Abstract

Palladium-catalyzed cross coupling conditions were developed that efficiently afford 2-aryl-2-nitroacetates from aryl bromides and the very acidic nitroacetates.

Formation of C–C bonds via metal-catalyzed cross-couplings has become a broadly useful tool for the construction of organic molecules. In the redox neutral variant (i.e. Stille, Negishi, Kumada, Suzuki, etc.) many nucleophiles have been successfully coupled with a range of halide electrophiles.1 In addition, numerous obstacles, such as metal coordination and cross-reactivity, have also been overcome in the coupling of nucleophiles generated in situ from acidic species. For example, thiolation of aryl halides was one of the first intermolecular cross-couplings involving in situ nucleophile formation.2,3 Subsequently, Hartwig and Buchwald were the first to cross-couple aryl halides with amines and alcohols without the need to preform the corresponding stannyl nucleophiles.4,5 Concurrently, reductive elimination utilizing softer carbon nucleophiles was being accomplished. Intermolecular cyanoacetate coupling with phenylbromide was first reported in 1985.5,6 Since then couplings have been expanded to include α -arylation of ketones, azlactones, glycine imines, 1,3-dicarbonyls, sulfones, imines, sulfoximines, and nitroalkanes.7

In this communication, we describe a parallel microscale experimentation (PME) approach to discover suitable conditions for the hitherto unreported coupling of nitroacetates with aryl bromides to generate 2-aryl-2-nitroacetates (Scheme 1). There are few reports8 on the synthesis of 2-aryl-2-nitroacetates, highlighting a need for development in this area.

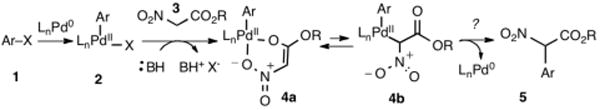

Scheme 1.

Nitroacetate coordination to palladium.

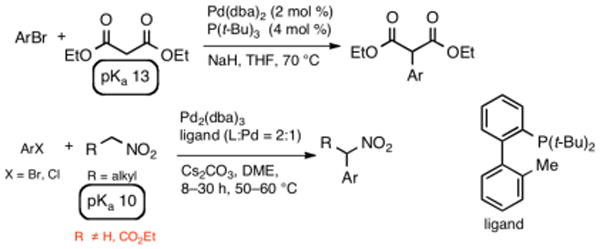

The higher acidity of nitroacetates (pKa 5.8)9 combined with a disposition toward chelation poses a new set of challenges in cross-coupling with aryl halides compared to similar activated methylene compounds such as acyclic 1,3-dicarbonyls (pKa 9-13) and nitroalkanes (pKa 10) (Scheme 2).10–12 This high acidity would lead to the expectation that only a very mild base would be needed. However, the resultant anion is a very poor nucleophile and is poised to form highly favorable O,O′-bound intermediates such as 4a (Scheme 1). Rearrangement to the C-bound form 4b, a prerequisite for C-C reductive elimination and formation of 5,11 would require considerable reorganization and potentially the participation of a second ligand. Initial trials utilizing NaH with tris-tert-butylphosphine and with Pd2dba3 as reported for the related malonates10a (Scheme 2) were unsuccesful (Table 1, entry 1). Reasoning that milder bases could be used, a range of alternate bases was examined to no avail (entries 2-5). To determine if the reductive elimination step was problematic, a more electron-rich aryl bromide was utilized, but no improvement was seen (entries 6-7). Finally, the optimal ligand for nitroalkanes12a (Scheme 2) was studied with similar poor results (entry 8).

Scheme 2.

Hartwig's coupling of malonates and Buchwald's coupling of nitroalkanes.

Table 1.

Initial benchtop results (eq 1).a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | R | base | solvent | ligand | conversionb (%) |

| 1 | H | NaH | THF | P(t-Bu)3 | 0 |

| 2 | H | Cs2CO3 | THF | P(t-Bu)3 | 0 |

| 3 | H | Cs2CO3 | DME | P(t-Bu)3 | 7 |

| 4 | H | CsHCO3 | DME | P(t-Bu)3 | 2 |

| 5 | H | NaOAc | DME | P(t-Bu)3 | 4 |

| 6 | OMe | CsHCO3 | toluene | P(t-Bu)3 | 3 |

| 7 | OMe | NaOAc | toluene | P(t-Bu)3 | 7 |

| 8 | H | Cs2CO3 | toluene | t-BuMePhos | 6 |

Reaction conditions: Pd2dba3 (2.5 mol %), nitroacetate (2 equiv), aryl bromide (1 equiv), base (1.2 equiv), and solvent (0.2 M).

Determined by 1H NMR with repsect to ethyl nitroacetate starting material.

While the preliminary results secured that conversion of 2 to 5 is achievable, it was clear that the conditions highly effective for malonates and nitroalkanes were not translatable to nitroacetates. Since our understanding of how the reaction variables effect the mechanism was incomplete, a range of palladium sources, ligands, and bases needed to be examined. To effectively complete this study, parallel microscale experimentation was utilized.13 By using 1-mL vials with 100 μL reaction volumes at 0.2 M concentration (4.4 μL nitroacetate per vial), it was straightforward to undertake 96 reactions in a single plate. In addition to contributing to efficiency (3 d total time time for set-up, reaction and analysis), only 422 μL (3.84 mmol) of nitroacetate was needed to screen 96 sets of conditions.

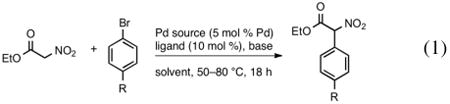

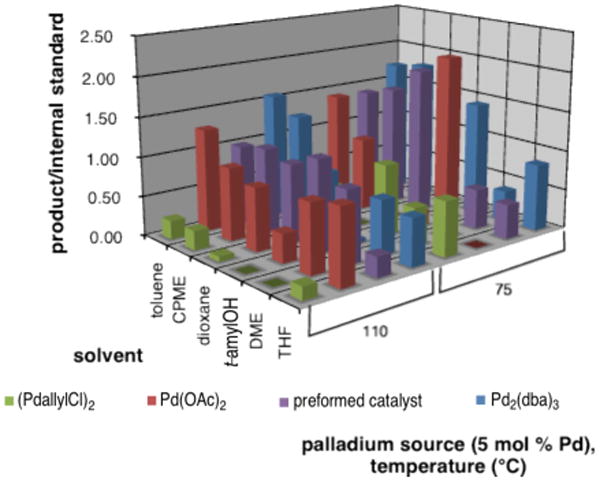

Based upon the results in Table 1 an unbiased screen of various phosphines (monodentate, bidentate, hindered, biphenyl, etc.) was undertaken at 75 °C in combination with two palladium sources and four bases spanning a broad pKa range (Figure 1). The conversion as indicated by the product/internal standard ratio is illustrated in the 3-D plot in Figure 1. Table 2 lists the top screening results along with selected isolated yields when performed on a larger scale.

Figure 1.

Graphical summary of PME screen #1 (eq 1, R = H, T = 75 °C)

Table 2.

Top screening results from PME screen #1 and scale up (eq 1, R = H).

| entry | ligand | Pd | base | solvent | product/ISa, yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | t-BuXPhos | Pd2dba3 • CHCl3 | CsHCO3 | toluene | 6.9, 93% |

| 2 | t-BuXPhos | (allylPdCl)2 | CsHCO3 | DME | 5.1, 46% |

| 3 | Me4t-Bu XPhos | Pd2dba3 • CHCl3 | Cs2CO3 | toluene | 4.5, N/Ac |

| 4 | Me4t-BuXPhos | Pd2dba3 • CHCl3 | CsHCO3 | toluene | 3.7, N/Ac |

| 5 | t-BuXPhos | (allylPdCl)2 | K3PO4 | DME | 3.0, N/Ad |

| 6 | Me4t-BuXPhos | (allylPdCl)2 | Cs2CO3 | DME | 1.8, N/Ad |

| 7 | t-BuXPhos | (allylPdCl)2 | Cs2CO3 | DME | 1.8, 53% |

| 8 | Me4t-BuXPhos | (allylPdCl)2 | CsHCO3 | DME | 1.04, N/Ad |

Relative conversions from screen (IS = internal standard).

Isolated yields upon scale up (0.25 mmol scale).

Not isolated because conversion by 1H NMR was low.

Not scaled up.

This screen revealed that only three ligands, BrettPhos L10, Me4 t-BuXPhos L15, and t-BuXPhos L14 (Figure 1) provided any product with the latter two proving superior. Di-tert-butyl substituted biphenylphosphine ligands seem to be superior for cross-couplings of weak nucleophiles as seen here and in other reports.14,15 In this case, this narrow window suggests that the biphenyl η-1 coordination15 is critical to forming a reactive species. In addition, blocking of palladacycle formation with the isopropyl groups is necessary.15 Most surprising was the narrow range of sterically acceptable ligands with the smaller XPhos L9 failing while the two methoxy groups of BrettPhos L10 offset the smaller phosphine cyclohexyl substituents (L9 < L10 ≪ L15 < L14). On the other end, Me4 t-BuXPhos L15 appears too large.

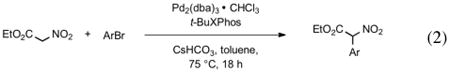

Holding the t-BuXPhos (L14) ligand and the CsHCO3 base constant, further parallel microscale experimentation was undertaken to identify the optimal temperature, Pd source, and solvent (Figure 2). On the whole, lower temperatures (75 °C versus 110 °C) provided better results, presumably due to product decomposition at the higher temperature. With every solvent combination, Pd2dba3 · CHCl3 and a preformed palladacycle containing the optimal t-BuXPhos ligand {chloro(2-di-tert-butylphosphino-2′,4′,6′-trisisopropyl-1,1′-biphenyl)[2-(2-aminoethyl)phenyl] palladium(II)}17 gave consistent results, whereas [(allyl)PdCl]2 and Pd(OAc)2 were less consistent. Upon scale up, Pd2dba3 · CHCl3 provided high isolated yields (93%) with the preformed catalyst being less effective (88%). In line with the initial screening results, the next most effective palladium source was [(allyl)PdCl]2 whereas Pd(OAc)2 was significantly poorer. Reaction was observed in most of the solvents with the nonpolar solvents (toluene and cylopentyl methyl ether) performing better than polar solvents (dioxane, DME, tert-amyl alcohol, THF).

Figure 2.

Graphical summary of PME screen #2 results (eq 1, R = H, base = CsHCO3, ligand = t-BuXPhos) (CPME = cyclopentyl methyl ether, t-amylOH = tert-amyl alcohol).

Further experiments indicated that a 2:1 ligand:palladium ratio was the most effective, in line with other results with enolates.10,12 As expected for this reaction where deprotonation of the nitroacetate is a key step, a base was cruical to the success of the process (Table 3, entry 1). An examination of bases (Table 3) found that relative to CsHCO3 (entry 2) stronger bases (K3PO4, Cs2CO3, Figure 1; CsOH, NaOt-Bu, entries 3-4) were not as successful. Presumably, stronger bases generate larger amounts of the nitroacetate anion, which is not very soluble.10a Bases with harder cations (KHCO3, NaHCO3, Li2CO3, entries 5-7) provided little or no product formation, either due to lower solubility or greater bonding to the nitronate anion, which would impede ligand exchange. On the other end of the spectrum, even softer counterions (Rb2CO3, entry 8) performed similarly relative to cesium. CsF (entry 9) with the optimal counterion and a similar pKa relative to CsHCO3 was effective, but less so, indicating that the fluoride anion may remain involved. A variety of amine bases were completely ineffective (entries 10–13).

Table 3.

Benchtop screen of bases (eq 1, R = H).a

| entry | base | conversionb(%), yieldc(%) | entry | base | conversionb (%), yieldc(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | 0, 0 | 8 | Rb2CO3 | 100, 90 |

| 2 | CsHCO3 | 100, 93 | 9 | CsF | 60, 60 |

| 3 | CsOH | 41, N/Ad | 10 | (i-Pr)2NEt | 0, 0 |

| 4 | NaOt-Bu | 0, 0 | 11 | DMAP | 0, 0 |

| 5 | KHCO3 | 19, N/Ad | 12 | 2,6-(t-Bu)2-4-MePy | 0, 0 |

| 6 | NaHCO3 | 0, 0 | |||

| 7 | Li2CO3 | 0, 0 | 13 | DBU | 10, N/Ad |

Reaction conditions: Pd2dba3 • CHCl3 (2.5 mol %), nitroacetate (2 equiv), aryl bromide (1 equiv), base (1.2 equiv), and toluene (0.2 M) at 75 °C.

Conversion by 1H NMR with respect to remaining ethyl nitroacetate.

Isolated yields.

Not isolated.

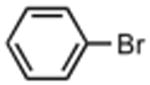

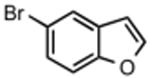

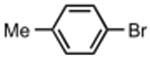

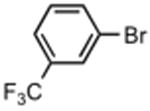

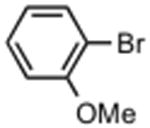

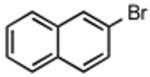

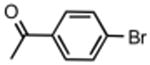

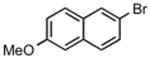

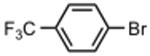

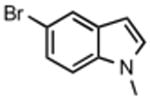

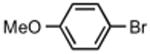

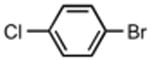

The best reaction conditions were 2.5 mol % Pd2dba3·CHCl3, 10 mol % t-BuXPhos, 1.2 equiv CsHCO3 in toluene at 75 °C, which afforded the products from various aryl bromides and ethyl nitroacetate in isolated yields of 52-96% (Table 4). Notably, electron-rich and electron-poor aryl halides reacted well reinforcing the notion that oxidative addition is not the problematic step in the reaction pathway. In addition, heterocyclic compounds (entries 7 and 11) could be employed. Interestingly, ketones did not undergo competing reaction with the nitroacetate anion (entry 4). Reaction selectivity for aryl bromides over aryl chlorides was observed (entry 12) with only a small amount of the dicoupled product isolated (16%).

Table 4.

Reaction of ethyl nitroacetate with aryl bromides (eq 2).a

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | aryl bromide | yield (%) | entry | aryl bromide | yield (%) |

| 1 |

|

93 | 7 |

|

52 |

| 2 |

|

79 | 8 |

|

80 |

| 3b |

|

69 | 9 |

|

77 |

| 4 |

|

96 | 10 |

|

76 |

| 5 |

|

71 | 11 |

|

95 |

| 6 |

|

81 | 12 |

|

61 |

Reaction conditions: 5 mol % Pd, 10 mol % ligand, ethyl nitroacetate (2 equiv), aryl bromide (1 equiv), CsHCO3 (1.2 equiv), and toluene (0.2 M).

20 mol % Pd.

On the other hand, the method was not suitable for aryl iodides, triflates, and chlorides. Since such species undergo oxidative addition under these conditions, we speculate that the nature of the counterion is critical to the transmetallation of 3 to 4 (Scheme 2) in line with related reports on other enolates.18

While moderately hindered aryl bromides couple (Table 4, entry 3), more hindered compounds such as 1-bromonaphthalene or ortho-bromotoluene were not successful. Hartwig and Culkin notice this downfall in the α-arylation of ketones11 and propose it arises from the inability of the O,O-bound palladium intermediate 4a to rearrange to the carbon-bound intermediate 4b, an already difficult proposition in this system (Scheme 1).

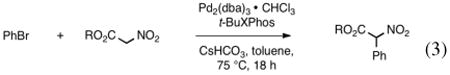

To further probe the reactivity of this system methyl, tert-butyl, and benzyl nitroacetates were synthesized.19 These nitroacetate couplings afforded product in moderate to good yields (Table 5). The increased tendency of methyl nitroacetate to hydrolyze and decarboxylate lowers the isolated yield (entry 1).

Table 5.

Reaction of various nitroacetates with bromobenzene (eq 3).a

| ||

|---|---|---|

| entry | R | yield (%) |

| 1 | Me | 53 |

| 2 | Et | 93 |

| 3 | t-Bu | 88 |

| 4 | Bn | 95 |

Reaction conditions: 5 mol % Pd, 10 mol % t-BuXPhos, nitroacetate (2 equiv), aryl bromide (1 equiv), CsHCO3 (1.2 equiv), and toluene (0.2 M).

In summary, we have developed conditions for the catalytic cross coupling of nitroacetates with aryl bromides to generate 2-aryl-2-nitroacetates. A key requirement in the palladium catalyzed coupling is the use of tBuXPhos as ligand, which is likely a result of the high acidity of the nitroacetate substrate as well as O,O′-chelation competing with C-coordination to palladium. An improved understanding of ligand requirements is critical to the more rapid development of these important processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Trung Cao for training on the Penn Merck PME equipment (NSF GOALI CHE0848460) and are grateful to the NIH (RO1GM087605) for financial support. Partial instrumentation support was provided by the NIH for MS (1S10RR023444) and NMR (1S10RR022442).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Contributor Information

Spencer D. Dreher, Email: spencer_dreher@merck.com.

Marisa C. Kozlowski, Email: marisa@sas.upenn.edu.

References

- 1.For a recent review refer to: Jana R, Pathak TP, Sigman MS. Chem Rev. 2011;111:1417–1492. doi: 10.1021/cr100327p.

- 2.For a recent review of cross coupling to form C-S bonds refer to: Eichman CC, Stambuli JP. Molecules. 2011;16:590–608. doi: 10.3390/molecules16010590.

- 3.Kosugi M, Shimizu T, Migita T. Chem Lett. 1978:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.For a recent review of C-O bond formation via reductive elimination refer to: Enthaler S, Company A. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:4912–4924. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15085e.

- 5.For select recent reviews of reductive elimination to form a carbon heteroatom bond refer to: Sadig JER, Willis MC. Synthesis. 2011;1:1–22.Hartwig J. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:852–860.

- 6.Uno M, Seto K, Ueda W, Masuda M, Takahashi S. Synthesis. 1985;5:506–508. [Google Scholar]

- 7.For recent reviews refer to: Bellina F, Rossi R. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1082–1146. doi: 10.1021/cr9000836.Johansson CCC, Colacot TJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:676–707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903424.

- 8.a) Lehr F, Gonnermann J, Seebach D. Helv Chem Acta. 1979;62:2258–2275. [Google Scholar]; b) Ram S, Ehrenkaufer RE. Synthesis. 1986;16:133–135. [Google Scholar]; c) Hugener M, Heimgartner H. Helv Chim Acta. 1995;78:1490–1498. [Google Scholar]; d) Kozyrod RP, Pinhey JT. Aust J Chem. 1985;38:713–721. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adolph HG, Kamlet MJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1966;88:4761–4763. [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Beare NA, Hartwig JF. J Org Chem. 2002;67:541–555. doi: 10.1021/jo016226h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fox JM, Huang X, Chieffi A, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:1360–1370. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartwig JF, Culkin DA. Acc Chem Res. 2003;36:234–245.9. doi: 10.1021/ar0201106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Vogl EM, Buchwald SL. J Org Chem. 2002;67:106–111. doi: 10.1021/jo010953v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Muratake H, Nakai H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2355–2358. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreher SD, Dormer PG, Sandrock DL, Molander GA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:9257–9259. doi: 10.1021/ja8031423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosen BR, Ruble JC, Beauchcamp TJ, Navarro A. Org Lett. 2011;13:2564–2567. doi: 10.1021/ol200660s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barder TE, Walker SD, Martinelli JR, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:4685–4696. doi: 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Burgos CH, Barder TE, Huang X, Buchwald SL. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2006;45:4321–4326. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Johansson CCC, Colacot TJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:676–707. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biscoe MR, Fors BP, Buchwald SL. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6686–6687. doi: 10.1021/ja801137k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liao X, Weng Z, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:195–200. doi: 10.1021/ja074453g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanier SF, Larouche G, Wurz RP, Charette AB. Org Lett. 2010;12:672–675. doi: 10.1021/ol9026528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.