Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Children undergoing stem cell transplantation (SCT) are thought to be at risk for increased distress, adjustment difficulties, and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQL). We report results of a multisite trial designed to improve psychological adjustment and HRQL in children undergoing SCT.

METHODS:

A total of 171 patients and parents from 4 sites were randomized to receive a child-targeted intervention; a child and parent intervention; or standard care. The child intervention included massage and humor therapy; the parent intervention included massage and relaxation/imagery. Outcomes included symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress, HRQL, and benefit finding. Assessments were conducted by patient and parent report at admission and SCT week+24.

RESULTS:

Across the sample, significant improvements were seen on all outcomes from admission to week+24. Surprisingly, patients who had SCT reported low levels of adjustment difficulties at admission, and improved to normative or better than average levels of adjustment and HRQL at week+24. Benefit finding was high at admission and increased at week+24; however, there were no statistically significant differences between intervention arms for any of the measures.

CONCLUSIONS:

Although the results do not support the benefits of these complementary interventions in pediatric SCT, this may be explained by the remarkably positive overall adjustment seen in this sample. Improvements in supportive care, and a tendency for patients to find benefit in the SCT experience, serve to promote positive outcomes in children undergoing this procedure, who appear particularly resilient to the challenge.

KEY WORDS: stem cell transplantation, children, depression, posttraumatic stress, resilience

What’s Known on This Subject:

Children undergoing stem cell transplantation are thought to be at risk for increased distress, adjustment difficulties, and impaired health-related quality of life. Few interventions to improve adjustment and quality-of-life outcomes in this setting have been tested.

What This Study Adds:

The excellent outcomes observed in all patient groups, including controls, may be a result of improvements in standard supportive care. Stem cell transplantation may not be as demanding as previously thought to be, and children undergoing this procedure appear resilient to the challenge.

Pediatric cancer has been considered a highly stressful, burdensome, and even traumatic experience for children, leading to expectations of distress and adjustment difficulties1,2; however, research suggests that these children adjust remarkably well.3–6 Most children with cancer experience a period of acute distress and mood disturbance after diagnosis, but only a small subset experiences lingering problems, such as symptoms of depression or posttraumatic stress.1,6–9

Because of the intense demands of stem cell transplantation (SCT), pediatric oncology patients undergoing this procedure are thought to be at higher risk for acute distress and lingering adjustment problems.10–12 Past research has found that children experience high levels of affective and somatic distress at admission for transplantation that escalates after conditioning and then declines, returning to baseline levels by 3 to 6 months after transplantation.12–14 Although the acute distress is transient, it may leave the patient at risk for later adjustment difficulties.10,12 Thus, children undergoing SCT appear to be in greater need of supportive care interventions.

Most pediatric SCT centers offer extensive supportive care and interventions to address patient psychosocial distress.10 A few interventions focused on reducing the distress of parents15,16 have been evaluated; however, child-centered interventions have not. Intervention trials in adult SCT settings have involved complementary therapies, including hypnosis, relaxation/imagery, massage, therapeutic touch, and music therapy.17–20 Benefits have been primarily documented in these trials immediately after intervention, but sustained reductions in distress are not as well established. Improvement in health-related quality of life (HRQL) and benefit finding has been reported from such interventions with adult patients with breast and prostate cancer, with evidence that this is mediated by change in confidence about the ability to relax.21,22

Although SCT is considered a potentially traumatic experience, there is increasing recognition of the human capacity to thrive in face of even the most difficult challenges.23–25 Research has shown that across diverse, potentially traumatic events, including serious illness, most individuals display positive adjustment trajectories or resilience.23–25 There is even evidence that health challenges can lead to psychological growth and benefit finding,26 with some evidence that this might be particularly likely to occur in the pediatric cancer population.27,28

We conducted a randomized, multisite trial testing the benefits of complementary health-promotion interventions designed to reduce distress and promote well-being for children undergoing SCT. The effects of the intervention on the acute distress experienced by patients during transplant hospitalization have been previously reported.29 This article presents findings regarding the efficacy of these interventions on longer-term outcomes of psychological adjustment, HRQL, and benefit finding at 6 months after transplantation.

METHODS

Patients and Settings

Patients were recruited from 4 pediatric SCT centers. Child eligibility included (1) undergoing SCT, (2) anticipated hospital stay of ≥3 weeks, (3) 6 to 18 years of age, and (4) English speaking. Parental eligibility included (1) English speaking and (2) primary, on-site caregiver for the child during hospitalization. Across sites, 242 eligible patients/families were approached; 189 (78.1%) enrolled. A final sample of 171 patients/parents completed all baseline measures, were randomized, and underwent transplantation. Table 1 includes demographic and medical variables of the sample. There were no significant differences between the intervention arms on these variables. More detail regarding the patients and a Consort flow diagram was provided in an earlier report.29 For the outcomes presented here, there was an evaluable sample of 163 at baseline and 97 at week+24. A total of 25 patients died, 11 withdrew, 8 were taken off study for medical reasons (relapse, second transplant), and 22 missed the week+24 assessment. Comparison of participants who did and did not complete week+24 assessments revealed no differences on baseline adjustment measures. There were differences in socioeconomic status (χ2 [3150] = 14.8, P < .01); those in socioeconomic status strata IV and V had a lower completion rate. A marginal difference was also seen by site (χ2 [3, 171] = 10.2 P < .05), with a higher rate of noncompletion at the Toronto site.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Medical Background

| HPI-Child | HPI-Child-Parent | Standard Care | Total | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M = 12.8, SD = 3.9), y, % | |||||

| 6–12 | 46.6 | 48.2 | 52.6 | 49.1 | .79 NS |

| >12 | 53.4 | 51.8 | 47.4 | 50.9 | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male, % | 67.2 | 55.4 | 52.9 | 59.1 | .24 NS |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | |||||

| White | 70.7 | 72.3 | 70.2 | 70.7 | .61 NS |

| Black | 16.5 | 14.3 | 12.3 | 14.6 | |

| Hispanic | 5.2 | 3.6 | 7.0 | 5.3 | |

| Asian | 3.4 | 7.1 | 1.8 | 4.1 | |

| Other/Unknown | 5.1 | 1.8 | 8.8 | 5.3 | |

| Socioeconomic statusa | |||||

| I | 17.2 | 17.9 | 14.0 | 16.4 | .78 NS |

| II | 39.6 | 33.9 | 35.0 | 36.2 | |

| III | 20.7 | 25.0 | 14.0 | 19.8 | |

| IV & V | 15.5 | 12.5 | 22.8 | 16.9 | |

| Unknown | 6.9 | 10.7 | 14.0 | 10.5 | |

| Resident parent | |||||

| Mother | 84.7 | 85.7 | 76.7 | 82.4 | .46 NS |

| Father | 10.2 | 8.9 | 16.1 | 11.7 | |

| Other | 5.1 | 5.4 | 7.1 | 5.8 | |

| Site | |||||

| St Jude | 46.6 | 36.8 | 38.3 | 41.5 | .33 NS |

| HSC-Toronto | 15.5 | 26.1 | 31.6 | 23.9 | |

| CHOP | 24.1 | 19.6 | 19.3 | 20.5 | |

| NCH-Columbus | 13.8 | 17.5 | 10.7 | 14.0 | |

| Type of transplant | |||||

| Autologous | 10.3 | 21.4 | 24.1 | 18.1 | .35 NS |

| Allogeneic-matched sib | 27.6 | 26.8 | 22.8 | 25.7 | |

| Allogeneic-other | 62.1 | 51.8 | 52.6 | 56.1 | |

| Diagnostic group | |||||

| ALL | 27.1 | 26.8 | 26.3 | 26.9 | .98 NS |

| AML | 23.7 | 21.4 | 28.6 | 24.6 | |

| Other leukemia | 10.8 | 17.9 | 12.5 | 13.5 | |

| HD/NHL | 13.6 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 10.5 | |

| Solid tumor | 12.2 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 12.3 | |

| Nonmalignancy | 12.2 | 12.5 | 10.7 | 11.1 |

ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; AML, acute myelogenous leukemia; CHOP, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; HD, Hodgkin disease; HPI, health promotion intervention; HSC, Hospital for Sick Children; NCH, Nationwide Children’s Hospital; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; NS, not significant.

Hollingshead 4-factor index classes I–V.

Design and Procedure

Patients were recruited before admission for SCT. After informed consent and assent were obtained, each patient-parent dyad completed a battery of questionnaires before random assignment (stratified by age group, site, and type of transplantation) into 3 arms: child intervention, involving therapeutic massage and humor therapy (health-promotion intervention, child-focused); child-parent intervention, the child intervention plus a parent massage and relaxation/imagery intervention (health-promotion intervention, child and parent); or standard care (SC). The intervention began at admission and continued through SCT week+3. Participants completed outcome measures at admission and 24 weeks after SCT. More detail about the procedures is available in the prior report.29

Intervention

Patients randomized to intervention met with a licensed massage therapist for a 0.5-hour massage 3 times per week from admission through week+3. The humor intervention included psychoeducation and access to humorous materials, supported by weekly visits from a research assistant (RA) therapist. The parent massage intervention was identical to the child’s. For the relaxation intervention, parents were taught breath awareness and muscle release, followed by guided imagery. They were given a relaxation CD, encouraged to practice these techniques daily, and met weekly with the RA therapist for booster sessions. Patients in the SC arm received no experimental interventions, but each site provided comprehensive supportive care, including aggressive pharmacologic management of symptoms, and multidisciplinary psychosocial support teams.

Procedures were monitored to ensure protocol compliance and consistency across sites. Massage therapists completed a checklist of their activities after each session, rating the participants’ attitudes toward massage, the length of the session, and reasons for any deviations in routine. The RA therapists completed similar checklists after each relaxation or humor session. All relaxation sessions were audiotaped. Random review and ratings of recordings indicated therapist adherence to the standardized relaxation script. Finally, parents completed weekly checklists documenting their and their child’s intervention adherence. The number of massage sessions completed was used as an indicator of intervention compliance. With an expected “dosage” of 12 massage sessions (3/week × 4 week), the mean number of massages for patients was 8.8 (SD = 3.1; median = 10), and for parents was 7.6 (SD = 3.2, median = 8). Overall, 75% of the planned interventions were completed. A variety of reasons were given for missed sessions, but most were passively refused or missed for logistical reasons.

Outcome Measures

Children’s Depression Inventory

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI)30 is a 27-item self-report measure assessing depressive symptomatology. Reliability and validity are well established. Test-retest reliabilities range from 0.38 to 0.82.30 In the current study, 24-week test-retest consistency was 0.69. Age- and gender-corrected standardized T scores are provided for the age range 7 to 17. For patients age 6 and 18 in the current study, T scores were calculated based on the 7- and 17-year-old norms respectively.

University of California, Los Angeles, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

The University of California, Los Angeles, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition31,32 (PTSDI) is a 22-item measure used to assess symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder/posttraumatic stress syndrome (PTSD/PTSS) in children who have experienced a traumatic event. Both child self-report and parent-proxy versions were used. In the current sample, 24-week test-retest consistency was 0.49 by child report and 0.57 by parent report.

Children’s Health Questionnaire (child form, 87 items/parent form, 98 items)

The Children’s Health Questionnaire (CHQ)33 measures HRQL for children, with separate child (87 items) and parent (98 items) versions. We used 3 subscales from the Physical Domain (Physical Functioning, Pain, General Health) and 3 from the Psychosocial Domain (Mental Health, Behavior, Self-Esteem). All parent-child correlations on this instrument were significant and ranged from 0.33 on Behavior to 0.66 on Pain at Time 1, and from 0.39 on Behavior to 0.75 on General Health at Time 2.

Benefit Finding Scale for Children

The Benefit Finding Scale for Children (BFSC)28,34 includes 10 items that measure the appraisal of positive outcomes following an adverse event, such as serious illness. Higher scores reflect more benefit finding. Test-retest consistency at week+24 was 0.65.

Statistical Analysis

A mixed between-within subjects analysis of variance was conducted to evaluate the efficacy of the 2 intervention conditions on measures of adjustment and HRQL across admission and week+24 of SCT. In addition, we calculated the number of patients exceeding clinical cutoffs on the CDI and PTSDI, and compared scores to available normative data.

RESULTS

Depression

Across all participants, there was a significant change over time (F = 20.8, P < .001), indicating a reduction in scores from admission to week+24. There were no differences between groups (F = 0.3, P > .7), and no intervention effect, as the group by time interaction was not significant (F = 2.3, P > .10) (Fig 1A). The overall level of depressive symptoms was low, with CDI scores of the sample at admission (mean = 7.9, T score = 46.5) significantly below the norm for healthy children30 (t = −4.7, P < .001). At week+24, depression scores (mean = 5.8, T = 44.0) declined even further below normative values. At admission, 5.3% of children had CDI scores in the clinical range (T score ≥ 65); at week+24, 4.7% were in the clinical range; 9.6% of children in normative samples are expected to fall in this range.30

FIGURE 1.

Changes in symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress from admission to week+24 in relation to normative values (in green). A, CDI scores by child report. B, PTSDI scores by child report. C, PTSDI by parent report. HPI-C, child-targeted intervention; HPI-CP, child and parent-targeted intervention.

Posttraumatic Stress

PTSS declined significantly from admission to week+24 (F = 21.3, P < .001). There was no difference between groups (F = 0.9, P > .3), and no intervention effect (F = 0.8, P > .4) (Fig 1B). Similar findings were seen in parent-reported child PTSS, with a significant effect for time (F = 12.3, P < .001), but no group differences (P > .5) or intervention effect (P > .8). At admission, PTSS was greater than historical data of healthy peers35 by child report (t = 5.3, P < .01), but not parent report. By week+24, however, both patient- and parent-reported PTSS were no longer different from those of healthy children (Fig 1). Using the recommended cutoff score of 38 for identifying likely cases of PTSD,32 21.0% of patients exceeded this criterion by child report at admission, but at week+24, this had declined to 7.1%. By parent report, 14.5% exceeded the clinical cutoff at admission, but this declined to 6.2% at week+24.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Across participants, there was improvement on all subscales of the CHQ–child form87 (all P’s < .05, except physical functioning, P = .08). There were no differences between intervention groups (all P’s > .1), and no intervention effects (all P’s > .2) (Table 2). There was a similar improvement over time for parent-reported subscales on the CHQ–parent form98 (all P’s < .01, Table 2). Again, there were no significant group differences, nor group by time interactions (all P’s > .2). These outcomes are illustrated in Fig 2 for the CHQ subscales of Mental Health and Pain.

TABLE 2.

Means and SDs for Child- and Parent-Reported Outcomes at Week −1 and Week+24 Across Intervention Arm

| HPI-Child | HPI-Child-Parent | Standard Care | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week −1 | Week+24 | Week −1 | Week+24 | Week −1 | Week+24 | Week −1 | Week+24 | |

| Child-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| CDI | 8.5 (5.6) | 5.1 (3.9) | 7.9 (7.4) | 6.9 (7.6) | 7.5 (6.2) | 4.8 (5.1) | 7.9 (6.5) | 5.8 (5.9) |

| UCLA- PTSD I | 22.6 (14.8) | 17.9 (12.7) | 27.8 (15.5) | 19.6 (14.2) | 24.1 (13.9) | 14.8 (11.2) | 24.9 (14.9) | 17.7 (12.9) |

| BFS-C | 36.9 (7.5) | 39.8 (6.7) | 36.1 (8.5) | 39.9 (7.3) | 38.8 (8.6) | 42.1 (7.7) | 37.1 (8.2) | 40.6 (7.2) |

| CHQ-Physical Functioning | 72.8 (21.7) | 80.6 (19.7) | 76.4 (17.9) | 73.6 (22.4) | 77.4 (22.3) | 87.3 (13.5) | 75.5 (20.3) | 79.5 (20.1) |

| CHQ-Bodily Pain | 64.5 (29.8) | 76.9 (30.0) | 72.9 (23.4) | 78.8 (23.3) | 68.0 (31.9) | 83.5 (22.8) | 68.8 (27.8) | 79.3 (25.6) |

| CHQ-Behavior | 79.2 (9.2) | 81.9 (8.9) | 80.4 (10.1) | 84.5 (10.9) | 79.9 (17.8) | 86.8 (9.8) | 79.9 (12.1) | 84.2 (10.0) |

| CHQ-Mental Health | 71.6 (14.3) | 78.6 (13.8) | 69.1 (20.8) | 76.4 (18.0) | 74.9 (18.5) | 80.5 (15.8) | 71.4 (18.2) | 78.2 (16.0) |

| CHQ-General Health | 50.9 (19.3) | 58.7 (19.6) | 52.7 (15.2) | 56.3 (17.3) | 59.4 (21.22) | 62.2 (17.17) | 53.8 (18.39) | 58.7 18.0) |

| CHQ-Self-Esteem | 72.5 (16.1) | 82.8 (12.6) | 71.6 (18.7) | 79.7 (18.3) | 83.4 (17.7) | 84.3 (17.9) | 74.9 (18.1) | 81.9 (16.4) |

| Parent-reported outcomes | ||||||||

| UCLA-PTSD I | 19.2 (12.2) | 14.2 (12.6) | 21.8 (13.2) | 16.4 (14.1) | 17.1 (9.56) | 13.7 (16.1) | 19.7 (12.1) | 15.0 (13.9) |

| CHQ-Physical Functioning | 62.9 (25.4) | 78.9 (19.4) | 61.8 (25.1) | 67.2 (28.1) | 72.4 (27.2) | 76.4 (27.6) | 64.6 (25.8) | 73.5 (25.5) |

| CHQ-Bodily Pain | 60.2 (25.8) | 78.72 (21.3) | 68.9 (24.2) | 78.71 (22.9) | 65.7 (25.7) | 82.27 (20.1) | 65.1 (25.2) | 79.5 (21.6) |

| CHQ-Behavior | 81.8 (9.5) | 84.0 (9.2) | 80.9 (12.8) | 84.4 (13.0) | 81.6 (12.8) | 85.4 (11.5) | 81.4 (11.6) | 84.5 (11.3) |

| CHQ-Mental Health | 71.9 (14.6) | 80.1 (14.1) | 70.7 (16.0) | 79.2 (16.9) | 72.1 (15.7) | 81.7 (14.0) | 71.5 (15.3) | 80.1 (15.2) |

| CHQ-General Health | 43.8 (17.8) | 49.3 (14.2) | 45.8 (15.2) | 50.4 (15.74) | 50.8 (19.5) | 55.3 (17.1) | 46.3 (17.2) | 51.1 (15.6) |

| CHQ-Self-Esteem | 70.9 (18.4) | 79.8 (16.1) | 71.9 (18.5) | 75.9 (21.9) | 75.4 (18.2) | 80.2 (19.2) | 72.4 (18.31) | 78.3 (19.3) |

HPI, health promotion intervention.

FIGURE 2.

Child- and parent-reported pain and mental health at admission and SCT week+24 by intervention arm. A, CHQ-CF87 Mental Health scores by child report (normative values for healthy populations in green). B, CHQ-PF98 Mental Health, parent report. C, CHQ-CF87 Bodily Pain scores by child report. D, CHQ-PF98 Bodily Pain, parent report. HPI-C, child-targeted intervention; HPI-CP, child and parent-targeted intervention.

At admission, patient-reported CHQ scores across the sample were significantly poorer than norms for healthy children33,36 on the subscales of Physical Functioning (t = −8.3, P < .001) and General Health (t = −7.3, P < .001). Participants’ scores for Mental Health, Self Esteem, Behavior, and Bodily Pain were not statistically different from normative data (all P’s > .1).36 At week+24, patient scores on the subscales of Self Esteem (t = 4.1, P < .001), Behavior (t = 6.2, P < .001), Mental Health (t = 2.3, P = .02), and Bodily Pain (t = 2.6, P = .01) were significantly better than the norms for healthy children. Although the General Health and Physical Functioning subscale scores improved at week+24, patients’ scores remained below the norms for healthy children (P’s < .01). Parent reports of their child’s HRQL mirrored that of child report; however, comparable normative data are not available for the CHQ-parent form98.

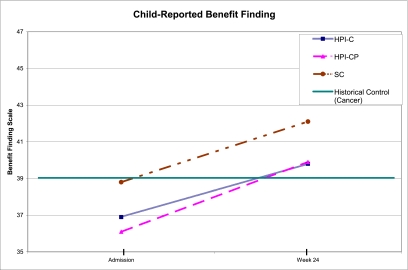

Benefit Finding

Similar to all other outcomes, improvement over time was observed on patient-reported benefit finding (F = 16.4, P < .001). Again, there were no significant differences between intervention arms (F = 1.0, P > .3), and no interaction (F = 0.14, P > .8) (Fig 3). The BFSC scores at admission were comparable to cross-sectional populations of children with cancer examined in earlier research (t = 1.1, P > .2), whereas at week+24, the BFSC scores (t = 4.8, P < .001) were significantly higher than those observed previously in childhood cancer populations.28,34

FIGURE 3.

Child-reported benefit finding scores at admission and SCT week+24 by intervention arm. Green line represents previously reported means for cross-sectional populations of children with cancer. HPI-C, child-targeted intervention; HPI-CP, child- and parent-targeted intervention.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter trial evaluating the impact of complementary therapies on distress in children undergoing SCT. Successful completion of the trial demonstrates the feasibility of introducing complementary therapies in the transplant setting; however, our results indicated no significant intervention effects on the adjustment and quality of life of children following SCT. This is consistent with the previously reported findings from this same trial regarding acute distress during the in-patient transplantation period.29 The lack of significant results can be better appreciated in the context of 2 findings that may be more noteworthy than the null intervention effects. First is the significant improvement over time on all outcomes across all patient groups, including those receiving only SC. Despite the aversive nature of SCT, patients reported feeling and functioning significantly better within 6 months of the procedure, and this was confirmed by parental report. Second is the good psychological adjustment levels observed at admission for SCT, which then continued to improve after transplantation. Such excellent adjustment has been reported previously in general pediatric oncology populations,3–6 but children undergoing SCT were thought to be a subgroup at higher risk of adjustment difficulties.10

The surprisingly positive adjustment of this multisite sample and the possible influence of low distress on the null intervention findings are illustrated in the outcome of depressive symptoms on the CDI. Even at the time of admission, the overall mean of the sample was below the normative mean of healthy children.30 This was followed by a significant decline in symptom scores at 6 months. The mean of the SC group, 4.8 at 6 months, is nearly an SD below normative expectations. It would have been difficult for any intervention to improve on this outcome.

In contrast, symptoms of posttraumatic stress at admission were elevated relative to published reports of healthy youth on the PTSDI instrument35, however, at 6 months after transplantation, PTSS scores were comparable with those of healthy youth. This finding suggests that most patients do not experience the procedure as a traumatic event, something that has been suggested in the pediatric transplant setting,37 and widely addressed as an outcome in adult SCT populations.38,39 Given that the normative response to SCT is recovery after a brief disruption, it appears that a resilience model, rather than a posttraumatic stress model, is a better fit for conceptualizing child response to SCT.

Patients and parents also reported reasonably good levels of the patient’s HRQL, as measured by subscales on the CHQ. Across groups, both sources reported scores within normal limits and comparable with healthy children on measures of pain, mental health, self-esteem, and behavior at admission, which then showed significant improvement at week+24. Measures of physical functioning and general health at admission were understandably lower than those obtained from healthy children. These showed significant improvement at week+24, but remained below normative levels. The improvement in physical and emotional functioning by 6 months is consistent with previously reported quality-of-life outcomes in pediatric SCT.40

The observed pattern of good adjustment and low distress during SCT is counterintuitive and contradictory to prior research, warranting further investigation about the factors that may contribute to these findings. Perhaps the most proximal explanation points to improvements in SC and the comprehensive supportive care practices in most pediatric SCT settings. In addition to close medical surveillance and aggressive pharmacologic symptom management, all sites maintain multidisciplinary psychosocial support teams (eg, child life, social work) who are available to patients throughout the process. This is not to suggest that the physical and psychological challenges of SCT have been eliminated, but that it may not be the ordeal that it once was, and does not appear to be traumatic for most patients, given current levels of supportive care.

Benefit finding and growth are also processes by which people may experience positive outcomes after a seemingly adverse event.26 This concept has been applied to the experience of serious illness and posited to play a role in adaptive functioning within both adult and pediatric cancer populations.26,28,41,42 Research has generally found a weak relationship between benefit finding and concurrent psychological distress, but it is predictive of adjustment over time.26,41 The current findings suggest that the pediatric SCT population may be particularly inclined to engage in a process of finding good in their experience and, as a result, cope better with the stressors of their treatment. Regardless of the explanation, pediatric SCT provides another example of human thriving in adversity, where resilience is the rule, and maladjustment is a relatively rare exception. It is possible that the positive outcomes observed are not unique to the SCT setting, but may be applicable to other life challenges, both medical and nonmedical,23–25 and perhaps are more readily observed in child than adult populations.

There are several potential study limitations. The high rate of attrition because of mortality, morbidity, and withdrawal (40%) reduced the evaluable sample size, resulting in adequate power to detect only moderate to large between-group differences. The lack of differences at baseline between those who completed the study and those who did not, assuages somewhat the concern about attrition and missing data. The wide age range of participants is another potential limitation, necessitating outcome assessment broadly across developmental levels. It is also possible that the intervention produced other benefits for patients and their families that we failed to measure. In this regard, collecting parallel qualitative data may have been useful. Although the multisite nature of the study adds to the generalizability of the findings, the participating sites may be somewhat atypical in the level of supportive care they provide, and may not be representative of all pediatric transplant centers. Despite these concerns, the results of this multisite trial suggest that children undergoing SCT are adjusting surprisingly well, and that with current levels of supportive care, SCT need not involve significant trauma, lingering distress, or disruptions in normal adjustment trajectories. These surprising findings require replication in future studies, but at present, appear to point to a remarkable resilience among the children who undergo this procedure.

Glossary

- BFSC

Benefit Finding Scale for Children

- CDI

Children’s Depression Inventory

- CHQ

Children’s Health Questionnaire

- HRQL

health-related quality of life

- PTSD

posttraumatic stress disorder

- PTSDI

University of California, Los Angeles, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

- RA

research assistant

- PTSS

posttraumatic stress syndrome

- SC

standard care

- SCT

stem cell transplantation

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 CA60616 and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

References

- 1.Patenaude AF, Kupst MJ. Psychosocial functioning in pediatric cancer. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(1):9–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aldridge AA, Roesch SC. Coping and adjustment in children with cancer: a meta-analytic study. J Behav Med. 2007;30(2):115–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noll RB, Gartstein MA, Vannatta K, Correll J, Bukowski WM, Davies WH. Social, emotional, and behavioral functioning of children with cancer. Pediatrics. 1999;103(1):71–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noll RB, Kupst MJ. Commentary: the psychological impact of pediatric cancer hardiness, the exception or the rule? J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1089–1098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dejong M, Fombonne E. Depression in paediatric cancer: an overview. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):553–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phipps S. Adaptive style in children with cancer: implications for a positive psychology approach. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1055–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M, Baghurst P. Childhood cancer: a 4-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22(3):214–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steele RG, Dreyer ML, Phipps S. Patterns of maternal distress among children with cancer and their association with child emotional and somatic distress. J Pediatr Psychol. 2004;29(7):507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazak AE, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA, Pai A, Reilly AF, Meadows AT. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: a blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1099–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Packman W, Weber S, Wallace J, Bugescu N. Psychological effects of hematopoietic SCT on pediatric patients, siblings and parents: a review. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2010;45(7):1134–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrera M, Atenafu E, Hancock K. Longitudinal health-related quality of life outcomes and related factors after pediatric SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44(4):249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phipps S. Psychosocial and behavioral issues in stem cell transplantation. In: Brown RT, ed. Comprehensive Handbook of Childhood Cancer and Sickle Cell Disease: A Biopsychosocial Approach. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006:75–99 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Garvie PA, Lensing S, Rai SN. Acute health-related quality of life in children undergoing stem cell transplant: I. Descriptive outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(5):425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Lensing S, Rai SN. Acute health-related quality of life in children undergoing stem cell transplant: II. Medical and demographic determinants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(5):435–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Streisand R, Rodrigue JR, Houck C, Graham-Pole J, Berlant N. Brief report: parents of children undergoing bone marrow transplantation: documenting stress and piloting a psychological intervention program. J Pediatr Psychol. 2000;25(5):331–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayer DK, Ratichek S, Berhe H, et al. Development of a health-related website for parents of children receiving hematopoietic stem cell transplant: HSCT-CHESS. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4(1):67–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Syrjala KL, Donaldson GW, Davis MW, Kippes ME, Carr JE. Relaxation and imagery and cognitive-behavioral training reduce pain during cancer treatment: a controlled clinical trial. Pain. 1995;63(2):189–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahles TA, Tope DM, Pinkson B, et al. Massage therapy for patients undergoing autologous bone marrow transplantation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999;18(3):157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith MC, Reeder F, Daniel L, Baramee J, Hagman J. Outcomes of touch therapies during bone marrow transplant. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(1):40–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cassileth BR, Vickers AJ, Magill LA. Music therapy for mood disturbance during hospitalization for autologous stem cell transplantation: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2003;98(12):2723–2729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(6):1143–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Penedo FJ, Molton I, Dahn JR, et al. A randomized clinical trial of group-based cognitive-behavioral stress management in localized prostate cancer: development of stress management skills improves quality of life and benefit finding. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(3):261–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonanno GA, Mancini AD. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):369–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masten AS. Ordinary magic. Resilience processes in development. Am Psychol. 2001;56(3):227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonnnano GA. Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2005;14(3):135–138 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park CL, Helgeson VS. Growth following highly stressful events: current status and future directions. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(5):791–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phipps S. Contexts and challenges in pediatric psychosocial oncology: chasing moving targets and embracing ‘good news’ outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(1):41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Currier JM, Hermes S, Phipps S. Brief report: Children’s response to serious illness: perceptions of benefit and burden in a pediatric cancer population. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(10):1129–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Phipps S, Barrera M, Vannatta K, Xiong X, Doyle JJ, Alderfer MA. Complementary therapies for children undergoing stem cell transplantation: report of a multisite trial. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3924–3933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pynoos R, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, Stuber M, Frederick C. UCLA PTSD Index for DSMIV, unpublished manual. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Trauma Psychiatry Service; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Decker KB, Pynoos RS. The University of California at Los Angeles post-traumatic stress disorder reaction index. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6(2):96–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landgraf J, Abetz L, Ware J. Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ): A User Manual. 2nd ed. Boston, MA: HealthAct; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phipps S, Long AM, Ogden J. Benefit Finding Scale for Children: preliminary findings from a childhood cancer population. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(10):1264–1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phipps S, Jurbergs N, Long A. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress in children with cancer: does personality trump health status? Psychooncology. 2009;18(9):992–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waters EB, Salmon LA, Wake M, Wright M, Hesketh KD. The health and well-being of adolescents: a school-based population study of the self-report Child Health Questionnaire. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29(2):140–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stuber ML, Nader KO, Houskamp BM, Pynoos RS. Appraisal of life threat and acute trauma responses in pediatric bone marrow transplant patients. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(4):673–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosher CE, Redd WH, Rini CM, Burkhalter JE, DuHamel KN. Physical, psychological, and social sequelae following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2009;18(2):113–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DuHamel KN, Mosher CE, Winkel G, et al. Randomized clinical trial of telephone-administered cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce post-traumatic stress disorder and distress symptoms after hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(23):3754–3761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Duhamel KN, et al. Maternal perspectives on children’s health-related quality of life during the first year after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplant. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(10):1100–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carver CS, Antoni MH. Finding benefit in breast cancer during the year after diagnosis predicts better adjustment 5 to 8 years after diagnosis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(6):595–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barakat LP, Alderfer MA, Kazak AE. Posttraumatic growth in adolescent survivors of cancer and their mothers and fathers. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(4):413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]