Abstract

Thalamocortical neurons in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) dynamically communicate visual information from the retina to the neocortex, and this process can be modulated via activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs). Neurons within dLGN express different mGluR subtypes associated with distinct afferent synaptic pathways; however, the physiological function of this organization is unclear. We report that the activation of mGluR5, which are located on presynaptic dendrites of local interneurons, increases GABA output that in turn produces an increased inhibitory activity on proximal but not distal dendrites of dLGN thalamocortical neurons. In contrast, mGluR1 activation produces strong membrane depolarization in thalamocortical neurons regardless of distal or proximal dendritic locations. These findings provide physiological evidence that mGluR1 appear to be distributed along the thalamocortical neuron dendrites, whereas mGluR5-dependent action occurs on the proximal dendrites/soma of thalamocortical neurons. The differential distribution and activation of mGluR subtypes on interneurons and thalamocortical neurons may serve to shape excitatory synaptic integration and thereby regulate information gating through the thalamus.

Keywords: dLGN, inhibition, postsynaptic

glutamate activates two broad classes of receptors, ionotropic glutamate receptors and metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), which can be activated by retinogeniculate and corticothalamic pathways in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN; Granseth 2004; Scharfman et al. 1990; Turner and Salt 1998). Multiple mGluR subtypes have been identified, and many of these are differentially localized within the thalamocortical circuit (Conn and Pin 1997). Activation of corticothalamic afferents engage mGluRs producing multiple actions via both pre- and postsynaptic mechanisms (Alexander and Godwin 2005, 2006; Govindaiah and Cox 2006, 2009; McCormick and von Krosigk 1992; Turner and Salt 1999, 2000). Activation of mGluR1 (member of group I mGluRs) either by synaptic activation or selective agonists produces a depolarization of thalamocortical relay neurons (Turner and Salt 2000) and is the likely mechanism that produces a switch in the response mode of thalamocortical relay cells from burst to tonic firing following mGluR1 activation in vivo (Godwin et al. 1996b). In contrast, activation of groups II and III mGluRs attenuates corticothalamic excitation via presynaptic mechanisms (Alexander and Godwin 2005; Turner and Salt 1999).

Local dLGN inhibitory interneurons are unique in that they give rise to two distinct types of output: axonal and dendritic (Famiglietti and Peters 1972; Guillery 1969; Hamos et al. 1985; Montero 1986; Ralston 1971). The conventional axonal output of interneurons forms both axodendritic and axosomatic inhibitory synapses onto thalamocortical neurons and are referred to as F1 terminals. These interneurons also have GABA-containing dendrites that form dendrodendritic synapses onto thalamocortical neurons and are termed F2 terminals. Retinogeniculate axons innervate both F2 terminals and relay neuron dendrite. The F2 terminals in turn synapse nearby onto the same relay neuron dendrite to form a triadic arrangement. Because of the proximity of the F2 terminal to the excitatory retinogeniculate synapse onto the relay neuron, these inhibitory inputs are thought to regulate retinogeniculate transmission focally (Steriade 2004), and these presynaptic dendrites also contain the other member of group I mGluRs, namely mGluR5 (Godwin et al. 1996a). Activation of mGluR5 produces diverse actions on visual responses in dLGN thalamocortical neurons in vivo (de Labra et al. 2005). Furthermore, in vitro studies indicate that mGluR5 activation by agonists or activation of retinogeniculate afferents increases inhibitory activity within thalamocortical neurons via selective activation of F2 terminals (Cox et al. 1998; Cox and Sherman 2000; Govindaiah and Cox 2004, 2006; Lam et al. 2005).

Anatomic studies indicate that retinogeniculate and corticothalamic afferents are differentially distributed on the dendritic arbor of thalamocortical relay neurons and thus may represent distinct functional influences on thalamic gating. Retinogeniculate inputs, and associated triadic arrangements, are preferentially localized on the proximal dendrites (Erişir et al. 1997; Wilson et al. 1984, 1996). In contrast, corticothalamic inputs are preferentially distributed on distal dendrites of thalamocortical neurons (Erişir et al. 1997; Wilson et al. 1984). In addition, group I mGluRs are presumably differentially localized in the dLGN: mGluR5 are localized to dendrites of local interneurons, whereas mGluR1 are localized to thalamocortical neuron dendrites opposite to corticothalamic afferents (Godwin et al. 1996a; Vidnyanszky et al. 1996). Considering the differential localization of mGluRs and their distinct actions in the dLGN, we have investigated the physiological consequences arising from specific mGluR subtypes in dLGN by local activation of these receptors. We found diverse actions of mGluR activation that are heterogeneously distributed along the dendritic axis within thalamocortical neurons. Activation of F2 terminals by mGluR5 activation was primarily restricted to proximal dendrites, whereas the postsynaptic depolarizing actions of mGluR activation via mGluR1 was present at both proximal and distal dendritic sites. Depending on how synaptic activation of glutamatergic inputs engage these different receptors, such diverse mGluR-mediated actions could play a critical role in integrating cortical and sensory inputs onto thalamocortical neurons.

METHODS

All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the University of Illinois Animal Care and Use Committee. Care was taken to minimize the number of animals used to complete this series of experiments, and animals were deeply anesthetized to prevent any possible suffering.

Brain slice preparation.

Thalamic slices were prepared from Sprague-Dawley rats (postnatal age: 14–21 days) as previously described (Govindaiah and Cox 2004, 2006). Briefly, animals were deeply anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg ip) and decapitated, and brains were placed into cold (4°C), oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) slicing solution containing (in mM): 2.5 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 234 sucrose, and 11 glucose. Parasagittal or coronal slices (250- to 300-μm thickness) were cut at the level of dLGN using a vibrating tissue slicer (Govindaiah and Cox 2004; Turner and Salt 1998). Slices were incubated in oxygenated (95% O2-5% CO2) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing, in mM, 126 NaCl, 26 NaHCO3, 2.5 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, and 10 glucose at 32°C for ≥60 min before recording. The recording chamber was maintained at 32°C, and slices were continuously superfused with ACSF (3.0 ml/min).

Recording procedures.

Whole cell recordings were obtained from dLGN neurons as described previously (Govindaiah and Cox 2006). Recording pipettes were pulled from borosilicate glass capillaries with tip resistances of 3–5 MΩ. For current-clamp experiments, pipettes were filled with a solution containing (in mM): 117 K-gluconate, 13 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.07 CaCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na-ATP, and 0.4 Na-GTP. In some voltage-clamp experiments, electrodes were filled with a cesium-based solution containing (in mM): 117 Cs-gluconate, 13 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.07 CaCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Na2-ATP, and 0.4 Na-GTP. The pH and osmolality of internal solution were adjusted to 7.3 and 290 mosmol/kgH2O, respectively. A subset of neurons were filled with a fluorescent dye (Alexa Fluor 594; 50 μM) that was added to the pipette solution to identify the morphology of the recorded neurons. Miniature inhibitory synaptic currents (mIPSCs) were recorded in the presence of TTX (1 μM) with a 0-mV holding potential to optimize the mIPSC recordings. Signals were obtained using a MultiClamp 700A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA), low-pass filtered at 2.5 kHz, digitized at 10 kHz, and stored on a computer for offline analyses (pCLAMP; Molecular Devices).

Application of pharmacological agents.

Concentrated stock solutions of pharmacological agents were prepared, stored as recommended, and diluted in ACSF to a final concentration before use. For bath application, agonists were applied via a short bolus into the input line of the recording chamber using a syringe pump (Govindaiah and Cox 2006). All antagonists were bath-applied at least 5–10 min before agonist application. All compounds were purchased from Tocris (Ellisville, MO) or Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Focal application of the mGluR agonist (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG; 50 μM) was accomplished using pressure ejection via a glass pipette (2–3 psi, 10–25 ms). To estimate the spatial spread of pressure ejection, a fluorescent indicator (Alexa Fluor 594; 50 μM) was also included in glass pipettes containing DHPG in subsets of neurons as described previously (Crandall et al. 2010). The ejection pressure (2–3 psi) was optimized based on spatial spread of the dye. The radial spread of the dye was estimated <20 μm for a given location.

Histology.

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described earlier with minor modifications (Venkitaramani et al. 2009). Briefly, rats (postnatal age 17–21 days) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in 0.1 M PBS. The brains were postfixed in 4% PFA overnight and cryoprotected in 10, 20, and 30% sucrose in PBS in succession. The cryopreserved brain tissue was sectioned along the horizontal plane at 40-μm thickness and stored in cryoprotective buffer at −20°C until processed for immunohistochemistry. Tissue sections were washed with PBS, permeabilized in PBS containing 0.2% Triton X-100 (PBS-T), and then blocked with 10% normal donkey serum (NDS) + 3% BSA in PBS-T for 1 h. The sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies [glutamic acid decarboxylases GAD65/67 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), 1:300; GAD6 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), 1:400; mGluR5 (Abcam), 1:500] diluted in 1% NDS + 1% BSA in PBS-T. The sections were washed and incubated with secondary antibodies from Invitrogen (donkey anti-goat Alexa Fluor 647, donkey anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 555, and donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488, 1:400) at room temperature for 2 h. The sections were washed extensively with 1× PBS-T and mounted onto precleaned/coated slides. The slides were coverslipped using ProLong Gold antifade, allowed to cure, and sealed with nail polish. Immunofluorescence was visualized on a Leica laser scanning confocal microscope.

Data analyses.

IPSCs were detected and analyzed using Mini Analysis Program software (Synaptosoft, Leonia, NJ). The threshold for IPSC detection was 10 pA, and automatic detection was verified post hoc by visual analysis (Govindaiah and Cox 2006). Our detection criteria were also tested on recordings in the presence of the GABAA receptor antagonist SR-95531 (10 μM) to verify that false-positive responses were not being detected. For quantification of mIPSCs, mIPSC frequency was binned in 1-s increments. The average mIPSC frequency was calculated from 5-s windows before and following DHPG application. Population data are expressed as means ± SE, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

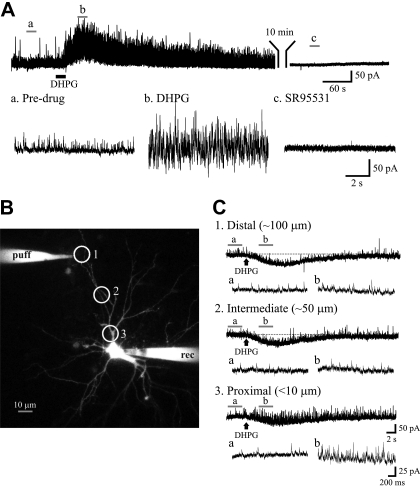

Bath application of the selective group I mGluR agonist DHPG (25 μM, 15 s) produces a robust, long-lasting increase in mIPSC activity in thalamocortical relay neurons (Fig. 1A). The mIPSCs were completely attenuated by the GABAA receptor antagonist SR-95531 (10 μM; Fig. 1A). This increased mIPSC activity persisted in the presence of the sodium channel blocker TTX in a subset of neurons (6 of 9). In the remaining 3 neurons, DHPG did not alter mIPSC activity in TTX. These results indicate that the DHPG-mediated effects were similar to that observed in cat dLGN, producing TTX-sensitive increases in spontaneous IPSCs in a subpopulation of thalamic relay neurons (Cox et al. 1998; Cox and Sherman 2000). The TTX-insensitive increase in inhibition is attributable to activation of mGluR5 on presynaptic dendrites of interneurons (F2 terminals), whereas the TTX-sensitive increase in inhibition is attributable to activation of axonal output (F1 terminals) via suprathreshold excitation of thalamic reticular nucleus neurons and/or local interneurons (Cox et al. 1998; Cox and Sherman 2000; Govindaiah and Cox 2004, 2006). In this study, we will refer to F2-positive and F2-negative responses, which signify TTX-insensitive and TTX-sensitive responses from our previous work.

Fig. 1.

Proximal but not distal (RS)-3,5-dihydroxyphenylglycine (DHPG) application increases miniature inhibitory synaptic current (mIPSC) frequency in dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) thalamocortical neurons. A: current trace showing mIPSCs recorded from a thalamocortical neuron at holding potential of 0 mV in the presence of TTX (1 μM). The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR1) agonist DHPG (25 μM) increases the frequency of mIPSCs (“b”) relative to baseline levels (“a”). The spontaneous IPSC activity is completely attenuated by GABAA in receptor antagonist SR-95531 (“c,” 10 μM). B: typical thalamocortical neuron loaded with Alexa Fluor 594 (50 μM) to perform focal DHPG application under visual guidance. Whole cell recordings were obtained from the soma (rec), whereas DHPG was focally applied at different locations surrounding the neuron as indicated by circles. C: representative current traces obtained from a dLGN thalamocortical neuron in the presence of TTX (1 μM) to show the effects of focal DHPG application at different locations. At distal site (100 μm), DHPG produces only an inward current. At more proximal sites, 50 and <10 μm, DHPG application produces a robust increase in the mIPSC frequency (“b”) compared with baseline activity (“a”) in addition to the inward current. Representative current traces before (“a”) and following DHPG application (“b”) are shown in expanded time scale at the bottom. The expanded traces at the bottom correspond to the underlined region in the top traces.

Despite anatomic studies indicating that retinogeniculate innervation and accompanying triadic arrangements containing F2 terminals are preferentially located on proximal dendrites of thalamocortical neurons (Wilson et al. 1984), the physiological evidence of such arrangement is absent. To test this hypothesis, we focally applied DHPG (50 μM) using low-pressure ejection (2 psi, 10-ms pulses) under visual guidance at different distances from the thalamocortical neuron soma in the presence of TTX (Fig. 1B). The application of DHPG on proximal dendrites (<10 μm from soma) produced a robust increase in mIPSC activity, but such increases were not observed on distal dendrites (∼100 μm from soma; Fig. 1, B and C). The increase in mIPSC frequency by proximal but not distal DHPG application was observed in 10 of 16 thalamocortical neurons (Fig. 2A). Despite the lack of mIPSC activity change to distal DHPG application, a slow inward current via direct postsynaptic action of DHPG on the thalamocortical neuron was present indicating the agonist was being detected by the neuron. In the remaining 6 neurons, DHPG did not alter the mIPSC activity when applied at either proximal or distal locations, but the slow inward current was still present (Fig. 2B). The presence of 2 neuronal populations, F2-positive and F2-negative, is expected considering F2 innervation of thalamocortical neurons occurs in a subpopulation of thalamocortical neurons.

Fig. 2.

Lack of DHPG-mediated increases in mIPSC activity in subsets of dLGN thalamocortical neurons. Ai: current recording from dLGN thalamocortical neuron in presence of TTX (1 μM) reveals strong increase in mIPSC activity following DHPG (100 μM) application at proximal and intermediate sites (F2-positive). DHPG application to distal region did not alter mIPSC activity. Aii: graph illustrates the time course of the DHPG-mediated alterations in mIPSC frequency at different locations. The frequency of mIPSCs were binned for 1 s and shown for 5 s before and 25 s following DHPG application. Bi: representative current traces obtained from a dLGN thalamocortical neuron in presence of TTX (1 μM) reveals no alterations in mIPSC activity following DHPG (100 μM) application (F2-negative). However, DHPG produce inward currents in this neuron. Bii: plot revealing time course of mIPSC frequency over time starting 5 s before and 25 s following DHPG application. The data are plotted as means ± SE.

Within F2-positive neurons, the increase in mIPSC frequency produced by DHPG was dependent on the location along the dendritic arbor (Fig. 2Aii). DHPG application at the proximal dendrite (<10 and 25 μm from soma) resulted in robust, significant increase in mIPSC frequency (<10 μm: pre-DHPG: 7.9 ± 0.7 Hz, DHPG: 22.1 ± 1.5 Hz, P < 0.001, n = 10, paired t-test; 25 μm: pre-DHPG: 7.3 ± 1.5 Hz, DHPG: 17.0 ± 2.5 Hz, P < 0.01, n = 6). At intermediate distances (∼50 μm), DHPG produced a significant but smaller magnitude increase in mIPSC frequency (pre-DHPG: 6.1 ± 1.2 Hz, DHPG: 8.7 ± 1.9 Hz, n = 7, P = 0.04, paired t-test). DHPG application of DHPG to distal dendrites (∼100 μm away from the soma) did not significantly increase mIPSC frequency (pre-DHPG: 6.7 ± 1.1 Hz, DHPG: 9.0 ± 1.9 Hz, n = 7; P > 0.05, paired t-test). In the overall population, the peak effect of DHPG on mIPSC activity reveals a significant difference in the magnitude of effects comparing proximal dendrite to distal dendrite application (F = 12.4, P < 0.001, n = 10, 1-way ANOVA).

In the F2-negative neurons (n = 6), DHPG did not significantly alter mIPSC activity at proximal or distal locations (Fig. 2Bii). DHPG application to proximal dendrite (<10 μm) resulted in a small, insignificant increase in mIPSC activity from 6.3 ± 1.2 to 7.2 ± 1.3 Hz (n = 6; P > 0.05, paired t-test). Similarly, DHPG application at distal sites (100 μm) did not significantly alter mIPSC activity (control: 7.1 ± 1.8 Hz, DHPG: 7.9 ± 2.1 Hz, n = 6, P > 0.05, paired t-test).

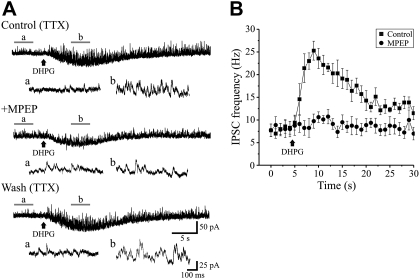

Considering our previous results indicate that increased inhibition by DHPG is mediated specifically by mGluR5, we tested whether the focal activation by DHPG on IPSCs is significantly altered by the selective mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP). In control conditions, DHPG (50 μM) application to proximal dendrites significantly increased the mIPSC frequency from 8.2 ± 1.2 to 23.1 ± 1.9 Hz (Fig. 3; n = 7; P < 0.0001, paired t-test). In the presence of MPEP (50–75 μM), subsequent DHPG application produced a minimal increase in IPSC frequency (MPEP: 7.9 ± 1.4 Hz, MPEP+DHPG: 9.9 ± 1.4 Hz, n = 7) confirming the role of mGluR5.

Fig. 3.

Proximal activation of mGluR5 increases mIPSCs in dLGN neurons. A: DHPG (100 μM) application to proximal dendrites increases mIPSC frequency (“b”) relative to baseline (“a”). The increase in mIPSC frequency by DHPG is attenuated by the mGluR5 antagonist 2-methyl-6-(phenylethynyl)pyridine hydrochloride (MPEP; 50 μM) in a reversible manner. The expanded traces at the bottom correspond to the underlined region in the top traces. B: the graph illustrates the time course of the DHPG-mediated alterations in mIPSC frequency. Individual bar represents the number of events in consecutive 1-s bins for 5 s before and 25 s following DHPG application. Values are plotted as means ± SE.

Colocalization of mGluR5 and GAD.

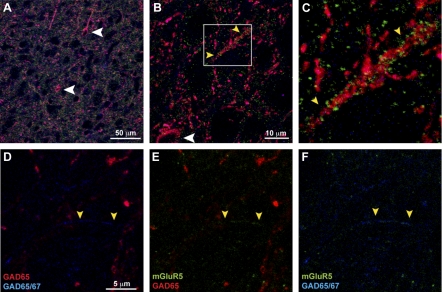

Considering previous studies demonstrating the localization of mGluR5 to dendrites of local GABAergic interneurons were carried out in cat dLGN (Godwin et al. 1996a), we determined whether such colocalization occurs within the rat dLGN even though our previous pharmacological data suggest such a distribution (Govindaiah and Cox 2004, 2006). To determine the expression profile of mGluR5 and GABAergic terminals in dLGN, we performed triple labeling with mGluR5, GAD65, and GAD65/67. The GABAergic interneurons in the dLGN were immunostained by both GAD65 (red) and GAD65/67 (blue) antibody (Fig. 4A). The GABA-containing cell bodies are indicated by white arrowheads (Fig. 4, A and B). The GAD65 immunoreactivity completely colocalized with GAD65/67, as indicated by magenta color (Fig. 4, A–C). However, we observed regions that were only labeled with GAD65/67 antibody but not GAD65 antibody (blue staining), representing GAD67-specific immunoreactivity (Fig. 4, D–F). This is consistent with previously described differences in GAD65 and GAD67 staining (Esclapez et al. 1994). The mGluR5 (green) immunofluorescence extensively colocalized with both GAD65 and GAD65/67 staining (Fig. 4, A–C). We did not detect mGluR5 immunolabeling in areas devoid of GAD65/67 staining. Interestingly, we also detected mGluR5 immunofluorescence in processes (indicated by yellow arrowheads) that were exclusively labeled by GAD67 alone (Fig. 4, D–F). Thus immunohistochemistry supports the electrophysiology data that mGluR5 is preferentially distributed in presynaptic terminals of GABAergic interneurons.

Fig. 4.

Expression of mGluR5 and glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) in rat dLGN. A and B: colocalization of mGluR5 (green) with GAD65 (red) and GAD65/67 (blue) in cell bodies (white arrowheads) and processes (yellow arrowheads) of GABAergic interneurons. C: higher magnification of region in B illustrating colocalization of mGluR5 in a GAD-containing process. D–F: higher magnification of a representative region showing processes (yellow arrowheads) labeled with GAD67 alone that colocalize with mGluR5 immunoreactivity.

Postsynaptic actions of mGluR1 in thalamocortical neurons.

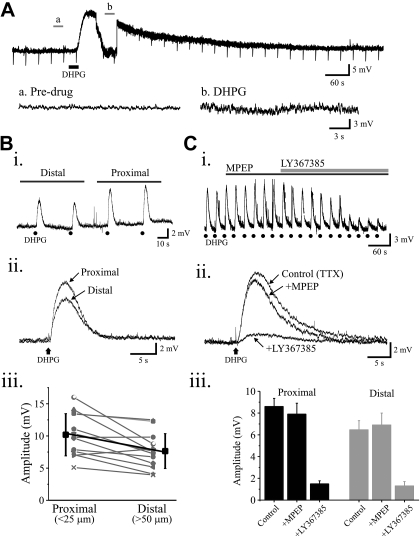

Anatomic studies indicate that mGluR1 are localized to thalamocortical neuron dendrites (Godwin et al. 1996a; Vidnyanszky et al. 1996), and the activation of mGluR1 has been associated with corticothalamic but not retinogeniculate innervation. Considering corticothalamic innervation may be preferentially distributed to distal dendrites of thalamocortical neurons (Erişir et al. 1997), we tested whether the postsynaptic depolarizing actions of mGluRs may be spatially distributed. Bath application of DHPG (25 μM) in the presence of TTX (1 μM) results in a long-lasting membrane depolarization (Fig. 5A; 11.2 ± 3.4 mV, n = 9), but the source of such actions is unclear. Using focal DHPG application in the presence of TTX, DHPG (50 μM) elicited stable membrane depolarizations when applied at 30-s intervals (Fig. 5B, i and ii). DHPG elicited average membrane depolarizations of 7.6 ± 0.7 mV (n = 14) and 10.1 ± 0.8 mV (n = 14) when focally applied to distal (50–100 μm) and proximal (0–25 μm) dendrites, respectively (Fig. 5Biii). The amplitudes of the depolarizations at these different locations were statistically significant with larger responses evoked by proximal application (P < 0.001, n = 14, paired t-test). As illustrated in Fig. 5C, the selective mGluR5 antagonist MPEP (50–75 μM) did not significantly alter the membrane depolarizations elicited by DHPG application to proximal dendrites (DHPG: 8.6 ± 0.7 mV, MPEP+DHPG: 7.9 ± 1.0 mV, n = 14; P > 0.9, paired t-test) or to distal dendrites (DHPG: 7.6 ± 0.9 mV, MPEP+DHPG: 6.9 ± 0.8 mV, n = 5; P > 0.8, paired t-test). In contrast, the selective mGluR1 antagonist LY 367385 (100 μM) strongly attenuated the DHPG-mediated depolarization (Fig. 5C). The depolarization produced by focal DHPG application onto proximal dendrites (DHPG: 8.6 ± 1.4 mV, LY 367385+DHPG: 1.5 ± 0.3 mV, n = 13; P < 0.0001, paired t-test) or distal dendrites (DHPG: 7.3 ± 1.0 mV, LY 367385+DHPG: 1.3 ± 0.4 mV, n = 6; P < 0.0002, paired t-test) were significantly attenuated by LY 367385, indicating the role of mGluR1 on the postsynaptic depolarization of thalamocortical neurons.

Fig. 5.

Activation of postsynaptic mGluR1 but not mGluR5 elicits membrane depolarization in dLGN thalamocortical neurons. A: representative voltage trace from a dLGN neuron revealing that DHPG produces a robust depolarization. Traces are shown in expanded time scale before (“a”) and following exposure to DHPG (“b”). Downward deflections are the hyperpolarizing current pulses (20 pA, 50 ms) to monitor changes in input resistance. Bi: voltage traces from a representative thalamocortical neuron reveals that focal DHPG (50 μM) application to either proximal or distal sites elicits membrane depolarization. DHPG application is indicated by black dots (●). Bii: overlapping of DHPG-mediated responses to proximal and distal sites reveals that the responses to proximal sites is larger than to distal sites. Biii: scatterplot illustrating the amplitude of the DHPG-mediated depolarizations in response to proximal and distal application. Ci: in a different thalamocortical neuron, focal DHPG (50 μM) application elicited consistent membrane depolarization when applied at 30-s intervals. The membrane depolarization is not significantly altered following bath application of MPEP (50 μM); however, the selective mGluR1 antagonist LY 367385 (100 μM) attenuates the DHPG-mediated depolarization. DHPG application is indicated by black dots (●). Cii: average traces for each condition are shown. Ciii: population data revealing that LY 367385 but not MPEP significantly reduces (P < 0.0004, paired t-test) amplitude of membrane depolarization elicited by both proximal and distal DHPG application.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides novel physiological evidence that mGluR5 and mGluR1 exert distinct effects in a spatially distributed manner. mGluR5 are localized to dendrites of GABAergic interneurons that synapse onto proximal dendrites of thalamocortical neurons, and activation of these receptors leads to long-lasting inhibition in the thalamocortical neurons. In contrast, mGluR1 is localized to dendrites of thalamocortical neurons, and the activation of these receptors results in long-lasting membrane depolarization. The differential localization of these mGluR subtypes, association with different neuronal types and distinct actions within the dLGN circuitry, could significantly influence the throughput of retinogeniculate transmission to the primary visual cortex.

The actions of mGluR5 and mGluR1 in dLGN.

Multiple mGluR-dependent actions have been described in dLGN in both in vivo and in vitro preparations, which include both inhibitory and excitatory actions mediated by presynaptic and/or postsynaptic mechanisms (Alexander and Godwin 2005, 2006; Cox et al. 1998; Cox and Sherman 2000; Godwin et al. 1996b; Govindaiah and Cox 2006; McCormick and von Krosigk 1992; Rivadulla et al. 2002; Turner and Salt 1999, 2000; Zheng et al. 2008). We have previously demonstrated that activation of mGluR5 by agonists or high-frequency synaptic stimulation of retinogeniculate axons leads to long-lasting inhibition in thalamocortical neurons by enhancing GABA release from presynaptic dendrites of interneurons (F2 synapses; Cox et al. 1998; Cox and Sherman 2000; Govindaiah and Cox 2004, 2006). Activation of these F2 terminals occurs independent of action potential discharge in interneurons and is activity-dependent and thought to influence strongly the retinogeniculate synapse, considering the close proximity of F2 terminals to retinogeniculate synapses onto the dendrite of the thalamocortical neuron, which typically forms triadic arrangements. In the present study, we examined the spatial distribution of these F2 synapses along the thalamocortical/relay neuron by focal activation of mGluRs. We found that mGluR5-dependent activation of F2 synapses occurs on proximal dendritic sites but not at distal dendritic sites. These findings are consistent with the anatomic localization of retinogeniculate inputs and associated triadic arrangements that are preferentially found on proximal dendrites of dLGN thalamocortical neurons.

Second, we found that focal activation of mGluR1 resulted in slow membrane depolarizations in the dLGN relay neuron. Previously, it has been found that mGluR1 receptors are localized with corticothalamic innervation, which typically is found on distal dendrites of relay neurons (Erişir et al. 1997; Godwin et al. 1996a). One would predict that mGluR activation would thus produce depolarizing actions on distal dendrites, which it did; however, we also found strong depolarizations with DHPG application to proximal dendrites indicating that mGluR1 receptors are also near the soma. It is unknown whether these proximal receptors are innervated by corticothalamic inputs or other excitatory synaptic afferents, although it is unlikely to be retinogeniculate inputs because optic tract stimulation cannot evoke an mGluR1-dependent depolarization in relay neurons (Govindaiah and Cox 2004; McCormick and von Krosigk 1992).

Physiological significance.

In the visual pathway, dLGN transfers visual information from retina to the primary visual cortex in a dynamic manner (Guillery and Sherman 2002; Sherman 2001, 2005; Sherman and Guillery 2002). At this level, the relay of visual information is regulated by a complex network of synaptic connections, including complex GABAergic innervation from local interneurons (Guillery and Sherman 2002; Sherman 2005; Sherman and Guillery 2002). The GABAergic circuitry within the dLGN has been shown to contribute significantly to the integration of ascending sensory signals, altering the time course of sensory responses and the tuning of sensory-receptive field properties (Sillito and Kemp 1983; Wang et al. 2011; Zhu and Lo 1998). In addition, inhibitory processes also play a crucial role in the regulation of intrathalamic oscillations associated with sleep/wake states (Guido and Weyand 1995; Steriade et al. 1993; von Krosigk et al. 1993). The present study tested the hypothesis that pre- and postsynaptic mGluR subtypes display diverse distribution and may have distinct functional roles in the visual thalamus. We demonstrate that DHPG application to proximal but not distal dendrites produces long-lasting GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition in thalamocortical neurons. Our physiological evidence is supported by anatomic evidence suggesting the presence of triads formed between retinal axon, interneuron dendrites, and thalamocortical dendrites on proximal dendrites of thalamocortical neurons (Hamos et al. 1985; Wilson 1989). The proximity of the F2 terminals with retinogeniculate afferents position this mGluR5-mediated increase in inhibition to regulate/modulate the magnitude of excitations via the retinogeniculate pathway.

In contrast, activation of mGluR1 produces a postsynaptic depolarization along the dendritic axis. Previous studies indicate that activation of corticothalamic, but not retinogeniculate, afferents can produce an mGluR-dependent depolarization in relay neurons. Anatomic evidence suggests that corticothalamic inputs are preferentially distributed on distal dendrites (Erişir et al. 1997; Wilson et al. 1984), which may lead to smaller influences on somatic activity of relay neurons; however, our findings suggest the presence of mGluR1 mediated depolarization of proximal dendrites as well. Although it appears a bit puzzling that mGluR activation would produce apparent opposing actions on proximal dendrites, it will be important for future studies to delineate whether these opposing actions are actually mediated by either different afferent synaptic pathways or perhaps different activation patterns. Previous in vivo studies suggest that the mGluR1-mediated increase in excitation may serve to modulate the firing mode of these thalamic neurons (Godwin et al. 1996b) and thereby alter thalamocortical throughput in a state-dependent manner.

GRANTS

This research was supported by National Eye Institute Grant EY-014024.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

G.G. and C.L.C. conception and design of research; G.G., D.V., and S.C. performed experiments; G.G., D.V., and S.C. analyzed data; G.G., D.V., and C.L.C. interpreted results of experiments; G.G., D.V., and C.L.C. prepared figures; G.G. drafted manuscript; G.G., D.V., and C.L.C. edited and revised manuscript; G.G., D.V., S.C., and C.L.C. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Alexander GM, Godwin DW. Presynaptic inhibition of corticothalamic feedback by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurophysiol 94: 163–175, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander GM, Godwin DW. Unique presynaptic and postsynaptic roles of Group II metabotropic glutamate receptors in the modulation of thalamic network activity. Neuroscience 141: 501–513, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conn PJ, Pin JP. Pharmacology and functions of metabotropic glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37: 205–237, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Sherman SM. Control of dendritic outputs of inhibitory interneurons in the lateral geniculate nucleus. Neuron 27: 597–610, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox CL, Zhou Q, Sherman SM. Glutamate locally activates dendritic outputs of thalamic interneurons. Nature 394: 478–482, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall SR, Govindaiah G, Cox CL. Low-threshold Ca2+ current amplifies distal dendritic signaling in thalamic reticular neurons. J Neurosci 30: 15419–15429, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Labra C, Rivadulla C, Cudeiro J. Modulatory effects mediated by metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 on lateral geniculate nucleus relay cells. Eur J Neurosci 21: 403–410, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erişir A, Van Horn SC, Bickford ME, Sherman SM. Immunocytochemistry and distribution of parabrachial terminals in the lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat: a comparison with corticogeniculate terminals. J Comp Neurol 377: 535–549, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esclapez M, Tillakaratne NJ, Kaufman DL, Tobin AJ, Houser CR. Comparative localization of two forms of glutamic acid decarboxylase and their mRNAs in rat brain supports the concept of functional differences between the forms. J Neurosci 14: 1834–1855, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV, Jr, Peters A. The synaptic glomerulus and the intrinsic neuron in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. J Comp Neurol 144: 285–334, 1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin DW, Van Horn SC, Erisir A, Sesma M, Romano C, Sherman SM. Ultrastructural localization suggests that retinal and cortical inputs access different metabotropic glutamate receptors in the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci 16: 8181–8192, 1996a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin DW, Vaughan JW, Sherman SM. Metabotropic glutamate receptors switch visual response mode of lateral geniculate nucleus cells from burst to tonic. J Neurophysiol 76: 1800–1816, 1996b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaiah G, Cox CL. Distinct roles of metabotropic glutamate receptor activation on inhibitory signaling in the ventral lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurophysiol 101: 1761–1773, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaiah G, Cox CL. Metabotropic glutamate receptors differentially regulate GABAergic inhibition in thalamus. J Neurosci 26: 13443–13453, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindaiah G, Cox CL. Synaptic activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors regulates dendritic outputs of thalamic interneurons. Neuron 41: 611–623, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granseth B. Dynamic properties of corticogeniculate excitatory transmission in the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in vitro. J Physiol 556: 135–146, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guido W, Weyand T. Burst responses in thalamic relay cells of the awake behaving cat. J Neurophysiol 74: 1782–1786, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW. The organization of synaptic interconnections in the laminae of the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Z Zellforsch Mikrosk Anat 96: 1–38, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillery RW, Sherman SM. Thalamic relay functions and their role in corticocortical communication: generalizations from the visual system. Neuron 33: 163–175, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamos JE, Van Horn SC, Raczkowski D, Uhlrich DJ, Sherman SM. Synaptic connectivity of a local circuit neurone in lateral geniculate nucleus of the cat. Nature 317: 618–621, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam YW, Cox CL, Varela C, Sherman SM. Morphological correlates of triadic circuitry in the lateral geniculate nucleus of cats and rats. J Neurophysiol 93: 748–757, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick DA, von Krosigk M. Corticothalamic activation modulates thalamic firing through glutamate “metabotropic” receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 2774–2778, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero VM. Localization of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in type 3 cells and demonstration of their source to F2 terminals in the cat lateral geniculate nucleus: a Golgi-electron-microscopic GABA-immunocytochemical study. J Comp Neurol 254: 228–245, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston HJ., 3rd Evidence for presynaptic dendrites and a proposal for their mechanism of action. Nature 230: 585–587, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivadulla C, Martinez LM, Varela C, Cudeiro J. Completing the corticofugal loop: a visual role for the corticogeniculate type 1 metabotropic glutamate receptor. J Neurosci 22: 2956–2962, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Lu SM, Guido W, Adams PR, Sherman SM. N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors contribute to excitatory postsynaptic potentials of cat lateral geniculate neurons recorded in thalamic slices. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 4548–4552, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM. Thalamic relay functions. Prog Brain Res 134: 51–69, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM. Thalamic relays and cortical functioning. Prog Brain Res 149: 107–126, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SM, Guillery RW. The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 357: 1695–1708, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sillito AM, Kemp JA. The influence of GABAergic inhibitory processes on the receptive field structure of X and Y cells in cat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN). Brain Res 277: 63–77, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M. Local gating of information processing through the thalamus. Neuron 41: 493–494, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steriade M, McCormick DA, Sejnowski TJ. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science 262: 679–685, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Salt TE. Characterization of sensory and corticothalamic excitatory inputs to rat thalamocortical neurones in vitro. J Physiol 510: 829–843, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Salt TE. Group III metabotropic glutamate receptors control corticothalamic synaptic transmission in the rat thalamus in vitro. J Physiol 519: 481–491, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JP, Salt TE. Synaptic activation of the group I metabotropic glutamate receptor mGlu1 on the thalamocortical neurons of the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus in vitro. Neuroscience 100: 493–505, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkitaramani DV, Paul S, Zhang Y, Kurup P, Ding L, Tressler L, Allen M, Sacca R, Picciotto MR, Lombroso PJ. Knockout of striatal enriched protein tyrosine phosphatase in mice results in increased ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Synapse 63: 69–81, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidnyanszky Z, Gorcs TJ, Negyessy L, Borostyankoi Z, Kuhn R, Knopfel T, Hamori J. Immunocytochemical visualization of the mGluR1a metabotropic glutamate receptor at synapses of corticothalamic terminals originating from area 17 of the rat. Eur J Neurosci 8: 1061–1071, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Krosigk M, Bal T, McCormick DA. Cellular mechanisms of a synchronized oscillation in the thalamus. Science 261: 361–364, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Vaingankar V, Sanchez CS, Sommer FT, Hirsch JA. Thalamic interneurons and relay cells use complementary synaptic mechanisms for visual processing. Nat Neurosci 14: 224–231, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR. Synaptic organization of individual neurons in the macaque lateral geniculate nucleus. J Neurosci 9: 2931–2953, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Forestner DM, Cramer RP. Quantitative analyses of synaptic contacts of interneurons in the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus of the squirrel monkey. Vis Neurosci 13: 1129–1142, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JR, Friedlander MJ, Sherman SM. Fine structural morphology of identified X- and Y-cells in the cat's lateral geniculate nucleus. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 221: 411–436, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Wu X, Li L. Metabotropic glutamate receptors subtype 5 are necessary for the enhancement of auditory evoked potentials in the lateral nucleus of the amygdala by tetanic stimulation of the auditory thalamus. Neuroscience 152: 254–264, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JJ, Lo FS. Control of recurrent inhibition of the lateral posterior-pulvinar complex by afferents from the deep layers of the superior colliculus of the rabbit. J Neurophysiol 80: 1122–1131, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]