Abstract

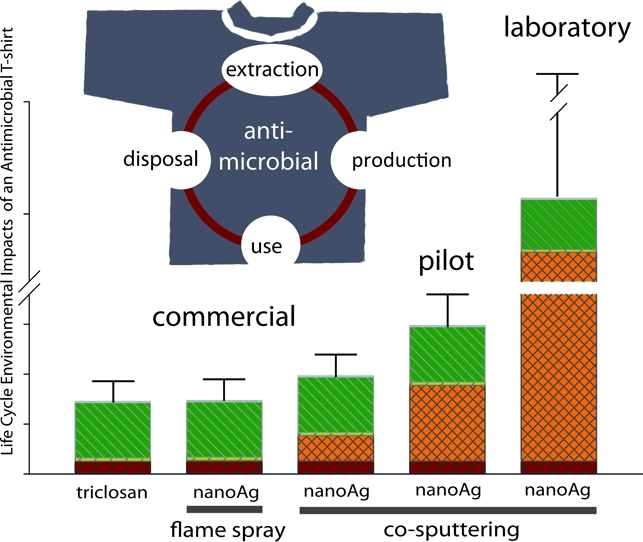

A cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment (LCA) is performed to compare nanosilver T-shirts with conventional T-shirts with and without biocidal treatment. For nanosilver production and textile incorporation, we investigate two processes: flame spray pyrolysis (FSP) and plasma polymerization with silver co-sputtering (PlaSpu). Prospective environmental impacts due to increased nanosilver T-shirt commercialization are estimated with six scenarios. Results show significant differences in environmental burdens between nanoparticle production technologies: The “cradle-to-gate” climate footprint of the production of a nanosilver T-shirt is 2.70 kg of CO2-equiv (FSP) and 7.67–166 kg of CO2-equiv (PlaSpu, varying maturity stages). Production of conventional T-shirts with and without the biocide triclosan has emissions of 2.55 kg of CO2-equiv (contribution from triclosan insignificant). Consumer behavior considerably affects the environmental impacts during the use phase. Lower washing frequencies can compensate for the increased climate footprint of FSP nanosilver T-shirt production. The toxic releases from washing and disposal in the life cycle of T-shirts appear to be of minor relevance. By contrast, the production phase may be rather significant due to toxic silver emissions at the mining site if high silver quantities are required.

Introduction

Nanotechnology is considered a major means of assisting environmental protection, avoiding increasing health care expenses, improving medical treatments, as well as coping with energy and resource limitations.1 However, emissions of nanoparticles may also be associated with environmental risks and adverse health effects. Therefore, it has been suggested that prospective environmental assessments should be performed to evaluate the potential merits and shortcomings of nanoproducts in an early stage of their development.2 In this study, we focus on nanosilver, which is widely applied worldwide, with the majority of applications in textiles.3 As compared to bulk silver, nanosilver has a higher antimicrobial efficacy because of (i) its large and highly reactive specific surface area and (ii) its higher dissolution rate.4 Even though potentially nanoscale colloidal silver has been widely applied in the last decades,5 the growing number of products containing engineered nanosilver calls for comprehensive as well as prospective environmental assessments.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) has been proposed to be a key to such comprehensive environmental assessments.2 LCA is an established tool for identifying environmental “hot spots” and for comparing products that provide the same services. However, there are little published inventory data of nanomaterials and nanoenabled products.6 Most studies focus on the production stage,7−11 while a few also include the use phase.12−14 None of these studies account for future developments in nanotechnology, although it is a quickly evolving technology. Moreover, except for the semiquantitative approach of Canis et al.,11 these studies do not include the nanospecific environmental effects of potentially released nanomaterials, but focus on energy and material use during their production.

The objective of this Article is to compare the environmental benefits and impacts of nanosilver T-shirts with conventional T-shirts and T-shirts treated with triclosan, a commonly applied biocide to prevent textiles from emitting undesirable odors.15 The environmental performance of two production technologies is investigated: (i) commercialized flame spray pyrolysis (FSP) with melt-spun incorporation of silver nanoparticles and (ii) plasma polymerization with silver cosputtering (hereafter abbreviated as PlaSpu) on the laboratory, pilot, and an estimated commercial scale. Second, the environmental impacts of conventional, nanosilver, and triclosan T-shirts are compared, with respect to the production, use, and disposal phase. Finally, we apply an adapted formative scenario analysis (FSA)16 to assess the environmental performance of nanosilver T-shirts considering both quantitative and qualitative future developments.

Method

Description of the Analyzed System and Life Cycle Inventory Analysis

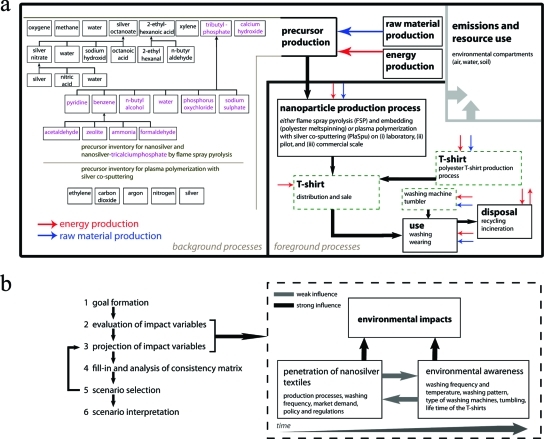

Figure 1a shows the system boundaries for the comparison of the life cycle of conventional T-shirts and T-shirts that are treated with nanoparticles or triclosan. The first nanoparticle production setting is based on the FSP technology17 with a current capacity of 500 kg/year (Nanograde GmbH Zurich). The FSP process was analyzed for pure nanosilver and for nanosized silver-tricalciumphosphate particles (nanoAg-TCP), both of which may be applied to textiles. A metal precursor (silver octanoate) is sprayed into a solvent-methane-oxygen flame. For nanoAg-TCP, precursors for tricalcium phosphate (TCP) are added to the process. The nanoparticles are then formed above the flame. Nanosilver settles on top of TCP and aggregates to nanoAg-TCP. The engineered nanoparticles are then collected from a filter. The nanoparticles in this case are introduced to fiber spinning via the addition of polymer masterbatch granules to the bulk fiber polymer during spinning in a hot-melt process followed by knit.18 The second production setting is the PlaSpu process19 on a laboratory and pilot scale at the Swiss Federal Laboratory for Materials Testing and Research (EMPA) in St. Gallen and on an estimated commercialized scale using expert opinion and conceptual drawings.20 The PlaSpu process uses a low-pressure plasma system to obtain a nanosilver coating. Nanoparticles are sputtered from a silver target and then embedded in a polymer matrix, which is applied to polyester fabric. Both nanosilver production settings including material conversion efficiencies, and yields are described in detail in the Supporting Information S1.

Figure 1.

(a) System boundaries; dashed boxes: activities not affected by nanotechnology and modeled equivalently in all analyses of this Article. (b) Adapted six-step procedure of the scenario construction.16

One T-shirt (1.56 m2 textile, 130 g) is assessed over all life cycle stages (Figure 1a). The commercialized antibacterial T-shirts were assumed to contain either 31 mg of pure nanosilver, 47 mg of nanoAg-TCP (0.93 mg of pure nanosilver), or 22 mg of triclosan (Supporting Information Table S20 and Figure S5). Also, higher biocidal concentrations were assessed: 3.7 g for triclosan T-shirts, and 2.6 g for nanosilver T-shirts, representing average values in the development stage of these products.

Background life cycle inventory (LCI) data were taken from the ecoinvent database (v2.2)21 whenever possible. If not available in ecoinvent, the LCI was established using data from technical handbooks, literature sources describing best available production technologies, or calculated with a chemical engineering approach (Supporting Information S1). New LCI unit processes were established for silver octanoate, tributylphosphate, n-butyraldehyde, and 2-ethylhexanoic acid (Supporting Information S1). The European UCTE mix was taken for electricity production. The energy use of triclosan production was estimated with the tool FineChem.22 Distillation processes for waste solvents were assessed with the Ecosolvent tool.23 Any remaining solvent mixture was assumed to be disposed by incineration, and the environmental impacts were calculated with the approach of Seyler et al.24

For the use phase, 100 washings were considered. LCI data for the use phase include water and energy use and emissions,25,26 washing powder,27 and material for washing and tumbling machines. The amount and form of silver released from PlaSpu T-shirts are reported in ref (28). Because of their similar size and shape, it is assumed that FSP T-shirts release silver to similar fractions in particulate and ionic form as PlaSpu T-shirts. Total release rates of 67% and 1.5% were estimated for silver and triclosan, respectively.28−30 The fate of silver and triclosan in the wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) was modeled with the software tool of Struijs et al.31 (Supporting Information Table S16/21). For the uncertain fate parameters, such as WWTP efficiency or bioavailability for instance, conservative removal rates were used. Disposal routes are assumed to be the same for all T-shirts (5% recycling, 95% incineration).32,33 While triclosan will be destroyed when the T-shirt is disposed of in an incineration plant, the behavior of nanoparticles during waste incineration is unknown.34 We assumed that 0.002% will be released into the air.35 Detailed LCI data are found in Supporting Information S4 and S9.

Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis

Sensitivities were assessed by varying single parameter values, such as biocidal concentrations, different precursor production technologies, and altering assumptions of consumer behavior, within realistic value ranges. Uncertainty analysis was carried out using the pedigree approach36 with a subsequent Monte Carlo Analysis (Supporting Information S8).

Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

LCIA results are shown for the analyzed products in terms of climate footprint (Global Warming Potential IPCC 2001, 100 yr, v1.0237) and sea- and freshwater toxicity38 (for additional LCIA results, such as nonrenewable cumulative energy demand; see Supporting Information Table S23). Characterization factors for waterborne emissions were calculated with USES-LCA38 (Supporting Information S9) and expressed as 1,4-dichlorobenzene-equivalents (1,4-DCB-equiv), according to the USES-LCA methodology. Only the dissolved fraction of silver releases from the wastewater treatment plant was considered as bioavailable and assessed in the LCIA (Supporting Information S9).

Scenario Construction

In a prospective LCA, we estimate the future environmental impacts using scenarios with the functional unit “being dressed with a biocidal polyester T-shirt for outdoor activities during one year in Switzerland (wearing it once a week)”. Variability in consumer habits due to different environmental awareness, technological changes, and market penetration of nanosilver textiles was considered.

The scenarios are developed and selected using a six-step procedure adapted from the formative scenario analysis (FSA),16 shown in Figure 1b. The time horizon of the scenarios is 2020, and the represented area is Switzerland (8.1 million inhabitants). The selection of impact variables and the assumed interactions between them are based on a conceptual framework including scenarios for nanotechnology developments in Switzerland.39 An impact variable is defined as a system element that influences the system behavior or is influenced by other system elements.40 Each variable in a specific scenario has up to three possible future states. Some of them are based on existing quantitative knowledge and estimations (e.g., penetration of nanoparticle production technologies, technical characteristics of washing machines, consumer behavior), while others are harder to describe quantitatively and therefore require a qualitative approach (e.g., patent data, policies, regulations). Out of the pool of consistent combinations of the impact variables’ future states,41 three scenarios that are internally driven by nanotechnology, and its market penetration were combined with three scenarios with externally driven variations in environmental awareness. Possible mutual interactions are explored in the Results section. The variety of the impact variables’ characteristics in these scenarios results in different environmental impacts due to different technological, social, and economic developments assumed and allows for exploring fields of improvement as well as critical context conditions. Specifics of the scenarios are shown in Table 1 and Supporting Information S11–14. For each “nano”-scenario, a baseline scenario “no nano” shows the difference from a future without nanosilver clothes.

Table 1. Scenario Characteristics and Description of the Impact Variables, Which Are Based on Different Technological Developments, Various Behavior Patterns, and Alternative Policy and Regulatory Constraintsa.

| Nanotechnology Development | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| impactvariables | scenario “slow development” | scenario “estimated development” | scenario “fast development” | scenario “no nano”b | explanations, assumptions |

| biocidal textiles | |||||

| nanoAg production and incorporation in textile | PlaSpu (commercial):FSP (20:80)c | FSP only | FSP only |

|

|

| nanosilver T-shirts per person (5 polyester T-shirts in total) | 0.5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| fraction of washing frequency of nanosilver T-shirts in comparison to conventional T-shirts | 1 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1 | |

| policy and regulation | no regulation in addition to the silver effluent threshold (0.1 mg/L) and airborne exposure limits (0.01 mg/m3) | •legal framework for the development and use of nanosilver in Switzerland, including laws, decrees, and self-regulations; only one state is considered because a ban of nanosilver would exclude all influence of nanotechnology on to the scenarios | |||

| Environmental Awareness | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| impact variables | scenario “low” | scenario “medium” | scenario “high” | ||

| water use per washing cycle | 63 L | 49 L | 35 L | •increased future demand for cleaner technologies drives the competition between producers of washing and tumbling machines (e.g., Xeros (42));e consumers with higher environmental awareness will prefer new washing machines with lower electricity and water demand; raw material requirements for washing machines and tumblers remain constant; depending on the environmental awareness, the tumbler is used differently: frequency of use changes and the clothes are either completely or nearly dried; lower environmental awareness results in lower washing loads and decreased lifespan of T-shirts (e.g., replacement assumed to be fashion driven) and higher washing temperatures | |

| electricity use per washing cycled | 0.76 kWh | 0.66 kWh | 0.57 kWh | ||

| electricity use per tumbling cycle | 2.22 kWh | 1.68 kWh | 1.68 kWh | ||

| number of washings (lifetime of T-shirt) | 20 | 50 | 100 | ||

| amount of T-shirts per washing load | 10 | 15 | 20 | ||

| tumbling frequency per T-shirt washing | same as washing frequency | one-half the washing frequency | one-tenth the washing frequency | ||

For details, see Supporting Information S11–14.

The assumption is that consumers are not aware of the applied triclosan and hence do not change their behavior. Therefore, the impact variables have the same value for either no biocides or applied triclosan.

PlaSpu: Plasma polymerization with silver cosputtering. FSP: Flame spray pyrolysis with melt spinning (incorporation process). 80% of the nanosilver T-shirts are produced with FSP and 20% with commercialized PlaSpu technology.

Average electricity demand per washing cycle (Supporting Information Table S14).

References (25,43) and own survey of washing and tumbling machine producers (Supporting Information S3).

Results

Flame Spray Pyrolysis

The climate footprint of the production of 1 kg of nanoAg-TCP is 120 kg of CO2-equiv (0.95 confidence interval (CI): 97.6–142 kg) and for nanosilver 213 kg of CO2-equiv/kg (0.95 CI: 189–241 kg). The climate footprint is mainly driven by the production process itself and precursor production, mainly the solvents (2-ethylhexanoic acid and xylene) and oxygen. However, the incorporation process of nanosilver and nanoAg-TCP has a climate footprint 2 orders of magnitude higher than nanoparticle production because of additional polyester requirements and high electricity demand for the coating (Table 2). Transportation in the supply chain contributes less than 0.5% to the footprint (Supporting Information S5). Silver mining and beneficiation has a much higher specific climate footprint per kilogram in comparison to the other precursors, but due to the low amount required for use, the influence on the results is small. For having the same antimicrobial effect, less nanosilver is required if aggregated with tricalcium-phosphate when applied in the same way.44 However, the additional precursors for tricalcium-phosphate offset this reduction in terms of climate footprint.

Table 2. Main Contributors to the Climate Footprint from the Production of Nanosilver Coating for One T-Shirta.

| kg of CO2-equiv |

kg of CO2-equiv |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSP with incorporation into fibers (meltspinning) | nano Ag-TCP | nanosilver | PlaSpu at different maturity stages | laboratory | pilot | commercialized (expert opinion) |

| incorporation process | 1.47 × 10–1 | 1.47 × 10–1 | electricity, UCTE | 153 | 8.80 | 0.111 |

| electricity UCTE | 5.37 × 10–2 | 5.35 × 10–2 | silver | 4.67 | 6.05 | 5.03 |

| particle production process | 2.06 × 10–3 | 1.36 × 10–3 | coating process | 2.52 | 0.215 | 0 |

| 2-ethylhexanoic acid | 7.66 × 10–4 | 5.05 × 10–4 | argon | 2.16 | 0.008 | 2.43 × 10–7 |

| tributylphosphate | 7.51 × 10–4 | carbon dioxide | 1.35 | 0.132 | 1.40 × 10–6 | |

| oxygen, liquid | 6.42 × 10–4 | 4.23 × 10–4 | ethylene | 0.38 | 0.024 | 7.62 × 10–7 |

| xylene | 4.83 × 10–4 | 3.19 × 10–4 | transport | 0.21 | 0.004 | 2.00 × 10–7 |

| silver octanoate | 1.06 × 10–4 | 3.49 × 10–3 | ||||

| total climate footprint | 0.21 | 0.20 | 164.0 | 15.24 | 5.14 | |

PlaSpu coating, 50 nm thick; nanosilver, 0.031 g; FSP coating, 5 μm thick; nanosilver, 0.031 g; nanoAg-TCP, 0.047 g.

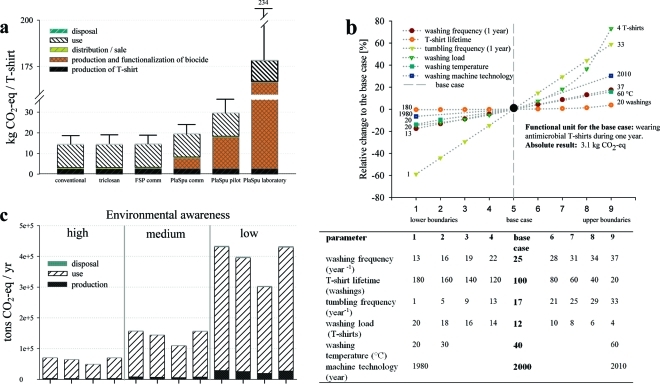

Plasma Polymerization with Silver Co-sputtering

The climate footprint of the PlaSpu process decreases with technological development (Figure 2a), although silver requirements increase when upscaling from lab scale due to the new production design. Electricity use is reduced from 288 kWh/T-shirt (laboratory scale) to 17 kWh/T-shirt (pilot scale) and is projected to improve to 0.21 kWh/T-shirt (commercial scale).20

Figure 2.

(a) Cradle-to-grave climate footprint of biocidal T-shirts and a regular T-shirt (100 washings). Error bars show the upper bound of the 95% confidence interval for the results (Monte Carlo analysis of the inventory, see also Supporting Information S8; Commercialized = Comm.). (b) Sensitivity analysis of the use phase. The parameter values are listed below the graphic. (c) Annual climate footprint (GWP IPCC 2001, 100 yr) of the scenarios with nanotechnology development on the bottom x-axis and changing environmental awareness on the top x-axis.

Product Comparison

FSP and triclosan T-shirts are produced with a much smaller climate footprint than are PlaSpu T-shirts. Distribution/sale and the disposal phase are of minor importance in the life cycle of the T-shirt and could be further lowered by reducing transport distances, avoiding air transport, and increasing energy efficiency in retail outlets. The use phase pollutes the environment most if commercial technologies are used (Figure 2a). On the contrary, nanosilver T-shirts produced with the noncommercialized PlaSpu technology have higher climate change impacts during production than in use. Greenhouse gas emissions show high sensitivities to washing load and frequency and lower sensitivities to T-shirt lifetime and washing temperature (Figure 2b). Of all tested parameters, a reduction or abandonment of tumbling would reduce the climate footprint the most.

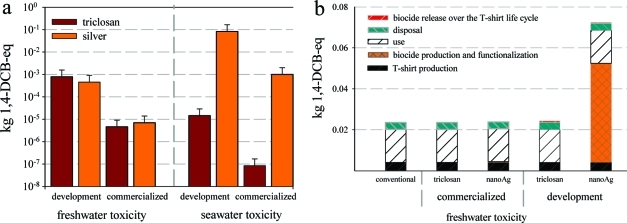

Toxic Impacts of Nanosilver and Triclosan T-Shirts

Elimination rates in wastewater treatment plants (WWTP) were modeled to be 91% w/w and 12% w/w for silver and triclosan, respectively, the former being slightly lower than literature values of 95% w/w.34,45 Silver in the effluent is either dissolved (29% w/w) or associated (71% w/w),31 forming strong complexes with ligands in water and consequentially losing its aquatic toxicity.46 Despite the differences in release amounts and elimination rates, the resulting toxic impact on freshwater is similar for silver and triclosan (Figure 3a, further LCIA results in Supporting Information S9 and S10). In contrast to freshwater toxicity, the seawater toxicity impact for the nondegradable silver is rather large in comparison to the slowly degradable triclosan (Figure 3a). The better fixation of triclosan in the textiles compared to nanosilver leads to a higher share of triclosan ending up in waste incineration plants, where it is expected to be destroyed completely. Both silver and triclosan emissions are not relevant when the whole life cycle of the conventional T-shirt is assessed (Figure 3b). While the silver released from washing contributes less than 1% to the overall freshwater toxicity of the nanosilver T-shirts, the production phase shows high sensitivities to the applied silver mass. The reason is that sulfidic tailings from silver mining may release long-term toxic emissions to the aquatic compartment.47

Figure 3.

(a) Freshwater and seawater toxicity of the released silver and triclosan during use and disposal phase; error bars show the upper end of the 95% confidence interval, representing the applied concentrations (Supporting Information Table S20 and Figure S5). (b) Freshwater toxicity for the life cycle of one T-shirt, distinguished between concentrations applied to commercialized (comm) and products in the development stage (dev). Nanosilver in the T-shirts is produced with FSP.

Scenario Analysis

Environmental awareness influences the climate footprint more than the market penetration of nanosilver clothes. While the climate footprint ranges for the “low environmental awareness” scenarios between approximately 300 and 435 ktons, it is between 50 and 70 ktons in the “high environmental awareness” cases (see also Supporting Information Tables S24 and S25). Within all awareness categories, the annual climate footprint for T-shirt use in Switzerland is lower in the nano than in the non-nano scenarios (including triclosan treated polyester T-shirts) because the additional burden of the nanosilver T-shirt production process is compensated with lower washing frequency (Figure 2c, Table 1). However, this is only the case for the FSP technology. Additional analyses indicate that a nanosilver T-shirt produced with commercial PlaSpu process will never perform better than regular T-shirts in terms of climate footprint, even if consumers decrease the impact of the use phase by reducing washing temperature, or washing and tumbling less.

Discussion

LCA of Nanoenabled T-Shirts

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to prospectively compare a nanoenabled product with a conventional biocide-containing product and a nontreated control product considering the complete life cycle. The selected technology for functionalization of textiles with FSP derived nanoparticles is environmentally and economically more efficient than with PlaSpu. However, specific advantages such as nanoscale polymeric layers with fine-tunable nanoparticle concentrations, currently not possible to produce with FSP and meltspinning, may lead to a successful market penetration of the PlaSpu technology in other markets, for example, for burn dressings in the biomedical sector.48 Moreover, reuse of the remaining silver plate in other industrial applications would allocate up to 39% of the impacts from the PlaSpu process to other processes. Size reduction of the silver plate and optimization of carbon dioxide input would lower the climate footprint further.

Considering the complete life cycle of T-shirts, the use phase is most important in terms of climate footprint when FSP-nanosilver or triclosan applications are assessed. Improvement potentials therefore lie in increased energy efficiency of washing and drying technology and change in consumer behavior, in particular regarding loads and frequency. Only some of these changes might be influenced by an enhanced market penetration of nanosilver textiles.

Impact Assessment Methodology

While the climate footprint assessment is based on a well-established method, the assessment of toxic impacts of nanosilver in the environmental compartments is at an early research stage.49,50 Hence, potential nanospecific effects are typically not taken into account in LCA studies so far. Regarding nanosilver emissions to water, environmental concentrations depend on the applied concentration during the polymer matrix fixation and on use and disposal of the nanosilver polyester T-shirts. There was not enough data for a distinction of silver release rates between different nanosilver coatings. Furthermore, the aquatic toxicity of metals shows large uncertainties because the bioavailability of the dissolved and colloidally bound phases of metals is not distinguished by current LCIA methods.51,52 The bioavailable fraction of silver is influenced by water chemistry,53 and it is most likely rather low in natural waters due to the formation of sulfide complexes.54 As in our study silver bioavailability was only considered for the WWTP effluent, but not with regard to the environmental fate further downstream, our estimation of the aquatic toxicity potential is probably overestimated. Thus, the results of the present study, which suggest that the aquatic toxicity potential of the directly released silver is relatively low in comparison to the aquatic toxicity over the entire life cycle of nanosilver T-shirts, are rather robust. On the other hand, the LCA results do not negate the need for further risk assessments, where absolute impacts are considered. Another point for future considerations is the assessment of degradation products, which are typically not assessed within LCA. Concerning triclosan for instance, the more bioaccumulative metabolite methyl-triclosan was not assessed.55

Further work is also needed for standardization of airborne exposure, especially at workplaces.56 Exposure to nanoparticles via inhalation could occur during FSP production50 but most likely not during the particle-textile incorporation process, which takes place in a closed system.57 Exposure during PlaSpu is unlikely as nanoparticles are produced and incorporated in a vacuum. Data on workplace exposure and chronic inhalation toxicity of silver nanoparticles including potential nanospecific effects are rather scarce (e.g., ref (58)) and should be investigated further.

To further develop the LCA methodology for nanomaterials, they should be characterized using the main properties that determine their toxicity. For some substances, increased toxicity has been demonstrated for the nanoparticle form,59 which should be considered in LCA studies. On the other hand, the primary particle size distribution mode of emitted engineered nanomaterials may shift into the micro range due to agglomeration and aggregation, and therefore nanomaterials may lose their nanospecific toxic effects60−62 if deagglomeration can be excluded. Hence, appropriate metrics for inventory and impact assessment need to be defined, for example, surface area, number concentration, and/or others. This would improve the linkage between exposure and effects and would facilitate carrying out LCAs of nanomaterials.

Scenario Outcomes

Although the scenarios only provide a snapshot of possible future technological developments and variability of environmental awareness, their spectrum gives a reasonable insight to the range of potential environmental impacts. It was shown that the general environmental awareness of the public, concerning washing behavior, influences the environmental impact of the T-shirt more than assumptions about the future development and acceptance of nanosilver T-shirts. More efficient washing technologies, using tumblers less, and lowering the washing temperature with special detergents would allow environmental impacts to be reduced significantly. Increasing environmental awareness might also result in a higher recycling rate of textiles and less turnover because of longer-term trends in fashion. In addition to this, the use of nanosilver T-shirts can decrease the climate footprint as compared to conventional clothing. However, the added climate change impact during production is turned into a net climate benefit over a T-shirts’ lifetime only if there is an increased awareness of nanosilver’s biocidal functionality, which was assumed to be the case in the scenarios assessed. Whether such changes in washing behavior are a realistic assumption remains an open question. Chemical treatment could lead to reduced washing, which was not considered here, because we assumed that manufacturers do not advertise treatment of textiles with, for example, triclosan due to potential consumer concerns. Nevertheless, any applied biocide to T-shirts will increase their ecotoxicity, which should be critically compared to changes in other impact categories such as the climate footprint.

Even though the “nano-scenarios” are modeled as independent from the “environmental awareness scenarios”, there might be a link between them. A high market penetration of nanosilver clothes enhances the perception of their benefits, which may lead to an overall reduction of washing frequency and temperature and lowers the total climate footprint.

Added Value of LCA in Combination with Scenario Analysis

This study is one of the first that analyzes material and energy inputs and environmental impacts such as climate footprint and toxicity over the whole life cycle of a nanoenabled product in combination with future scenarios. It is suggested that nanoenabled products should be compared to existing products before commercialization to avoid additional environmental burdens. The scenarios support the finding that in the use phase a higher environmental awareness substantially lowers the CO2-equiv emissions. The insights gained can help policy makers to better consider the future development of the production and use of nanosilver textiles, and industry to optimize processes and products.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Enrico Koerner (EMPA St.Gallen, Switzerland), Norman Luechinger (Nanograde GmbH Zurich, Switzerland), and Murray Height (HeiQ, Bad Zurzach) for data provision and feedback. Funding from “Prosuite”, a research project under the Seventh Framework Program of the European Commission (Reference number 227078), is gratefully acknowledged.

Supporting Information Available

Detailed descriptions of methods applied, calculation procedures, and more results. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplementary Material

References

- Schmid G.; Brune H.; Grunwald A.; Krug H.. Nanotechnology - Assessment and Perspectives; Springer: Heidelberg, 2006; Vol. 27, p 494. [Google Scholar]

- Klöpffer W.; Curran M. A.; Frankl P.; Heijungs R.; Köhler A.; Olsen S. I.. Nanotechnology and Life Cycle Assessment - A Systems Approach to Nanotechnology and the Environment; Washington, DC, 2007; p 30. [Google Scholar]

- Woodrow Wilson International Centre For Scholars, The Nanotechnology Consumer Inventory. Washington, DC, 2009.

- Sotiriou G. A.; Pratsinis S. E.. Antibacterial activity of nanosilver ions and particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5649−5654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack B.; Krug H. F.; Height M. 120 years of nanosilver history: Implications for policy makers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 1177–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D. E.; Curran M. A.; Gonzalez M. A. An examination of existing data for the industrial manufacture and use of nanocomponents and their role in the life cycle impact of nanoproducts. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 1256–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterwalder N.; Capello C.; Hungerbühler K.; Stark W. J. Energy consumption during nanoparticle production: How economic is dry synthesis?. J. Nanopart. Res. 2006, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir D.; Sandén B. Energy requirements of carbon nanoparticle production. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 12, 360–375. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan N.; Boyd S.; Somani A.; Raoux S.; Clark D.; Dornfeld D. A hybrid life cycle inventory of nano-scale semiconductor manufacturing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 3069–3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna V.; Bakshi B. R. Carbon nanofiber polymer composites: Evaluation of life cycle energy use. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2078–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canis L.; Linkov I.; Seager T. P. Application of stochastic multiattribute analysis to assessment of single walled carbon nanotube synthesis processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8704–8711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roes A. L.; Marsili E.; Nieuwlaar E.; Patel M. K. Environmental and cost assessment of a polypropylene nanocomposite. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 212–226. [Google Scholar]

- Reijnders L. Design issues for improved environmental performance of dye-sensitized and organic nanoparticulate solar cells. J. Cleaner Prod. 2010, 18, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd S. M.; Lave L. B. Life cycle economic and environmental implications of using nanocomposites in automobiles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 3458–3466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan M.; Kut D.; Gunesoglu C. Use of triclosan as antibacterial agent in textiles. Indian J. Fibre Text. Res. 2007, 32, 114–118. [Google Scholar]

- Scholz R. W.; Tietje O.. Embedded Case Study Methods. Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge; Thousand Oaks, Sage: London, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kammler H. K.; Mädler L.; Pratsinis S. E. Flame synthesis of nanoparticles. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2001, 24, 583–596. [Google Scholar]

- Giessmann A.Substrat- und Textilbeschichtung, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2002; p 180. [Google Scholar]

- Hegemann D.; Amberg M.; Ritter A.; Heuberger M. Recent developments in Ag metallised textiles using plasma sputtering. Mater. Technol. 2009, 24, 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- Körner E.; Hegemann D. Personal Communication, St. Gallen, 2008.

- Frischknecht R.; Doka G.; Dones R.; Heck T.; Hellweg S.; Hischier R.; Nemecek T.; Rebitzer G.; Spielmann M.; Wernet G.. Overview and Methodology. Final report ecoinvent v2.0 No. 1, 2007; p 77.

- Wernet G.; Papadokonstantakis S.; Hellweg S.; Hungerbühler K. Bridging data gaps in environmental assessments: Modeling impacts of fine and basic chemical production. Green Chem. 2009, 11, 1826. [Google Scholar]

- Capello C.; Hellweg S.; Badertscher B.; Betschart H.; Hungerbühler K. Environmental assessment of waste-solvent treatment options. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Seyler C.; Hofstetter T.; Hungerbuhler K. Life cycle inventory for thermal treatment of waste solvent from chemical industry: a multi-input allocation model. J. Cleaner Prod. 2005, 13, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Rüdenauer I.; Eberle U.; Griesshammer R.. Ökobilanz und Lebenszykluskostenrechnung Wäschewaschen; Oeko-Institut e.V.: Freiburg, 2006; p 147. [Google Scholar]

- Saouter E.; van Hoof G.; Feijtel T. C. J.; Owens J. W. The effect of compact formulations on the environmental profile of northern European granular laundry detergents - Part II: Life cycle assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2002, 7, 27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler A.; Wildbolz C. Comparing the environmental footprints of home-care and personal-hygiene products: the relevance of different life-cycle phases. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8643–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geranio L.; Heuberger M.; Nowack B. The behavior of silver nanotextiles during washing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 8113–8118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R.; Münstedt H. Silver ion release from antimicrobial polyamide/silver composites. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2081–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regional Authority for Consumer Protection and Food Control Lower Saxony (Niedersaechsisches Landesamt für Verbraucherschutz). Triclosan and Silver in Textiles - Reply on Information Request, 2010.

- Struijs J.SimpleTreat 3.0: a model to predict the distribution and elimination of chemicals by sewage plants; National Institute of Public Health and the Environment: The Netherlands, Bilthoven (Netherlands), 1996; p 49. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Statistik, Zukuenftige Bevoelkerungsentwicklung - Daten, Indikatoren - Kantonale Szenarien - Wohnverhaeltnisse; BfS: Neuenburg, 2008; Vol. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Textiles Industry. Entsorgung/Recycling; TVS Textilverband der Schweiz: Zurich, 2007; p 32. [Google Scholar]

- Mueller N. C.; Nowack B. Exposure modeling of engineered nanoparticles in the environment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 4447–4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk F.; Sonderer T.; Scholz R. W.; Nowack B. Possibilities and limitations of modeling environmental exposure to engineered nanomaterials by probabilistic material flow analysis. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2010, 29, 1036–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidema B.; Wesnas M. Data quality management for life cycle inventories - an example of using data quality indicators. J. Cleaner Prod. 1996, 4, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Houghton J.; Ding Y.; Griggs D.; Noguer M.; van Der Linden P.; Xiaosu D.. Climate Change: The Scientific Basis; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland,2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huijbregts M.; Thissen U.; Guinée J. B.; Jager T.; Kalf D.; van De Meent D.; Ragas A. M. J.; Wegener Sleeswijk A.; Reijnders L. Priority assessment of toxic substances in life cycle assessment. Part I: Calculation of toxicity potentials for 181 substances with the nested multi-media fate, exposure and effects model USES-LCA. Chemosphere 2000, 41, 541–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiek A.; Gasser L.; Siegrist M. Systemic scenarios of nanotechnology: Sustainable governance of emerging technologies. Futures 2009, 41, 284–300. [Google Scholar]

- Spoerri A.; Lang D. J.; Binder C. R.; Scholz R. W. Expert-based scenarios for strategic waste and resource management planning–C&D waste recycling in the Canton of Zurich, Switzerland. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 2009, 53, 592–600. [Google Scholar]

- Tietje O. Identification of a small reliable and efficient set of consistent scenarios. Eur. J. Operational Res. 2005, 162, 418–432. [Google Scholar]

- The Economist - Technology Quarterly, Washing without water: nylon beads in washing machines. The Economist Group: New York; Economist, 2009; Vol. 392. [Google Scholar]

- Gujer W.Siedlungswasserwirtschaft; Springer: New York, 2002; p 461. [Google Scholar]

- Loher S.; Schneider O. D.; Maienfisch T.; Bokorny S.; Stark W. J. Micro-organism-triggered release of silver nanoparticles from biodegradable oxide carriers allows preparation of self-sterilizing polymer surfaces. Small 2008, 4, 824–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt M.; Zuleeg S.; Kägi R.; Sinnet B.; Eugster J.; Boller M.; Siegrist H. Verhalten von nanosilber in kläranlagen und dessen einfluss auf die nitrifikationsleistung in belebtschlamm. Umweltwiss. Schadst.-Forschung 2010, 22, 529–540. [Google Scholar]

- Bielmyer G. K.; Grosell M.; Paquin P. R.; Mathews R.; Wu K. B.; Santore R. C.; Brix K. V. Validation study of the acute biotic ligand model for silver. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2007, 26, 2241–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classen M.; Althaus H.-J.; Blaser S. A.; Tuchschmid M.; Jungbluth N.; Doka G.; Faist Emmenegger M.; Scharnhorst W.. Life Cycle Inventories of Metals. Final Report ecoinvent data v2.1, No 10; Swiss Centre for Life Cycle Inventories: Duebendorf, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilev K.; Sah V.; Anselme K.; Ndi C.; Mateescu M.; Dollmann B.; Martinek P.; Ys H.; Ploux L.; Griesser H. J. Tunable antibacterial coatings that support mammalian cell growth. Nano Lett. 2010, 10, 202–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijnhoven S.; Peijnenburg W.; Herberts C.; Hagens W.; Oomen A.; Heugens E.; Roszek B.; Bisschops J.; Gosens I.; Van De Meent D.; Dekkers S.; De Jong W.; van Zijverden M.; Sips A.; Geertsma R. Nano-silver - a review of available data and knowledge gaps in human and environmental risk assessment. Nanotoxicology 2009, 3, 109–138. [Google Scholar]

- Demou E.; Stark W. J.; Hellweg S. Particle emission and exposure during nanoparticle synthesis in research laboratories. Ann. Occup. Hyg. 2009, 53, 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi N.; Diamond M. L.; van de Meent D.; Huijbregts M. A. J.; Peijnenburg W. J. G. M.; Guinée J. New method for calculating comparative toxicity potential of cationic metals in freshwater: Application to copper, nickel, and zinc. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 5195–5201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond M. L.; Gandhi N.; Adams W. J.; Atherton J.; Bhavsar S. P.; Bulle C.; Campbell P. G. C.; Dubreuil A.; Fairbrother A.; Farley K.; Green A.; Guinee J.; Hauschild M. Z.; Huijbregts M. a. J.; Humbert S.; Jensen K. S.; Jolliet O.; Margni M.; McGeer J. C.; Peijnenburg W. J. G. M.; Rosenbaum R.; Meent D.; Vijver M. G. The clearwater consensus: the estimation of metal hazard in fresh water. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 143–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jin X.; Li M.; Wang J.; Marambio-Jones C.; Peng F.; Huang X.; Damoiseaux R.; Hoek E. M. V. High-throughput screening of silver nanoparticle stability and bacterial inactivation in aquatic media: Influence of specific ions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7321–7328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowack B. Nanosilver revisited downstream. Science 2010, 330, 1054–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escher B. I.; Fenner K.. Recent advances in environmental risk assessment of transformation products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Brouwer D. Exposure to manufactured nanoparticles in different workplaces. Toxicology 2010, 269, 120–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechter M.Applications of suspended Nano Silver - A Case Study, 3rd Nano Safety for Success Dialogue; Brussels, 2009; p 28.

- Sung J. H.; Ji J. H.; Yoon J. U.; Kim D. S.; Song M. Y.; Jeong J.; Han B. S.; Han J. H.; Chung Y. H.; Kim J.; Kim T. S.; Chang H. K.; Lee E. J.; Lee J. H.; Yu I. J. Lung function changes in Sprague-Dawley rats after prolonged inhalation exposure to silver nanoparticles. Inhalation Toxicol. 2008, 20, 567–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffin R.; Tran L.; Brown D.; Stone V.; Donaldson K. Proinflammogenic effects of low-toxicity and metal nanoparticles in vivo and in vitro: Highlighting the role of particle surface area and surface reactivity. Inhalation Toxicol. 2007, 19, 849–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbach L. K.; Grass R. N.; Stark W. J. Physico-chemical differences between particle- and molecule-derived toxicity: Can we make inherently safe nanoparticles?. Chimia 2009, 63, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen K.; Alenius H.; Norppa H.; Pylkkänen L.; Tuomi T.; Kasper G. Risk assessment of engineered nanomaterials and nanotechnologies – A review. Toxicology 2010, 269, 92–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers K. W.; Palazuelos M.; Moudgil B. M.; Roberts S. M. Characterization of the size, shape, and state of dispersion of nanoparticles for toxicological studies. Nanotoxicology 2007, 1, 42–51. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.