Abstract

Live vaccines have long been known to trigger far more vigorous immune responses than their killed counterparts1–6. This has been attributed to the ability of live microorganisms to replicate and express specialized virulence factors that facilitate invasion and infection of their hosts7. However, protective immunization can often be achieved with a single injection of live, but not dead, attenuated microorganisms stripped of their virulence factors. Pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), which serve to alert the immune system8,9, are present in both live and killed vaccines, suggesting that certain poorly characterized aspects of live microorganisms, not incorporated in dead vaccines, are particularly effective at inducing protective immunity. Here we show that the innate immune system can directly sense microbial viability through detection of a special class of viability-associated PAMPs (vita-PAMPs). We identify prokaryotic messenger RNA (mRNA) as a vita-PAMP present only in viable bacteria, recognition of which elicits a unique innate response and a robust adaptive antibody response. Notably, the innate response evoked by viability and prokaryotic mRNA was thus far considered to be reserved for pathogenic bacteria, but we show that even nonpathogenic bacteria in sterile tissues can trigger similar responses, provided they are alive. Thus, the immune system actively gauges the infectious risk by scouring PAMPs for signatures of microbial life and thus infectivity. Detection of vita-PAMPs triggers an alert mode not warranted for dead bacteria. Vaccine formulations that incorporate vita-PAMPs could thus combine the superior protection of live vaccines with the safety of dead vaccines.

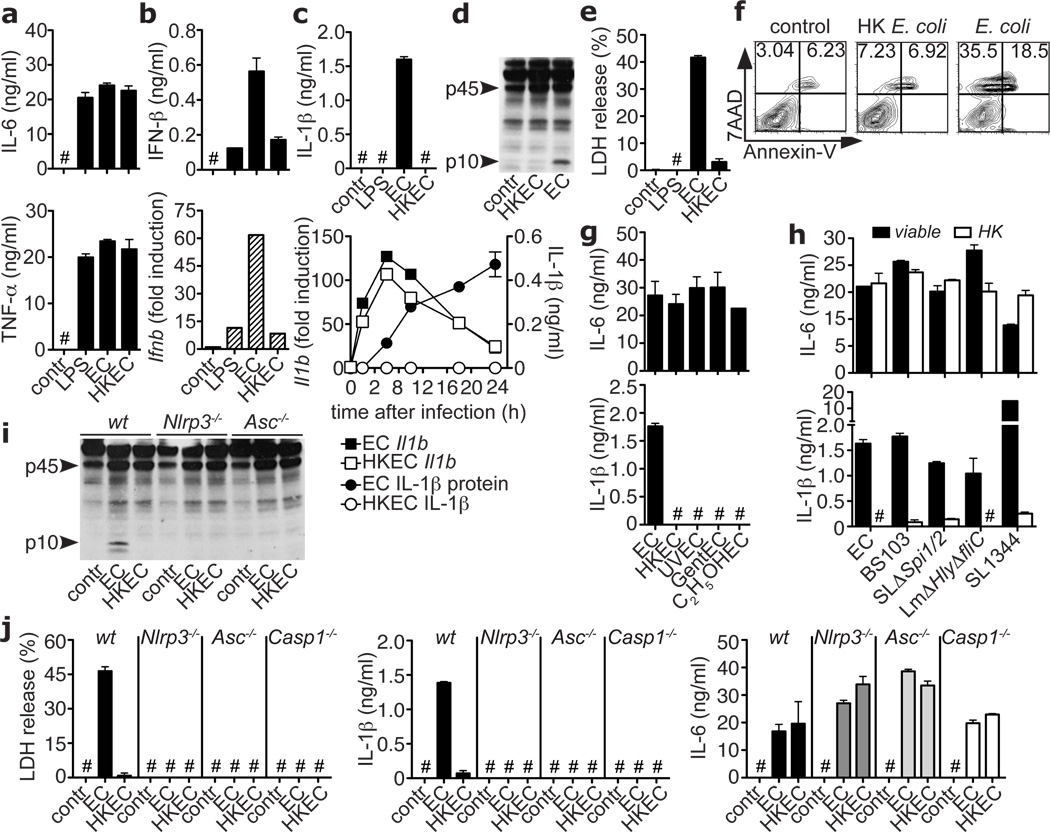

We hypothesized that the innate immune system may sense the most fundamental characteristic of microbial infectivity, microbial viability itself, and activate a robust immune response regardless of the presence of more specialized factors that regulate microbial virulence7. To study sensing of bacterial viability without compounding effects of replication or virulence factors, we used thymidine auxotrophs of nonpathogenic Escherichia coli K12, strain DH5α (ECThyA—). Viable and heat-killed (HK) ECThyA— similarly activated nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 (supplementary Fig. 1) in bone marrow-derived macrophages and elicited production of similar amounts of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (Fig. 1a). In stark contrast, viable ECThyA— induced higher levels of IFN-β than HK ECThyA— or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Fig. 1b), and only viable ECThyA— induced IL-1β secretion (Fig. 1c; supplementary Fig. 2). Pro-IL-1β transcription was equally induced by both viable and HK ECThyA— (Fig. 1c), suggesting that viable bacteria specifically elicit cleavage of pro-IL-1β. This process is catalyzed by caspase-1 in Nod-like receptor (NLR)-containing inflammasome complexes, assembly of which can be triggered by the activity of bacterial virulence factors10,11. Notably, avirulent viable but not HK ECThyA— induced inflammasome activation and pro-caspase-1 cleavage (Fig. 1d). Finally, viable but not HK ECThyA— induced caspase-1-dependent inflammatory cell death, termed pyroptosis10,11, resulting in release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (Fig. 1e) and appearance of 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD)+Annexin-V−/low cells (Fig. 1f). Similar responses were observed in peritoneal macrophages and both splenic and bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (supplementary Fig. 2b). Killing ECThyA— by UV irradiation, antibiotics, or ethanol, also selectively abrogated IL-1β secretion and pyroptosis without affecting IL-6 production (Fig. 1g; supplementary Fig. 3), suggesting that a general determinant associated with bacterial viability is detected.

Figure 1. Sensing bacterial viability induces IFN-β and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in the absence of virulence factors.

a. IL-6, TNF-α, b. IFN-β protein, mRNA (at 2h) in BMM stimulated with medium (contr), Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), ThyA— E. coli (EC), and heat-killed EC (HKEC), MOI=20. c. IL-1β (top), and Il1b mRNA (left y-axis), secreted IL-1β (right y-axis) at indicated times (bottom). d, i. Caspase-1 immunoblots at 18h. Pyroptosis by LDH release (e), and FACS (f) at 18h. IL-6 and IL-1β in response to EC, viable or killed by different means (g, BMDC), or viable or HK: EC, attenuated Shigella, Salmonella, and Listeria, or virulent Salmonella SL1344 (h). j. LDH, IL-1β, and IL-6. All responses by BMM and measured at 24h unless indicated otherwise. #, ‘Not detected’. Data represent ≥5 experiments. All bars represent mean ± s.e.m.

To determine whether pathogenic bacteria can also activate the inflammasome in the absence of virulence factors, we studied attenuated strains of selected pathogens: Shigella flexneri virulence plasmid-cured strain BS10312, Salmonella typhimurium, SL1344ΔSpi1ΔSpi2, lacking the Salmonella pathogenicity islands SPI-1 and SPI-210, and Listeria monocytogenes ΔHlyΔfliC, lacking listeriolysin O and flagellin10. These mutants induced IL-1β production at levels comparable to those induced by ECThyA— (Fig. 1h), but lower and with slower kinetics than their pathogenic counterparts (supplementary Fig. 4). IL-1β production was abolished when these bacteria were killed, whereas IL-6 production was similar (Fig. 1h). Thus, immune cells detect universal characteristics of viability different from virulence factors.

Caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis and IL-1β production in response to ECThyA— were abrogated in macrophages deficient for NLRP3 or for the inflammasome adaptor Apoptosis Speck protein with Caspase recruitment (ASC or PYCARD)11 (Figs. 1i,j), while NLRC4 was dispensable (supplementary Fig. 5). Pyroptosis and IL-1β production induced by viable ECThyA— were abrogated in Casp1−/− macrophages (Fig. 1j) and suppressed by inhibitors for caspase-1, but not caspase-8 (supplementary Fig. 6).

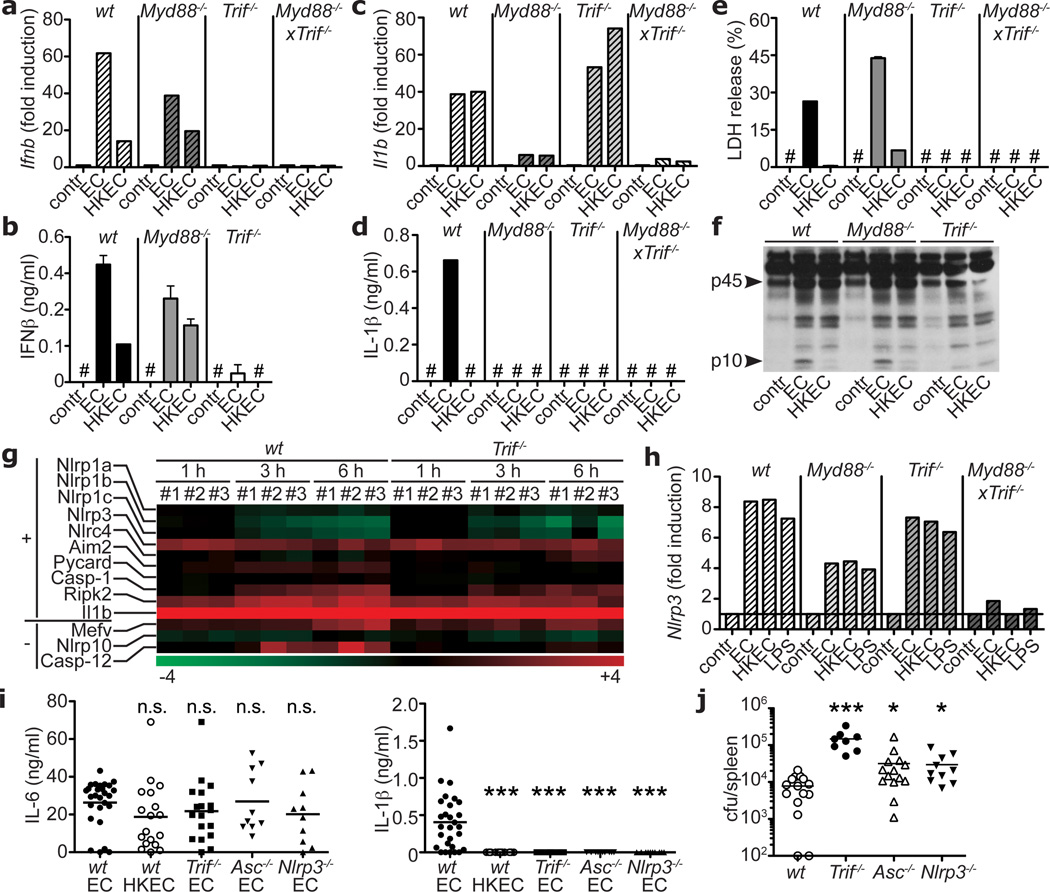

Induction of IFN-β mRNA and protein by viable ECThyA— required the Toll-like receptor (TLR) adaptor TRIF9 (Figs. 2a,b) and downstream interferon regulatory factor-3 (IRF3)9 (supplementary Fig. 7), but not MyD88, the main TLR adaptor9 (Figs. 2a,b). In contrast, transcription of pro-IL-1β was largely dependent on MyD88. Consequently, Myd88−/− cells secreted no IL-1β (Figs. 2c,d), whereas pyroptosis and caspase-1 cleavage were intact (Fig. 2e,f). Notably, while TRIF was dispensable for pro-IL-1β transcription (Fig. 2c), Trif−/− cells failed to secrete IL-1β (Fig. 2d), were protected from pyroptosis (Fig. 2e), and did not activate caspase-1 (Fig. 2f). These findings revealed an unexpected role for TRIF in NLRP3 inflammasome activation in response to viable ECThyA—. In contrast, pyroptosis induced by pathogenic S. typhimurium10, proceeded independently of TRIF (supplementary Fig. 8). Differential involvement of TRIF, together with differences in magnitude and kinetics of the response (Fig. 1h; supplementary Fig. 4), indicated that inflammasome activation in response to virulence factors occurs in a manner distinct from that to viability.

Figure 2. The TLR signalling adaptor TRIF controls ‘viability-induced’ responses.

Ifnb transcription at 2h (a), IFN-β secretion at 24h (b), Il1b transcription at 2h (c), IL-1β secretion (d), and LDH (e) 24h after phagocytosis of viable or HKEC. f. Caspase-1 immunoblot at 18h. a–f. Data by BMM and represent ≥5 experiments. g. Gene microarray analysis of wt and Trif—/— BMM treated with viable EC for 1, 3 or 6h (three biological replicates #1–3). Heat map of positive regulators/essential components (‘+’) and negative regulators (‘−‘) of inflammasomes. h. Nlrp3 transcription at 1h in BMM. Serum IL-6 and IL-1β 6h after injection of 1×109 viable or 5×109 HKEC (i), and splenic bacterial burdens 72h after injection of 1×108 non-auxotroph EC (j) into wt, Trif—/—, Asc—/— and Nlrp3—/— mice. Each symbol represents one mouse. *; p≤0.05, **; p≤0.01, ***; p≤0.001. n.s., Not statistically significant. #, ‘Not detected’. All bars represent mean ± s.e.m.

Genome-wide transcriptional analysis of wild type and Trif−/− macrophages before and after phagocytosis of viable ECThyA— showed differential regulation of several clusters of genes (supplementary Fig. 9) including IFN-regulated genes, as expected9 (Figs. 2a,b; supplementary Fig. 10a), while most of Rel/NF-κB target genes were comparable (supplementary Fig. 10b). Nlrp3 expression was induced independently of TRIF (Figs. 2g,h) and negative regulators of inflammasome activity such as those encoded by Mediterranean fever (Mefv), Nlrp10 and Casp12 genes were also unchanged or expressed at higher levels in wild type macrophages (Fig. 2g), possibly due to negative feedback. Thus, the role of TRIF in inflammasome activation upon phagocytosis of viable ECThyA— is not explained by transcriptional control of inflammasome components (so called priming11). Furthermore, ATP and reactive oxygen species (ROS)11,13, known activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome, were not involved, as deficiency for P2X7R, required for ATP-mediated NLRP3 activation, did not affect pyroptosis or IL-1β production (supplementary Figs. 11a,b), and ROS accumulated equally in response to viable and HK ECThyA— independently of TRIF (supplementary Fig. 11c).

Injection of viable and HK ECThyA— into mice induced similarly high serum levels of IL-6 (Fig. 2i). In contrast, circulating IL-1β was detected only in mice infected with viable bacteria (Fig. 2i), while IFN-β levels were undetectable in all groups (not shown). Confirming our results in vitro, production of IL-1β (but not IL-6) in vivo also required TRIF, ASC, and NLRP3 (Fig. 2i). Injection of non-pathogenic S. typhimurium induced serum IL-1β levels comparable to those elicited by ECThyA—, which similarly depended on TRIF (supplementary Fig. 12). Although pathogenic S. typhimurium elicited higher levels of serum IL-1β than non-pathogenic Salmonella, this response was also severely reduced in Trif−/− mice, suggesting a previously unappreciated role for TRIF in Salmonella infection (supplementary Fig. 12). Importantly, deficiency in TRIF, ASC and NLRP3 impaired bacterial clearance during systemic infection with replication sufficient non-pathogenic E. coli (Fig. 2j). This failure was more dramatic in Trif−/− than in Asc−/− or Nlrp3−/− mice, possibly due to the central upstream role of TRIF in inflammasome activation and IFN-β production.

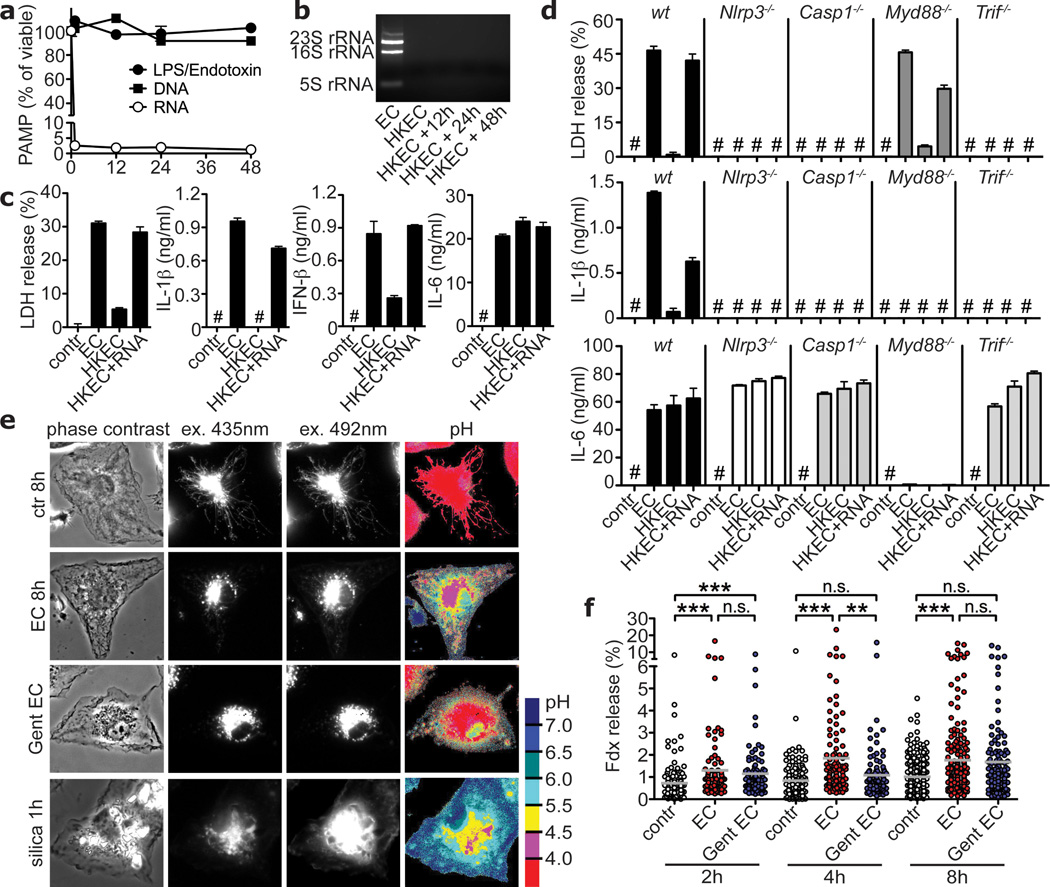

The ability to sense microbial viability through pathways downstream of pattern recognition receptors suggests the existence of vita-PAMPs; PAMPs associated with viable but not dead bacteria. In contrast to LPS and genomic DNA that remained constant after killing ECThyA— with heat, total bacterial RNA was rapidly lost (Figs. 3a,b; supplementary Fig. 13). Total RNA content was also lost with antibiotic treatment, and little ribosomal RNA (rRNA) remained after killing with UV and ethanol (supplementary Fig. 14). Only fixation with paraformaldehyde (PFA) efficiently killed the bacteria (not shown), but preserved total RNA content (supplementary Fig. 15a). Remarkably, unlike bacteria killed by other means, PFA-killed bacteria induced pyroptosis and IL-1β to levels similar to those induced by viable bacteria (supplementary Fig. 15b). Thus, the presence or absence of RNA correlated with the ability to activate pathways involved in sensing viability.

Figure 3. Bacterial RNA is a vita-PAMP that accesses cytosolic receptors during phagocytosis, and in the absence of virulence factors.

a. LPS/Endotoxin, genomic DNA and total RNA in EC before and at indicated times after heat killing. b. Agarose gel electrophoresis of EC total RNA before and after heat killing at 60°C for 60min followed by 4°C incubation for indicated times. c,d. LDH, IL-1β, IFN-β and IL-6 at 24h in response to viable and HKEC, or HKEC with 10µg/ml total EC RNA (HKEC+RNA). # in c,d, ‘Not detected’. a–d, Data by BMM represent ≥5 experiments. e. Representative ratiometric epifluorescence imaging of BMM at 8h with Fdx alone (ctr 8h), Fdx and viable EC (EC 8h) or gentamicin-killed EC (Gent EC) (colour code indicates pH scale). Positive control: Ground silica (silica 1h). f. Quantification of cytosolic Fdx (% of total Fdx/cell). Each dot represents % released Fdx/individual cell. Grey bars represent mean Fdx release. *; p≤0.05, **; p≤0.01, ***; p≤0.001. All bars represent mean ± s.e.m.

These results suggest that prokaryotic RNA represents a labile PAMP closely associated with bacterial viability, which might signify microbial life to the immune system. Indeed, addition of purified total bacterial RNA fully restored the ability of HK ECThyA— to induce pyroptosis, IL-1β and IFN-β production (Fig. 3c). These responses were dependent on TRIF, NLRP3 and caspase-1, just as those elicited by viable bacteria (Fig. 3d compared to Figs. 1j and 2a–f). The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates recognition of viral RNA during Influenza A infection14. Together with our results and others’15, this suggests a more general role for NLRP3 in responses to RNAs of microbial origin. RNA can activate the NLRP3 inflammasome when delivered into the cytosol (where NLRP3 resides) with transfection reagents15. In contrast, inflammasome activation by the combination of total bacterial RNA and dead ECThyA— did not require RNA transfection (Figs. 3c,d). Administration of total E. coli RNA alone or in combination with LPS (to mimic an E. coli-derived PAMP+RNA) had little effect on NLRP3 inflammasome activation unless the RNA was delivered to the cytosol using Lipofectamine (supplementary Fig. 16) or in combination with ATP, as reported previously15. Thus, phagocytosis of viable bacteria is a natural context of bacterial RNA-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome activation.

These findings raised the question as to how vita-PAMPs in phagolysosomes gain access to cytosolic receptors such as NLRP3 in the absence of invasion, auxiliary secretion systems or pore forming toxins. To address this question, we exploited the pH sensitive excitation spectrum of fluorescein: the acidic pH in phagolysosomes quenches fluorescence while release into the pH neutral cytosol allows a regain in fluorescence16. Phagocytosis of avirulent ECThyA— in the presence of fluorescein-conjugated dextran (Fdx), consistently induced low level release of Fdx into the cytosol of macrophages (Figs. 3e,f; supplementary Fig. 17). This indicates that phagosomes carrying E. coli exhibit intrinsic leakiness, a property previously described for particles such as beads and crystals that induce phagolysosomal destabilization16,17. Interestingly, killed E. coli also induced Fdx release, although to a slightly lower extent than viable E. coli (Figs. 3e,f) demonstrating that phagosomal leakage occurs independently of bacterial viability. Therefore, RNA from viable bacteria could gain access to cytosolic receptors via intrinsic phagosomal leakage. These results may also explain the reported ability of phagosome-degraded mutants of Listeria monocytogenes or Staphylococcus aureus to induce a transcriptional response dependent on cytosolic NLRs18,19.

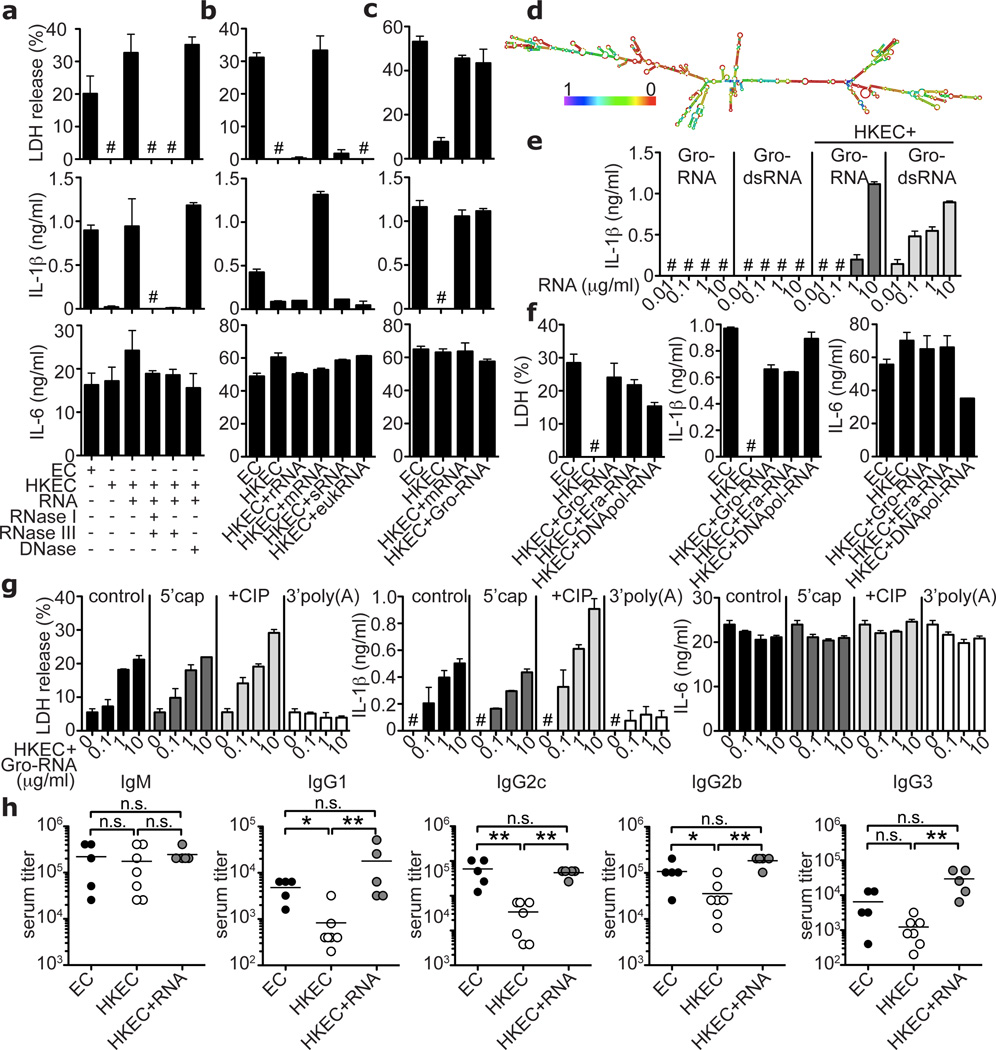

Digestion of total RNA from E. coli with exonuclease RNase I and double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)-specific endonuclease RNase III abrogated LDH and IL-1β release, while DNase treatment had no effect (Fig. 4a). Of E. coli RNA species, mRNA most potently induced pyroptosis as well as production of IL-1β and IFN-β. Small RNA (sRNA) or the most abundant RNA, ribosomal RNA (rRNA), had little or no detectable effects (Fig. 4b; supplementary Fig. 18). E. coli rRNA undergoes extensive modifications not found in mRNA20, which may underlie the differential activity of these RNA species. The relative amount of mRNA was <1% of the total RNA and accordingly, mRNA was approximately 100-fold more effective than total RNA (Figs. 3c, 4a,b; supplementary Fig. 18).

Figure 4. Bacterial messenger RNA constitutes an active vita-PAMP.

a–c and e–g. LDH, IL-1β and IL-6 at 24h. a. Total EC RNA treated with RNAse I and RNAse III, RNAse III alone, or DNAse prior to stimulation of BMDC. b. BMM treated with viable or HKEC, or HKEC with 0.1µg/ml of different bacterial RNA; ribosomal (rRNA), messenger (mRNA), small (sRNA) or eukaryotic RNA (eukRNA). c. BMDC responses. Gro-RNA; in vitro transcribed EC Gro-operon RNA. d. Predicted secondary structure of Gro-RNA. Colour code indicates base pairing probability. e. BMM treated with in vitro transcribed Gro-RNA or Gro dsRNA alone or with HKEC. f. BMDC responses. Era-RNA and DNApol-RNA; in vitro transcribed EC Era-GTPase and DNA-polymerase-III RNA, respectively. g. BMM treated with different doses of unmodified (control), or modified Gro-RNA with HKEC (5’cap, 5’ m7G capping; CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase; 3’poly(A), 3’-polyadenylation). a–g. #, ‘not detected’, all RNA at 10µg/ml except as noted, data represent ≥5 experiments. h. Mice vaccinated and boosted twice with viable EC, HKEC or HKEC with 30µg total purified bacterial RNA (HKEC+RNA) (vaccination regimen in suppl. Fig. 22). Class-specific anti-E. coli antibody serum titers at 25 days. *; p≤0.05, **; p≤0.01, ***; p≤0.001. All bars represent mean ± s.e.m.

In vitro transcribed single-stranded mRNA of the E. coli Gro-operon (supplementary Figs. 19a,b), which is strongly expressed upon phagocytosis of bacteria21, induced caspase-1 cleavage and subsequent pyroptosis and IL-1β production when phagocytosed together with HK ECThyA— (Fig. 4c,e; supplementary Figs. 19c–e). The single-stranded Gro-mRNA sequence had a predicted secondary structure with regions of high probability for base pairing (Fig. 4d), consistent with susceptibility of the stimulatory activity to RNase III treatment (Fig. 4a). Indeed, fully dsGro-mRNA (supplementary Fig. 19b) induced similar responses as single-stranded Gro-mRNA of the appropriate length (Fig. 4e; supplementary Fig. 19d). Other transcripts also induced such responses, showing that the immunostimulatory property is independent of RNA sequence (Fig. 4f).

Strikingly, eukaryotic RNA was unable to elicit the responses induced by E. coli mRNA (Fig. 4b). Unlike eukaryotic mRNA, tri-phosphate moieties at the 5’end of bacterial mRNAs are not capped with 7-methyl-guanosine (7m7G)22, and might betray the prokaryotic origin of these transcripts23. However, neither treatment with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) nor capping affected the activity of Gro-mRNA during phagocytosis of HK ECThyA— (Fig. 4g). The stimulatory activity of purified E. coli total RNA or mRNA was also unaltered by CIP treatment (supplementary Figs. 20a,b) arguing against a role for the RNA helicase retinoic acid inducible gene-I (RIG-I), which can induce interferon and IL-1β production, but requires 5’-tri-phosphates for activation (supplementary Fig. 20c)23. Moreover, TRIF and NLRP3 are dispensable for RIG-I function, but required for the stimulatory activity of bacterial RNA (Figs. 2a,b, 3d). Interestingly, RNA can induce RIG-I-dependent IFN-β during infection with an invasive intracellular bacterium24, suggesting that the nature of microbial pathogenesis and cellular context in which bacterial RNA is recognized, may determine the choice of innate sensors engaged. In contrast to 5’-triphosphate removal, adding polyadenylyl groups to the 3’end of Gro-mRNA or purified E. coli mRNA abrogated IL-1β secretion and pyroptosis (Fig. 4g; supplementary Fig. 21). Thus, absence of 3’-polyadenylation22 may allow specific detection of prokaryotic mRNA during infection. Additional features may distinguish self from microbial RNAs such as internal naturally occurring nucleoside modifications in eukaryotic RNA25–27.

To test the impact of vita-PAMPs on adaptive immunity, we immunized mice with either viable or dead ECThyA—, or a combination of dead ECThyA— and purified total bacterial RNA (supplementary Fig. 22). While all three vaccines induced similar polyclonal anti-E. coli IgM responses, production of class-switched IgG subclasses was strongly enhanced in response to vaccination with viable compared to killed E. coli (Fig. 4h). Adding total bacterial RNA to killed ECThyA— elevated IgG1, IgG2c, IgG2b and IgG3 antibody titers to or above the levels in mice immunized with viable ECThyA—. Thus, innate detection of bacterial viability leads to robust activation of a humoral adaptive response. These findings indicate that bacterial RNA can augment killed vaccines to perform as well as live ones.

Our findings reveal an inherent ability of the immune system to distinguish viable from dead microorganisms. The presence of live bacteria in sterile tissues, regardless of whether these (still) express virulence factors, poses an acute threat that must be dealt with by an aggressive immune response. Dead bacteria, on the other hand, would signify a successful immune response that can now subside. Detection of vita-PAMPs within sterile tissues signifies microbial viability. Other vita-PAMPs may exist in the form of second messengers like cyclic di-adenosine or di-guanosine monophosphates7,28 or quorum-sensing molecules7. The extent to which vita-PAMPs contribute to the host response during natural infection with pathogenic bacteria, relative to other stimuli such as the activity of virulence factors, is an important issue that requires further investigation. Given that bacteria tightly regulate their virulence via multiple mechanisms in response to different environmental signals and inside a host organism during infection29,30, detection of invariant vita-PAMPs essential to bacterial survival may be a non-redundant fail-safe strategy for host protection.

Methods summary

Cells were infected with E. coli DH5α ThyA— at MOI of 20 for 24 h unless stated otherwise. Supernatants were assayed for cytokines by ELISA. Genome wide transcriptional analysis of BMM at 0, 1, 3 and 6 h post infection was carried out on Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.1 ST 24-array plates. Phagosomal leakage in BMM was detected by measuring Fdx release using a modified method previously described16. In brief, BMM were treated with ECThyA— in presence of 0.167 mg/ml Fdx and imaged with excitation at 440nm (pH insensitive) and 485nm (pH sensitive). Fluorescence intensity ratios at 485nm/440nm were converted into pH maps and % Fdx release calculated (total intensity of pixels containing released Fdx/total Fdx intensity). Bacterial RNA was extracted from E. coli using the e.z.n.a RNA kit (Omega) and in vitro transcription of bacterial genes carried out using the MEGAscript kit (Ambion) followed by DNase digestion and RNA purification using MEGAclear kit (Ambion). RNA polyadenylation was performed with the poly-A-tailing kit (Ambion). Vaccinations were performed as a prime-boost regimen (see full Methods). C57BL/6J and P2rx7−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. MyD88−/−, Trif−/− mice were provided by S. Akira, Myd88−/x−Trif−/− by R. Medzhitov, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/−, Nlrc4−/− by Millenium, and Caspase-1−/− by R. Flavell. Animal care and experimentation were performed in accordance with approved MSSM Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols.

Methods

Cells

Bone marrow (BM)-derived dendritic cell (DC) cultures were grown as previously described31 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with GM-CSF and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS), plus 100 µg/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 1 nM sodium pyruvate, 1% MEM non-essential amino acids, and 2.5 µM β-mercaptoethanol (all SIGMA). Semi-adherent cells were harvested on ice on day 5 and re-plated immediately in fresh RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS at 1×106 cells/well in 24-well tissue culture-treated plates. Stimuli were added immediately after re-plating in the same medium and the cells were centrifuged for 2’ at 2000 rpm. Murine macrophages were derived from the BM (BMM) of either C57BL/6J, Myd88−/−, Trif−/−, Trif−/−xMyd88−/−, Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− or Casp1−/− mice, as described previously32, in RPMI 1640 supplemented with M-CSF and 10% FBS, plus 100µg/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin, 10mM HEPES and 1nM sodium pyruvate (all SIGMA). For some experiments macrophages were derived from BM of Irf3−/− or P2rx7−/− mice. Peritoneal macrophages were harvested 72h after intra-peritoneal injection of 1ml thioglycollate (BD Bioscience), grown overnight in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and 100µg/ml penicillin and 100µg/ml streptomycin, hereafter referred to as ‘complete medium’. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deficient for RIG-I (RIG-I−/−) were kindly provided by A. Ting with permission from S. Akira, and grown in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS and 100 µg/ml penicillin, 100µg/ml streptomycin.

Mice

C57BL/6J and P2rx7−/− mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. Myd88−/− and Trif−/− mice were originally provided by S. Akira, Myd88−/− and Trif−/− mice were interbred to homozygosity to generate TrifxMyd88−/− mice, and were provided by R. Medzhitov. Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/− or Casp1−/− bone marrow was provided by B. Ryffel and mice for in vivo studies were acquired from R. Flavell (through Millenium) and have been described previously33,34. Irf3−/− mice were provided by C.B. Lopez and were previously described35. We used 8–10 week old animals for all experiments. All experiments were approved by the institutional ethics committee and carried out in agreement with the ‘Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ (NIH publication 86-23, revised 1985).

Bacteria

E. coli K12, strain DH5α were purchased from Invitrogen. Naturally occurring Thymidine auxotrophs (ThyA—) were selected on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates containing 50µg/ml trimethoprim and 500µg/ml thymidine (both SIGMA). Auxotrophy was confirmed by inoculation and overnight culture of single colonies in LB medium. ThyA— E. coli grew only in the presence of thymidine and were resistant to trimethoprim. For phagocytosis experiments, ThyA— E. coli were grown to mid log phase, washed 3 times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove thymidine and LB salts prior to addition to cells. For heat killing, ThyA— E. coli were grown to log phase, washed and resuspended in PBS at an OD600 of 0.6, and subsequently incubated at 60°C for 60 minutes. ThyA— heat killed (HK) E. coli were stored up to 18 hours at 4°C or used immediately after cooling. Efficient killing was confirmed by overnight plating on thymidine/trimethoprim supplemented LB-agar plates. For gentamicin killing, ThyA— E. coli were grown to mid log phase, washed and resuspended in LB medium containing thymidine, trimethoprim and 50µg/ml gentamicin sulfate and incubated in a shaking incubator at 37°C overnight. Ethanol killing was carried out by resuspending log phase ThyA— E. coli in 70% Ethanol for 10 minutes, followed by extensive washing in PBS. For UV killing, log phase ThyA— E. coli were resuspended in PBS at an OD600 of 0.6, UV-irradiated with 1000mJ/cm2 in a Petri dish followed by washing with PBS. Paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation was performed by resuspending log phase ThyA— E. coli in 4% PFA in PBS for 10 minutes followed by extensive washing and resuspension in PBS. Shigella flexneri virulence plasmid-cured strain BS103 was kindly provided by M.B. Goldberg12,36. ThyA— S. flexneri were selected similarly to E. coli ThyA—. D.M. Monack kindly provided Salmonella typhimurium, strain SL1344 ΔSpi1ΔSpi2, lacking the Salmonella pathogenicity island SPI-1 and SPI-2 Type-III secretion systems37. SL1344 ΔSpi1ΔSpi2 was grown in LB medium containing 25µg/ml kanamycin and 12µg/ml tetracycline. Listeria monocytogenes ΔHlyΔfliC lacking listeriolysin O (LLO) and flagellin expression were kindly provided by D. Portnoy38.

Treatment of macrophages and dendritic cells with viable and killed bacteria

Macrophages were detached and re-plated 4 hours prior to the experiment. BMDC were re-plated immediately before addition of bacteria or soluble ligands. Unless stated otherwise, bacteria were used at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 20. All experiments were carried out in antibiotic-free ‘complete medium’. One hour after addition of bacteria, penicillin (100µg/ml) and streptomycin (100µg/ml) were added to the medium in order to kill any remaining extracellular bacteria. Alternatively, gentamicin sulfate (50µg/ml) was used. We also compared this approach to washing the cells and replacing the antibiotic-free medium with penicillin/streptomycin containing medium after one hour and found no differences with regards to the cellular responses measured. Supernatants were collected 24 hours after addition of the bacteria unless stated otherwise in the figure legends.

Cytokine Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assays (ELISA)

Supernatants from cultured BMM or BMDC were collected at 24 hours after stimulation or at the times indicated. ELISA antibody (Ab) pairs used for IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α were as listed below. All ELISA Abs were used at 2µg/ml capture and 0.5 µg/ml detection, with the exception of IL-6 capture, which was used at 1µg/ml. Detection antibodies were biotinylated and labeled by streptavidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and visualized by addition of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (SIGMA) (from tablets) or 3,3', 5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine solution (TMB, KPL). Color development was stopped with 3M H2SO4 or TMB-Stop Solution (KPL), respectively. Recombinant cytokines served as standards and were purchased from Peprotech. Absorbances at 492 or 450nm were measured, respectively, on a tunable microplate reader (VersaMax, Molecular Devices). Cytokine supernatant concentrations were calculated by extrapolating absorbance values from standard curves where known concentrations were plotted against absorbance using SoftMax Pro 5 software. Capture/detection Ab pairs were as follows. IL-6: MP5-20F3/MP5-32C11 (BDPharmingen), IL-1β: B12/rabbit polyclonal Ab (eBioscience), TNF-α: TN3-19/rabbit polyclonal Ab (eBioscience). IFN-β production was measured from supernatants using the VeriKine™ Mouse IFN-Beta ELISA Kit (PBL Interferon source) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Anti-E. coli antibody ELISA

96-well microtiter plates were coated overnight with E. coli lysates (3µg/ml) that we generated from log-phase cultures of ThyA— E. coli. Serum samples from immunized mice were serially diluted (12 dilutions) and incubated in the pre-coated plates for 12 hours at 4°C followed by washing and incubation with rabbit anti-mouse isotype specific Ig-HRP (Southern Biotech) for 1 hour. Bound rabbit anti-mouse Ig-HRP was visualized by addition of o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (SIGMA) from tablets, and the anti-E. coli antibody titers for each mouse were determined by absorbance readings at 490nm.

Measurement of inflammatory cell death

Cell death of macrophages or BMDC was measured using the Cytotox96 cytotoxicity assay (Promega) following manufacturer’s instructions. The assay measures release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) into the supernatant calculated as percent of total LDH content, measured from cellular lysates (100%). LDH released by unstimulated cells was used for background correction.

Flow cytometric assessment of cell death

Cells were stimulated overnight, stained for Annexin V / 7AAD using the Annexin V-PE / 7AAD Apoptosis Detection kit (BD Pharmingen), and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD).

Flow cytometric measurement of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-production

BMM were loaded with the ROS indicator dye H2DCFDA (Molecular Probes/Invitrogen, 10mM in PBS) for 30 minutes followed by a recovery time of 30 min in fresh pre-warmed ‘complete medium’. BMM were then stimulated with viable or HK E. coli for 60 minutes, washed and analyzed by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur, BD).

Western Blots

For detection of Caspase-1, protein extracts were separated on 4–12% SDS-gradient gels (Invitrogen). For detection of all other proteins, samples were run on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in PBS and probed with the following Abs: Caspase-1 p10 (M-20) / rabbit polyclonal Ab, IκB-α (C-21) / rabbit polyclonal Ab (both from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies), Phospho-IRF3 (Ser396) / rabbit polyclonal Ab, IRF3 / rabbit polyclonal Ab, Phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) / rabbit polyclonal Ab, p38 MAPK / rabbit polyclonal Ab (all from Cell Signalling Technology), α-tubulin (DM1A) / rabbit monoclonal Ab (Novus Biologicals).

Real time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from macrophages using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Contaminating genomic DNA was removed by DNase digestion (DNase I, Promega). Reverse transcription was performed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) and cDNA was used for subsequent real time PCR reactions. Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was conducted on an ABI Prism 7900 instrument using the Maxima™ SYBR green qPCR Master Mix (Fermentas) with the following primer pairs. β-Actin: FW 5’-GAAGTCCCTCACCCTCCCAA-3’, RV 5’-GGCATGGACGCGACCA-3’; Il1b: FW 5’ AAAGACGGCACACCCACCCTGC-3’, RV 5’ TGTCCTGACCACTGTTGTTTCCCAG-3’; Ifnb: FW 5’ GCACTGGGTGGAAT 3’, RV 5’ TTCTGAGGCATCAA 3’; Nlrp3: FW 5’ CGAGACCTCTGGGAAAAAGCT 3’, RV 5’ GCATACCATAGAGGAATGTGATGTACA 3’. All reactions were performed in duplicates and the samples were normalized to β-actin. “Fold inductions” were calculated using the ΔΔCt method relative to unstimulated BMM.

Transcriptome analysis

BMM derived from wild type (wt) or Trif−/− mice were stimulated with viable E. coli for 0, 1, 3 or 6 hours and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN). RNA from three independent experiments was used for transcriptional analysis. RNA integrity was checked on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) with 6000 Nano Chips. RNA was judged as suitable only if samples showed intact bands of 18S and 28S ribosomal RNA subunits, displayed no chromosomal peaks or RNA degradation products, and had a RNA integrity number (RIN) above 8.0.

One hundred nanograms of RNA were used for whole transcript cDNA synthesis with the Ambion WT expression kit (Applied Biosystems, Nieuwekerk a/d IJssel, The Netherlands). Hybridization, washing and scanning of an Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.1 ST 24-array plate was carried out according to standard Affymetrix protocols on a GeneTitan instrument (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA).

Packages from the Bioconductor project, integrated in an in-house developed management and analysis database for microarray experiments, were used for analysis of the scanned arrays39. Arrays were normalized using the Robust Multi-array Average method40,41. Probe sets were defined according to Dai et al.42. With this method probes are assigned to unique gene identifiers, in this case Entrez IDs. The probes on the Gene 1.1 ST arrays represent 19,807 genes that have at least 10 probes per identifier. For the analysis, only genes that had an intensity value of > 20 on at least two arrays were taken into account. In addition, the interquartile range of log2 intensities had to be at least 0.25. These criteria were met by 9,921 genes. Changes in gene expression are represented as signal log ratios between treatment and control. Multiple Experiment Viewer software (MeV 4.6.1) was used to create heatmaps43,44. Genes were clustered by average linkage hierarchical clustering using Pearson correlation. Significantly regulated genes were identified by Intensity-based moderated t-statistics45. Obtained p-values were corrected for multiple testing by a false discovery rate method46.

IFN-regulated genes were identified using the Interferome database (www.interferome.org)47 and grouped in a heat map. Rel/NF-κB target genes were identified using another online database (http://bioinfo.lifl.fr/NF-KB/) which compiles Rel/NF-κB target genes identified by various groups48,(http://people.bu.edu/gilmore/nfkb/index.html). Inflammasome-related genes were compiled based on the current literature11,49.

Measuring release from bacterial phagosomes

Measurement of fluorescein-dextran (Fdx) release from macrophage phagosomes was performed using a modified method previously described16. BMM were plated onto Mat-tek coverslip dishes (MatTek Corp. Ashland, MA, USA) and incubated overnight. BMM were stimulated with viable or gentamicin-killed red fluorescent protein (RFP)-expressing ThyA— E. coli in the presence of 0.167 mg/mL Fdx in 200 µL of medium. After 120 minutes of co-culture, additional Fdx and gentamicin containing medium was added to the coverslip dishes to prevent drying and to prevent bacterial overgrowth. Cells were imaged after 2, 4 and 8 hours to measure release of Fdx. Microscopic imaging was performed on an IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA, USA) equipped with an X-cite 120 metal halide light source (EXFO, Mississauga, ON, Canada) and excitation and emission filter wheels. Phase contrast and two fluorescent images were acquired for each field of cells. The fluorescent images used the same emission settings, but used different excitation band-pass filters. Fdx fluorescence intensity using an excitation filter centred at 440 nm is relatively insensitive to pH, while fluorescence intensity using an excitation filter centered at 485 is very sensitive to pH. The ratio of fluorescence intensity at 485 nm divided by 440 nm was converted to into pH maps using calibration curves generated by imaging BMM with Fdx containing compartments at a series of fixed pH conditions. As described previously16, pixels with pH above 5.5 were designated as representing Fdx which has been released from endo-lysosomal compartments. Percent of Fdx release was calculated by dividing the total intensity of pixels containing released Fdx by the total Fdx intensity for each cell.

Infections and vaccinations

For measurements of systemic cytokine levels, C57BL/6J wt, Trif−/−, Asc−/− or Nlrp3−/− mice were injected with 1×109 viable or 5×109 HK ThyA— E. coli, respectively. Blood samples were drawn 6 hours post infection, and cytokine concentrations were measured by ELISA. For determination of bacterial clearance, we infected mice with 5×107 viable replication-sufficient E. coli by intraperitoneal injection. Mice were monitored daily and moribund animals were sacrificed according to humane criteria established and approved by our institutional IACUC committee. After 60 hours, animals were euthanized and the spleens were explanted, homogenized, serially diluted and plated on LB-agar plates overnight followed by colony forming units (cfu) counting.

For vaccinations, we followed a prime-boost regimen as shown in the schematic in Figure 4h that was adopted from a previous study50. In brief, mice received an initial vaccination intraperitoneally with 5×107 cfu of viable or HK ThyA— E. coli or a combination of 5×107 cfu HK ThyA— E. coli and 30µg of purified E. coli total RNA, followed by two boosts (5×106 cfu) after 10 and 20 days. Polyclonal class-specific anti-E. coli antibody production was measured in the serum after 25 days by ELISA.

Bacterial RNA

Total bacterial RNA was isolated from ThyA— E. coli using the e.z.n.a. Bacterial RNA Kit (Omega Bio-Tek), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Contaminating DNA was removed by DNase digestion (TURBO DNase, Ambion/Applied Biosystems). Alternatively, total purified E. coli (DH5α) RNA was purchased from Ambion/Applied Biosystems, and similar results were obtained. Fractionation of bacterial RNA species was performed as follows. First, ribosomal 16S and 23S RNA (rRNA) was removed by a magnetic bead based capture hybridization approach using the MICROBExpress™ kit (Ambion/Applied Biosystems). The enriched RNA was then separated into messenger RNA (mRNA) and small RNA (sRNA, including 5S rRNA) using the MEGAClear™ kit (Ambion/Applied Biosystems). All separated RNA fractions were precipitated with ammonium acetate and resuspended in nuclease free water. RNA concentration and purity were determined by measuring the absorbance at 260/280 and 260/230 nm. RNA preparations were further visualized by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

In vitro RNA transcription

The E. coli Gro-operon encoding the bacterial chaperonins GroEL and GroES, the GTPase Era-operon or the DNA-polymerase-III-operon were PCR amplified from genomic DNA isolated from ThyA— E. coli using primer pairs containing a T7 promotor sequence (T7) in either the FW or both FW and RV primer. Gro-FWT7 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCACCAGCCGGGAAACCACG-3’; Gro-RVT7 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGAAAAGAAAAACCCCCAGACAT-3’; Gro-RV 5’-AGATGACCAAAAGAAAAACCCCCAGACATT-3’; Era-FWT7 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCATATGAGCATCGATAAAAGTTAC-3’; Era-RV 5’-TTTAAAGATCGTCAACGTAACCGAG-3’; DNApol-FWT7 5’-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGGATGTCTGAACCACGTTTCGT-3’; DNApol-RV 5’-AGTCAAACTCCAGTTCCACCTGCTCCGAA-3’.

PCR fragments were purified using Nucleospin Extract II PCR purification kit (Macherey-Nagel), and used as DNA templates for in vitro transcription. In vitro transcription was performed using MEGAscript kit T7 (Ambion/Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA templates generated with Gro-FWT7 and Gro-RV primers only contained a T7 promotor site in the sense strand and yielded single-stranded RNA, whereas PCR templates generated with Gro-FWT7 and Gro-RVT7 primers contained T7 promotor sequences in both strands, allowing transcription of two complementary strands, yielding double-stranded RNA. For generation of 5’-capped RNA, m7G(5’)ppp(5’)G cap analog (Ambion/Applied Biosystems) was included in the transcription reaction at a GTP:cap ratio of 1:4.

RNA digestion, dephosphorylation and polyadenylation

In vitro transcribed Gro RNA, total E. coli RNA or E. coli mRNA were digested using RNase I (Promega) and RNase III (Ambion/Applied Biosystems). To remove 5’-triphosphates, RNA dephosphorylation was performed by incubating 10µg in vitro transcribed RNA or total E. coli RNA or 1mg of E. coli mRNA with 30U of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP, New England Biolabs) for 2 hours at 37°C, as described previously51. Polyadenylation of in vitro transcribed and purified bacterial mRNA was performed using the poly(A) Tailing kit (Ambion) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transfection of macrophages and MEFs

For direct cytosolic delivery of total purified E. coli RNA or in vitro transcribed Gro RNA, 5×105 BMM or 2×105 MEFs were transfected with 1mg of RNA using 2µl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in 24- or 12-well plates, respectively.

Soluble ligands, inhibitors and other reagents

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was purchased from SIGMA (E. coli 055:B5, phenol extracted). Caspase inhibitors z-YVAD, z-IEDT, Q-VD-OPH (all SM Biochemicals) were used at 50µM, and added 30’ prior to stimulation of cells.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significances were tested by ANOVA Kruskall-Wallis test and Bonferroni-Dunn post hoc correction. Significances are represented in the figures as follows; *; p≤0.05, **; p≤0.01, ***; p≤0.001. n.s., not statistically significant, #, ‘Not detected’.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to R. Medzhitov and J. C. Kagan for critical reading of the manuscript, C.B. Lopez for Irf3−/− mice, D.M. Monack for Salmonella ΔSpi1ΔSpi2, M.B. Goldberg for Shigella BS103, and D.A. Portnoy for Listeria ΔHlyΔFliC. We thank M. Rivieccio, I. Brodsky, M. Blander, S.J. Blander, J. Sander and Blander lab members for insightful discussions, help and support. L.E.S. was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft grant SA-1940/1-1, D.A. by fellowships from the Academic Medical Center and the Landsteiner Foundation for Blood Research, M.V.B. and M.M. by the Netherlands Nutrigenomics Centre. This work was supported by NIH grant AI080959A, and the Kinship Foundation Searle Scholar award to J.M.B.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions. L.E.S. and J.M.B. designed experiments and directed the study. L.E.S. performed all experiments. M.J.D. and L.E.S. performed experiments measuring lysosomal leakage. J.A.S. helped with the design and analysis of the lysosomal leakage experiments. M.V.B. performed gene microarray analysis. M.V.B. and M.M. analyzed the gene microarray data and helped with data interpretation. D.A. and J.M.B. performed experiments during development phase of the project, and C.C.D. helped with design of RNA related experiments. B.R. provided bone marrow progenitor cells from Nlrp3−/−, Asc−/−, and Casp1−/− mice. L.E.S., D.A. and J.M.B. wrote the manuscript. J.M.B. conceived of the study.

Author information. Affymetrix Microarray data have been deposited with the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession no. GSE27960.

References

- 1.Brockstedt DG, et al. Killed but metabolically active microbes: a new vaccine paradigm for eliciting effector T-cell responses and protective immunity. Nat Med. 2005;11:853–860. doi: 10.1038/nm1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheers C, Zhan Y. How do macrophages distinguish the living from the dead? Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:453–455. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(96)10067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Detmer A, Glenting J. Live bacterial vaccines--a review and identification of potential hazards. Microb Cell Fact. 2006;5:23. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawamura I, et al. Antigen provoking gamma interferon production in response to Mycobacterium bovis BCG and functional difference in T-cell responses to this antigen between viable and killed BCG-immunized mice. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4396–4403. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4396-4403.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauvau G, et al. Priming of memory but not effector CD8 T cells by a killed bacterial vaccine. Science. 2001;294:1735–1739. doi: 10.1126/science.1064571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Koenig CH, Finger H, Hof H. Failure of killed Listeria monocytogenes vaccine to produce protective immunity. Nature. 1982;297:233–234. doi: 10.1038/297233a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vance RE, Isberg RR, Portnoy DA. Patterns of pathogenesis: discrimination of pathogenic and nonpathogenic microbes by the innate immune system. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:10–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medzhitov R. Approaching the asymptote: 20 years later. Immunity. 2009;30:766–775. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mariathasan S, Monack DM. Inflammasome adaptors and sensors: intracellular regulators of infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:31–40. doi: 10.1038/nri1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroder K, Tschopp J. The inflammasomes. Cell. 2010;140:821–832. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wing HJ, Yan AW, Goldman SR, Goldberg MB. Regulation of IcsP, the outer membrane protease of the Shigella actin tail assembly protein IcsA, by virulence plasmid regulators VirF and VirB. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:699–705. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.3.699-705.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–225. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pang IK, Iwasaki A. Inflammasomes as mediators of immunity against influenza virus. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanneganti TD, et al. Bacterial RNA and small antiviral compounds activate caspase-1 through cryopyrin/Nalp3. Nature. 2006;440:233–236. doi: 10.1038/nature04517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis MJ, Swanson JA. Technical advance: Caspase-1 activation and IL-1beta release correlate with the degree of lysosome damage, as illustrated by a novel imaging method to quantify phagolysosome damage. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:813–822. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornung V, et al. Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:847–856. doi: 10.1038/ni.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herskovits AA, Auerbuch V, Portnoy DA. Bacterial ligands generated in a phagosome are targets of the cytosolic innate immune system. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e51. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada T, et al. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piekna-Przybylska D, Decatur WA, Fournier MJ. The 3D rRNA modification maps database: with interactive tools for ribosome analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D178–D183. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buchmeier NA, Heffron F. Induction of Salmonella stress proteins upon infection of macrophages. Science. 1990;248:730–732. doi: 10.1126/science.1970672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belasco JG. All things must pass: contrasts and commonalities in eukaryotic and bacterial mRNA decay. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:467–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rehwinkel J, Reis e Sousa C. RIGorous detection: exposing virus through RNA sensing. Science. 2010;327:284–286. doi: 10.1126/science.1185068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monroe KM, McWhirter SM, Vance RE. Identification of host cytosolic sensors and bacterial factors regulating the type I interferon response to Legionella pneumophila. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000665. e1000665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nallagatla SR, Toroney R, Bevilacqua PC. A brilliant disguise for self RNA: 5'-end and internal modifications of primary transcripts suppress elements of innate immunity. RNA Biol. 2008;5:140–144. doi: 10.4161/rna.5.3.6839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson BR, et al. Incorporation of pseudouridine into mRNA enhances translation by diminishing PKR activation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:5884–5892. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kariko K, Buckstein M, Ni H, Weissman D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: the impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity. 2005;23:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woodward JJ, Iavarone AT, Portnoy DA. c-di-AMP secreted by intracellular Listeria monocytogenes activates a host type I interferon response. Science. 2010;328:1703–1705. doi: 10.1126/science.1189801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gripenland J, et al. RNAs: regulators of bacterial virulence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:857–866. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raskin DM, Seshadri R, Pukatzki SU, Mekalanos JJ. Bacterial genomics and pathogen evolution. Cell. 2006;124:703–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torchinsky MB, Garaude J, Martin AP, Blander JM. Innate immune recognition of infected apoptotic cells directs T(H)17 cell differentiation. Nature. 2009;458:78–82. doi: 10.1038/nature07781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blander JM, Medzhitov R. Regulation of phagosome maturation by signals from toll-like receptors. Science. 2004;304:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.1096158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutterwala FS, et al. Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity. 2006;24:317–327. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuida K, et al. Altered cytokine export and apoptosis in mice deficient in interleukin-1 beta converting enzyme. Science. 1995;267:2000–2003. doi: 10.1126/science.7535475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sato M, et al. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maurelli AT, Baudry B, d'Hauteville H, Hale TL, Sansonetti PJ. Cloning of plasmid DNA sequences involved in invasion of HeLa cells by Shigella flexneri. Infect Immun. 1985;49:164–171. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.1.164-171.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haraga A, Ohlson MB, Miller SI. Salmonellae interplay with host cells. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:53–66. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schnupf P, Portnoy DA. Listeriolysin O: a phagosome-specific lysin. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1176–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bolstad BM, Irizarry RA, Astrand M, Speed TP. A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:185–193. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/19.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Irizarry RA, et al. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gng015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai M, et al. Evolving gene/transcript definitions significantly alter the interpretation of GeneChip data. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:e175. doi: 10.1093/nar/gni179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saeed AI, et al. TM4: a free, open-source system for microarray data management and analysis. Biotechniques. 2003;34:374–378. doi: 10.2144/03342mt01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saeed AI, et al. TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:134–193. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sartor MA, et al. Intensity-based hierarchical Bayes method improves testing for differentially expressed genes in microarray experiments. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:538. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samarajiwa SA, Forster S, Auchettl K, Hertzog PJ. INTERFEROME: the database of interferon regulated genes. Nucleic acids research. 2009;37:D852–D857. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pahl HL. Activators and target genes of Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors. Oncogene. 1999;18:6853–6866. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coll RC, O'Neill LA. New insights into the regulation of signalling by toll-like receptors and nod-like receptors. J Innate Immun. 2010;2:406–421. doi: 10.1159/000315469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lim SY, Bauermeister A, Kjonaas RA, Ghosh SK. Phytol-based novel adjuvants in vaccine formulation: 2. Assessment of efficacy in the induction of protective immune responses to lethal bacterial infections in mice. Journal of immune based therapies and vaccines. 2006;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1476-8518-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hornung V, et al. 5'-Triphosphate RNA is the ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.