Abstract

Pain, redness, heat, and swelling are hallmarks of inflammation that were recognized as early as the first century AD. Despite these early observations, the mechanisms responsible for swelling, in particular, remained an enigma for nearly two millennia. Only in the past century have scientists and physicians gained an appreciation for the role that vascular endothelium plays in controlling the exudation that is responsible for swelling. One of these mechanisms is the formation of transient gaps between adjacent endothelial cell borders. Inflammatory mediators act on endothelium to reorganize the cytoskeleton, decrease the strength of proteins that connect cells together, and induce transient gaps between endothelial cells. These gaps form a paracellular route responsible for exudation. The discovery that interendothelial cell gaps are causally linked to exudation began in the 1960s and was accompanied by significant controversy. Today, the role of gap formation in tissue edema is accepted by many, and significant scientific effort is dedicated toward developing therapeutic strategies that will prevent or reverse the endothelial cell gaps that are present during the course of inflammatory illness. Given the importance of this field in endothelial cell biology and inflammatory disease, this focused review catalogs key historical advances that contributed to our modern-day understanding of the cell biology of interendothelial gap formation.

Keywords: inflammation, permeability, transport, junctions, endothelium

endothelium forms a semipermeable barrier regulating the traffic of water, low molecular weight solutes, and proteins between blood and tissue. In the healthy, undisturbed, continuous endothelium, water and small molecular weight solutes move across the endothelial barrier through a paracellular pathway: the interendothelial cleft. Macromolecules such as albumin exit the circulation via a transcellular route, through a complex system of vesicular transport: caveolae and vesiculovacuolar organelles (see Ref. 78 for a comprehensive review). However, under pathological conditions such as anaphylaxis and sepsis, fluid and molecules exit the blood through gaps that form between endothelial cells (i.e., by the paracellular route) (112). Indeed, interendothelial gaps serve as a pathway of exudation across blood vessels of solutes and fluid, and many consider them a distinctive feature of acute inflammation (31, 36).

Over the past 30 years, a substantial body of evidence has illustrated that inflammatory mediators and vascular permeability-increasing compounds cause actomyosin-based contraction, reorganize peripheral microtubules, and uncouple tight junctions, adherens junctions, and focal adhesions. Such cytoskeletal reorganization has been shown to retract endothelial cell-cell borders and provides a paracellular pathway for increased permeability. The evidence demonstrating that evolving or persistent gaps contribute to tissue edema has resulted in a significant effort to prevent or reverse gap formation as an anti-inflammatory paradigm (49, 63).

Although interendothelial cell gap formation is accepted by many as a cause of tissue edema (36), this perception is not universally held. In this context, some of the historical hallmarks that brought about our current understanding of the highly regulated biology of interendothelial gap formation will be addressed in this review. Although many believe that interendothelial gaps and vascular permeability are interconnected, a general review of microvascular permeability or tissue (i.e., pulmonary) edema is beyond the scope of this article, since these topics have been extensively examined elsewhere (75, 81). Nevertheless, it is critical to recognize that the work of giants including Starling (106), Landis (59), Pappenheimer (88), and Curry and Michel (24) in the field of microvascular permeability in general and that of Guyton (44), Staub (108), Taylor (113), Brigham (14), Parker (90), and Bhattacharya (9, 10, 56), among others, in the subject of lung microvascular permeability in particular laid essential groundwork for an understanding of how interendothelial cell gaps enable tissues to become edematous. In a further effort to focus this review, seminal observations of cell signaling and molecular determinants that play a role in gap formation will not be addressed, since these topics have been discussed by other investigators (31, 68, 78). Likewise, this historical review will not consider the role played by the glycocalyx, vesicular transport, transendothelial gaps, and the interstitium in the formation of tissue edema.

Resolving the Interendothelial Cell Gap

Injury → vascular leak → edema.

A road map to understanding the role played by the vasculature in the pathogenesis of inflammation was proposed more than 125 years ago. As early as 1889, scientists recognized the following still-standing concepts. First, they had identified the endothelium (103, 114). Second, they knew that endothelial cells in venules and capillaries are held together by intercellular “cement” (19; p. 295). Third, they recognized that during inflammation leukocytes emigrate from the vasculature through “capillary veins” or venules (19; p. 251). Fourth, they appreciated that injured tissues are capable of inducing changes in blood vessels and leukocytes (19). And fifth, they knew that the aforementioned changes cause pain, redness, heat, and swelling (19), the hallmarks of inflammation that were described by Celsus in the first century AD (57).

Although these concepts were recognized in the late 1800s, they were not firmly accepted by the scientific community at that time. Different schools of thought attributed the signs and symptoms of inflammation to changes in either the blood itself, the nerves and muscle of the blood vessels, the tissue surrounding the capillaries, or the capillary walls (117). Cohnheim first proposed the latter theory in 1873 (29). Using intravital microscopy in three animal models of tissue injury (a frog's tongue, a frog's mesentery, and a rabbit's ear), he visualized changes in the microcirculation never before described. He saw leukocytes exiting the venules of these tissues accompanied by fluid accumulation and pus formation (19). Cohnheim concluded that the primary cause of pus formation was a “molecular impairment” of the walls of the vessels through which fluid media and cells could extravasate into the surrounding tissues (29, 117). This theory was controversial, especially since it contrasted with the most widely accepted idea of the time, which was a theory advanced by Cohnheim's mentor, Virchow (35, 70). Virchow believed that inflammation was due to the tissue response to irritants that attract and retain substances out of the blood (117). These ideas primed the field for the discovery of inflammatory mediators as a cause of edema formation.

Injury → inflammatory mediators → vascular leak → edema.

Cohnheim's proposition was not fully embraced until Dale published a series of studies between 1910 and 1920 on a compound capable of inducing inflammation (25–27). Dale named this compound histamine (27). He noted that when histamine was locally applied to a dog limb, the volume of the limb increased, a sign of vascular leak (26). When topically applied to the skin of cats, histamine induced the same pain, redness, heat, and swelling attributed to inflammation (25). Moreover, Dale observed that when histamine was injected intravenously, the animals showed signs and symptoms of what we now recognize as anaphylactic shock (25).

The confirmation of Cohnheim's theory came in 1921, when Lewis, in an elegant paper using a model of patients affected with urticaria, reported how injured skin released a histamine-like substance that induced pain, redness, heat, and swelling (65). Although Lewis did not confirm that the substance was in fact histamine, this paper was instrumental for the development of a unified theory of inflammation. First, this report supported previous observations by Bernard and Heidenhain that substances secreted by undisturbed tissues can affect blood flow (79). Second, it confirmed Dale's findings in which chemical compounds were able to induce inflammation without irreversibly damaging the vascular barrier. And third, by showing that tissues were capable of elaborating factors that cause pain, redness, heat, and swelling, it unified Cohnheim's and Virchow's independent ideas.

Following the previous observations, scientists sought to identify the vascular site through which edema-causing fluid leaked. Several reports proposed that the edema caused by histamine, and by newly discovered histamine-like substances such as serotonin (97) and bradykinin (98), was the consequence of increased vascular permeability through capillaries (28, 74). In contrast to these reports, in 1940 Chambers proposed that the cause of inflammatory edema was not an increase in permeability through the capillary endothelial cells, but actually a defect between the endothelial cells (16). While perfusing the frog's mesentery with a “carbon solution,” he concluded that a “softening of the cement” of endothelial cells could be induced by alkalosis in the presence of nominal perfusate Ca2+. He interpreted the data to mean that the amount of edema detected correlated with the softening of the intercellular cement. In this seminal paper, he recognized that Cohnheim had actually introduced the concept of intercellular cement around 1887 (15, 19).

This idea that edema is caused by increased capillary filtration, either through or between capillary endothelial cells, was already supported by the accepted concepts of Starling that fluid leak represents a balance between vascular and interstitial hydrostatic and oncotic pressure (106), Krogh's capillary dynamics (53–55), and Landis' transcapillary fluid movement (59, 60). However, direct microscopic evidence of increased capillary permeability leading to edema did not exist, and, moreover, there was disagreement over the previous definition of a capillary (71).

By the end of the 1950s the three observations made in the previous century had been confirmed in a more mechanistic way: the hallmarks of inflammation were known to be caused by the increase in blood vessel permeability, injured tissue was known to release substances such as histamine and serotonin that increase blood vessel permeability, and endothelial cells were acknowledged as being held together by an intercellular cement that was Ca2+ dependent. It was now evident that during inflammation a breach in the endothelial cell barrier enabled the uncharacteristic passage of proteins and fluid into tissue (88). Nevertheless, it was unclear how the permeability-increasing agents worked, and the vascular segment, or segments, affected by inflammation were uncertain, since there was no anatomical evidence for increased capillary permeability in inflammation. These observations laid the groundwork for the discovery of the impairment of endothelial cell junctional apposition as a cause of vascular leak.

Injury → inflammatory mediators → interendothelial cell gap → vascular leak → edema.

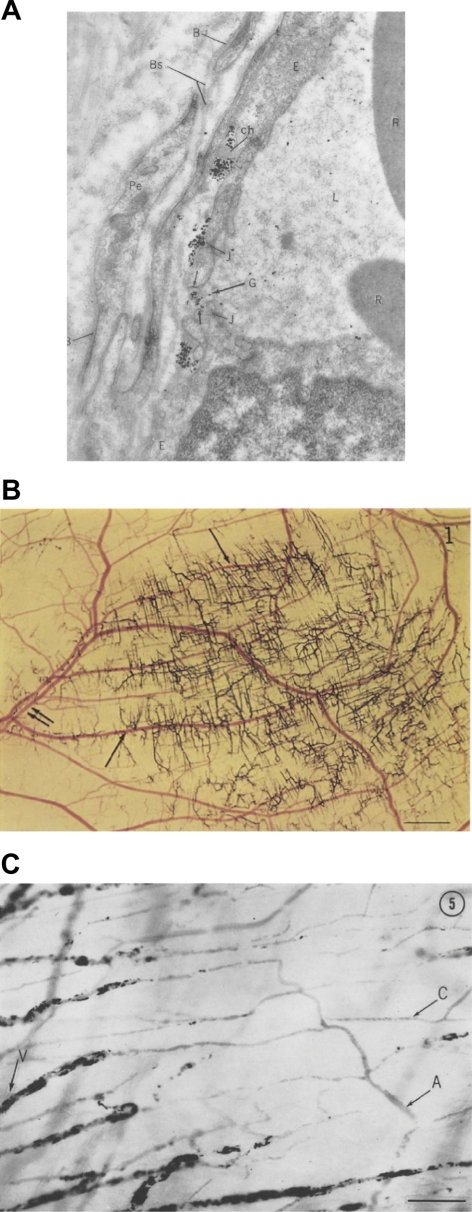

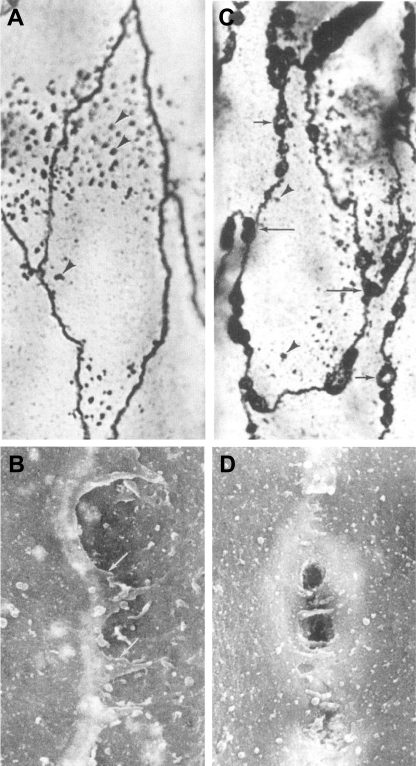

With the start of the second half of the twentieth century came extensive advancements in imaging, particularly at the ultrastructural level. In 1961, Majno and Palade took advantage of the electron microscope to study how histamine and serotonin cause vascular leakage. Together they demonstrated that vascular leakage occurred in postcapillary venules, and not in capillaries of the systemic circulation (71) (Fig. 1). Moreover, they showed that this leakage occurred when adjacent endothelial cells “loosened their grip on one another,” forming interendothelial gaps (70, 122). These startling observations are considered classics in endothelial biology for several reasons. They were the first to pinpoint Cohnheim's, Virchow's, Dale's, and Lewis' observations at the cellular level. They confirmed Cohnheim's observation on the role of venules in inflammation. They validated Chambers' proposition of interendothelial cement. Finally, they hinted at the concept of endothelial cell heterogeneity, that not all endothelia are the same, by demonstrating that endothelial cells that were only micrometers apart responded differently to the same stimulus. Interestingly, Alksne had approached the same hypothesis with the same experimental techniques, had gotten the same results, but had not interpreted the results to mean that these agonists were inducing interendothelial cell gaps (3, 122). According to Majno, Alksne had not considered the existence of the basement membrane (3).

Fig. 1.

A: endothelial cells forming intercellular gaps (G). Magnification 50,000. B: carbon perfusate leaving the vascular tree after local injection of histamine. Single arrows, venules; double arrows, arterioles. Scale = 1 mm. C: carbon labeling of leaking vessels after local injection of histamine. Scale 100 mm. [From original figures published by Majno (70, 71).]

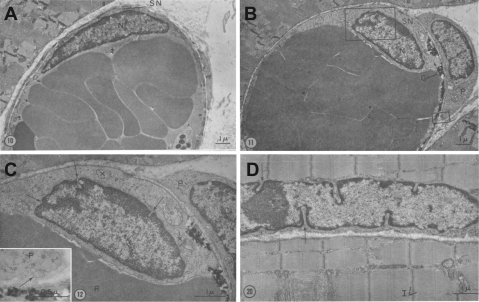

By the end of the 1960s, Majno had published a series of papers that shed light on the mechanism by which inflammatory mediators induce endothelial cell gaps in venules. He proposed that permeability-increasing agents like histamine and serotonin induce gaps by causing active endothelial cell contraction in postcapillary venules (69, 72). He observed that inflammatory agonists cause nuclei of venular endothelial cells to display deep membrane indentations, which he interpreted to be morphological evidence of cell shortening and, hence, cell contraction (Fig. 2). This idea was controversial, since he had not directly measured cell contraction. However, Majno's hypothesis was subsequently supported by studies from Becker (7, 8) and Giacomelly (41), who identified contractile proteins in endothelial cells. However, since endothelial cells had not been isolated in culture, these data did not rule out that these contractile proteins belonged to other cells (i.e., smooth muscle cells).

Fig. 2.

A: venule endothelial cell fixed with venous congestion. Note the elongated and flattened nucleus. B: venule endothelial cell fixed with venous congestion 6 min after histamine treatment. Note the change in the shape of the nucleus. C: inset from B. Arrows point to nuclear indentations that Majno interpreted as evidence for endothelial cell contraction. D: striated muscle fiber fixed in state of contraction. Arrows point to nuclear indentations. [From original figures published by Majno (72).]

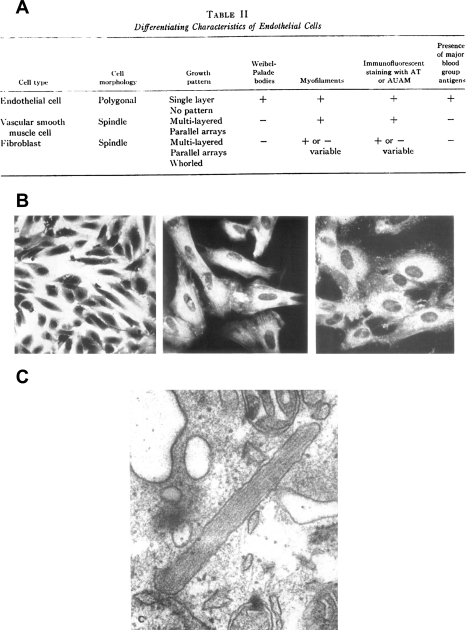

Majno's studies represented the first major step toward a mechanistic understanding of interendothelial cell gap formation. Yet the ideas proposed by Majno had not been tested in purified endothelial cell populations, and to this point in time endothelial cells could not be studied in culture. Thus another significant era in the study of gap formation, and in endothelial biology, began with the first attempt to isolate human umbilical vein endothelial cells by Maruyama in 1963 (84), which was successfully duplicated by Fryer in 1966 (34). Although these reports were important, they never went beyond a morphological characterization of the isolated cells; the systematic characterization of human endothelial cells was not reported until 1973. In back-to-back papers that are considered the beginnings of modern vascular biology (85), Jaffe and Nachman unequivocally isolated human umbilical vein endothelial cells, and identified them not only by their morphological attributes (51), but also by their immunohistochemical and functional markers (50) (Fig. 3). At the time endothelium was thought to “live in blood,” and hence the isolation of endothelial cells in culture was received with great skepticism (11). Nevertheless, Gimbrone in 1974 (42), Henriksen in 1975 (45), and Ryan in 1978 (99) followed Jaffe's success. These investigators reported not only a cell isolation technique, but also the first endothelial cell identification markers. In addition, they primed the vascular biology community for the systematic study of the mechanisms regulating cytoskeletal dynamics as being pivotal in the study of interendothelial gap formation for decades to come.

Fig. 3.

A: morphological and biochemical characterization for cultured endothelial proposed by Jaffe in 1973. B, left: photomicrograph of cultured endothelial cells. Center: positive immunofluorescence for actomyosin in cultured endothelial cells. Right: positive immunofluorescence for factor VIII in cultured endothelial cell (50). Transmission electron micrograph of Weibel-Palade body in cultured endothelial cells. Magnification ×95,000 (51). [From original figures published by Jaffe and collaborators (50, 51) with permission from American Society for Clinical Investigation.]

Injury → inflammatory mediators → cytoskeletal reorganization → interendothelial cell gap → vascular leak → edema.

Using these in vitro endothelial systems, investigators were able to isolate, characterize, and systematically subculture endothelial cells to test hypotheses that were impossible to address in the past. For example, how do permeability-increasing factors induce contraction of endothelial cells? What is the molecular basis of endothelial cell contraction? What are the molecular components of Chambers' intercellular cement? What is the role of the cytoskeleton in endothelial cell contraction? And do interendothelial cell gaps really cause an increase in permeability?

Answers to these questions came in the 1970s and 1980s with the studies of McDonald, Lauweryns, and Shasby. McDonald et al. (77) reported that thrombin induces gaps in cultured endothelial cells. Using human, bovine, and canine aortic endothelial cells, he described extensive thrombin-induced changes in cell shape, which he concluded were similar to the rounding observed in thrombin-treated platelets.

Lauweryns et al. (62) used electron microscopy to describe changes in the actin fibers of pulmonary lymphatic endothelial cells from neonatal rabbits incubated with meromyosin. He found that microfilaments (actin), and not thick filaments (microtubules), bundled following incubation with meromyosin. This is the original description of actin stress fibers in endothelium. Lauweryns concluded that these filaments could “assist in the active regulation of intercellular gaps,” supporting the hypothesis advanced by Majno, Becker, and Giacomelly of a contractile apparatus within endothelial cells.

While the field was moving toward an understanding that active endothelial contraction contributes to maintenance in cell shape, and to the formation of intercellular gaps, some experiments contrasted this general idea. Shasby et al. (104) treated bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells with the actin depolymerizing agent cytochalasin and demonstrated that by depolymerizing actin in these cells the monolayer formed gaps. In the same article, they went on to demonstrate a direct relationship between gap formation, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and increased albumin transit across the monolayer. Although this paper shed light on involvement of the cytoskeleton in gap formation, it also added to the controversy on whether endothelial cell contraction was the cause of gaps. At the time, it was clear that polymerized actin was required for the tension generated during cell contraction.

For some, cultured endothelial cell systems do not reflect the physiology of an intact blood vessel. Nevertheless, McDonald, Lauweryns, and Shasby built the foundation for the study of mechanisms responsible for interendothelial cell gap formation. Their papers laid the ground work for Laposata's (61) systematic description of thrombin-induced gap formation, Garcia and Malik's (39) resolution of the link between thrombin-induced interendothelial cell gaps and increased permeability, Shepard's (105) report that changes in cell volume were sufficient to increase endothelial cell monolayer permeability to macromolecules, Alexander's (2) demonstration that actin-stabilizing agents enhanced endothelial barrier function, and Wysolmerski's (128) postulation that endothelial cell changes in shape, and hence integrity of the vascular barrier, is an active process requiring ATP-dependent, cytoskeletal-generated tension. It was becoming clear that actin actively participates in contractile events that control endothelial cell shape.

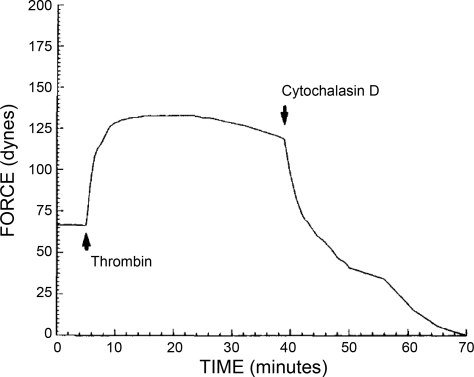

Early in the 1990s, mechanistic studies began to reveal the molecular basis for this actin-based contraction. Using bovine pulmonary artery endothelial cells, Wysolmerski (128) demonstrated that endothelial cell contraction, which he termed retraction, was dependent on the availability of ATP, Ca2+, and myosin light chain kinase. Moreover, he showed that myosin light chain kinase and myosin light chain phosphorylation were upstream of stress fiber formation in the contraction process of endothelial cells (126, 127). Wysomerski was also instrumental in settling the “endothelial contraction controversy” when in 1992 he and Kolodney reported that human umbilical vein endothelial cells were capable of generating tension after thrombin treatment. Additionally, they showed that a complete actin cytoskeleton was fundamental for this phenomenon to occur (52) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Graph shows a tracing of the isometric force generated by human umbilical vein endothelial cells exposed to 1 U/ml thrombin. Note how cytochalasin D abolished the thrombin-induced isometric force. [From original figures published by Kolodney and Wysolmerski (52).]

However, when the molecular machinery that participated in endothelial cell contraction was compared with that of other known contractile cells such as smooth muscle, it was discovered to be atypical. This observation was first brought to light by Garcia and collaborators when they reported that Ca2+ alone was necessary, but, however, insufficient, to increase myosin light chain phosphorylation, interendothelial gap formation, and permeability (37). This study resulted in the cloning of a unique “endothelial cell myosin light-chain kinase” by the same team two years later (38). This myosin light chain kinase isoform was larger than that traditionally seen in smooth muscle and became known as the “long form” of myosin light chain kinase. It turned out that in separate studies Watterson (121) had described an embryonic form of myosin light chain kinase, also a long form, that later was identified as the same isoform cloned by the Garcia group. These studies on the ability of the endothelium to undergo dynamic changes in cell tension, mediated by classic contractile proteins, led other research groups to investigate the role of the cell matrix as well as cell-cell contacts in the pathophysiology of interendothelial cell gaps.

Injury → inflammatory mediators → cytoskeletal, cell-cell, and cell-matrix reorganization → interendothelial cell gap → vascular leak → edema.

While cell biologists sought to determine molecular underpinnings of the cytoskeleton that were responsible for gap formation, Ingber introduced a novel concept of “cellular tensional integrity,” or cellular tensegrity in 1993 (48, 119). Cellular tensegrity utilized modern-day architectural and engineering criteria to explain the cytoskeletal basis for cell shape change. Cellular shape and contraction are the result of centripetal tension in contraposition to centrifugal traction. In this model, actomyosin is responsible for the centripetal forces, while cell-cell, cell-extracellular matrix adhesions, and microtubules control the centrifugal pull. Reorganization of constitutive cellular forces, from one that favored centripetal forces to one that favored centrifugal forces, was considered essential to generating interendothelial cell gaps.

The field had considered concepts germane to the tensegrity model in the previous decade, with studies on the cytoskeletal role in endothelial cell contraction. To add to this, new studies suggested that not only endothelial cell contraction (centripetal forces) but also cell-cell and cell- extracellular matrix interactions (centrifugal pull) were key in the development of interendothelial gaps. Partridge and Malik reported in 1992 that TNF-α induced interendothelial cell gap formation and increased endothelial permeability by the formation of actin stress fibers and by decreasing cell-extracellular matrix contacts (92). In the same year Lampugnani and Dejana described an increase in the permeability of horseradish peroxidase through endothelial cell monolayers when the monolayer was treated with antibodies against a novel “endothelial-specific cadherin” (58). This molecule turned out to be VE-cadherin (30), and what Lampugniani and Dejana disrupted with their antibody were endothelial adherens junctions.

Nonetheless, whether endothelial cell contraction with or without intercellular junction disruption was necessary and sufficient to cause endothelial cells gaps remained unclear. Shasby and colleagues approached this issue in 1996. They reported that histamine decreased human umbilical vein endothelial cell monolayer resistance, a measure of endothelial barrier integrity, without causing endothelial contraction. However, they also noted that thrombin caused the same drop in endothelial electrical resistance while inducing endothelial contraction (82). They concluded that endothelial contraction alone was not necessary to impair the endothelial barrier resistance and create gaps. Subsequent papers by the same group (83, 124) and others (22) confirmed that the loss of cell-cell adhesion could cause gap formation without cell contraction. Contraction appears to increase magnitude of the gap size and contribute to the duration of the gap, although in the absence of reorganization of junction proteins it appears insufficient to induce gap formation.

Following the discovery of actomyosin, cell-cell, and cell-matrix interactions in the formation of interendothelial gaps in the 1990s, Verin and colleagues (118) completed studies addressing the pivotal role of microtubules in endothelial cell barrier integrity in 2001. Nocodazole, an agent that causes microtubule breakdown, induced interendothelial cell gaps, as well as stress fiber formation. These findings were supported in earlier work by Northover in which nocodazole increased small intestine microvessel filtration (86). In fact, Northover theorized that tensegrity could explain why nocodazole increased microvascular filtration. These two articles confirmed that microtubules were instrumental for the barrier function of the endothelium and also illustrated the necessary functional coupling between two key cytoskeletal elements that control cell shape: microtubules and actin. The nature of this interaction and the signaling intermediates that regulate it remain important areas of study today.

Separating microtubules from the actin cytoskeleton in control of cell shape has been a difficult task, as the molecular interactions between microtubules and actin are extensive, yet still poorly understood. However, study of bacterial toxins has revealed a mechanism of gap formation that appears to disassemble microtubules without concomitantly inducing stress fibers. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin Y (ExoY) is a soluble adenylyl cyclase that is introduced into mammalian cells through a type III secretion system (129). It acquires adenylyl cyclase activity upon binding a mammalian cofactor and generates cAMP within a microtubule-rich subcellular domain (101). The cAMP generated by ExoY causes nonneuronal tau phosphorylation (100), which parallels microtubule disassembly. A mammalian chimeric soluble adenylyl cyclase (sACI/II) has similar activity (95). sACI/II generates cAMP that disassembles microtubules, induces interendothelial cell gaps, and increases permeability, yet fails to increase myosin light chain phosphorylation and induce stress fibers (95). Exactly how the disassembly of peripheral microtubules induces gaps remains unknown, but the actions of these soluble adenylyl cyclases clearly indicate that a gap can form in the absence of frank cellular contraction.

Evidence suggests that endothelial cell gap formation is a physiological process that is highly dynamic in nature. During the 1990s, McDonald and collaborators (6, 46, 76) presented data that revealed the dynamic nature of gap formation and resealing (Fig. 5) and suggested that the formation of interendothelial cell gaps is a transient process that does not necessarily impair endothelial cell behavior. By combining scanning electron microscopy and silver nitrate staining, this group analyzed substance P-dependent endothelial cell gap formation in rat trachea. They identified the order of events resulting in gap formation that accompanied plasma leakage. They found heterogeneity in gap structure, with evidence for one pore, multiple pores, and oblique gaps. They proposed that these events were a continuum of morphological changes at the endothelial borders associated with the opening and closing of endothelial gaps. According to them, following an inflammatory stimulus, gaps with multiple pores form first. Subsequently, pores in the gaps start to close and interendothelial cell gaps containing a single pore are detected, accompanied by an oblique gap. These studies were critical to confirm the existence of gaps, since several investigators have questioned the importance of them, arguing that Majno's observation had been misinterpreted (23, 33, 43). Indeed, McDonald and colleagues data indicate that gap formation is a physiologically important, dynamic process (opening and then closing) throughout the inflammatory process.

Fig. 5.

A: silver lines marking the borders of endothelial cells in normal venules. B: silver lines of endothelial cells by scanning electron microscopy at higher magnification. C: silver deposits and gaps (arrows) in venular endothelial cells after substance P treatment. D: gaps formed in endothelial cells after substance P treatment by scanning electron microscopy at higher magnification. [From original figures published by Hirata et al. (46).]

Studies on the Lung Endothelium

Lung biologists have contributed greatly to our understanding of both the physiological significance and molecular complexities of endothelial cell gap formation. Because the pulmonary circulation is not easily accessible, deciphering what to measure was a principal historical hurdle to the study of lung endothelial barrier properties. Development of an approach to measure lymphatics that drain the pulmonary circulation was a tremendous advance, because the flow volume and protein composition of lymphatic fluid could be quantified (64, 115). Increases in lymphatic flow were then related to the evolution of two prominent findings in pulmonary edema: perivascular cuffs and alveolar flooding. Studies using a variety of insults, including elevated left atrial pressure (44, 116), elevated pulmonary arterial pressure (123), hypoxia and exercise (73, 123), chemical toxins (94), inflammatory agents (93), and bacteria or bacterial products (13, 14) have documented how increased lymphatic flow related in time to perivascular cuffing and development of alveolar flooding.

In a classic Physiological Reviews paper (107), Staub amalgamated findings from multiple laboratories that used various assessment methods into a functional working model of pulmonary edema, a model that has remained essentially intact to this day. In this model, increased fluid, solute, and protein flux across the endothelial cell barrier initially accesses the loose interstitial spaces, where it is drawn by negative interstitial pressure into perivascular cuffs, making the fluid, solutes, and protein accessible to lymphatics for drainage. Physiologically meaningful filtration is thought to occur across capillaries, because of the enormous capillary surface area compared with the pre- or postcapillary conduit vessel surface area. Alveolar flooding is believed to occur only in circumstances where the rate of fluid filtration exceeds the lung's safety factors against edema formation, which include increased interstitial pressure, decreased interstitial protein concentration, and increased lymph flow, and in circumstances in which the alveolar epithelial barrier is injured.

Staub was aware that this general model did not adequately describe all of the experimental results. He was intrigued by a contrast in the results of Schneeberger et al. (102) and Pietra and coworkers (94). Schneeberger's group utilized horseradish peroxidase (HRP; molecular mass ≈ 40 kDa) to track protein exudation in lung. Schneeberger documented HRP leakage through the intercellular junctions of capillary endothelial cells. In a follow-up to this initial study, no such HRP leakage was observed in adult lungs, and only modest junctional permeability was noted across the pulmonary capillary endothelial cell cleft in neonatal rats. In contrast, Pietra and coworkers did not observe any increase in HRP tracer extravasation under normal left atrial pressures. HRP penetrated the junctions when left atrial pressure was increased to 30 mmHg, but it did not enter the alveolar spaces until left atrial pressure was increased to 70 mmHg. The paradox in these data is that extensive evidence had shown normal lung lymph contains high plasma protein concentrations, suggesting that proteins leak through capillaries at normal physiological pressures; yet HRP extravasation could not be observed under normal physiological pressures. Staub considered two possibilities in explaining this paradox: “One possibility is that the time course of the experiments was too short and the sensitivity of the method too low for small concentrations of tracers to be detected. A second possibility is that the normal fluid and protein leakage site may not be the capillaries” (Ref. 107, p. 766).

In this latter point, Staub considers a concept at odds with the general belief that conduit and resistance vessels do not meaningfully contribute to fluid, solute, and protein flux because of their trivial surface exchange area. Although it was not a generally accepted concept at the time, indirect evidence from several laboratories provided evidence that extra-alveolar vessels contribute to pulmonary edema. Bohm's studies suggested that pulmonary venule endothelial cells were more sensitive to an endothelial cell poison, α-naphthylthiourea (ANTU), than were capillary endothelial cells (12). Meyrick and Reid did not similarly conclude that ANTU's effects were more selective at the postcapillary site, but they identified that ANTU caused interstitial edema before any evidence of capillary injury (80). Findings from Whayne and Severinghaus (123) and Iliff (47) were also suggestive that noncapillary segments could contribute to pulmonary edema, yet no unifying theme emerged to explain how this might happen.

Recently, the use of thapsigargin has shed novel insight into how extra-alveolar vessels contribute to pulmonary edema. Thapsigargin is a plant alkaloid commonly used to activate calcium entry through store operated calcium entry channels. Thapsigargin dose dependently increases the filtration coefficient in isolated perfused lungs. Histological assessment following treatment reveals perivascular fluid cuffs surrounding arteries and veins, with no evidence of alveolar flooding (17). Electron microscopy studies support these biophysical and histological assessments, as interendothelial cell gaps are observed in pulmonary artery and vein segments, with interstitial thickening between smooth muscle cells, whereas gaps are not seen in endothelial cells within the capillary segment. Thapsigargin infusion in intact animals similarly increases extra-alveolar edema without causing alveolar flooding (66). Thus thapsigargin can induce interendothelial cell gaps in extra-alveolar segments, which cause fluid to accumulate in perivascular cuffs without causing alveolar flooding.

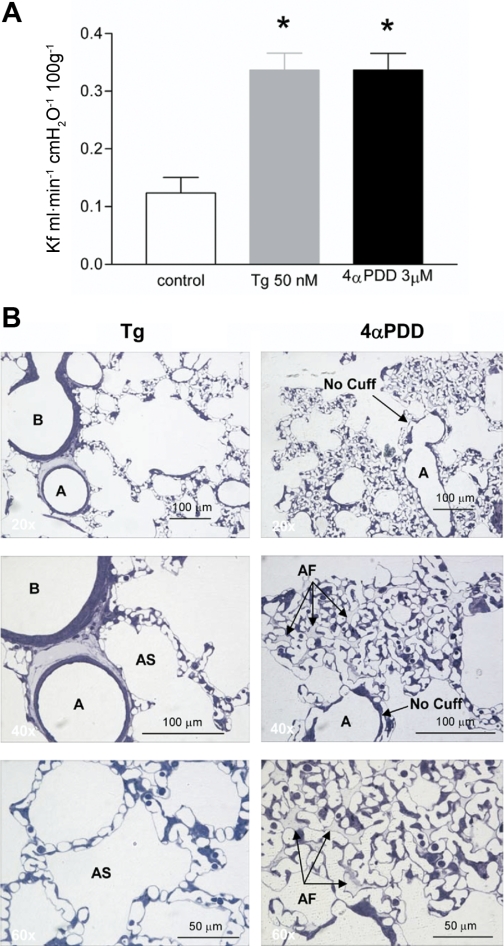

The strength of these observations using thapsigargin is bolstered by parallel studies using a second agonist, 4α-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (4αPDD). 4αPDD infusion increases the filtration coefficient in isolated perfused lungs, just like thapsigargin (5, 66). However, unlike thapsigargin, 4αPDD does not induce perivascular cuffing, certainly not to the extent seen with thapsigargin. Rather, 4αPDD induces alveolar edema (Fig. 6). The mechanism of 4αPDD action remains incompletely understood; whereas thapsigargin induces interendothelial cell gaps, 4αPDD-induced gaps have not yet been observed. 4αPDD appears to induce sloughing, or a loss of cell-matrix tethering, principally within the capillary segment. These observations do not fit the working model of pulmonary edema evolution, because with 4αPDD water is not drawn into perivascular cuffs as a safety factor prior to alveolar flooding. Other previously unappreciated safety factors must exist and be considered.

Fig. 6.

A: pulmonary vascular permeability of thapsigargin (Tg)- and 4α-phorbol 12,13-didecanoate (4αPDD)-treated lungs. B, left: Tg-treated lungs show perivascular cuffing and no alveolar flooding. Right: in contrast to Tg treatment, 4αPDD-treated lungs demonstrated alveolar flooding without perivascular cuffing. [From original figures published by Lowe et al. (66).]

Seminal studies by Staub and Taylor identified the vascular barrier as a one of various safety factors against edema formation in the lung (see references in Refs. 32 and 89). They reached their conclusions while considering the lung endothelium as a homogenous cell layer, which was the established dogma at the time. Today, however, there is a growing awareness that endothelium is not a homogeneous cell layer, but rather a heterogeneous one, with phenotypic heterogeneity apparent along the arterial-capillary-venous segments (1, 109). This heterogeneity is true even among vascular segments of continuous type endothelium. (40, 112). One of the unique features of lung capillary endothelium is that it possesses a highly restrictive barrier, especially when compared with extra-alveolar endothelium (87, 89, 96, 110, 111). Recently, Parker (89) and Effros and Parker (32) have addressed this important issue. On the basis of empirical evidence, they propose that the intrinsically restrictive barrier of capillary endothelium is the single most important safety factor against alveolar flooding.

If true, then the comparison between thapsigargin- and 4αPDD-induced pulmonary edema is important for four reasons. First, the data illustrate that increased permeability across extra-alveolar endothelium can result in pulmonary edema that is restricted to perivascular tissue spaces, an effect that reduces lung compliance (67); this does not mean that the fluid in perivascular spaces are not eventually capable of reaching the alveolar air spaces. Second, alveolar flooding can occur in the absence of perivascular cuffing, meaning that perivascular cuffing is not an absolute prerequisite to alveolar flooding; water, solutes, and proteins can directly access the alveolar space. Third, the capillary endothelial cell barrier is uniquely restrictive among other lung endothelial cell types and in this capacity serves as a critical safety factor against alveolar edema that must be included with the other safety factors traditionally recognized. Fourth, extra-alveolar and capillary endothelium a represent phenotypically distinct cell types, which uniquely interpret their chemical and biomechanical environments in control of barrier function. Capillary endothelial cells are not prone to generating interendothelial cell gaps, likely because of their restrictive barrier. When these cells do generate interendothelial cell gaps, they are rapidly resealed due to intrinsically rapid migration (18) and proliferation rates of this cell type (4, 91). Indeed, the lung's capillary endothelium represents a highly specialized cell type whose function it is to protect the fidelity of the alveolar-capillary membrane.

Conclusion

By the beginning of this century, it was clear that inflammatory mediators induce interendothelial cell gaps as an essential mechanism for regulating paracellular permeability, that in many vascular beds of the systemic circulation gaps occur principally in venules, and that the endothelial cytoskeleton, primarily actin and microtubules acting in concert with cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesions, dynamically reorganizes to enable gap formation. This collection of work represents remarkable progress over the past 50 years in a field that began in the first century AD, with efforts to understand the hallmarks of inflammation (pain, redness, heat, and swelling) as described by Celsus (57).

Despite these advances, there are still questions of colossal importance that need to be answered. In particular, how do the dynamics of endothelial cell gap formation differ among vascular beds and/or within the same organ system? In this regard, we have begun to investigate the nature of interendothelial gaps that form within the pulmonary circulation. The nature of these interendothelial gaps is indeed different in conduit vessels vs. in capillaries, and whereas pulmonary artery endothelial cells readily form gaps in response to permeability-increasing compounds, lung capillaries under the same circumstances do not. In fact, lung capillary endothelial cells form an incredibly tight vascular barrier (32, 89); one of their most treasured cellular attributes, still poorly understood, is how they can form such an incredibly resistant barrier while having an anatomically limited junction. Nevertheless, published observations demonstrate, both in vivo and in vitro, that the endothelial cells forming lung capillaries clearly form reversible gaps (18, 101, 125).

Insight into the cell biology of endothelial cell gap formation remains rudimentary. Gaining deeper insight into this process will narrow the distance between the bench and the bedside, particularly relevant to the study of diseases like sepsis and acute respiratory distress syndrome (120), pathologies in which vascular leak and interendothelial cell gaps play a key role in their pathogenesis, so patients suffering from these diseases can benefit from over a century of active biomedical research (Table 1).

Table 1.

Resolving the interendothelial cell gap timeline

| 1873. Cohnheim proposes that the primary cause of pus formation was a “molecular impairment” of the walls of the vessels. |

| 1910–1919. Dale discovers histamine and its effect in the vasculature. |

| 1921. Lewis finds that injured tissues produce histamine-like substances. |

| 1940. Chambers proposes the existence of intercellular cement that holds endothelial cells together. He finds that the integrity of this cement depends on Ca2+ and pH. |

| 1948. Rapport et al. discover serotonin. |

| 1949. Rocha e Silva et al. discover bradykinin. |

| 1961. Majno and Palade use transmission electron microscopy and find that histamine and serotonin induce interendothelial gaps in postcapillary venules. |

| 1963. Murayama first attempt to isolate human endothelial cells. |

| 1969. Majno proposes that endothelial cell contraction is responsible for interendothelial gap formation. |

| 1973. Jaffe and Nachman unequivocally isolate human endothelial cells and characterize them morphologically as well as immunohistochemically. |

| 1973. McDonald reports that thrombin “rounds up” endothelial cells. |

| 1975. Lauwereyns identifies actin bundles after treating endothelial cells with meromyosin. |

| 1982. Shasby presents evidence for an active role of the cytoskeleton in interendothelial gap formation. |

| 1986. Malik's group report the link between thrombin-induced interendothelial cell gaps and increased permeability. |

| 1990–1992. Wysolmerski confirms that endothelial cells contract. |

| 1992. Dejana and colleagues discover vascular-endothelial cadherin. |

| 1993. Ingber advances the theory of tensegrity as the cytoskeletal basis for cell shape and cell shape change. |

| 1995–1999. McDonald and collaborators use scanning electron microscopy to resolve that interendothelial gaps are a dynamic event. |

| 1996–1999. Moy and Winter propose that the cellular tensegrity theory could explain interendothelial gap formation. |

| 1997. Garcia and colleagues clone a unique “endothelial cell” myosin light chain kinase. |

| 2001. Verin confirms that microtubules play a critical role in interendothelial gap formation. |

| 2004-2008. Soluble cyclases disassemble microtubules without causing frank cell contraction. |

GRANTS

T. Stevens was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R37HL060024 and P01HL066299. C. D. Ochoa was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32HL076125 and F31HL10712.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the author(s).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Drs. Ivan F. McMurtry and Donna L. Cioffi for helpful criticism of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Aird W. Mechanisms of endothelial cell heterogeneity in health and disease. Circ Res 98: 159–162, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alexander JS, Hechtman HB, Shepro D. Phalloidin enhances endothelial barrier function and reduces inflammatory permeability in vitro. Microvasc Res 35: 308–315, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alksne JF. The passage of colloidal particles across the dermal capillary wall under the influence of histamine. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 44: 51–66, 1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez DF, Huang L, King JA, ElZarrad MK, Yoder MC, Stevens T. Lung microvascular endothelium is enriched with progenitor cells that exhibit vasculogenic capacity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 294: L419–L430, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Alvarez DF, King JA, Weber D, Addison E, Liedtke W, Townsley MI. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4-mediated disruption of the alveolar septal barrier: a novel mechanism of acute lung injury. Circ Res 99: 988–995, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baluk P, Hirata A, Thurston G, Fujiwara T, Neal CR, Michel CC, McDonald DM. Endothelial gaps: time course of formation and closure in inflamed venules of rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 272: L155–L170, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Becker CG, Murphy GE. Demonstration of contractile protein in endothelium and cells of the heart valves, endocardium, intima, arteriosclerotic plaques, and Aschoff bodies of rheumatic heart disease. Am J Pathol 55: 1–37, 1969 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Becker CG, Nachman RL. Contractile proteins of endothelial cells, platelets and smooth muscle. Am J Pathol 71: 1–22, 1973 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhattacharya J. Hydraulic conductivity of lung venules determined by split-drop technique. J Appl Physiol 64: 2562–2567, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bhattacharya J, Staub NC. Direct measurement of microvascular pressures in the isolated perfused dog lung. Science 210: 327–328, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birmingham K. Judah Folkman. Nat Med 8: 1052, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bohm GM. Vascular permeability changes during experimentally produced pulmonary oedema in rats. J Pathol Bacteriol 92: 151–161, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brigham KL, Owen PJ, Bowers RE. Increased permeability of sheep lung vessels to proteins after Pseudomonas bacteremia. Microvasc Res 11: 415–419, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brigham KL, Woolverton WC, Blake LH, Staub NC. Increased sheep lung vascular permeability caused by pseudomonas bacteremia. J Clin Invest 54: 792–804, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chambers R, Zweifach BW. Intercellular cement and capillary permeability. Physiol Rev 947: 436–463, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chambers R, Zweifach BW. Capillary endothelial cement in relation to permeability. J Cell Comp Physiol 15: 255–272, 1940 [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chetham PM, Babál P, Bridges JP, Moore TM, Stevens T. Segmental regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability by store-operated Ca2+ entry. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 276: L41–L50, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cioffi DL, Moore TM, Schaack J, Creighton JR, Cooper DM, Stevens T. Dominant regulation of interendothelial cell gap formation by calcium-inhibited type 6 adenylyl cyclase. J Cell Biol 157: 1267–1278, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohnheim J. Inflammation. In: Lectures on General Pathology. A Handbook for Practitioners and Students. The Pathology of the Circulation, translated by McKee AB. Leipzig, Germany: The New Sydenham Society, 1889, vol. 1, chapt. 5, p. 242–382 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corada M, Mariotti M, Thurston G, Smith K, Kunkel R, Brockhaus M, Lampugnani MG, Martin-Padura I, Stoppacciaro A, Ruco L, McDonald DM, Ward PA, Dejana E. Vascular endothelial-cadherin is an important determinant of microvascular integrity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 9815–9820, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Curry FE, Adamson RH. Transendothelial pathways in venular microvessels exposed to agents which increase permeability: the gaps in our knowledge. Microcirculation 6: 3–5, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curry FE, Michel CC. A fiber matrix model of capillary permeability. Microvasc Res 20: 96–99, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. Histamine shock. J Physiol 52: 355–390, 1919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dale HH, Laidlaw PP. The physiological action of beta-iminazolylethylamine. J Physiol 41: 318–344, 1910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dale HH, Richards AN. The vasodilator action of histamine and of some other substances. J Physiol 52: 110–165, 1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Danielli JF. Capillary permeability and oedema in the perfused frog. J Physiol 98: 109–129, 1940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Darwin F. On the primary vascular dilatation in acute inflammation. J Anat Physiol 10: 1–16, 1875 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dejana E, Corada M, Lampugnani MG. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions. FASEB J 9: 910–918, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol 91: 1487–1500, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Effros RM, Parker JC. Pulmonary vascular heterogeneity and the Starling hypothesis. Microvasc Res 78: 71–77, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Feng D, Nagy JA, Hipp J, Pyne K, Dvorak HF, Dvorak AM. Reinterpretation of endothelial cell gaps induced by vasoactive mediators in guinea-pig, mouse and rat: many are transcellular pores. J Physiol 504: 747–761, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Fryer DG, Birnbaum G, Luttrell CN. Human endothelium in cell culture. J Atheroscler Res 6: 151–163, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fye WB. Profiles in cardiology. Julius Friedrich Cohnheim. Clin Cardiol 25: 575–577, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Garcia JG. Concepts in microvascular endothelial barrier regulation in health and disease. Microvasc Res 77: 1–3, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garcia JG, Davis HW, Patterson CE. Regulation of endothelial cell gap formation and barrier dysfunction: role of myosin light chain phosphorylation. J Cell Physiol 163: 510–522, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Garcia JG, Lazar V, Gilbert-McClain LI, Gallagher PJ, Verin AD. Myosin light chain kinase in endothelium: molecular cloning and regulation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 16: 489–494, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Garcia JG, Siflinger-Birnboim A, Bizios R, Del Vecchio PJ, Fenton JW, 2nd, Malik AB. Thrombin-induced increase in albumin permeability across the endothelium. J Cell Physiol 128: 96–104, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gebb S, Stevens T. On lung endothelial cell heterogeneity. Microvasc Res 68: 1–12, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giacomelly F, Wiener J, Spiro D. Cross-striated arrays of filaments in endothelium. J Cell Biol 45: 188–192, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gimbrone MA, Jr, Cotran RS, Folkman J. Human vascular endothelial cells in culture. Growth and DNA synthesis. J Cell Biol 60: 673–684, 1974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Grega JG, Adamski SW, Svensjo E. Is there evidence for the venular large junctional gap formation in inflammation? Microcirc Endothelium Lymphatics 2: 211–233, 1985 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guyton AC, Lindsey AW. Effect of elevated left atrial pressure and decreased plasma protein concentration on the development of pulmonary edema. Circ Res 7: 649–657, 1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Henriksen T, Evensen SA, Elgjo RF, Vefling A. Human fetal endothelial cells in cluture. Scand J Haematol 14: 233–241, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hirata A, Baluk P, Fujiwara T, McDonald DM. Location of focal silver staining at endothelial gaps in inflamed venules examined by scanning electron microscopy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 269: L403–L418, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Iliff LD. Extra-alveolar vessels and oedema development in excised dog lungs. J Physiol 207: 85P–86P, 1970 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ingber DE. Cellular tensegrity: defining new rules of biological design that govern the cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci 104: 613–627, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jacobson JR, Garcia JG. Novel therapies for microvascular permeability in sepsis. Curr Drug Targets 8: 509–514, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jaffe EA, Hoyer LW, Nachman RL. Synthesis of antihemophilic factor antigen by cultured human endothelial cells. J Clin Invest 52: 2757–2764, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jaffe EA, Nachman RL, Becker CG, Minick CR. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins. Identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Invest 52: 2745–2756, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kolodney MS, Wysolmerski RB. Isometric contraction by fibroblasts and endothelial cells in tissue culture: a quantitative study. J Cell Biol 117: 73–82, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krogh A. Nobel Lecture in Physiology or Medicine: A contribution to the physiology of the capillaries [Online]. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1920/krogh-lecture.html [11 Sept. 2008]

- 54.Krogh A. Studies on the physiology of capillaries: II. The reactions to local stimuli of the blood-vessels in the skin and web of the frog. J Physiol 55: 412–422, 1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Krogh A, Harrop GA, Rehberg PB. Studies on the physiology of capillaries: III. The innervation of the blood vessels in the hind legs of the frog. J Physiol 56: 179–189, 1922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kuebler WM, Ying X, Singh B, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Pressure is proinflammatory in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest 104: 495–502, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Acute and chronic inflammation. In: Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, edited by Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders, 2010, chapt. 2, p. 43–78 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lampugnani MG, Resnati M, Raiteri M, Pigott R, Pisacane A, Houen G, Ruco LP, Dejana E. A novel endothelial-specific membrane protein is a marker of cell-cell contacts. J Cell Biol 118: 1511–1522, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Landis EM. Micro-injection studies of capillary permeability: II. The relation between capillary pressure and the rate at which fluid passes through the walls of single capillaries. Am J Physiol 82: 217–238, 1927 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Landis EM. The capillary pressure in frog mesentery as determined by microinjection methods. Am J Physiol 75: 548–570, 1926 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Laposata M, Dovnarsky DK, Shin HS. Thrombin-induced gap formation in confluent endothelial cell monolayers in vitro. Blood 62: 549–556, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lauweryns JM, Baert J, De Loecker W. Intracytoplasmic filaments in pulmonary lymphatic endothelial cells. Fine structure and reaction after heavy meromyosin incubation. Cell Tissue Res 163: 111–124, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lee WL, Slutsky AS. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N Engl J Med 363: 689–691, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Leeds SE, Uhley HN, Sampson JJ, Friedman M. A new method for measurement of lymph flow from the right duct in the dog. Am J Surg 98: 211–216, 1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lewis T, Grant RT. Vascular reactions of the skin to injury. Part II. The liberation of a histamine-like substance in injured skin; the underlying cause of factitious urticaria and of wheals produced by burning; and observations upon the nervous control of certain skin reactions. Heart 11: 209–265, 1921 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lowe K, Alvarez D, King J, Stevens T. Phenotypic heterogeneity in lung capillary and extra-alveolar endothelial cells. Increased extra-alveolar endothelial permeability is sufficient to decrease compliance. J Surg Res 143: 70–77, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lowe K, Alvarez DF, King JA, Stevens T. Perivascular fluid cuffs decrease lung compliance by increasing tissue resistance. Crit Care Med 38: 1458–1466, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lum H, Malik AB. Regulation of vascular endothelial barrier function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 267: L223–L241, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Majno G, Gilmore V, Leventhal M. On the mechanism of vascular leakage caused by histaminetype mediators. A microscopic study in vivo. Circ Res 21: 833–847, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Majno G, Palade GE. Studies on inflammation. I. The effect of histamine and serotonin on vascular permeability: an electron microscopic study. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 11: 571–605, 1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Majno G, Palade GE, Schoefl GI. Studies on inflammation. II. The site of action of histamine and serotonin along the vascular tree: a topographic study. J Biophys Biochem Cytol 11: 607–626, 1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Majno G, Shea SM, Leventhal M. Endothelial contraction induced by histamine-type mediators: an electron microscopic study. J Cell Biol 42: 647–672, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Marshall BE, Teichner RL, Kallos T, Sugerman HJ, Wyche MQ, Jr, Tantum KR. Effects of posture and exercise on the pulmonary extravascular water volume in man. J Appl Physiol 31: 375–379, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Matoltsy AG, Matoltsy M. The action of histamine and antihistaminic substances on the endothelial cells of the small capillaries in the skin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 102: 237–249, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Matthay MA, Folkesson HG, Clerici C. Lung epithelial fluid transport and the resolution of pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev 82: 569–600, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. McDonald DM, Thurston G, Baluk P. Endothelial gaps as sites for plasma leakage in inflammation. Microcirculation 6: 7–22, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McDonald RI, Shepro D, Rosenthal M, Booyse FM. Properties of cultured endothelial cells. Ser Haematol 6: 469–478, 1973 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev 86: 279–367, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Mendel LB. Professor Rudolph Heidenhain. Science 6: 645–648, 1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Meyrick B, Miller J, Reid L. Pulmonary oedema induced by ANTU, or by high or low oxygen concentrations in rat—an electron microscopic study. Br J Exp Pathol 53: 347–358, 1972 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Michel CC, Curry FE. Microvascular permeability. Physiol Rev 79: 703–761, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Moy AB, Van Engelenhoven J, Bodmer J, Kamath J, Keese C, Giaever I, Shasby S, Shasby DM. Histamine and thrombin modulate endothelial focal adhesion through centripetal and centrifugal forces. J Clin Invest 97: 1020–1027, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Moy AB, Winter M, Kamath A, Blackwell K, Reyes G, Giaever I, Keese C, Shasby DM. Histamine alters endothelial barrier function at cell-cell and cell-matrix sites. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 278: L888–L898, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Maruyama Y. The human endothelial cell in tissue culture. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 60: 69–79, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Nachman RL, Jaffe EA. Endothelial cell culture: beginnings of modern vascular biology. J Clin Invest 114: 1037–1040, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Northover AM, Northover BJ. Possible involvement of microtubules in platelet-activating factor-induced increases in microvascular permeability in vitro. Inflammation 17: 633–639, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Ofori-Acquah SF, King J, Voelkel N, Schaphorst KL, Stevens T. Heterogeneity of barrier function in the lung reflects diversity in endothelial cell junctions. Microvasc Res 75: 391–402, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Pappenheimer JR, Renkin EM, Borrero LM. Filtration, diffusion and molecular sieving through peripheral capillary membranes; a contribution to the pore theory of capillary permeability. Am J Physiol 167: 13–46, 1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Parker JC, Stevens T, Randall J, Weber DS, King JA. Hydraulic conductance of pulmonary microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 291: L30–L37, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Parker JC, Townsley MI, Rippe B, Taylor AE, Thigpen J. Increased microvascular permeability in dog lungs due to high peak airway pressures. J Appl Physiol 57: 1809–1816, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Parra-Bonilla G, Alvarez DF, Al-Mehdi AB, Alexeyev M, Stevens T. Critical role for lactate dehydrogenase a in aerobic glycolysis that sustains pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 299: (4) L513–L522, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Partridge CA, Horvath CJ, Del Vecchio PJ, Phillips PG, Malik AB. Influence of extracellular matrix in tumor necrosis factor-induced increase in endothelial permeability. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 263: L627–L633, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Pietra GG, Szidon JP, Leventhal MM, Fishman AP. Histamine and interstitial pulmonary edema in the dog. Circ Res 29: 323–337, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Pietra GG, Szidon JP, Leventhal MM, Fishman AP. Hemoglobin as a tracer in hemodynamic pulmonary edema. Science 166: 1643–1646, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Prasain N, Alexeyev M, Balczon R, Stevens T. Soluble adenylyl cyclase-dependent microtubule disassembly reveals a novel mechanism of endothelial cell retraction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L73–L83, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Prasain N, Stevens T. The actin cytoskeleton in endothelial cell phenotypes. Microvasc Res 77: 53–63, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Rapport MM, Green AA, Page IH. Crystalline serotonin. Science 108: 329–330, 1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Rocha e Silva M, Beraldo WT, Rosenfeld G. Bradykinin, a hypotensive and smooth muscle stimulating factor released from plasma globulin by snake venoms and by trypsin. Am J Physiol 156: 261–273, 1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Ryan US, Clements E, Habliston D, Ryan JW. Isolation and culture of pulmonary artery endothelial cells. Tissue Cell 10: 535–554, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sayner SL, Balczon R, Frank DW, Cooper DM, Stevens T. Filamin A is a phosphorylation target of plasma membrane but not cytosolic adenylyl cyclase activity. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L117–L124, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Sayner SL, Frank DW, King J, Chen H, VandeWaa J, Stevens T. Paradoxical cAMP-induced lung endothelial hyperpermeability revealed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoY. Circ Res 95: 196–203, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Schneeberger EE, Karnovsky MJ. The influence of intravascular fluid volume on the permeability of newborn and adult mouse lungs to ultrastructural protein tracers. J Cell Biol 49: 319–334, 1971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Schwann T. Capillary vessels. In: Microscopical Researches into the Accordance in the Structure and Growth of Animals and Plants, translated by Smith H. London: The Sydenham Society, 1847, p. 154–160 [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shasby DM, Shasby SS, Sullivan JM, Peach MJ. Role of endothelial cell cytoskeleton in control of endothelial permeability. Circ Res 51: 657–661, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Shepard JM, Goderie SK, Brzyski N, Del Vecchio PJ, Malik AB, Kimelberg HK. Effects of alterations in endothelial cell volume on transendothelial albumin permeability. J Cell Physiol 133: 389–394, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Starling EH. On the absorption of fluids from the connective tissue spaces. J Physiol 19: 312–326, 1896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Staub NC. Pulmonary edema. Physiol Rev 54: 678–811, 1974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Staub NC, Nagano H, Pearce ML. Pulmonary edema in dogs, especially the sequence of fluid accumulation in lungs. J Appl Physiol 22: 227–240, 1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Stevens T. Molecular and cellular determinants of lung endothelial cell heterogeneity. Chest 128: 558S–564S, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Stevens T. Microheterogeneity of lung endothelium. In: Endothelial Biomedicine, edited by Aird WC. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2007, chapt. 126, p. 1161–1177 [Google Scholar]

- 111.Stevens T, Phan S, Frid MG, Alvarez D, Herzog E, Stenmark KR. Lung vascular cell heterogeneity: endothelium, smooth muscle, and fibroblasts. Proc Am Thorac Soc 5: 783–791, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Stevens T, Rosenberg R, Aird W, Quertermous T, Johnson FL, Garcia JG, Hebbel RP, Tuder RM, Garfinkel S. NHLBI workshop report: endothelial cell phenotypes in heart, lung, and blood diseases. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C1422–C1433, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Taylor AE, Gaar KA., Jr Estimation of equivalent pore radii of pulmonary capillary and alveolar membranes. Am J Physiol 218: 1133–1140, 1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Todd R, Bowman W. The circulation of the blood. In: The Physiological Anatomy and Physiology of Man. London: Blanchard and Lea, 1857, chapt. 28, p. 649–654 [Google Scholar]

- 115.Uhley H, Leeds SE, Sampson JJ, Friedman M. Some observations on the role of the lymphatics in experimental acute pulmonary edema. Circ Res 9: 688–693, 1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Uhley HN, Leeds SE, Sampson JJ, Friedman M. Role of pulmonary lymphatics in chronic pulmonary edema. Circ Res 11: 966–970, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Van Arsdale WI. Landerer's mechanical theory of inflammation. Ann Surg 2: 479–485, 1885 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Verin AD, Birukova A, Wang P, Liu F, Becker P, Birukov K, Garcia JG. Microtubule disassembly increases endothelial cell barrier dysfunction: role of MLC phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L565–L574, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 260: 1124–1127, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1334–1349, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Watterson DM, Collinge M, Lukas TJ, Van Eldik LJ, Birukov KG, Stepanova OV, Shirinsky VP. Multiple gene products are produced from a novel protein kinase transcription region. FEBS Lett 373: 217–220, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Wells WA. How vessels become leaky. J Cell Biol 168: 677–677, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 123. Whayne TF, Jr, Severinghaus JW. Experimental hypoxic pulmonary edema in the rat. J Appl Physiol 25: 729–732, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Winter MC, Kamath AM, Ries DR, Shasby SS, Chen YT, Shasby DM. Histamine alters cadherin-mediated sites of endothelial adhesion. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L988–L995, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Wu S, Cioffi EA, Alvarez D, Sayner SL, Chen H, Cioffi DL, King J, Creighton JR, Townsley M, Goodman SR, Stevens T. Essential role of a Ca2+-selective, store-operated current (ISOC) in endothelial cell permeability: determinants of the vascular leak site. Circ Res 96: 856–863, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Regulation of permeabilized endothelial cell retraction by myosin phosphorylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 261: C32–C40, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Involvement of myosin light-chain kinase in endothelial cell retraction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 16–20, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Wysolmerski RB, Lagunoff D. Inhibition of endothelial cell retraction by ATP depletion. Am J Pathol 132: 28–37, 1988 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Yahr TL, Vallis AJ, Hancock MK, Barbieri JT, Frank DW. ExoY, an adenylate cyclase secreted by the Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 13899–13904, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]