Abstract

Urachal cancer is a rare form of bladder cancer that arises from the urachus, a vestigial musculofibrous band that extends from the dome of the bladder to the umbilicus. Urachal cancer often presents at an advanced stage and has a dismal prognosis. We present a case of a young woman with urachal cancer that recurred rapidly post-partial cystectomy. The patient was treated with up to 6 different chemotherapy regimens, including an oral antiangiogenic drug as part of a clinical trial. Our case illustrates the aggressive nature of this disease, the difficulty in accessing drugs for the treatment of rare cancers and the lack of late stage clinical trials to help guide therapeutic decisions.

Case report

A 35-year-old woman, who was previously well, presented with an 8-month history of abdominal pain, urinary tract infections and a 4-month history of gross hematuria and bloody discharge from the umbilicus. She underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan which showed a 6.2 × 6.0 × 4.0 cm mass at the dome of the bladder extending anteriorly with trans-serosal involvement and irregular luminal and serosal margins (Fig. 1a). A biopsy of the mass performed via cystoscopy confirmed urachal adenocarcinoma. She then underwent a partial cystectomy to remove the urachus, umbilicus and pelvic lymph nodes. Pathology showed a 6.0 × 5.3 cm mucin producing adenocarcinoma, composed of nests of signet ring cells (Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b). Though the margins were negative, the tumour involved the full thickness of the bladder wall, extended to the perivesical fat and serosal surfaces, showed lymphovascular invasion and involved one of four pelvic lymph nodes. There were also several satellite tumour nodules in the perivesical fat. A restaging magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed 6 weeks after the partial cystectomy showed a small enhancing mass in the bladder, but this could not be visualized on cystoscopy. A CT scan 6 weeks later confirmed local recurrence (Fig. 1b) and a total cystectomy was planned. However, at the time of cystectomy, there was extensive peritoneal seeding, and as a result a cystectomy was not performed and the patient was referred to medical oncology for further management.

Fig. 1a.

Initial diagnosis. Sagittal image from non-contrast computed tomography cystogram shows a soft tissue mass arising from the anterior bladder dome. The mass contains small, coarse calcifications (thick arrow) and is growing outside the expected confines of the bladder wall corresponding anatomically to the urachal remnant.

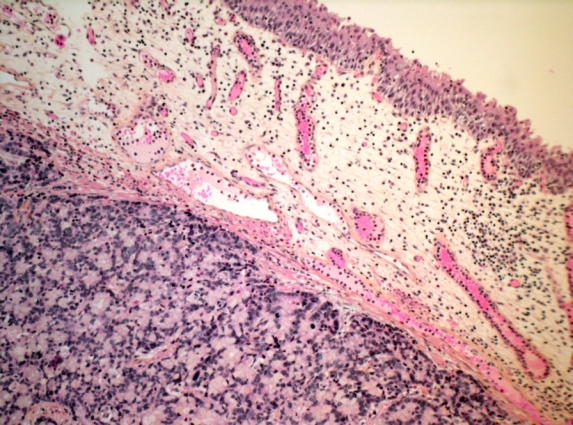

Fig. 2a.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification 2.5×. Urachal adenocarcinoma infiltrating lamina propria of urinary bladder with luminal non-tumorous urothelium.

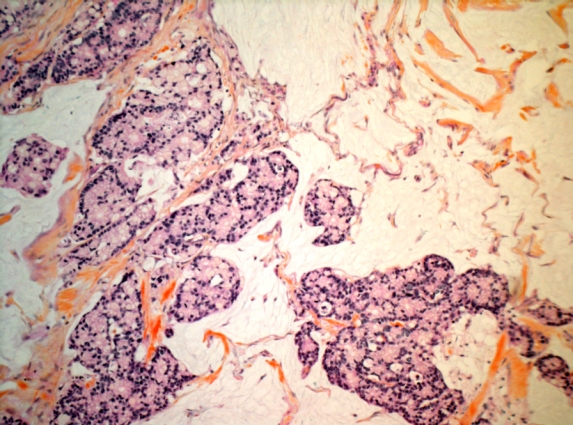

Fig. 2b.

Hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification 2.5×. Urachal mucinous adenocarcinoma, moderately differentiated with groups of tumour cells surrounded by extracellular mucin.

Fig. 1b.

Six weeks after partial cystectomy. Sagittal 5-minute delayed post-contrast T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging sequence with fat saturation shows small enhancing mass at the bladder dome.

Five months after her initial diagnosis, repeat staging scans showed widespread metastatic disease involving the lung and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (Fig. 1c, Fig. 1d). She began systemic treatment with a standard bladder cancer regimen consisting of gemcitabine and cisplatin. CT scans, performed after 3 cycles (3 months) of treatment, showed progressive retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy, so she was switched to second-line paclitaxel and carboplatin. This regimen was well-tolerated and CT scans done after 3 and 6 cycles showed stable disease, but scans after 9 cycles showed progression in both the lung and the peritoneum. She then received capecitabine and an oral antiangiogenic agent as part of a phase 1 trial. On this regimen, she had initial disease stabilization, but after 6 cycles had significant clinical and radiological progression with the appearance of large adnexal masses, malignant ascites and lesions in the urachal remnant and omentum. She also required bilateral nephrostomy tubes due to ureteric compression from her disease. She came off the trial and started on a single agent, irinotecan, intravenously every 3 weeks. Despite initial symptomatic benefit, further radiologic progression was seen after 3 cycles. She was then given a brief 6-week course of oral cylophosphamide+prednisone, but the disease progressed. She then had a cycle of capecitabine+oxaliplatin (XELOX), which became available on a compassionate basis, but unfortunately she died of further disease progression.

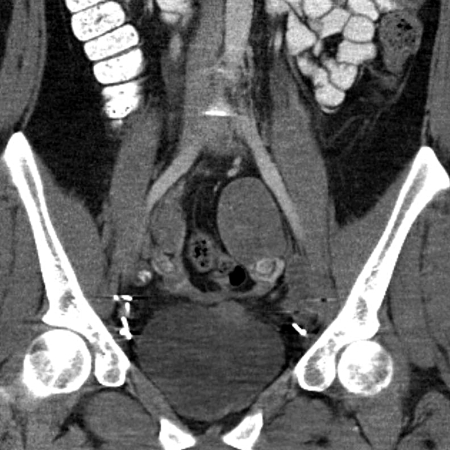

Fig. 1c.

Five months after partial cystectomy. Coronal reformatted intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan reveals a mass at the left anterior bladder dome containing calcifications, compatible with recurrent adenocarcinoma.

Fig. 1d.

Advanced disease. Coronal reformatted intravenous contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan shows left adnexal mass and part of right adnexal mass (thin arrows), metastatic right iliac lymph node with coarse calcification (arrowhead), and part of the left anterior bladder dome mass (thick arrow).

Discussion

Urachal cancers are rare and aggressive cancers of the bladder which were originally described by Hue and Jacquin in 1863. They account for only 0.5% of all bladder cancers, and 20% to 40% of primary bladder adenocarcinomas.1–3 To date, there have been no randomized trials and fewer than 300 cases reported in the literature. As a result, there is a paucity of information on how best to manage these cancers and specifically which chemotherapeutic agents are most effective in an atypical bladder cancer with histological and biological features similar to cancers of the bowel.

Urachal cancers arise from the urachus which is a vestigial embryonic structure located in the space of Retzius, between the transversalis fascia anteriorly and peritoneum posteriorly and between the dome of the bladder and the umbilicus.4,5 The urachus is composed of three layers: an outer muscular layer, middle connective tissue layer and an inner layer usually lined with transitional cell epithelium. Most urachal carcinomas are mucin-producing adenocarcinomas which exhibit signet ring cells and an enteric type histology more commonly seen in colon cancers.6 The MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) criteria helps in the diagnosis of urachal cancers (Table 1). These criteria include a midline location of the tumour; a sharp demarcation between the tumour and normal surface epithelium; an enteric histology; the absence of urothelial dysplasia, cystitis cystica or cystitis glandularis transitioning to the tumor; and the absence of a primary adenocarcinoma of another origin.7

Table 1.

The MD Anderson Cancer Center criteria for the diagnosis of urachal cancer

| Main criteria: |

| Location in the bladder dome or elsewhere in the midline of the bladder |

| Sharp demarcation between tumour and normal surface epithelium |

| Supportive criteria: |

| Enteric type histology |

| Absence of urothelial dysplasia |

| Absence of cystitis cystica or cystitis glandularis transitioning to tumour |

| Absence of primary adenocarcinoma of another origin |

Patients with urachal cancers often present with higher stage disease at diagnosis because the disease arises outside of the bladder where it does not cause any symptoms. Symptoms often occur only after the disease has progressed further and grown into the bladder secondarily. When symptoms occur they commonly include irritative voiding symptoms, discharge of mucous-like material and gross hematuria. Some patients also report umbilical pain and umbilical discharge.7 The standard workup includes CT or MRI evaluation of the abdomen and pelvis with a chest x-ray or preferably CT chest to rule out lung metastases. Cystoscopy and an exam under anesthesia are also recommended. As with other enteric malignancies, elevations in tumour markers, including carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA125 and cancer antigen 19-9, have been reported and in some cases a decrease in levels may correlate with response to systemic treatment.8–10 If a diagnosis of urachal cancer cannot be a made, a search for an alternate primary oncological diagnosis is recommended.

An en bloc resection of the urachal ligament and umbilicus is recommended for patients who have surgically resectable disease and either a complete or partial cystectomy ensuring negative margins. This is crucial because urachal tumours can occur anywhere along the urachus, including at the umbilicus (7%). If the urachus is transected during surgery, spillage of the tumour containing fluid into the peritoneal cavity can increase the risk of relapse.11,12 Currently, an open surgical approach is favoured due to the lack of long-term data on either laparascopic or robotic surgeries.13–15

Two systems have been proposed for staging urachal cancers. The first system was proposed by Sheldon and colleagues in 1984. In the Sheldon staging system, early stage urachal cancers are localized to the urachal mucosa, while late stage disease involves the local structures, such as the bladder, abdominal wall or peritoneum, and metastases to regional lymph nodes or distant sites. A more simplified system has been recently proposed by the Mayo clinic, though neither system has been validated (Table 2).11,16 The median survival for locally advanced or metastatic disease is between 12 and 24 months and the 5-year cancer specific survival rate for urachal cancers is only 50%.8,11

Table 2.

Staging systems for urachal cancers

| Stage | 1984: Sheldon et al12 | 2006: Ashley et al11 |

|---|---|---|

| I | Confined to urachal mucosa | Confined to urachus and bladder |

| II | Invasion confined to urachus | Extension beyond muscularis or urachus or bladder |

| III | – | Metastatic to regional lymph nodes |

| IIIA | Extension to bladder | – |

| IIIB | Extension to abdominal wall | – |

| IIIC | Extension to peritoneum | – |

| IIID | Extension to other viscera | – |

| IV | – | Metastatic to nonregional lymph nodes/distant sites |

| IVA | Metastatic to lymph nodes | – |

| IVB | Metastatic to distant sites |

Unlike other cancers, there is currently no standard adjuvant or metastatic chemotherapy regimen for the treatment of urachal cancers. The choice of regimens has been based largely on case reports and single institution experiences (Table 3). Chemotherapy regimens used and available in Canada to treat advanced bladder cancer, including gemcitabine+cisplatin or methotrexate+vinblastine+ doxorubicin+cisplatin (MVAC), have shown a few anecdotal responses in urachal cancers, but have generally yielded disappointing results.7,8,11 Given the enteric-type histology of urachal adenocarcinomas, chemotherapy regimens used to treat gastrointestinal malignancies may be more effective. Two case reports have described patients responding to irinotecan-based chemotherapy, a regimen commonly used to treat colorectal cancers.16,17 Two case reports using oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy have also shown benefit in urachal cancers.18,19 There is one report of a triplet combination of 5-flurouracil+doxorubicin+mitomycin-C showing activity in this disease.20 In terms of clinical trials, there was one trial of a triplet combination of ifosfamide+paclitaxel+cisplatin in advanced non-transitional cell carcinoma that has reported some activity in urachal cancers.21 There is also a phase II study evaluating gemcitabine+fluorouracil+leucovorin+cispl atin (GemFLP) in metastatic urachal cancer and other adenocarcinomas of the bladder, and preliminary results from this study are encouraging. With the lack of other effective options, this regimen has been adopted as the adjuvant and front-line metastatic regimen at the MDACC.7

Table 3.

Chemotherapy regimens tested in urachal cancers

| Regimen | N | Setting | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-1+cisplatin ×5 courses22 | 1 | Metastatic | 1 complete response, disease-free at 30 months |

| S-1+cisplatin23 | 1 | Metastatic | 1 response |

| FOLFOX418 | 1 | Perioperative | Minor response to chemotherapy, no recurrence after 1.5 years |

| Irinotecan24 | 1 | Metastatic | Partial response (tumour resistant to cisplatin, 5-FU, doxorubicin, epirubicin, mitomycin-C) |

| IFL16 | 1 | Metastatic | Complete response, recurrence after 6 months |

| Cisplatin+paclitaxel+ifosfamide21 | 6 | Advanced | 1 partial response, 4 with stable disease (duration of response not reported) |

| 5-FU+doxorubicin+VP16,doxorubicin+mitomycin-C+cisplatin | 1 | Metastatic | Both survived over 10 years, chemotherapy was given in the context of multimodality treatment |

| Doxorubicin+mitomycin-C+ cisplatin, uracil/ftorafur25 | 1 | Metastatic | |

| 5-FU+doxorubicin+mitomycin-C20 | 3 | Metastatic | 2 responses |

| Methotrexate+5-FU+epirubicin+cisplatin26,27 | 1 | Metastatic | Complete response |

| Ifosphamide+5-FU+VP16+cisplatin27 | 4 | Metastatic | 1 complete response, 2 partial response |

| Cisplatin+5-FU8 | 9 | Metastatic | 3/9 partial responses |

| MVAC8 | 5 | Metastatic | No response |

| Taxol+methotrexate+cisplatin8 | 1 | Metastatic | Response |

| Gem-FLP7 ongoing Phase II trial | Metastatic | 1 complete response, multiple partial responses |

S-1: oral fluoropyrimidine; FOLFOX4: oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 (D1), leucovorin 200 mg/m2 (D1,2), fluoruracil 400 mg/m2 (D1, D2), fluorouracil 600 mg/m2 CIV over 22 hours (D1,2); IFL: irinotecan 125 mg/m2, 5FU 500mg/m2, leucovorin 20mg/m2, once weekly for 4 to 6 weeks; MVAC: methotrexate, vinblastine, adriamycin, cisplatin; Gem-FLP: gemcitabine, 5FU, leucovorin, cisplatin.

In this case of advanced urachal cancer, taxanes and 5FU-based therapy may have slowed disease progression, similar to reports in larger case series with these agents. The response to taxanes is not surprising since taxanes have demonstrated efficacy in primary adenocarcinomas.21 Our patient responded favorably to capecitabine likely based on the enteric histology. She may have had some additional benefit from the antiangiogenic agent, but this would have to be tested in the context of a larger clinical trial. There was little response to either irinotecan or oxaliplatin, but this could easily have been attributed to the fact that she was already heavily pretreated by the time these agents became available on a compassionate basis. These agents, if available earlier, may have had more benefit. This raises an important issue regarding drug access and availability for patients with rare cancers. Often, there is no phase III clinical trial evidence and biological behaviour may differ from the site of origin necessitating the use of alternate treatment strategies. As we move towards a more personalized approach in oncology, treating according to the histology or other molecular features may improve outcomes in rare cancers such as this one.

Conclusion

Despite limited evidence, standard chemotherapy for patients with urachal adenocarcinoma should include a taxane or a regimen commonly used to treat gastrointestinal malignancies as opposed to standard transitional cell carcinoma regimens which have not shown much efficacy. The results of the phase II trial of gemcitabine+cisplatin+5-FU might further define a treatment standard for this disease. Ultimately, the inclusion of urachal cancer patients in clinical trials will be critical and may also be a mechanism to overcome drug access issues. Studies exploring the use of neoadjuvant, adjuvant or perhaps even intraperitoneal chemotherapy for urachal cancers may lead to better treatment strategies and ultimately better outcomes in this disease.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Munichor M, Szvalb S, Cohen H, et al. Mixed adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine carcinoma arising in the urachus. A case report and review of the literature. Eur Urol. 1995;28:345–7. doi: 10.1159/000475079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghazizadeh M, Yamamoto S, Kurokawa K. Clinical features of urachal carcinoma in Japan: review of 157 patients. Urol Res. 1983;5:235–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00272286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wright JL, Porter MP, Li CI, et al. Differences in survival among patients with urachal and nonurachal adenocarcinomas of the bladder. Cancer. 2006;4:721–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Upadhyay V, Kukkady A. Urachal remnants: an enigma. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:372–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-44725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scabini S, Rimini E, Romairone E, et al. Urachal tumour: case report of a poorly understood carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:82. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-7-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Gopalan A, Sharp DS, Fine SW, et al. Urachal carcinoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 24 cases with outcome correlation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:659–68. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31819aa4ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siefker-Radtke A. Urachal carcinoma: surgical and chemotherapeutic options. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2006;6:1715–21. doi: 10.1586/14737140.6.12.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siefker-Radtke AO, Gee J, Shen Y, et al. Multimodality management of urachal carcinoma: the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center experience. J Urol. 2003;169:1295–8. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000054646.49381.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kikuno N, Urakami S, Shigeno K, et al. Urachal carcinoma associated with increased carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen. J Urol. 2001;166:604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guarnaccia S, Pais V, Grous J, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the urachus associated with elevated levels of CA 125. J Urol. 1991;145:140–1. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38271-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashley RA, Inman BA, Sebo TJ, et al. Urachal carcinoma: clinicopathologic features and long-term outcomes of an aggressive malignancy. Cancer. 2006;107:712–20. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheldon CA, Clayman RV, Gonzalez R, et al. Malignant urachal lesions. J Urol. 1984;131:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milhoua PM, Knoll A, Bleustein CB, et al. Laparoscopic partial cystectomy for treatment of adenocarcinoma of the urachus. Urology. 2006;67:423.e15–17. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadhwa P, Kolla SB, Hemal AK. Laparoscopic en bloc partial cystectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy for urachal adenocarcinoma. Urology. 2006;67:837–43. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madeb R, Knopf JK, Nicholson C, et al. The use of robotically assisted surgery for treating urachal anomalies. BJU Int. 2006;98:838–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohile SG, Schleicher L, Petrylak DP. Treatment of metastatic urachal carcinoma in an elderly woman. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5:55–8. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tazi E, Lalya I, Tazi MF, et al. Treatment of metastatic urachal adenocarcinoma in a young woman: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:9145. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kikuchi M, Kamei S, Morirama Y, et al. Case of urachal cancer treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy with FOLFOX4 (oxaliplatin, 5-FU and leukovolin) [in Japanese] Hinyokika Kiyo. 2008;54:557–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tran B, McKendrick J. Metastatic urachal cancer responding to FOLFOX chemotherapy. Can J Urol. 2010;17:5120–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logothetis CJ, Samuels ML, Ogden S. Chemotherapy for adenocarcinomas of bladder and urachal origin: 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin-C. Urology. 1985;26:252–5. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90121-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galsky M, Iasonas A, Mironov S, et al. Prospective trial of ifosfamide, paclitaxel, and cisplatin (ITP) in patient with advanced non-transitional cell (non-TCC) carcinomas of the urothelial tract. Paper presented at: American Society of Clinical Oncology Annual Meeting; June 1–6, 2006; Fairfax, VA. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kojima Y, Yamada Y, Kamisawa H, et al. Complete response of a recurrent advanced urachal carcinoma treated by S-1/cisplatin combination chemotherapy. Int J Urol. 2006;13:1123–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sekita N, Fujimura M, Arai H, et al. A case of urachal carcinoma treated with S-1/CDDP combination chemotherapy [in Japanese] Hinyokika Kiyo. 2010;56:447–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kume H, Tomita K, Takahashi S, et al. Irinotecan as a new agent for urachal cancer. Urol Int. 2006;76:281–2. doi: 10.1159/000091635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kawakami S, Kageyama Y, Yonese J, et al. Successful treatment of metastatic adenocarcinoma of the urachus: report of 2 cases with more than 10-year survival. Urology. 2001;58:462. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(01)01259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hongoh S, Nomoto T, Kawakami M, et al. Complete response to M-FAP chemotherapy for multiple lung metastases after segmental resection of urachal carcinoma: a case report [in Japanese] Hinyokika Kiyo. 2010;56:107–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tatokoro M, Kawakami S, Yonese J, et al. Preliminary report of multimodal treatment with ifosfamide, 5-fluorouracil, etoposide and cisplatin (IFEP chemotherapy) against metastatic adenocarcinoma of the urachus. Int J Urol. 2008;9:851–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]