Abstract

The goal for this project was to examine the manner in which husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction was related to their perceptions of the availability of alternative partners and overall marital quality. Participants were 470 newlywed African Americans couples residing in the southern region of the United States. Path analysis was used to simultaneously examine actor (individuals’ sexual satisfaction on their own outcomes) and partner (individuals’ sexual satisfaction on their partners’ outcomes) effects. Wives’ and husbands’ sexual satisfaction was strongly positively associated with their own reports of marital quality, though it was not associated with their partners’ reports of marital quality. For both wives and husbands, higher sexual satisfaction was associated with lowered perceptions that they would be able to find other acceptable partners should their current relationship end. Perceived availability of alternative partners was, in turn, negatively associated with reports of marital quality.

Keywords: Sexual Satisfaction, Marriage, African American, Exchange Models

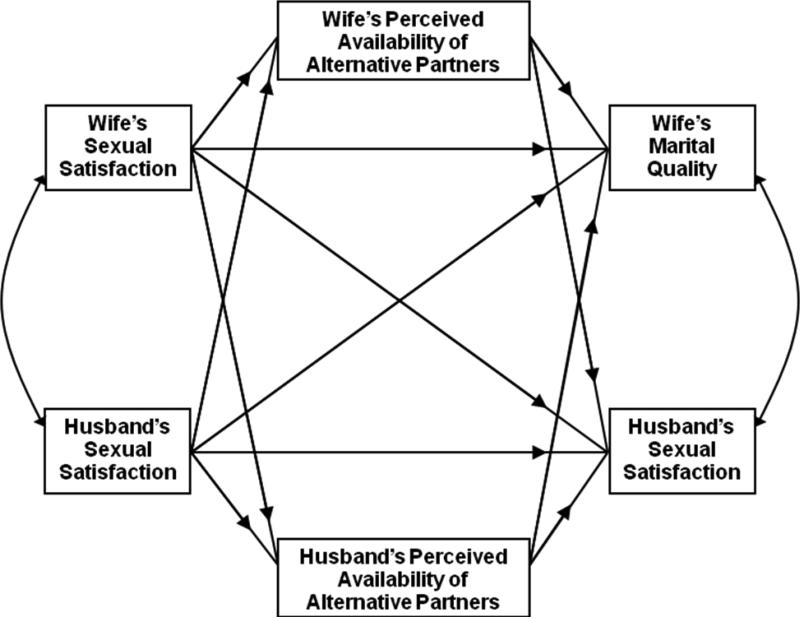

African American marriages are often plagued by discontent as evidenced by reports of poorer relationship quality, more frequent thoughts of divorce (Broman, 1993, 2005; Bulanda & Brown, 2007; Faulkner, Davey, & Davey, 2005), and higher rates of marital dissolution relative to couples of other races/ethnicities in the United States (Benokraitis, 2002; Bramlett & Mosher, 2002; Cherlin, 1998; Saluter, 1994; U.S. Census Bureau, 2009). While recent theoretical models (Bryant et al., 2010) have suggested a number of social, structural, and cultural factors that contribute to the marital instability experienced by African Americans, few empirical studies exist that examine marital processes in these couples. By exploring sexual satisfaction, which has been found to be robustly associated with overall marital satisfaction (for a review see: Sprecher & Cate, 2004), in a unique socio-demographically diverse sample of African American newlywed couples this research aims to begin filling that gap. Our conceptual model presented in Figure 1 and discussed in more detail in the following sections, employs an exchange framework and takes into account the interdependence inherent in dyadic data by incorporating elements of the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (Kenny, Kashy, & Cook, 2006). Specifically we aim to explore the manner in which African American spouses’ sexual satisfaction is related to their own and their partners’ marital quality both directly and indirectly through perceived availability of alternative partners.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the relationship between sexual satisfaction, perceived availability of alternative partners, and marital quality in newlywed African American couples.

Sexual Satisfaction and Marital Success

Since sexuality has gained a great deal of scientific focus during the last several decades, a large body of work has accumulated which provides evidence of a strong link between sexual satisfaction and overall relationship satisfaction (Blumstein & Schwarz, 1983; Henderson-King & Veroff, 1994; Sprecher & Cate, 2004). This association has been demonstrated in dating, cohabitating, married, and homosexual couples (Byers, 2005; Holmberg, Blair, & Phillips, 2010; Kurdek, 1991; Sprecher, 2002). Additionally, it has been found for couples in their mid-life who have been married for decades (Yeh at al., 2006) as well as those just beginning their marriages (Henderson-King, & Veroff, 1994). As Byers (1999) points out, however, the association between sexual and relationship satisfaction is stronger in the earlier years of marriage and diminishes somewhat as the relationship continues over time. Given the strong association between sexual satisfaction and relationship satisfaction it is unsurprising that sexual satisfaction also contributes to relationship stability (Dzara, 2010; Sprecher, 2002; Sprecher & Cate; Yeh, et al. 2006).

Though there is a clear link between sexual satisfaction and relationship outcomes, the direction of causality has been debated. It may be that enjoying a gratifying sexual relationship strengthens the overall relationship. However, as described by the Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction, it is also plausible that a solid relationship lays the groundwork for a satisfying sexual relationship (Lawrance & Byers, 1995). Studies that have sought to disentangle this issue have found that sexual and relationship satisfaction are intertwined and that changes in one accompany changes in the other in a bi-directional manner (Byers, 2005; Sprecher, 2002) . However, Yeh and colleagues (2006) using longitudinal data and cross-legged models, provide evidence that a causal series may exist, with sexual satisfaction preceding marital satisfaction. In the current work, although we favor this sequence, we are aware that feedback loops probably occur to some degree such that sexual satisfaction strengthens the relationship and relationship satisfaction promotes a satisfying sex life.

Sexual Satisfaction and Perceived Availability of Alternative Partners

To date, little attention has been paid to what, aside from relationship quality (e.g., Yeh et al., 2006), might facilitate the link between sexual satisfaction and relationship outcomes. Here, we seek insight into this process from a social exchange perspective, put forward by Byers and Wang (2004) as a potentially important area of investigation in sexual relationships. Theories of social exchange (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) suggest that people track the rewards and costs of their current relationship in two ways: First, they estimate what they believe they should receive from the relationship relative to what they put in, and second, they consider the quality and availability of alternative partners (Hatfield, Utne, & Traupmann, 1979; Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Rusbult, 1980). Empirical research has supported this by demonstrating that whether or not people choose to end a relationship is determined both by their dissatisfaction and their expectation that other potential partners are available to fulfill their needs (Drigotas & Rusbult, 1992; Rusbult, 1980; Rusbult, 1983). Additionally, it has been shown that when people are highly satisfied with a partner they tend to devalue alternative partners (Floyd & Wasner, 1994; Johnson & Rusbult, 1989; Simpson, Gangestad, & Lerma, 1990).

Having a sexually satisfying relationship with one's spouse is a reward of marriage, whereas being dissatisfied in this domain is a cost. Following from a social exchange perspective, we contend that being sexually satisfied in one's current relationship may be related to spouses’ perceptions of alternatives outside the relationship, such that higher satisfaction will be associated with lower expectations that other acceptable partners are available. Providing some support for this argument, Yabiku and Gager (2009) demonstrated that for both husbands and wives, feeling like their sex life would improve if they left the marriage significantly increased their risk of divorce. Further, dissatisfaction with the sexual aspect of marriage and the perception that other partners are available may result in individuals being more willing to engage in an extra-marital sexual relationship. In accordance with this Previti and Amato (2004) found that extra-marital sexual relationships result from marital discord and Liu (2000) demonstrated that sexual dissatisfaction in the marriage was often a precursor to infidelity. Detection that a partner has engaged in a sexual relationship without their spouse's consent often leads to the discontinuation of the relationship (Amato & Previti, 2003; Amato & Rogers, 1997).

Alternative Partners and Marriage among African Americans

Whether or not African American men and women believed they would be happier if their current marriages were to end had implications for the duration of their relationships (Trent & South, 2003). Interestingly though, the actual availability of alternative partners (measured by the ratio of men to women in the Labor Market Area in which the couples lived/worked) did not. The generally smaller pool of marriageable African American men relative to African American women (Cready & Fossett, 1997; Crowder & Tolnay, 2000; Licther, McLaughlin, Kephart, & Landry, 1992; Raley, 1996) has often been pointed to as a causal factor in the low rates of marriage and high rates of divorce among African Americans (Guttentag & Secord, 1983; Lawson & Thompson, 1999). Yet, data from Trent and South (2003) (as mentioned above) and from Rank and Davis (1996) imply that perceptions of available partners do not differ between African American men and women, and are in fact generally higher than those reported by men and women of other races and ethnicities. This suggests factors other than the relative number of men to women, influence people's perceptions of their likelihood of finding another acceptable partner should their current relationship end.

Current Study and Hypotheses

While a great deal of progress has been made on understanding the role of sexuality in marital relationships, several potentially important areas still need to be investigated. Given the lack of empirical focus on processes within African American married couples, sexuality within these couples has largely been ignored. Further, sexuality within married couples has also been relatively understudied (Christopher and Sprecher, 2000). Additionally, data on sexuality and sexual relationships have often been limited to reports from just one partner, which is not ideal considering the dyadic nature of sexual relationships (Stulhofer, Busko, & Brouillard, 2010). We seek to fill these gaps in the literature by examining dyadic data from a large socio-demographically diverse sample of African American couples in the early years of their marriages. Using the conceptual model illustrated in Figure 1 we test the following hypotheses: (1) sexual satisfaction will be directly related to marital quality such that the higher spouses’ sexual satisfaction, the higher their own and their partners’ reports of marital quality; and (2) sexual satisfaction will be indirectly related to marital quality through the perception of alternative partners such that the higher spouses’ sexual satisfaction the lower their expectations that acceptable alternative partners are available, which in turn will be related to marital quality.

Methods

Sample

Data for this study was gathered from 485 newlywed African American couples involved in a longitudinal study of African American marriage and health. Participants had originally been identified through marriage license applications from a state in the southern region of the United States that requested each partner indicate his or her race/ethnicity. Couples in which both partners self-identified as African American and were at least 20 years old were recruited via letter. Forty-seven percent of couples initially contacted elected to participate in the study. For the present analyses, we only used data from the second phase of the study during which measures of sexual satisfaction had been added to the survey.

Of the 485 couples who completed their second interviews, 470 were married, three were divorced, and twelve were separated. Data from couples who were divorced or separated were not included in any further analyses. Average age of wives was M(SD) = 34.72 (9.35) (range = 22-72) and average age of husbands was M(SD) = 37.64(10.71) (range = 23-80). Participants reported their earnings for the past year using income brackets representing $5,000 increments. Wives’ median income was $25,000 to $29,999 and husbands’ median income was $35,000 to $39,999. Almost a quarter (21.3%) of wives in the sample earned a high-school degree or less, 33.6% received some training beyond high-school, 31.9% earned a college degree, and 10.1% earned a graduate degree. Almost half (44.5%) of husbands in the sample earned a high-school degree or less, 32.8% received some training beyond high-school, 20% earned a college degree, and 2.5% earned a graduate degree. Average length of marriage was 2.03 years (SD=0.67).

Procedure

Beginning in 2007 and continuing through 2010, data were collected through home interviews. Trained interviewers visited each couple and after obtaining adult consent interviewed husbands and wives individually. Interviews lasted two hours, on average, and individuals received a monetary honorarium for participating in the study.

Measures

Sexual Satisfaction

Five items measured satisfaction with the sexual aspect of their marriage. Using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Agree...5 = Strongly Disagree) participants rated the following statements: I am sexually attracted to my spouse.(reverse scored in later analyses), The sexual aspect of our marriage needs to be improved., The sexual aspect of our marriage is in trouble., It is easy for me to talk to my husband/wife about sex. (Reverse scored), I am satisfied with how often my husband/wife and I have sex (make love). (Reverse scored), and I am satisfied with the quality of our sexual relations. (Reverse scored). Cronbach's alphas were .85 for wives and .83 for husbands.

Marital Quality

Marital quality was measured by combining six items that assessed partners’ satisfaction with and commitment to their marriage (Bryant, Conger, & Meehan, 2001; Glenn, 1990). Items included: All things considered, how happy are you with your marriage? (5 = very happy...1 = very unhappy), Since your wedding, how often have you ever thought getting married was not such a good idea? (1 = always...4 = never), How much do you want your relationship with your spouse to continue and succeed? (4 = desperately...1 = not at all), How hard are you willing to work to make your marriage succeed? (4 = I will go to any length...1 = I have given up), How likely is it that your marriage will last at least another five years? (5 = very likely...1 = very unlikely), and How likely is it that your marriage will last forever? (5 = very likely...1 = very unlikely). Cronbach's alphas were .84 for wives and .82 for husbands.

Perceived Availability of Alternative Partners

Participants’ perception of alternative partners was measured with the single item: How likely is it that you would be able to find another partner who would meet your standards if your marriage ended? Participants responded using a five-point scale (1 = very likely...5 =very unlikely) and their responses were reverse coded in further analyses for ease of interpretation.

Results

Means and standard deviations of all variables in the study are displayed in Table 1 separately for husbands and wives. Paired sample t-tests showed that wives were significantly younger, t(460) = 11.13, p <.001, earned less income, t(419) = -8.26, p <.001, were more educated, t(468) = 10.83, p <.001, perceived fewer alternative partners, t(460) = -2.18, p = .03, and reported lower marital quality compared to husbands, t(469) = -4.11, p = .002. Table 2 presents the correlations between all variables in our study. Age, education, and income were added as controls to all subsequent models and when significant were retained.

Table 1.

Mean (SD) of all variables reported by wives and husbands

| Wives | Husbands | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.72a (9.37) | 37.64b (10.73) |

| Income | 7.00a (2.87) | 8.34b (2.75) |

| Education | 5.29a (1.77) | 4.33b (1.66) |

| Sexual Satisfaction | 3.77(.81) | 3.75(.78) |

| Perceived Availability of Alternatives | 2.42a (1.38) | 2.60b (1.38) |

| Marital Quality | 3.97a (.61) | 4.08b (.50) |

Wives and husbands scores were compared using paired-sample t-tests.

Scores with different subscripts are significantly different, p <.05.

Scores with different subscripts are significantly different, p <.05.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations between all husbands’ and wives’ measures.

| Age Wife |

Age Husband |

Household Income |

Education Wife |

Education Husband |

Sexual Satisfaction Wife |

Sexual Satisfaction Husband |

Perceived Alternatives Wife |

Perceived Alternatives Husband |

Marital Quality Wife |

Marital Quality Husband |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Wife | 1 | ||||||||||

| Age Husband | 0.85*** | 1 | |||||||||

| Household Income | 0.14 | 0.05 | 1 | ||||||||

| Education Wife | -0.09 | -0.12* | 0.43*** | 1 | |||||||

| Education Husband | -0.13** | -0.16** | 0.38*** | 0.38*** | 1 | ||||||

| Sexual Satisfaction Wife | -0.01 | -0.08 | -0.08 | -0.06 | -0.04 | 1 | |||||

| Sexual Satisfaction Husband | 0.07 | 0.06 | -0.1* | -0.07 | -0.06 | 0.29** | 1 | ||||

| Perceived Alternatives Wife | -0.06 | -0.05 | 0.06 | 0.01 | -0.01 | -0.24** | -0.13** | 1 | |||

| Perceived Alternatives Husband | -0.07 | -0.07 | 0.01 | -0.07 | 0.05 | -0.1* | -0.2** | 0.2** | 1 | ||

| Marital Quality Wife | -0.01 | -0.03 | 0.06 | 0.09* | 0.14 | 0.46*** | 0.24*** | -0.32*** | -0.1* | 1 | |

| Marital Quality Husband | 0.01 | 0.002 | -0.02 | 0.16** | 0.06 | 0.2*** | 0.41*** | -0.24*** | -0.25*** | 0.45*** | 1 |

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Given that we had a more than adequate number of couples to employ path analysis, we randomly divided our sample into two groups (n = 235 couples). By creating two smaller sub-samples we were able to both test and replicate our model, providing a more stringent test of our hypotheses. A MANOVA revealed that the samples did not differ on any of the variables used in the study F(12, 390) = .61, p =.84. Stochastic regression imputation (Little & Rubin, 2002) was used to replace instances of missing data. This approach has been found to be superior compared to pair-wise deletion (Allison, 2002; Little, 1992).

Sample 1

Examining the fit indices, our a priori conceptual model fit our data well (Kline, 1998). The χ2 statistic (χ2 = 18.05, p .21) was not significant, the χ2/df (1.29) was well below the 3.0 maximum, GFI (.98) and CFI (.99) were well above the .90 threshold, and the RMSEA (.04) was well below the .08 threshold. A complete list of the path coefficients is presented in Table 3. Our first hypothesis was that there would be a positive relationship between individuals’ sexual satisfaction and both their own and their partners’ marital quality. In support of this hypothesis, the higher husbands’ sexual satisfaction the better their own and their wives’ reported marital quality. Wives’ reports of sexual satisfaction were also positively associated with their own reports of marital quality, but only marginally associated with their husbands’ reports of marital quality. Our second hypothesis was that in addition to the direct association between sexual satisfaction and marital quality, there would also be a mediated path through partners’ perceived availability of alternatives. Our data partially supported this; the higher wives’ rated their sexual satisfaction, the lower they rated their available alternatives. Although the relationship between husbands’ sexual satisfaction and perceived alternatives was negative, and thus in the expected direction, it was only marginally significant. In turn, for both husbands’ and wives’ availability of alternative partners was significantly negatively associated with marital quality. The variables in our model accounted for 24% and 22% of wives’ and husbands’ marital quality, respectively.

Table 3.

Sexual Satisfaction, Availability of Alternatives, and Marital Quality

| Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |||

| Wives’ Sexual Satisfaction | ||||||

| Marital Quality | W: | .22*** | .05 | W: | .39*** | .04 |

| H: | .07† | .04 | H: | .05 | .03 | |

| Availability of Alternatives | W: | -.39*** | .11 | W: | -.35** | .11 |

| Wives’ Availability of Alternatives | ||||||

| Marital Quality | W: | -.05* | .02 | W: | -.08*** | .02 |

| Husbands’ Sexual Satisfaction | ||||||

| Marital Quality | H: | .24*** | .04 | H: | .21*** | .04 |

| W: | .13** | .05 | W: | .05 | .05 | |

| Availability of Alternatives | H: | -.18† | .11 | H: | -.52*** | .11 |

| Husbands’ Availability of Alternatives | ||||||

| Marital Quality | H: | -.04* | .02 | H: | -.08*** | .02 |

| Husbands’ Education | ||||||

| Marital Quality | W: | .07*** | .02 | W: | .03† | .02 |

| Wives’ Education | ||||||

| Marital Quality | H: | .04** | .02 | H: | .04** | .01 |

| Husband's Age | ||||||

| Sexual Satisfaction | H: | .01* | .004 | |||

Note: All effects are reported as standardized regression coefficients (b). W = wife, H = husbands.

p<.10

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Sample 2

We sought to replicate our findings from the first test of our model, by fitting the model to the second randomly selected data sub-sample sample. In this case, the χ2 statistic (χ2 = 34.33, p = .02) was significant, warning us to interpret our model with caution. However, the other fit indicators suggested our model fit the data well. Again, the χ2/df (1.81) was below the 2.0, GFI (.97) and CFI (.94) were well above the .90 threshold, and the RMSEA (.06) was below the .08 threshold. Again, our first hypothesis was only partially supported. Although husbands’ sexual satisfaction was positively associated with their own reports of marital quality it was not significantly related to their wives’ reports of marital quality. Similarly, wives’ sexual satisfaction was associated with their own reports of marital quality, but only marginally associated with their husbands’ reports of marital quality. Here, we fully supported our second hypothesis; husbands’ and wives’ sexual satisfaction was negatively associated with their perceptions of the availability of alternatives which were in turn negatively related to marital quality.

Discussion

Utilizing a dual-informant approach from a sample of newlywed African American couples, the current work explored the association between sexual satisfaction and marital quality. As has been found in past research, our results suggest a strong positive association sexual satisfaction and overall relationship quality for husbands’ and wives’. Although, we expected individuals’ sexual satisfaction to be positively related to their partners’ marital quality, our data did not fully support this hypothesis. In our first sub-sample of data (n = 235 couples), husbands’ sexual satisfaction was positively associated with wives’ reports of marital quality, but the association between wives’ sexual satisfaction and husbands’ reports of marital quality were significant only at the trend level. In the second sample (n= 235 couples), these effects were not significant for husbands or wives, though they were in the expected direction. Consistent with our expectations, there was an indirect effect of sexual satisfaction and marital quality through perceived availability of alternatives. The more satisfied husbands and wives were, the less likely they thought they would be to find acceptable alternative partners, which was in turn negatively related to their reports of marital quality.

Implications

This research makes broad contributions to two aspects of sexuality research. First, it enhances our knowledge of sexual satisfaction in the context of the marital relationship. This is not only important for the scientific study of sexuality, but also because it produces further insight into what factors contribute to a healthy and enduring marriage. Doss, Simpson, and Christensen (2004) report that 28% of couples seeking marital therapy did so at least in part because of sexual discontentment. Satisfying and stable marriages can provide a buffer against many of life's persistent challenges (Holt-Lunstad, Birmingham, & Jones, 2008; Johnson, Backlund, Sorlie, & Loveless, 2000; Kiecolt-Glaser & Newton, 2001) and the inability to form and maintain stable unions has negative implications for physical and emotional well-being (Bryant & Conger, 2002; Simon & Marcussen, 1999). Given the strong relationship between sexual satisfaction and marital quality found here, it is essential that both researchers and practitioners continue to pay attention to the role of sexuality in marriage. This type of knowledge can be of considerable import to clinicians working to develop and implement interventions aimed at strengthening American families. Second, by using a dual-informant approach, our research also demonstrates the utility of gathering data from both members of a couple. Having research from both husbands and wives allowed us to control for the inter-correlation between husbands and wives sexual satisfaction to examine its effect on both perceptions of available alternatives and marital quality. Whenever possible, research in this area should aim to gather data from both members of a couple.

In addition to the broad implications of this work, it also makes two more specific contributions. By examining the relationship between sexual satisfaction and husbands’ and wives’ perceived availability of alternatives, this work provides additional support for the long-standing tradition of exchange models in relationship research and extends this to work on sexuality research (Sprecher, 1998). Additionally, and perhaps most importantly, this work illuminates a particularly understudied topic in social science research: the role of sexual satisfaction in African American relationships. Research on African American relationships often employs a race-comparative approach that while informative, may unintentionally negate the great deal of within race variation found among this group. When sexuality among African Americans is focused on it is often in the context of negative outcomes such as the transmission of HIV, teenage pregnancy, and non-marital childbearing (e.g. Bauermeister et al., 2009; East, 1998; Moore & Chase-Lansdale, 1991). Although this type of research is of great importance it may lead to viewing African American sexual relationships from a deficit perspective. By focusing only on African Americans in intact marital relationships this study provided some positive insights into African American marriage, namely that being sexually satisfied with ones partner had direct positive effects on marital quality and indirect positive effects that were mediated through a devaluing of alternatives outside the relationship.

Limitations and Future Directions

Though the research presented here has several strengths and makes both theoretical and practical contributions, there are a few limiting factors which must be considered when extending the findings and designing future studies. First, this study focused only on newlywed couples. These couples may still be in the “honeymoon phase” of their relationship and thus sexual satisfaction may be at its peak. Past research has suggested that although marital satisfaction may be less dependent on sexual satisfaction as relationships mature (Byers, 1999), couples are more likely to remain in relationships when initial reports of sexual satisfaction are high (Oggins, Leber, & Veroff, 1993; White & Keith, 1990). Therefore, a second consideration is that this study only uses self-reports of behaviors. It would be interesting to examine whether observed reports of actual decisions to stay or leave the marriage yield different results. Additionally, as past research has shown that sexual dissatisfaction is a precursor to individuals engaging in extra-marital sexual relationships (Liu, 2000; Previti and Amato, 2004) it would be informative to examine if availability of perceived partners measured at Time 1 was related to cheating on a spouse at a later point in time. Third, given the cross-sectional nature of this data causal inferences cannot be drawn. Fourth, although this study highlights the importance of sexual satisfaction in newlywed African American marriages, it does not seek to understand the correlates of sexual satisfaction in these relationships. Given that much of the work in this area has been done with White Americans, exploring the demographic and relationship factors that are associated with sexual satisfaction for African American couples would be informative. Finally, the present study relies on data gathered as part of a larger study examining multiple aspects of African American health and marriage, and thus, some items used to represent the constructs we wished to study are not ideal.

Conclusions

The research presented here was undertaken in an effort both to explore sexual satisfaction in the context of the marital relationship and to further elucidate the causes of marital discord within African American couples. Our results suggest that sexuality is an important component of African American marriage. Specifically, we demonstrated that sexual satisfaction contributes to husbands’ and wives’ perceptions that their likelihood of finding an acceptable alternative partner is poor, thereby strengthening their commitment to their current partner. Because of its centrality to marriage, therapeutic interventions aimed at improving the intimate aspects of couples’ relationships or pre-marital interventions designed to facilitate sexual communication and openness between partners may be a key component of combating high-rates of marital discontent and dissolution.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, R01-HD050045-05, Chalandra M. Bryant, Principal Investigator. We thank Susan McHale, Elizabeth Riina, Emily Doyle, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on earlier versions of this manuscript and the participating couples for their time and insights into romantic relationships.

Contributor Information

Christine E. Stanik, The Pennsylvania State University

Chalandra M. Bryant, The University of Georgia

References

- Allison PD. Missing Data. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA, Gee GC, Caldwell C, Xue Y. Work and sexual trajectories among African American youth. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46(4):290–300. doi: 10.1080/00224490802666241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein P, Schwartz P. American couples: Money, work, and sex. William Morrow; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Race differences in marital well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;5(3):724–732. [Google Scholar]

- Broman CL. Marital quality in Black and White marriages. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26:431–441. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Conger RD. An intergenerational model of romantic relationship development. In: Vangelsti AL, Reiss HT, Fitzpatrick MA, editors. Stability and change in relationships. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. p. 57082. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Conger RD, Meehan JM. The influence of in-laws on change in marital success. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:614–626. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Wickrama KAS, Bolland J, Bryant BM, Cutrona CE, Stanik CE. Race matters even in marriage: Identifying factors linked to marital outcomes for African Americans. Journal of Family Theory & Review. 2010;2:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda JR, Brown SL. Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research. 2007;36:945–967. [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES. The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction: Implications for sex therapy with couples. Canadian Journal of Counseling. 1999;33(2):113–118. [Google Scholar]

- The Interpersonal Exchange Model of Sexual Satisfaction: Implications for Sex Therapy with Couples. Source: Canadian Journal of Counselling [0828-3893] Byers. 1999;33(2):95. [Google Scholar]

- Byers ES. Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. The Journal of Sex Research. 2005;42(2):113–118. doi: 10.1080/00224490509552264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher FS, Sprecher S. Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal fo Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:999–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KH, Catania JA, Dolcini MM. Extramarital sex and HIV risk behavior among US adults: Results from the National AIDS Behavioral Survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1994;84(12):2003–2007. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.12.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook WL, Kenny DA. The actor-partner interdependence model: A model of bidirectional effects in developmental studies. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(2):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder KD, Tolnay SE. A new marriage squeeze for Black women: The role of racial intermarriage by Black men. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:792–807. [Google Scholar]

- Doss BD, Simpson LE, Christensen A. Why do couples seek marital therapy? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35(6):608–614. [Google Scholar]

- Drigotas SM, Rusbult CE. Should I stay or should I go? A dependence model of break-ups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;62(1):62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Dzara K. Assessing the effect of sexual satisfaction on marital disruption. Social Science Research. (In Press) [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Racial and ethnic differences in girls’ sexual, marital, and birth expectations. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1998;60(1):150–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner RA, Davey M, Davey A. Gender-related predictors of change in marital satisfaction and marital conflict. American Journal of Family Therapy. 2005;33:61–83. [Google Scholar]

- Glenn N. Quantitative research on marital quality in the 1980s: A critical review. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:818–831. [Google Scholar]

- Guttentag M, Secord PF. Too many women? The sex ratio question. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Utne MK, Traupmann J. Equity theory and intimate relationships. In: Burgess RL, Huston TL, editors. Social exchange in developing relationships. Academic Press; New York: 1979. pp. 99–133. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson-King DH, Veroff J. Sexual satisfaction and marital well-being in the first years of marriage. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1994;11:509–534. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Birmingham W, Jones BQ. Impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:239–244. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9018-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg D, Blair KL, Phillips M. Women's sexual satisfaction as a predictor of well-being in same-sex versus mixed-sex relationships. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(1):1–11. doi: 10.1080/00224490902898710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson NJ, Backlund E, Sorlie PD, Loveless CA. Marital status and mortality: the National Longitudinal Mortality Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 2000;10:224–238. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(99)00052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy DA, Kenny DA. The analysis of data from dyads and group. In: Reis HT, Judd CM, editors. Handbook of research methods in social psychology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley HH, Thibaut JE. Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, Cook WL. Dyadic Data Analysis. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127(4):472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Sexuality in homosexual and heterosexual couples. In: McKinney K, Sprecher S, editors. Sexuality in close relationships. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1991. pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrance K, Byers ES. Sexual satisfaction in long-term relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships. 1995;2:267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson EJ, Thompson A. Black men and divorce. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Kephart G, Landry DJ. Race and the retreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American Sociological Review. 1992;57:781–799. [Google Scholar]

- Little R. Regression with missing X's: A review. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1992;87:1227–1237. [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Wiley-Interscience, New York; 2002. (2002) [Google Scholar]

- Liu C. A theory of marital sexual life. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2000;62:363–374. [Google Scholar]

- McNulty JK, Fisher TD. Gender differences in response to sexual expectancies and changes in sexual frequency: A short-term longitudinal study of sexual satisfaction in newly married couples. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:229–240. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore MR, Chase-Lansdale PL. Sexual intercourse and pregnancy among African American girls in high-poverty neighborhoods: The role of family and perceived community environment. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1991;63(4):1146–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Morokoff PJ, Gillilland R. Stress, sexual functioning, and marital satisfaction. The Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30(1):43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Oggins J, Leber D, Veroff J. Race and gender differences in black and white newlyweds’ perceptions of sexual and marital relationships. The Journal of Sex Research. 1993;30:152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Previti D, Amato PR. Is infidelity a cause or a consequence of poor marital quality? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2004;21(2):217–230. [Google Scholar]

- Raley RK. A shortage of marriageable men? A note on the role of cohabitating in Black-White differences in marriage rates. American Sociological Review. 1996;61:973–983. [Google Scholar]

- Rank MR, Davis LE. Perceived happiness outside of marriage among Black and White spouses. Family Relations. 1996;45(4):435–441. [Google Scholar]

- Renne KS. Health and marital experience in an urban population. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1971;33(2):338–350. Decade Review, Part 3. [Google Scholar]

- Robles T. Close Relationships and Health: Studying the effects of marriage and relationship quality on health. UCLA Center for the Study of Women; UC Los Angeles: 2008. [March 17, 2010]. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3tr4j5n7. [Google Scholar]

- Robles TF, Kiecold-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: Pathways to health. Physiology & Behavior. 2003;79:409–416. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the investment model. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1980;16:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult CE. A longitudinal test of the investment model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;45(1):101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Simon RW, Marcussen K. Marital transitions, marital beliefs, and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:111–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Social exchange theories and sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research. 1998;35(1):32–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S. Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. The Journal of Sex Research. 2002;39(3):190–196. doi: 10.1080/00224490209552141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S, Cate RM. Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability. In: McKinney K, Sprecher S, editors. Sexuality in close relationships. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 2004. pp. 235–256. [Google Scholar]

- Stulhofer A, Busko V, Brouillard P. Development of bicultural validation of the new sexual satisfaction scale. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(4):257–268. doi: 10.1080/00224490903100561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz ME, Egley LC. Comparing one-partner and couple data on sensitive marital behaviors: The case of marital violence. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57(4):995–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM. Marital status and health. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1979;41(2):267–285. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron I, Hughes ME, Brooks TL. Marriage protection and marriage selection--Prospective evidence for reciprocal effects of marital status and health. Social Science & Medicine. 1996;43(1):113–123. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Klohnen EC, Casillas A, Nus Simms E, Haig J, Berry DS. Match makers and deal breakers: Analyses of assortative mating in newlywed couples. Journal of Personality. 2004;72:1029–1068. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Keith B. The effect of shift work on the quality and stability of marital relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;52:453–462. [Google Scholar]

- Yabiku ST, Gager CT. Sexual frequency and the stability of marital and cohabitating unions. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;7:983–1000. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh H-C, Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Elder GH. Relationships among sexual satisfaction, marital quality,and marital instability at midlife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:339–343. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.2.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]