Abstract

Prostatic adenocarcinomas are reliant on androgen receptor (AR) activity for survival and progression. Therefore, first-line therapeutic intervention for disseminated disease entails the use of AR-directed therapeutics, achieved through androgen deprivation and direct AR antagonists. While initially effective, recurrent, ‘castrate-resistant’ prostate cancers arise, for which there is no durable means of treatment. An abundance of clinical study and preclinical modeling has led to the revelation that restored AR activity is a major driver of therapeutic failure and castrate-resistant prostate cancer development. The mechanisms underpinning AR reactivation have been identified, providing the foundation for a new era of drug discovery and rapid translation into the clinic. As will be reviewed in this article, these creative new ways of suppressing AR show early promise.

Keywords: abiraterone, androgen receptor, cell cycle, hormone therapy, prostatic adenocarcinoma, retinoblastoma

Prostate cancer incidence & progression

As of 2010, prostate cancer remains the most frequently diagnosed noncutaneous malignancy and a leading cause of male cancer death [1]. It is predicted that this year alone, over 217,000 men in the USA will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, and up to 32,000 will die of this disease. Given the prevalence of tumor development and morbidity associated with advanced prostate cancer, current clinical and translational challenges center on the design of new therapeutic intervention strategies that may prove effective at achieving cure. Accurate identification of tumors that remain confined to the prostate is of undeniable benefit, as this stage of disease is treatable through radical prostatectomy or radiation therapy [2–5]. Unfortunately, a significant fraction (up to 15%) of patients harbor metastatic lesions at the time of initial diagnosis [6]. Moreover, an even larger percentage will go on to fail therapy and require treatment for non-organ-confined disease. It is this disease state for which no curative treatment regimen has been identified. This state is therefore an area of intensive investigation [7,8].

Prostate cancers are dependent on androgen receptor signaling

Overview of androgen receptor regulation & function

First-line intervention for disseminated prostate cancer leverages the extraordinary dependence of prostate cancer cells on androgen receptor (AR) signaling [7,9–11]. Prostate cancers respond relatively poorly to standard cytotoxic therapies (similar to many other solid tumors), but undergo significant tumor regression when challenged with AR-directed therapeutics. At the cellular level, both cell cycle arrest and cell death are observed upon inhibition of AR activity [12], thus underscoring the impact of AR as a valid therapeutic target in advanced disease.

As a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, AR functions as a ligand-dependent transcription factor (Figure 1) that contains conserved C-terminal functional domains (hinge, DNA-binding domain and the ligand-binding domain [LBD]) but harbors a unique N-terminal region [13–17]. Unlike many of the other nuclear receptors, it is this N-terminal region that supports the main transcriptional transactivation function of the receptor (activation function 1 [AF1]). Before ligand binding, the AR is present diffusely throughout the cell and is held inactive through association with inhibitory molecules such as heat-shock proteins. Testosterone, while the most prevalent androgen in serum, can bind and activate AR, but in the context of the prostate, this androgen is generally converted though the action of 5-α reductase to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a potent androgen that is heightened in capacity to activate the receptor [18]. Ligand (testosterone or DHT) binding through the C-terminal LBD of the receptor, results in dissociation of inhibitory proteins, homodimerization of the receptor, conformational changes (including association of the receptor N- and C-termini) that promote transcriptional transactivation potential, post-translational modifications and rapid translocation of ligand-bound AR into the nucleus. These activated receptors bind to DNA at regulatory loci (promoters or enhancers) and therein elicit cell and context-dependent gene expression programs that result in variant cellular outcomes [19,20]. A subset of these binding events occur at specific DNA sequences deemed androgen-responsive elements (AREs), and study of AR function at these sites has provided a basis to dissect the molecular mechanisms of AR activity.

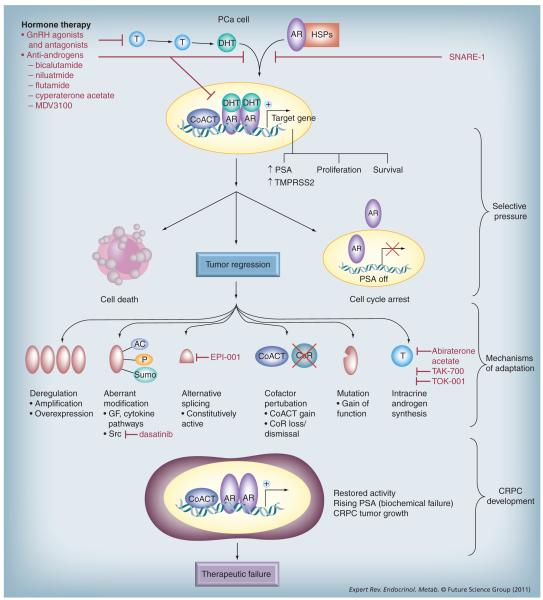

Figure 1. Mechanisms of androgen receptor reactivation in the transition to castration-resistant prostate cancer.

As discussed, tumors evade hormone therapy through restoring AR activity, which can be achieved through multiple mechanisms. Agents designed to target hormone therapy-naive and recurrent AR activity are shown in red.

AC: Acetylation; AR: Androgen receptor; CoACT: Coactivator; CoR: Corepressor; CRPC: Castration-resistant prostate cancer; DHT: Dihydrotestosterone; GF: Growth factor; GnRH: Gonadotropin-releasing hormone; HSP: Heat-shock protein; P: Phosphorylation; PSA: Prostate-specific antigen; SNARE: Soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor; Sumo: Sumolyation; T: Testosterone.

Strikingly, one of the best-characterized AR target genes encodes prostate-specific antigen (PSA) [21], a secreted protein marker used clinically to monitor prostate cancer development and progression [22,23]. Since expression of the gene encoding PSA (KLK3) is dependent on AR activity, clinical evaluation of serum PSA levels allows for metrics to identify the burden of prostate-derived cells for which the AR pathway is actively engaged. While clinically useful, there is limited evidence to suggest that the PSA protein participates in the ability of the receptor to promote tumor development or progression. Unbiased gene-expression studies and genome-wide analyses of AR function have not yet identified a single AR target that is causative for disease development or progression; rather, the current data suggest that the means by which AR promotes prostate cancer survival and proliferation is complex. For example, recent findings have revealed that AR need not utilize consensus AREs to bind to chromatin [19,20,24,25], and that the genes regulated by AR activity may be altered as a function of disease progression [19]. Also noteworthy is that common chromosomal translocations found in prostate cancer, most prominently those exemplified by the TMPRSS2–v-ets erthyroblastosis virus E2G oncogene homolog (ERG) fusions [26], may arise in part due to AR function [27,28], and place protumorigenic transcription factors (e.g., ERG, ETV1, ETV4 and ETV5) under the control of AR-dependent regulatory elements [29]. Although these translocation events alone are not typically sufficient to promote tumorigenesis in genetically engineered animal model systems [30], cooperative deregulation of AR and ERG signaling in tissue recombination systems resulted in the development of invasive adenocarcinoma [31]. Much remains to be understood with regard to identifying the minimal targets utilized by AR to induce resultant tumor phenotypes associated with proliferation, migration and invasion. Thus, while the requirement of AR activity for prostate cancer development and progression is undeniable, the means by which AR promotes formation of lethal tumor phenotypes appears to be complex and remains incompletely defined.

Targeting AR in disseminated disease

Although the impact of castration on the prostate was noted as early as the 1780s [32], landmark studies by Huggins and Hodges in the 1940s and 1970s demonstrated that androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) results in prostate cancer regression [33–35], and this overall premise has remained the underlying basis for clinical management of disseminated disease. Currently, suppression of testicular androgen synthesis (which accounts for up to 95% of serum testosterone) can be effectively achieved through utilization of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists [7]. Such strategies, which suppress AR activity through limiting access to the ligand, can be supplemented with direct AR antagonists such as bicalutamide (Casodex®), flutamide (Eulexin®) or nilutamide (Nilandron®). These AR antagonists, in combination with surgical or medical castration, may result in further AR suppression [36], although this remains controversial; investigation of long-term outcomes in patients given AR antagonists in combination with androgen deprivation revealed mixed results with regard to progression-free and overall survival [37]. The pure antagonist competes with testostorone or DHT for the AR ligand-binding domain, and consonantly dampens receptor activity through passive means. A second, actively suppressive function has also been realized, in that the receptor perceives the antagonist as a ligand that promotes nuclear entry and DNA binding; however, once bound to DNA, bicalutamide-bound receptors can induce recruitment of corepressor molecules such as nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) and SMRT (or NCoR 2) to actively suppress transcriptional transactivation [38]. As would be expected, effective AR targeting typically results in both suppression of detectable serum PSA, cancer-related symptoms and tumor regression. While the vast majority of tumors respond in kind to these common AR-directed therapeutics regimens [7], the responses are transient. Within a median time period of only 2–3 years, recurrent ‘castration-resistant’ prostate cancers (CRPCs) evolve for which only a limited set of noncurative therapeutic options are available. Docetaxel, a microtubule-binding chemotherapeutic, was approved in 2004 for use in CRPC and has been shown to confer modest survival advantage to patients [39,40]. More recently, additional therapies such as cabazitaxel, a novel microtubule inhibitor, and an immunotherapy-based vaccine called sipulcel-T have shown some clinical benefit in patients who have failed first-line docetaxel chemotherapy [41,42]. Clearly, a better understanding of the mechanisms that give rise to CRPC and development of means to delay or prevent this process are urgently needed. Although multiple means exist through which CRPC cells evade AR-directed therapeutics, robust clinical and laboratory investigations support the postulate that incurable CRPC arises as a result of failure to control recurrent AR activity.

Recurrent AR activity & CRPC: many roads converge to a common end

Resurgent AR can promote CRPC formation, and has been shown in model systems to be both causative and sufficient for transition to this lethal form of disease [7,11]. In the clinic, radiographic evidence of recurrent tumor formation is almost invariably heralded by a preceding rise in PSA, indicating that AR has been aberrantly reactivated despite the maintenance of ADT or combined androgen blockade. More recent studies have validated this point, in that a large number of AR target genes are induced in clinical CPRC. In the laboratory setting, transformative studies by Sawyers and colleagues demonstrated, using xenograft models of human disease, that resurgent AR activity after castration of the murine host is sufficient to confer aggressive CRPC growth in vivo [43]. Based on these and concurrent observations, it was hypothesized that ADT exerts selective pressure for the formation of new paths to restore AR signaling, and that discerning the underpinning mechanism(s) of recurrent AR activity may provide means for the development of new rationally devised nodes of therapeutic intervention. As described in the following sections, such thinking has led to revolutionary new concepts for managing CRPC.

Mechanisms of AR recurrence

Investigation of the means by which AR activity is restored in CRPC remains an area of fruitful discovery and is imperative for the successful design of new therapeutic interventions. To date, at least four major mechanisms have been identified in clinical specimens and validated in the laboratory as playing key roles in disease progression.

AR deregulation

As was elegantly demonstrated by Scher and colleagues, high levels of AR are independently predictive of increased risk of death from prostate cancer [44]. Combined with in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrating that overexpression of AR is sufficient to nullify the effects of ADT or maximum androgen blockade, it is not surprising that up to 30% of CRPC tumors show marked upregulation of the receptor [45–47]. Gene dosage may play a role in outcome, as it should be noted that AR gene amplification does not associate with survival in all cases [44]. Mechanistically, it is thought that AR deregulation confers sufficient basal AR activity to induce disease progression. Moreover, excessive AR production can reduce the amount of ligand required for AR-mediated tumor proliferation and survival, thus sensitizing cells to the protumorigenic effects of residual androgens [48], precursors derived from the adrenal glands or other tissues, and/or intracrine-derived androgens (discussed later). Despite this knowledge, there have been few studies to address the means by which AR upregulation occurs. A subset of tumors show amplification of the AR locus, but few studies have addressed amplification-independent or cooperative events that may bolster AR upregulation. Loss of the Pur-α corepressor or upregulation of the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1) transcription factor have been shown in model systems to induce AR gene expression [49,50], and therefore could potentially provide a means to promote CRPC. Recent studies identified an un anticipated link between AR expression and the retinoblastoma (RB) tumor suppressor, wherein it was shown that RB acts as a transcriptional repressor at the AR locus; conversely, suppression of RB results in deregulation of AR expression that is sufficient to induce CRPC in vivo. The clinical impact of these findings was validated, in that RB loss proved to be highly overrepresented in CRPC and inversely correlated with AR expression. These data indicate that in prostate cancer, a major function of the RB tumor suppressor is to dampen AR expression and signaling [51,52]. While much is yet to be learned with regard to alternate mechanisms of AR deregulation, it is clear that this process significantly contributes to, and can be causative for, CRPC formation.

Intracrine androgen synthesis

As has been recently reviewed [11,53,54], upregulation of enzymes that convert weak adrenal androgens to testosterone provides sufficient levels of agonist so as to restore AR activity under a castrate condition [55–60]. Such a paradigm was originally suggested by Geller and colleagues, who identified a link between andrenal androgens and tumor growth [61]. As is now well appreciated, adrenal-derived dehydroepiandrosterone can be converted to testosterone and DHT through the action of tumor-derived 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD/ketosteroid isomerase type 1 and type 2 [HSD3B1, HSD3B2]), type 5 17β-HSD (AKR1C3), and SRD5A2. Notably, HSD3B2, AKR1C3, SRD5A1, AKR1C2 and AKR1C1 have been shown to be altered in CRPC (as compared with primary tumors), lending support to the credence that intracrine androgen synthesis probably plays a major role in CRPC. Furthermore, upregulation of genes associated with androgen synthesis from cholesterol was observed after androgen depletion in cell-line models [62,63], and evidence of de novo DHT synthesis in CRPCs has also been reported. Given these un expected findings, it may be expected that targeting the intracrine androgen synthesis pathway would be of clinical benefit for a subset of patients. As will be discussed in the next section, this premise appears to be correct, and underlies the current use of abiraterone acetate, a CYP17,20-lyase inhibitor [64,65], in patients with CRPC.

AR mutation & alternative splicing

Somatic mutation of AR is known to be selected for during hormone therapy [66], and typically results in a gain-of-function, such that the mutated receptor can utilize an expanded repertoire of ligands as agonists [47,67]. While it was initially discovered that a subset of mutations can sensitize the receptor to activation by other steroids (including progesterone, cortisol and estrogen), use of AR antagonists can further select for mutations that convert these therapeutic agents into agonists [68]. Moreover, selected mutations resulted in stabilized receptors that demonstrated enhanced nuclear retention and function. While the incidence of AR mutation in hormone therapy-naive tumors is low, the frequency of alteration in CRPC (up to 30%) suggests that genetic alteration of the AR locus plays a significant role in tumor progression. Moreover, recent assessment of AR mutations in circulating tumor cells revealed AR mutations in 20 out of 35 patients with CRPC, indicating that the frequency of alteration could be even higher in cells with metastatic potential [69]. Development of means to therapeutically antagonize such a receptor are yet to be fully realized. Similar concerns are raised with regard to the generation of alternatively spliced AR variants, which largely result in the formation of truncated receptors. A large number of variant transcripts created by alternative splicing have been identified from cell lines and CRPC xenografts, and recent studies suggest that the cadre of variant transcripts produced is altered by castration [70–74]. A large percentage of these transcripts encode proteins that have lost most or all of the LBD and are transcriptionally active (albeit weakly); critically, such variants would therefore be expected to evade all currently accepted means to thwart AR activity in the clinic. Combined, these observations strongly suggest that alteration or loss of the LBD is utilized by the receptor to evade C-terminal-directed therapeutic intervention, and would be expected to confer bypass of castration or AR antagonist therapies. As such, it is critical to develop alternate means of suppressing AR function through C-terminal independent means.

Post-translational modifications & cofactor alteration

Distinct from alterations in AR expression, coding sequence or splicing, disparate means of post-translational modifications have been suggested to contribute to enhanced AR function in CRPC. These mechanisms include serine/threonine phosphorylation [75], tyrosine phosphorylation [76,77], acetylation [78], ubiquitylation [79,80] and sumolyation [81] of the receptor, and could conceivably act synergistically with other AR alteration events. While many of these events are known to occur downstream of growth factor pathways, it remains uncertain whether therapeutic targeting of growth factor receptors or downstream kinases shows clinical benefit. One example of putative efficacy may be targeting of the Src kinase, which induces tyrosine phosphorylation events of AR that induce receptor activity [76], and are known to be upregulated in clinical CRPC. Notably, the Src inhibitor dasatinib is currently in clinical trails for use in solid tumors including prostate cancer [82,83], and preliminary studies suggest that this approach may prove effective at suppressing AR activity [84,85]. Finally, an exhaustive body of literature suggest that AR cofactors are altered in prostate cancer, typically involving upregulation of coactivators [13], loss/dismissal of corepressors [86] or AR mutations that alter the way that cofactors are perceived [67]. These pathways have recently been reviewed [11], and with regard to a subset of factors, in vivo modeling supports the contention that cofactor alteration can contribute to aberrant AR activity. In addition to AR posttranslational modifications, these event should be considered when discerning how to apply novel AR-directed therapeutics.

Targeting AR in 2011: new understandings of AR biology lead to novel therapeutic strategies

Given the exceptionally creative means used by prostate cancer cells to evade currently utilized AR-directed therapeutics, novel mechanisms must be designed to achieve more effective, durable suppression of AR activity. The past 2 years have seen a remarkable rise in the development of experimental therapeutics intended to block resurgent AR activity in CRPC (Figure 1). The current state of the field will be reviewed herein.

Targeting intracrine androgen synthesis/increasing efficiency of androgen ablation

Based on the knowledge that recurrent AR activity is frequently driven by sensitization of the receptor to low levels of ligand in the castrate environment and/or by the onset of intracrine androgen synthesis, effective means to further reduce access of the receptor to ligand have been introduced into the clinic. This class of agents are now referred to as androgen biosynthesis inhibitors [87]. Ketoconazole was the first agent in this class and broadly interrupts the synthesis and degradation of steroids, including androgen precursors, by inhibiting cytochrome p450 enzymes [88,89]. Functionally, this agent has also been shown to be a weak androgen receptor antagonist [88]. Contemporary Phase III studies show that 28% of the patients treated with ketoconazole will respond with a 50% decrease in PSA post-therapy, with an overall median survival of 16 months [88]. Since ketoconazole is a nonspecific inhibitor of androgen synthesis, off-target toxicities such as nausea, vomiting, liver dysfunction and adrenal insufficiency complicate therapy [88]. On disease progression in patients treated with ketoconazole, an increase in adrenal androgens has been observed, which suggests that this drug does not durably suppress the critical enzymes for androgen synthesis [88]. More specific and potent inhibitors of the CYP 17 α-hydroxylase and C17,20-lyase that are essential for androgen biosynthesis have recently been introduced into the clinic. Abiraterone (CB7598) is a poorly absorbed, selective nonreversible inhibitor of the CYP 17 enyzmes that is 10–30-fold more potent than ketoconazole [90,91]. By contrast, abiraterone acetate is a 3-β-O acetate prodrug of abiraterone, which has excellent bio availability, and in Phase I studies was well tolerated with significant reduction of the PSA with improvement in tumor-related symptoms [92,93]. These early studies showed that abiraterone acetate lowered the plasma concentrations of testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone, androstenedione and estradiol to near-nondetectable concentrations, which were maintained for the duration of the study, thus indicating biochemical efficacy. Interestingly, androgen precursors did not rise on progression, as is observed with ketoconazole [90,91]. These findings indicate that the mechanism by which abiraterone acetate failure arises is distinct from that of ketoconazoles, and should be explored. A biologically active dose of 1000 mg per day was selected for further testing in combination with corticosteroids, which mitigate the toxicities of mineralocorticoid excess (hypertension and hypokalemia) [91].

A Phase II trial was initiated wherein abiraterone acetate was dosed once daily at 1000 mg for 28-day cycles until PSA progression, at which point the glucocorticoid receptor agonist dexa methasone (0.5 mg daily) was added. Within the cohort of 42 Phase II patients, 67% had a more than 50% decline in PSA, and declines of more than 90% were seen in eight patients [94]. The median time to PSA progression (TTPP) was 225 days, at which point dexamethasone 0.5 mg daily was added and yielded an additional 151 days of median TTPP. The additional response gained with dexamethasone was independent of previous treatment with dexamethasone [94]. More recently, a Phase III study randomized patients to abiraterone acetate 1000 mg daily with prednisone 5 mg twice a day versus placebo daily with prednisone 5 mg twice a day in patients with progressive CRPC. The primary end point of this study was overall survival, and 1195 patients were enrolled into the study. The preliminary results showed that patients treated with abiraterone acetate had significant improvement in overall survival compared with the placebo (14.1 vs 10.2 months; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.646; p < 0.0001) [95]. This represents a 36% improvement in the median survival of CRPC patients and a 35% risk reduction of death. The time to prostate cancer progression and the proportion of patients that had a 50% post-therapy decline in PSA also significantly favored the abiraterone arm [95]. Notably, abiraterone acetate was well tolerated, with the major adverse reactions being fluid retention, hypokalemia and liver function abnormalities and cardiac disorders that were minimal and well controlled. Overall, this trial validated the concept that androgens remain important in very advanced stages of CRPC, and showed that targeting intracrine androgen synthesis is still a viable therapeutic option. Currently there are multiple novel androgen biosynthesis inhibitors, such as TAK-700 or VN/124-1 (TOK-001) now undergoing clinical evaluation that may afford certain advantages over abiraterone acetate [96].

Novel C-terminal-directed targets

Despite the longstanding use of castration-induced ligand depletion and direct C-terminal-binding AR antagonists in the clinic, recent findings suggest that novel compounds can further improve C-terminal-directed therapeutics. The darylthiohydantoins RD162 and MDV3100 dock into the AR through the LBD and, although similar to bicalutamide in structure, both compounds harbor additional activities [97]; specifically, these agents can reduce nuclear accumulation of AR, and therefore dampen chromatin association, cofactor recruitment and AR-dependent transcriptional activation. The interim results of a Phase I/II trial of 140 patients that were either chemo-naive or post-chemotherapy with progression of CRPC were recently reported. The dose-escalation study of 30–600 mg/day administered orally was well tolerated and nearly half of the patients showed at least a 50% PSA decline at week 12; and 38% of evaluable patients receiving 240 mg/day dosing had a partial reduction of their tumor on radiographs [98]. An international Phase III placebo-controlled trial is underway using the 240 mg/day dose [201]. A concern for this class of agents has been the onset of seizures, which is thought to be off-target inhibition of γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA-A) currents [99]. Seizures have not been reported with the currently used AR antagonists, but two possible seizures were reported at the highest dose levels of the Phase I trial of MDV-31005. No seizures were reported when lower doses (240 mg or lower) of MDV-3100 were used [98]. Recently, an international Phase III placebo-controlled trial was completed using the 240 mg/day dose, and initial results show that it was well tolerated [201]. Preliminary results on the overall clinical benefit will be available in mid-2011. Finally, a small molecule that binds AR and functions to exclude the receptor from nuclear accumulation, selective nuclear receptor exporter 1 (SNARE-1), has been identified. The action of this agent appears to be remarkably tissue selective in preliminary studies, and prevents proliferation of prostate cancer cells and xenografts while showing little effect on AR in cells derived from bone. Such advances present new avenues for selectively targeting AR in tumor cells, and function through mechanisms that are distinct from currently utilized modalities [100].

A new chapter in targeting AR: promising N-terminal-directed therapeutics

One of the most exciting new developments in the field centers on reports of novel N-terminal-directed therapeutics intended to antagonize AR function. As noted, it is this domain of the receptor that harbors the main transcriptional transactivation function, and current data suggest that gain-of-function AR mutants and truncated forms of the receptor found in CRPC retain reliance on N-terminal activity. Conceptually, it has been predicted for some time that ablation of AR N-terminal-derived activity would result in marked anti-tumor activity. Thus, the small molecule EPI-001 was developed, which not only binds to the AR N-terminal transactivation domain, but also inhibits critical protein–protein interactions supported by this region, and suppresses AR association with chromatin-bound regulatory elements [101]. Objective cellular outcomes were also observed, in that EPI-001 inhibited androgen-dependent and CPRC tumor cell growth in vivo without overt host toxicity. These remarkable findings bring forth a new era in targeting AR, and are the first to definitively demonstrate feasibility for in vivo suppression of AR N-terminal domain functions. Further ana lysis of clinical efficacy is anxiously awaited.

Receptor elimination strategies: agents intended to induce receptor turnover

While ablation of AR activity remains a major biochemical goal of therapy, elimination of the receptor itself within prostate cancer cells would probably be of benefit. Such strategies are utilized in breast cancer management, in that fulvestrant not only binds to the estrogen receptor α and suppresses ligand-dependent activity, but also induces marked receptor turnover [102]. In Phase III randomized trials, fulvestrant has shown similar clinical activity to the selective aromatase inhibitor anastrozole and is approved for the use in hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer in postmenopausal women that have progressed after antiestrogen therapy [103]. With regard to AR, several compounds have been identified using in vitro and in vivo assays to reduce overall AR levels. Interestingly, an analog of abiraterone acetate, (3β-hydroxy-17-[1H-benzimidazole-1-yl]androsta-5,16-diene), not only suppresses CYP17,20-lyase activity, but is also thought to induce AR turnover [104]. If correct, this agent could conceivably act to suppress both intracrine androgen synthesis and AR accumulation. The agent was recently renamed TOK-001 and is being tested in Phase I/II trials termed the Study of TOK-001 to Treat Castration Resistant Prostate Cancer (ARMOR1) trial [96]. Several experimental agents that are in testing for other tumor sites have also demonstrated efficacy in vitro for inducing AR turnover. One such agent is curcumin, a natural compound derived from turmeric. Curcumin is known to possess significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidative activities in a number of tissues, and exerts antiproliferative effects in cancer cell lines [105,106]. In the clinical trial setting for other disease sites, curcumin was found to be safe in Phase I/II clinical studies, and there was no dose-limiting toxicity at doses up to 10 g/day [107]. Potentially pertinent to CRPC, curcumin has also been shown to markedly reduce AR levels in prostate cancer cells [108], suggesting that this agent may have promise for further investigation.

Expert commentary

The inability to effectively suppress AR activity remains a major hurdle for the development of durable means to treat advanced prostate cancer. The observations described herein exemplify the remarkable ability of the AR pathway to adapt to therapeutic intervention, and also illuminate new theoretical means to anticipate and thwart recurrent AR activity. Several of the next-generation AR antagonists or androgen ablative agents have shown promise in the clinic, and lend credence to the concept that understanding the mechanisms that lead to AR reactivation is of likely therapeutic benefit. However, several key challenges remain. First, how can we stratify patients into the most effective options for treating CRPC? So far, the means by which AR reactivation occurs in individual tumors has not been assessed or utilized at the clinical level. Patients whose tumors express truncated AR splice variants, for example, may not be responsive to agents that require the AR LBD. Developing methodology to identify such tumors and craft appropriate therapeutic strategies may be of benefit. Use of circulating tumor cells to achieve such goals remains an incompletely assessed and exciting possibility. Second, is suppression of AR post-translational modifications an under-considered and potentially effective means of therapeutic intervention? Recent studies with dasatinib suggest that suppression of c-src-mediated AR phosphorylation events may provide an alternative means of suppressing AR signaling in a subset of tumors. These studies may therefore serve as the foundation for future studies targeting AR post-translational modification events. Third, do agents that induce AR turnover act in concert with N- or C-terminal-directed therapeutics? Such combination therapies would conceptually have therapeutic benefit, yet this postulate remains to be rigorously challenged in the clinical or preclinical setting. Moreover, it should be considered whether the sequence of combination therapy affects tumor response or clinical outcomes. Fourth, what are the mechanisms that underlie tumor progression after abiratorone? The improvement in survival is modest, suggesting that delineating the means by which tumor cells escape androgen ablative therapy should be prioritized. Finally, do AR-directed therapeutics target the self-renewing population? Controversy remains as to the identity and composition of putative cancer ‘stem-like’ cells within the tumor microenvironment. There is evidence that cells with self-renewal and pluripotent activity within the tumor microenvironment express little AR, and therefore may provide an additional basis for failure of AR-directed therapeutics. Identification of means to target such a cellular population has yet to be developed. Similarly, it should be considered whether AR-negative tumors will arise at a high frequency if complete and durable AR suppression becomes a therapeutic reality. Overall, knowledge gained from interrogating the AR axis has revealed new nodes for therapeutic intervention, presenting the challenge of developing these strategies for optimal clinical gain and therein ‘outsmarting’ the elusive adaptable AR.

Five-year view

The last decade has seen a remarkable expansion in our understanding of the underlying mechanisms that promote prostate cancer progression, which have been rapidly translated into the clinic. Major advances in targeting the AR through suppression of androgen synthesis (e.g., abiraterone) and through novel agents that directly bind to and ablate AR activity (e.g., MDV3100) have yielded encouraging results in the clinic, and a tremendous number of additional agents are either in clinical trials or under development. If this pace is maintained, it is reasonable to speculate that in the next 5 years, we will see novel agents in clinical use that effectively delay, prevent or potentially reverse CRPC development. Toward this end, strides toward the development of personalized medicine are expected; in this scenario, knowledge of the mechanism(s) by which AR has been reactivated in CRPC may assist in the selection of appropriate therapeutic intervention. Finally, it is anticipated that adjuvant therapies will be identified that act in concert with AR-directed therapeutics, yielding more effective means of treating disseminated disease. Given the extraordinary advances in prostate cancer treatment within the last 5 years, there is every reason to be optimistic about the next 5 years.

Key issues.

Prostate cancer presents a major health challenge. It is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy in American men and the second leading cause of male cancer death.

Methods to durably treat disseminated prostate cancer are an urgent, unmet need. Prostate cancer is typically dependent on androgen receptor (AR) activity for development, survival and progression. As such, first-line intervention for disseminated disease is designed to ablate AR activity.

Existing AR-directed therapeutics rely on androgen deprivation (castration) strategies, sometimes used in combination with direct AR antagonists that bind to the receptor C-terminal domain. These regimens are typically effective, and result in suppression of AR activity (verified through suppression of prostate-specific antigen expression, which is under direct AR control) and concomitant tumor regression.

Ultimately, recurrent, castrate-resistant tumors (castratation-resistant prostate cancers [CRPCs]) emerge, for which no durable means of treatment has been identified. A plethora of clinical and preclinical studies revealed that the major means of CRPC formation occurs through inappropriate reactivation of AR.

Delineation of the mechanisms that promote AR reactivation and resultant CRPC illuminate the extraordinary ability of cells to adapt to first-line therapies and restore AR function, as achieved through alterations that can occur either upstream of, or proximal to, the receptor itself.

Knowledge gained about the mechanisms of AR reactivation has provided essential insights into means of targeting the adaptive process. New therapeutic regimens that block intracrine androgen synthesis (which can be induced in response to castration), or bind directly to AR and suppress receptor activity through novel means show remarkable promise in the clinical treatment of CRPC.

Additional agents that target receptor stability, suppress receptor accumulation or target motifs critical for AR function in CRPC are in advanced stages of development or clinical trials.

Hurdles remain regarding to how to stratify patients into the most effective treatment options. In addition, it remains uncertain whether complete ablation of AR activity will result in cure, or the development of recurrent tumors reliant on bypass pathways.

Acknowledgements

The authors regret any omission of citations due to space constraints. They would also like to thank Michael Augello, Jonathan Goodwin, Matthew Schiewer and Randy Schrecengost for critical feedback and ongoing disussions, and Elizabeth Schade for assistance with illustrations.

Karen E Knudsen is supported by grants CA09996 and ES16675 from the NIH.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh J, Trabulsi EJ, Gomella LG. Is there an optimal management for localized prostate cancer? Clin. Interv. Aging. 2010;5:187–197. doi: 10.2147/cia.s6555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grubb RL, Kibel AS. High-risk localized prostate cancer: role of radical prostatectomy. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2010;20:204–210. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3283384101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garzotto M, Hung AY. Contemporary management of high-risk localized prostate cancer. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2010;11:159–164. doi: 10.1007/s11934-010-0101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stratton KL, Chang SS. Locally advanced prostate cancer, the role of surgical management. BJU Int. 2009;104:449–454. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen KE, Scher HI. Starving the addiction: new opportunities for durable suppression of AR signaling in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:4792–4798. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scher HI, Sawyers CL. Biology of progressive, castration-resistant prostate cancer: directed therapies targeting the androgen-receptor signaling axis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:8253–8261. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.4777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Sawyers CL, Scher HI. Targeting the androgen receptor pathway in prostate cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2008;8:440–448. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohler JL. A role for the androgen-receptor in clinically localized and advanced prostate cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;22:357–372. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knudsen KE, Penning TM. Partners in crime: deregulation of AR activity and androgen synthesis in prostate cancer. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;21:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agus DB, Cordon-Cardo C, Fox W, et al. Prostate cancer cell cycle regulators: response to androgen withdrawal and development of androgen independence. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1869–1876. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.21.1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agoulnik IU, Weigel NL. Androgen receptor coactivators and prostate cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;617:245–255. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Culig Z, Bartsch G. Androgen axis in prostate cancer. J. Cell Biochem. 2006;99:373–381. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Claessens F, Denayer S, Van Tilborgh N, Kerkhofs S, Helsen C, Haelens A. Diverse roles of androgen receptor (AR) domains in AR-mediated signaling. Nucl. Recept. Signal. 2008;6:e008. doi: 10.1621/nrs.06008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centenera MM, Harris JM, Tilley WD, Butler LM. The contribution of different androgen receptor domains to receptor dimerization and signaling. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008;22:2373–2382. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dehm SM, Tindall DJ. Androgen receptor structural and functional elements: role and regulation in prostate cancer. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;21:2855–2863. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Askew EB, Gampe RT, Jr, Stanley TB, Faggart JL, Wilson EM. Modulation of androgen receptor activation function 2 by testosterone and dihydrotestosterone. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:25801–25816. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703268200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Q, Li W, Zhang Y, et al. Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell. 2009;138:245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.056. • Using unbiased analyses this study demonstrated that androgen receptor (AR) function is variant in castration-resistant tumor cells, thus demonstrating that recurrent AR activity induces altered gene-expression patterns.

- 20.Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, et al. A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:380–392. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cleutjens KB, van Eekelen CC, van der Korput HA, Brinkmann AO, Trapman J. Two androgen response regions cooperate in steroid hormone regulated activity of the prostate-specific antigen promoter. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:6379–6388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene KL, Albertsen PC, Babaian RJ, et al. Prostate specific antigen best practice statement: 2009 update. J. Urol. 2009;182:2232–2241. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lilja H, Ulmert D, Vickers AJ. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer: prediction, detection and monitoring. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:268–278. doi: 10.1038/nrc2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jia L, Berman BP, Jariwala U, et al. Genomic androgen receptor-occupied regions with different functions, defined by histone acetylation, coregulators and transcriptional capacity. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupien M, Brown M. Cistromics of hormone-dependent cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2009;16:381–389. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tomlins SA, Rhodes DR, Perner S, et al. Recurrent fusion of TMPRSS2 and ETS transcription factor genes in prostate cancer. Science. 2005;310:644–648. doi: 10.1126/science.1117679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C, Yang L, Tanasa B, et al. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell. 2009;139:1069–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mani RS, Tomlins SA, Callahan K, et al. Induced chromosomal proximity and gene fusions in prostate cancer. Science. 2009;326:1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1178124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cai C, Wang H, Xu Y, Chen S, Balk SP. Reactivation of androgen receptor-regulated TMPRSS2:ERG gene expression in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:6027–6032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clark JP, Cooper CS. ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2009;6:429–439. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zong Y, Xin L, Goldstein AS, Lawson DA, Teitell MA, Witte ON. ETS family transcription factors collaborate with alternative signaling pathways to induce carcinoma from adult murine prostate cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12465–12470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905931106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter J. Observations on certain parts of the animal oeconomy. In: Palmer JF, editor. The Complete Works of John Hunter. Vol. 68. Haswell, Barrington & Haswell; PA, USA: 1841. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huggins C. Effect of orchiectomy and irradiation on cancer of the prostate. Ann. Surg. 1942;115:1192–1200. doi: 10.1097/00000658-194206000-00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huggins C. The treatment of cancer of the prostate: (The 1943 address in surgery before the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada) Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1944;50:301–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huggins C, Hodges CV. Studies on prostatic cancer. I. The effect of castration, of estrogen and androgen injection on serum phosphatases in metastatic carcinoma of the prostate. CA Cancer J. Clin. 1972;22:232–240. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.22.4.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klotz L. Maximal androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;22:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beekman KW, Hussain M. Hormonal approaches in prostate cancer: application in the contemporary prostate cancer patient. Urol. Oncol. 2008;26:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shang Y, Myers M, Brown M. Formation of the androgen receptor transcription complex. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:601–610. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Dosso S, Berthold DR. Docetaxel in the management of prostate cancer: current standard of care and future directions. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2008;9:1969–1979. doi: 10.1517/14656566.9.11.1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sonpavde G, Sternberg CN. The role of docetaxel based therapy for prostate cancer in the era of targeted medicine. Int. J. Urol. 2010;17:228–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2010.02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kantoff PW, Higano CS, Shore ND, et al. Sipuleucel-T immunotherapy for castration-resistant prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;363:411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen CD, Welsbie DS, Tran C, et al. Molecular determinants of resistance to antiandrogen therapy. Nat. Med. 2004;10:33–39. doi: 10.1038/nm972. •• This landmark study was among the first to demonstrate that recurrent AR activity is a major mechanism of resistance to hormone therapy, and that upregulation of AR alone is sufficient to drive this process.

- 44.Donovan MJ, Osman I, Khan FM, et al. Androgen receptor expression is associated with prostate cancer-specific survival in castrate patients with metastatic disease. BJU Int. 2010;105:462–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohler JL. Castration-recurrent prostate cancer is not androgen-independent. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2008;617:223–234. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-69080-3_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ford OH, 3rd, Gregory CW, Kim D, Smitherman AB, Mohler JL. Androgen receptor gene amplification and protein expression in recurrent prostate cancer. J. Urol. 2003;170:1817–1821. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000091873.09677.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linja MJ, Visakorpi T. Alterations of androgen receptor in prostate cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;92:255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Waltering KK, Helenius MA, Sahu B, et al. Increased expression of androgen receptor sensitizes prostate cancer cells to low levels of androgens. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8141–8149. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang LG, Johnson EM, Kinoshita Y, et al. Androgen receptor overexpression in prostate cancer linked to Pur α loss from a novel repressor complex. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2678–2688. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y, Wang L, Zhang M, et al. LEF1 in androgen-independent prostate cancer: regulation of androgen receptor expression, prostate cancer growth, and invasion. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3332–3338. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sharma A, Yeow WS, Ertel A, et al. The retinoblastoma tumor suppressor controls androgen signaling and human prostate cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4478–4492. doi: 10.1172/JCI44239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Macleod KF. The RB tumor suppressor: a gatekeeper to hormone independence in prostate cancer? J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:4179–4182. doi: 10.1172/JCI45406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mostaghel EA, Montgomery B, Nelson PS. Castration-resistant prostate cancer: targeting androgen metabolic pathways in recurrent disease. Urol. Oncol. 2009;27:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yuan X, Balk SP. Mechanisms mediating androgen receptor reactivation after castration. Urol. Oncol. 2009;27:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bauman DR, Steckelbroeck S, Williams MV, Peehl DM, Penning TM. Identification of the major oxidative 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in human prostate that converts 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol to 5α-dihydrotestosterone: a potential therapeutic target for androgen-dependent disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 2006;20:444–458. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Penning TM, Steckelbroeck S, Bauman DR, et al. Aldo-keto reductase (AKR) 1C3: role in prostate disease and the development of specific inhibitors. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2006;248:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Locke JA, Guns ES, Lubik AA, et al. Androgen levels increase by intratumoral de novo steroidogenesis during progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6407–6415. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4447–4454. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. •• Provides robust evidence for the importance of intratumoral androgens in castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

- 59.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, et al. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:2815–2825. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. • Among the first studies to demonstrate that intracrine androgen synthesis may play a significant role in tumor progression.

- 60.Mostaghel EA, Page ST, Lin DW, et al. Intraprostatic androgens and androgen-regulated gene expression persist after testosterone suppression: therapeutic implications for castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5033–5041. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geller J, Albert J, Vik A. Advantages of total androgen blockade in the treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Semin. Oncol. 1988;15:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dillard PR, Lin MF, Khan SA. Androgen-independent prostate cancer cells acquire the complete steroidogenic potential of synthesizing testosterone from cholesterol. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2008;295:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suzuki K, Nishiyama T, Hara N, Yamana K, Takahashi K, Labrie F. Importance of the intracrine metabolism of adrenal androgens in androgen-dependent prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10:301–306. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fong L, et al. Phase I clinical trial of the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetate demonstrating clinical activity in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer who received prior ketoconazole therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1481–1488. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reid AH, Attard G, Danila DC, et al. Significant and sustained antitumor activity in post-docetaxel, castration-resistant prostate cancer with the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetate. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1489–1495. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Steinkamp MP, O’Mahony OA, Brogley M, et al. Treatment-dependent androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancer exploit multiple mechanisms to evade therapy. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4434–4442. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brooke GN, Bevan CL. The role of androgen receptor mutations in prostate cancer progression. Curr. Genomics. 2009;10:18–25. doi: 10.2174/138920209787581307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Terada N, Shimizu Y, Yoshida T, et al. Antiandrogen withdrawal syndrome and alternative antiandrogen therapy associated with the W741C mutant androgen receptor in a novel prostate cancer xenograft. Prostate. 2010;70:252–261. doi: 10.1002/pros.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang Y, Palma JF, Agus DB, Wang Y, Gross ME. Detection of androgen receptor mutations in circulating tumor cells in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Chem. 2010;56:1492–1495. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.143297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Watson PA, Chen YF, Balbas MD, et al. Constitutively active androgen receptor splice variants expressed in castration-resistant prostate cancer require full-length androgen receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:16759–16765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012443107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sun S, Sprenger CC, Vessella RL, et al. Castration resistance in human prostate cancer is conferred by a frequently occurring androgen receptor splice variant. J. Clin. Invest. 2010;120:2715–2730. doi: 10.1172/JCI41824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo Z, Yang X, Sun F, et al. A novel androgen receptor splice variant is up-regulated during prostate cancer progression and promotes androgen depletion-resistant growth. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2305–2313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dehm SM, Schmidt LJ, Heemers HV, Vessella RL, Tindall DJ. Splicing of a novel androgen receptor exon generates a constitutively active androgen receptor that mediates prostate cancer therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5469–5477. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0594. • This study was the first to identify AR splice variants as potential mediators of CRPC phenotypes, and set the stage for uncovering clinical relevance of protein products arising from the alternative splicing events.

- 74.Hu R, Dunn TA, Wei S, et al. Ligand-independent androgen receptor variants derived from splicing of cryptic exons signify hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:16–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ward RD, Weigel NL. Steroid receptor phosphorylation: assigning function to site-specific phosphorylation. Biofactors. 2009;35:528–536. doi: 10.1002/biof.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guo Z, Dai B, Jiang T, et al. Regulation of androgen receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mahajan NP, Liu Y, Majumder S, et al. Activated Cdc42-associated kinase Ack1 promotes prostate cancer progression via androgen receptor tyrosine phosphorylation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8438–8443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700420104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Popov VM, Wang C, Shirley LA, et al. The functional significance of nuclear receptor acetylation. Steroids. 2007;72:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dirac AM, Bernards R. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP26 is a regulator of androgen receptor signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 2010;8:844–854. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-09-0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xu K, Shimelis H, Linn DE, et al. Regulation of androgen receptor transcriptional activity and specificity by RNF6-induced ubiquitination. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:270–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaikkonen S, Jaaskelainen T, Karvonen U, et al. SUMO-specific protease 1 (SENP1) reverses the hormone-augmented SUMOylation of androgen receptor and modulates gene responses in prostate cancer cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 2009;23:292–307. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Araujo J, Logothetis C. Dasatinib: a potent SRC inhibitor in clinical development for the treatment of solid tumors. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010;36:492–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saad F, Lipton A. SRC kinase inhibition: targeting bone metastases and tumor growth in prostate and breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2010;36:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Liu Y, Karaca M, Zhang Z, Gioeli D, Earp HS, Whang YE. Dasatinib inhibits site-specific tyrosine phosphorylation of androgen receptor by Ack1 and Src kinases. Oncogene. 2010;29:3208–3216. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cai H, Babic I, Wei X, Huang J, Witte ON. Invasive prostate carcinoma driven by c-src and androgen receptor synergy. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):862–872. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Burd CJ, Morey LM, Knudsen KE. Androgen receptor corepressors and prostate cancer. Endocr. Relat. Cancer. 2006;13:979–994. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.01115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Attard G, Reid AH, de Bono JS. Abiraterone acetate is well tolerated without concomitant use of corticosteroids. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:e560–e561. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5170. author reply e562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ryan CJ, Halabi S, Ou SS, Vogelzang NJ, Kantoff P, Small EJ. Adrenal androgen levels as predictors of outcome in prostate cancer patients treated with ketoconazole plus antiandrogen withdrawal: results from a Cancer and Leukemia Group B study. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007;13:2030–2037. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taplin ME, Regan MM, Ko YJ, et al. Phase II study of androgen synthesis inhibition with ketoconazole, hydrocortisone, and dutasteride in asymptomatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:7099–7105. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ryan CJ, Smith MR, Fong L, et al. Phase I clinical trial of the CYP17 inhibitor abiraterone acetate demonstrating clinical activity in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer who received prior ketoconazole therapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;28:1481–1488. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Attard G, Reid AH, Yap TA, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:4563–4571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749. •• Utilization of CYP17 inhibitors shows clinical promise, further underscoring the importance of intracrine androgen synthesis for CRPC.

- 92.Attard G, Reid AHM, Yap TA, et al. Phase I clinical trial of a selective inhibitor of CYP17, abiraterone acetate, confirms that castration-resistant prostate cancer commonly remains hormone driven. J. Clin. Oncol. 2010;2008:4563–4571. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.De Bono JS, Attard G, Reid AH, et al. Anti-tumor activity of abiraterone acetate (AA), a CYP17 inhibitor of androgen synthesis, in chemotherapy naive and docetaxel pre-treated castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26 (Abstract 5005) [Google Scholar]

- 94.Attard G, Reid AHM, A’Hern R, et al. Selective inhibition of CYP17 with abiraterone acetate is highly active in the treatment of castration-resistant prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:3742–3748. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Fizazi K, et al. Abiraterone acetate plus low dose prednisone improves overall survival in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have progressed after docetaxel-based chemotherapy: results of COU-AA-301, a randomized double blinded placebo controlled Phase III study. Ann. Oncol. 2010;21:viii3. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vasaitis TS, Bruno RD, Njar VCO. CYP17 inhibitors for prostate cancer therapy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.11.005. DOI: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.11.005. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tran C, Ouk S, Clegg NJ, et al. Development of a second-generation antiandrogen for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. Science. 2009;324:787–790. doi: 10.1126/science.1168175. •• Describes the development of MDV3100, a second-generation AR antagonist with expanded capabilities for suppressing AR activity.

- 98.Scher HI, Beer TM, Higano CS, et al. Antitumor activity of MDV3100 in a Phase I/II study of castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27 (Abstract 5011) • Early results with MDV3100 show clinical anti-tumor activity of the second-generation AR antagonist.

- 99.Foster WR, Car BD, Shi H, et al. Drug safety is a barrier to the discovery and development of new androgen receptor antagonists. Prostate. 2010;71(5):480–488. doi: 10.1002/pros.21263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Narayanan R, Yepuru M, Szafran AT, et al. Discovery and mechanistic characterization of a novel selective nuclear androgen receptor exporter for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:842–851. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Andersen RJ, Mawji NR, Wang J, et al. Regression of castrate-recurrent prostate cancer by a small-molecule inhibitor of the amino-terminus domain of the androgen receptor. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.04.027. •• Describes the development of a new compound that is directed against the AR N-terminus, thus breaking critical new ground for means to thwart recurrent AR activity.

- 102.Baumann CK, Castiglione-Gertsch M. Clinical use of selective estrogen receptor modulators and down regulators with the main focus on breast cancer. Minerva Ginecol. 2009;61:517–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Buzdar A, Jonat W, Howell A, et al. Anastrozole, a potent and selective aromatase inhibitor, versus megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer: results of overview analysis of two Phase III trials. Arimidex Study Group. J. Clin. Oncol. 1996;14:2000–2011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vasaitis T, Belosay A, Schayowitz A, et al. Androgen receptor inactivation contributes to antitumor efficacy of 17α hydroxylase/17,20-lyase inhibitor 3β-hydroxy-17-(1H-benzimidazole-1-yl) androsta-5,16-diene in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2348–2357. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Teiten MH, Gaascht F, Eifes S, Dicato M, Diederich M. Chemopreventive potential of curcumin in prostate cancer. Genes Nutr. 2010;5:61–74. doi: 10.1007/s12263-009-0152-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dorai T, Gehani N, Katz A. Therapeutic potential of curcumin in human prostate cancer-I. Curcumin induces apoptosis in both androgen-dependent and androgen-independent prostate cancer cells. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2000;3:84–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.pcan.4500399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sharma RA, Euden SA, Platton SL, et al. Phase I clinical trial of oral curcumin: biomarkers of systemic activity and compliance. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:6847–6854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nakamura K, Yasunaga Y, Segawa T, et al. Curcumin down-regulates AR gene expression and activation in prostate cancer cell lines. Int. J. Oncol. 2002;21:825–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Website

- 201.Clinicaltrials.gov. 2009 Search results for abiraterone http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=abiraterone.