Abstract

Previously we have shown that microRNA miR-382 can facilitate loss of renal epithelial characteristics in cultured cells. This study examined the in vivo role of miR-382 in the development of renal interstitial fibrosis in a mouse model. Unilateral ureteral obstruction was used to induce renal interstitial fibrosis in mice. With 3 days of unilateral ureteral obstruction, expression of miR-382 in the obstructed kidney was increased severalfold compared with sham-operated controls. Intravenous delivery of locked nucleic acid-modified anti-miR-382 blocked the increase in miR-382 expression and significantly reduced inner medullary fibrosis. Expression of predicted miR-382 target kallikrein 5, a proteolytic enzyme capable of degrading several extracellular matrix proteins, was reduced with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Anti-miR-382 treatment prevented the reduction of kallikrein 5 in the inner medulla. Furthermore, the protective effect of the anti-miR-382 treatment against fibrosis was abolished by renal knockdown of kallikrein 5. Targeting of kallikrein 5 by miR-382 was confirmed by 3′-untranslated region luciferase assay. These data support a completely novel mechanism in which miR-382 targets kallikrein 5 and contributes to the development of renal inner medullary interstitial fibrosis. The study provided the first demonstration of an in vivo functional role of miR-382 in any species and any organ system.

Keywords: microRNA, kidney, unilateral ureteral obstruction

microRNAs (miRNA or miR) are endogenous, dynamic regulators of gene expression. These small oligonucleotides (18–22 nucleotides) regulate target protein expression primarily by binding to the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of mRNA, resulting in translational suppression or degradation of mRNA (1, 8, 10, 18). An miRNA can alter expression of multiple mRNA transcripts through incomplete complementarity allowing them to regulate multiple targets. Several specific miRNAs have been reported to play a significant role in diseases including those involving the cardiovascular system and renal glomerular cells (3, 16, 31).

The development of interstitial fibrosis is a phenotype common to chronic renal injury in humans and animal models (22, 36). It results from an excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins in the tubulointerstitial compartment of the kidney. The cellular mechanisms that regulate this process are of great interest because it has been known for some time that the amount of interstitial fibrosis is a strong indicator of progression of chronic kidney disease (13, 32). A widely used animal model of rapidly developing tubulointerstitial fibrosis is unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). In the obstructed kidney, increases in transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) and other profibrotic signaling molecules stimulate fibrosis through proliferation of renal fibroblasts, recruitment of bone marrow-derived cells, epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT), and possibly other mechanisms (15, 23, 30). With the initiation of profibrotic signaling the delicate balance of extracellular matrix protein synthesis and degradation is disrupted to favor accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins. Significant renal interstitial fibrosis develops in only a matter of days, making UUO a useful model for understanding the different cellular mechanisms contributing to renal interstitial fibrosis.

The in vivo functional role of miRNAs in the development of renal interstitial fibrosis remains unknown with the exception of miR-29b, which we recently showed to suppress several extracellular matrix genes in the rat kidney in vivo (24). In vivo expression analysis and functional studies in cultured cells suggest that miR-192 might also be involved in the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis (5, 19).

We recently discovered miR-382 as a contributor to TGF-β1-induced loss of epithelial characteristics in cultured human renal epithelial cells, a process potentially relevant to renal interstitial fibrosis (17). miR-382 is a poorly understood miRNA and has not been reported to play any role in any disease process in vivo. We hypothesized that miR-382 might play an important role in the development of renal interstitial fibrosis. We utilized the UUO model and combined that with in vivo suppression of miR-382 with intravenous delivery of locked nucleic acid (LNA) -modified anti-miR-382, as well as siRNA-mediated renal knockdown of a miR-382 target gene. With this approach we were able to determine the impact of miR-382 on regional interstitial fibrosis and identify kallikrein 5 (KLK5) as a miR-382 target whose suppression can facilitate the development of interstitial fibrosis in the inner medulla.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

UUO Surgeries

All protocols were approved by the Medical College of Wisconsin institutional animal care and use committee. Mice used in this study were housed on 14 h light-10 h dark cycle and given food and water ad libitum. Male CD-1 mice (20–30 g) underwent UUO or sham operation of the left ureter. The obstruction was produced by ligation of the left ureter following midline laparotomy. The left ureter was isolated, but not ligated in sham operated controls.

Anti-miR-382 Delivery

The effect of miR-382 blockade was tested in mice that underwent 3 days of UUO or in sham-operated controls. LNA-modified anti-scrambled or anti-miR-382 oligonucleotides (Exiqon) were diluted in saline (5 mg/ml) and delivered by tail vein (10 mg/kg) less than 30 min prior to UUO or sham surgery (n = 8–10 for each of the four groups). To ensure continued blockade of miR-382 in 3 day UUO animals an additional injection of the anti-scrambled or anti-miR-382 was given 24 h after surgery. This treatment course was also followed to measure organ-specific miR-382 expression and knockdown in mice that did not undergo surgery.

Local Delivery of siRNA to Obstructed Mouse Kidneys

Stealth in vivo small interfering RNA (siRNA) designed against KLK5 or negative control siRNA (Invitrogen) was combined with in vivo-jetPEI (PolyPlus, New York, NY) at an N/P ratio of 8 per manufacturer's instructions. Following occlusion of the ureter, 10 μg of siRNA was delivered to the kidney by retrograde injection into the ureter proximal to the ligature (20, 25).

Tissue Collection

Kidney tissues were collected at 1, 3, or 7 days after surgery. Kidneys were sectioned axially midkidney. One-half of each kidney was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for total RNA analysis, while the remaining half was fixed in 10% formalin, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned for trichrome staining, immunohistochemistry, or in situ hybridization (ISH). Kidney, liver, left ventricle, and cerebral cortex tissues for miR-382 expression analysis were isolated and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen 3 days after initial anti-miR-treatment.

Real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR measurement of miR-382 was made using a TaqMan miRNA assay (Applied Biosystems), as previously described (17, 24, 33). Expression of 5s rRNA was used to normalize miRNA expression. Real-time PCR was performed on mRNA using SYBR Green chemistry, as previously described (17, 33). 18s rRNA expression was measured to normalize expression levels. Primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primers used in real-time PCR

| Target | Gene Symbol | Sense Primer Sequence 5′→3′ | Anti-sense Primer Sequence 5′→3′ |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Smooth muscle actin | Acta2 | cagcaaacaggaatacgacgaa | gaggcgctgatccacaaaac |

| E-cadherin | Cdh1 | tccacctccagagaactcatttaca | cagacacatagccgaacaaggaa |

| Heat shock-related 70 kDa protein 2 | Hspa2 | caggtggaatataaaggggagatg | ttgaaataggcaggaacagtgatc |

| Matrix metalloproteinase 16 | Mmp16 | tggcgagtgagaaacaacagg | gccccgccagaactaagtaat |

| Protocadherin 7 | Pcdh7 | cataccccactcacccaggata | caaccaccccaatgacaatactaa |

| Kallikrein 5 | Klk5 | gccttgtgtcctggggtgattt | gttccgtggttcctggtgtgg |

| Kallikrein 15 | Klk15 | atggcgacaaggtgctagaggcgaggag | tggcagtgggcggcagtcaaca |

Identification of Predicted miRNA Target Pairs

miR-382 targets were identified using sequence based algorithms available through Targetscan v5.1 (http://www.targetscan.org/) and MicroCosm Targets v5 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm/htdocs/targets/v5/). A literature search was performed to identify predicted miR-382 targets that might be related to extracellular matrix proteins or the development of fibrosis.

Histological Analysis

Imaging.

Kidney tissue was photographed in four radial paths from the cortex to the inner medulla with a SPOT Insight digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments) at ×20 magnification.

Fibrosis.

Trichrome staining was completed on 3 μm thick formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections. The area of extracellular matrix protein containing tissue (blue) was quantified using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices) and expressed as a percentage of total tissue area.

miR-382 ISH

ISH was completed on 5 μm thick FFPE kidney sections using 40 nM single 3′-digoxigenin-labeled probes for miR-382, scrambled control (negative control), or U6 (positive control) from Exiqon. The ISH protocol developed by Dr. W. Kloosterman for Exiqon and for FFPE sections was used with minor modifications (contact Exiqon for original protocol at http://www.exiqon.com). Tissue sections (5 μm) were cleared in xylenes and rehydrated using an ethanol gradient. Sections were treated with diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC) for 1 min, rinsed in DEPC-treated PBS, and then exposed to a 5 min proteinase K (20 mg/ml) treatment at 37°C. Slides were rinsed in DEPC-treated PBS twice and then treated with 0.2% glycine for 30 s and rinsed twice again. The tissues were fixed in freshly made 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by 5 × 5 min rinses in PBS with 0.02% Tween-20 (PBS-T). The tissues were covered with 50 μl of hybridization buffer [50% formamide, 5× SSC, 0.1% Tween, 9.2 mM citric acid (to adjust solution to pH 6), 50 μg/ml heparin, 500 μg/ml yeast RNA] followed by RNase-free hybrislips (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and placed in a humidified hybridization oven for a 2 h prehybridization at 54°C. The probe was diluted in hybridization buffer (40 μM, 75 μl/tissue section) and preheated at 65°C for 5 min to linearize. The probe was then added to the slides, the coverslips were replaced, and the slides were incubated overnight at 54°C. Slides were rinsed 3 × 30 min in 50% deionized formamide/50% 2× SSC, followed by 5 × 5 min PBS-T washes and then blocked for 1 h (2% horse serum, 2 mg/ml BSA in PBS-T at room temperature) followed by overnight incubation at 4°C with 1:100 anti-digoxigenin alkaline phosphatase (AP) antibody in blocking solution. The following day slides were washed 7 × 5 min with PBS-T and 3 × 5 min with AP buffer (100 mM Tris·HCl pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20). Slides were incubated in nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche) diluted in AP buffer for 4 h and then rinsed with double-distilled H2O, to stop the color development, prior to dehydration, clearing, and mounting. The tissue was photographed as described above, and stained regions of the images were thresholded using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). The average integrated optical density was used to quantify miR-382 expression. An average value was calculated for each mouse. Data are reported as percentages of average expression in sham + anti-scrambled-treated mice.

KLK5 Immunohistochemisty

Expression of KLK5 was measured by immunohistochemistry on 3 μm tissue sections using a KLK5 primary antibody (Abcam). The specificity of the antibody was confirmed by Western blot (data not shown). Cleared and rehydrated tissue sections were treated with avidin and biotin (Vector Labs) and blocked in 10% horse serum (Vector Labs) in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 20 (TBS-T) for 1 h. Tissues were incubated with a 1:100 dilution of primary antibody for KLK5 (Abcam #ab60173) in 2% horse serum in PBS-T for 1 h (50% methanol-50% 3% hydrogen peroxide) and rinsed 3 × 5 min in PBS-T. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked during a 30 min treatment with followed by 3 × 5 min PBS-T rinses. The secondary antibody (Biotinylated Anti-goat IgG, Vector Labs) was diluted 1:100 in 2% horse serum in PBS-T for 1 h and rinsed 3 × 5 min in PBS-T. Tissues were treated with ABC (Vector Labs), rinsed, and incubated in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine solution (Vector Labs) for 3 min. Tissues were dehydrated through ethanol gradient, cleared in xylenes, and mounted with Permount (Fisher Scientific). Human tissues underwent an antigen retrieval step with sodium citrate buffer (10 mM sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) at 100°C for 30 min prior to incubation with primary antibody.

In mouse tissues all regions of the kidney stained positive for KLK5. A staining threshold was chosen to quantify the optical density of darkly stained tissue. To more accurately weight the intensity of KLK5-positive tissue in the context of the entire tissue section the total optical density of thresholded tissue was normalized by the fraction of stained tissue to total tissue area as follows: normalized KLK5 expression = total optical density/(thresholded area/total area). An average value was calculated for each mouse, and data were expressed as average percentages of sham + anti-scrambled control.

3′-UTR Analysis

A segment of the 3′-UTR region of the mouse KLK5 mRNA (nucleotides 31–275) including the predicted miR-382 binding site (65–86) was amplified (forward primer, 5′-tcgaactagtccacccaacggcaatgagg-3′; reverse primer, 5′-ttcgaaagctt ctgggtgacggctgaagaaaag-3′) for cloning into pMIR-REPORT luciferase plasmid (Ambion) downstream of the luciferase reporter gene, as described previously (17, 24). An inversion mutation was introduced to the seed region of the 3′-UTR (see Fig. 3C) to test miR-382 binding in the seed regions. The constructs were transfected into HeLa cells cultured in a microplate. Luciferase and β-galactosidase (internal normalizer) activity was measured after treatments with anti-miR-382 and pre-miR-382 as well as negative control oligonucleotides (Exiqon) using the Dual-Light system (ABI).

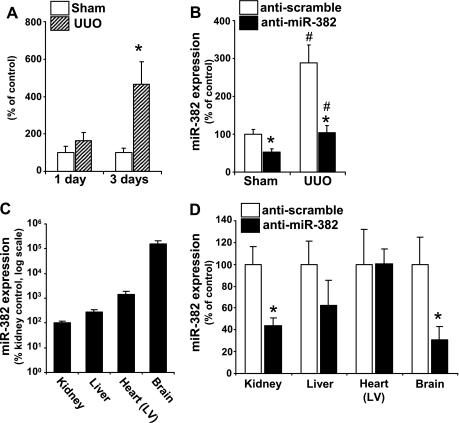

Fig. 3.

Kallikrein 5 (KLK5) was targeted by miR-382. A: miR-382 knockdown did not have significant effects on epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers E-cadherin or α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) expression. Anti-scramble-treated n = 10/group, anti-miR-382 n = 8/group. #P < 0.05 vs. sham-operated animals receiving the same anti-miR treatment. B: the mRNA expression of several predicted miR-382 targets implicated in extracellular matrix remodeling. KLK5 expression was significantly increased when miR-382 was knocked down in sham-operated animals. *P < 0.05 vs. anti-scrambled treated mice with same surgery (P < 0.05). C: MicroCosm-predicted binding site within the 3'-untranslated region (UTR) of mouse KLK5. The seed region is boldfaced and underlined, with wobble pairs represented by curved lines. 3′-UTR reporter analysis confirmed an interaction between miR-382 and the 3′-UTR of KLK5. This interaction did not occur when a point mutation was introduced to the seed region binding sequence by inversion of the “AC” nucleotides (framed by box). n = 4–8 for anti-miR-treatment; n = 10–12 for pre-miR-treatment. *P < 0.05 vs. control oligonucleotides.

Statistics

A Student's t-test or multiple-group analysis of variance was used to make comparisons between all groups unless otherwise indicated. Data are expressed as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Expression of miR-382 was Augmented with 3 Days of UUO in Mice

To determine the effect of UUO on miR-382 expression, miR-382 was measured in the kidneys of mice that had undergone 1, 3, and 7 days of UUO. We found that miR-382 was significantly increased by severalfold after 3 days of UUO (Fig. 1A). miR-382 remained upregulated to a similar extent after 7 days of UUO (data not shown). Subsequent studies were performed at the 3 day time point to focus on the early stage of the development of interstitial fibrosis.

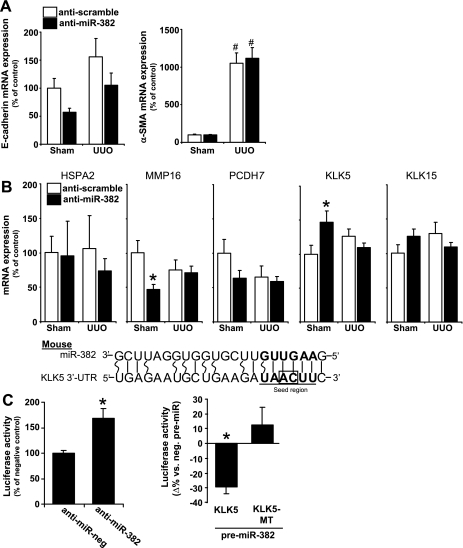

Fig. 1.

Increase in microRNA (miR)-382 with 3 days of unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) is prevented with intravenous locked nucleic acid (LNA)-modified anti-miR-382. A: left ureter obstruction or sham surgery was completed in CD-1 mice. The left kidney was collected for RNA isolation 1 or 3 days after surgery obstruction (n = 6/group). Expression of miR-382 was increased by severalfold in the left kidney after 3 days of UUO. *Significant different from sham-operated animals (P < 0.05). B: anti-miR-382 or anti-scrambled control oligonucleotides were delivered to mice by tail vein injection (10 mg/kg) prior to UUO or sham surgery and again after 24 h. The left kidney was isolated for mRNA isolation 3 days after surgery. Mice that received anti-scrambled treatment and underwent 3 days of UUO experienced a significant increase in miR-382 compared with their sham-operated controls (#P < 0.05). Anti-miR-382 treatment reduced expression of miR-382 in both sham and UUO-operated animals compared with their treatment controls (*P < 0.05). C: basal expression of miR-382 in various tissues expressed as percent of kidney expression. D: anti-miR-382 treatment effectively reduced miR-382 expression in kidney and brain (*P < 0.05). LV, left ventricle.

Intravenous LNA-anti-miR-382 Treatment Blocked an Increase in miR-382 with UUO

LNA anti-miR-382 delivery by tail vein completely blocked an increase in miR-382 expression in the kidney after 3 days of UUO, resulting in expression levels similar to that of sham mice treated with a control oligo (Fig. 1B). Additionally, anti-miR-382 significantly decreased basal levels of renal miR-382 in sham mice. miR-382 was expressed in all the tissues examined including kidney, liver, left ventricle, and brain (Fig. 1C). Intravenous treatment with anti-miR-382 suppressed miR-382 expression in the brain and tended to reduce expression in liver but did not affect the expression in the left ventricle (Fig. 1D).

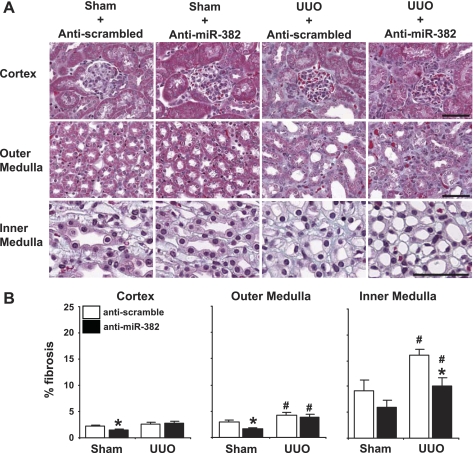

Suppression of miR-382 Attenuated Interstitial Fibrosis

The percent area of fibrotic tissue was measured in all regions of the kidney with trichrome straining (representative images, Fig. 2A). Three days of UUO significantly increased interstitial fibrosis in the outer medulla and inner medulla. Anti-miR-382 treatment substantially and significantly attenuated the increase specifically in the inner medulla, reducing the level of interstitial fibrosis in this kidney region to the level seen in sham mice treated with a control oligo (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, the anti-miR-382 treatment significantly reduced basal levels of extracellular matrix in both the cortex and outer medulla in sham mice.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of miR-382 prevented renal inner medullary interstitial fibrosis in UUO mice and reduced extracellular matrix content in sham mice. A: kidney sections were stained for fibrotic tissue (blue) with Masson's trichrome and photographed at ×20 magnification in 4 comparable radial paths from cortex to inner medulla. B: fibrosis expressed as percentage of total tissue area. Anti-miR-382 treatment reduced extracellular matrix content in the cortex and outer medulla of sham-operated mice. Any UUO induced inner medullary fibrosis was completely prevented with miR-382 knockdown. Calibration bar = 50 μm. Anti-scramble-treated n = 10/group, anti-miR-382 n = 8/group. *Significantly different from anti-scrambled-treated mice with same surgery (P < 0.05), #significantly different from sham-operated animals receiving the same anti-miR treatment.

Expression of Classic EMT Markers was not Altered With miR-382 Blockade

The expression of E-cadherin and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) was measured by real-time PCR in all treatment conditions. Anti-miR-382 treatment tended to suppress E-cadherin mRNA expression in both sham-operated and UUO kidneys, though this effect did not reach statistical significance. Anti-miR-382 had no effect on α-SMA expression (Fig. 3A). With no obvious changes in EMT markers in response to the anti-miR-382 treatment, we looked for other miR-382 targets that might be involved in the development of renal interstitial fibrosis.

miR-382 Targeted (chymo)Trypsin-like Peptidase Kallikrein 5

Several predicted mRNA targets of mouse miR-382 were identified by searching MicroCosm and Targetscan databases. Though we previously found miR-382 to target superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) in human cells (17), mouse SOD2 was not a predicted target of miR-382. To validate this, the expression of SOD2 mRNA was measured by real-time PCR. We found no evidence that miR-382 was targeting SOD2 mRNA in mice (data not shown).

We performed a literature search to identify other predicted miR-382 target genes that had been reported to have altered expression associated with UUO, fibrosis, or degradation of extracellular matrix proteins. The resulting list contained protocadherin 7 (PCDH7), matrix metalloproteinase 16 (MMP16), heat shock protein A2 (HSPA2), KLK5, and kallikrein 15 (KLK15). Expression of mRNA for these predicted targets was measured in all treatment groups (Fig. 3B). Sham mice treated with anti-miR-382 experienced a significant increase in renal KLK5 mRNA expression, leading us to further examine possible involvement of KLK5 in the effect of miR-382.

Luciferase reporter assays were performed to validate MicroCosm-predicted interactions between miR-382 and the 3′-UTR of mouse KLK5 mRNA. Blockade of endogenous miR382 by cotransfection of anti-miR-382 and a mouse 3′-UTR reporter construct significantly increased resulting luciferase activity compared with cotransfection of a control anti-miR (Fig. 3C). Conversely when cells were cotransfected with pre-miR-382 luciferase activity was significantly reduced. An inversion mutation in the predicted seed binding region of the 3′-UTR sequence prevented suppression of KLK5 by miR-382, confirming that miR-382 is interacting with the predicted seed region binding site. These data indicate that miR-382 is capable of suppressing KLK5 expression by interacting with KLK5 3′-UTR in mice.

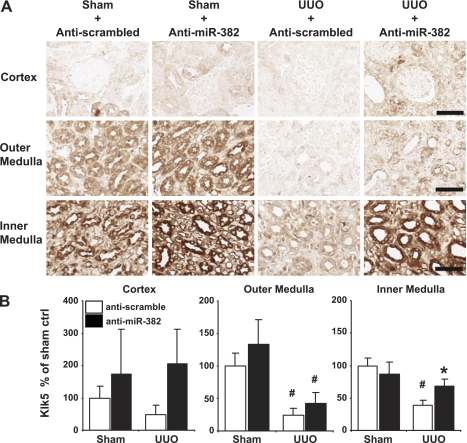

Inner Medullary KLK5 Expression was Reduced in UUO Mice and Restored With miR-382 Inhibition

Immunohistochemistry was utilized to determine if UUO or anti-miR-382 treatment produced regional changes in KLK5 protein expression and if those changes correlated with alterations in fibrosis. In all treatment groups KLK5 expression was highest in the inner medulla and lowest in the cortex (representative images, Fig. 4A). UUO resulted in a substantial and significant decrease in KLK5 abundance in the outer medulla and the inner medulla. Importantly, anti-miR-382 treatment significantly restored KLK5 abundance specifically in the inner medulla (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

KLK5 expression in the inner medulla was reduced by UUO and restored by miR-382 blockade. A: representative images of KLK5 expression in the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla of mouse kidneys from all treatment groups. Calibration bar = 50 μm. B: KLK5 expression as percent of area normalized optical density of sham + anti-scramble-treated mice as described in materials and methods. Anti-miR-382 treatment increased KLK5 expression in the inner medulla of UUO-operated mice compared with anti-scrambled control. Anti-scrambled-treated n = 10/group, anti-miR-382 n = 8/group. *Significantly different from anti-scrambled-treated mice with same surgery (P < 0.05), #significantly different from sham-operated animals receiving the same anti-miR treatment.

We measured the mRNA abundance of KLK5 in the inner medulla using real-time PCR. Inner medulla tissues were recovered from FFPE sections, and total RNA extracted using a PureLink FFPE Total RNA Isolation kit (Invitrogen). Despite the use of very small amounts of RNA extracted from FFPE sections, technically reproducible real-time PCR data were obtained from ∼85% of the samples. With KLK5 mRNA levels in the sham + anti-scramble group (n = 7) set as 100%, UUO + anti-scramble tended to decrease KLK5 mRNA levels to 55% ± 15% (n = 9) without reaching statistical significance (P = 0.20). Anti-miR-382 treatment in UUO mice increased the abundance of KLK5 mRNA by nearly threefold to 154% ± 56% (n = 6, P = 0.06 vs. UUO + anti-scramble). Anti-miR-382 did not significantly change KLK5 mRNA levels in sham mice (128% ± 32%, n = 6).

Renal Regional Distribution of miR-382 and its Response to UUO and anti-miR-382 Treatment

We used ISH for miR-382 to determine the kidney regions where miR-382 expression was augmented with UUO and suppressed with anti-miR-382 treatment. miR-382 expression was measured in the cortex, outer medulla, and inner medulla under all experimental conditions (representative images, Fig. 5A). We found that UUO induced an increase in miR-382 levels most significantly in the outer and inner medulla and that this increase was completely prevented in both regions with anti-miR-382 treatment (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

UUO increased miR-382 in the renal medulla, which was blocked by anti-miR-382. A: representative images of miR-382 expression in mouse kidney sections obtained by in situ hybridization. Calibration bar = 50 μm. B: miR-382 expression as percent average integrated optical density of sham + anti-scrambled-treated mice. Sequential photographs were obtained at ×20 magnification in 4 comparable radial paths from cortex to inner medulla. The increase in miR-382 expression was significant in both the outer and inner medulla of UUO + anti-scrambled-treated mice, with the inner medulla showing the highest level of expression. Intravenous administration of anti-miR-382 effectively knocked down miR-382 expression throughout the kidney, reaching statistical significance in the renal medulla. Anti-scrambled treated n = 10/group, anti-miR-382 n = 8/group. *Significantly different from anti-scrambled-treated mice with same surgery (P < 0.05), #significantly different from sham-operated animals receiving the same anti-miR treatment.

Renal KLK5 Mediated the Protective Effect of miR-382 Blockade Against Inner Medullary Fibrosis

Mice treated with either anti-miR-382 or anti-scrambled control underwent UUO. The ligated kidney was treated locally with KLK5 siRNA or control siRNA by retrograde injection. Real-time PCR measurements of whole kidney RNA determined the anti-miR-382 and KLK5 siRNA treatments were effective in suppressing their targets compared with control injected animals (53.8% and 23.6% reduction in the level of miR-382 and KLK5 mRNA, respectively, P < 0.05 vs. mice receiving respective control oligonucleotides). The effectiveness of the anti-miR-382 and KLK5 siRNA treatments was further confirmed by ISH of miR-382 and immunohistochemical analysis of KLK5 protein, respectively (representative images, Fig. 6A). Fibrosis quantification from Trichrome-stained tissues indicated that anti-miR-382-treated mice with renal knockdown of KLK5 were not protected from developing inner medullary fibrosis (Fig. 6, A and B).

Fig. 6.

Direct siRNA-mediated suppression of KLK5 in the UUO kidney promoted inner medullary fibrosis despite miR-382 blockade. A: representative images of the inner medulla with trichrome staining, miR-382 in situ hybridization, and KLK5 immunohistochemistry from animals undergoing UUO surgery and receiving a combination of KLK5 or control siRNA (ureteral delivery) and anti-miR-382 or control anti-miR (intravenous delivery). Calibration bar = 50 μm. B: fibrosis expressed as percentage of total tissue area. In the inner medulla specifically, the anti-miR-382 treatment reduced fibrosis in kidneys receiving the control siRNA, while miR-382 blockade was not effective in attenuating fibrosis when KLK5 expression was reduced by siRNA (n = 5–7/group). *Significantly different from anti-miR-382 treatment with control siRNA (P < 0.05), #significantly different from anti-scrambled-treated animals receiving control siRNA.

DISCUSSION

The present study was the first demonstration of an in vivo functional role of miR-382 in any species and any organ system. Our laboratory previously reported a role of miR-382 in mediating TGF-β1-induced loss of epithelial characteristics in cultured human renal epithelial cells (17). In addition, miR-382 has been reported to contribute to the latency of HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells (14), and its expression is altered in acute myeloid leukemia (21). However, in vivo functional roles of miR-382 were unknown until the present study. Knockdown of miR-382 in vivo allowed us to demonstrate the important contribution of miR-382 to interstitial fibrosis in the inner medulla and basal extracellular matrix abundance in the mouse kidney.

The novel findings that miR-382 targets KLK5 and that the protective effect of miR-382 blockade against fibrosis was abolished by renal knockdown of KLK5 suggest that miR-382 might contribute to interstitial fibrosis by compromising extracellular matrix degradation. The involvement of compromise of extracellular matrix degradation in the development of pathological fibrosis in the kidney has been well established (11, 28). Here we show that KLK5 may be another important regulator of matrix remodeling during UUO-induced fibrosis. KLK5 is a member of the kallikrein gene family contained in a highly conserved cluster (35). Many kallikreins do not have well-characterized promoters or even characteristic promoter motifs, leading to the suggestion that miRNAs might be particularly important posttranscriptional regulators of kallikreins (4). KLK5 is a particularly interesting kallikrein. KLK5 is a (chymo)trypsin-like proteinase that mediates degradation of many extracellular matrix proteins including collagens I–IV, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and laminin (26, 29). In addition, there is substantial evidence that KLK5 is a master regulator of other kallikrein inactive zymogens, acting to cleave many inactive pro-KLKs into their active extracellular matrix protein-degrading forms (2, 6, 27, 34).

miR-382 and KLK5 appear to be involved in the development of renal interstitial fibrosis in a region-specific manner, each showing increasing levels of expression moving from the cortex to the inner medulla under all conditions of this study. In fact our data indicate low levels of expression of both genes in the cortex, suggesting that KLK5 is not likely to be key regulator of disease-related fibrosis in this region. Numerous profibrotic and antifibrotic factors participate in maintaining or disturbing the balance between extracellular matrix generation and degradation. It is not surprising that the significance of specific pro- or antifibrotic factors varies among kidney regions. In this regard, we have previously shown distinct differences in miRNA and target protein expression in the renal cortex and medulla (33). The heterogeneous nature of the kidney regions made it particularly informative to measure regional expression changes in histological sections in the current study. The differences in the levels of fibrosis, miR-382, and KLK5 in the inner medulla were large among experimental groups, mitigating any concerns about the limited ability of immunohistochemistry or ISH to allow quantitative comparisons.

The mRNA analysis of EMT markers and predicted miR-382 targets in whole kidney homogenate shown in Fig. 3, A and B, was intended as a screening experiment to nominate most readily identifiable mediators of the effect of miR-382. One should be cautious not to overinterpret these data. Expression measurements in homogenized kidney tissue could mask significant changes in expression in a specific region of the kidney. This is an important point to consider when interpreting the whole kidney KLK5 mRNA expression data, which would give the impression that anti-miR-382 treatment was ineffective in increasing KLK5 expression in kidneys subjected to UUO. In fact, when KLK5 mRNA levels were measured in the inner medulla only, the result was qualitatively consistent with immunohistochemical analysis of KLK5 protein in this kidney region (i.e., decrease of KLK5 with UUO and restoration by anti-miR-382). The mRNA and immunohistochemistry data in the inner medulla were not quantitatively identical. For example, the decrease of KLK5 with UUO was statistically significant only in the immunohistochemistry data. These data suggest that the effect of miR-382 on KLK5 expression might be region-specific in the kidney and could involve translational repression and/or mRNA degradation, although recent analysis has suggested that miRNAs affect the abundance of target mRNA in most cases (12).

Interstitial fibrosis in the renal medulla is an important yet underappreciated pathological alteration. The understanding of renal medullary fibrosis in patients is limited because the renal medulla, particularly the inner medulla, is often inaccessible in clinical renal biopsy. However, significant renal medullary fibrosis associated with various types of human chronic kidney disease has been reported in studies in which the medulla was specifically examined (7, 9). In addition, medullary fibrosis is a prominent feature in several animal models of chronic renal injury including hypertensive renal injury (24).

In summary, this study provides evidence of a completely novel mechanistic pathway in which upregulation of miR-382 contributes to the development of renal inner medullary interstitial fibrosis in mice, which is at least in part mediated by targeting of KLK5.

GRANTS

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health Grants HL-085267, DK-084405, HL-082798, HL-029587, and a CTSI grant (to M. Liang).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AJK and ML designed the study and wrote the manuscript. AJK, YL, BC, KU, and YL performed the experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136: 215– 233, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brattsand M, Stefansson K, Lundh C, Haasum Y, Egelrud T. A proteolytic cascade of kallikreins in the stratum corneum. J Invest Dermatol 124: 198– 203, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Callis TE, Pandya K, Seok HY, Tang RH, Tatsuguchi M, Huang ZP, Chen JF, Deng Z, Gunn B, Shumate J, Willis MS, Selzman CH, Wang DZ. MicroRNA-208a is a regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and conduction in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 2772– 2786, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chow TF, Crow M, Earle T, El-Said H, Diamandis EP, Yousef GM. Kallikreins as microRNA targets: an in silico and experimental-based analysis. Biol Chem 389: 731– 738, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chung AC, Huang XR, Meng X, Lan HY. miR-192 mediates TGF-beta/Smad3-driven renal fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1317– 1325, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Debela M, Beaufort N, Magdolen V, Schechter NM, Craik CS, Schmitt M, Bode W, Goettig P. Structures and specificity of the human kallikrein-related peptidases KLKs 4, 5, 6, and 7. Biol Chem 389: 623– 632, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dell'Antonio G, Randhawa PS. “Striped” pattern of medullary ray fibrosis in allograft biopsies from kidney transplant recipients maintained on tacrolimus. Transplantation 67: 484– 486, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eulalio A, Huntzinger E, Izaurralde E. Getting to the root of miRNA-mediated gene silencing. Cell 132: 9– 14, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Evan AP, Lingeman J, Coe F, Shao Y, Miller N, Matlaga B, Phillips C, Sommer A, Worcester E. Renal histopathology of stone-forming patients with distal renal tubular acidosis. Kidney Int 71: 795– 801, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Filipowicz W, Bhattacharyya SN, Sonenberg N. Mechanisms of post-transcriptional regulation by microRNAs: are the answers in sight? Nat Rev Genet 9: 102– 114, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gobet R, Bleakley J, Cisek L, Kaefer M, Moses MA, Fernandez CA, Peters CA. Fetal partial urethral obstruction causes renal fibrosis and is associated with proteolytic imbalance. J Urol 162: 854– 860, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466: 835– 840, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Harris RC, Neilson EG. Toward a unified theory of renal progression. Annu Rev Med 57: 365– 380, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang J, Wang F, Argyris E, Chen K, Liang Z, Tian H, Huang W, Squires K, Verlinghieri G, Zhang H. Cellular microRNAs contribute to HIV-1 latency in resting primary CD4+ T lymphocytes. Nat Med 13: 1241– 1247, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 119: 1420– 1428, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kato M, Putta S, Wang M, Yuan H, Lanting L, Nair I, Gunn A, Nakagawa Y, Shimano H, Todorov I, Rossi JJ, Natarajan R. TGF-beta activates Akt kinase through a microRNA-dependent amplifying circuit targeting PTEN. Nat Cell Biol 11: 881– 889, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kriegel AJ, Fang Y, Liu Y, Tian Z, Mladinov D, Matus IR, Ding X, Greene AS, Liang M. MicroRNA-target pairs in human renal epithelial cells treated with transforming growth factor beta1: a novel role of miR-382. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 8338– 8347, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W. The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet 11: 597– 610, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krupa A, Jenkins R, Luo DD, Lewis A, Phillips A, Fraser D. Loss of MicroRNA-192 promotes fibrogenesis in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 438– 447, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lai LW, Chan DM, Erickson RP, Hsu SJ, Lien YH. Correction of renal tubular acidosis in carbonic anhydrase II-deficient mice with gene therapy. J Clin Invest 101: 1320– 1325, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Z, Lu J, Sun M, Mi S, Zhang H, Luo RT, Chen P, Wang Y, Yan M, Qian Z, Neilly MB, Jin J, Zhang Y, Bohlander SK, Zhang DE, Larson RA, Le Beau MM, Thirman MJ, Golub TR, Rowley JD, Chen J. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia with common translocations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 15535– 15540, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Y. Renal fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int 69: 213– 217, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Liu Y. New insights into epithelial-mesenchymal transition in kidney fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 212– 222, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu Y, Taylor NE, Lu L, Usa K, Cowley AW, Jr, Ferreri NR, Yeo NC, Liang M. Renal medullary microRNAs in Dahl salt-sensitive rats: miR-29b regulates several collagens and related genes. Hypertension 55: 974– 982, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu Y, Singh RJ, Usa K, Netzel BC, Liang M. Renal medullary 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Physiol Genomics 36: 52– 58, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Michael IP, Sotiropoulou G, Pampalakis G, Magklara A, Ghosh M, Wasney G, Diamandis EP. Biochemical and enzymatic characterization of human kallikrein 5 (hK5), a novel serine protease potentially involved in cancer progression. J Biol Chem 280: 14628– 14635, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michael IP, Pampalakis G, Mikolajczyk SD, Malm J, Sotiropoulou G, Diamandis EP. Human tissue kallikrein 5 is a member of a proteolytic cascade pathway involved in seminal clot liquefaction and potentially in prostate cancer progression. J Biol Chem 281: 12743– 12750, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peters CA, Freeman MR, Fernandez CA, Shepard J, Wiederschain DG, Moses MA. Dysregulated proteolytic balance as the basis of excess extracellular matrix in fibrotic disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 272: R1960– R1965, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rajapakse S, Ogiwara K, Yamano N, Kimura A, Hirata K, Takahashi S, Takahashi T. Characterization of mouse tissue kallikrein 5. Zoolog Sci 23: 963– 968, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ricardo SD, van Goor H, Eddy AA. Macrophage diversity in renal injury and repair. J Clin Invest 118: 3522– 3530, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Rooij E, Olson EN. MicroRNAs: powerful new regulators of heart disease and provocative therapeutic targets. J Clin Invest 117: 2369– 2376, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schainuck LI, Striker GE, Cutler RE, Benditt EP. Structural-functional correlations in renal disease. II The correlations. Hum Pathol 1: 631– 641, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tian Z, Greene AS, Pietrusz JL, Matus IR, Liang M. MicroRNA-target pairs in the rat kidney identified by microRNA microarray, proteomic, and bioinformatic analysis. Genome Res 18: 404– 411, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoon H, Laxmikanthan G, Lee J, Blaber SI, Rodriguez A, Kogot JM, Scarisbrick IA, Blaber M. Activation profiles and regulatory cascades of the human kallikrein-related peptidases. J Biol Chem 282: 31852– 31864, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yousef GM, Chang A, Scorilas A, Diamandis EP. Genomic organization of the human kallikrein gene family on chromosome 19q13.3-q134. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 276: 125– 133, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zeisberg M, Neilson EG. Mechanisms of tubulointerstitial fibrosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 1819– 1834, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]