Abstract

AIM: To investigate potential gender differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, cardiovascular disease (CVD) management, and prognosis in acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

METHODS: A systematic literature search was performed through Medline using pre-specified keywords. An additional search was performed, focusing specifically on randomized controlled clinical trials in relation to therapeutic intervention and prognosis. In total, 92 relevant articles were found.

RESULTS: Women with CVD tended to have more hypertension and diabetes at the time of presentation, whereas men were more likely to smoke. Coronary angiography and revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention were performed more often in men. Women were at a greater risk of short-term mortality and complications after revascularization. Interestingly, women under 40 years presenting with ACS were at highest risk of cardiovascular death compared with men of the same age, irrespective of risk factors. This disadvantage disappeared in older age. The long-term mortality risk of ACS was similar in men and women, and even in favor of women.

CONCLUSION: Mortality rates are higher among young women with ACS, but this difference tends to disappear with age, and long-term prognosis is even better among older women.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Gender, Myocardial infarction, Coronary artery bypass grafting, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Postoperative complications, Mortality, Prognosis, Estrogens

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an important cause of death among both men and women. In women, CVD develops 7 to 10 years later than in men, potentially because of a protective effect of estrogens. However, CVD is the main cause of death among women and its occurrence narrows women’s survival advantage over men[1]. In most parts of the world, the mortality rate has declined in the last 30 years, except for Eastern Europe and China[2]. In the United States in 2007, 391 886 men died because of CVD, compared with 421 918 women[3], while 10 years previously the mortality rate of CVD in men was significantly higher in several countries[4]. Some studies have suggested gender differences in presentation and treatment of CVD and acute coronary syndrome (ACS), but there are many uncertainties and discrepancies between these studies[4,5]. Besides differences in presentation, women also seem to have different abnormalities with regard to electrocardiography and scintigraphy, compared with men[4]. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of what is known nowadays with respect to possible gender differences in cardiovascular risk factors, therapy and prognosis of ACS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A systematic literature search was performed through Medline using pre-specified keywords. The following keywords with synonyms were used for selecting relevant studies: CVD, coronary artery disease (CAD), ACS/event, ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction (MI), gender, sex, women, men, differences, estrogens, hormone replacement therapy (HRT), coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG), percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), revascularization, readmission, postoperative complications, outcome, and hospital mortality. Only studies that included both men and women were eligible for review. Of 2260 articles found, 199 articles appeared relevant after screening of the title and abstract. Furthermore, through a search of the references in the articles obtained by these keywords, 30 additional relevant articles were found.

A more focused exclusion of articles was then performed in relation to therapy and prognosis of ACS. Articles published before 2000 were excluded, because therapy, operative techniques and thereby prognosis have a high tendency to change over time. Selected articles included patients with ACS, unstable angina, acute MI, ST elevation MI (STEMI) and non-STEMI, and subsequently compared women with men. This provided 152 articles. After screening of the full text, a total of 92 articles were found to be relevant and valid.

RESULTS

Epidemiology

The prevalence of CVD increased with age and was higher among men. The prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD) in the United States was 37.4% in men and 35.0% in women in 2008, with a mortality rate of 48.2% and 51.8% in men and women, respectively, in 2007. The prevalence of CHD in men and women of 20 years and older was 8.3% and 6.1%, respectively. When comparing different countries, France and Japan had the lowest prevalence of CHD for both men and women (Table 1)[3]. Although the incidence of CVD remained higher in men compared with women, figures of the last 30 years showed a declining incidence of CVD in men, while the incidence in women remained relatively stable. In North America CVD is the leading cause of hospital admission for both men and women. However, in women hospital stay tended to be longer and they experienced higher levels of pain, disability and discomfort, compared with men[2]. In the United States in 2007, one out of three deaths was caused by CVD and one out of six was due to CHD. However, the risk of heart disease in women often seemed to be underestimated, with CVD the major cause of death in women older than 75 years[3].

Table 1.

Mortality rates of coronary heart disease per 100 000 population by gender[3]

| Country | Year1 | Men 35-74 yr | Women 35-74 yr |

| United States | 2007 | 153.3 | 60.4 |

| The Netherlands | 2008 | 66.2 | 22.8 |

| England/Wales | 2007 | 138.3 | 43.4 |

| Denmark | 2006 | 84.8 | 32.4 |

| France | 2007 | 48.4 | 12.2 |

| Germany | 2006 | 125.3 | 38.2 |

| Italy | 2007 | 75.6 | 22.2 |

| Russian Federation | 2006 | 706.0 | 237.1 |

| China | 2000 | 108.3 | 71.9 |

| Japan | 2008 | 47.6 | 13.8 |

| Australia | 2006 | 88.9 | 26.8 |

| New Zealand | 2005 | 138.4 | 47.2 |

| Argentina | 1996 | 140.3 | 39.4 |

Most recent year available.

Risk factors

The INTERHEART study identified nine different global risk factors for an acute MI, namely smoking, history of hypertension or diabetes, waist/hip ratio, dietary patterns, physical activity, consumption of alcohol, blood apolipoproteins, and psychosocial factors. Altogether, they could predict the risk of an acute MI as 90% in men and 94% in women. Although most of these classic risk factors were of equal clinical significance in both men and women[6], women who presented with ACS more often had hypertension[7-61], diabetes[7-10,12,13,15-17,20,22-25,27,28,30-32,34-36,38,39,41-43,45-47,49-54,57-66], hypercholesterolemia[7,9,10,13,15-17,21,22,26,28-30,35,36,50], and a history of angina[7,50], heart failure[7,45,47,52,53,59,60,63,64], and cerebrovascular events (CVA)[7,39,47,50,52,63,64] than men. On the other hand, men tended to smoke more[7-10,13-17,19-22,25,26,28,30,31,33-44,46,47,49-51,53-56,62,66] and were more likely to have a history of MI[7-9,14,16,18,19,21-23,28-32,36,39,41,43,45,47,51,53-56,58,64] and prior CABG[7-10,12,13,15-17,23,28,30,31,34,39,43,44,54,55,62-64,67] as shown in Table 2. Although women smoked less, the relative risk (RR) for developing a MI was 1.57 (95% CI: 1.25-1.97) among smoking women in comparison to smoking men and this increased risk was pronounced in women at younger age (< 55 years)[68]. The prevalence of fatal CHD was substantially higher in patients with diabetes, in comparison to patients without diabetes (5.4% vs 1.6%). Among women, this effect of diabetes on mortality was even stronger, with a RR of 3.50 (95% CI: 2.70-4.53), compared with a RR of 2.06 (95% CI: 1.81-2.34) among men with diabetes vs no diabetes[69]. Women with ACS more often had a family history of CAD[23,33,70]. However, a family history of premature CAD was not a risk factor overall for in-hospital mortality[71]. The cardiovascular risk burden tended to be higher in women aged younger than 46 years, compared with men of the same age. Of all patients younger than 46 years presenting with ACS, 78.5% and 25.3% of women, respectively, had one or more than one risk factor for ACS, compared with 71.8% and 17.2%, respectively, among men (P = 0.008 and P < 0.001, respectively)[24]. Peirera et al[72] studied differences in hypertension between men and women as an important risk factor for CVD. Apart from the fact that women received treatment more often, they also had a greater awareness of the risk of hypertension for CVD. In both developing and developed countries, awareness, control and treatment of hypertension was significantly higher in women, compared with men. On the other hand, women were categorized at high-risk of CVD in risk assessment programs if a history of diabetes, stroke or chronic kidney disease was present[73], and all these conditions were generally more prevalent in women, compared with men, as noted above.

Table 2.

Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and history of myocardial infarction and cardiac surgery stratified by gender

| Author | Design | Study population | Patients | Age (mean, yr) | P | Hypertension (%) | P | Diabetes (%) | P | Smoking (%) | P | History of MI (%) | P | History of cardiac surgery (%) | P | ||||||||

| study/date | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||||

| Reynolds et al[30] 2007 | RCT | MI | 12 498 | 4090 | 59.5 | 67.0 | < 0.001 | 29.7 | 47.3 | < 0.001 | 14.4 | 21.0 | < 0.001 | 49.7 | 34.3 | < 0.001 | 16.4 | 12.5 | < 0.001 | CABG | 3.7 | 2.2 | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 7.5 | 4.5 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Moriel et al[28] 2005 | Pros cohort | ACS | 820 | 511 | 78 | 79 | 0.12 | 58 | 74 | < 0.001 | 33 | 40 | 0.007 | 13 | 5 | < 0.001 | 39 | 29 | < 0.001 | CABG | 14 | 7 | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 21 | 11 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Herlitz et al[18] 2009 | Retro cohort | AMI | 835 | 588 | 72.7 | 79.2 | < 0.0001 | 46 | 56 | 0.01 | 24 | 21 | NS | 22 | 16 | NS | 42 | 33 | < 0.0001 | CABG | 10 | 7 | 0.06 |

| PCI | 7 | 5 | 0.32 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mehilli et al[54] 2002 | Pros cohort | AMI | 1435 | 502 | 60.7 | 70.3 | < 0.001 | 61.0 | 72.9 | < 0.001 | 18.0 | 25.3 | < 0.001 | 43.1 | 25.9 | < 0.001 | 22.1 | 16.3 | 0.001 | CABG | 6.1 | 3.4 | 0.02 |

| PCI | 10.7 | 7.6 | 0.04 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Mueller et al[55] 2002 | Pros cohort | MI | 1033 | 417 | 64 | 68 | 0.01 | 60 | 72 | 0.01 | 19 | 23 | 0.15 | 33 | 21 | 0.01 | 37 | 24 | 0.01 | CABG | 17 | 6 | 0.01 |

| PCI | 24 | 21 | 0.20 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Toumpoulis et al[34] 2006 | Pros cohort | CABG | 2598 | 1162 | 63.2 | 66.2 | < 0.001 | 65.9 | 79.4 | < 0.001 | 28.8 | 45.5 | < 0.001 | 16.1 | 12.9 | 0.011 | 50.7 | 46.1 | 0.010 | CABG | 7.8 | 5.3 | 0.006 |

| PCI | 10.9 | 12.8 | 0.093 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Dallongevillle et al[15] 2010 | Pros cohort | ACS | 6698 | 2268 | 62.2 | 65.8 | < 0.0001 | 80.3 | 87.9 | < 0.0001 | 33.6 | 38.4 | 0.009 | 19.3 | 11.0 | < 0.0001 | 19.1 | 20.6 | < 0.0001 | CABG | 20.4 | 17.2 | < 0.0001 |

| Anand et al[9] 2005 | Trial | ACS | 7726 | 4836 | 62.7 | 66.5 | 0.0001 | 53 | 68.8 | 0.0001 | 20.9 | 24.6 | 0.0001 | 76.4 | 37.4 | 0.0001 | 36.9 | 23.9 | 0.0001 | CABG | 13.3 | 6.8 | 0.0001 |

| PCI | 11.5 | 7.2 | 0.0001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Matsui et al[26] 2002 | Retro cohort | AMI | 346 | 136 | 62.9 | 70.4 | 44 | 54 | 0.047 | 25 | 33 | 0.078 | 60 | 19 | 0.001 | 18 | 15 | 0.517 | CABG | 1 | 1 | 0.556 | |

| PCI | 12 | 4 | 0.016 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Tizón-Marcos et al[33] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 1050 | 298 | 59.7 | 62.5 | 49 | 59 | 0.004 | 17 | 20 | 0.19 | 32 | 36 | 0.23 | 45 | 41 | 0.19 | CABG | 6.3 | 6.4 | 1.00 | |

| PCI | 21 | 14 | 0.016 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Reina et al[51] 2007 | Pros cohort | AMI | 4641 | 1568 | 64 | 71 | < 0.01 | 41.0 | 61.1 | < 0.01 | 25.5 | 41.2 | < 0.01 | 53.6 | 15.7 | < 0.01 | 16.6 | 13.0 | < 0.01 | Total | 7.2 | 12.0 | < 0.01 |

| Thompson et al[53] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 807 | 359 | 61.7 | 67.7 | < 0.001 | 59.3 | 67.8 | 0.006 | 23.8 | 30.1 | 0.03 | 47.4 | 38.5 | 0.005 | 25.2 | 22.4 | 0.33 | CABG | 8.3 | 7.2 | 0.53 |

| PCI | 28.3 | 24.6 | 0.20 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lee et al[78] | Pros cohort | STEMI | 2954 | 1083 | 60.7 | 72.1 | < 0.001 | 40.2 | 59.7 | < 0.001 | 23.1 | 31.4 | < 0.001 | 58.8 | 14.7 | < 0.001 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 0.239 | CABG | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.330 |

| 2008 | PCI | 4.3 | 2.8 | 0.023 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Jankowski et al[46] 2007 | Pros cohort | CAD + PCI | 738 | 187 | 57.5 | 60.6 | < 0.001 | 72.6 | 87.8 | < 0.001 | 14.5 | 21.3 | < 0.05 | 13.6 | 6.4 | < 0.01 | 63.2 | 66.0 | NS | CABG | 1.5 | 0.5 | NS |

| PCI | 8.8 | 8.5 | NS | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Duvernoy et al[43] 2010 | Pros cohort | PCI | 14848 | 7877 | 61.9 | 66.9 | < 0.001 | 71.0 | 82.5 | < 0.001 | 29.2 | 38.5 | < 0.001 | 27.3 | 21.7 | < 0.001 | 36.0 | 32.6 | < 0.001 | CABG | 21.5 | 17.4 | < 0.001 |

| PCI | 41.8 | 38.9 | < 0.001 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lansky et al[22] 2005 | RCT | AMI + PTCA | 1520 | 562 | 57.0 | 66.0 | < 0.001 | 29.0 | 59.3 | < 0.001 | 14.0 | 25.7 | < 0.001 | 45.3 | 37.4 | 0.001 | 15.7 | 8.4 | < 0.001 | PCI | 12.7 | 7.1 | < 0.001 |

| Lansky et al[67] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 687 | 314 | 61.8 | 65.9 | < 0.0001 | 72.7 | 81.5 | 0.0026 | 25.7 | 36.3 | 0.0007 | 24.0 | 21.2 | 0.3711 | 21.9 | 13.6 | 0.0022 | Total | 34.1 | 25.5 | 0.0066 |

| De Luca et al[41] 2004 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 1195 | 353 | 59 | 66 | < 0.001 | 24 | 39 | < 0.001 | 8.7 | 15.8 | < 0.001 | 52.1 | 42.7 | 0.002 | 11.6 | 7.1 | 0.014 | CABG | 2.1 | 1.7 | NS |

| PCI | 5.3 | 1.7 | 0.004 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| De Luca et al[42] 2010 | Trail | STEMI | 1283 | 379 | 59 | 67 | < 0.001 | 39.1 | 52.5 | < 0.001 | 15.3 | 22.4 | < 0.001 | 56 | 36.9 | < 0.001 | 9.2 | 7.7 | 0.35 | Total | 7.7 | 7.6 | 0.93 |

| Bufe et al[62] | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 376 | 124 | 58 | 65 | < 0.001 | 66 | 54.8 | 0.055 | 11.2 | 24.2 | < 0.001 | 67.3 | 40.3 | < 0.001 | 11.7 | 8.9 | 0.479 | CABG | 5.6 | 0.8 | 0.046 |

| 2010 | PCI | 5.6 | 4.0 | 0.658 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Carrabba et al[40] 2004 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 627 | 293 | 67.7 | 76.3 | 0.001 | 45.3 | 60.1 | < 0.001 | 22.7 | 25.3 | 0.385 | 34.1 | 14.3 | < 0.001 | 17.2 | 14.7 | 0.331 | CABG | 2.6 | 1.0 | 0.129 |

| PCI | 5.9 | 2.1 | 0.010 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Lawesson et al[24] 2010 | Retro cohort | STEMI aged < 46 | 1748 | 384 | 40.8 | 40.4 | 0.14 | 13.9 | 21.7 | < 0.001 | 12.4 | 18.5 | 0.002 | 58.0 | 63.9 | 0.04 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 0.30 | CABG | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.25 |

| PCI | 2.5 | 1.9 | 0.46 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Berger et al[10] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 2953 | 1331 | 61.9 | 66.8 | < 0.001 | 66 | 78 | < 0.001 | 22 | 36 | < 0.001 | 15 | 10 | < 0.001 | 36 | 33 | 0.08 | CABG | 19 | 14 | 0.001 |

| PCI | 26 | 24 | 0.137 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chiu et al[13] | Pros cohort | PCI | 12 738 | 5301 | 62.3 | 66.5 | < 0.001 | 58 | 71 | < 0.001 | 24 | 34 | < 0.001 | 21 | 20 | 0.01 | 43 | 42 | 0.29 | CABG | 30 | 21 | < 0.001 |

| 2004 | PCI | 6 | 4 | < 0.001 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Koch et al[20] | Pros cohort | CABG | 1588 | 460 | 51.7 | 70.2 | 0.0001 | 22.5 | 36.3 | 0.0001 | 71.5 | 49.6 | 0.0001 | 14.3 | 10.7 | 0.044 | CABG | 14.4 | 7.0 | 0.0001 | |||

| 2003 | PCI | 15.4 | 16.3 | 0.6249 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Setoguchi et al[31] 2008 | Pros cohort | AMI | 317 | 1308 | 80 | 82 | < 0.001 | 71 | 80 | 0.001 | 33 | 39 | 0.03 | 15 | 10 | 0.01 | 52 | 37 | < 0.001 | CABG | 18 | 13 | 0.03 |

| PCI | 13 | 9 | 0.02 | ||||||||||||||||||||

MI: Myocardial infarction; AMI: Acute myocardial Infarction; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST elevation MI; CAD: Coronary artery disease; NS: Not significant.

Interventions

In the evaluation of CVD, coronary angiography (CAG) was less often performed in women than in men[9,11,18,30,44,49,60]. Age might be an important confounding factor in this regard, because women present with an ACS 10 years later than men, and CAGs were less likely to be performed in the elderly[28]. Age was found to be a predictor for undergoing PCI, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.98 (95% CI: 0.97-0.98) for each additional year[51,60,74]. Nevertheless, even after adjustment for age[18] and other cardiovascular risk factors[9,11], women with ACS were still less likely to have CAG or PCI[45,47,49] (OR, 0.70; 95% CI: 0.64-0.76)[75]. In men and women younger than 46 years, no differences were seen in the number of performed angiograms[24]. In ACS patients who underwent CAG, an equal number of men and women received a PCI afterwards[18,30,60,66]. In STEMI patients, results were inconsistent. Some studies found no significant differences in the number of CAGs and PCIs performed after adjustment for age[40,44,50,51], while Radovanovic et al found that women with both STEMI and non-STEMI underwent primary PCI less often (30.9% and 22.0%, respectively) compared with men (40.3% and 30.9%, respectively). This difference persisted after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors (OR, 0.70) and after adjustment for age alone (OR, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.63-0.80)[58,74].

The mortality rate for ACS was highest among female patients who did not undergo a CAG; 12.9% vs 4.7% in those who underwent a CAG, compared with 5.6% and 2.9%, respectively, in men[30]. A higher mortality rate among women compared with men was also reported in patients who suffered a STEMI. A possible explanation may be the higher rate of comorbidity in women and a greater delay between onset of complaints and arrival at the emergency department compared with men. At 6 mo follow-up, no significant differences in mortality were present[28].

Several studies compared the coronary anatomy of men and women presenting with ACS. In general, women tended to have a smaller diameter of coronary arteries, in proportion with the lower body surface area, and this was associated with a higher mortality rate[13,16,20,22,34,36,43,53,75,76]. Women more often had one-vessel disease[8,19,23,24,34,43,52,62,67] and less often three-vessel disease[8,9,19,23-25,34,43,55,66,67] as shown in Table 3. Multiple vessel disease was associated with a higher mortality rate[77]. In addition, women with ACS had less extensive obstructive CAD, whereas men not only had more lesions, but also lesions of greater length and complexity[23]. Nevertheless, among patients who underwent PCI no differences were seen between men and women in the number of stents placed; 69% vs 66%[19] and 77% vs 77%[10]. Furthermore, no differences were found in length or diameter of the stents placed, nor in success rate of the performed PCI[25,41,43,46,48,53,56,57,59,78]. It remains uncertain whether women would benefit as much as men from early invasive strategy in the case of an ACS, because the power of the different studies was limited[14,21].

Table 3.

Extent of coronary artery disease stratified by gender

| Author study/date | Design | Study population | Patients | Age (mean, yr) | P | 1 vessel disease (%) | P | 3 vessel disease (%) | P | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||||||

| Lansky et al[22] 2005 | RCT | AMI + PTCA | 1520 | 562 | 57.0 | 66.0 | < 0.001 | 51.1 | 51.6 | NS | 15.7 | 15.3 | NS |

| Lansky et al[67] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 687 | 314 | 61.8 | 65.9 | < 0.0001 | 61.3 | 74.2 | < 0.0001 | 11.5 | 4.5 | 0.0002 |

| Tizón-Marcos et al[33] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 1050 | 298 | 59.7 | 62.5 | 58 | 65 | 0.066 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 0.066 | |

| Hirakawa et al[19] 2007 | Pros cohort | AMI | 2048 | 566 | 62.92 | 71.08 | < 0.01 | 60.1 | 56.0 | < 0.05 | 34.81 | 40.11 | < 0.05 |

| Mueller et al[55] 2002 | Pros cohort | MI | 1033 | 417 | 64 | 68 | 0.01 | 24 | 26 | 0.45 | 42 | 29 | 0.01 |

| Duvernoy et al[43] 2010 | Pros cohort | PCI | 14 848 | 7877 | 61.9 | 66.9 | < 0.001 | 49.4 | 55.0 | < 0.001 | 22.8 | 18.0 | < 0.001 |

| Liu et al[25] 2008 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 143 | 116 | 68.1 | 68.7 | 0.61 | 14.7 | 10.3 | 0.29 | 48.2 | 61.2 | 0.03 |

| Jibran et al[81] 2010 | Retro cohort | ACS + PCI | 331 | 137 | 60.7 | 66.1 | < 0.00001 | 41.1 | 48.9 | 0.3 | 22.7 | 12.4 | 0.3 |

| De Luca et al[41] 2004 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 1195 | 353 | 59 | 66 | < 0.001 | 47.9 | 43.8 | NS | 20.7 | 22.3 | NS |

| Bufe et al[62] 2010 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 376 | 124 | 58 | 65 | < 0.001 | 48.1 | 54.0 | 0.031 | 24.2 | 21.8 | 0.667 |

| Lawesson et al[24] 2010 | Retro cohort | STEMI aged < 46 | 1748 | 384 | 40.8 | 40.4 | 0.14 | 59.3 | 72.9 | < 0.001 | 33.6 | 19.2 | < 0.001 |

| Berger et al[10] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 2953 | 1331 | 61.9 | 66.8 | < 0.001 | 48 | 50 | 0.195 | 18 | 17 | NS |

| Toumpoulis et al[34] 2006 | Pros cohort | CABG | 2598 | 1162 | 63.2 | 66.2 | < 0.001 | 4.6 | 7.3 | 0.001 | 73.7 | 69.3 | 0.005 |

| Tillmanns et al[32] 2005 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 513 | 178 | 60 | 66 | < 0.0001 | 43 | 44 | NS | 571 | 561 | NS |

| Vakili et al[57] 2001 | Retro cohort | PTCA first MI | 727 | 317 | 59 | 65 | < 0.005 | 56 | 59 | NS | 15 | 12 | NS |

More than single vessel disease. MI: Myocardial infarction; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; STEMI: ST elevation MI; NS: Not significant.

The proportion of men and women undergoing CABG was equal[10,11,26,28,30-32,37,79] as shown in Table 4. In women undergoing CABG, the internal mammary artery was used less often than in men. The usage of this artery was associated with a decrease in mortality after CABG[16]. Furthermore, women underwent surgery more commonly on an urgent basis than men[12,16,20,34,36,63,75].

Table 4.

Percentage of performed revascularizations stratified by gender

| Author study/date | Design | Study population | Patients | Age (mean, yr) | P | CABG (%) | P | PCI (%) | P | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||||||

| Reynolds et al[30] 2007 | RCT | MI | 12 498 | 4090 | 59.5 | 67.0 | < 0.001 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 0.45 | 27.4 | 23.6 | < 0.01 |

| Matsui et al[26] 2002 | Retro cohort | AMI | 346 | 136 | 62.9 | 70.4 | 0.01 | 4 | 7 | 0.179 | 95 | 84 | 0.001 |

| Moriel et al[28] 2005 | Pros cohort | ACS | 820 | 511 | 78 | 79 | 0.12 | 7 | 6 | 0.47 | 32 | 28 | 0.06 |

| Herlitz et al[18] 2009 | Retro cohort | AMI | 835 | 588 | 72.7 | 79.2 | < 0.0001 | 9 | 2 | < 0.0001 | 15 | 7 | NS |

| Setoguchi et al[31] 2008 | Pros cohort | AMI | 317 | 1308 | 80 | 82 | < 0.001 | 3 | 3 | 0.73 | 10 | 12 | 0.40 |

| Tillmanns et al[32] 2005 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 513 | 178 | 60 | 66 | < 0.0001 | 3 | 2 | NS | 95.1 | 93.8 | |

| Toumpoulis et al[34] 2006 | Pros cohort | CABG | 2598 | 1162 | 63.2 | 66.2 | < 0.001 | 100 | 100 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.002 | |

| Berger et al[10] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 2953 | 1331 | 61.9 | 66.8 | < 0.001 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.179 | 100 | 100 | |

| Alfredsson et al[11] 2007 | Pros cohort | Unstable/NSTEMI | 34020 | 19761 | 69 | 73 | < 0.001 | 7 | 5 | 18 | 14 | ||

| Lagerqvist et al[21] 2001 | RCT | AMI | 1708 | 749 | 64 | 68 | < 0.001 | 30 | 24 | 34 | 28 | ||

| SoS[37] 2004 | RCT | Multivessel disease | 782 | 206 | 60.6 | 64.7 | < 0.001 | 50.1 | 52.4 | 49.9 | 47.6 | ||

| Singh et al[79] 2008 | Retro cohort | PCI | 7616 | 3365 | 64.7 | 69.4 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Liu et al[25] 2008 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 143 | 116 | 68.1 | 68.7 | 0.61 | 85.3 | 84.3 | NS | |||

MI: Myocardial infarction; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST elevation MI; NS: Not significant.

Prognosis

Many discrepancies existed between the different studies investigating the prognosis of men and women with an ACS. Some studies showed that women had more complications during hospital admission compared with men[7,9,13,18,22,30,36,53,61,64,78,80], while others showed no differences[23,25,28,33-35,38,40,44,46,48,54,56-58,62,81] (Table 5). Particularly at younger ages, women tended to have a greater risk for cardiac events compared with men at the same age[64,82]. This difference disappeared in patients older than 65 years[82,83].

Table 5.

Percentage of peri-procedural complications during index admission stratified by gender

| Author study/date | Design | Study population | Patients | Age (mean, yr) | P | Complications < admission (%) | P | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | ||||||

| Lansky et al[22] 2005 | RCT | AMI + PTCA | 1520 | 562 | 57.0 | 66.0 | < 0.001 | MACE | 3.2 | 6.4 | 0.002 |

| Bleeding | 2.0 | 5.2 | 0.0003 | ||||||||

| Lansky et al[67] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 687 | 314 | 61.8 | 65.9 | < 0.0001 | MACE1 | 1.3 | 3.2 | 0.0766 |

| Vascular1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6844 | ||||||||

| MI1 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 0.0526 | ||||||||

| Tizón-Marcos et al[33] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 1050 | 298 | 59.7 | 62.5 | < 0.0001 | MACE1 | 3.9 | 3.4 | 0.86 |

| Bleeding1 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.16 | ||||||||

| MI1 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Thompson et al[53] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 807 | 359 | 61.7 | 67.7 | < 0.0001 | MACE | 2.7 | 3.9 | 0.29 |

| Vascular | 4.2 | 12.0 | < 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Jibran et al[81] 2010 | Retro cohort | ACS + PCI | 331 | 137 | 60.7 | 66.1 | < 0.0001 | MACE1 | 3.9 | 2.9 | 0.8 |

| Access site1 | 1.5 | 6.2 | 0.02 | ||||||||

| MI1 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Duvernoy et al[43] 2010 | Pros cohort | PCI | 14 848 | 7877 | 61.9 | 66.9 | < 0.001 | MACE | 4.48 | 5.19 | < 0.001 |

| Vascular | 1.02 | 3.34 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| MI | 1.60 | 1.66 | 0.70 | ||||||||

| Bufe et al[62] 2010 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 376 | 124 | 58 | 65 | < 0.001 | Shock | 10.1 | 11.3 | 0.838 |

| Renal failure | 1.3 | 1.6 | 0.835 | ||||||||

| Reynolds et al[30] 2007 | RTC | MI | 12 498 | 4090 | 59.5 | 67.0 | < 0.001 | CVA1 | 0.2 | 0.6 | < 0.01 |

| Heart failure | 4.0 | 6.7 | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Re-MI | 2.7 | 3.5 | 0.004 | ||||||||

| Matsui et al[26] 2002 | Retro cohort | AMI | 346 | 136 | 62.9 | 70.4 | Heart failure | 16 | 26 | 0.013 | |

| Re-MI | 5 | 6 | 0.568 | ||||||||

| Moriel et al[28] 2005 | Pros cohort | ACS | 820 | 511 | 78 | 79 | 0.12 | CVA | 2 | 1 | 0.79 |

| Heart failure | 21 | 21 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| Re-MI | 15 | 14 | 0.61 | ||||||||

| Uva et al[35] 2009 | RCT | CABG | 1485 | 481 | 64.7 | 69.0 | 0.001 | MACE | 3.9 | 6.6 | NS |

| CVA | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.2 | ||||||||

| MI | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.08 | ||||||||

| Herlitz et al[18] 2009 | Retro cohort | AMI | 835 | 588 | 72.7 | 79.2 | < 0.0001 | Re-MI | 4 | 2 | 0.02 |

| Toumpoulis et al[34] 2006 | Pros cohort | CABG | 2598 | 1162 | 63.2 | 66.2 | < 0.001 | CVA | 2.8 | 4.2 | NS |

| Bleeding | 1.8 | 1.5 | 0.592 | ||||||||

| MI | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.657 | ||||||||

| Liu et al[25] 2008 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 143 | 116 | 68.1 | 68.7 | 0.61 | MACE | 4.2 | 6.0 | 0.50 |

| Berger et al[10] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 2953 | 1331 | 61.9 | 66.8 | < 0.001 | MACE | 2.9 | 3.0 | 0.922 |

| CVA | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.905 | ||||||||

| MI | 1.6 | 1.7 | NS | ||||||||

| Access site | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.018 | ||||||||

| Chiu et al[13] 2004 | Pros cohort | PCI | 12 738 | 5301 | 62.3 | 66.5 | < 0.001 | Transfusion | 4 | 12 | < 0.001 |

| Haematoma | 5 | 6 | 0.568 | ||||||||

| Setoguchi et al[31] 2008 | Pros cohort | AMI | 317 | 1308 | 80 | 82 | < 0.001 | CVA | 3 | 4 | 0.57 |

| Singh et al[79] 2008 | Retro cohort | PCI | 7616 | 3365 | 64.7 | 69.4 | 0.48 | CVA | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.29 |

| MI | 1.1 | 1.4 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Tillmanns et al[32] 2005 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 513 | 178 | 60 | 66 | < 0.0001 | Re-MI | 3 | 2 | NS |

After 30 d. MI: Myocardial infarction; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST elevation MI; NS: Not significant; CVA: Cerebrovascular accident; MACE: Major adverse cardiac events.

Many discrepancies existed in the short-term mortality rate of patients with ACS. Some studies revealed a higher short-term mortality risk among women[7,12,17,22,24,27,28,35,36,57,64,78], while others did not[9-11,16,18,26,32-34,46,48,54,59,65,81] (Table 6). As discussed above, older age at presentation was an important confounding factor in this regard[29,39,54,58,75,77,84].

Table 6.

Mortality rates in male and female patients with coronary artery disease at admission, at thirty days and after one-year of follow-up

| Author study/date | Design | Study population | Patients | Age (mean, yr) | P | Mortality < admission (%) | P | Mortality < 30 d (%) | P | Mortality < 1 year (%) | P | |||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||

| Lansky et al[22] 2005 | RCT | AMI + PTCA | 1520 | 562 | 57.0 | 66.0 | < 0.001 | 1.0 | 3.4 | 0.0003 | 1.1 | 4.6 | < 0.001 | 3.0 | 7.6 | < 0.001 |

| Singh et al[79] 2008 | Retro cohort | PCI | 7616 | 3365 | 64.7 | 69.4 | 0.48 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 0.38 | 2 | 3 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 0.490 |

| Alfredsson et al[11] 2007 | Pros cohort | Unstable/NSTEMI | 34 020 | 19 761 | 69 | 73 | < 0.001 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 19 | |||

| Setoguchi et al[31] 2008 | Pros cohort | AMI | 317 | 1308 | 80 | 82 | < 0.001 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 9.8 | 8.6 | 21.5 | 18.2 | |||

| 24.33 | 25.03 | |||||||||||||||

| Matsui et al[26] 2002 | RCT | MI | 346 | 136 | 62.9 | 70.4 | 4 | 4 | 0.851 | 4 | 10 | 0.013 | ||||

| Uva et al[35] 2009 | RCT | CABG | 1485 | 481 | 64.7 | 69.0 | 0.001 | 0.8 | 2 | 0.01 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 0.09 | |||

| Toumpoulis et al[34] 2006 | Pros cohort | CABG | 2598 | 1162 | 63.2 | 66.2 | < 0.001 | 2.7 | 2.9 | 0.639 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 0.747 | |||

| Moriel et al[28] 2005 | Pros cohort | ACS | 820 | 511 | 78 | 79 | 0.12 | 7 | 12 | 0.007 | 191 | 211 | 0.480 | |||

| Herlitz et al[18] 2009 | Retro cohort | AMI | 835 | 588 | 72.7 | 79.2 | < 0.0001 | 12 | 14 | NS | 18 | 22 | 0.040 | |||

| Lawesson et al[24] 2010 | Retro cohort | STEMI aged < 46 | 1748 | 384 | 40.8 | 40.4 | 0.14 | 1.0 | 2.9 | 0.005 | 2.2 | 3.7 | 0.010 | |||

| Berger et al[10] 2006 | Pros cohort | PCI | 2953 | 1331 | 61.9 | 66.8 | < 0.001 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.918 | 8.92 | 102 | 0.197 | |||

| Liu et al[25] 2008 | Pros cohort | STEMI + PCI | 143 | 116 | 68.1 | 68.7 | 0.61 | 2.8 | 5.2 | 0 | 3.4 | |||||

| Anand et al[9] 2005 | Trial | ACS | 7726 | 4836 | 62.7 | 66.5 | 0.0001 | 4.9 | 4.4 | 0.235 | 11.1 | 9.7 | 0.040 | |||

| Tizón-Marcos et al[33] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 1050 | 298 | 59.7 | 62.5 | < 0.0001 | 0.2 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.720 | |||

| Tillmanns et al[32] 2005 | Pros cohort | STEMI | 513 | 178 | 60 | 66 | < 0.0001 | 6 | 6.2 | NS | 9 | 12.5 | 0.600 | |||

| 122 | 182 | 0.070 | ||||||||||||||

| Lansky et al[67] 2009 | RCT | PCI | 687 | 314 | 61.8 | 65.9 | < 0.0001 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 0.447 | ||||

| Koch et al[20] 2003 | Pros cohort | CABG | 1588 | 460 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 0.29 | 4.21 | 7.11 | 0.020 | ||||||

| 15.84 | 19.64 | 0.030 | ||||||||||||||

| Lagerqvist et al[21] 2001 | RCT | AMI | 1708 | 749 | 64 | 68 | < 0.001 | 5.7 | 7.2 | NS | ||||||

| Chiu et al[13] 2004 | Pros cohort | PCI | 12 738 | 5301 | 62.3 | 66.5 | < 0.001 | 5 | 7 | < 0.001 | ||||||

After 6 mo;

After 3 years;

After 4 years;

After 5 years;

Adjusted for age, diabetes, smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, increased cardiac enzymes, region and received therapy. MI: Myocardial infarction; CABG: Coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI: Percutaneous coronary intervention; ACS: Acute coronary syndrome; STEMI: ST elevation MI; NS: Not significant.

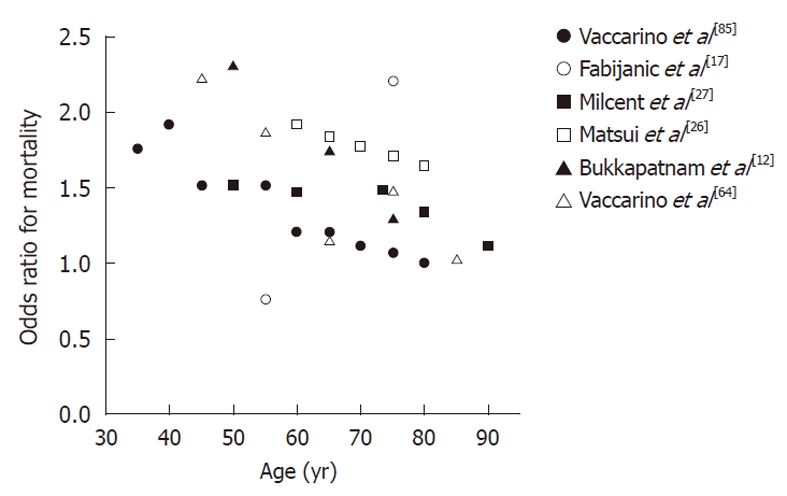

An important finding was that women with ACS had an increased mortality risk at younger ages compared with men of the same age[39,45,52,64]. Figure 1 illustrates the gender differences in mortality after a MI among different age categories. As shown in this Figure, the difference in mortality risk was reduced in older age[12,26,27,64,83,85].

Figure 1.

Gender differences in mortality after a myocardial infarction among different age categories. An odds ratio higher than one indicates an increased mortality after a myocardial infarction in women in comparison to men.

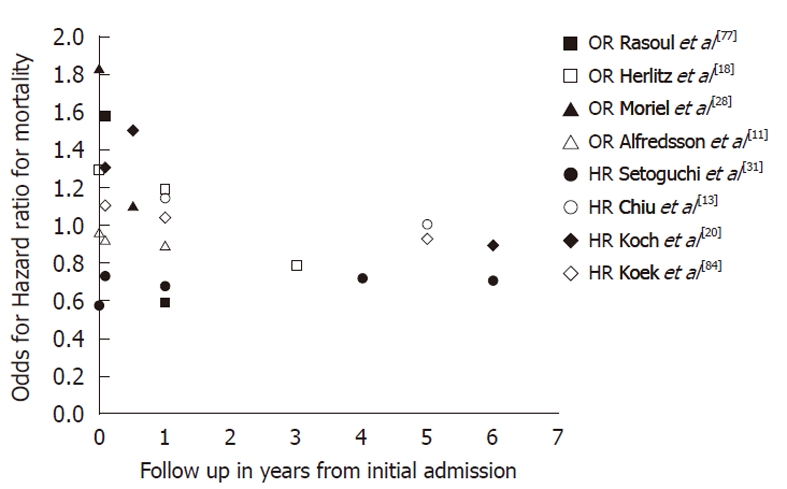

Independent predictors of mortality were old age[20,29,39-41,49,50,54,59,75,77,84], with an OR of 1.06 (95% CI: 1.05-1.07) for each additional year[40,74], diabetes[20,24,29,49,54,62,74,77,84], heart failure[20,29,39], CAD[29], duration of ischemia, multiple vessel disease, history of MI, hypertension[41,77], CVA[77], anemia[20], cardiogenic shock, peripheral vascular disease[39], and ST-elevation[74]. Whether female gender can be considered as an independent risk factor remains unclear. Some studies claimed it could[24,27,51,55,57,75,77], but others showed no significant association after adjustment for risk factors[16,22,29,34,38-40,42-46,49,50,53,54,58,59,61,62,66,80,82,84]. After adjustment for several risk factors, female gender persisted as a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in ACS only for patients aged 51-60 years (OR, 1.78; 95% CI: 1.04-3.04)[74]. After adjustment for age and cardiovascular risk factors, the long-term mortality rate was equal for both men and women[13,20,22-24,29,31,32,40,41,44-46,48,49,58-60,62,65,79] or even in favor of women[10,31,34,42,54,55,63,77,84], as shown in Table 6 and Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Gender differences in mortality risk in patients with coronary artery disease. An odds/hazard ratio higher than one indicates an increased mortality in women in comparison to men. OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio.

In the past 20-25 years the mortality rate at 30 d after PCI or CABG has declined equally in both men and women[76,79]. Data were inconsistent on the differences between men and women in the number of readmissions[86-88] and the number of second PCIs[10,18,21,23-26,28,33,35]. Interestingly, differences were found in the restenosis rates after PCI. In the first 6 mo after coronary stenting, restenosis was found in 28.9% of the women, compared with 33.9% of men (P = 0.01)[60,89]. After adjustment of gender, age and multiple risk factors, women showed a 23% risk reduction in angiographic restenosis compared with men (OR, 0.77; 95% CI: 0.63-0.93). Diabetes and small vessel size were identified as the most important predictors of restenosis. However, despite the higher prevalence of diabetes in women and smaller vessel size, women tended to have a lower incidence of restenosis[89]. Whether this can be explained by the protective mechanism of estrogens in women is still unknown. Estrogens were shown to have an antiinflammatory effect on the vessel wall and induce vasodilatation in coronary arteries[1]. However HRT in post-menopausal women did not lower the risk of mortality from CVD after adjustment for other risk factors[90-92]. HRT is therefore not recommended as primary or secondary prevention of CVD in women[73].

DISCUSSION

Women with CVD tended to have more cardiovascular risk factors such as diabetes, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia when presenting with ACS. More importantly, women with an ACS at a young age had a higher mortality rate during index hospitalization and during 30 d of follow-up compared with men[24]. A possible explanation could be that pre-menopausal women enjoyed some protection against ACS from estrogens and those women who developed ACS despite this hormonal protection were more likely to have a higher cardiovascular risk factor burden leading to a more severe clinical presentation and worse outcome. None of the discussed studies adjusted for the use of hormone therapy among women. This might lead to information bias, because hormone therapy could influence the outcome of women with ACS. In the elderly, the long-term mortality rate was equal for both men and women, and even slightly in favor of women[13,20,22-24,29,31,32,79]. This small advantage in survival might possibly be due to the greater awareness and control of hypertension in women, compared with men, as hypertension is an important risk factor for CVD[72].

Study results were inconsistent, but it seems that an angiogram was less often performed in women than in men. This phenomenon could partly be explained by the higher average age of women as fewer diagnostic CAG were performed in both male and female patients of older age. However, where a CAG was performed, women and men received the same therapy for similar vessel disease[9,11,18,24,28,30]. No differences between genders were found in the number of performed CABGs.

The current review has several limitations. Most included studies were retrospective in nature and performed a post hoc analysis by stratifying by gender. Included studies were hard to compare due to different patient characteristics; some studies included patients with STEMI, while others also included non-STEMI or patients with unstable angina. Another important limitation is the large difference in mean age between the included men and women across the different studies. Consequently, a comparison between the two genders was very difficult and no firm conclusion can be drawn. In addition, women are still underrepresented in most studies (inclusion rate < 30%). Due to the relatively low incidence of outcomes (e.g. complications, death), greater statistical power is needed to reach statistical significance. Therefore, large prospective observational cohort studies are needed in the future to provide sufficient power to answer the question whether female gender is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

CVD is the main cause of death among women. The prevalence of CVD is higher among men, but this gap narrows after the menopause. Women present approximately 10 years later with ACS than men, and at the time of presentation have a higher cardiovascular risk factor burden. Women are less often assigned to receive a CAG and subsequently less PCIs are performed. In addition, women have more complications and a higher short-term mortality after revascularization. Finally, mortality rates are higher among young women with ACS, but this difference tends to disappear with age, and long-term prognosis is even better among older women during long-term follow-up.

COMMENTS

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the main cause of death among women and its occurrence narrows women’s survival advantage over men. Many studies investigated gender differences in CVD, but results were inconsistent due to several limitations. Women were generally underrepresented in mainly retrospective studies and a true comparison between genders was difficult due to large differences in age at presentation between the included men and women.

Research frontiers

It is important to clarify possible differences between men and women in a large prospective cohort study, with equal numbers of male and female patients. Furthermore, as age is an important confounding factor, men and women of similar age should be compared. A systematic literature search was performed to assess the current state of knowledge on possible gender differences in CVD.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In the short-term, women with CVD seem to have a worse outcome compared with men. In particular, young women have an increased mortality risk, but this disadvantage disappears at older age. Moreover, long-term mortality is slightly better in elderly women compared with men.

Peer review

This is an interesting meta-analysis on putative gender differences in cardiovascular care.

Footnotes

Supported by A clinical fellowship from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development to Folkert W Asselbergs, No. 90700342

Peer reviewers: Paul Erne, MD, Professor, Head, Department of Cardiology, Luzerner Kantonsspital, CH-6000 Luzern 16, Switzerland; Pietro A Modesti, MD, PhD, Professor of Internal Medicine, Department Critical Care Medicine, University of Florence, Viale Morgagni 85, 50124 Florence, Italy

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010;18:598–603. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pilote L, Dasgupta K, Guru V, Humphries KH, McGrath J, Norris C, Rabi D, Tremblay J, Alamian A, Barnett T, et al. A comprehensive view of sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. CMAJ. 2007;176:S1–S44. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quyyumi AA. Women and ischemic heart disease: pathophysiologic implications from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Study and future research steps. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:S66–S71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alexander KP, Peterson ED. Medical and surgical management of coronary artery disease in women. Am J Manag Care. 2001;7:951–956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–952. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, Weaver WD, White HD, Van de Werf F, Aylward P, Topol EJ, Califf RM. Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global Use of Strategies to Open Occluded Coronary Arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes IIb Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:226–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199907223410402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosengren A, Wallentin L, K Gitt A, Behar S, Battler A, Hasdai D. Sex, age, and clinical presentation of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand SS, Xie CC, Mehta S, Franzosi MG, Joyner C, Chrolavicius S, Fox KA, Yusuf S. Differences in the management and prognosis of women and men who suffer from acute coronary syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1845–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger JS, Sanborn TA, Sherman W, Brown DL. Influence of sex on in-hospital outcomes and long-term survival after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2006;151:1026–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alfredsson J, Stenestrand U, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Gender differences in management and outcome in non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2007;93:1357–1362. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.102012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bukkapatnam RN, Yeo KK, Li Z, Amsterdam EA. Operative mortality in women and men undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (from the California Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Outcomes Reporting Program) Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:339–342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiu JH, Bhatt DL, Ziada KM, Chew DP, Whitlow PL, Lincoff AM, Ellis SG, Topol EJ. Impact of female sex on outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2004;148:998–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clayton TC, Pocock SJ, Henderson RA, Poole-Wilson PA, Shaw TR, Knight R, Fox KA. Do men benefit more than women from an interventional strategy in patients with unstable angina or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction? The impact of gender in the RITA 3 trial. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1641–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dallongevillle J, De Bacquer D, Heidrich J, De Backer G, Prugger C, Kotseva K, Montaye M, Amouyel P. Gender differences in the implementation of cardiovascular prevention measures after an acute coronary event. Heart. 2010;96:1744–1749. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.196170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ennker IC, Albert A, Pietrowski D, Bauer K, Ennker J, Florath I. Impact of gender on outcome after coronary artery bypass surgery. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2009;17:253–258. doi: 10.1177/0218492309104746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabijanic D, Culic V, Bozic I, Miric D, Stipic SS, Radic M, Vucinovic Z. Gender differences in in-hospital mortality and mechanisms of death after the first acute myocardial infarction. Ann Saudi Med. 2006;26:455–460. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2006.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herlitz J, Dellborg M, Karlsson T, Evander MH, Hartford M, Perers E, Caidahl K. Treatment and outcome in acute myocardial infarction in a community in relation to gender. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirakawa Y, Masuda Y, Kuzuya M, Iguchi A, Kimata T, Uemura K. Impact of gender on in-hospital mortality of patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: an evaluation of the TAMIS-II data. Intern Med. 2007;46:363–366. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.46.6137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koch CG, Weng YS, Zhou SX, Savino JS, Mathew JP, Hsu PH, Saidman LJ, Mangano DT. Prevalence of risk factors, and not gender per se, determines short- and long-term survival after coronary artery bypass surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2003;17:585–593. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(03)00201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lagerqvist B, Säfström K, Ståhle E, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Is early invasive treatment of unstable coronary artery disease equally effective for both women and men? FRISC II Study Group Investigators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lansky AJ, Pietras C, Costa RA, Tsuchiya Y, Brodie BR, Cox DA, Aymong ED, Stuckey TD, Garcia E, Tcheng JE, et al. Gender differences in outcomes after primary angioplasty versus primary stenting with and without abciximab for acute myocardial infarction: results of the Controlled Abciximab and Device Investigation to Lower Late Angioplasty Complications (CADILLAC) trial. Circulation. 2005;111:1611–1618. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000160362.55803.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Cristea E, Parise H, Feit F, Ohman EM, White HD, Alexander KP, Bertrand ME, Desmet W, et al. Impact of gender and antithrombin strategy on early and late clinical outcomes in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (from the ACUITY trial) Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:1196–1203. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lawesson SS, Stenestrand U, Lagerqvist B, Wallentin L, Swahn E. Gender perspective on risk factors, coronary lesions and long-term outcome in young patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Heart. 2010;96:453–459. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.175463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Wang LF, Yang XF, Ge YG, Wang HG, Xu L, Li WM, Ni ZH, Xia K, Chi YH, et al. Gender differences in efficacy of primary percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121:2374–2378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsui K, Fukui T, Hira K, Sobashima A, Okamatsu S, Hayashida N, Tanaka S, Nobuyoshi M. Impact of sex and its interaction with age on the management of and outcome for patients with acute myocardial infarction in 4 Japanese hospitals. Am Heart J. 2002;144:101–107. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milcent C, Dormont B, Durand-Zaleski I, Steg PG. Gender differences in hospital mortality and use of percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: microsimulation analysis of the 1999 nationwide French hospitals database. Circulation. 2007;115:833–839. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.664979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moriel M, Behar S, Tzivoni D, Hod H, Boyko V, Gottlieb S. Management and outcomes of elderly women and men with acute coronary syndromes in 2000 and 2002. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1521–1526. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.13.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pearte CA, Furberg CD, O’Meara ES, Psaty BM, Kuller L, Powe NR, Manolio T. Characteristics and baseline clinical predictors of future fatal versus nonfatal coronary heart disease events in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Circulation. 2006;113:2177–2185. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.610352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reynolds HR, Farkouh ME, Lincoff AM, Hsu A, Swahn E, Sadowski ZP, White JA, Topol EJ, Hochman JS. Impact of female sex on death and bleeding after fibrinolytic treatment of myocardial infarction in GUSTO V. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2054–2060. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Levin R, Winkelmayer WC. Gender differences in the management and prognosis of myocardial infarction among patients & gt; or = 65 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1531–1536. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tillmanns H, Waas W, Voss R, Grempels E, Hölschermann H, Haberbosch W, Waldecker B. Gender differences in the outcome of cardiac interventions. Herz. 2005;30:375–389. doi: 10.1007/s00059-005-2716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tizón-Marcos H, Bertrand OF, Rodés-Cabau J, Larose E, Gaudreault V, Bagur R, Gleeton O, Courtis J, Roy L, Poirier P, Costerousse O, De Larochellière R. Impact of female gender and transradial coronary stenting with maximal antiplatelet therapy on bleeding and ischemic outcomes. Am Heart J. 2009;157:740–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toumpoulis IK, Anagnostopoulos CE, Balaram SK, Rokkas CK, Swistel DG, Ashton RC, DeRose JJ. Assessment of independent predictors for long-term mortality between women and men after coronary artery bypass grafting: are women different from men? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Uva MS, Freitas S, Pedro A, Matias F, Mesquita A, Bau J, Pinho J, Fernandes J, Magalhães MP. Off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery in women. Rev Port Cardiol. 2009;28:813–824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Woods SE, Noble G, Smith JM, Hasselfeld K. The influence of gender in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: an eight-year prospective hospitalized cohort study. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:428–434. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Z, Weintraub WS, Mahoney EM, Spertus JA, Booth J, Nugara F, Stables RH, Vaccarino V. Relative benefit of coronary artery bypass grafting versus stent-assisted percutaneous coronary intervention for angina pectoris and multivessel coronary disease in women versus men (one-year results from the Stent or Surgery trial) Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:404–409. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G, Migliorini A, Trapani M, Santoro GM, Bolognese L, Dovellini EV. Sex-based differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes after primary angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87:289–293. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berger JS, Brown DL. Gender-age interaction in early mortality following primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1140–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrabba N, Santoro GM, Balzi D, Barchielli A, Marchionni N, Fabiani P, Landini C, Scarti L, Santoro G, Valente S, et al. In-hospital management and outcome in women with acute myocardial infarction (data from the AMI-Florence Registry) Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:1118–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Dambrink JH, Ottervanger JP, van ‘t Hof AW, Zijlstra F, Hoorntje JC, Gosselink AT, de Boer MJ. Sex-related differences in outcome after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty: data from the Zwolle Myocardial Infarction study. Am Heart J. 2004;148:852–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De Luca G, Gibson CM, Gyöngyösi M, Zeymer U, Dudek D, Arntz HR, Bellandi F, Maioli M, Noc M, Zorman S, et al. Gender-related differences in outcome after ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty and glycoprotein IIb-IIIa inhibitors: insights from the EGYPT cooperation. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2010;30:342–346. doi: 10.1007/s11239-010-0451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duvernoy CS, Smith DE, Manohar P, Schaefer A, Kline-Rogers E, Share D, McNamara R, Gurm HS, Moscucci M. Gender differences in adverse outcomes after contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention: an analysis from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) percutaneous coronary intervention registry. Am Heart J. 2010;159:677–683.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halvorsen S, Eritsland J, Abdelnoor M, Holst Hansen C, Risøe C, Midtbø K, Bjørnerheim R, Mangschau A. Gender differences in management and outcome of acute myocardial infarctions treated in 2006-2007. Cardiology. 2009;114:83–88. doi: 10.1159/000216582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heer T, Schiele R, Schneider S, Gitt AK, Wienbergen H, Gottwik M, Gieseler U, Voigtländer T, Hauptmann KE, Wagner S, et al. Gender differences in acute myocardial infarction in the era of reperfusion (the MITRA registry) Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:511–517. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02289-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jankowski P, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, Czarnecka D, Bryniarski L, Brzozowska-Kiszka M, Kieć-Wilk B, Dymek G, Kopacz E, Królikowski T, Dudek D. Gender does not influence event-free survival in patients with ischaemic heart disease undergoing non-emergency coronary angiography. A single centre analysis. Kardiol Pol. 2007;65:475–484; discussion 485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jneid H, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Hernandez AF, Palacios IF, Maree AO, Wells Q, Bozkurt B, Labresh KA, Liang L, et al. Sex differences in medical care and early death after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2008;118:2803–2810. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.789800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kralev S, Hennig O, Lang S, Kälsch T, Borggrefe M, Dempfle CE, Süselbeck T. Sex-based differences in clinical and angiographic outcomes in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with concomitant use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. Cardiol J. 2010;17:580–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee LC, Poh KK, Tang TP, Tan YL, Tee HW, Tan HC. The impact of gender on the outcomes of invasive versus conservative management of patients with non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park JS, Kim YJ, Shin DG, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Chung WS, Seung KB, Kim CJ, Cho MC, Jang YS, et al. Gender differences in clinical features and in-hospital outcomes in ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction: from the Korean Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry (KAMIR) study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:E1–E6. doi: 10.1002/clc.20557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reina A, Colmenero M, Aguayo de Hoyos E, Arós F, Martí H, Claramonte R, Cuñat J. Gender differences in management and outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2007;116:389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Srinivas VS, Garg S, Negassa A, Bang JY, Monrad ES. Persistent sex difference in hospital outcome following percutaneous coronary intervention: results from the New York State reporting system. J Invasive Cardiol. 2007;19:265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thompson CA, Kaplan AV, Friedman BJ, Jayne JE, Gerling BR, Niles NW, Hettleman BD, Robb JF. Gender-based differences of percutaneous coronary intervention in the drug-eluting stent era. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;67:25–31. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Dirschinger J, Pache J, Seyfarth M, Blasini R, Hall D, Neumann FJ, Schömig A. Sex-based analysis of outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated predominantly with percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA. 2002;287:210–215. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mueller C, Neumann FJ, Roskamm H, Buser P, Hodgson JM, Perruchoud AP, Buettner HJ. Women do have an improved long-term outcome after non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes treated very early and predominantly with percutaneous coronary intervention: a prospective study in 1,450 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Trabattoni D, Bartorelli AL, Montorsi P, Fabbiocchi F, Loaldi A, Galli S, Ravagnani P, Cozzi S, Grancini L, Liverani A, et al. Comparison of outcomes in women and men treated with coronary stent implantation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2003;58:20–28. doi: 10.1002/ccd.10372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vakili BA, Kaplan RC, Brown DL. Sex-based differences in early mortality of patients undergoing primary angioplasty for first acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2001;104:3034–3038. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.101060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heer T, Gitt AK, Juenger C, Schiele R, Wienbergen H, Towae F, Gottwitz M, Zahn R, Zeymer U, Senges J. Gender differences in acute non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:160–166. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantor WJ, Miller JM, Hellkamp AS, Kramer JM, Peterson ED, Hasselblad V, Zidar JP, Newby LK, Ohman EM. Role of target vessel size and body surface area on outcomes after percutaneous coronary interventions in women. Am Heart J. 2002;144:297–302. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chang WC, Kaul P, Westerhout CM, Graham MM, Fu Y, Chowdhury T, Armstrong PW. Impact of sex on long-term mortality from acute myocardial infarction vs unstable angina. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2476–2484. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.20.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheng CI, Yeh KH, Chang HW, Yu TH, Chen YH, Chai HT, Yip HK. Comparison of baseline characteristics, clinical features, angiographic results, and early outcomes in men vs women with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention. Chest. 2004;126:47–53. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bufe A, Wolfertz J, Dinh W, Bansemir L, Koehler T, Haltern G, Guelker H, Füth R, Scheffold T, Lankisch M. Gender-based differences in long-term outcome after ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:471–475. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guru V, Fremes SE, Austin PC, Blackstone EH, Tu JV. Gender differences in outcomes after hospital discharge from coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2006;113:507–516. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.576652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vaccarino V, Abramson JL, Veledar E, Weintraub WS. Sex differences in hospital mortality after coronary artery bypass surgery: evidence for a higher mortality in younger women. Circulation. 2002;105:1176–1181. doi: 10.1161/hc1002.105133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lansky AJ, Mehran R, Dangas G, Cristea E, Shirai K, Costa R, Costantini C, Tsuchiya Y, Carlier S, Mintz G, et al. Comparison of differences in outcome after percutaneous coronary intervention in men versus women & lt; 40 years of age. Am J Cardiol. 2004;93:916–919. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woods SE, Chandran P, Levin L. Does the patient’s sex influence cardiovascular outcome after acute myocardial infarction? J Fam Pract. 2002;51:237–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lansky AJ, Ng VG, Mutlu H, Cristea E, Guiran JB, Midei M, Newman W, Sanz M, Sood P, Doostzadeh J, et al. Gender-based evaluation of the XIENCE V everolimus-eluting coronary stent system: clinical and angiographic results from the SPIRIT III randomized trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;74:719–727. doi: 10.1002/ccd.22067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prescott E, Hippe M, Schnohr P, Hein HO, Vestbo J. Smoking and risk of myocardial infarction in women and men: longitudinal population study. BMJ. 1998;316:1043–1047. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7137.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Huxley R, Barzi F, Woodward M. Excess risk of fatal coronary heart disease associated with diabetes in men and women: meta-analysis of 37 prospective cohort studies. BMJ. 2006;332:73–78. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38678.389583.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chua TP, Saia F, Bhardwaj V, Wright C, Clarke D, Hennessy M, Fox KM. Are there gender differences in patients presenting with unstable angina? Int J Cardiol. 2000;72:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(99)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw LJ, Shaw RE, Merz CN, Brindis RG, Klein LW, Nallamothu B, Douglas PS, Krone RJ, McKay CR, Block PC, et al. Impact of ethnicity and gender differences on angiographic coronary artery disease prevalence and in-hospital mortality in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry. Circulation. 2008;117:1787–1801. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.726562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pereira M, Lunet N, Azevedo A, Barros H. Differences in prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of hypertension between developing and developed countries. J Hypertens. 2009;27:963–975. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e3283282f65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, Newby LK, Piña IL, Roger VL, Shaw LJ, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women--2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1404–1423. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Radovanovic D, Erne P, Urban P, Bertel O, Rickli H, Gaspoz JM. Gender differences in management and outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results on 20,290 patients from the AMIS Plus Registry. Heart. 2007;93:1369–1375. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blankstein R, Ward RP, Arnsdorf M, Jones B, Lou YB, Pine M. Female gender is an independent predictor of operative mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery: contemporary analysis of 31 Midwestern hospitals. Circulation. 2005;112:I323–I327. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Humphries KH, Gao M, Pu A, Lichtenstein S, Thompson CR. Significant improvement in short-term mortality in women undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (1991 to 2004) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:1552–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rasoul S, Ottervanger JP, de Boer MJ, Dambrink JH, Hoorntje JC, Marcel Gosselink AT, Zijlstra F, Suryapranata H, van ‘t Hof AW. Predictors of 30-day and 1-year mortality after primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Coron Artery Dis. 2009;20:415–421. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e32832e5c4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lee KH, Jeong MH, Ahn YK, Kim JH, Chae SC, Kim YJ, Hur SH, Seong IW, Hong TJ, Choi D, et al. Gender differences of success rate of percutaneous coronary intervention and short term cardiac events in Korea Acute Myocardial Infarction Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2008;130:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singh M, Rihal CS, Gersh BJ, Roger VL, Bell MR, Lennon RJ, Lerman A, Holmes DR. Mortality differences between men and women after percutaneous coronary interventions. A 25-year, single-center experience. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:2313–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Akhter N, Milford-Beland S, Roe MT, Piana RN, Kao J, Shroff A. Gender differences among patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the American College of Cardiology-National Cardiovascular Data Registry (ACC-NCDR) Am Heart J. 2009;157:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jibran R, Khan JA, Hoye A. Gender disparity in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention for acute coronary syndromes - does it still exist in contemporary practice? Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cartier R, Bouchot O, El-Hamamsy I. Influence of sex and age on long-term survival in systematic off-pump coronary artery bypass surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;34:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Glaser R, Selzer F, Jacobs AK, Laskey WK, Kelsey SF, Holper EM, Cohen HA, Abbott JD, Wilensky RL. Effect of gender on prognosis following percutaneous coronary intervention for stable angina pectoris and acute coronary syndromes. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:1446–1450. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Koek HL, de Bruin A, Gast F, Gevers E, Kardaun JW, Reitsma JB, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. Short- and long-term prognosis after acute myocardial infarction in men versus women. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:993–999. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vaccarino V, Krumholz HM, Yarzebski J, Gore JM, Goldberg RJ. Sex differences in 2-year mortality after hospital discharge for myocardial infarction. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:173–181. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-3-200102060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hannan EL, Racz MJ, Walford G, Ryan TJ, Isom OW, Bennett E, Jones RH. Predictors of readmission for complications of coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA. 2003;290:773–780. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stewart RD, Campos CT, Jennings B, Lollis SS, Levitsky S, Lahey SJ. Predictors of 30-day hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2000;70:169–174. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)01386-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Steuer J, Blomqvist P, Granath F, Rydh B, Ekbom A, de Faire U, Ståhle E. Hospital readmission after coronary artery bypass grafting: are women doing worse? Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73:1380–1386. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03467-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mehilli J, Kastrati A, Bollwein H, Dibra A, Schühlen H, Dirschinger J, Schömig A. Gender and restenosis after coronary artery stenting. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hulley S, Grady D, Bush T, Furberg C, Herrington D, Riggs B, Vittinghoff E. Randomized trial of estrogen plus progestin for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in postmenopausal women. Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study (HERS) Research Group. JAMA. 1998;280:605–613. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.7.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, Blumenthal R, Davidson M, Hlatky M, Hsia J, Hulley S, Herd A, Khan S, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) JAMA. 2002;288:49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hsia J, Langer RD, Manson JE, Kuller L, Johnson KC, Hendrix SL, Pettinger M, Heckbert SR, Greep N, Crawford S, et al. Conjugated equine estrogens and coronary heart disease: the Women’s Health Initiative. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:357–365. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]