Abstract

Whole body vibration (WBV) has been suggested to elicit reflex muscle contractions but this has never been verified. We recorded from 32 single motor units (MU) in the vastus lateralis of 7 healthy subjects (34 ± 15.4 yr) during five 1-min bouts of WBV (30 Hz, 3 mm peak to peak), and the vibration waveform was also recorded. Recruitment thresholds were recorded from 38 MUs before and after WBV. The phase angle distribution of all MUs during WBV was nonuniform (P < 0.001) and displayed a prominent peak phase angle of firing. There was a strong linear relationship (r = −0.68, P < 0.001) between the change in recruitment threshold after WBV and average recruitment threshold; the lowest threshold MUs increased recruitment threshold (P = 0.008) while reductions were observed in the higher threshold units (P = 0.031). We investigated one possible cause of changed thresholds. Presynaptic inhibition in the soleus was measured in 8 healthy subjects (29 ± 4.6 yr). A total of 30 H-reflexes (stimulation intensity 30% Mmax) were recorded before and after WBV: 15 conditioned by prior stimulation (60 ms) of the antagonist and 15 unconditioned. There were no significant changes in the relationship between the conditioned and unconditioned responses. The consistent phase angle at which each MU fired during WBV indicates the presence of reflex muscle activity similar to the tonic vibration reflex. The varying response in high- and low-threshold MUs may be due to the different contributions of the mono- and polysynaptic pathways but not presynaptic inhibition.

Keywords: recruitment threshold, tonic vibration reflex, monosynaptic, polysynaptic, fine wire EMG

whole body vibration (WBV) is an increasingly popular means of exercise due to reports of improved strength, power, balance, and bone strength (11, 14). The mechanisms responsible for elevated muscle activity during WBV and performance enhancement afterwards remain unclear, and reflex muscular contractions, damping, or postural control mechanisms have all been proposed (1, 10, 48). It is unlikely that hypertrophy occurs after WBV (32), and this suggests that any change may be caused by neural mechanisms such as altered motoneuron (MN) excitability, synergist and antagonist coactivation, spindle sensitivity, motor unit (MU) recruitment thresholds, and synchronization (10, 35). Currently there is no direct evidence for any of these hypotheses, which may be due to excitatory inflow to the MN, a facilitatory effect on the gamma system due to sensory stimulation, or potentially an increase in the excitatory state of central and peripheral structures (10).

Locally applied vibration causes the primary endings of muscle spindles to respond in a 1:1 manner, potentially up to 180 Hz, phase locked with the frequency of vibration (38, 39). Secondary endings are generally thought to be less sensitive to vibration (2, 6, 30, 38) and respond in a similar manner at lower frequencies (7). When the maximum discharge rate is reached, any further increase in vibration frequency tends to cause the receptor to fire at a subharmonic of that frequency (7, 38). Golgi tendon organs are also sensitive to locally applied vibration but possibly to a lesser extent than primary and secondary endings (7, 9, 20). Although afferents can respond to vibration in a 1:1 manner at high frequencies (6, 7, 30, 38), the efferent response is limited to discharge frequencies of <25 Hz (8, 18, 25, 40). This results in a tonic vibration reflex (TVR) occurring mostly at frequencies >10 Hz (19, 40) with each MU having a minimal frequency threshold after which there is a rapid increase to maximum discharge rate (18). This discharge is phase locked to the vibration cycle, although at frequencies >150 Hz the normal variability (“jitter”) in their latency makes it difficult to determine if this is the case (8, 18, 25, 40). It has also been found that there is considerable variability between MUs in the phase of the cycle that they fire (8, 25), indicating they do not all fire simultaneously.

The most frequently cited mechanism by which WBV increases muscle activity is the TVR (10, 43, 45), although there is no conclusive evidence that this occurs. As highlighted by Rittweger et al. (36), the TVR is generally elicited at higher frequencies (>100 Hz) by vibration of a single muscle/tendon and may be suppressed by voluntary movements (9, 19) and enhanced by muscle stretch and low level contractions (9, 19). WBV is performed at <50 Hz and often simultaneously with voluntary exercise so it is debatable whether the TVR is elicited, particularly as many muscles and tendons in the lower limbs are vibrated. Increased EMG activity during WBV has been reported (1, 12, 43) but the need to filter signals to remove motion artifact at the vibration frequency (1, 21) makes it impossible to determine if the TVR occurs. If it does, the MUs would be expected to fire at a similar point in the vibration cycle.

As hypertrophy is unlikely to occur from WBV, it has been suggested that neural adaptations are responsible for any improvements seen (10) but many proposed mechanisms are based on work with locally applied vibration. One such study found that MU recruitment thresholds were lower during vibration than during voluntary contractions and that a short (20 s) bout reduced recruitment thresholds immediately afterward (41). If the TVR were to occur during WBV, then a reduction in MU recruitment thresholds may be observed. During locally applied vibration it has been noted that prolonged vibration (>1 min) during a muscle contraction can reduce MU firing rates while simultaneously eliciting the TVR (4). A possible mechanism for this is thought to be presynaptic inhibition of the Ia terminals. If this were the case, then it is possible that recruitment thresholds after WBV may in fact be increased.

The aims of this study were to determine whether the firing of single MUs were phase locked to the cycle of WBV and also if recruitment threshold was affected by WBV. It was hypothesized that MU firing would be phase locked to vibration and that recruitment thresholds would be reduced after WBV. A further aim was to assess the levels of presynaptic inhibition before and after WBV.

METHODS

Subjects

We investigated MU recruitment threshold before and after WBV and also the firing patterns of single units during WBV in three related experiments. Experiment 1: firing patterns were recorded from 32 single MUs (1–7 MUs per subject) during WBV in 7 subjects (age 34 ± 15.4 yr; height 1.74 ± 0.06 m; mass 73.2 ± 8.5 kg; mean ± SD). Experiment 2: threshold recordings were obtained from 38 single MUs (2–9 MUs per subject) in the same subjects before and after WBV. Experiment 3: an additional 8 subjects (age 29 ± 4.6 yr; height 1.72 ± 0.08 m; mass 70 ± 12.3; 3 of whom performed the first set of experiments) performed follow-up testing to investigate the effect of WBV on presynaptic inhibition. Subjects had no known neurological or musculoskeletal disorders and none were known to be pregnant. Approval from the local Research Ethics Committee was obtained, and subjects gave written informed consent prior to participation.

Experiment 1: Firing Patterns from Single MUs During WBV

Intramuscular EMG.

Single MU recordings were obtained from the vastus lateralis (VL) muscle using stainless steel wires insulated to within 2 mm of the tip (disposable paired fine wire EMG needle electrodes, Chalgren Enterprises) that were inserted into the muscle belly ∼1–2 cm beyond the muscle fascia using a 3 cm 27-gauge hypodermic needle that was then withdrawn. A line running 5 cm anterior to the line between the greater trochanter and the lateral femoral epicondyle was marked on the skin. Four wires were inserted, at the midpoint, 4 cm below this level and 4 and 8 cm above the midpoint. Shaving and swabbing with alcohol wipes of the insertion area was performed prior to placement. A reference surface electrode was placed over the lateral aspect of the patella.

Fine wires were interfaced with a preamplifier using a custom-built adaptor in which the wire was connected to a tightly wound spring. Signals were amplified by ×100 or ×1,000 and sampled at 20 kHz with the CED1401 (Cambridge Electronic Design Limited, Cambridge, UK and stored on a personal computer).

WBV.

Five 1-min bouts of WBV were performed with 30 s of rest between each at a frequency and amplitude of 30 Hz and 3 mm peak to peak, respectively (Galileo 2000, Novotec Medical). The subjects were barefoot and stood upright without locking their knees. A strain gauge placed on the platform recorded the motion of the platform, which was digitized (2000 Hz; CED1401) and stored on a computer. Intramuscular EMG and the platform motion were recorded simultaneously throughout the vibration period. This amplitude of WBV was selected as it was noted during pilot work that at higher amplitudes significant motion artifact and movement of the electrodes occurred. This was also the case when electrodes were positioned in more distal muscles. As recording the recruitment threshold relies on identifying the same MU before and after vibration, it was decided to test the VL at a low amplitude. Even with this, however, recruitment thresholds of the same MU before and after WBV could only be recorded with confidence in 16 of 28 electrodes.

Experiment 2: Threshold Recordings from Single MUs Before and After WBV

Dynamometer.

MU recruitment thresholds were identified prior to and immediately after WBV three times with 1 min of rest between each. Subjects performed ramp quadriceps contractions, gradually increasing the force by 0.5 N/s. The rate of force increase was controlled using visual feedback from the dynamometer displayed on a computer screen at the subjects' eye level, using the analog force trace and the numerically displayed actual force. Force was increased to the point where it was no longer possible to identify single MUs. During all contractions, force and intramuscular EMG were recorded simultaneously. Before being tested, subjects familiarized themselves with performing a ramp contraction.

Force measurement.

Isometric force recordings were obtained from the quadriceps muscle using a dynamometer (KinCom 125AP, Chattanooga Group, Chattanooga, TN). Subjects were seated with their knee and hip at 90° while the axis of rotation of the dynamometer was aligned the lateral femoral epicondyle and the lever arm secured ∼3 cm proximal to the lateral malleolus. To minimize movement and contribution of other muscles, the subject was strapped to the dynamometer by a belt over the pelvis. The force was digitized (2,000 Hz, CED 1401) and stored on a computer for subsequent offline analysis.

Experiment 3: Effect of WBV on Presynaptic Inhibition

Surface EMG.

EMG recordings (Delsys, Boston, MA) were obtained from the soleus muscle. The recording electrode (DE-2.1 single differential electrodes, Delsys) was placed over the soleus two-thirds of the way along a line from the medial condyle of the femur to the medial malleolus. The reference electrode was placed over the lateral aspect of the knee. Prior to electrode placement the skin was shaved, lightly abraded, and cleaned with alcohol wipes. The electrodes were fixed to the skin with double-sided adhesive and 3M Micropore tape.

EMG was sampled at a frequency of 2,000 Hz, digitized (CED 140), and displayed on a computer. The signal was recorded with a gain of 1,000× and band pass filtered between 20 to 450 Hz (Bagnoli, Delsys).

Electrical Stimulation

Electrical stimulation was applied by a constant current stimulator (Digitimer Stimulator DS7, Digitimer, UK). H-reflexes were elicited through stimulation (duration 0.5 ms) of the tibial nerve. The cathode was placed over the nerve in the popliteal fossa while the anode was positioned over the patella. Once the H-reflex was elicited, the maximum amplitude (peak to peak) of the M wave (Mmax) was determined. Throughout the remainder of the testing, the intensity of stimulation was set at a level that elicited an H-reflex that was 30% of Mmax as this has been used by other authors (15, 26).

A conditioning stimulus was delivered to the common peroneal nerve at the level of the caput fibulae. This consisted of a train of three impulses, delivered at 300 Hz, of 0.5-ms duration at an intensity of 1.3 times motor threshold. The interval between the conditioning stimulus and the test stimulus was 60 ms. Once electrode position and the stimulation intensities had been determined, the electrodes were secured with a Velcro strap and a bandage to minimize movement throughout testing.

Protocol

During testing, subjects sat upright in a comfortable chair with arm rests in a quiet room. Their feet were supported in ∼10° of plantarflexion with the knee in 60° of flexion. They were instructed to remain still during testing and to refrain from moving their head and talking. Fifteen alternating unconditioned and conditioned (30 total) reflexes were elicited at a frequency of 0.125 Hz. Subjects then performed WBV using the same protocol as detailed above. Immediately after WBV subjects were repositioned in the seat and conditioned and unconditioned reflexes were recorded. This was repeated 10 and 20 min after WBV.

The average peak to peak amplitude of the 15 conditioned and unconditioned H-reflexes were determined for each time point. The conditioned reflexes were expressed as a percentage of the unconditioned reflex, thus estimating how much the test reflex is reduced by presynaptic inhibition.

Data Analysis

MU firing patterns during WBV.

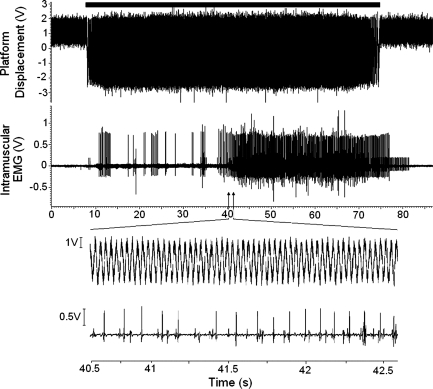

Intramuscular EMG recordings obtained during WBV (an example of which is shown in Fig. 1) were band pass filtered (100–5,000 Hz, 4th order Butterworth, Spike 2 v Cambridge Electronic Design Limited 6.12) after DC offset removal and visual inspection to determine if a single MU could be identified. The MU discrimination procedure described in the following section was performed on any identifiable MU and the time at which it fired was recorded. The firing time of each MU along with the motion signal recorded from the platform were exported to MATLAB (version 7, The Mathworks, Natick, MA) for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

Intramuscular EMG recording obtained during a 1-min period of whole body vibration (WBV). Top trace shows the motion of the WBV platform, the black bar above this represents the period where the platform is turned on. Middle traces shows the intramuscular EMG recorded during WBV. Bottom section shows a period of 2 s during WBV where individual motor units (MUs) can be identified.

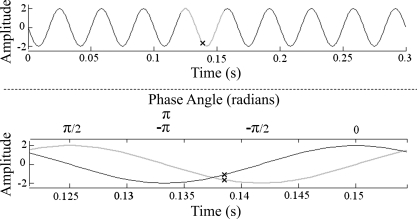

The motion signal recorded from the platform was filtered with a fourth order low-pass Butterworth filter (cut off frequency 60 Hz). The time at which each MU fired was identified on the motion signal and an equal portion before and after this, representing one complete cycle of vibration, was selected for analysis (Fig. 2). During three of the test sessions the strain gauge moved during WBV, saturating the signal and causing the top of the signal to be “clipped.” To overcome this, a sine wave corresponding to the frequency of vibration was artificially generated and its phase was shifted until the highest correlation with the original signal was found. This signal was then integrated to generate a cosine wave of the same amplitude. The amplitude (A) of each of these waves at the point where the MU fired was determined (Ax from cosine wave and Ay from the sine wave; Fig. 2). The phase (P) of the sine wave at which the MU fired was then determined using the two argument arctangent function:

Fig. 2.

Process for identifying the phase of vibration at which the MU fired. Top: motion of the platform during WBV. Equal portions of the data selected before and after the point where the MU fired (X on the top trace) representing 1 cycle of the sine wave. Bottom: artificially generated sine wave (gray) corresponding to the selected portion and the cosine wave (black) generated by integrating the sine wave. Ax and Ay are represented by the X on the cosine and sine wave, respectively.

The phase angle was calculated in radians and ranged from 0 to ±π, with zero representing the point where the sine wave crosses the x-axis from negative to positive.

MU recruitment threshold before and after WBV.

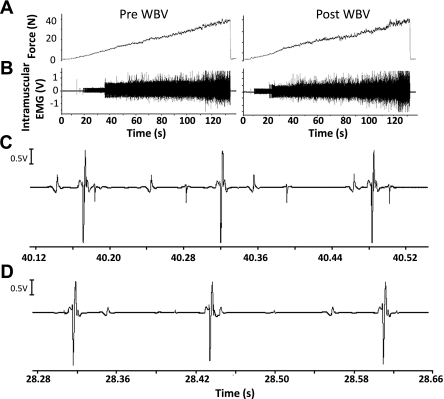

Discrimination of a single MU potential was performed offline by visual inspection and by using the template matching features of Spike 2 (version 6.12). The recruitment threshold of each MU was identified as the force at which the first potential appeared and was followed by a steady discharge rate for the remainder of the contraction where the interspike interval coefficient of variation of the first five spikes was <20%. The average MU recruitment threshold of the three ramp contractions was used for analysis (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Intramuscular EMG recording during recruitment threshold task before and after WBV. A: force recorded during recruitment threshold task. B: intramuscular EMG recording showing a greater number of MUs firing at higher levels of force. C: expanded section showing the intramuscular EMG recording before WBV. D: expanded section showing the intramuscular EMG recording after WBV.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v 16 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) and STATA v 11.1 (StataCorp).

MU firing during WBV was assessed using circular statistics. The mean phase angle of each MU during WBV was calculated. Rayleigh's test, which tests the null hypothesis that the distribution of points on a circle is uniform, was used to determine whether a single MU fired at the same phase of vibration. To test whether there was a significant difference in phase angle between subjects the Mardia-Wheeler-Watson test was used. Significance was set at P < 0.05 in all cases.

A paired t-test was performed to determine if there was any difference in MU recruitment thresholds before and after WBV. Pearson's correlation coefficient was calculated to determine if there was a relationship between MU recruitment threshold and the change in threshold.

The levels of presynaptic inhibition were found to be not normally distributed. Friedman's ANOVA was performed to determine if there was any significant difference in levels of presynaptic inhibition before and after WBV.

RESULTS

MU Firing Patterns During WBV

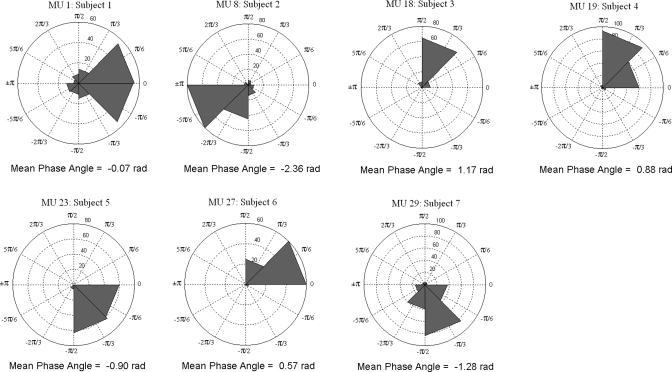

Data from each MU were displayed on a rose plot. Each phase angle was plotted on a circular histogram ranging from 0 to ±π radians, and the number of phase angles within each bin is identified on the circumference of each inner axis. Figure 4 depicts a rose plot of a single MU obtained from each subject showing the phase during WBV in which it fired and the mean phase angle (for plots of all MUs see supplementary data online). Rayleigh's test revealed that the phase at which the MU fired during WBV was not uniform (P < 0.001 for all MUs), indicating that the phase at which a single MU fired was the same throughout WBV, as evidenced by distinct peaks occurring in each rose plot. The Mardia-Wheeler-Watson test indicated that the phase at which each MU fired between subjects was significantly different (P = 0.023).

Fig. 4.

Rose plot of the phase angles recorded during WBV. The direction of each bin in the rose plot indicates the phase angle at which that MU fired. The number of firings within a given bin are indicated on the inner circles of the rose plot. Displayed is a single MU selected from each subject (remaining MUs can be found in the online supplementary data, different colors represent each subject).

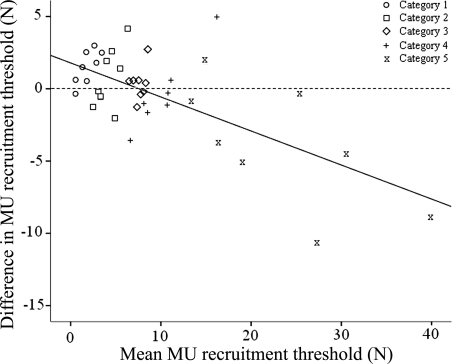

MU Recruitment Threshold

The mean rate of force rise of the trials prior to WBV was 0.44 N/s, which was no different than that of the trials after WBV (0.47 N/s; P = 0.604). When all MUs were analyzed together there was no significant difference in MU recruitment threshold before and after WBV (P > 0.05). A strong relationship (r = −0.68, P < 0.001; Fig. 5) was observed between the average recruitment threshold (i.e., average pre and post WBV recruitment threshold) and the change in threshold such that higher threshold MUs exhibited a greater reduction. To explore this relationship further the data were grouped into five categories (determined using the Freidmann-Diaconis rule) based on the initial recruitment threshold (category 1 was the lowest and category 5 was the highest; Fig. 5). Thresholds in category 1 MUs increased after WBV (P = 0.008). There was no change in recruitment thresholds after WBV in categories 2, 3, and 4 units (P > 0.05). Threshold significantly declined in category 5 units after WBV (P = 0.031; Table 1).

Fig. 5.

Mean MU recruitment threshold (of all pre- and post recruitment thresholds) plotted against the change in threshold before and after WBV. The trend line indicates a strong linear relationship between recruitment threshold and change in recruitment threshold (r = −0.68, P < 0.001). The shape of each point indicates the category in which the MU was placed for subsequent analysis (categories were based on the pre-WBV recruitment threshold resulting in overlap of some categories in figure).

Table 1.

MU recruitment thresholds

| Initial Recruitment Threshold | Before WBV | After WBV |

|---|---|---|

| Category 1 | 1.08 ± 0.74 | 2.60 ± 1.56* |

| Category 2 | 3.79 ± 1.14 | 4.07 ± 1.60 |

| Category 3 | 7.44 ± 0.73 | 7.81 ± 1.05 |

| Category 4 | 10.42 ± 1.84 | 10.13 ± 4.37 |

| Category 5 | 25.40 ± 10.59 | 21.34 ± 7.76† |

Recruitment threshold (N, mean ± SD) before and after whole body vibration (WBV) of motor units (MUs) categorized by their initial threshold.

Significantly greater recruitment threshold after WBV (P = 0.008).

Significantly lower recruitment thresholds after WBV (P = 0.031).

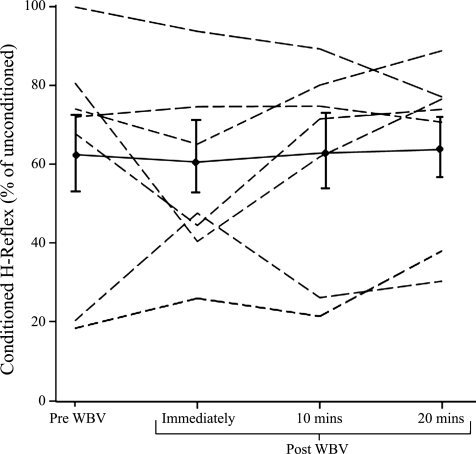

Presynaptic Inhibition

There was considerable individual variation in the level of presynaptic inhibition (Fig. 6), but overall there was no significant difference between the levels of presynaptic inhibition before and after WBV (P = 0.93).

Fig. 6.

Levels of presynaptic inhibition for each subject before, immediately, 10, and 20 min after WBV. The line with ● and error bars represents the mean (SE) level of presynaptic inhibition for all subjects.

DISCUSSION

This study succeeded in recording the activity of single MUs during WBV. The relationship of their activity to the phase of the vibration cycle was not uniform but displayed a peak, suggesting that MU firing is phase locked to the vibration cycle. This could indicate that activity is reflexive, although the timing varied between subjects, possibly due to differing damping mechanisms. There was a strong relationship between MU recruitment threshold and change in threshold such that increases in recruitment threshold were observed in the lowest threshold MUs while decreases occurred in highest threshold MUs. Presynaptic inhibition was unaffected by WBV and therefore unlikely to be involved in the changes found.

WBV has been suggested to elicit the TVR, although there has not been direct evidence for this (10, 45). If increases in muscle activity (1, 32) were primarily due to postural control mechanisms or the subject voluntarily contracting their muscles, MU firing would occur randomly throughout the vibration cycle. If, however, muscle activity was reflexive, MU firing would be phase locked to the vibration cycle as with locally applied vibration (8, 18, 25, 40). All 32 MUs identified during WBV exhibited this type of firing with a clear peak phase angle being observed.

It appeared that no MU fired in consecutive vibration cycles, indicating that the firing frequency was not driven in a 1:1 fashion, although this was not calculated due to movement artifact from the platform and multiple MUs firing. As MU discharge was related to the vibration cycle and the 30-Hz vibration used would be expected to result in a continual discharge of Ia afferents (6, 7, 30, 38), these data support the suggestion that the input responsible for timing MU discharge retains a pulsatile quality (8). For each MU, the variation in the timing (“jitter”) of firing was determined based on the 95% confidence limits and ranged between 0.5 and 4.1 ms for all MUs. Low levels of jitter have been suggested to indicate that monosynaptic activation of Ia afferents plays an important role in the triggering of the MU (8, 18, 29); this, however, does not exclude the influence of polysynaptic pathways.

The TVR has a slow onset and decline (19), can be controlled voluntarily, and is susceptible to anesthetic drugs (9, 25, 28), all of which are indicative of a polysynaptic contribution. Slow MUs are mostly activated by monosynaptic pathways while fast ones are activated by mono- and polysynaptic pathways (40). It is likely that during WBV, low-threshold MUs were predominantly recorded. These would correspond to slow-twitch MUs and could explain why, despite the fact that mono- and polysynaptic pathways play a role in the TVR, MU firing was phase locked to vibration. It is also possible that the units showing higher levels of jitter may represent faster ones, although firing related to background activity to maintain posture cannot be ruled out.

The phase at which MUs fired varied between subjects, although this usually occurred in the upward portion of the vibration cycle, in agreement with studies of locally applied vibration on the lower limbs (8). Differences in lower limb length of each subject may account for this due to the time taken to travel around the reflex arc. Whether the phase of the platform vibration can be taken to represent the phase of vibration experienced at the patella tendon and VL, which determine the response of the MUs studied, must also be considered. There is a phase lag between the platform vibration and that experienced throughout the body (5), possibly as a result of tissue characteristics, muscle activity, and the distance from the platform; it is therefore reasonable to assume that the phase of vibration at the knee is different to that at the platform. Although subjects were requested to stand with even weight distribution between the fore and hind foot this may not have occurred. Placing more weight on the heel could increase transmission up the leg due to a reduced ability of the ankle to damp vibration. Slight differences in posture between subjects and the damping of vibration could result in varying phase lags at the thigh, which could account for the individual differences.

When surface EMG is recorded during WBV, the need to filter motion artifact at the frequency of vibration (21) makes it impossible to determine if the TVR occurs as has been suggested (12, 43). The phase locking of MU firing to the vibration cycle indicates that reflex activation does occur most likely as a result of the TVR. The extent to which this contributes to the overall increase in muscle activity during WBV remains unclear.

There was no overall effect of WBV on the recruitment threshold but increases occurred in low-threshold MUs and decreases in high-threshold ones. It was previously shown that short bouts of local vibration transiently reduce recruitment thresholds (41), while during sustained MVCs it can offset fatigue and subsequently enhance EMG activity particularly in fast-twitch MUs (3). This, coupled with the fact that reduced recruitment thresholds have been observed in higher threshold MUs, supports the suggestion that WBV may preferentially activate fast twitch MUs (36).

The possibility of a preferential activation of fast twitch fibers and the contrasting findings between recruitment thresholds of high- and low-threshold MUs may be explained by different pathways involved in the TVR. H and tendon reflexes are inhibited by locally applied vibration while simultaneously eliciting the TVR (16, 17, 22, 37), an effect attributed to presynaptic inhibition as predominantly monosynaptic reflexes are affected (17, 22, 37). If presynaptic inhibition happened after WBV, then increased recruitment thresholds could occur in fibers innervated via monosynaptic pathways (low threshold) while excitation from polysynaptic pathways could overcome this effect in high-threshold units. Although there was no overall effect on presynaptic inhibition, other presynaptic mechanisms such as homosynaptic postactivation depression, cannot be eliminated.

Much of the theoretical assumption underlying WBV is based on locally applied vibration where a TVR is generated in the vibrated muscle and also reciprocal inhibition in its antagonist (19, 47). During WBV, all muscles are vibrated simultaneously (29) and so vibration of the hamstrings may result in reciprocal inhibition of the VL, thereby increasing recruitment thresholds in low-threshold units while high-threshold units are also likely to be affected by polysynaptic pathways. Locally applied vibration increases activity in some areas of the brain (23, 24) while WBV increases corticospinal pathway excitability (31). This would result in differential effects on low- and high-threshold MUs, although there is no direct evidence for this.

An alternative hypothesis for the reduced recruitment thresholds is changes in MN excitability caused by a postvibratory sensitization of the muscle spindle (41), although reduced spindle sensitivity during and immediately after vibration has been found (34). Involuntary contractions similar to the “Kohnstamm Phenomenon” after muscle/tendon vibration have been attributed to an increased descending supraspinal input rather than changes in muscle spindle resting discharge (33), providing further support that decreases in fast-twitch MU recruitment threshold are due to a polysynaptic component. Currently there is no direct evidence to support one mechanism over the other and they are not mutually exclusive.

An acute bout of WBV has been reported to improve power (11, 14, 42), but its effects on strength are less clear (45, 46). Reduced recruitment thresholds of fast-twitch fibers may be responsible for the improvements observed and could explain the greater effect on power by an increased contractile speed. An increased rate of force development of electrically evoked twitches after WBV indicate that this may be the case (13).

A limitation of the current study is that when MUs were categorized there are relatively few in each category. It would be valuable to study a greater number of MUs, particularly high-threshold ones, but due to the difficulties in identifying single MUs at higher forces this was not possible. MU recruitment thresholds decrease after a MVC or multiple submaximal contractions (44), but as we did not find this in all MUs it appears that the intervals between ramp contractions were sufficient to minimize this.

Inevitably the study has some limitations. If smaller MUs are more sensitive to presynaptic inhibition then testing at 30% Mmax may not be sensitive enough to distinguish between high- and low-threshold MUs. However, this intensity has been used previously (26) and the soleus is thought to have a relatively homogenous fiber type distribution (27). Assessing presynaptic inhibition using a range of relative H-reflex amplitudes could be helpful in distinguishing between MUs of different thresholds. Ideally threshold and presynaptic inhibition would have been examined in the same muscle. The soleus is one of the best muscles for reliable resting measurements of the H-reflex, but these are very difficult to obtain in the quadriceps. Ideally we would have measured single MUs in the soleus but found that they were very difficult to identify during vibration due to motion artifact.

This is the first study to identify single MUs during WBV and their effect on recruitment thresholds. A strong relationship was found between the timing of MU firing and the phase of the WBV cycle, which has been interpreted to confirm the presence of reflex muscle activity during WBV. The recruitment threshold of low-threshold MUs increased after WBV, although this does not appear to be related to changes in presynaptic inhibition. The opposite effect on higher threshold MUs may be due to use of polysynaptic pathways not involved with low-threshold units. This preferential effect on higher threshold MUs may be responsible for the greater effect on power than strength reported after WBV (35).

GRANTS

We are grateful for funding received from Research into Ageing.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.D.P., F.C.M., and D.J.N. conception and design of research; R.D.P. and D.J.N. performed experiments; R.D.P. and R.C.W. analyzed data; R.D.P., R.C.W., and D.J.N. interpreted results of experiments; R.D.P. prepared figures; R.D.P. and D.J.N. drafted manuscript; R.D.P., R.C.W., F.C.M., and D.J.N. edited and revised manuscript; R.D.P., F.C.M., and D.J.N. approved final version of manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tony Christopher and Lindsey Marjoram for their technical assistance and Paul Seed for his assistance with the statistics.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abercromby AFJ, Amonette WE, Layne CS, McFarlin BK, Hinman MR, Paloski WH. Variation in neuromuscular responses during acute whole-body vibration exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 1642–1650, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bianconi R, Van Der Meulen JP. The response to vibration of the end organs of mammalian muscle spindles. J Neurophysiol 26: 177–190, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bongiovanni LG, Hagbarth KE. Tonic vibration reflexes elicited during fatigue from maximal voluntary contractions in man. J Physiol 423: 1–14, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bongiovanni LG, Hagbarth KF, Stjernberg L. Prolonged muscle vibration reducing motor output in maximal voluntary contractions in man. J Physiol 423: 15–26, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bressel E, Smith G, Branscomb J. Transmission of whole body vibration in children while standing. Clin Biomech 25: 181–186, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown MC, Engberg I, Matthews PBC. The relative sensitivity to vibration of muscle receptors of the cat. J Physiol 192: 773–800, 1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Burke D, Hagbarth KE, Lofstedt L, Wallin BG. The responses of human muscle spindle endings to vibration of non-contracting muscles. J Physiol 261: 673–693, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Burke D, Schiller HH. Discharge pattern of single motor units in the tonic vibration reflex of human triceps surae. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 39: 729–741, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Burke JR, Hagbarth KE, Lofstedt L, Wallin BG. Response of human muscle-spindle endings to vibration during isometric contraction. J Physiol 261: 695–711, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cardinale M, Bosco C. The use of vibration as an exercise intervention. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 31: 3–7, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cardinale M, Lim J. The acute effects of two different whole body vibration frequencies on vertical jump performance. Med Sport (Roma) 56: 287–292, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cardinale M, Lim J. Electromyography activity of vastus lateralis muscle during whole-body vibrations of different frequencies. J Strength Cond Res 17: 621–624, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cochrane D, Stannard S, Firth E, Rittweger J. Acute whole-body vibration elicits post-activation potentiation. Eur J Appl Physiol 108: 311–319, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cochrane DJ, Stannard SR. Acute whole body vibration training increases vertical jump and flexibility performance in elite female field hockey players. Br J Sports Med 39: 860–865, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Crone C, Hultborn H, Mazieres L, Morin C, Nielsen J, Pierrot-Deseilligny E. Sensitivity of monosynaptic test reflexes to facilitation and inhibition as a function of the test reflex size: a study in man and the cat. Exp Brain Res 81: 35–45, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Gail P, Lance JW, Neilson PD. Differential effects on tonic and phasic reflex mechanisms produced by vibration of muscles in man. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 29: 1–11, 1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Desmedt JE, Godaux E. Mechanism of the vibration paradox: excitatory and inhibitory effects of tendon vibration on single soleus muscle motor units in man. J Physiol 285: 197–207, 1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Desmedt JE, Godaux E. Vibration-induced discharge patterns of single motor units in the masseter muscle in man. J Physiol 253: 429–442, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Eklund G, Hagbarth KE. Normal variability of the tonic vibration reflexes in man. Exp Neurol 16: 80–92, 1966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fallon JB, Macefield VG. Vibration sensitivity of human muscle spindles and golgi tendon organs. Muscle Nerve 36: 21–29, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fratini A, Cesarelli M, Bifulco P, Romano M. Relevance of motion artifact in electromyography recordings during vibration treatment. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 19: 710–718, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gillies JD, Lance JW, Neilson PD, Tassinari CA. Presynaptic inhibition of the monosynaptic reflex by vibration. J Physiol 205: 329–339, 1969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Golaszewski SM, Siedentopf CM, Baldauf E, Koppelstaetter F, Eisner W, Unterrainer J, Guendisch GM, Mottaghy FM, Felber SR. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of the human sensorimotor cortex using a novel vibrotactile stimulator. NeuroImage 17: 421–430, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Golaszewski SM, Siedentopf CM, Koppelstaetter F, Fend M, Ischebeck A, Gonzalez-Felipe V, Haala I, Struhal W, Mottaghy FM, Gallasch E, Felber SR, Gerstenbrand F. Human brain structures related to plantar vibrotactile stimulation: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. NeuroImage 29: 923–929, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hagbarth KE, Hellsing G, Lofstedt L. TVR and vibration-induced timing of motor impulses in the human jaw elevator muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 39: 719–728, 1976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hayes BT, Hicks-Little CA, Harter RA, Widrick JJ, Hoffman MA. Intersession reliability of Hoffmann reflex gain and presynaptic inhibition in the human soleus muscle. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 90: 2131–2134, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson MA, Polgar J, Weightman D, Appleton D. Data on the distribution of fibre types in thirty-six human muscles. An autopsy study. J Neuro Sci 18: 111–129, 1973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kanda K. Contribution of polysynaptic pathways to the tonic vibration reflex. Jpn J Physiol 22: 367–377, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matthews PB. The relative unimportance of the temporal pattern of the primary afferent input in determining the mean level of motor firing in the tonic vibration reflex. J Physiol 251: 333–361, 1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. McGrath GJ, Matthews PBC. Evidence from the use of vibration during procaine nerve block that the spindle group II fibres contribute excitation to the tonic stretch reflex of the decerebrate cat. J Physiol 235: 371–408, 1973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mileva KN, Bowtell JL, Kossev AR. Effects of low-frequency whole-body vibration on motor-evoked potentials in healthy men. Exp Physiol 94: 103–116, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pollock RD, Woledge RC, Mills KR, Martin FC, Newham DJ. Muscle activity and acceleration during whole body vibration: Effect of frequency and amplitude. Clin Biomech 25: 840–846, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ribot-Ciscar E, Roll JP, Gilhodes JC. Human motor unit activity during post-vibratory and imitative voluntary muscle contractions. Brain Res 716: 84–90, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ribot-Ciscar E, Rossi-Durand C, Roll JP. Muscle spindle activity following muscle tendon vibration in man. Neurosci Lett 258: 147–150, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rittweger J. Vibration as an exercise modality: how it may work, and what its potential might be. Eur J Appl Physiol 108: 877–904, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rittweger J, Beller G, Felsenberg D. Acute physiological effects of exhaustive whole-body vibration exercise in man. Clin Physiol 20: 134–142, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roll JP, Martin B, Gauthier GM, Ivaldi FM. Effects of whole body vibration on spinal reflexes in man. Aviat Space Environ Med 51: 1227–1233, 1980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roll JP, Vedel JP. Kinaesthetic role of muscle afferents in man, studied by tendon vibration and microneurography. Exp Brain Res 47: 177–190, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Roll JP, Vedel JP, Ribot E. Alteration of proprioceptive messages induced by tendon vibration in man: a microneurographic study. Exp Brain Res 76: 213–222, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Romaiguere P, Vedel JP, Azulay JP, Pagni S. Differential activation of motor units in the wrist extensor muscles during the tonic vibration reflex in man. J Physiol 444: 645–667, 1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Romaiguere P, Vedel JP, Pagni S. Effects of tonic vibration reflex on motor unit recruitment in human wrist extensor muscles. Brain Res 602: 32–40, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ronnestad BR. Acute effects of various whole-body vibration frequencies on lower-body power in trained and untrained subjects. J Strength Cond Res 23: 1309–1315, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Seidel H. Myoelectric reactions to ultra-low frequency and low-frequency whole-body vibration. Eur J Appl Physiol 57: 558–562, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suzuki S, Hayami A, Suzuki M, Watanabe S, Hutton RS. Reductions in recruitment force thresholds in human single motor units by successive voluntary contractions. Exp Brain Res 82: 227–230, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Torvinen S, Kannus P, Sievanen H, Jarvinen TAH, Pasanen M, Kontulainen S, Jarvinen TLN, Jarvinen M, Oja P, Vuori I. Effect of a vibration exposure on muscular performance and body balance. Randomized cross-over study. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 22: 145–152, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torvinen S, Sievanen H, Jarvinen TAH, Pasanen M, Kontulainen S, Kannus P. Effect of 4-min vertical whole body vibration on muscle performance and body balance: a randomized cross-over study. Int J Sports Med 23: 374–379, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tyler AE, Hutton RS. Was Sherrington right about co-contractions? Brain Res 370: 171–175, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wakeling JM, Nigg BM, Rozitis AI. Muscle activity damps the soft tissue resonance that occurs in response to pulsed and continuous vibrations. J Appl Physiol 93: 1093–1103, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.