Abstract

The Gi-coupled A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) mediates anti-inflammatory, anticancer and anti-ischemic protective effects. The receptor is overexpressed in inflammatory and cancer cells, while low expression is found in normal cells, rendering the A3AR as a potential therapeutic target. Highly selective A3AR agonists have been synthesized and molecular recognition in the binding site has been characterized. The present review summarizes preclinical and clinical human studies demonstrating that A3AR agonists induce specific anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects via a molecular mechanism that entails modulation of the Wnt and the NF-κB signal transduction pathways. Currently, A3AR agonists are being developed for the treatment of inflammatory diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis; ophthalmic diseases such as dry eye syndrome and glaucoma; liver diseases such as hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis.

Keywords: G protein-coupled receptor, nucleoside, cancer, inflammation, ischemia

I. Introduction

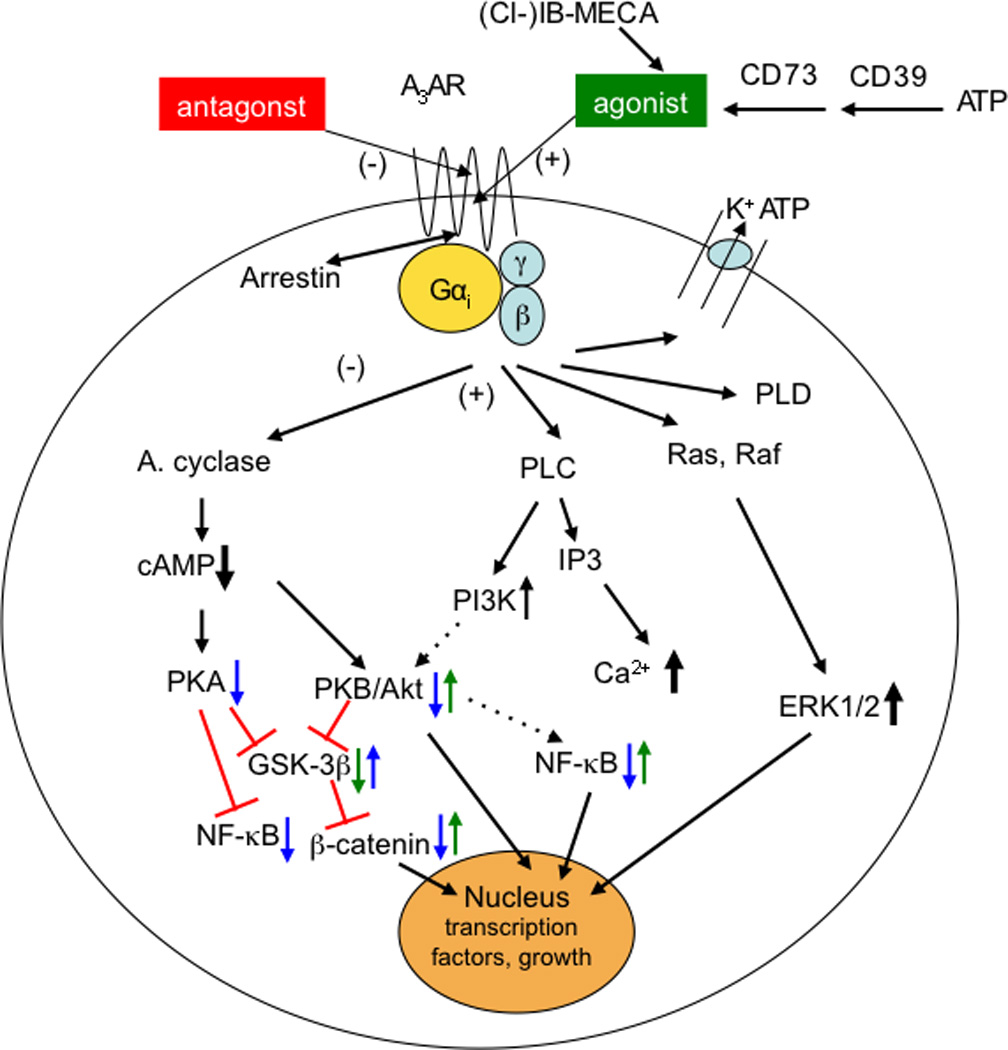

The A3AR is a subtype of the adenosine receptor (AR) family, which additionally includes the A1, A2A, and A2B receptors [1,2]; each is encoded by a separate gene and has different physiological roles. The Gi-coupled A3AR is less widely distributed than other AR subtypes with expression in humans in lung, liver, brain, aorta, testis and heart. The utilization of the A3AR as a therapeutic target and a biological predictive marker is based on two major findings: (a) A3AR is overexpressed in cancer and inflammatory cells, while low expression is found in normal cells [3–5]. The high receptor expression is also found in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with cancer or inflammatory diseases [5,6]. (b) Highly selective A3AR agonists have been synthesized and induce specific anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects via a molecular mechanism that entails modulation of the Wnt and the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) signal transduction pathways [6–8] (Figure 1). A protective effect of the agonists on normal cells was recorded as well, suggesting that this unique differential effect of the agonists will contribute to a safety profile of these drug candidates in both pre-clinical and clinical studies. Currently, A3AR agonists are being developed for the treatment of inflammatory, ophthalmic and liver diseases and demonstrate excellent safety and efficacy in Phase 2 clinical studies.

Figure 1.

Signaling pathways involved in the action of A3AR agonists. Pathways proposed to be involved in anticancer, antiinflammatory, and cardioprotective effects of A3AR agonists. A3AR signals through both G protein-dependent (via Gi or β,γ subunits) and independent pathways. Translocation of arrestin to the A3AR would be associated with receptor downregulation [22] and G protein-independent signaling. Not all pathways are present in all circumstances, and other pathways not shown can also affect cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. In cancer (blue arrows), activation of the A3AR corrects an imbalance in the downstream Wnt signaling pathway [6,34]. Administration of an A3 agonist to activate its cell surface receptor inhibits the formation of cAMP and indirectly decreases phosphorylation (and therefore decreased inactivation) of the serine/threonine kinase GSK-3β. The resulting increased phosphorylation of β-catenin causes it to be removed from the cytoplasm by ubiquitination and therefore preventing its nuclear import. This results in a net suppression of cyclin D1 and c-myc, which leads to cell growth inhibition. With respect to cancer, NF-κB is a potent anti-apoptotic agent in malignant cells and its activation is strongly associated with tumors [76]. Additionally, as a major cell survival signal, NF-κB is involved in multiple steps in carcinogenesis and in cancer cells‘ resistance to chemo- and radiotherapy. Thus, drugs aimed to decrease expression or activity of NF-κB could abrogate its anti-apoptotic effect. In inflammatory models [7,8,9,20,29,71], the reduced activation of NF-κB (in synoviocytes, neutrophils, and other immune cells) has an antiinflammatory effect, in part by reducing the expression of TNF-α. Opposite effects of A3AR activation on some of these pathways (green arrows) are associated with myeloprotective (via increased NF-κB in splenocytes [39]) and cardioprotective (GSK-3β inhibition [47]) responses to A3AR agonists. In the heart, there are opposing effects of GSK-3β at different stages of prolonged ischemia (GSK-3β protects) and reperfusion (GSK-3β inhibition protects) [77].

II. A3AR Agonists

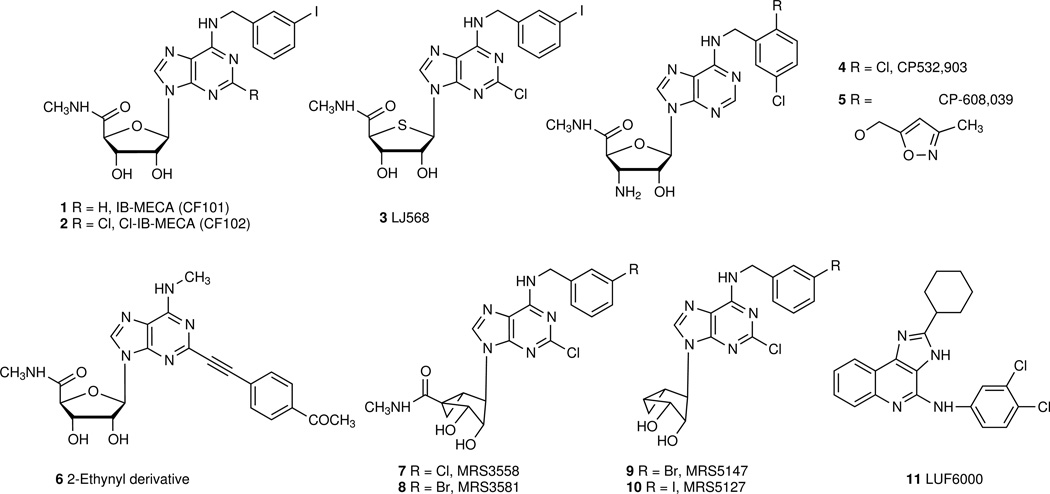

The human A3AR was cloned in 1993 [1] and soon thereafter found to have cerebroprotective and cardioprotective properties [9, 10]. Like other G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), it is also known to affect G protein-independent signaling, such as translocation of arrestins, leading to rapid desensitization of the A3AR in vitro (typically ~20 min in the presence of agonist) [11,12]. Highly selective A3AR agonists have been synthesized, and molecular recognition in the binding site has been characterized using site-directed mutagenesis and molecular modeling. Typical A3AR agonists are adenosine derivatives that contain 5‘-uronamide and N6-benzyl modifications leading to nanomolar receptor affinity (compounds numbered in bold as shown in Figure 2) [13]. The prototypical agonists IB-MECA 1 (N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5‘-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, CF101) and its 2-chloro analogue Cl-IB-MECA 2 (2-chloro-N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-5‘-N-methylcarboxamidoadenosine, CF102) are 9-ribosides with A3AR selectivity. Other selective A3 agonists include the 4‘-thio derivative 3, 3‘-amino-3‘-deoxy derivatives CP-608,039 5 ((2S,3S,4R,5R)-3-amino-5-{6-[5-chloro-2-(3-methylisoxazol-5-ylmethoxy)benzylamino]-purin-9-yl-l-4-hydroxytetrahydrofuran-2-carboxylic acid methylamide) and its dichlorobenzyl analogue CP-532,903 4, which were originally developed for cardioprotection, and the N6-methyl-2-ethynyl derivative 6 [9,14]. Introduction of a fused bicyclic ring in the rigid analogue MRS3558 7 ((1'R,2'R,3'S,4'R,5'S)-4-{2-chloro-6-[(3-chlorophenylmethyl)amino]purin-9-yl}-1-(methylaminocarbonyl)-bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2,3-diol) increased A3AR potency and selectivity, and identified the North conformation of the ribose ring as the preferred conformation in receptor binding. 7 also shows a preference in potency for the cAMP pathway, in comparsion to arrestin signaling [12]. Truncation of nucleosides at the 4‘-position reduces efficacy while retaining affinity of binding to the A3AR. Thus, the methanocarba analogues MRS5147 9 ((1‘R,2‘R,3‘S,4‘R,5‘S)-4‘-[2-chloro-6-(3-bromobenzylamino)-purine]-2‘,3‘-O-dihydroxybicyclo-[3.1.0]hexane) and its 3-iodo analogue MRS5127 10 are low efficacy partial A3AR agonists, that are selective in both human and rat [15]. Recently, macromolecular conjugates (e.g. polyamidoamine dendrimers) of chemically functionalized AR agonists were introduced as potent polyvalent activators of the receptors that are qualitatively different in pharmacological characteristics in comparison to the monomeric agonists [16]. Several A3AR PET ligands have been introduced for in vivo imaging: the antagonist [18F]FE@SUPPY (5-(2-fluoroethyl) 2,4-diethyl-3-(ethylsulfanylcarbonyl)-6-phenylpyridine-5-carboxylate [16], and a pair of nucleosides, e.g. low efficacy agonist [76Br]MRS5147 9 and full agonist [76Br]MRS3581 8.

Figure 2.

Representative agonists (1 – 8) and partial agonists (9, 10) of nanomolar affinity at the A3AR and a positive allosteric modulator 11. Nucleosides 7 – 10 contain the (North) methanocarba substitution of the ribose ring, which maintains an A3AR-preferred conformation.

The selectivity of A3AR agonists differs between in vitro and in vivo models and between species, although the sequence identity is high (84.4%) within the transmembrane region. The characterization of a given nucleoside derivative as full or partial agonist is highly dependent on the pharmacological system, such that 2 ranges from full agonist to low efficacy partial agonist [17]. LUF6000 11 (N-(3,4-dichloro-phenyl)-2-cyclohexyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine) is a selective positive allosteric modulator of the human A3AR [18], increasing the maximal effect of inhibition of adenylate cyclase. Species-dependence of the affinity and selectivity of A3AR antagonists should be carefully considered in preclinical studies. Functional polymorphism of A3AR is known; a high-transcript haplotype of the A3AR gene was associated with the development of cutaneous hyper-reactivity to aspirin [19].

III. Differential expression of A3AR in pathological and normal cells

A3AR was found to be over-expressed in various neoplastic cells including leukemia, lymphoma, astrocytoma, melanoma and pineal tumor cells, while low or almost no receptor expression was found in normal cells [20–25]. Similar data were reported in studies the receptor expression levels in tumor tissues derived from patients with colon, breast, small cell lung, pancreatic and hepatocellular carcinomas, and melanoma in direct comparison with adjacent normal tissues [3,4,6]. A direct correlation between A3AR expression levels and disease progression was described in breast and colon cancer [3,4].

A similar pattern of receptor over-expression was described in inflammatory cells both in experimental animal models and humans. The most studied inflammatory disease was rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in which A3AR over-expression was detected in paw tissue, draining lymph nodes and synovial cells of rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis and in synovial cells from patients with RA [7]. Similar data were observed in colon tissues derived from rats with colitis and in lungs upon inhalation of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) by mice [26,27]. The receptor was also highly expressed in anterior segment tissues derived from eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome in comparison to healthy subjects‘ eyes [28].

The high expression levels of A3AR seen in tumor and inflammatory cells were also found in PBMCs derived from tumor-bearing animals and cancer patients [3,6]. Similarly, high receptor expression levels were found in PBMCs derived from experimental animal models of inflammation and from patients with autoimmune inflammatory diseases, such rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn‘s disease [5,7,29].

These data suggest that A3AR expression levels in PBMCs mirror the receptor expression levels in the remote tumor or inflammatory tissue, rendering the receptor a biological marker. A3AR upregulation is attributed to factors including elevated adenosine and cytokines, which are characteristic of the microenvironment of cancer and inflammatory cells [29,30]. Under stressed metabolic conditions, extracellular adenosine of intracellular origin accumulates in the surroundings [30,31]. Upon binding to cell surface receptors, adenosine may induce, via an autocrine pathway, the expression of its own receptors. The pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), via binding to its cell surface receptor, initiates downstream signaling to result in upregulation of protein kinase B (PKB)/Akt, the inhibitor of nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells (IκB), IκB kinase (IKK) and the transcription factor NF-κB [24,28]. The latter is known to act as an A3AR transcription factor. Bioinformatic analyses revealed that besides NF-κB, other transcription factors such as c-Rel, MyoD, c-fos, GR, CREB, AP-1, GATA-1, C/EBP, c-Jun and PU.1 bind to the A3AR promoter region. It is well established that pro-inflammatory cytokines regulate the cell expression levels of each of these transcription factors, hence regulating A3AR expression levels [5]. Taken together, it seems that receptor overexpression in tumors and inflammatory cells is a consequence and manifestation of the disease state, rather than a causative factor.

Interestingly, in vivo pharmacological data revealed that chronic treatment with A3AR agonist in various experimental animal models of cancer and inflammation did not desensitize the receptor. This was evidenced by the downregulation of receptor expression levels shortly after the last drug administration in a chronic mode of treatment [6,7,32]. In addition, 24 hours after the last agonist administration, A3AR protein expression level was fully recovered to the control level, demonstrating that chronic treatment does not reduce the receptor expression levels [32].

IV. In vivo pharmacological profile of A3AR agonists

A. Anticancer effect

In experimental animal models, A3AR agonists were efficacious in combating growth of solid tumors, including melanoma, prostate, colon and hepatocellular carcinoma (Table 1). The agonists showed efficacy upon chronic oral treatment, which was initiated after the tumor was already established. Overall, the drugs were much more potent in the syngeneic rather than in the xenograft models, pointing towards an immunological effect on top of the direct anticancer effect. Supporting this notion are the findings showing that treatment with 2 increased interleukin-12 and potentiated NK activity in an animal model of melanoma [33].

Table 1.

Effects of A3AR agonists on growth of solid tumors in experimental animal models.

| Inflammatory Condition | Experimental animal model | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Adjuvant & collagen-induced arthritis | [7, 38, 68–70] |

| Osteoarthritis | Monosodium iodoacetate-induced osteoarthritis | [71] |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | Dextran sodium sulphate or 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis; Spontaneous colitis in interleukin-10 gene deficient mice | [26, 37. 72] |

| Uveitis | IRBP induced Experimental autoimmune uveitis | [73] |

| Sepsis/toxemia | CLP and LPS-induced sepsis | [35,74] |

| Pulmonary inflammation | LPS inhalation | [27] |

The direct mechanism of the anticancer effect of A3AR agonists entails modulation of the NF-κB and the Wnt signaling pathways. In tumor lesions of A3AR agonist-treated animals, the expression levels of PKB/Akt, IKK, NF-κB and TNF-α signaling proteins were downregulated. The expression of glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β) was upregulated, while the expresssion of its downstream proteins, β-catenin, LEF1 and c-Myc, was decreased, leading to inhibition of tumor cell growth [6,32,34]. Apoptosis, an additional mechanism of action, was demonstrated in hepatocellular carcinoma tumors, and manifested by increased expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins BAD, BAX and Caspase-3 upon treatment with 2 [6]. These data prompted the selection of 2 as a drug candidate to be developed as an anticancer agent for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.

B. Anti-inflammatory effect

A3AR agonists possess a robust anti-inflammatory effect mediated by the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines [35–37]. 1, 2 and 3 exert anti-inflammatory effects in experimental animal models of inflammatory bowel disease, systemic toxemia, pulmonary inflammation, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and liver inflammation (Table 2). The molecular mechanism involved with the anti-inflammatory activity entails de-regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to inhibition of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12, MIP-1α, MIP-2 and RANKL, resulting in apoptosis of inflammatory cells [7,38].

Table 2.

Effects of A3AR agonists in experimental animal models of inflammatory disease.

| Tumor Type | Animal strain, Cell line | Experimental model | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Mice; B16-F10 | Syngeneic; Metastatic Syngeneic; subcutaneous |

[33, 62, 63] |

| Prostate cancer | Rat; AT6.1 Mice; PC3 |

Xenograft; Metastatic Xenograft, subcutaneous |

[32, 64] |

| Colon carcinoma | Mice; HCT-116 Mice; CT-26 |

Xenograft, subcutaneous Syngeneic; Metastatic |

[34, 65, 66] |

| Breast cancer | Mice; SK-BR-3 | Xenograft, subcutaneous | [75] |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Rat; N1S1 Mice; Hep3B |

Syngeneic; Orthotopic Xenograft, subcutaneous |

[6, 67] |

C. Protective effects

Chemoprotective effect

Myelotoxicity is a severe and dose-limiting complication of chemotherapy. Drug-induced myelosuppression is a major toxic factor that limits the administration of larger, potentially more effective doses of chemotherapy.

A3AR agonists administered in combination with chemotherapeutic agents to tumor-bearing mice prevented the myelotoxic effects of chemotherapy [39]. Coadministration of 1 prevented a decline in white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil counts, resulting in full recovery of myeloid system parameters. The A3AR agonist induced production of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), which stimulates myeloid progenitor cell expansion in the bone marrow and increases the WBC and neutrophil counts in the peripheral blood. The molecular mechanism underlying the events prior to G-CSF production includes the upregulation of its transcription factor NF-κB and the upstream kinases PI3K, PKB/Akt and IKK[39].

In the cardiovascular system, A3AR agonists induce cardioprotection against chemotherapy-induced damage. The anthracycline antibiotic doxorubicin (DOX) or adriamycin has been an effective treatment for leukemias, lymphomas and solid tumors including breast cancer. Acute cardiotoxicity of DOX develops during and shortly after the initiation of therapy. However, chronic or late DOX-induced cardiotoxicity has a latency lasting for years prior to the development of overt heart failure. Currently, only dexrazoxane, a free-radical scavenger, shows promise as a cardioprotective agent during DOX treatment [40]. Developing new methods to reduce both acute and chronic cardiotoxicity should increase the effectiveness of this anticancer therapy.

In this context, it is interesting to note that the A3 agonist 2 can protect against mitochondrial damage and helps preserve ATP production in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. Repeated i.v. injection of 2 prior to DOX administration in rats helped prevent left ventricular wall thinning and dysfunction [41,42]. Whether continuous treatment with 2 can delay or prevent the late DOX cardiotoxicity is unknown.

Cardioprotective anti-ischemic effect

A3AR agonists protect against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (I/R), which has been demonstrated using selective agonists and A3AR-knockout mice, which are otherwise physiologically normal [43]. The cardioprotective effect is evident in role of the A3AR in ischemic preconditioning and in direct protection during ischemia. The A3AR may also be involved in mediating the post-conditioning effect given its ability to reduce infarct size when it is administered during reperfusion [9]. The A3AR has the lowest level of myocardial expression among the ARs, at least for the murine heart. However, evidence has accumulated indicating that stimulation of an endogenous cardiac A3AR, independent of circulating immune inflammatory cells or resident mast cells, can result in cardioprotection [44]. An anti-inflammatory action of the A3AR in vivo may also contribute importantly to the cardioprotective effect of A3 agonist. Both a direct cardioprotective mechanism and an anti-inflammatory effect exerted at the immune cell level in vivo may be important. Future studies are needed to address this question. A cardioprotective role of the A3AR was also found in non-rodent mammals such as rabbits and dogs [45,46].

Mediators for a direct myocardial protective effect include protein kinase C (PKC), KATP channels, reactive oxygen species, connexin 43, mitochondrial permeability transition pore (MPTP), and GSK-3β. Thus, a signaling cascade may begin with A3AR stimulation, PKC activation, phosphorylation (and thus inactivation) of GSK-3β, leading to inhibition of MPTP and reduced cardiac myocyte death [47]. The role of sarcolemmal vs. that of mitochondrial KATP channels in mediating the A3 cardioprotection is not clear. There is extensive evidence for a protective role of mitochondrial KATP (mito KATP) channel including the recently elucidated function of connexin 43 in mediating mito KATP opening by PKC. A recent study, however, showed that sarcolemmal KATP deletion abrogated the preconditioning effect of A3AR agonist in murine heart [43]. Given the redundancy of signaling pathways causing cardioprotection, it is possible that species differences exist in the role of such signaling molecules. Genetic background could also modulate cardioprotection not only in mice but also humans.

Protection of skeletal muscle

A3AR agonists attenuate skeletal muscle injury caused by ischemia and reperfusion or eccentric exercise [48]. Skeletal muscle is susceptible to various forms of injury, including ischemia, trauma, and physical exertion. Skeletal muscle is one of the most vulnerable tissues in the extremities. Developing new methods designed to provide cytoprotection to the skeletal muscle is thus important. Direct infusion of adenosine can mimic the skeletal muscle protective effect of ischemic preconditioning in extensor digitorum longus muscle before aorta occlusion in the rat as well as in the pig latissimus dorsi muscle flap model. A3AR agonist, when administered in vivo, signals selectively via phospholipase PLCβ2/β3 to cause a reduction in skeletal muscle injury sustained either during ischemia/reperfusion or eccentric exercise [48]. While A1 and A2AARs can also mediate anti-ischemic protection in skeletal muscle, only the A3AR can induce protection against both I/R and eccentric exercise injuries.

Given that activation of the A3AR has a known anti-inflammatory effect, it is possible that skeletal muscle protective effect is mediated, at least, in part at an immune cell level. The following lines of evidence support this hypothesis. First, activated mast cells and neutrophils are important contributors of skeletal muscle ischemia/reperfusion damage. Second, activation of the A3AR can block superoxide formation and chemotaxis of murine bone marrow neutrophils [49].

Lung ischemia/reperfusion protection

A3AR agonist prevents lung injury following ischemia/reperfusion in the cat. Compound 3 produced a sustained protection, which was associated with suppressed p38 protein expression and downregulation of its phosphorylation [50,51].

Neuroprotection

Evidence from diverse models suggests that neuroprotective effects may be mediated by the A3AR, but differences between acute and chronic agonist administration have been noted [10]. Ischemic brain injury in a model of forebrain ischemia in gerbils is reduced upon chronic treatment with 1 [52]. A3AR agonist was found to prevent the loss of retinal ganglion cells following activation of the P2×7 receptor in a rat experimental model [53].

V. CF101 for the treatment of inflammatory and ophthalmic diseases

Based on the pre-clinical pharmacology data and encouraging safety data in Phase I studies [54], the anti-inflammatory effect of 1 was tested in a set of three Phase II clinical studies including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), psoriasis and dry eye syndrome (Table 3). Overall, the data obtained from these clinical studies showed excellent safety profile and efficacy, positioning 1 as a disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drug.

Table 3.

Past and present human clinical studies utilizing CF101 and CF102.

| Disease | Phase | Primary endpoints | Refs. | Current status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2a | ACR20 response at week 12 | [56] | Phase 2b |

| Psoriasis | 2 | Reduction in PASI score of at least 75% from Baseline (PASI 75) to the end of the 12 weeks treatment period | [57] | Phase 2/3 |

| Dry eye syndrome | 2 | Improvement of 25% or more over baseline at week 12 in tear film BUT or in superficial punctate keratitis as assessed by either FS or ST1 results | [60] | Phase 3 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 1/2 | To determine the safety, tolerability, dose-limiting toxicities, maximum tolerated dose, recommended Phase 2 dose and to assess the repeat-dose pharmacokinetic behavior of orally administered CF102 | Ongoing | |

| Hepatitis C virus infection | 1/2 | To determine the safety and tolerability of 15 days of orally administered CF102 in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 1, to assess the effects on HCV load during 24 weeks and to assess the repeat-dose pharmacokinetic behavior of CF102 | Ongoing |

FS = fluorescein staining ST1 = Schirmer shear test 1

A. Rheumatoid Arthritis

A chronic, systemic inflammatory disorder attacking the joints resulting in inflammatory synovitis that may progress to the destruction of articular cartilage and bone [55]. The mechanisms responsible for causing joint damage and functional impairment in RA are complicated and involve B cell or T cell products stimulating the release of TNF and other pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and TNF-α and degradative enzymes.

In a multi-center Phase II study, blinded to dose (0.1, 1.0, or 4.0 mg), the drug was administered orally, twice daily for 12 weeks to patients with active RA. The primary efficacy endpoint was an improvement of 20% or more according to the classification of RA responses by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [55]. Compound 1 was found to be safe and well tolerated, and the maximal responses were observed in patients treated with a 1.0 mg dose. At 12 weeks, 55.6%, 33.3%, and 11.5% of the patients receiving 1.0 mg 1 achieved ACR20%, 50%, and 70% responses, respectively. In addition, a statistically significant correlation between A3AR expression at baseline and patient response to 1 was observed, rendering the A3AR as a biological predictive marker [56].

B. Psoriasis

A chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by epidermal hyper-proliferation and immature differentiation resulting in multisystem pathology and a negative impact on the quality of life of the patients [57]. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as INF-γ, TNF-α, IL-23 and Th17 are known to play a role in mediating the inflammation and epidermal alterations in psoriasis [58].

The efficacy and safety of 1 were tested in a Phase II, multicenter, randomized, double blind, dose-ranging, placebo-controlled study in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque-type psoriasis. Compound 1 (1, 2, or 4 mg) or placebo was administered orally twice daily for 12 weeks. Overall, the drug was safe and well tolerated.

The maximal improvement in the mean change from baseline in the PASI (psoriasis area and severity index) score vs. placebo and the highest percentage of patients who achieved PGA (physician‘s global assessment) score of 0 or 1 were observed in the 2 mg 1-treated group. The improvement was progressive and linear throughout the study period. Thus, 1 was safe and well tolerated.

C. Dry Eye Syndrome

An inflammatory condition of the eye that is caused by decreased tear production or increased tear film evaporation. It is characterized by massive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. The dryness and the inflammation could result in eye damage leading to impaired vision [59,60].

Anecdotal findings demonstrating that 1 improved indicators of dry eye syndrome in RA patients led to a separate randomized, multi-center, doubled-masked, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, Phase II clinical study of the safety and efficacy of 1 (1 mg) administered orally daily for 12 weeks to patients with moderate-to-severe dry eye syndrome. Conpound 1 was safe and well tolerated and no serious adverse events were noted throughout the study. Treatment with 1 resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the mean change from baseline at week 12 of the clearance of corneal staining, tear break-up time and tear meniscus height in the group treated with 1 vs. placebo. Compound 1 was well tolerated and exhibited an excellent safety profile with no serious adverse events. Interestingly, a statistically significant decrease from baseline was observed in the intraocular pressure of the 1-treated patients in comparison to the placebo-treated group [61].

No serious adverse events in the RA, psoriasis or dry eye clinical studies were observed. The profile of the adverse events was similar between the placebo and 1-treated groups.

VI. Conclusions

Based on the experimental animal data and human clinical study results presented in the current review, A3AR is suggested as a specific and unique therapeutic target to combat proliferative diseases including inflammation and cancer. The excellent safety profile of A3AR agonists, currently tested in human clinical studies, is attributed to the different protective effects mediated via the receptor. The A3AR has also been identified as a biological marker to predict a patient‘s eligibility for treatment with the agonists. Taken together, the utilization of A3AR as both a biological predictive marker and a therapeutic target encompass the a ‘personalized medicine’ approach and make A3AR agonists promising small molecule drug candidates.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Ray Neag Distinguished Professorship (to BTL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Salvatore CA, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human A3 adenosine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90:10365–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fredholm BB, et al. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors – An update. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63:1–34. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gessi S, et al. Elevated expression of A3 adenosine receptors in human colorectal cancer is reflected in peripheral blood cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;210:5895–5901. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1134-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madi L, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor is highly expressed in tumor vs. normal cells: Potential target for tumor growth inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:4472–4479. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ochaion A, et al. The anti-inflammatory target A3 adenosine receptor is overexpressed in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and Crohn’ s disease. Cell. Immunol. 2009;258:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bar-Yehuda S, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF102 induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma via de-regulation of the Wnt and NF-κB signal transduction pathways. Int. J. Oncol. 2008;33:287–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fishman P, et al. The PI3K-NF-κ B signal transduction pathway is involved in mediating the anti-inflammatory effect of IB-MECA in adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Res. Therap. 2006;8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/ar1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varani K, et al. Expression and functional role of adenosine receptors in regulating inflammatory responses in human synoviocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010;160:101–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ge ZD, et al. A3 adenosine receptor activation during reperfusion reduces infarct size through actions on bone marrow-derived cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2010;49:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobson KA. A3 adenosine receptors: Novel ligands and paradoxical effects. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:184–191. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(98)01203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klaasse EC, et al. Internalization and desensitization of adenosine receptors. Purinerg. Signal. 2008;4:21–37. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9086-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao ZG, Jacobson KA. Translocation of arrestin induced by human A3 adenosine receptor ligands in an engineered cell line: Comparison with G protein-dependent pathways. Pharmacol. Res. 2008;57:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koscsó B, et al. Investigational A3 adenosine receptor targeting agents. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2011;20:757–768. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2011.573785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dal Ben D, et al. Molecular modeling study on potent and selective adenosine A3 receptor agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:7923–7930. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tosh DK, et al. Functionalized congeners of A3 adenosine receptor-selective nucleosides containing a bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane ring system. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:7580–7592. doi: 10.1021/jm900426g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wadzak W, et al. Preparation and first evaluation of [18F]FE@SUPPY: a new PET tracer for the adenosine A3 receptor. Nuclear Med. Biol. 2008;35:61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fozard JR. From hypertension (+) to asthma: Interactions with the adenosine A3 receptor from a personal perspective. Chapter 1. In: Borea PA, editor. A3 Adenosine Receptors from Cell Biology to Pharmacology and Therapeutics. Springer; 2010. pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao ZG, et al. Functionally biased modulation of A3 adenosine receptor agonist efficacy and potency by imidazoquinolinamine allosteric enhancers. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2011;82:658–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim SH, et al. Functional variability of the adenosine A3 receptor (ADORA3) gene polymorphism in aspirin-induced urticaria. Br. J. Dermatol. 2010;163:977–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09983.x. 61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gessi S, et al. A3 adenosine receptors in human neutrophils and promyelocytic HL60 cells: a pharmacological and biochemical study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:116–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yao Y, et al. Adenosine A3 receptor agonists protect HL-60 and U-937 cells from apoptosis induced by A3 antagonists. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;232:317–322. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trincavelli ML, et al. A3 adenosine receptors in human astrocytoma cells: agonist-mediated desensitization, internalization, and down-regulation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002;62:1373–1384. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.6.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merighi S, et al. Pharmacological and biochemical characterization of adenosine receptors in the human malignant melanoma A375 cell line. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1215–1226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suh BC, et al. Pharmacological characterization of adenosine receptors in PGT-beta mouse pineal gland tumour cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:132–142. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morello S, et al. Cl-IB-MECA inhibits human thyroid cancer cell proliferation independently of A3 adenosine receptor activation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2008;7:278–284. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.2.5301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guzman J, et al. ADOA3R as a therapeutic target in experimental colitis: proof by validated high-density oligonucleotide microarray analysis. Inflamm. Bowel. Dis. 2006;12:766–789. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wagner R, et al. Adenosine receptor A3 is a critical mediator in LPS-induced pulmonary inflammation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2010;299:L502–L512. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00083.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schlötzer-Schrehardt U, et al. Selective upregulation of the A3 adenosine receptor in eyes with pseudoexfoliation syndrome and glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:2023–2034. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madi L, et al. Over-expression of A3 adenosine receptor in PBMNC of rheumatoid arthritis patients: Involvement of NF-κB in mediating receptor level. J. Rheumatol. 2007;34:20–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keibel A, et al. Inflammation, microenvironment, and the immune system in cancer progression. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2009;15:1949–1955. doi: 10.2174/138161209788453167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ariztia EV, et al. The tumor microenvironment: key to early detection. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2006;43:393–425. doi: 10.1080/10408360600778836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fishman P, et al. Targeting the A3 adenosine receptor for cancer therapy: inhibition of prostate carcinoma cell growth by A3 agonist. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2077–2083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harish A, et al. A3 adenosine receptor agonist potentiates natural killer cell activity. Int. J. Oncol. 2003;23:1245–1249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fishman P, et al. An agonist to the A3 adenosine receptor inhibits colon carcinoma growth in mice via modulation of GSK-3β and NF-κB. Oncogene. 2004;23:2465–2471. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hasko G, et al. Adenosine receptor agonists differentially regulate IL-10, TNF-alpha, and nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages and in endotoxemic mice. J. Immunol. 1996;157:4634–4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasko G, et al. An agonist of adenosine A3 receptors decreases interleukin-12 and interferon-γ production and prevents lethality in endotoxemic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998;358:261–268. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mabley J, et al. The adenosine A3 receptor agonist, N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5‘-N-methyluronamide, is protective in two murine models of colitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 466:323–329. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01570-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabó C, et al. Suppression of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1alpha production and collagen-induced arthritis by adenosine receptor agonists. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:379–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bar-Yehuda S, et al. Agonists to the A3 adenosine receptor induce G-CSF production via NF-kappaB activation: a new class of myeloprotective agents. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:1390–1398. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00962-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang YW, et al. Cardiomyocyte death in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. (Warsz) 2009;57:435–445. doi: 10.1007/s00005-009-0051-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shneyvays V, et al. Activation of A3 adenosine receptor protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2001;33:1249–1261. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emanuelov AK, et al. Adenosine A3 receptor-mediated cardioprotection against doxorubicin-induced mitochondrial damage. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wan TC, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor agonist CP-532,903 [N6-(2,5-dichlorobenzyl)-3'-aminoadenosine-5'-N-methylcarboxamide] protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via the sarcolemmal ATP-sensitive potassium channel. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008;324:234–243. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.127480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Auchampach JA, et al. Canine mast cell adenosine receptors: Cloning and expression of the A3 receptor and evidence that degranulation is mediated by the A2B receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 1997;52:846–860. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Auchampach JA, et al. A3 adenosine receptor agonist IB-MECA reduces myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in dogs. Am. J. Physiol. Heart. Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H607–H613. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01001.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auchampach JA, et al. Selective activation of A3 adenosine receptors with N6-(3-iodobenzyl)adenosine-5'-N-methyluronamide protects against myocardial stunning and infarction without hemodynamic changes in conscious rabbits. Circ. Res. 1997;80:800–809. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.6.800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park SS, et al. N6-(3-iodobenzyl)-adenosine-5'-N-methylcarboxamide confers cardioprotection at reperfusion by inhibiting mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening via glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006;318:124–131. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng J, et al. Protective roles of adenosine A1, A2A, and A3 receptors in skeletal muscle ischemia and reperfusion injury. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007;293:H3685–H3691. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00819.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van der Hoeven D, et al. Activation of the A3 adenosine receptor suppresses superoxide production and chemotaxis of mouse bone marrow neutrophils. Mol. Pharmacol. 2008;74:685–696. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.048066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matot I, et al. A3 adenosine receptors and mitogen-activated protein kinases in lung injury following in vivo reperfusion. Crit Care. 2006;10:R65. doi: 10.1186/cc4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Matot I, et al. Lung injury after in vivo reperfusion: outcome at 27 hours after reperfusion. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:269–278. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f5b90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.von Lubitz DK, et al. Chronic administration of adenosine A3 receptor agonist and cerebral ischemia: neuronal and glial effects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;367:157–163. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00977-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu H, et al. Stimulation of the P2X7 receptor kills rat retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Exp. Eye. Res. 2010;91:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Troostenburg AR, et al. Tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and concentration-dependent hemodynamic effects of oral CF101, an A3 adenosine receptor agonist, in healthy young men. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004;42:534–542. doi: 10.5414/cpp42534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris ED. Rheumatoid arthritis: pathophysiology and implications for therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990;322:1277–1289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005033221805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silverman MH, et al. Clinical evidence for utilization of the A3 adenosine receptor as a target to treat rheumatoid arthritis: Data from a phase II clinical trial. J. Rheumatol. 2008;35:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Christophers E. Psoriasis—epidemiology and clinical spectrum. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2001;26:314–320. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Asarch A, et al. Th17 cells: a new paradigm for cutaneous inflammation. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2008;19:259–266. doi: 10.1080/09546630802206686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Latkany R. Dry eyes: etiology and management. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 2008;19:287–291. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3283023d4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Acera A, et al. Inflammatory markers in the tears of patients with ocular surface disease. Ophthal. Res. 2008;40:315–321. doi: 10.1159/000150445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Avni I, et al. Teatment of dry eye syndrome with orally administered CF101: Data from a phase 2 clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1287. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.11.029. 129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fishman P, et al. The A3 adenosine receptor as a new target for cancer therapy and chemoprotection. Exp. Cel.l Res. 2001;269:230–236. doi: 10.1006/excr.2001.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madi L, et al. A3 adenosine receptor activation in melanoma cells: association between receptor fate and tumor growth inhibition. JBC. 2003;278:42121–42130. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jajoo S, et al. Adenosine A3 receptor suppresses prostate cancer metastasis by inhibiting NADPH oxidase activity. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1132–1145. doi: 10.1593/neo.09744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ohana G, et al. Inhibition of primary colon carcinoma growth and liver metastasis by the A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF101. British J. Cancer. 2003;89:1552–1558. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bar-Yehuda S, et al. CF101, an Agonist to the A3 adenosine receptor enhances the chemotherapeutic effect of 5-flurouracil in a colon carcinoma murine model. Neoplasia. 2005;7:85–90. doi: 10.1593/neo.04364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cohen S, et al. CF102 an A3 adenosine receptor agonist mediates anti-tumor and anti-inflammatory effects in the liver. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011;226:2438–2447. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baharav E, et al. The anti-inflammatory effect of A3 adenosine receptor Agonists in murine autoimmune arthritis models. J. Rheumatol. 2005;32:469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rath-Wolfson L, et al. IB-MECA, an A3 adenosine receptor agonist prevents bone resorption in rats with adjuvant induced arthritis. Clin. & Exp. Rheumatology. 2006;24:400–4068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ochaion A, et al. Methotrexate enhances the anti-inflammatory effect of CF101 via up-regulation of the A3 adenosine receptor expression. Arthritis. Res. Ther. 2006;8:R169. doi: 10.1186/ar2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bar-Yehuda S, et al. Induction of an antiinflammatory effect and prevention of cartilage damage in rat knee osteoarthritis by CF101 treatment. Arthritis. Rheum. 2009;60:3061–3071. doi: 10.1002/art.24817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Antonioli L, et al. Control of enteric neuromuscular functions by purinergic A3 receptors in normal rat distal colon and experimental bowel inflammation. Br. J Pharmacol. 2010;161:856–871. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00917.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bar Yehuda S, et al. Inhibition of experimental auto-immune uveitis by the A3 adenosine receptor agonist CF101. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011;28:727–731. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2011.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee HT, et al. A3 adenosine receptor activation decreases mortality and renal and hepatic injury in murine septic peritonitis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2006;291:R959–R969. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00034.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chung H, et al. The antitumor effect of LJ-529, a novel agonist to A3 adenosine receptor, in both estrogen receptor-positive and estrogen receptor-negative human breast cancers. Mol. Cancer. Ther. 2006;5:685–692. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappa B in cancer development and progression. Nature. 2006;441:431–436. doi: 10.1038/nature04870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhai P, et al. Differential roles of GSK-3β during myocardial ischemia and ischemia/reperfusion. Circ. Res. 2011;109:502–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]