caspase-1 by activated aspartic ketones. Bioorg Med Chem. 1999;7(4):621–631. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degterev A, Boyce M, Yuan J. A decade of caspases. Oncogene. 2003;22(53):8543–8567. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Semple G, Ashworth DM, Batt AR, Baxter AJ, Benzies DWM, Elliot LH, Evans DM, Franklin RJ, Hudson P, Jenkins PD, Pitt GR, et al. Peptidomimetic aminomethylene ketone inhibitors of interleukin-1β-converting enzyme (ICE) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8(8):959–964. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00136-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22•.Karanewsky DS, Bai X, Linton SD, Krebs JF, Wu JC, Pham B, Tomaselli KJ. Conformationally constrained inhibitors of caspase-1 (interleukin-1β converting enzyme) and of the human ced-3 homologue caspase-3 (cpp32, apopain) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1998;8(19):2757–2762. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(98)00498-3. Describes the use of peptidomimetic inhibitors as a novel strategy to incorporate specificity in caspase-3 inhibition. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Idun Pharmaceuticals Inc. Karanewsky DS, Linton SD. US-05968927. Tricyclic compounds for the inhibition of the ICE/Ced-3 protease family of enzymes. 1999

- 24.Ullman BR, Aja T, Deckwerth TL, Diaz JL, Herrmann J, Kalish VJ, Karanewsky DS, Meduna SP, Nalley K, Robinson ED, Roggo SP, et al. Structure-activity relationships within a series of caspase inhibitors: Effect of leaving group modifications. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13(20):3623–3626. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00755-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graczyk PP. Caspase inhibitors as anti-inflammatory and antiapoptotic agents. Prog Med Chem. 2002;39:1–72. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6468(08)70068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toulmond S, Tang K, Bureau Y, Ashdown H, Degen S, O’Donnell R, Tarn J, Han Y, Colucci J, Giroux A, Zhu Y, et al. Neuroprotective effects of M826, a reversible caspase-3 inhibitor, in the rat malonate model of Huntington’s disease. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(4):689–697. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han BH, Xu D, Choi J, Han Y, Xanthoudakis S, Roy S, Tarn J, Vaillancourt JP, Colucci J, Siman R, Giroux A, et al. Selective, reversible caspase-3 inhibitor is neuroprotective and reveals distinct pathways of cell death after neonatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(33):30128–30136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James KE, Asgian JL, Li ZZ, Ekici OD, Rubin JR, Mikolajczyk J, Salvesen GS, Powers JC. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of aza-peptide epoxides as selective and potent inhibitors of caspases-1, -3, -6, and -8. J Med Chem. 2004;47(6):1553–1574. doi: 10.1021/jm0305016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ekici OD, Gotz MG, James KE, Li ZZ, Rukamp BJ, Asgian JL, Caffrey CR, Hansell E, Dvorak J, McKerrow JH, Potempa J, et al. Aza-peptide Michael acceptors: A new class of inhibitors specific for caspases and other clan CD cysteine proteases. J Med Chem. 2004;47(8):1889–1892. doi: 10.1021/jm049938j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolphi K, Gerwin N, Verzijl N, van der Kraan P, van den Berg W. Pralnacasan, an inhibitor of interleukin-1β converting enzyme, reduces joint damage in two murine models of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2003;11(10):738–746. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(03)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siegmund B, Zeitz M. Pralnacasan (Vertex Pharmaceuticals) IDrugs. 2003;6(2):154–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pavelka K, Kuba V, Moeller Rasmussen J, Mikkelson K, Tamasi L, Vitek P, Rozman B. Clinical effects of pralnacasan (PRAL), an orally-active interleukin-1β converting enzyme (ICE) inhibitor, in a 285 patient phII trial in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):S241. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer U, Schulze-Osthoff K. Apoptosis-based therapies and drug targets. Cell Death Differ. 2005;12(Suppl 1):942–961. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wannamaker W, Davies R, Namchuk M, Pollard J, Ford P, Ku G, Decker C, Charifson PS, Weber P, Germann UA, Kuida K, et al. (S)-1-((S)-2-{[1-(4-Amino-3-chloro-phenyl)-methanoyl]-amino}-3,3-dimethyl-butanoyl)-pyrrolidine-2-carboxylic acid ((2R,3S)-2-ethoxy-5-oxo-tetrahydro-furan-3-yl)-amide (VX-765), an orally available selective interleukin (IL)-converting enzyme/caspase-1 inhibitor, exhibits potent anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting release of IL-1β and IL-18. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;321(2):509–516. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.111344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eda H. Therapeutic potential for caspase inhibitors present and future. In: O’Brien T, Linton SD, editors. Design of caspase inhibitors as potential clinical agents. CRC Press; Boca Raton, FL, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Braddock M, Quinn A. Targeting IL-1 in inflammatory disease: New opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3(4):330–339. doi: 10.1038/nrd1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37•.Linton SD, Aja T, Armstrong RA, Bai X, Chen L-S, Chen N, Ching B, Contreras P, Diaz J-L, Fisher CD, Fritz LC, et al. First-in-class pan caspase inhibitor developed for the treatment of liver disease. J Med Chem. 2005;48(22):6779–6782. doi: 10.1021/jm050307e. Describes the development of the first irreversible pan-caspase inhibitor to enter clinical trials. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pockros P, Schiff E, Shiffman M, McHutchison J, Gish R, Afdhal N, Makhviladze M, Huyghe M, Hecht D, Oltersdorf T, Shapiro D. Oral IDN-6556, an antiapoptotic caspase inhibitor, may lower aminotransferase activity in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46(2):324–329. doi: 10.1002/hep.21664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baskin-Bey E, Washburn K, Feng S, Oltersdorf T, Shapiro D, Huyghe M, Burgart L, Garrity-Park M, van Vilsteren F, Oliver L, Rosen C, et al. Clinical trial of the pan-caspase inhibitor, IDN-6556, in human preservation injury. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(1):218–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfizer pipeline. Pfizer Inc; New York, NY, USA: 2008. media.pfizer.com/files/research/pipeline/2008_0228/pipeline_2008_0228.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graczyk PP. Caspase inhibitors – A chemist’s perspective. Restor Neurol Neurosci. 1999;14(1):1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fiorucci S, Antonelli E, Tocchetti P, Morelli A. Treatment of portal hypertension with NCX-1000, a liver-specific NO donor. A review of its current status. Cardiovasc Drug Rev. 2004;22(2):135–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3466.2004.tb00136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiorucci S, Mencarelli A, Palazzetti B, Del Soldato P, Morelli A, Ignarro LJ. An NO derivative of ursodeoxycholic acid protects against Fas-mediated liver injury by inhibiting caspase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(5):2652–2657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041603898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berzigotti A, Bellot P, De Gottardi A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Gagnon C, Spenard J, Bosch J. NCX-1000, a nitric oxide-releasing derivative of UDCA, does not decrease portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis: Results of a randomized, double-blind, dose escalating study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(5):1094–1101. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45••.Hardy JA, Lam J, Nguyen JT, O’Brien T, Wells JA. Discovery of an allosteric site in the caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(34):12461–12466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404781101. Identified an allosteric binding site in the dimer interface of caspases. Alternative binding sites may be critical for the identification of new compounds that bypass traditional mechanisms for drug resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scheer JM, Romanowski MJ, Wells JA. A common allosteric site and mechanism in caspases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(20):7595–7600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602571103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Muzio M, Stockwell BR, Stennicke HR, Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. An induced proximity model for caspase-8 activation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(5):2926–2930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pop C, Timmer J, Sperandio S, Salvesen GS. The apoptosome activated caspase-9 by dimerization. Mol Cell. 2006;22(2):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.MacKenzie SM, Clark AC. Targeting cell death in tumors by activating caspases. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8(2):98–109. doi: 10.2174/156800908783769391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan T-T, White E. Therapeutic targeting of death pathways in cancer: Mechanisms for activating cell death in cancer cells. In: Khosravi-Far R, White E, editors. Programmed cell death in cancer progression and therapy. Springer Science; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2008. pp. 81–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fulda S. Tumor resistance to apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(3):511–515. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Putt KS, Chen GW, Pearson JM, Sandhorst JS, Hoagland MS, Kwon J-T, Hwang S-K, Jin H, Churchwell MI, Cho M-H, Doerge DR, et al. Small-molecule activation of procaspase-3 to caspase-3 as a personalized anticancer strategy. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nchembio814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53••.Walters JA, Pop C, Scott FL, Drag M, Swartz P, Mattos C, Salvesen GS, Clark AC. A constitutively active and uninhibitable caspase-3 zymogen efficiently induces apoptosis. Biochem J. 2009;424(3):335–345. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090825. Identified a novel allosteric mechanism for the activation of procaspase-3 in a manner that bypasses the normal cellular regulatory pathways. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peterson Q, Goode D, West D, Ramsey K, Lee J, Hergenrother PJ. PAC-1 activates procaspase-3 in vitro through relief of zinc-mediated inhibition. J Mol Biol. 2009;388(1):144–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Denault J, Drag M, Salvesen GS, Alves J, Heidt A, Deveraux QL, Harris J. Small molecules not direct activators of caspases. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3(9):519. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0907-519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56••.Wolan DW, Zorn JA, Gray DC, Wells JA. Small-molecule activators of a proenzyme. Science. 2009;326(5954):853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1177585. Describes the first direct small-molecule activator of procaspase-3 and proposes a possible mechanism for proenzyme activation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]