Abstract

The adhesion of infected red blood cells (IRBCs) to microvascular endothelium is critical in the pathogenesis of severe malaria. Here we used atomic force and confocal microscopy to examine the adhesive forces between IRBCs and human dermal microvascular endothelial cells. Initial contact of the cells generated a mean ± sd adhesion force of 167 ± 208 pN from the formation of single or multiple bonds with CD36. The strength of adhesion increased by 5- to 6-fold within minutes of contact through a signaling pathway initiated by CD36 ligation by live IRBCs, or polystyrene beads coated with anti-CD36 or PpMC-179, a recombinant peptide representing the minimal binding domain of the parasite ligand PfEMP1 to CD36. Engagement of CD36 led to localized phosphorylation of Src family kinases and the adaptor protein p130CAS, resulting in actin recruitment and CD36 clustering by 50–60% of adherent beads. Uninfected red blood cells or IgG-coated beads had no effect. Inhibition of the increase in adhesive strength by the Src family kinase inhibitor PP1 or gene silencing of p130CAS decreased adhesion by 39 ± 12 and 48 ± 20%, respectively, at 10 dyn/cm2 in a flow chamber assay. Modulation of adhesive strength at PfEMP1-CD36-actin cytoskeleton synapses could be a novel target for antiadhesive therapy.—Davis, S. P., Amrein, M., Gillrie, M. R., Lee, K., Muruve, D. A., Ho, M. Plasmodium falciparum-induced CD36 clustering rapidly strengthens cytoadherence via p130CAS-mediated actin cytoskeletal rearrangement.

Keywords: adhesion, endothelium, malaria, pathogenesis

The distinguishing feature between Plasmodium falciparum and other human malarial infections is the intense sequestration of infected red blood cells (IRBCs) containing mature stages of the parasite in the microcirculation, particularly in the brain (1). Sequestration results from the adhesion, or cytoadherence, of IRBCs to vascular endothelial cells that is mediated by the parasite ligand P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) and endothelial receptors, of which CD36 and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) are the most extensively studied (2). Evidence for cytoadherence as a major pathological process comes not only from detailed histopathological studies of human postmortem tissues (3–5), but also from imaging the microcirculation in infected patients (6) and clinical studies showing decreased cerebral perfusion and lactate production in patients with severe falciparum malaria (7, 8). The importance of cytoadherence is further supported by the increased prevalence of protective point mutations in the hemoglobin gene within human populations living in malaria-endemic areas. Specifically, individuals with hemoglobin C disease (9) or heterozygous for hemoglobin S (10) are protected from the complications of severe falciparum malaria due in part to an abnormal display of PfEMP1 on the surface of IRBCs, which profoundly affects their ability to adhere to the endothelial cell. These observations clearly indicate that reducing cytoadherence is a therapeutic option for improving clinical outcome.

We have previously reported that the number of adherent cells in a flow chamber assay that measures IRBC adhesion in bulk flow could be increased by a change in the phosphorylation status of Thr92 in the ectodomain of CD36 (11, 12). This amino acid is constitutively phosphorylated in endothelial CD36, but may become dephosphorylated on receptor activation by GPI-anchored alkaline phosphatase in a Src family kinase-dependent process, analogous to the dephosphorylation of platelet CD36 by acid phosphatases that are released on binding of the natural ligand thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1; ref. 13). Dephosphorylation of the ectodomain of CD36 resulted in increased binding of TSP-1 and IRBCs. Our experimental results were subsequently validated in a phase II clinical trial of levamisole, a specific alkaline phosphatase inhibitor, in patients with uncomplicated falciparum malaria (14). A 5-fold increase in the number of mature stages of the parasite was seen in the peripheral blood of patients who received quinine sulfate plus a single dose of levamisole compared to quinine sulfate alone. In other words, IRBCs that would normally have adhered and sequestered were remaining in the circulation, where they could be cleared by the spleen. More important, the persistence of a higher trophozoite/schizont parasitemia did not result in worsening of the clinical manifestations.

Bulk flow assays used in the above studies provide a convenient means of measuring adhesion. However, they do not reveal the underlying biophysical mechanisms of cell-cell interaction that might be critical in determining how well IRBCs remain adherent to microvascular endothelium under high shear stress once they are recruited to the vessel wall. In this study, we performed single-cell force spectroscopy with atomic force microscopy (AFM) in combination with confocal microscopy to determine for the first time the dynamics of IRBC-endothelial cell interaction in real time. Our findings revealed a novel adhesive mechanism that links CD36 and the actin cytoskeleton via Src family kinases and the adaptor protein p130CAS in endothelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue culture and other reagents

Unless otherwise stated, all tissue culture reagents were obtained from Invitrogen Canada (Burlington, ON, Canada), and chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The Src-family kinase inhibitor PP1 and the inactive analog PP3 were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences International (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Chemiluminescence HRP substrate was purchased from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA, USA).

Antibodies

The following mAbs were used: anti-human CD36, clone FA6-152 (Beckman Coulter Canada, Mississauga, ON, Canada); anti-human ICAM-1, clone 84H10 (Beckman Coulter); anti-human p130CAS, clone 21/p130[Cas] (BD Biosciences, Mississauga, ON, Canada); and mouse IgG1, clone 11711 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Polyclonal antibodies used included anti-phospho-p130CAS (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), anti-phospho-Tyr418Src (BioSource; Invitrogen), and anti-His-tag (His-probe [H-15]; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Alexa Fluor 488 or 568 goat anti-mouse IgG1 antibodies and rhodamine-phalloidin were from Molecular Probes (Invitrogen). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA, USA).

Parasites

Unless otherwise stated, experiments were performed with the parasite line 7G8, which binds to both CD36 and ICAM-1. The stock culture was shown to be free of mycoplasma contamination by RT-PCR (MycoAlert; Lonza Walkersville, Walkersville, MD, USA). Frozen aliquots were thawed and cultured for 24–30 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 until the late trophozoite/early schizont stage, as determined by light microscopy. IRBC cultures were used in single experiments and then discarded.

Experiments were also performed with cryopreserved clinical parasite isolates obtained from adult Thai patients with acute falciparum malaria at the Hospital for Tropical Medicine (Bangkok, Thailand; ref. 15). The collection of specimens was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (Bangkok, Thailand). Informed consent was obtained from all patients and/or relatives according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Microvascular endothelial cells

Primary human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (HDMECs) were harvested from discarded neonatal human foreskins using 0.5 mg/ml type IA collagenase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) as described previously (15). The collection of skin specimens was approved by the Conjoint Ethics Board of Alberta Health Services and the University of Calgary (Calgary, AB, Canada). Harvested cells were seeded in 60-mm dishes in endothelial basal medium (EBM; Lonza) with supplements provided by the manufacturer. When cells were confluent, they were further purified on a MACS column using CD31-coated beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA, USA). Only cell preparations that were >95% positive for CD36 expression by flow cytometry were maintained for experiments. Experiments were performed with cells from passages 2 to 5 that were demonstrated to consistently support IRBC adhesion (15).

Transduction of HDMECs with adeno-CD36-GFP

GFP-labeled CD36 was produced using the AdEasy adenoviral system (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). The selected recombinant was used to transfect HEK293 cells where deleted viral assembly genes were complemented in vivo. Harvested virus titers were adjusted to 1.0 × 1010 plaque-forming units (PFU)/ml. Viruses with the adeno-GFP construct were used as the control. Transduction was carried out using 1.0 × 107 PFU/ml. The recombinant adenoviruses were routinely tested for the presence of endotoxin using the Kinetic QCL Limulus Amebocyte Lysate assay (Lonza) and contained <0.3 endotoxin units/ml. Expression of CD36 on these cells was confirmed by both immunofluorescence and flow cytometry.

Small interference RNA (siRNA) for p130CAS

HDMECs were seeded at 1 × 105 cells/well of 12-well plates and transfected 24 h later at ∼60% confluence. At the time of transfection, the medium was aspirated and replaced with 0.5 ml of OptiMEM. The transfection mixture of 5 μl HiPerfect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and 20 nM siRNA for p130CAS or 20 nM AllStars Negative Control (Qiagen) was added in 50 μl of OptiMEM. At 4 h after transfection, 0.5 ml of EBM was added to each well. Transfected cells were trypsinized after 24 h and seeded into 35-mm dishes at 1 × 105 cells/dish for flow chamber experiments after a further 48 h. Transfected cells were also seeded on 25-mm glass coverslips for AFM experiments (see below). Cell lysates were used to confirm gene knockdown by Western blot analysis.

PpMC-179 and antibody-coated beads

The recombinant PpMC-179 protein representing the minimal binding domain of PfEMP1 (residues 88–267 of the CIDR domain of the parasite strain Malayan Camp) for CD36 (16) with a His6 tag on the C terminus was used to coat carboxyl functionalized polystyrene beads with a diameter approximating that of red blood cells (6.37±0.37 μm; Bangs Laboratories, Fishers, IN, USA). The preparation and purification of the recombinant protein expressed in Pichia pastoris was described previously (17). Beads were first covalently coated with an anti-His-tag antibody according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Briefly, beads (25 μl) were washed in PBS before incubation with 1 ml of 1M cyanamide solution for 15 min. Beads were washed in coupling buffer (0.1M borate buffer, pH 8.0) and resuspended in 25 μg of anti-His-tag antibody and incubated overnight at 4°C on a rotating rocker. After the incubation, beads were washed in coupling buffer and stored in 25 mM glycine both to block nonspecific binding and to reduce autofluorescence. Prior to being used, the beads were washed in PBS and resuspended at a ratio of 1 μl beads to 1 μg PpMC-179 peptide in 20 μl PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Coated beads were washed extensively with PBS to remove unbound peptide from the beads. The presence of PpMC-179 on the beads was confirmed by Western blot.

Polystyrene beads were also coated with FA6–152, a mAb known to inhibit IRBC binding to CD36 (15). Antibody (1 μg) in 10 μl PBS was added to 1 μl of beads for 2 h on a rocker and then let stand for 1 h. After washing in PBS, the beads were blocked with 100 μl of 0.1% BSA/PBS for 30 min. Beads were used within 48 h of preparation. The presence of antibody on the beads was confirmed by flow cytometry using goat-anti-mouse IgG-Alexa 488. Mouse IgG1-coated beads were used as controls.

Confocal microscopy

HDMECs were seeded into chambered slides (μ-slideVI0.4; Ibidi GmbH, Munich, Germany) at 2 × 104 cells/chamber. When cells were 95% confluent (48 h), they were transduced with GFP-CD36. For live-cell imaging, MACS-purified IRBCs at 0.1% hematocrit were added to the chamber 24 h after transduction. IRBC and HDMEC interaction was imaged in an enclosed, humidified chamber maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. For experiments with antibody or peptide-coated beads, 0.5 μl of antibody- or peptide-coated beads resuspended in 60 μl HBSS were incubated with monolayers at 37°C and 5% CO2 for 30 min. After unbound beads were removed with HBSS, the monolayers were fixed with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature. They were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min, blocked with 1% BSA plus 0.003% Triton X-100, and stained with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight, followed by rhodamine-phalloidin (1:60) for 1 h at room temperature. All images were taken on an Olympus IX81 inverted confocal microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) with Fluoview 1000 acquisition software using a PlanAPO ×60 oil-immersion objective (NA 1.42).

Quantification of CD36 and actin clustering was performed by randomly selecting 3 microscopic fields at ×60 magnification. Except for IgG- or anti-His-tag-coated beads, each field contained an average of 15 to 20 beads. Adherent beads associated with diffused fluorescence or discrete fluorescent rings were scored as positive by a blinded observer. Beads that were partially visible in the field were excluded. Results are expressed as percentage beads positive for protein recruitment.

Flow chamber assay

A modified flow chamber assay was performed using a parallel plate flow chamber system, as described previously (15). IRBCs in RPMI (1% hematocrit and 5% parasitemia) were allowed to adhere to an HDMEC monolayer in a 35-mm dish, with or without pretreatment with various inhibitors, for 20 min at 37°C. A static assay was performed in order to bring IRBCs and HDMECs together without modification of the cytoskeleton by shear stress. At the end of the incubation, the monolayer with adherent IRBCs was mounted into a flow chamber. HBSS was pulled through at 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 dyn/cm2 at 1-min intervals. Experiments were recorded and analyzed offline. The number of adherent IRBCs at each shear stress was enumerated and expressed as a percentage of the number at 1 dyn/cm2.

Single-cell force spectroscopy

Force spectroscopy was performed using a Nanowizard II atomic force microscope equipped with a CellHesion Module (JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany). The microscope was mounted on the stage of a Zeiss Axiovert 200 inverted light microscope (Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA); the instruments were enclosed in a humidified chamber maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Force measurements were obtained using relative contact mode with a relative set point of 150 pN, extend/retract rates of 1.5 μm/s, Z length of ∼50 μm, and sample rate of 256 Hz. The baseline vertical offset was adjusted prior to every AFM reading, and the software was set to correct for nonlinearity and hysteresis of the piezo. Analysis of data to determine the maximum detachment force and the number of rupture events was performed using software provided by JPK Instruments.

Force measurement experiments were performed with 2 × 104 HDMECs seeded on one half of a 25-mm round glass coverslip precoated with 0.2% gelatin. At the time of confluence (48 h), the coverslip was loaded into a custom-built liquid cell that allowed the force measurements to be performed in fluid phase. The monolayers were washed twice with HBSS. A volume of 1 μl of IRBCs at 0.5% hematocrit and 5 to10% parasitemia was added to the half of the coverslip not seeded with HDMECs. The liquid cell was placed on the stage of the inverted microscope. At the start of the experiment, the cantilever that had been functionalized with dopamine hydrochloride (18) was lowered onto an IRBC that was allowed to adhere for 60 s before the cantilever with the adherent IRBC was moved to the monolayer and brought into contact with an endothelial cell.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Data are expressed as means ± se unless otherwise stated. Data from 2 groups were compared using Student's 2-tailed t test for paired samples. Data between groups were compared using a 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by post hoc analysis with Tukey's test. Values of P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Force measurements at single-cell level

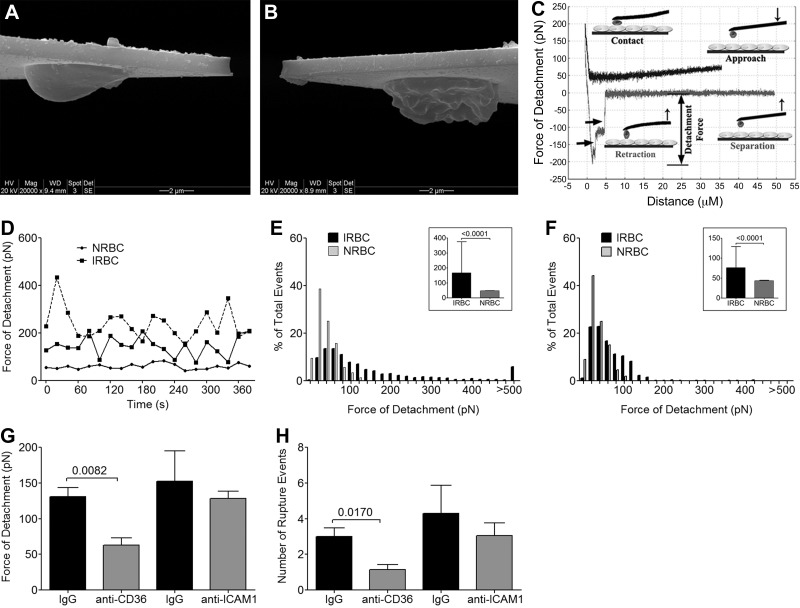

Force measurements between a noninfected red blood cell (NRBC; Fig. 1A) or IRBC (Fig. 1B) attached to the end of an AFM cantilever were performed by bringing the cell into direct contact with the center of an endothelial cell in a confluent monolayer. On contact, the cantilever was retracted, resulting in the generation of a number of stepwise rupture events and the separation of the 2 cells. A typical force curve depicting the principal events during a force vs. distance measurement, that is, approach, contact, retraction, and separation, is shown in Fig. 1C. The detachment force is the maximal force detected by the cantilever during cell-cell separation, while rupture events in the detachment curve represent breakage of adhesive bonds. In all subsequent experiments, the force of detachment and the number of rupture events were used as a measure of the adhesive strength between the IRBC and the endothelial cell.

Figure 1.

Force measurement of initial contact between IRBCs and HDMECs. A, B) NRBC (A) and IRBC (B) mounted on the AFM cantilever were imaged using a Phillips/FEI XL 30 scanning electron microscope. C) Schematic representation of a typical AFM force curve that depicts approach of the IRBC to an endothelial monolayer, contact between IRBC and endothelial cell, retraction of the IRBC, and separation of the IRBC from the endothelial cell. Horizontal arrows indicate rupture events on the force curve. D) Representative force vs. time curves at 20-s intervals of 2 IRBCs and 1 NRBC making contact with a single HDMEC. E) Histogram of the force of detachment for IRBCs, n = 2438, and NRBCs, n = 385. Inset: mean ± sd detachment force of IRBCs vs. NRBCs. F) Histogram of the force of detachment when rupture events are restricted to 0 to 1 (IRBCs, n=658; NRBCs, n=303). G, H) Force of detachment (G) and number of rupture events (H) after HDMEC monolayers were incubated with either anti-CD36 (n=6) or anti-ICAM-1 (n=5) at 5 μg/ml in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C and washed 3× with HBSS before force measurements were taken. In each experiment, mean force of detachment of 40 contacts made by 2 IRBCs with 2 different HDMECs was determined. All of the above experiments were carried out using a contact force of 150 pN, separation speed of 1.5 μm/s, and <1 s contact duration.

Adhesive force for IRBC-HDMEC is CD36-mediated

We began by measuring the initial adhesive force between an IRBC or an NRBC and an HDMEC. In these experiments, an erythrocyte was brought into contact with an endothelial cell using a contact force of 150 pN at a steady velocity of 1.5 μm/s. These parameters were chosen because they approximate the marginating force experienced by a leukocyte as it is pushed from centerline blood flow toward the vessel wall by NRBCs (19). A similar marginating force has been estimated for IRBCs that is more rigid than that for NRBCs (20). On contact, the cantilever was immediately retracted (duration of contact <1 s). Figure 1D shows 2 representative detachment force vs. time curves for repeated contacts of an IRBC on a single HDMEC. A force vs. time curve for an NRBC is included for comparison. The oscillating pattern of the IRBC detachment force on repeated contact indicates that the integrity of the cell membrane and its adhesion molecules remained intact with repeated force-rupture events. This observation validated the use of a single IRBC-HDMEC pair for multiple measurements.

A histogram plotted for 2438 contacts made with 68 IRBCs and 385 contacts for 15 NRBCs showed a single peak distribution with a mean ± sd detachment force of 166.7 ± 208.7 pN for IRBCs and 47.1 ± 26.1 pN for NRBCs (Fig. 1E). Moreover, the number of rupture events for each of the interactions varied, so that no bond, a single bond, or multiple bonds could be formed on each contact. When the force of detachment for events that had 0 or 1 detachment event were plotted, the detachment force dropped to 76.2 ± 53.1 pN (Fig. 1F), similar to detachment forces reported for single bonds for a number of hematopoietic cell types with endothelium (21).

To determine whether the initial contact between IRBCs and HDMECs is receptor dependent, monolayers were preincubated with the anti-CD36 mAb FA6-152 or anti-ICAM-1 mAb 84H10. As shown in Fig. 1G, H, anti-CD36 significantly reduced the mean force of detachment and the number of rupture events, while anti-ICAM-1 had no effect.

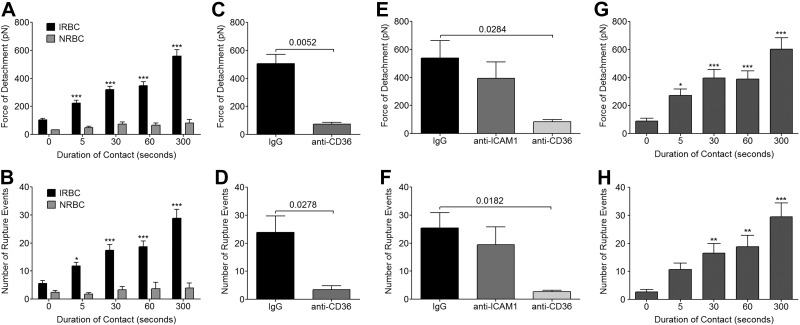

Increase in binding force with duration of contact

When an IRBC was kept in contact with an HDMEC using a constant force of 150 pN as controlled with the Cellhesion module of the atomic force microscope, a progressive increase in detachment force from 105.0 ± 10.6 pN at <1 s to 559.3 ± 45.5 pN after 300 s was observed (Fig. 2A). There was a parallel increase in the number of rupture events, from 5.6 ± 1.1 to 28.8 ± 3.2 (Fig. 2B). This effect was specific to IRBCs, as no increase in either parameter was seen with NRBCs. As well, no increase in detachment force was observed on monolayers that had been fixed in 1% PFA for 30 min at room temperature (data not shown), suggesting that modification and/or mobility of the molecules involved was essential. As with the initial contact, the increase in detachment force and number of rupture events with prolonged contact was mediated largely by CD36 (Fig. 2C, D), even when an HDMEC was stimulated with TNF-α to up-regulate ICAM-1 expression (Fig. 2E, F).

Figure 2.

Effect of prolonged contact on adhesive strength of IRBC-HDMEC interaction. A single IRBC was held in contact with a single HDMEC for increasing durations from <1 s to 300 s. A, B) Force of detachment (A) and number of rupture events (B) at different time points for parasite clone 7G8. Results are from n = 47 for IRBCs, n = 4 for NRBCs. C, D) Force of detachment (C) and number of rupture events (D) for HDMEC monolayers that were preincubated with anti-CD36 at 5 μg/ml in HBSS for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 (n=4). E, F) Force of detachment (E) and number of rupture events (F) for HDMEC monolayers that were stimulated with 20 ng/ml TNF-α overnight prior to preincubation for 30 min at 37°C with either anti-CD36 or anti-ICAM-1 (200 μl of antibody at 5 μg/ml in HBSS; n=6). G, H) Force of detachment (G) and number of rupture events (H) for 3 different clinical isolates (n=7). For each experiment, 1 IRBC was brought into contact with 2 HDMECs. Contact was maintained with a maximum contact force of 150 pN. Results were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test (A, B, G, H) or by Student's t test for paired samples (C–F). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

To ensure that the above results are representative of parasite isolates obtained directly from patients with acute infections, experiments were performed with clinical isolates during the first cycle in culture (Fig. 2G, H). As with the laboratory-adapted 7G8 parasites, the force of detachment for 3 clinical isolates increased from 88.8 ± 20.7 to 603.9 ± 80.5 pN over 300 s. There was a parallel increase in the number of detachment events, from 2.7 ± 0.8 to 29.5 ± 5.1.

Role of Src family kinases and ecto-alkaline phosphatase in IRBC-HDMEC binding

We have previously shown an essential role for Src family kinases in increasing the numbers of IRBCs that adhere to the endothelium in bulk flow in a flow chamber assay through activation of surface alkaline phosphatase and subsequent dephosphorylation of the ectodomain of CD36 (11, 12). To determine whether Src family kinases also have a role in regulating the increase in adhesive strength with duration of contact, HDMEC monolayers were pretreated with the inhibitor PP1. Inhibition of Src family kinases resulted in a reduction of the force of detachment from 554.2 ± 146.5 to 196.0 ± 75.5 pN (Fig. 3A) and reduced the number of rupture events from 31.9 ± 10.1 to 8.0 ± 2.5 (Fig. 3B). The inactive analog PP3 had no effect. A reduction in adhesive strength was also observed when HDMECs were treated with the specific alkaline phosphatase inhibitor levamisole. The force of detachment was reduced from 518.5 ± 138.2 to 153.4 ± 45.9 pN (Fig. 3C), but there was no significant difference in the number of rupture events (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Role of Src family kinases, alkaline phosphatase, actin cytoskeleton, and intracellular Ca2+ on the enhancement of adhesive strength with time. A, B) Force of detachment (A) and number of rupture events (B) at different time points for HDMEC monolayers that were preincubated with DMSO, PP3, or PP1 at a concentration of 10 μM for 2 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 (n=5). C, D) Force of detachment (C) and number of rupture events (D) for HDMEC monolayers that were preincubated with medium or 500 μM levamisole. E, F) Force of detachment (E) and number of rupture events (F) for HDMEC monolayers that were preincubated with 1 μM cytochalasin D for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 (n=5). G, H) Force of detachment (G) and number of rupture events (H) for HDMEC monolayers that were preincubated with the BAPTA-AM for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2 (n=5). All inhibitors, with the exception of levamisole (duration of action ∼ 10 min after removal), were removed and the monolayers were rinsed with HBSS before force measurements. Each experiment consisted of the interaction between 1 IRBC and 2 HDMECs. Contact for 300 s was maintained with a maximum contact force of 150 pN. Results were analyzed using Student's t test for paired samples.

Enhancement of detachment force is inhibited by cytochalasin D and is calcium dependent

Leukocyte adhesion to endothelium is associated with the activation of intracellular signaling pathways, leading to calcium flux, protein phosphorylation, and cytoskeletal modifications (22). To determine whether changes in the actin cytoskeleton of HDMECs occur as a result of IRBC cytoadherence, and whether the changes contribute to the enhancement of detachment force that was seen on prolonged contact of IRBCs on HDMECs, monolayers were pretreated with 1 μM of cytochalasin-D for 30 min. Preliminary experiments indicated that the effect of cytochalasin on the actin cytoskeleton in HDMECs was maintained for up to 30 min after the removal of the inhibitor (Supplemental Fig. S1A–F). Cytochalasin-D inhibited the increase in detachment force with time but not rupture events (Fig. 3E, F). In contrast, colchicine, an inhibitor of microtubule polymerization, had no effect on detachment force (data not shown). The enhancement of adhesive strength was calcium dependent, as it was abrogated in the presence of the intracellular calcium chelator BAPTA-AM (Fig. 3G, H).

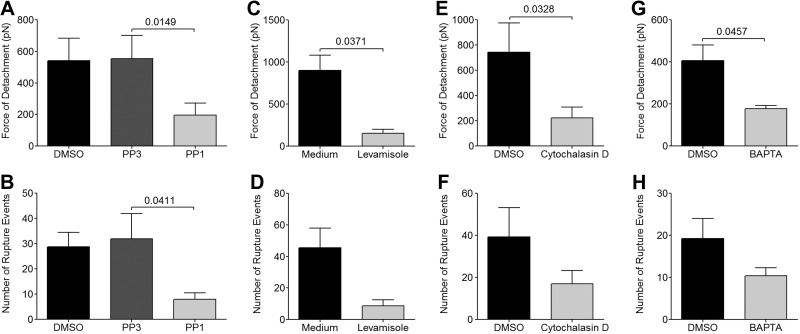

Recruitment of CD36 and actin to site of IRBC adhesion

The above findings suggested that the enhancement of binding avidity of IRBCs on HDMECs is dependent on the activation of an intracellular signaling cascade initiated by the engagement of CD36 by IRBCs that is linked to the remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Such a signaling pathway involving the phosphorylation of Src family kinases and Crk-associated substrate (p130CAS) has been described for the ligation of CD36 on microglial cells by fibrillar β-amyloid (23). As the readout from the AFM experiments was limited to force measurements, we next used confocal microscopy to visually assess whether a similar pathway was initiated by CD36 engagement by IRBCs on HDMECs. Specifically, we examined the induction of receptor clustering and actin recruitment to the site of adhesion, and the phosphorylation of Src family kinases and its substrate p130CAS in the process.

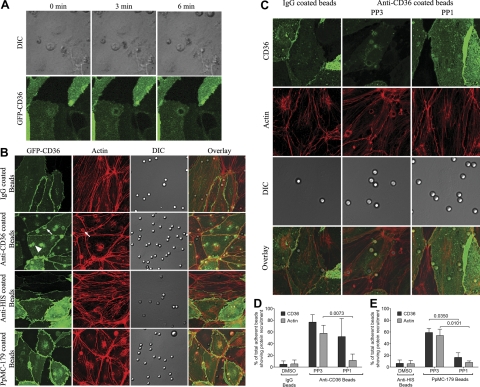

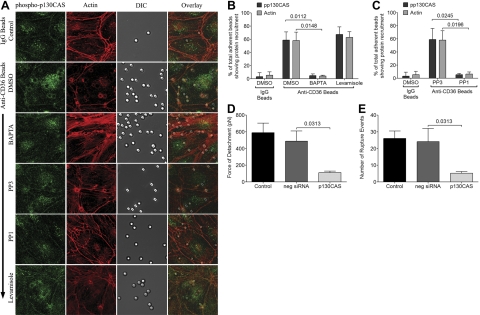

Live-cell imaging of IRBCs, purified on a MACS column, that had adhered to GFP-CD36-transduced HDMECs was performed. Figure 4A shows that GFP-CD36 was recruited to the site of IRBC adhesion within minutes of the adhesion process. Because of the technical difficulty with examining a large number of IRBCs by live-cell imaging, and limitations in visualizing IRBC-HDMEC interactions due to artifacts associated with the fixation of adherent IRBCs on endothelial monolayers, subsequent experiments were performed with antibody-coated beads, as have been used to study leukocyte-ICAM-1 interaction on endothelial cells (24). Beads coated with recombinant parasite peptide PpMC-179 were also used. The presence of antibody or PpMC-179 on the beads was confirmed by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. S3A) and Western blot (Supplemental Fig. S3B), respectively. Force measurements by AFM confirmed that both types of beads bound to HDMECs (Supplemental Fig. S3C–E). As with live IRBCs, the adhesion of antibody and peptide-coated beads to GFP-CD36-transduced HDMECs led to CD36 recruitment to the site of attachment of the beads (Fig. 4B). Moreover, actin was also seen to be recruited to the same sites. Recruitment of actin but not CD36 by antibody-coated beads was inhibited by PP1, while recruitment of both proteins by PpMC-179-coated beads was inhibited by PP1 (Fig. 4C). Quantification of the microscopy findings for both types of beads is shown in Fig. 4D, E.

Figure 4.

Endothelial CD36 and actin recruitment by adherent IRBCs or antibody- or PpMC-179-coated beads. HDMECs were grown to 95% confluence in Ibidi VI chambers before being transduced with an adenoviral vector containing a GFP-CD36 construct. Monolayers were used 24 h after transduction. A) IRBCs purified on MACS were added to a monolayer at 0.1% hematocrit. IRBC interaction with HDMECs was imaged in a humidified chamber with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Results are representative of 2 experiments. B) HDMEC monolayers in Ibidi chambers transduced with GFP-CD36 were incubated with beads coated with IgG, anti-CD36, anti-His-tag, or PpMC-179 for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Monolayers were washed 2 times with HBSS to remove unbound beads prior to fixing with 1% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. Monolayers were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 5 min and blocked with 1%BSA + 0.003%Triton X-100. Actin cytoskeleton was visualized by adding 1 μl of rhodamine-phalloidin in 60 μl of HBSS to each chamber for 30 min at room temperature. Arrowheads indicate representative sites of diffuse CD36 or actin recruitment; arrows indicate ringlike recruitment. Results shown are representative of 3 experiments. C) HDMEC monolayers transduced with GFP-CD36 were treated with 10 μM of PP1 or PP3 at 37°C for 2 h before the addition of antibody-coated beads. Results shown are representative of 5 experiments. Images shown represent a z projection of 0.3-μm stacks. Original magnification ×600 and zoom ×3. D, E) Quantification of microscopic changes. Three randomly selected microscopic fields with original magnification ×600 and zoom ×2, each with 15–20 adherent beads, were scanned, and adherent beads associated with protein recruitment were scored as positive. Results are expressed as percentage positive beads. D) Antibody-coated beads (n=5). E) PpMC-179-coated beads (n=3).

CD36 engagement induces localized phosphorylation of Src family kinases and p130CAS

To demonstrate the effect of CD36 engagement on Src family kinases and p130CAS, antibody-coated beads were allowed to adhere to untransduced HDMECs and then fixed. Fixed monolayers were stained with anti-phospho-Src and anti-phospho-p130CAS antibodies. Localized recruitment of phospho-Src (Fig. 5A) and phospho-p130CAS (Fig. 6A) to the sites of bead adhesion was seen. The phosphorylation of p130CAS was inhibited by PP1, suggesting that it is downstream of Src family kinases. Phosphorylation of both kinases and p130CAS were calcium dependent, as it was abrogated in the presence of BAPTA-AM. Interestingly, the specific alkaline phosphatase inhibitor levamisole had no effect on either the phosphorylation of Src family kinases or p130CAS, or the recruitment of actin to the site of adherent cells, indicating that its effect on adhesive strength was mediated by an entirely different mechanism. The microscopic findings were quantified in Figs. 5B, C and 6B, C.

Figure 5.

Localized phosphorylation of Src family kinases as a result of CD36 engagement. A) HDMEC monolayers were pretreated with inhibitors as described in Fig. 3. Anti-CD36-coated beads were then added to the monolayers for 30 min at 37°C in 5% CO2. Monolayers were washed 2× with HBSS to remove unbound beads prior to fixing with 4% PFA for 20 min at room temperature. Monolayers were permeabilized with 0.2% Tx-100 for 5 min and blocked with 1%BSA + 0.003% Tx-100 prior to staining with anti-phospho-Src overnight at 4°C, followed by goat-anti-rabbit IgG-Alexa 488 for 1 h at room temperature. Actin cytoskeleton was visualized by adding 1 μl of rhodamine-phalloidin in 60 μl HBSS to each chamber for 30 min at room temperature. Images were taken as in Fig. 4. Results shown are representative of 3 experiments. B, C) Quantitation of microscopic changes was performed as for Fig. 4. B) Effect of BAPTA-AM and levamisole on phospho-Src and actin recruitment by anti-CD36-coated beads (n=3). C) Effect of PP1 and PP3 on phospho-Src and actin recruitment by anti-CD36-coated beads (n=3).

Figure 6.

Localized phosphorylation of p130CAS as a result of CD36 engagement. A) HDMEC monolayers were prepared as in Fig. 5. Fixed monolayers with adherent beads were stained with anti-phospho-p130CAS. B, C) Quantitation of microscopic changes was performed as for Fig. 4. B) Effect of BAPTA-AM and levamisole on phospho-Src and actin recruitment by anti-CD36-coated beads (n=3). C) Effect of PP1 and PP3 on phospho-Src and actin recruitment by anti-CD36-coated beads (n=3). D, E) Force of detachment (D) and number of rupture events (E) of IRBCs on control HDMECs, and HDMECs transfected with negative siRNA and p130CAS siRNA.

Endothelial p130CAS activity is required for enhancement of binding

To more specifically assess the role of p130CAS in the increase in detachment force of IRBCs, we performed gene knockdown of p130CAS in HDMECs by siRNA. Loss of p130CAS protein production was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Supplemental Fig. S3A, B). The targeted deletion of p130CAS was specific and did not alter endothelial CD36 expression (Supplemental Fig. S3C). The loss of p130CAS led to a reduction in the detachment force from 487.8 ± 121.9 to 111.6 ± 17.2 pN (Fig. 6D) as well as the number of rupture events from 24.1 ± 8.0 to 5.3 ± 1.0 (Fig. 6E).

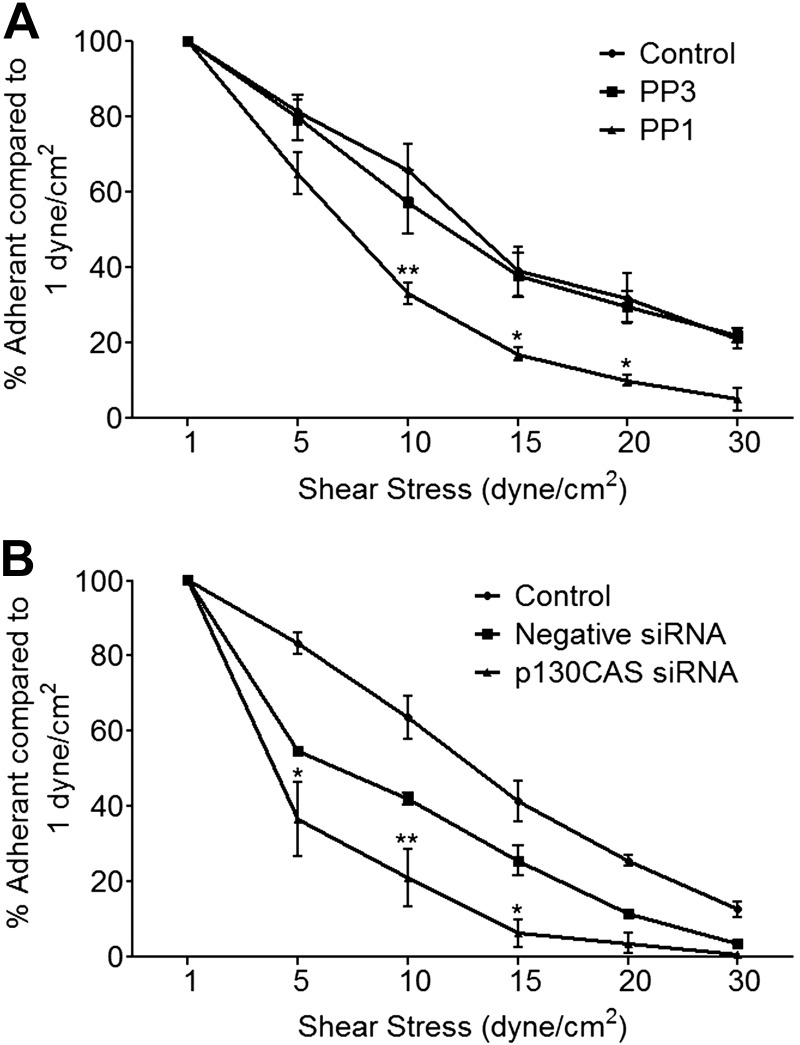

Increased adhesion force enables adherent IRBCs to withstand high shear stress

To be physiologically relevant, the increase in adhesive strength with time should enable an IRBC to withstand the high shear stress present in the microcirculation after the initial attachment. This was tested in a modified flow chamber assay in which adherent IRBCs on control HDMECs or HDMECs that had been pretreated with PP1 or in which p130CAS expression had been knocked down by siRNA were subjected to increasing shear stress. In a previous study, we demonstrated that IRBC adhesion under shear stress was maximal at 1 dyn/cm2 and dropped off rapidly as shear stress was increased (15). However, once adherent, IRBCs could withstand shear stresses of up to 10 dyn/cm2. In the detachment assay in this study, IRBCs were again seen to remain adherent at shear stress ≥ 5 dyn/cm2, but the number of adherent IRBCs was significantly higher on control compared to PP1-treated (Fig. 7A) or p130CAS-deficient (Fig. 7B) cells.

Figure 7.

Role of Src family kinases and p130CAS in resistance of IRBCs to detachment under shear stress. HDMECs in 35-mm dishes were either pretreated with 10 μM PP1 or PP3 for 2 h at 37°C (A) or transfected with negative siRNA or siRNA for p130CAS (B). At the time of experimentation, IRBCs at 1% hematocrit and 5% parasitemia in 1 ml RPMI were added to each monolayer for 30 min to allow IRBCs to adhere. Dishes were then incorporated into a parallel plate flow chamber. HBSS was perfused at 1 dyn/cm2 for 2 min to remove nonadherent IRBCs. Shear stress was then increased each minute to 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 dyn/cm2. At each shear stress, numbers of adherent IRBCs were counted and expressed as a percentage of the number of adherent IRBCs at 1 dyn/cm2. Results between cells treated with PP1 and PP3, and cells transfected with negative and p130CAS siRNA, were compared using 2-way ANOVA with post hoc analysis using Bonferroni's test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (n=3).

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated that endothelial CD36 provides more than just an attachment point for the malaria parasite, and that IRBC interaction with CD36 leads to intracellular signaling within the host endothelium (11). To further explore the mechanisms that promote CD36 signaling following cytoadherence, we employed AFM and confocal microscopy in this study to examine the molecular events subsequent to adhesion at the single-cell level. AFM alone has been used to study the adhesive forces between IRBCs and recombinant CD36 and TSP-1 immobilized on the cantilever by antibodies (25). The use of recombinant receptor proteins is convenient but does not allow for the investigation of cellular events that are triggered by the adhesion process. Even as a means of studying the role of a single adhesion molecule, the method is limited by the fact that the receptor is displayed in an undefined orientation, whereas cell-cell interactions are more likely to be mediated by molecules displayed in their biological context. In addition, adhesive force is dependent on receptor density that may be many folds higher for purified proteins compared to live cells.

We found that CD36 engagement by IRBCs, or antibody- or parasite peptide-coated beads, led to localized phosphorylation of Src family kinases and p130CAS, actin cytoskeletal rearrangement, and recruitment of CD36 to the site of adhesion. The resulting increase in adhesive strength was evident within minutes of cell contact. Unlike cognate ligands of CD36 that trigger internationalization of the ligand-receptor complex in other cell types (26), neither IRBCs nor the antibody/peptide-coated beads were internalized by HDMECs. As a result, the triggering of signaling events and accumulation of CD36 molecules in HDMECs most likely occurred on the cell surface. How surface-expressed CD36 is recruited on endothelial cells is not known. However, a direct link between membrane CD36 clustering and the organization of the actin cytoskeleton has been elegantly demonstrated in primary human macrophages by single-molecule imaging (27). CD36 mobility in macrophages was dependent on the integrity and flow of the cortical actomyosin network, and disruption of the cytoskeleton inhibited ligand internalization and subsequent signaling. Receptor clustering in HDMECs would increase the number of interacting ligand-receptor pairs, as demonstrated by the increase in both the detachment force and number of rupture events detected by AFM with the duration of contact. In HDMECs, CD36 as well as actin recruitment induced by peptide-coated beads was Src family kinase dependent. However, the effect on CD36 recruitment was not seen with antibody-coated beads, which may be due to the fact that a reduction in CD36 recruitment is difficult to detect visually when a strong stimulus is used.

The AFM results also suggested that the signaling pathway involving Src family kinases activated downstream of CD36 engagement has at least 2 targets that affect the avidity of IRBC adhesion. First, as shown previously for IRBC adhesion in bulk flow, part of the effect of Src family kinases appeared to be mediated through cell surface alkaline phosphatase. The detachment force was reduced by the stereospecific enzyme inhibitor levamisole, but the number of rupture events was unaltered, suggesting that the increase in strength was due to a change in affinity between CD36 and PfEMP1 and not the formation of additional ligand-receptor pairs. As phosphate groups carry a strong negative charge, their removal from the ectodomain of CD36 may allow greater adhesive interactions to occur.

A second consequence of Src activation is the downstream effect on p130CAS and the actin cytoskeleton. p130CAS is a scaffolding or adaptor protein at focal adhesions that has been shown to play an important role in the endothelial response to a number of stimuli, including shear stress (28) and ICAM-1 ligation prior to leukocyte transendothelial migration (29). Moreover, through its association with focal adhesion complexes, p130CAS promotes migration of microglial cells in response to β-amyloid (23) and the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in the process of angiogenesis (30), as well as the migration and invasiveness of tumor cells (31). A potential role for CD36-mediated assembly of p130CAS complexes in the activation of proinflammatory responses in macrophages has also been suggested (23). This notion would be consistent with our previous finding that CD36 crosslinking by antibody or ligation by PpMC-179 led to MAPK and ERK1/2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells (11). The multiple roles of Src family kinases provides a likely explanation for why PP1 had a greater effect on adhesion strength than either levamisole or cytochalasin D alone.

Evidence of a link between IRBCs and endothelial actin cytoskeleton has only been described recently (32). IRBCs adherent to an immortalized human brain endothelial cell line were found to be nearly engulfed by membrane protrusions enriched in ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and actin. Similar observations have been made with leukocytes or LFA-1-expressing transfectants on primary HUVECs (24, 33, 34). Actin-dependent transfer of IRBC membrane to endothelial cells was also said to occur, a process likened to the trogocytosis described for the exchange of membrane materials between antigen-presenting cells and T cells at the immunological synapse (35). The primary microvascular endothelial cells used in the current study had a thickness of <2 μm, making it very difficult to perform vertical Z sections to determine whether the rings of CD36 and actin seen in the cells actually protruded from the cell surface. Extension of endothelial cells around an adherent IRBC has occasionally been seen by electron microscopy in postmortem tissues from patients who died from malaria (3), although neither the frequency of occurrence in vivo nor the structural makeup of the extensions has been investigated.

In addition to promoting receptor molecule clustering, actin cytoskeletal rearrangement may lead to changes in cell shape, and hence the surface area of endothelial cells and receptor density in contact with IRBCs. The use of sideview confocal microscopy in conjunction with AFM would allow for changes in cell shape and movement of labeled cellular proteins to be visualized while force measurements are being made (36). Interestingly, cytochalasin-D had no effect on IRBC recruitment, as determined in the flow chamber assay (unpublished results), suggesting that cytoskeletal rearrangement may have a more important role in determining the strength of the postadhesion interaction between IRBCs and endothelial cells than in the adhesion in bulk flow.

In keeping with our previous findings, IRBCs preferentially bind to CD36 on HDMECs that express both CD36 and ICAM-1 (15) and initiate intracellular signaling events through Src family kinases (11, 12). However, it is likely that ICAM-1-binding parasites would activate similar signaling pathways on microvascular endothelium with patchy or low CD36 expression, such as in the cerebral circulation (3). Engagement of ICAM-1 by antibody-coated beads on HUVECs that do not express CD36 has been shown to induce Src- and Pyk2-dependent phosphorylation of the junctional protein VE-cadherin, which promotes neutrophil transmigration via the paracellular pathway (24). The activation of p130CAS in HUVECs downstream of ICAM-1 ligation has also been reported (29). These findings point to a common pathway of endothelial cell activation that could be targeted to disrupt IRBC adhesion to multiple endothelial cell receptors.

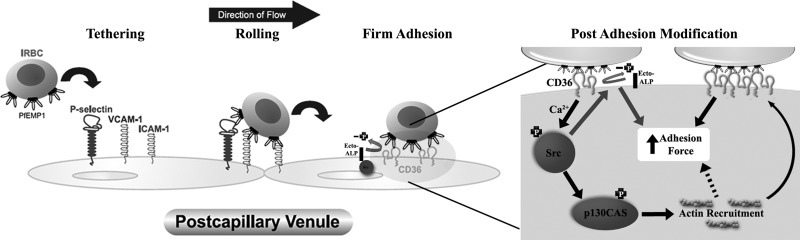

In summary, we have determined the biophysical forces underlying the interaction between IRBCs and HDMECs, and the cellular events that contribute to the enhanced adhesive force with prolonged contact. The findings extend our previous paradigm of the adhesion cascade that mediates the recruitment and adhesion of IRBCs under physiological flow conditions in vitro (15) and in vivo (37, 38) (Fig. 8). As a result of the postadhesion modifications in endothelial cells, IRBCs are better able to withstand shear stress in the microcirculation, providing both a survival advantage for the parasites and a detrimental effect on the host. Single-cell-force spectroscopy using AFM combined with confocal microscopy proved to be a novel and quantitative technique to unravel the mechanisms of the adhesive interaction between IRBCs, and would provide an excellent experimental approach for studying the interaction between IRBCs and other host cells, such as dendritic cells and macrophages.

Figure 8.

Proposed model of the regulation of IRBC adhesion to CD36 on HDMECs. IRBCs are recruited to endothelium under physiological flow conditions in a cascade of adhesive events involving multiple adhesion molecules. Once CD36 is engaged, enhancement of the adhesive strength between IRBCs and HDMECs occurs through activation of Src family kinases and the adaptor protein p130CAS in a calcium-dependent manner, leading to actin cytoskeletal remodeling and CD36 clustering. A second effect of Src family kinase activation is the dephosphorylation of Thr92 in the ectodomain of CD36 by surface-expressed alkaline phosphatase, which also contributes to adhesive strength.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant (MT14104) to M.H. and a group grant (MGC-48374) from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). M.H. is a scientist and D.A.M. is a senior scholar of Alberta Innovates–Health Solutions, Canada. M.R.G. is supported by a CIHR M.D./Ph.D. studentship. The authors are grateful to Dr. Carolyn Lane (Valley View Family Practice Clinic, Calgary, AB, Canada) for providing skin specimens, Dr. Ciaran Brady [National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NAIAD), U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA] for the PpMC-179 peptide, Dr. Dror I. Baruch (NAIAD) for the mAb (clone 4B3) against PpMC-179, Dr. Richard M. Fairhurst (NAIAD) for the parasite line 7G8, and Dr. John F. Elliott (University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB, Canada) for the human CD36 plasmid.

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

- AFM

- atomic force microscopy

- EBM

- endothelial basal medium

- HDMEC

- human dermal microvascular endothelial cell

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IRBC

- infected red blood cell

- NRBC

- noninfected red blood cell

- PfEMP1

- P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1

- TSP-1

- thrombospondin-1.

REFERENCES

- 1. Marchiafava E., Bignami A. (1894) On summer-autumn malarial fevers. In Two Monographs on Malaria and the Parasites of Malarial Fevers, pp. 1–232, New Sydenham Society, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rowe J. A., Claessens A., Corrigan R. A., Arman M. (2009) Adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to human cells: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 11, e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. MacPherson G. G., Warrell M. J., White N. J., Looareesuwan S., Warrell D. A. (1985) Human cerebral malaria: a quantitative ultrastructural analysis of parasitized erythrocyte sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 119, 385–401 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Turner G. D., Morrison H., Jones M., Davis T. M. E., Looareesuwan S., Buley I. D., Gatter K. C., Newbold C. I., Pukritayakamee S., Nagachinta B., White N. J., Berendt A. R. (1994) An immunohistochemical study of the pathology of fatal malaria. Evidence for widespread endothelial activation and a potential role for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 in cerebral sequestration. Am. J. Pathol. 145, 1057–1069 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Silamut K., Phu N. H., Whitty C., Turner G. D., Louwrier K., Mai N. T., Simpson J. A., Hien T. T., White N. J. (1999) A quantitative analysis of the microvascular sequestration of malaria parasites in the human brain. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 395–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dondorp A. M., Ince C., Charunwatthana P., Hanson J., van Kuijen A., Faiz M. A., Rahman M. R., Hasan M., Bin Yunus E., Ghose A., Ruangveerayut R., Limmathurotsakul D., Mathura K., White N. J., Day N. P. (2008) Direct in vivo assessment of microcirculatory dysfunction in severe falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 79–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Warrell D. A., Veall N., Chanthavanich P., Karbwang J., White N. J., Looareesuwan S., Phillips R. E., Pongpaew P. (1998) Cerebral anaerobic glycolysis and reduced cerebral oxygen transport in human cerebral malaria. Lancet 2, 534–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Warrell D. A., White N. J., Phillips R. E. (1985) Pathophysiological and prognostic significance of cerebrospinal fluid lactate in cerebral malaria. Lancet 1, 776–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fairhurst R. M., Baruch D. I., Brittain N. J., Ostera G. R., Wallach J. S., Hoang H. L., Hayton K., Guindo A., Makobongo M. O., Schwartz O. M., Tounkara A., Doumbo O. K., Diallo D. A., Fujioka H., Ho M., Wellems T. E. (2005) Abnormal display of PfEMP-1 on erythrocytes carrying haemoglobin C may protect against malaria. Nature 435, 1117–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cholera R., Brittain N. J., Gillrie M. R., Lopera-Mesa T. M., Diakité S. A. S., Arie T., Krause M.A., Guindo A., Tubman A., Fujioka H., Diallo D. A., Doumbo O. K., Ho M., Wellems T. E., Fairhurst R. M. (2008) Impaired cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes containing sickle hemoglobin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 991–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yipp B. G., Robbins S. M., Resek M. E., Baruch D. I., Looareesuwan S., Ho M. (2003) Src-family kinase signaling modulates the adhesion of Plasmodium falciparum on human microvascular endothelium under flow. Blood 101, 2850–2857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ho M., Hoang H. L., Lee K. M., Liu N., MacRae T., Montes L., Flatt C. L., Yipp B. G., Berger B. J., Looareesuwan S., Robbins S. M. (2005) Ectophosphorylation of CD36 regulates cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum to microvascular endothelium under flow conditions. Infect. Immun. 73, 8179–8187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Asch A., Liu I., Briccetti F., Barnwell J. W., Kwakye-Berko F., Dokun A., Goldberger J., Pernambuco M. (1993) Analysis of CD36 binding domains: ligand specificity controlled by dephosphorylation of an ectodomain. Science 262, 1436–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dondorp A. M., Silamut K., Charunwatthana M., Chuasuwanchai S., Ruangveerayut R., Krintratun S., White N. J., Ho M., Day N. P. J. (2007) Levamisole inhibits sequestration of infected red blood cells in patients with falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 460–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yipp B. G., Anand S., Schollaardt T., Patel K. D., Looareesuwan S., Ho M. (2000) Synergism of multiple adhesion molecules in mediating cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to microvascular endothelial cells under flow. Blood 96, 2292–2298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baruch D. I., Ma X. C., Singh H. B., Bi X., Pasloske B. L., Howard R. J. (1997) Identification of a region of PfEMP1 that mediates adherence of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes to CD36: conserved function with variant sequence. Blood 90, 3766–3775 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yipp B. G., Baruch D. I., Brady C., Murray A. G., Looareesuwan S., Kubes P., Ho. M. (2003) Recombinant PfEMP1 peptide inhibits and reverses cytoadherence of clinical Plasmodium falciparum isolates in vivo. Blood 101, 331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kang S., Elimelech M. (2009) Bioinspired single bacterial cell force spectroscopy. Langmuir 25, 9656–9659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lipowsky H. H. (1995) Leukocyte margination and deformation. In Physiology and Pathophysiology of Leukocyte Adhesion (Granger D. N., Schmid G. W., eds) pp. 140–187, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 20. Imai Y., Nakaaki K., Konda H., Ishikawa T., Lim C. T., Yamaguchi T. (2011) Margination of red blood cells infected by Plasmodium falciparum in a microvessel. J. Biomech. 44, 1553–1558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Helenius J., Heisenberg C. P., Gaub H. E., Muller D. J. (2008) Single cell force spectroscopy. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1785–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nourshargh S, Hordijk P. L., Sixt M. (2010) Breaching multiple barriers: leukocyte motility through venular walls and the interstitium. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 366–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stuart L. M., Bell S. A., Stewart C. R., Silver J. M., Richard J., Goss J. L., Tseng A. A., Zhang A., El Khoury J. B., Moore K. J. (2007) CD36 signals to the actin cytoskeleton and regulates microglial migration via a p130Cas complex. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27392–27401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Allingham M. J., van Buul J. D., Burridge K. (2007) ICAM-1-mediated, Src- and Pyk2-dependent vascular endothelial cadherin tyrosine phosphorylation is required for leukocyte transendothelial migration. J. Immunol. 179, 4053–4064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li A., Lim T. S., Shi H., Yin J., Tan S. J., Li Z., Low B. C., Tan K. S. W., Lim C. T. (2011) Molecular mechanistic insights into the endothelial receptor mediated cytoadherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. PLoS ONE 6, e16929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Collins R. F., Touret N., Kuwata H., Tandon N. N., Grinstein S., Trimble W. S. (2009) Uptake of oxidized low density lipoprotein by CD36 occurs by an actin-dependent pathway distinct from macropinocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 30288–30297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaqaman K., Kuwata H., Touret N., Collins R., Trimble W. S., Danuser G., Grinstein S. (2011) Cytoskeletal control of CD36 diffusion promotes its receptor and signaling function. Cell 146, 593–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okuda M., Takahashi M., Suero J., Murry C. E., Traub O., Kawakatsu H., Berk B. C. (1999) Shear stress stimulation of p130(cas) tyrosine phosphorylation requires calcium-dependent c-Src activation. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26803–26809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Etienne-Manneville S., Manneville J. B., Adamson P., Wilbourn B., Greenwood J., Couraud P. O. (2000) ICAM-1-coupled cytoskeletal rearrangements and transendothelial lymphocyte migration involve intracellular calcium signaling in brain endothelial cell lines. J. Immunol. 165, 3375–3383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaczmarek E., Erb L., Koziak K., Jarzyna R., Wink M. R., Guckelberger O., Blusztajn J. K., Trinkaus-Randall V., Weisman G. A., Robson S. C. (2005) Modulation of endothelial cell migration by extracellular nucleotides. Involvement of focal adhesion kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-mediated pathways. Thromb. Haemost. 93, 735–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Evans I. M., Yamaji M., Britton G., Pellet-Many C., Lockie C., Zachary I. C., Frankel P. (2011) Neuropilin-1 signalling through p130Cas tyrosine phosphorylation is essential for growth factor dependent migration of glioma and endothelial cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 31, 1174–1185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jambou R., Combes V., Jambou M. J., Weksler B. B., Couraud P. O., Grau G. E. (2010) Plasmodium falciparum adhesion on human brain microvascular endothelial cells involves transmigration-like cup formation and induces opening of intercellular junctions. PLoS Pathogens 6, e1001021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carman C. V., Jun C. D., Salas A., Springer T. A. (2003) Endothelial cells proactively form microvilli-like membrane projections upon intercellular adhesion molecule 1 engagement of leukocyte LFA-1. J. Immunol. 171, 6135–6144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yang L., Kowalski J. R., Yacono P., Bajmoczi M., Shaw S. K., Froio R. M., Golan D. E., Thomas S. M., Luscinskas F. W. (2006) Endothelial cell cortactin coordinates intercellular adhesion molecule-1 clustering and actin cytoskeleton remodeling during polymorphonuclear leukocyte adhesion and transmigration. J. Immunol. 177, 6440–6449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Joly E., Hudrisier D. (2003) What is trogocytosis and what is its purpose? Nat. Immunol. 4, 815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chaudhurri O., Parekh S. H., Lam W. A., Fletcher D. A. (2009) Combined atomic force microscopy and side-view optical imaging for mechanical studies of cells. Nat. Meth. 6, 383–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ho M., Hickey M. J., Murray A. G., Andonegui G., Kubes P. (2000) Visualization of Plasmodium falciparum-endothelium interactions in human microvasculature: mimicry of leukocyte recruitment. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1205–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yipp B. G., Hickey M. J., Andonegui G., Murray A. G., Looareesuwan S., Kubes P., Ho M. (2007) Differential roles of CD36, ICAM-1 and P-selectin in Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence in vivo. Microcirculation 14, 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.