Abstract

Objective

To investigate the criminal pattern in men between 15 and 70 years of age diagnosed with 47,XXY (Klinefelter's syndrome (KS)) or 47,XYY compared to the general population.

Design

Register-based cohort study comparing the incidence of convictions among men with KS and with 47,XYY with age- and calendar-matched samples of the general population. Crime was classified into eight types (sexual abuse, homicide, burglary, violence, traffic, drug-related, arson and ‘others’).

Setting

Denmark 1978–2006.

Participants

All men diagnosed with KS (N=934) or 47,XYY (N=161) at risk and their age- and calendar-time-matched controls (N=88 979 and 15 356, respectively).

Results

The incidence of convictions was increased in men with KS (omitting traffic offenses) compared to controls with a HR of 1.40 (95% CI 1.23 to 1.59, p<0.001), with significant increases in sexual abuse, burglary, arson and ‘others’, but with a decreased risk of traffic and drug-related offenses. The incidence of convictions was significantly increased among men with 47,XYY compared to controls with a HR of 1.42 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.77, p<0.005) in all crime types, except drug-related crimes and traffic. Adjusting for socioeconomic variables (education, fatherhood, retirement and cohabitation) reduced the total HR for both KS and 47,XYY to levels similar to controls, while some specific crime types (sexual abuse, arson, etc) remained increased.

Conclusion

The overall risk of conviction (excluding traffic offenses) was moderately increased in men with 47,XYY or KS; however, it was similar to controls when adjusting for socioeconomic parameters. Convictions for sexual abuse, burglary, arson and ‘others’ were significantly increased. The increased risk of convictions may be partly or fully explained by the poor socioeconomic conditions related to the chromosome aberrations.

Article summary

Article focus

To investigate crime rates of men with an extra sex chromosome (47,XXY and 47,XYY). Based on previous small studies, we hypothesised that an increased crime rate would be present in men with an extra sex chromosome and investigated this in a nationwide registry study.

Key messages

Using a nationwide approach, we show that men diagnosed with KS (47,XXY) and 47,XYY are more frequently convicted for sexual abuse, burglary, arson and other reasons. Traffic offenses are seen less frequently in both groups.

Whether early diagnosis and improved clinical care can lead to a decrease in convictions is not clear.

The increased crime rate may be partly or fully mediated by poor socioeconomic conditions.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The study clearly delineates a pattern of increased crime rates among men diagnosed with an extra sex chromosome. The strength of the present study is the large number of men with sex chromosomes and the large control group and the merging of several registries.

The limitations are that we were not able to control for concomitant medicinal use, especially testosterone use in KS, nor to include clinical data.

Introduction

The sex chromosome trisomies 47,XXY (Klinefelter's syndrome (KS)) and 47,XYY are the most common male sex chromosome aneuploidies compatible with live birth. KS affects 167 per 100 000 men,1–3 while the prevalence estimates of 47,XYY are highly variable, ranging in live born men from 26 per 100 0004 to 375 per 100 000,5 although many are not diagnosed or diagnosed late.6 Both KS and 47,XYY are much more frequent when studied in a tall population,7 which is readily explained by the presence of additional copies of the SHOX gene (and possibly also other genes related to stature) in men with KS and 47,XYY.8 As with 47,XYY, many KS are not diagnosed, and a considerable delay in diagnosis exists for those who get a diagnosis.2

The 47,XYY sex chromosome abnormality has been described in various settings6 9 since the first descriptions of a group of men with 47,XYY in 1965 by Jacobs et al10 who conducted a chromosome survey of male patients at the State Hospital in Carstairs, Scotland, and found that men with the 47,XYY karyotype were particularly frequent among inmates in penal institutions. During the 1960s and 1970s, studies of persons with KS and 47,XYY identified an increased frequency in hospitals for mentally handicapped,11 and men with 47,XYY seemed to be over-represented in prisons.12 Several of these studies reported a general increased rate of criminal behaviour and increased crime rates among both cohorts, especially due to sexual crimes.13 These studies were associated with selection problems as they investigated institutionalised individuals. Two relatively new studies of criminal behaviour among sex chromosome trisomies have been published. Götz et al14 found an increased rate of criminal behaviour among persons with 47,XYY but not among persons with KS. Another study from 198815 linked young KS males with arson. However, both studies include a very limited number of persons. The study by Witkin et al7 in tall persons concluded that there was no evidence of an increased crime rate among KS and 47,XYY, but again with very few study subjects. Long-term follow-up of a cohort of KS (n=19) and 47,XYY (n=19) indicated that persons with 47,XYY had a fourfold increase in convictions, mostly due to minor offenses.16 All investigations conducted so far on this issue are limited by the study of selected groups, either institutionalised or clinic patients, in addition to methodological shortcomings, such as self-report of crimes, poorly defined definition of crime type and poorly defined control groups. All studies have also been conducted in very small groups comprising <20 persons with a chromosome abnormality. The full spectrum of all types of crime has never been reported. As mentioned, diagnosis of both syndromes is usually delayed and more than half of the expected individuals are never diagnosed,2 6 and a more thorough knowledge of all aspects these syndromes would most likely facilitate earlier diagnosis and possibly better clinical care.

In order to examine the crime characteristics of men with KS and 47,XYY, we undertook the present nationwide study, focusing not only on the total number of convictions but also on various crime types. Thus, we investigated the criminal pattern of all men diagnosed with 47,XYY and KS compared with a large age- and calendar-time-matched control group. We compared HRs without and with adjustment for socioeconomic variables in order to assess whether any increased risk of conviction could be explained by the poorer socioeconomic conditions of men with KS and 47,XYY. Furthermore, the criminal pattern before and after the diagnosis of the chromosomal aberration was investigated.

Methods

The present study is a register-based study combining information from the Danish Cytogenetic Central Register, Statistics Denmark and the Danish Central Crime Registry.

Study population

Using the Danish Cytogenetic Central Register, we identified all men diagnosed with a karyotype compatible with KS, 47,XYY or variants thereof in Denmark by January 2009. These men are hereafter referred to as index-persons. The register was founded in 1967 and contains information regarding all cytogenetic analyses performed in Denmark since 1960, including date of diagnosis. Unique identification numbers (ID numbers) from the Civil Registration System enabled identification of every single person diagnosed with an aberrant chromosomal analysis. ID numbers are given to all Danish citizens since 1968. The ID numbers ensured a one-to-one linkage between the registries.

Controls

For each index-person, Statistics Denmark identified up to 100 age- and calendar-time-matched controls (matched on month and year of birth) from the male background population. All dates of emigration and death were retrieved. All controls were alive and living in Denmark when their index-person was diagnosed. All controls emigrated or deceased before the index-person turned 15 years were excluded.

Convictions

The Danish Central Crime Register has previously been described as possibly the most thorough, comprehensive and accurate crime register in the Western world.17 Since the register was digitalised on 1 November 1978, all charges and decisions for any reported offense in Denmark have been registered. We had access to annual information, and a person could be registered with multiple convictions the same year. We defined 1 July the relevant year as the date of the conviction. The study period was from 1 November 1978 to 31 December 2006, as 2006 was last year with available information.

In Denmark, the age of criminal responsibility is 15 years. All solved criminal acts committed by individuals born after 1 November 1963 has been registered in the crime register. We considered only persons between 15 and 70 years during the study period to be at risk of an event. We categorised the offenses into eight groups, that is, (1) sexual-related convictions including rape; (2) homicides; (3) violent convictions; (4) robbery, burglary and theft; (5) traffic offenses; (6) drug-related convictions not including violence; (7) arson and (8) ‘others’.

All convictions of an index-person or a control were retrieved from the crime register. We defined an event as the first conviction in any group and in each of the eight groups separately. Thus, only the first event was analysed, and all succeeding events in the same group were excluded.

We discriminated between events before and after the diagnosis of a chromosome aberration. Also, in order to analyse whether the conviction and the diagnosis could be related, we excluded all convictions up to 2 years before and 2 years after the diagnosis in a separate analysis. We also discriminated between persons diagnosed early and late in life, using the median age at diagnosis as cut-point.

Socioeconomic outcome parameters

From Statistics Denmark, we retrieved information regarding time of the following events, as previously described18: cohabitation with a partner, achievement of an education, fatherhood and retirement.

Cohabitation and marriage

We retrieved all persons' marital and cohabitational status each 1st of January. Data were available from 1980 through 2007. The event was first change from being single to be cohabitating with a partner.

Education

Data were category of education and dates for achieved education. An achieved bachelor degree or higher was considered ‘an education’. The event was first achieved bachelor degree for a person between 18 and 40 years.

Children

All children born or adopted were registered from 1942 until 2007, with a linkage to both of their registered parents. Fatherhood was defined as the event of the first fathering of a child.

Retirement

We defined retirement as due to age, sickness or voluntary choice. A person was considered retired, the first year payment was received due to retirement, regardless of a later return to the labour market.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Statistics

Kaplan–Meier estimates were constructed for time of first conviction. Time at risk started at age of 15 years or at start of registration, whichever came last, and ended at the date of first event, at the age of 70 years, at emigration/death or 31 December 2006, whichever came first.

HRs were calculated using stratified Cox proportional hazards regression, where each case and his matched controls were one stratum. For the analyses, time at risk started on the 15th birthday or 1 November 1978, whichever came last, and time at risk ended 1 July the year we registered an event for the first time, on the date of emigration, on the 70th birthday, on the date of death or 31 December 2006, whichever came first. For analyses before the diagnosis, time at risk ended no later than the date of diagnosis. For analyses after the diagnosis, time at risk started no earlier than the date of diagnosis.

For the analyses excluding all convictions 2 years before and after the diagnosis, all persons who had a first registration of a conviction of the relevant crime type during this period were excluded. We analysed convictions adjusted for cohabitation, education, fatherhood and retirement.

To examine a potential bias associated with undiagnosed KS and 47,XYY cases, we performed a sensitivity analysis, assuming that the risk of conviction among undiagnosed cases is smaller than the risk observed among diagnosed cases, and we applied the statistical uncertainty from the observed data expressed by the SE of the ln(HR) estimate.

All results are shown with 95% CI, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. We made no formal correction for multiple comparisons. We used Stata V.10.0 (Stata Corp.) for all calculations.

Results

We identified 1049 persons with KS, whereof 934 were at risk of an event due to age between 15 and 70 years during the registration period; similarly, 208 persons with 47,XYY were identified, and 161 were at risk of an event. For details on both cohorts of index-persons and their controls, see table 1.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of persons with Klinefelter's syndrome (KS) or 47,XYY

| Karyotype | No. of persons at risk | No. of persons with at least one conviction | Median age at diagnosis (95% CI) | Median year of diagnosis (95% CI) | Median year of birth (95% CI) |

| 47,XXY (KS) | 934 | 385 | 27.7 (26.6 to 28.3) | 1986 (1984 to 1987) | 1961 (1959 to 1962) |

| Controls (KS) | 88 829 | 37 085 | – | – | – |

| 47,XYY | 161 | 80 | 20.6 (17.6 to 23.7) | 1985 (1982 to 1989) | 1969 (1963 to 1971) |

| Controls (47,XYY) | 15 356 | 6284 | – | – | – |

Persons with KS

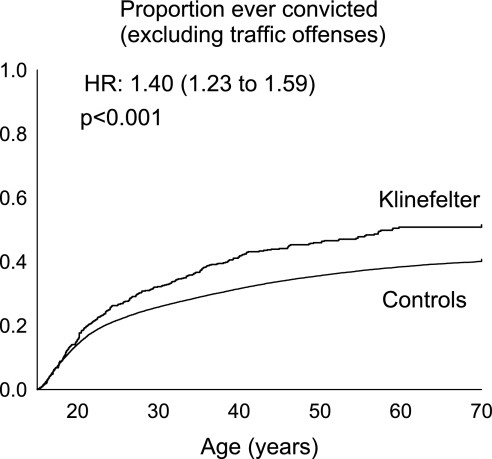

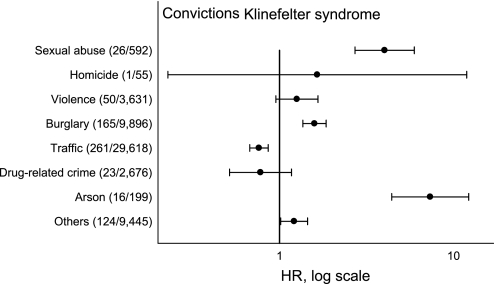

The risk of any conviction was similar in persons with KS and controls with a HR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.05, p=0.28) but was increased to 1.40 (95% CI 1.23 to 1.59) when excluding traffic offenses (table 2). Convictions of sexual abuse, burglary, arson and ‘other’ were moderately increased in persons with KS (figures 1 and 2). When excluding convictions within 2 years before and after the diagnosis, the HRs did not change substantially (supplemental figure 1). The HRs were significantly increased for convictions of sexual abuse, burglary and arson both before and after the KS diagnosis (supplemental table 1). The HRs were lower in the cohort diagnosed late in life (supplemental figure 2). Adjusting for socioeconomic parameters reduced the total HR (excluding traffic offenses) to a HR of 1.05 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.23) (table 2), but it was still significantly increased in the subgroups sexual abuse and arson. The HR for convictions of traffic offenses was significantly decreased both before and after adjustment for socioeconomic parameters.

Table 2.

HRs (95% CI) for overall cause-specific convictions without and with adjustment for education, retirement, cohabitation and fatherhood in men with KS and 47,XYY

| Crude HR | HR with adjustment | |

| KS | 1.40 (1.23 to 1.59)* | 1.05 (0.90 to 1.23)* |

| Sexual abuse | 4.02 (2.71 to 5.95) | 2.74 (1.60 to 4.69) |

| Homicide | 1.65 (0.23 to 11.90) | 4.49 (0.54 to 37.04) |

| Violence | 1.26 (0.95 to 1.66) | 0.88 (0.62 to 1.26) |

| Burglary | 1.59 (1.36 to 1.85) | 1.03 (0.86 to 1.29) |

| Traffic | 0.76 (0.57 to 0.86) | 0.80 (0.69 to 0.93) |

| Drug-related | 0.78 (0.52 to 1.17) | 0.34 (0.20 to 0.60) |

| Arson | 7.35 (4.42 to 12.23) | 5.33 (2.67 to 10.63) |

| ‘Others’ | 1.21 (1.02 to 1.48) | 1.01 (0.81 to 1.26) |

| 47,XYY | 2.09 (1.61 to 2.71)* | 1.04 (0.68 to 1.61)* |

| Sexual abuse | 11.79 (6.46 to 21.52) | 3.66 (1.06 to 12.59) |

| Homicide | 10.36 (1.31 to 81.77) | NA |

| Violence | 2.54 (1.57 to 4.11) | 1.16 (0.51 to 2.63) |

| Burglary | 2.07 (1.47 to 2.91) | 0.93 (0.52 to 1.65) |

| Traffic | 0.95 (0.72 to 1.26) | 0.89 (0.60 to 1.31) |

| Drug-related | 1.74 (0.90 to 3.36) | 0.59 (0.19 to 1.85) |

| Arson | 10.57 (3.76 to 29.76) | NA |

| ‘Others' | 1.89 (1.32 to 2.71) | 1.39 (0.82 to 2.37) |

Total HRs are computed omitting traffic offenses.

KS, Klinefelter's syndrome; NA, a HR could not be computed due to lown.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plot of proportion of persons convicted (excluding traffic offenses) for the first time in the background population (thin line) and in men with Klinefelter's syndrome (bold line). All were 15–70 years of age.

Figure 2.

HRs of convictions due to cause in Klinefelter's syndrome (KS) compared to age-matched men (see the Materials and methods section for details). Actual numbers of offenders (KS/controls) are given in parentheses.

Persons with 47,XYY

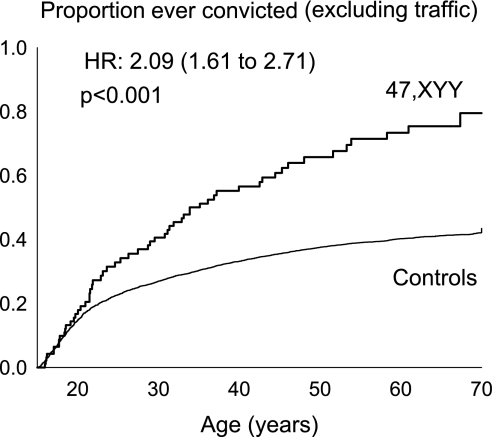

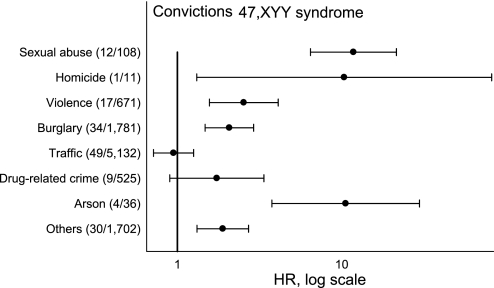

In total, the risk of convictions was moderately increased in persons with 47,XYY compared to controls (HR 1.42 (95% CI 1.14 to 1.77), p<0.005) and even more pronounced (HR 2.09 (95% CI 1.61 to 2.71), p<0.001) when excluding traffic offenses (figure 3 and table 2). A significantly increased HR was identified for convictions of sexual abuse, homicide, violence, burglary, arson and ‘others’ (figure 4). In none of the eight conviction groups did the estimate change substantially when excluding convictions 2 years before or after the diagnosis (supplemental figure 3). Before the diagnosis, the HRs were significantly increased for convictions of sexual abuse only, and there were no events among the persons with 47,XYY in homicides, drug-related convictions and the arson group (supplemental table 1). After the diagnosis, the HRs were significantly increased in all offense groups, except for the traffic offenses (data not shown). There were no significant differences between HRs for those diagnosed younger and older than the median age at diagnosis (supplemental figure 4). Adjusting for socioeconomic parameters reduced the total HR (excluding traffic offenses) to 1.04 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.61) (table 2), and all other subgroup HRs but sexual abuse decreased.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of proportion of persons convicted (excluding traffic offenses) for the first time in the background population (thin line) and in men with 47,XYY (bold line). All were 15–70 years of age.

Figure 4.

HRs of convictions due to cause in 47,XYY syndrome compared to age-matched men (see the Materials and methods section for details). Actual numbers of offenders (47,XYY/controls) is given in parentheses.

Discussion

This large study in persons with KS and 47,XYY covering all diagnosed individuals in Denmark demonstrates that persons with 47,XYY and KS are convicted of a number of specific offenses more frequently than the background population. The total number of convictions, however, was not increased in persons with KS, primarily due to a significantly decreased number of traffic-related convictions. The study also demonstrates that unfavourable socioeconomic conditions may be part of the explanation for the increased rate of convictions since adjustment for socioeconomic variables reduced the HR in both cohorts. We could also demonstrate an association between convictions and age at diagnosis in persons with KS, that is, the earlier the diagnosis had been made, the greater the likelihood of having been convicted of an offense.

Men with KS and 47,XYY are to a large extent diagnosed late or not diagnosed at all,2 6 and we have previously estimated that only 25% of KS and 15% of 47,XYY get a diagnosis. The same pattern is seen in other countries.19 20 Thus, the results of the present study apply to the studied cohort—in other words, patients with KS and 47,XYY seen in daily clinical practice, and risk estimates may therefore not be applicable to groups of yet undiagnosed men with sex chromosome trisomies or even patients from other countries. We are well aware that the results of the present study may stigmatise persons with KS and 47,XYY due to the over-representation of convictions of sexual abuse and arson. But instead of suppressing such data, we believe that they are pivotal in furthering the understanding of these syndromes.

We found a significantly increased cause-specific risk of convictions due to sexual abuse, burglary, arson and ‘others’ among men with 47,XYY and KS. Furthermore, the cause-specific risk of convictions due to homicide and violence was increased among persons with 47,XYY. We then studied the impact of socioeconomic factors by adjusting for level of education, fatherhood, retirement and cohabitation. This adjustment lead to reductions in most HR, and only the risk of convictions for sexual abuse and arson among persons with KS and only sexual abuse among persons with 47,XYY remained significantly elevated. Among persons with KS, we found a significantly decreased risk of traffic-related convictions.

In general, information about sexual function in men with sex chromosome aberrations is sparse. Schiavi et al21 found that fewer men with 47,XYY, but not men with KS, were married, experienced greater sexual dissatisfaction in general, acknowledged unconventional sexual experiences compared to a control group and demonstrated a less masculine gender role. Furthermore, men with 47,XYY have been described as immature, having interpersonal and sexual difficulties.22 Thus, men with KS and 47,XYY have been described with increased frequency of different or deviating sexual behaviour, although it is important to stress that only few and small studies have investigated this subject. In addition, an increased vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and deviant behaviour,23–25 psychophysiological dysfunction26 and increased levels of autism traits in KS27 28 together with a lower educational level and poor socioeconomic status18 may result in a increased susceptibility to commit a crime. We did not expect the finding of significantly increased risk of convictions for sexual abuse, and we believe this to be of considerable importance. The reason for the increased frequency of sexual abuse convictions is of course speculative but may be due to the previously described feeling of being sexually different, which may end up in misinterpreting sexual cues, or possibly frustration leading to socially and legally unacceptable ways of achieving sexual satisfaction. Further studies are needed to clarify whether early diagnosis, sex steroid treatment, psychological therapy or other initiatives may alter this finding.

Our findings of an increased frequency of convictions other than traffic offenses were not corroborated by the long-term follow-up study by Ratcliffe,16 who only found increased criminality among persons with 47,XYY (n=19), but not among persons with KS (n=19), and that this increase primarily was due to minor offenses.

Previous reports have linked persons with KS with arson,15 29 and a case report identified improvement on treatment for hypergonadotropic hypogonadism.30 There have only been case reports of arson in men with 47,XYY.14 31 We have no specific explanation as to why this specific tendency is present, but it is possible that some of the psychopathological traits mentioned above, especially for the KS group, may prove explanatory in future studies.

Previously, lower intelligence has been pointed out as a contributing factor to the increased criminal behaviour in men with 47,XYY.14 Götz et al14 investigated criminality and antisocial behaviour in unselected men with KS and 47,XYY and showed that men with 47,XYY were more likely to have a criminal record compared to controls and found this to be due to lower IQ (n=16). They found no increase in the number of criminal records among persons with KS compared with controls, possibly due to low power (n=13).14 Witkin et al7 found a significantly increased rate of criminality in 47,XYY (n=12) even after adjusting for social class and intelligence, while the crime rate among KS (n=16) after adjustment was similar to the background population.

We did find that the association between the crime rate (excluding traffic offenses) and either KS or 47,XYY was reduced when adjusting for socioeconomic variables, such as level of education, retirement, cohabitation and fatherhood. In other words, the increased risk of conviction among the cases may partly or fully be explained by disadvantageous socioeconomic conditions. However, although there may be a relationship between increased convictions and poor socioeconomic status in persons with sex chromosomal abnormal phenotype, the causal relationship cannot be established.

We matched the current large group of patients with approximately 100 controls for each case. We did not match on other variables, such as socioeconomic factors, since these factors could easily be causally involved in how the chromosome abnormality leads to a deviant pattern of criminality. Indeed, matching on socioeconomic factors would likely lead to overmatching—which ‘is potentially capable of biasing study results beyond any hope of repair’.32 The current approach allowed us to use subsequent adjustments to clarify whether socioeconomic factors were involved, which they in fact turned out to be. We did correct for level of education, fatherhood, retirement and cohabitation, although it can be problematic to control for social factors, because the chromosome aberrations per se can be the very reason for social problems, while the reverse is not possible. In addition, social problems—marginalisation, lack of education, poverty, etc—can affect the risk of criminal behaviour and of being detected and convicted. In other words, social problems may be part of a chain of events and adjustment would therefore introduce confounding. However, having controlled for these factors, we found that the total HRs for being convicted decreased and were no longer statistically significant for either group. Being well aware of the deviant behaviour and learning difficulties present in both cohorts from a very young age, we hypothesise that these difficulties are part of the background for the identified increased number of convictions. We then performed a sensitivity analysis to examine a potential bias arising if the severity of the syndrome affects both the risk of conviction and the probability of being diagnosed.33 In one analysis, we assumed that the excess hazard among undiagnosed cases was half the excess hazard seen among diagnosed cases, and we applied the statistical uncertainty from the observed data. In another similar analysis, we assumed that the excess hazard among undiagnosed cases was similar to that in the background population. For KS, we assumed that 25% of all cases had been diagnosed. In the sensitivity analyses, the HRs were reduced, but still significantly elevated for all convictions (excluding traffic offenses), and for sexual abuse, burglary and arson (supplementary table 2). For 47,XYY, we observed a similar pattern. Here, we assumed that 15% of all cases had been diagnosed. In the sensitivity analysis, the HRs were reduced, but still significantly elevated for all convictions (excluding traffic offenses), and for sexual abuse, violence, burglary and arson (supplementary table 2). In other words, it is highly likely that the crime rate would remain significantly increased in an entirely unbiased population of both KS and 47,XYY with complete diagnosis of all cases.

We identified an association between age at diagnosis and convictions in some groups in both cohorts. The findings of a more ‘normal’ number of convictions in persons with KS in those diagnosed when older than the median age of diagnosis might be explained by a less typical phenotype, both physical and, perhaps more importantly, cognitive phenotype. However, this finding was not present in the persons with 47,XYY. We find no reason to believe that a late diagnosis per se is positive. Due to the reported increased criminal problems, we undertook analyses excluding those convicted in close proximity to the diagnosis. We hereby intended to avoid detection bias by excluding those who were diagnosed due to a conviction and who may bias the results towards an increased number of convictions in the index-persons. As exclusion of such persons hardly changed the findings, we believe that this type of bias can be ignored. The drawback of this study is the lack of clinical information, including IQ level, treatment with sex steroids, number of persons with a driving license and access to a car and for instance psychiatric diagnoses. The advantages are the nationwide inclusion of all diagnosed men at risk with sex chromosome trisomies and the close matching of the controls.

We were not able to control for concomitant medicinal use. There are usually no known hormonal deficits among men with 47,XYY, while men with KS often receive testosterone substitution therapy due to hypergonadotrophic hypogonadism. It has been speculated that early testosterone substitution in KS34 35 would partially attenuate the impact of the syndrome on intellectual functioning and possibly other factors, but this remains to be studied. Others have speculated that testosterone substitution therapy could cause psychological disturbances, such as aggressive behaviour and occasionally lead to violent crime, especially at supraphysiological doses,36 although a placebo controlled study of androgen treatment in healthy young men showed no or minimal change in mood or behaviour.37 38 We cannot fully exclude the possibility that the pattern of criminality among KS could be related to testosterone substitution therapy, while it seems unlikely that medicinal use among men with 47,XYY is related to criminality. We note that the pattern of criminality in 47,XYY, who have a normal testosterone production, was equal or higher than among KS, and furthermore that criminality among KS was elevated even before diagnosis and thus before commencement of supplementation with testosterone, making it unlikely that testosterone supplementation is causally involved in the excess criminality in KS. In addition, in many men with KS, conventional testosterone supplementation is often not sufficient, and many men with KS are also not compliant, at least not all the time, resulting in hypotestosteronemia, elevated luteinizing hormone and diseases, symptoms and signs related to hypogonadism.39–41

In conclusion, this study on all diagnosed men with a sex chromosome trisomy in Denmark identified a significantly increased number of convictions, excluding traffic offenses, both in persons with KS and 47,XYY. When adjusting for socioeconomic factors, the adjusted risk was similar to controls for both cohorts. We interpret this as indicating that a main explanation of the increased risk of conviction is due to unfavourable living conditions associated with these syndromes. In both cohorts, we found a significantly increased number of convictions due to sexual offense and arson. Further studies are needed to identify whether these findings can be prevented by improved clinical care, including earlier diagnosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

KS had full access to all the data in the study, and KS and CHG take responsibility for the integrity of the data, the accuracy of the data analysis and the decision to publish.

Footnotes

To cite: Stochholm K, Bojesen A, Jensen AS, et al. Criminality in men with Klinefelter's syndrome and XYY syndrome: a cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000650. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000650

Contributors: KS, AB, SJ and CHG participated in the conception and design of the study. KS, AB, SJ, ASJ and CHG participated in the analysis and interpretation of data. KS and CHG drafted the article, and KS, AB, SJ, ASJ and CHG approved the final version to be published.

Funding: Funded by Central Region Denmark; Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, grant number 1-45-72-7-07; 271-09-0907.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data from the present study available.

References

- 1.Nielsen J, Wohlert M. Sex chromosome abnormalities found among 34,910 newborn children: results from a 13-year incidence study in Arhus, Denmark. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser 1990;26:209–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bojesen A, Juul S, Gravholt CH. Prenatal and postnatal prevalence of Klinefelter syndrome: a national registry study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:622–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Handelsman DJ. Update in andrology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:4505–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goad W, Robinson A, Puck T. Incidence of aneuploidy in a human population. Am J Hum Genet 1976;28:62–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sergovich F, Valentine GH, Chen AT, et al. Chromosome aberrations in 2159 consecutive newborn babies. N Engl J Med 1969;280:851–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stochholm K, Juul S, Gravholt CH. Diagnosis and mortality in 47, XYY persons: a registry study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2010;5:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Witkin HA, Mednick SA, Schulsinger F, et al. Criminality in XYY and XXY men. Science 1976;193:547–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ottesen AM, Aksglaede L, Garn I, et al. Increased number of sex chromosomes affects height in a nonlinear fashion: a study of 305 patients with sex chromosome aneuploidy. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152A:1206–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bender BG, Puck MH, Salbenblatt JA, et al. The development of four unselected 47, XYY boys. Clin Genet 1984;25:435–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacobs P, Brunton M, Melville M, et al. Aggressive behavior, mental sub-normality and the XYY male. Nature 1965;208:1351–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price W, Whatmore P. Behaviour disorders and pattern of crime among XYY males identified at a maximum security hospital. Br Med J 1967;1:533–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finley W, McDanal CJ, Finley S, et al. Prison survey for the XYY karyotype in tall inmates. Behav Genet 1973;3:97–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schroder J, de la Chapelle A, Hakola P, et al. The frequency of XYY and XXY men among criminal offenders. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1981;63:272–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Götz MJ, Johnstone EC, Ratcliffe SG. Criminality and antisocial behaviour in unselected men with sex chromosome abnormalities. Psychol Med 1999;29:953–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller ME, Sulkes S. Fire-setting behavior in individuals with Klinefelter syndrome. Pediatrics 1988;82:115–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratcliffe S. Long-term outcome in children of sex chromosome abnormalities. Arch Dis Child 1999;80:192–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodgins S, Mednick SA, Brennan PA, et al. Mental disorder and crime. Evidence from a Danish birth cohort. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1996;53:489–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bojesen A, Stochholm K, Juul S, et al. Socioeconomic trajectories affect mortality in Klinefelter syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96:2098–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins CD, Swerdlow AJ, Schoemaker MJ, et al. Mortality and cancer incidence in males with Y polysomy in Britain: a cohort study. Hum Genet 2007;121:691–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swerdlow AJ, Higgins CD, Schoemaker MJ, et al. Mortality in patients with Klinefelter syndrome in Britain: a cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:6516–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiavi RC, Theilgaard A, Owen DR, et al. Sex chromosome anomalies, hormones, and sexuality. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nielsen J, Christensen AL, Schultz-Larsen J, et al. A psychiatric-psychological study of patients with the XYY syndrome found outside of institutions. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1973;49:159–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bojesen A, Juul S, Birkebaek NH, et al. Morbidity in Klinefelter syndrome: a Danish register study based on hospital discharge diagnoses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;91:1254–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bruining H, Swaab H, Kas M, et al. Psychiatric characteristics in a self-selected sample of boys with Klinefelter syndrome. Pediatrics 2009;123:e865–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeLisi LE, Maurizio AM, Svetina C, et al. Klinefelter's syndrome (XXY) as a genetic model for psychotic disorders. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2005;135:15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rijn S, Swaab H, Magnee M, et al. Psychophysiological markers of vulnerability to psychopathology in men with an extra X chromosome (XXY). PLoS One 2011;6:e20292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rijn S, Swaab H, Aleman A, et al. Social behavior and autism traits in a sex chromosomal disorder: Klinefelter (47XXY) syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:1634–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tartaglia N, Cordeiro L, Howell S, et al. The spectrum of the behavioral phenotype in boys and adolescents 47, XXY (Klinefelter syndrome). Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2010;8(Suppl 1):151–9 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eytan A, Paoloni-Giacobino A, Thorens G, et al. Fire-setting behavior associated with Klinefelter syndrome. Int J Psychiatry Med 2002;32:395–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eberle AJ. Klinefelter syndrome and fire-setting behavior. Pediatrics 1989;83:649–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowen P, Mullen PE. An XYY man. Br J Psychiatry 1979;135:78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Design strategies to improve study accuracy. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland KS, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Willians & Wilkins, 2008:168–82 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenland S, Lash TL. Bias analysis. In: Rothman KJ, Greenland KS, Lash TL, eds. Modern Epidemiology. 3rd edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Willians & Wilkins, 2008:345–80 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson JL, de la Cruz F, Swerdloff RS, et al. Klinefelter syndrome: expanding the phenotype and identifying new research directions. Genet Med 2003;5:460–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross JL, Samango-Sprouse C, Lahlou N, et al. Early androgen deficiency in infants and young boys with 47, XXY Klinefelter syndrome. Horm Res 2005;64:39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pope HG, Jr, Kouri EM, Powell KF, et al. Anabolic-androgenic steroid use among 133 prisoners. Compr Psychiatry 1996;37:322–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Handelsman DJ. Androgen misuse and abuse. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;25:377–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pope HG, Jr, Kouri EM, Hudson JI. Effects of supraphysiologic doses of testosterone on mood and aggression in normal men: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:133–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aminorroaya A, Kelleher S, Conway AJ, et al. Adequacy of androgen replacement influences bone density response to testosterone in androgen-deficient men. Eur J Endocrinol 2005;152:881–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bojesen A, Kristensen K, Birkebaek NH, et al. The metabolic syndrome is frequent in Klinefelter's syndrome and is associated with abdominal obesity and hypogonadism. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1591–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bojesen A, Birkebaek N, Kristensen K, et al. Bone mineral density in Klinefelter syndrome is reduced and primarily determined by muscle strength and resorptive markers, but not directly by testosterone. Osteoporos Int 2011;22:1441–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.