Abstract

Summary: The deluge of data emerging from high-throughput sequencing technologies poses large analytical challenges when testing for association to disease. We introduce a scalable framework for variable selection, implemented in C++ and OpenCL, that fits regularized regression across multiple Graphics Processing Units. Open source code and documentation can be found at a Google Code repository under the URL http://bioinformatics.oxfordjournals.org/content/early/2012/01/10/bioinformatics.bts015.abstract.

Contact: gary.k.chen@usc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

As the cost of sequencing continues to drop exponentially, it will soon be practical to test all variation in the genome for association to disease using data from thousands of individuals. There are obvious computational challenges in analyzing datasets on this scale. Regularized regression methods such as the LASSO (Tibshirani, 1996) and other extensions are appropriate tools for selecting important variables in problems where variables far exceed observations. Programs like glmnet (Friedman et al., 2010) are computationally efficient for small to moderately sized datasets, but do not scale to extremely large datasets due to memory burden. We introduce an object-oriented framework that scales across nodes on Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) clusters yet shields users from the underlying complexities of a distributed optimization algorithm, allowing them to easily implement custom Monte Carlo routines (e.g. permutation testing, bootstrapping, etc.). Practical use of our framework is demonstrated by an application to real and simulated data.

2 IMPLEMENTATION

Our C++ framework, named gpu-lasso, implements the mixed L1 and L2 penalized regression model of Zhou et al. (2010) on datasets with any arbitrary number of variables. L1 penalties enforce sparsity, whereas L2 penalties enable correlated predictors within groups (e.g. genes, pathways) to enter the model as well. gpu-lasso exploits the optimization scheme of greedy coordinate descent (GCD) which, upon estimating regression coefficients across all variables, updates the single variable leading to the greatest improvement to the likelihood with its new coefficient. In general, this requires more iterations to converge than cyclic coordinate descent (CCD), which updates each regression coefficient as it cycles through variables. However, this disadvantage diminishes for sparser models. More importantly, GCD exposes parallelism across subjects and variables, which makes it both a better fit for GPU processors and a more scalable algorithm compared CCD with, which only exposes parallelization at the subject level. Since GPU memory is far more limited than host memory, for larger datasets such as whole-genome sequence data it is essential to coordinate optimization across two or more GPUs. MPI routines in our framework handle this coordination, enabling GPUs to be distributed across a network. Our GPU kernels are implemented in OpenCL, which assure maximum portability across either ATI or nVidia GPU devices.

We compared runtime behavior of our program across multiple configurations and to glmnet (Friedman et al., 2010). We were also interested in scalability properties as optimization is split across nodes. Our host was configured with a pair of nVidia Tesla C2050s, 24 Xeon X5650 cores, and 48 GB of RAM. We generated datasets of various sizes by extracting genotypes from the first 250 000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and 1 million SNPs (ordered by position) of a large Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) (see Section 3). Table 1 shows that due to its implementation in the R environment, glmnet has a much heftier memory requirement than our C++ implementation and could not load the 1 million SNP dataset. Execution times were similar between glmnet and gpu-lasso, where gpu-lasso was slightly faster. Memory and runtime halved as expected when distributing across two nodes.

Table 1.

Computational requirements

| Method | Time per iteration (min : s) | Memory per node |

|---|---|---|

| 250 000 variables | ||

| glmnet | 2 : 20 | 46 GB |

| gpu-lasso (1 CPU) | 0 : 54 | 415 MB |

| gpu-lasso (1 GPU) | 0 : 1.85 | 415 MB |

| gpu-lasso (2 GPU) | 0 : 0.93 | 208 MB |

| 1 million variables | ||

| glmnet | NA | NA |

| gpu-lasso (1 CPU) | 3 : 47 | 1.7 GB |

| gpu-lasso (1 GPU) | 0 : 7.7 | 1.7 GB |

| gpu-lasso (2 GPU) | 0 : 3.8 | 863 MB |

A total of 7000 subjects in all analyses.

3 APPLICATION

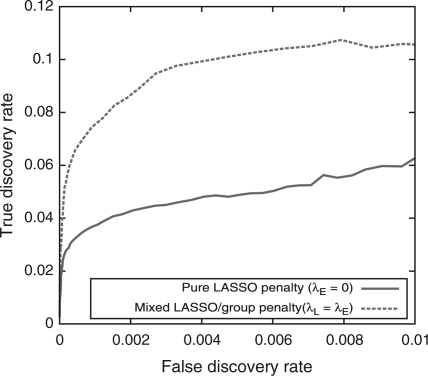

In the first example, we demonstrate how a mixed L1 and L2 penalization scheme can be beneficial for rare variant analyses by carrying out a simulation study based on real data from Pilot 3 of the 1000 Genomes Project. We assigned 100 genic SNPs, most of which had a minor allele frequency <0.01 to be causal with a relative risk of disease of 2.0. Figure 1, which presents power as a function of false discovery rate (FDR), shows that, as expected, inclusion of a mixed penalty (in this specific case, L1 = L2) can improve power over a pure L1 penalty when informative groupings (i.e. genes) are defined.

Fig. 1.

ROC for simulations based on 1KGP exome data.

In our second example, we apply the method of stability selection (Meinshausen and Bühlmann, 2010), which has been demonstrated to provide good error control in gene expression data, to a large GWAS on prostate cancer genotyped across 1 047 986 SNPs on 9641 African-American men (Haiman et al., 2011). We fit the model across 100 subsampled replicates of the data, completing analysis in slightly under 3.5 h. Based on our benchmarks (Table 1), we estimate this analysis would have completed in ~9 days on a single CPU using the same algorithm.

Table 2 presents the three variables declared as being stable based on a threshold (derived as a function of a pure L1 penalty) that controls FDR at the 0.05 level. The first two SNPs listed in the table replicate significant findings in earlier studies of prostate cancer (Murabito et al., 2007; Schumacher et al., 2011) while the last SNP appears to be a genuinely novel risk variant as we have recently replicated this finding in an independent Stage 2 analysis (Haiman et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Stable variables

| SNP ID | Chr | Position | Selection probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs10505483 | 8 | 128 194 377 | 0.68 |

| rs7130881 | 11 | 68 752 534 | 0.95 |

| rs7210100 | 17 | 44 791 748 | 0.8 |

All reported variables based on a threshold πthr=0.506 which controls FDR at <0.05

4 DISCUSSION

We describe our scalable framework gpu-lasso, which can be particularly useful for fitting sparse models in high-dimensional settings. To demonstrate how one can carry out Monte Carlo routines with our framework, we provide full source code listing for the C++ class that implements Stability Selection in our Supplementary Material. We should stress that our choice of GCD as our optimization routine may not be ideal in other contexts, particularly when large models need to be estimated, such as exploration of the entire LASSO path over a grid of values for the optimal penalty parameter. In this case, cyclic coordinate descent may be preferable as first, the increased number of iterations for GCD may swamp out gains from limited parallel resources, and second, GCD may potentially converge to models that overestimate sparsity. Alternatively, one could conceivably constrain the search to a set of candidate (sparse) models by adding a BIC penalty for example. For smaller datasets, software such as glmnet can be more practical, since efficient routines like the LARS algorithm (Efron et al., 2004), which solves the LASSO path without exploring a penalty parameter grid, are already bundled. As datasets increase in sample size, LARS and related approaches can lose their edge over a simple (parallelized) penalty grid search since such methods require inversion of a covariance matrix with dimension bounded by the number of samples [i.e. O(n)].

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to thank Kenneth Lange and Marc Suchard for their insights, Kai Wang and Paul Thomas for early feedback, the USC Epigenome Center for GPU computing resources and the African American Prostate Cancer Consortium, listed in (Haiman et al., 2011), for contributing data in the GWAS application.

Funding: This work was funded by National Institutes of Health grant (R01 ES019876-01A1).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Efron B., et al. Least angle regression. Ann. Statist. 2004;32:407–499. (With discussion, and a rejoinder by the authors) [Google Scholar]

- Friedman J.H., et al. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J. Stat. Softwr. 2010;33:1–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haiman C.A., et al. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer in men of African ancestry identifies a susceptibility locus at 17q21. Nat. Genet. 2011;43:570–573. doi: 10.1038/ng.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meinshausen N., Bühlmann P. Stability selection. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 2010;72:417–473. [Google Scholar]

- Murabito J.M., et al. A genome-wide association study of breast and prostate cancer in the NHLBI's Framingham Heart Study. BMC Med. Genet. 2007;8(Suppl. 1):S6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher F.R., et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new prostate cancer susceptibility loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:3867–3875. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H., et al. Association screening of common and rare genetic variants by penalized regression. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2375–2382. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.