Abstract

Evolutionarily, what was the earliest engram? Biology has evolved to encode representations of past events, and in neuroscience, we are attempting to link experience-dependent changes in molecular signaling with cellular processes that ultimately lead to behavioral output. The theory of evolution has guided biological research for decades, and since phylogenetically conserved mechanisms drive circadian rhythms, these processes may serve as common predecessors underlying more complex behavioral phenotypes. For example, the cAMP/MAPK/CREB cascade is interwoven with the clock to trigger circadian output, and is also known to affect memory formation. Time-of-day dependent changes have been observed in long-term potentiation (LTP) within the suprachiasmatic nucleus and hippocampus, along with light-induced circadian phase resetting and fear conditioning behaviors. Together this suggests during evolution, similar processes underlying metaplasticity in more simple circuits may have been redeployed in higher-order brain regions. Therefore, this notion predicts a model that LTP and metaplasticity may exist in neural circuits of other species, through phylogenetically conserved pathways, leading to several testable hypotheses.

Keywords: transcription, translation, metabolism, sleep, excitability

Evolutionary Emergence of “Memory”: A Perspective

Early forms of life likely encoded molecular processes which integrated basic information necessary for survival: simple environmental stimuli and nutrition, such as light or temperature and essential chemicals (nutrients) for biological energy utilization and early metabolic chemical reactions. The cyclical nature of the earth’s rotation on its axis, and orbit around the sun, would have provided daily (circadian) and seasonal (circannual) oscillatory cues from which biology would have evolved molecular mechanisms that optimized energy expenditure from energy acquisition and storage (bioenergetics). Therefore these cyclical events could be considered one basis from which primordial molecular memory evolved.

The repetitive nature of cycling environmental stimulus factors, such as light and temperature, and their overlap with the availability of essential nutrients would have led to early life exhibiting a “timed” and coordinated molecular signature, and in turn this could have led to an organization of molecular and cellular processes contributing to a behavioral response which coincided with regular, cyclical, and predictable stimuli (Figure 1). These stimulating events, while repetitive, would have retained some variance over time, such as annual periodic changes in day length. Modulation of stimuli would therefore have led this “timing” machinery subject to an adaptive quality, making the system plastic, and able to adjust to the changing environment, setting optimization limits for energy use and storage. Additional variations in the relative amount of periodicity, due to changes in periods of other regularly occurring environmental cycles, such as circalunar and circatidal rhythms (Tessmar-Raible et al., 2011), contributed further plasticity within this rhythmic biological mechanism, producing an additive ability to be plastic, referred to here broadly as metaplasticity (Bienenstock et al., 1982; Abraham and Bear, 1996; Jedlicka, 2002), a term adopted from neuroscience describing the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. For this discussion, “metaplasticity” refers to any biological system to change its ability to be plastic. Further modifications to periodicity can be influenced by Earth’s orbit eccentricity, axial tilt, and precession. These changes are believed to contribute too much larger periodic environmental oscillations called Milankovitch cycles, leading to a global climatic “pacemaker of the ice ages” (Hays et al., 1976). Individual components can vary in period length, and oscillate over large spans of time, from tens to over hundreds of thousands of years. These variations would induce changes in seasonal alterations in daily periodicity broadly over evolutionary time, reinforcing a metaplastic quality in the biological system (Figure 1). However, within early life, the repetitive nature of specific features on shorter time-courses would have allowed more “predictable” alterations in biochemical reactions, leading to a rudimentary process of memory. Thus, an outcome of natural selection on these entrained clocks would have been the ability to “free-run” in the absence of external cues (Pittendrigh, 1993), exhibiting the earliest form of “memory” in biology.

FIGURE 1.

Evolutionary progress of the clock and metaplasticity. Upper: In early life, recurring environmental stimuli would set up a biological timing mechanism that involves an autoregulatory feedback loop, which would be integrated with metabolic processes. These in turn would lead to behavioral output processes that optimize chances for survival, through gating the organism to appropriate environmental niches. Lower: This process would become much more refined over evolutionary time, such that environmental oscillators which occur on regular frequencies would render the timing mechanism some resistance to change, such that in the absence of the regularly occurring cue (for example, a daily light–dark cycle), the mechanism would continue to persist. This would be evolutionarily advantageous, and permit the organism to place itself in its appropriate niche through memory. This mechanism would necessarily require an adaptive component, since there would be alterations in the environment that would “reset” optimization limits, rendering the system to have a “metaplastic” quality. The metaplasticity of the system instills a scaled learning component balanced against resistance (memory) mechanisms, creating an integrated processor that improves fitness during natural selection.

Optimization set-points in environmental conditions would have provided extremes for life to exist and thrive, similar to limits on a spectrum. For life to survive optimally, an adaptive quality with this changing spectrum is absolutely essential, and rationale for why circadian clocks are thought to have evolved out of periodic changes in the environment (Paranjpe and Sharma, 2005; McIntosh et al., 2010). This manuscript is not meant to set a base for this argument, but instead propose that the metaplasticity that is observed in neuronal networks and complex behavior in higher-order organisms today could have evolved out of more simple adaptive molecular machinery, such as from clock-forming cellular processes and circuits from long ago. Therefore, this adaptive quality needs to be a part of a general programming scheme within the organism, but could be viewed as fundamental to persistent behavioral qualities that better suited species survival during natural selection.

The notion that biochemical and molecular mechanisms which drive circadian rhythms known to exist in life today represent an ancient memory-coding strategy that evolved from earlier life seems quite plausible. Basic cellular processes, such as transcription and translation, are necessary for a functional clock broadly throughout life. It is well known that circadian core clock molecules, such as CLOCK and BMAL are transcription factors themselves, and operate on a transcriptional, translational autoregulatory feedback loop (Figure 2). These proteins are a part of the Per-Arnt-Sim (PAS) domain family that regulate anticipatory and adaptive responses to changes in the environment (McIntosh et al., 2010). PAS molecules in this loop are critical for the oscillatory nature of the circadian clock, and have also been shown to be involved in various temporal-sensitive processes, such as cell cycle regulation, metabolism, and learning and memory. While there is some overlap in circadian gene homology and function across certain phyla (Panda et al., 2002), strict phylogenetic conservation of specific clock genes is not as completely conserved, but instead resembles a similar operational pathway, consisting of an autoregulatory activation and repression loop structure (Friesen and Block, 1984; Brenner et al., 1990; Bass and Takahashi, 2011). The phylogenetically conserved mechanism then is an activation and repression feedback system (Figure 1), which can persist in an oscillatory nature in the absence of environmental cues to maintain cycling, but retains adaptive qualities to react to changes in the environment.

FIGURE 2.

Molecular components of the core clock. Light stimulates glutamatergic synaptic activation via the retinohypothalamic tract on NMDA receptors within the mammalian SCN, to generate signaling cascades which are mediated by various plasticity-related proteins. The cascade can reset the transcriptional/translational autoregulatory feedback loop to varying degrees based on the time-of-day. This shifting balance in the capacity of the system to regulate changes in behavioral output differentially is central to the notion of circadian metaplasticity in physiology and behavior. Refer to text for further information regarding the signaling pathways and abbreviations.

Recently, it has been shown that persistent cycling processes of peroxiredoxin enzymatic activity occurs independently of transcription in both humans and green algae (O’Neill and Reddy, 2011; O’Neill et al., 2011). The KaiC protein of cyanobacteria can also be phosphorylated in a cyclical manner, and persist in the absence of a zeitgeber (“time-giver”) independently of transcriptional and translational mechanisms (Nakajima et al., 2005; Tomita et al., 2005). However, it should be noted that in intact cyanobacteria, KaiC cyclic phosphorylation is coupled with transcriptional rhythms (Kitayama et al., 2008). Therefore it is likely that basic timing systems, such as those coupling nucleotide signaling and energy utilization in a simple negative feedback structure, may have predated more complex cellular processes, in order to optimize internal bioenergetic signaling with varying environmental conditions, thus generating rhythmic outputs which remain adaptive and able to enhance fitness and survival (Figure 1). Evolutionarily more recent oscillators involving transcriptional–translational feedback loops may have emerged after, but remain coupled to, more ancient metabolic oscillators. This coupling would have contributed to enhancement of fuel-utilization cycling, and predicts yet to be identified signaling cofactors which link circadian and metabolic processes together (Bass and Takahashi, 2011). Taken together, this suggests that some least common ancient time-keeping mechanism linking energetic and adaptive qualities would have evolved to increase fitness and survival, and derive the historical predecessor of molecular and cellular memory properties reused in higher-order organisms with central nervous systems.

Periodic cycles of environmental stimuli would have contributed to selection pressures for these least common timekeeping mechanisms, and allowed for an adaptive advantage, since survival could be enhanced with properly timed anticipatory behavior that better matched nutrient availability and reproductive fitness. Therefore, these clocks likely emerged during evolution out of natural selection; a primitive process predating higher-order memory processes tied to later evolved neuronal systems. These ancient molecular and cellular “timing” mechanisms serve as a basis for supporting more complex learning and memory-coding strategies that we are now trying to understand today. By understanding the functional relationships between these circadian time-keeping mechanisms in simple organisms, we may be able to better approach the questions to test in higher-order species with more complex nervous systems and behaviors.

Circadian Plasticity: from Molecules to Circuits to Behavior

The biological clock resides within the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus in mammals, and the underlying molecular biology and neurophysiology can “free-run” in the absence of environmental cues, or be reset to environmental stimuli, depending on the time-of-day or type of input, leading to differential changes in behavioral output (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). The basic core clock consists of a transcriptional feedback network where CLOCK and BMAL heterodimerize to transactivate Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry) gene expression through E-box elements in the promoter (Figure 2). Per and Cry heterodimerize in the cytoplasm upon phosphorylation by proteins such as casein kinase I (CKI) that regulate protein turnover to inhibit CLOCK:BMAL (Mohawk and Takahashi, 2011). While the majority of neurons in the SCN are GABAergic (Moore and Speh, 1993), photic stimulation of glutamatergic N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDA-R) - mediates calcium (Ca2+) influx, leading to downstream signaling cascades. Voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCC) are rhythmically expressed (Nahm et al., 2005), and have been implicated in light- and glutamate-induced phase shifts (Kim et al., 2005), and tie Ca2+ influx to downstream clock machinery (Ikeda et al., 2003; Ikeda, 2004). Inositol trisphosphate receptor (IP3R) expression also cycles, with Type I peaking during the early dark phase, and Type III peaking near the late dark period (Hamada et al., 1999b), and can regulate the level of Ca2+ in the SCN (Hamada et al., 1999a). NMDA-R mediated Ca2+ influx also triggers nitric-oxide synthase (NOS) to liberate nitric oxide (NO) causing a phase delay when light is delivered in the early dark phase, or a phase advance when given later in the dark period (Ding et al., 1994). NO-dependent activation of a neuronal ryanodine receptor (RyR) and protein kinase G (PKG) pathways have been implicated in phase shifts (Weber et al., 1995; Mathur et al., 1996; Ding et al., 1998; Oster et al., 2003; but see Langmesser et al., 2009). NOS activation by CaMKII phosphorylation (P) is necessary for normal light-induced phase shifts in the SCN (Agostino et al., 2004), and gates the activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase (GC) and thought to lead to cGMP–PKG signaling (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). The time-of-day sensitivity of this mechanism to respond to light-induced phase shifts also appears to be regulated through phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity, via cGMP degradation (Ferreyra and Golombek, 2001). These events are in anti-phase to what is observed for cAMP-regulated phase shifts that occur during the light phase (Prosser and Gillette, 1989; Prosser et al., 1989). Activation of the cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway in the SCN is also known to promote the effects of light/glutamate on Period1 gene expression early in the dark period, but not late in the dark period (Tischkau et al., 2000), suggesting variable pathways could converge on CREB activation to promote changes in SCN clock gene expression (Figure 2).

Stimulation of the SCN by light, exogenous glutamate, or NO was able to generate a phase-response curve that correlated with the amount of time-of-day dependent induction of CREB phosphorylation (Ding et al., 1994, 1997; von Gall et al., 1998). Both CREB phosphorylation and downstream transcription follow a circadian rhythm in the SCN (Obrietan et al., 1999), an effect that is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; Obrietan et al., 1998), which has been shown to influence BMAL activity (Sanada et al., 2002; Akashi et al., 2008). Similar processes are in common with the time-of-day expression and persistence of hippocampal-dependent memory (Eckel-Mahan et al.,2008), which depends on an intact SCN (Phan et al., 2011), suggesting conservation in cAMP/MAPK/CREB-dependent mechanisms that underlie plasticity and behavior. The ability to phase-shift circadian rhythms is also dependent on de novo protein synthesis (Jacklet, 1977; Comolli et al., 1994; Zhang et al., 1996), indicating that similar to those in long-term memory, activity-dependent plasticity-related processes also mediate circadian behavioral responses (Amir et al., 2002). Previously it has been shown that the number of photons of light correlated with the amount of the immediate-early gene c-fos mRNA expression in the SCN, which in turn correlated with the amount of phase-shift behavioral response, at times when the circadian clock is susceptible to phase-shifts (Kornhauser et al., 1990), and these effects are tightly coupled with CREB phosphorylation (Ginty et al., 1993). These data suggest that activation of the SCN stimulates plasticity-related processes during a specific temporal window, but CREB-related mechanisms exist which render the neurons permissive to changes in stimulation based on the time-of-day.

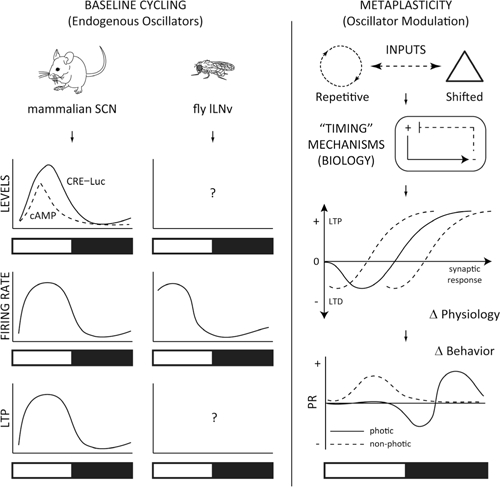

Exactly how the transcriptional/translational molecular clock operates on neurophysiological changes is not well understood (Ko et al., 2009; Colwell, 2011), but is believed to involve intercellular coupling of these cellular processes with synchronization of neuronal networks (Mohawk and Takahashi, 2011). Circadian modulation of action potential firing rates (Green and Gillette, 1982; Cutler et al., 2003; Atkinson et al., 2011) and amplitude (Belle et al., 2009) are known to exist, and include changes in the activity of ion channels, such as the fast-delayed rectifier (Itri et al., 2005), BK-channel induced calcium-activated potassium current (Kent and Meredith, 2008), and the A-type potassium currents (Itri et al., 2010). Changes in SCN neurophysiology has been shown to regulate gene expression, since blockage of firing using TTX has been shown to reduce the amplitude of Period transcript levels (Yamaguchi et al., 2003). Additionally, the neuropeptide vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) has been shown to regulate molecular oscillations (Maywood et al., 2006) and firing rates (Aton et al., 2005) in the SCN. Intracellular production of cAMP via adenylate cyclase is stimulated by VIP acting on the VPAC2 receptor (Harmar et al., 2002). Time-of-day changes in the levels of intracellular cAMP are thought to contribute to persistent oscillations of the transcriptional clock (O’Neill et al., 2008). Since the activity of hyperpolarization-activated, cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels is also necessary for circadian gene expression to be maintained in slice preparations of the SCN (O’Neill et al., 2008), it was thought that cAMP could regulate firing rates of SCN neurons through activation of HCN channels (Atkinson et al., 2011). However, cAMP was not a potent regulator of HCN channel function in SCN slice preparations, suggesting that the way in which cAMP signaling maintains the molecular clock and AP firing in the SCN still needs to be determined (Atkinson et al., 2011). It is interesting to note, however, that the peaks in time-of-day variations in cAMP and CRE–Luc activity (O’Neill et al., 2008) occur at the same time as peaks in both firing rate and resting membrane potential (Green and Gillette, 1982; Groos and Hendriks, 1982; de Jeu et al., 1998; Pennartz et al., 2002; Kuhlman and McMahon, 2004; Kononenko et al., 2008) and long-term potentiation (LTP; Nishikawa et al., 1995) in the SCN (Figure 3), suggesting functional links related to changes in expression of these molecules and as of yet to be identified channels may underlie the observed changes in neurophysiology.

FIGURE 3.

Models for testing circadian metaplasticity. Left: The mammalian SCN has an endogenous circadian rhythm of cAMP and cAMP responsive element (CRE)–luciferase (Luc)-mediated transcription (O’Neill et al., 2008), that are elevated temporally with time-of-day increases in firing rate (Green and Gillette, 1982; Welsh et al., 1995; Quintero et al., 2003; Meredith et al., 2006) and long-term potentiation (LTP; Nishikawa et al., 1995). Drosophila clock cells, the large Lateral Ventral neurons (lLNv) have a similar circadian profile of firing rate (Cao and Nitabach, 2008; Sheeba et al., 2008; Fogle et al., 2011). While Drosophila exhibit robust circadian-driven CRE–Luc activity broadly (Belvin et al., 1999), it is unclear whether cAMP or CRE–Luc activity correlates with this activity in the lLNvs, or if these cells exhibit LTP, based on the time-of-day. Right: Changes in cycling environmental inputs signal to the organism’s timing mechanisms, and integrates the incoming signal with the endogenous oscillators, engaging adaptive and resistant molecular and cellular processes. These biological processes confer a neurophysiological correlate in the neural network in the metaplastic synaptic response, which in turn generates a “metaplastic” change in behavior, based on the time-of-day. A typical phase-response (PR) curve is shown for photic and non-photic stimulation (Golombek and Rosenstein, 2010). This scheme can be generalized to more complex cognitive processes, such as hippocampal molecular signaling, synaptic plasticity and memory, which also display time-of-day dependent changes in cAMP/MAPK/CREB activity, LTP and fear conditioning (Gerstner and Yin, 2010).

High-frequency stimulation of the optic tract induces LTP in the rat SCN that varies in field excitatory postsynaptic potentials based on the time-of-day (Nishikawa et al., 1995). This effect can be considered a bona-fide occurrence of metaplasticity (Abraham, 2008) since the same stimulation regimen can generate differences in fEPSP. Time-of-day metaplasticity is also observed in hippocampal circuits (Barnes et al., 1977; Harris and Teyler, 1983; Dana and Martinez Jr., 1984; Raghavan et al., 1999; Chaudhury et al., 2005) and memory behavior (Chaudhury and Colwell, 2002; Eckel-Mahan and Storm,2009), perhaps suggesting similar molecular and cellular processes that are likely conserved (Gerstner and Yin, 2010). SCN LTP is observed maximally during the subjective light phase, at a time that correlates with higher cAMP levels and firing rate (Figure 3). Interestingly, high-frequency stimulation of the rat optic nerve induced SCN LTP that was inhibited by both NOS inhibitors or Ca2+/calmodulin kinase (CaMKII) inhibitors (Fukunaga et al., 2002). Further, SCN LTP induction correlated with increases in phosphorylation of CaMKII, MAPK, and CREB (Fukunaga et al., 2002), corroborating previous evidence which showed increases in CaMKII activation in the SCN following acute light exposure (Yokota et al., 2001). Importantly, SCN LTP was induced to a greater extent at times-of-day that were unable to alter phase-shifts in behavior. This may be predictable, since the clock is already “tuned” to have an elevated firing rate during this range of time (Figure 3). Therefore, changes in excitability could account for increases in LTP during the daytime, and a lack in the photic-stimulated phase-response. Further, Fukunaga et al. (2002) reported that they observed HFS-induced LTP during the night period, while their earlier report showed minimal induction (Nishikawa et al., 1995). An important difference between the two studies was that, as the authors noted, SCN slices were derived for a 12:12 LD cycle (Fukunaga et al., 2002) compared to “free-run” DD conditions in the previous study (Nishikawa et al., 1995). One possible explanation for the differences in results could revolve around the capacity of light to reinforce the underlying clock-mechanisms, establishing a “priming” effect that could potentially change the susceptibility of the neurons to changes in metaplasticity. Future studies determining the parameters in variations of light–dark periods with stimulation protocols to evoke SCN LTP and phase-response curves will be important before considering the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in generating circadian metaplasticity.

The SCN action potential firing rate is under circadian control (Green and Gillette, 1982; Welsh et al., 1995; Quintero et al., 2003; Meredith et al., 2006). The time-of-day changes in baseline firing rate could affect the sensitivity of time-of-day changes in cellular responsivity, network properties, and subsequent behavioral phase-shifts in response to light-stimulation. These changes, while metaplastic, could result from non-synaptic plasticity-related mechanism, such as spike timing-dependent plasticity or changes in neuronal excitability (Debanne and Poo, 2010), and still involve cAMP/MAPK/CREB signaling (Benito and Barco, 2010). These changes could provide a mechanism for a “permissive state” to allow synaptic modifications that would be necessary for long-lasting changes, analogous to those that are believed to be necessary for memory storage (Mozzachiodi and Byrne, 2010). Indeed, network organization appears to dictate the plasticity of phase shifting in the SCN (Schaap et al., 2003; Johnston et al., 2005; Rohling et al., 2006; Inagaki et al., 2007; vanderLeest et al., 2007; Naito et al., 2008), which can vary in capacity depending on the intrinsic photoperiod length (vanderLeest et al., 2009). Together, these data suggest that the synchronization of the SCN network can influence the ability of the circuits to adapt to changes in environmental stimuli. In addition to the underlying differences in molecular oscillators discussed earlier, differences in excitability of ion channels, versus LTP-related mechanisms, could provide some explanation for the observed changes in SCN period-length-dependent phase shifting (vanderLeest et al., 2009). What is clear is that time-of-day dependent changes exist in the response to photic input stimulation on network properties within the SCN, which translate to alteration in phase-response behavioral output (Figure 3). These metaplastic changes that are exhibited in the SCN may mirror those that are observed in higher-order network properties responsible for the memory trace, suggesting conservation of underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms for adaptive and long-term changes in neural firing and synaptic plasticity.

Conclusion

Basic timing mechanisms likely evolved to encode more complex plasticity-related processes, and a fundamental aspect is the ability to gate persistence from adaptation. How relevant environmental information is encoded in biology to form “memory” would have evolved using this principle, thereby establishing a metaplastic quality. The molecular mechanisms which appear to gate circadian metaplasticity likely involve the Ca2+ signaling, cGMP/PKG, and cAMP/MAPK/CREB cascades, and likely represent conserved regulators of both circadian rhythms and memory formation. The similarities between these systems offers an opportunity to study more simple models from which to further characterize the role of these molecules in the temporal gating that differentiates allocation from long-term storage (Won and Silva, 2008). Future work examining the role of these molecules, and how they relate to SCN period-length-dependent phase shifting, should provide fundamental information on basic nervous system function, and could prove to be a very useful model for examining how its networks integrate properties of excitability with metaplasticity (Jedlicka, 2002; Abraham, 2008) or other forms of plasticity, such as homeostatic plasticity (Nelson and Turrigiano, 2008).

Circadian molecules not previously implicated in synaptic plasticity or learning may be implicated in higher-order cognitive processes, and essential for memory allocation and/or storage. For example, how important are these clock gene pathways for the metaplasticity underlying the time-of-day changes in limbic- or cortical-dependent LTP or memory? Similarly, are molecules that are known to regulate metaplasticity and memory, such as PKMzeta (Drier et al., 2002; Sacktor, 2011; Sajikumar and Korte, 2011), able to regulate circadian rhythm plasticity? The hypothesis would predict that the mechanisms are likely shared, and therefore testable, especially in simple models, where similar functions are likely conserved. Drosophila is a unique animal model which offers the possibility to quickly study these questions. If LTP and metaplasticity exist in the SCN through similar mechanisms as the hippocampus of mammals, then this also predicts that LTP and metaplasticity should be observed in the clock cells of Drosophila (Figure 3). Since Drosophila also have well characterized phase-responses in circadian behavior to light manipulations (Rosato and Kyriacou, 2006), and conservation of most of the molecules involved in both circadian rhythms and memory formation (Gerstner and Yin, 2010), these questions are also testable, and have specific predictions based on what is known in other systems of higher-order species. Further, recent discoveries of the modulatory role of glial cells in plasticity-related processes and synaptic scaling (Panatier et al., 2006; Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006; Henneberger et al., 2010), cognitive and memory processes (Halassa et al., 2009; Halassa and Haydon, 2010; Florian et al., 2011; Suzuki et al., 2011), along with a role in circadian rhythms (Prolo et al., 2005; Suh and Jackson, 2007; Jackson, 2011; Marpegan et al., 2011; Ng et al., 2011), suggest that this cell type is in a unique position to integrate time-of-day dependent metaplasticity. While a considerable amount of progress has been made in elucidating components of the molecular clock, it is clear that a lot of work still remains in the field of circadian rhythms, and future study using it as a model from which to examine functional links between molecular, cellular, and circuit mechanisms, and how they contribute to metaplasticity and behavior should offer a wealth of information for more complex higher-order cognitive processes.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Allan Pack and the Center for Sleep and Circadian Neurobiology for support and to Kartik Ramamoorthi for useful discussions. Jason R. Gerstner is currently supported by NIH T32 HL07713.

References

- Abraham W. C. (2008). Metaplasticity: tuning synapses and networks for plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9 387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham W. C., Bear M. F. (1996). Metaplasticity: the plasticity of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 19 126–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agostino P. V., Ferreyra G. A., Murad A. D., Watanabe Y., Golombek D. A. (2004). Diurnal, circadian and photic regulation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the hamster suprachiasmatic nuclei. Neurochem. Int. 44 617–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akashi M., Hayasaka N., Yamazaki S., Node K. (2008). Mitogen-activated protein kinase is a functional component of the autonomous circadian system in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 28 4619–4623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir S., Beaule C., Arvanitogiannis A., Stewart J. (2002). Modes of plasticity within the mammalian circadian system. Prog. Brain Res. 138 191–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson S. E., Maywood E. S., Chesham J. E., Wozny C., Colwell C. S., Hastings M. H., Williams S. R. (2011). Cyclic AMP signaling control of action potential firing rate and molecular circadian pacemaking in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Biol. Rhythms 26 210–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aton S. J., Colwell C. S., Harmar A. J., Waschek J., Herzog E. D. (2005). Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide mediates circadian rhythmicity and synchrony in mammalian clock neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 8 476–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. A., McNaughton B. L., Goddard G. V., Douglas R. M., Adamec R. (1977). Circadian rhythm of synaptic excitability in rat and monkey central nervous system. Science 197 91–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass J., Takahashi J. S. (2011). Circadian rhythms: redox redux. Nature 469 476–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belle M. D., Diekman C. O., Forger D. B., Piggins H. D. (2009). Daily electrical silencing in the mammalian circadian clock. Science 326 281–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin M. P., Zhou H., Yin J. C. (1999). The Drosophila dCREB2 gene affects the circadian clock. Neuron 22 777–787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito E., Barco A. (2010). CREB’s control of intrinsic and synaptic plasticity: implications for CREB-dependent memory models. Trends Neurosci. 33 230–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienenstock E. L., Cooper L. N., Munro P. W. (1982). Theory for the development of neuron selectivity: orientation specificity and binocular interaction in visual cortex. J. Neurosci. 2 32–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S., Dove W., Herskowitz I., Thomas R. (1990). Genes and development: molecular and logical themes. Genetics 126 479–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao G., Nitabach M. N. (2008). Circadian control of membrane excitability in Drosophila melanogaster lateral ventral clock neurons. J. Neurosci. 28 6493–6501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury D., Colwell C. S. (2002). Circadian modulation of learning and memory in fear-conditioned mice. Behav. Brain Res. 133 95–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury D., Wang L. M., Colwell C. S. (2005). Circadian regulation of hippocampal long-term potentiation. J. Biol. Rhythms 20 225–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell C. S. (2011). Linking neural activity and molecular oscillations in the SCN. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 553–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comolli J., Taylor W., Hastings J. W. (1994). An inhibitor of protein phosphorylation stops the circadian oscillator and blocks light-induced phase shifting in Gonyaulax polyedra. J. Biol. Rhythms 9 13–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D. J., Haraura M., Reed H. E., Shen S., Sheward W. J., Morrison C. F., Marston H. M., Harmar A. J., Piggins H. D. (2003). The mouse VPAC2 receptor confers suprachiasmatic nuclei cellular rhythmicity and responsiveness to vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in vitro. Eur. J. Neurosci. 17 197–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dana R. C., Martinez J. L., Jr. (1984). Effect of adrenalectomy on the circadian rhythm of LTP. Brain Res. 308 392–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D., Poo M. M. (2010). Spike-timing dependent plasticity beyond synapse – pre- and post-synaptic plasticity of intrinsic neuronal excitability. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 2:21 10.3389/fnsyn. 2010.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jeu M., Hermes M., Pennartz C. (1998). Circadian modulation of membrane properties in slices of rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuroreport 9 3725–3729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J. M., Buchanan G. F., Tischkau S. A., Chen D., Kuriashkina L., Faiman L. E., Alster J. M., McPherson P. S., Campbell K. P., Gillette M. U. (1998). A neuronal ryanodine receptor mediates light-induced phase delays of the circadian clock. Nature 394 381–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J. M., Chen D., Weber E. T., Faiman L. E., Rea M. A., Gillette M. U. (1994). Resetting the biological clock: mediation of nocturnal circadian shifts by glutamate and NO. Science 266 1713–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J. M., Faiman L. E., Hurst W. J., Kuriashkina L. R., Gillette M. U. (1997). Resetting the biological clock: mediation of nocturnal CREB phosphorylation via light, glutamate, and nitric oxide. J. Neurosci. 17 667–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drier E. A., Tello M. K., Cowan M., Wu P., Blace N., Sacktor T. C., Yin J. C. (2002). Memory enhancement and formation by atypical PKM activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Neurosci. 5 316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan K. L., Phan T., Han S., Wang H., Chan G. C., Scheiner Z. S., Storm D. R. (2008). Circadian oscillation of hippocampal MAPK activity and cAmp: implications for memory persistence. Nat. Neurosci. 11 1074–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckel-Mahan K. L., Storm D. R. (2009). Circadian rhythms and memory: not so simple as cogs and gears. EMBO Rep. 10 584–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreyra G. A., Golombek D. A. (2001). Rhythmicity of the cGMP-related signal transduction pathway in the mammalian circadian system. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 280 R1348–R1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florian C., Vecsey C. G., Halassa M. M., Haydon P. G., Abel T. (2011). Astrocyte-derived adenosine and A1 receptor activity contribute to sleep loss-induced deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory in mice. J. Neurosci. 31 6956–6962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogle K. J., Parson K. G., Dahm N. A., Holmes T. C. (2011). CRYPTOCHROME is a blue-light sensor that regulates neuronal firing rate. Science 331 1409–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesen W. O., Block G. D. (1984). What is a biological oscillator? Am. J. Physiol. 246 R847–R853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga K., Horikawa K., Shibata S., Takeuchi Y., Miyamoto E. (2002). Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-dependent long-term potentiation in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus and its inhibition by melatonin. J. Neurosci. Res. 70 799–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstner J. R., Yin J. C. (2010). Circadian rhythms and memory formation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11 577–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginty D. D., Kornhauser J. M., Thompson M. A., Bading H., Mayo K. E., Takahashi J. S., Greenberg M. E. (1993). Regulation of CREB phosphorylation in the suprachiasmatic nucleus by light and a circadian clock. Science 260 238–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golombek D. A., Rosenstein R. E. (2010). Physiology of circadian entrainment. Physiol. Rev. 90 1063–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green D. J., Gillette R. (1982). Circadian rhythm of firing rate recorded from single cells in the rat suprachiasmatic brain slice. Brain Res. 245 198–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groos G., Hendriks J. (1982). Circadian rhythms in electrical discharge of rat suprachiasmatic neurones recorded in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 34 283–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa M. M., Florian C., Fellin T., Munoz J. R., Lee S. Y., Abel T., Haydon P. G., Frank M. G. (2009). Astrocytic modulation of sleep homeostasis and cognitive consequences of sleep loss. Neuron 61 213–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halassa M. M., Haydon P. G. (2010). Integrated brain circuits: astrocytic networks modulate neuronal activity and behavior. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72 335–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T., Liou S. Y., Fukushima T., Maruyama T., Watanabe S., Mikoshiba K., Ishida N. (1999a). The role of inositol trisphosphate-induced Ca2+ release from IP3-receptor in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus on circadian entrainment mechanism. Neurosci. Lett. 263 125–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada T., Niki T., Ziging P., Sugiyama T., Watanabe S., Mikoshiba K., Ishida N. (1999b). Differential expression patterns of inositol trisphosphate receptor types 1 and 3 in the rat suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. 838 131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmar A. J., Marston H. M., Shen S., Spratt C., West K. M., Sheward W. J., Morrison C. F., Dorin J. R., Piggins H. D., Reubi J. C., Kelly J. S., Maywood E. S., Hastings M. H. (2002). The VPAC(2) receptor is essential for circadian function in the mouse suprachiasmatic nuclei. Cell 109 497–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris K. M., Teyler T. J. (1983). Age differences in a circadian influence on hippocampal LTP. Brain Res. 261 69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays J. D., Imbrie J., Shackleton N. J. (1976). Variations in the earth’s orbit: pacemaker of the ice ages. Science 194 1121–1132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C., Papouin T., Oliet S. H., Rusakov D. A. (2010). Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature 463 232–236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M. (2004). Calcium dynamics and circadian rhythms in suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuroscientist 10 315–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda M., Sugiyama T., Wallace C. S., Gompf H. S., Yoshioka T., Miyawaki A., Allen C. N. (2003). Circadian dynamics of cytosolic and nuclear Ca2+ in single suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neuron 38 253–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inagaki N., Honma S., Ono D., Tanahashi Y., Honma K. (2007). Separate oscillating cell groups in mouse suprachiasmatic nucleus couple photoperiodically to the onset and end of daily activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 7664–7669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri J. N., Michel S., Vansteensel M. J., Meijer J. H., Colwell C. S. (2005). Fast delayed rectifier potassium current is required for circadian neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8 650–656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itri J. N., Vosko A. M., Schroeder A., Dragich J. M., Michel S., Colwell C. S. (2010). Circadian regulation of a-type potassium currents in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurophysiol. 103 632–640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacklet J. W. (1977). Neuronal circadian rhythm: phase shifting by a protein synthesis inhibitor. Science 198 69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson F. R. (2011). Glial cell modulation of circadian rhythms. Glia 59 1341–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jedlicka P. (2002). Synaptic plasticity, metaplasticity and BCM theory. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 103 137–143 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J. D., Ebling F. J., Hazlerigg D. G. (2005). Photoperiod regulates multiple gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei and pars tuberalis of the Siberian hamster (Phodopus sungorus). Eur. J. Neurosci. 21 2967–2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent J., Meredith A. L. (2008). BK channels regulate spontaneous action potential rhythmicity in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. PLoS ONE 3 e3884. 10.1371/journal.pone. 0003884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. Y., Choi H. J., Kim J. S., Kim Y. S., Jeong D. U., Shin H. C., Kim M. J., Han H. C., Hong S. K., Kim Y. I. (2005). Voltage-gated calcium channels play crucial roles in the glutamate-induced phase shifts of the rat suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Eur. J. Neurosci. 21 1215–1222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitayama Y., Nishiwaki T., Terauchi K., Kondo T. (2008). Dual KaiC-based oscillations constitute the circadian system of cyanobacteria. Genes Dev. 22 1513–1521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko G. Y., Shi L., Ko M. L. (2009). Circadian regulation of ion channels and their functions. J. Neurochem. 110 1150–1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kononenko N. I., Kuehl-Kovarik M. C., Partin K. M., Dudek F. E. (2008). Circadian difference in firing rate of isolated rat suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons. Neurosci. Lett. 436 314–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornhauser J. M., Nelson D. E., Mayo K. E., Takahashi J. S. (1990). Photic and circadian regulation of c-fos gene expression in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuron 5 127–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlman S. J., McMahon D. G. (2004). Rhythmic regulation of membrane potential and potassium current persists in SCN neurons in the absence of environmental input. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20 1113–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmesser S., Franken P., Feil S., Emmenegger Y., Albrecht U., Feil R. (2009). cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I is implicated in the regulation of the timing and quality of sleep and wakefulness. PLoS ONE 4 e4238 10.1371/journal. pone.0004238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marpegan L., Swanstrom A. E., Chung K., Simon T., Haydon P. G., Khan S. K., Liu A. C., Herzog E. D., Beaule C. (2011). Circadian regulation of ATP release in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 31 8342–8350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur A., Golombek D. A., Ralph M. R. (1996). cGMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitors block light-induced phase advances of circadian rhythms in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. 270 R1031–R1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maywood E. S., Reddy A. B., Wong G. K., O’Neill J. S., O’Brien J. A., McMahon D. G., Harmar A. J., Okamura H., Hastings M. H. (2006). Synchronization and maintenance of timekeeping in suprachiasmatic circadian clock cells by neuropeptidergic signaling. Curr. Biol. 16 599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh B. E., Hogenesch J. B., Bradfield C. A. (2010). Mammalian Per-Arnt-Sim proteins in environmental adaptation. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 72 625–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith A. L., Wiler S. W., Miller B. H., Takahashi J. S., Fodor A. A., Ruby N. F., Aldrich R. W. (2006). BK calcium-activated potassium channels regulate circadian behavioral rhythms and pacemaker output. Nat. Neurosci. 9 1041–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohawk J. A., Takahashi J. S. (2011). Cell autonomy and synchrony of suprachiasmatic nucleus circadian oscillators. Trends Neurosci. 34 349–358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. Y., Speh J. C. (1993). GABA is the principal neurotransmitter of the circadian system. Neurosci. Lett. 150 112–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozzachiodi R., Byrne J. H. (2010). More than synaptic plasticity: role of nonsynaptic plasticity in learning and memory. Trends Neurosci. 33 17–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahm S. S., Farnell Y. Z., Griffith W., Earnest D. J. (2005). Circadian regulation and function of voltage-dependent calcium channels in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 25 9304–9308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito E., Watanabe T., Tei H., Yoshimura T., Ebihara S. (2008). Reorganization of the suprachiasmatic nucleus coding for day length. J. Biol. Rhythms 23 140–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M., Imai K., Ito H., Nishiwaki T., Murayama Y., Iwasaki H., Oyama T., Kondo T. (2005). Reconstitution of circadian oscillation of cyanobacterial KaiC phosphorylation in vitro. Science 308 414–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson S. B., Turrigiano G. G. (2008). Strength through diversity. Neuron 60 477–482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng F. S., Tangredi M. M., Jackson F. R. (2011). Glial cells physiologically modulate clock neurons and circadian behavior in a calcium-dependent manner. Curr. Biol. 21 625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa Y., Shibata S., Watanabe S. (1995). Circadian changes in long-term potentiation of rat suprachiasmatic field potentials elicited by optic nerve stimulation in vitro. Brain Res. 695 158–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K., Impey S., Smith D., Athos J., Storm D. R. (1999). Circadian regulation of cAMP response element-mediated gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. J. Biol. Chem. 274 17748–17756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrietan K., Impey S., Storm D. R. (1998). Light and circadian rhythmicity regulate MAP kinase activation in the suprachiasmatic nuclei. Nat. Neurosci. 1 693–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. S., Maywood E. S., Chesham J. E., Takahashi J. S., Hastings M. H. (2008). cAMP-dependent signaling as a core component of the mammalian circadian pacemaker. Science 320 949–953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. S., Reddy A. B. (2011). Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature 469 498–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill J. S., van Ooijen G., Dixon L. E., Troein C., Corellou F., Bouget F. Y., Reddy A. B., Millar A. J. (2011). Circadian rhythms persist without transcription in a eukaryote. Nature 469 554–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster H., Werner C., Magnone M. C., Mayser H., Feil R., Seeliger M. W., Hofmann F., Albrecht U. (2003). cGMP-dependent protein kinase II modulates mPer1 and mPer2 gene induction and influences phase shifts of the circadian clock. Curr. Biol. 13 725–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A., Theodosis D. T., Mothet J. P., Touquet B., Pollegioni L., Poulain D. A., Oliet S. H. (2006). Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell 125 775–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panda S., Hogenesch J. B., Kay S. A. (2002). Circadian rhythms from flies to human. Nature 417 329–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paranjpe D. A., Sharma V. K. (2005). Evolution of temporal order in living organisms. J. Circadian Rhythms 3 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennartz C. M., de Jeu M. T., Bos N. P., Schaap J., Geurtsen A. M. (2002). Diurnal modulation of pacemaker potentials and calcium current in the mammalian circadian clock. Nature 416 286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan T. X., Chan G. C., Sindreu C. B., Eckel-Mahan K. L., Storm D. R. (2011). The diurnal oscillation of MAP (mitogen-activated protein) kinase and adenylyl cyclase activities in the hippocampus depends on the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 31 10640–10647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittendrigh C. S. (1993). Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 55 16–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prolo L. M., Takahashi J. S., Herzog E. D. (2005). Circadian rhythm generation and entrainment in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 25 404–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser R. A., Gillette M. U. (1989). The mammalian circadian clock in the suprachiasmatic nuclei is reset in vitro by cAMP. J. Neurosci. 9 1073–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosser R. A., McArthur A. J., Gillette M. U. (1989). cGMP induces phase shifts of a mammalian circadian pacemaker at night, in antiphase to cAMP effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 86 6812–6815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero J. E., Kuhlman S. J., McMahon D. G. (2003). The biological clock nucleus: a multiphasic oscillator network regulated by light. J. Neurosci. 23 8070–8076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan A. V., Horowitz J. M., Fuller C. A. (1999). Diurnal modulation of long-term potentiation in the hamster hippocampal slice. Brain Res. 833 311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohling J., Wolters L., Meijer J. H. (2006). Simulation of day-length encoding in the SCN: from single-cell to tissue-level organization. J. Biol. Rhythms 21 301–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosato E., Kyriacou C. P. (2006). Analysis of locomotor activity rhythms in Drosophila. Nat. Protoc. 1 559–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacktor T. C. (2011). How does PKMzeta maintain long-term memory? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 12 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S., Korte M. (2011). Metaplasticity governs compartmentalization of synaptic tagging and capture through brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and protein kinase Mzeta (PKMzeta). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 2551–2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanada K., Okano T., Fukada Y. (2002). Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and negatively regulates basic helix-loop-helix-PAS transcription factor BMAL1. J. Biol. Chem. 277 267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaap J., Albus H., vanderLeest H. T., Eilers P. H., Detari L., Meijer J. H. (2003). Heterogeneity of rhythmic suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons: implications for circadian waveform and photoperiodic encoding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 15994–15999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V., Gu H., Sharma V. K., O’Dowd D. K., Holmes T. C. (2008). Circadian- and light-dependent regulation of resting membrane potential and spontaneous action potential firing of Drosophila circadian pacemaker neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 99 976–988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellwagen D., Malenka R. C. (2006). Synaptic scaling mediated by glial TNF-alpha. Nature 440 1054–1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh J., Jackson F. R. (2007). Drosophila ebony activity is required in glia for the circadian regulation of locomotor activity. Neuron 55 435–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A., Stern S. A., Bozdagi O., Huntley G. W., Walker R. H., Magistretti P. J., Alberini C. M. (2011). Astrocyte-neuron lactate transport is required for long-term memory formation. Cell 144 810–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessmar-Raible K., Raible F., Arboleda E. (2011). Another place, another timer: marine species and the rhythms of life. Bioessays 33 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkau S. A., Gallman E. A., Buchanan G. F., Gillette M. U. (2000). Differential cAMP gating of glutamatergic signaling regulates long-term state changes in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. J. Neurosci. 20 7830–7837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita J., Nakajima M., Kondo T., Iwasaki H. (2005). No transcription–translation feedback in circadian rhythm of KaiC phosphorylation. Science 307 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanderLeest H. T., Houben T., Michel S., Deboer T., Albus H., Vansteensel M. J., Block G. D., Meijer J. H. (2007). Seasonal encoding by the circadian pacemaker of the SCN. Curr. Biol. 17 468–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanderLeest H. T., Rohling J. H., Michel S., Meijer J. H. (2009). Phase shifting capacity of the circadian pacemaker determined by the SCN neuronal network organization. PLoS ONE 4 e4976 10.1371/journal.pone.0004976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Gall C., Duffield G. E., Hastings M. H., Kopp M. D., Dehghani F., Korf H. W., Stehle J. H. (1998). CREB in the mouse SCN: a molecular interface coding the phase-adjusting stimuli light, glutamate, PACAP, and melatonin for clockwork access. J. Neurosci. 18 10389–10397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber E. T., Gannon R. L., Rea M. A. (1995). cGMP-dependent protein kinase inhibitor blocks light-induced phase advances of circadian rhythms in vivo. Neurosci. Lett. 197 227–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh D. K., Logothetis D. E., Meister M., Reppert S. M. (1995). Individual neurons dissociated from rat suprachiasmatic nucleus express independently phased circadian firing rhythms. Neuron 14 697–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won J., Silva A. J. (2008). Molecular and cellular mechanisms of memory allocation in neuronetworks. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 89 285–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Isejima H., Matsuo T., Okura R., Yagita K., Kobayashi M., Okamura H. (2003). Synchronization of cellular clocks in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Science 302 1408–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S., Yamamoto M., Moriya T., Akiyama M., Fukunaga K., Miyamoto E., Shibata S. (2001). Involvement of calcium-calmodulin protein kinase but not mitogen-activated protein kinase in light-induced phase delays and Per gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hamster. J. Neurochem. 77 618–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Takahashi J. S., Turek F. W. (1996). Critical period for cycloheximide blockade of light-induced phase advances of the circadian locomotor activity rhythm in golden hamsters. Brain Res. 740 285–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]