Abstract

Introduction

Exercise may improve cancer outcomes. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NC) for breast cancer provides a unique setting to evaluate intervention effects. Treatments leading to decreased post-neoadjuvant Ki-67 levels, smaller tumor size, and higher pathologic response are associated with improved survival and lower recurrence. This randomized, prospective pilot trial evaluates the feasibility of supervised exercise during NC for breast cancer.

Methods

Stage II-III, ER positive, cancer patients with BMI > 25 receiving NC were randomized to standard NC with supervised bootcamp (NC + BC) or NC alone. Ki-67, C-peptide, BMI, and tumor size were measured before chemotherapy and at time of surgery.

Results

There were no initial differences between groups in regards to tumor size, C-peptide, BMI, and Ki–67. The NC + BC (n = 5) group had a lower mean BMI at the conclusion of NC compared with those (n = 5) in the NC group (28.0 versus 35.8, P = 0.03). Final tumor size was 2.59 cm in the NC + BC group versus 3.16 cm for NC (P = 0.76) Mean Ki-67 for NC + BC was 7% versus 29% with NC (P = 0.14). C-peptide (ng/mL) was equivalent between the two groups (4.55 NC + BC versus 4.74 NC, P = 0.85).

Conclusions

Adding a supervised exercise program to NC is feasible, decreases BMI, and may lead to lower Ki-67 levels and improved survival.

Keywords: breast cancer, exercise, Ki-67, neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Introduction

A growing body of evidence suggests that cancer patients may benefit from physical activity.1–7 The majority of previous studies have focused on impact upon quality of life6–8 amongst survivors. Research reveals improvements in cardio-respiratory fitness, physical functioning, and decreased fatigue in cancer patients who receive exercise interventions.8 There is some evidence, however, that there may also be decreased rates of breast cancer specific mortality in survivors who engage in increased physical activity.1,3

Although most studies evaluating physical activity and breast cancer indicate a favorable impact,3–5 the generally excellent prognosis from multi-modality treatment of breast cancer in the United States9 makes it difficult to isolate the effect of the exercise itself. The majority of research on breast cancer and physical activity evaluates exercise in the post-treatment setting,3,5,10–14 even though the ability to impact lifestyle changes may be at the time of initial diagnosis.15

This study was therefore designed to evaluate the feasibility and impact of a supervised exercise regimen given during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer, a time when patients may be more receptive to lifestyle changes. For patients with locally advanced breast cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy is the initial treatment of choice.16 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy allows for an immediate assessment of response and can provide valuable information regarding prognosis and therapeutic efficacy.17,18

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first randomized pilot trial to take advantage of the well-known prognostic value of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in order to evaluate the efficacy, as defined by known prognostic biomarker changes, of a supervised bootcamp exercise intervention in patients with locally advanced breast cancer.

Methods

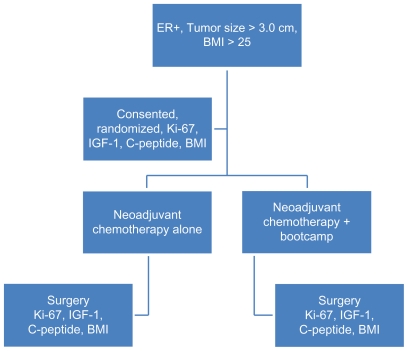

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, all patients were diagnosed and treated between March, 2009 and April, 2011. Women undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for locally advanced, non-metastatic breast cancer were randomized to the bootcamp arm (an exercise protocol supervised by an experienced personal trainer) or chemotherapy alone. Randomization was performed by reviewing the study protocol with eligible patients. Once they had been consented for the study, an unlabeled envelope was opened by the research coordinator to place the patient in either the control or bootcamp arm of the study. To be eligible for the protocol, patients had to have estrogen receptor positive breast cancer and have a body mass index (BMI) greater than 25. Insulin dependent diabetic patients were excluded. This design allowed for a uniform group of patients who were unlikely to have previously exercised, and who had similar tumor features and consequently would have been expected to have equivalent responses to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Approximately 500 breast cancer patients are treated annually at the cancer center, review of tumor registry data estimated 80 patients would meet all inclusion/exclusion criteria for this study every year. 10 patients ultimately met all criteria and agreed to participate. All eligible patients were approached by study coordinators to discuss study participation. Patients received standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy at the discretion of the medical oncologist, per institutional protocols, with the standard institutional regimen being dose dense adriamycin, cyclophosphamide and taxol (AC + T). Exercise for the bootcamp arm was started within one week of the first chemotherapy cycle. Specific endpoints evaluated both before and after chemotherapy were Ki-67 in the tumor, tumor size, axillary lymph node status, insulin growth factor 1(IGF-1) levels, C-peptide levels, and BMI. Clinical and pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy at the breast and axillary site were also recorded (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Study design.

Note: Schema of randomized pilot trial.

Abbreviations: ER, estrogen receptor; BMI, body mass index; IGF-1, IGF-insulin like growth factor 1.

Exercise intervention

The exercise regimen chosen involved a bootcamp program which included both aerobic training and resistance activities. Resistance activity is associated with improvements in lean body mass,19 which may impact insulin resistance, and this was therefore incorporated into the exercise program. Aerobic training is important for overall cardio-respiratory health, and was therefore also included in the bootcamp program. During the sessions, patients engaged in intervals of activities such as jumping jacks, running in place, arm and leg work with exercise balls, bands, and weights up to 5 pounds. Patients were pushed to their individual tolerance levels, a total of 48 sessions were prescribed. To optimize compliance, patients were allowed to choose whether they preferred a home based regimen where a personal trainer came to the patients house for 1 hour three times a week, or if they wished to participate in a group session, open to the public, that occurred 5 days a week, with the patients on trial only required to attend three times per week.

Biomarker rationale

Ki-67

Human Ki-67 is a protein associated with cell proliferation. It has significant value for predicting survival and recurrence risk in cancer patients.18,20,21 Post neoadjvuant chemotherapy Ki-67 of < 12% correlates with reduced rates of recurrence.22 In addition, greater decreases in Ki-67 in breast cancer patients correlate with improved disease-free survival, overall survival, and lower rates of recurrence.21–23 Ki-67 was measured in the initial core biopsy specimen and then again in the final resection specimen removed for definitive surgical intervention after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ki-67 was reported outside of the standard pathology report and interpreted by a single breast pathology fellowship trained pathologist who was not aware of which study arm the patient was in.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) assay and image quantitation methods for Ki-67

Quantitative IHC was used to determine Ki-67 expression in the breast tumors. IHC staining was performed using a TechMate 1000 automated immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Arizona). A known positive control section was included in each run to assure proper staining. Rabbit immunoglobulin fraction (Normal) or non-specific IgG1 monoclonal diluted with PBS was used as a negative control. A monoclonal antibody was used for Ki-67 (MIB-1, predilute, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Arizona).

Quantitative information for staining was obtained using the automated microscopy method, Ventana Imaging Analysis System (VIAS, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, Arizona). The microscope module scanned the immunohistochemically stained slides, and the computer monitor displayed the digitalized tissue images. After viewing the high-magnification images on the VIAS computer, several subregions of the digitalized tissue images were selected for analysis by the VIAS. Positivity of Ki-67 was determined by the presence of nuclear staining. Grading was based on the percentage of stained tumor cells.

IGF-1and C-petide

There appears to be a link between insulin resistance (IR) and breast cancer.24–28 Additionally, patients in exercise programs demonstrate decreased IR.26,29 Decreased resistance to insulin may, in part, account for improved outcomes in breast cancer survivors who engage in physical activity.1 Fasting serum C-peptide levels were monitored as an indicator of insulin resistance as was IGF-1, which have been shown to be influenced by exercise.30 Decreasing insulin resistance may provide this survival benefit by decreasing cancer cell proliferation.

Student’s t-test was performed to examine the difference of each outcome measure between the control group and the bootcamp group. The comparison was performed before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, respectively. The changes of the outcome before and after treatment were also compared between these two groups by t test. All reported P-values are two-sided and the statistical analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Ten patients were randomized and completed all study parameters and were included in this analysis. All five patients in the bootcamp group completed > 80% of the advised exercise sessions, all patients in the control arm received chemotherapy and underwent the required blood draws. Mean age for all patients at the time of diagnosis was 55 years, and mean tumor size was 4.97 cm (Table 1). The majority of patients found their tumors on breast self exam, and most patients had an invasive ductal carcinoma on pathology (Table 1). Five patients (3 controls and 2 study) did not meet standard indications for genetic testing, and it was therefore not offered. Four patients (1 control, 3 study) were tested and found to be negative for BRCA1/2 mutations, 1 patient in the control group was diagnosed as a BRCA2 mutation carrier. Nine patients received AC + T, one patient in the control arm received taxotere, carboplatin and trastuzumab. All neoadjuvant chemotherapy was completed in 4–6 months after diagnosis, bootcamp was given during this entire time. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in regards to tumor size, age, BMI, tumor grade, C- peptide levels, or initial Ki-67 (Table 1). All patients had axillary nodal metastases and subsequently underwent completion axillary lymph node dissection (ALND). Seven patients were diagnosed with the axillary metastases via ultrasound guided percutaneous needle biopsy prior to starting neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 6 patients underwent core needle biopsy, and 1 underwent fine needle aspiration. The additional 3 patients had initial clinically and sonographically negative axillas, and therefore underwent sentinel node biopsy at the completion of neoadjvuant chemotherapy. All 3 were found to have axillary nodal metastases and underwent ALND (Table 1).

Table 1.

Initial characteristics.

| Control | Bootcamp | All | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 51.4 | 59.8 | 55.6 | 0.21 |

| Tumor type | ||||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 4 | 4 | 8 | 1.00 |

| Invasive lobular carcinoma | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Initial tumor size (mean) cm | 4.88 | 5.06 | 4.97 | 0.91 |

| Method of tumor detection | ||||

| Breast self exam | 4 | 5 | 9 | 1.00 |

| Mammogram | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pre-op BMI (mean) | 36.59 | 30.57 | 33.58 | 0.13 |

| Initial Ki-67% (mean) | 42 | 34 | 38 | 0.56 |

| Grade | ||||

| II | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.52 |

| III | 4 | 2 | 6 | |

| Axillary metastases diagnosis | 1.00 | |||

| Percutaneous biopsy | 3 | 4 | 7 | |

| Sentinel node | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Initial C-peptide (mean) ng/mL | 6.57 | 5.80 | 6.18 | 0.81 |

| Initial IGF-1 (mean) ng/mL | 187.7 (n = 3) | 130.7 (n = 3) | 159.2 | 0.052 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IGF, insulin like growth factor 1.

At the time of surgical intervention, along with their ALND, 6 patients underwent total mastectomy, and 4 underwent partial mastectomy. There were a median of 8.6 positive nodes at ALND (range = 1–16) in the bootcamp group versus 2.4 positive nodes (range = 0–8) in the control group. Final pathologic tumor size was equivalent between the two groups (Table 2). Residual cancer burden (RCB)31 was Class III in three patients (2 in the bootcamp group and 1 in the control), Class II in six patients (3 bootcamp, 3 control) and Class I in one control patient.

Table 2.

Analysis after intervention.

| Control | Bootcamp | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-chemotherapy pathologic tumor size (mean) cm | 3.16 | 2.59 | 0.76 |

| Post-chemotherapy Ki-67% (mean) | 29 | 7 | 0.14 |

| Change in Ki-67% (mean ± SEM) | 27.2 ±7.6 | 13.2 ± 11.7 | 0.35 |

| Post-chemotherapy BMI (mean) | 35.8 | 28.0 | 0.03 |

| BMI change (mean ± SEM) | 0.79 ± 0.69 | 2.54 ± 1.47 | 0.32 |

| Post-chemotherapy C-peptide (mean) ng/mL | 4.74 | 4.55 | 0.85 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SEM, standard error of the mean.

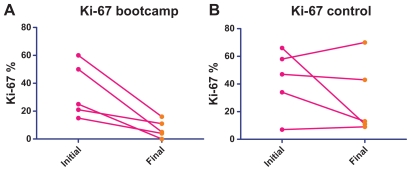

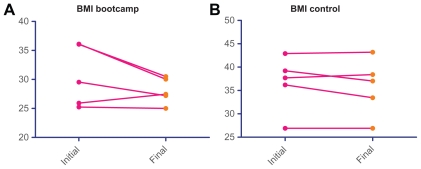

For bootcamp patients, mean Ki-67 level after neoadjuvant chemotherapy was 7.2% (7.2% ± 2.8%) versus 29.2% (29.2% ± 12.0%) in the control group (Table 2 and Fig. 2A and B). Fasting C-peptide levels decreased in both groups, and there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 2). BMI in the control group was 35.8 (35.8 ± 2.7), versus 28.0 (28.0 ± 1.0) in the bootcamp group after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, which was a statistically significant difference (P = 0.03, Table 2). BMI change and C-peptide change, when evaluated for each individual patient, was also greater in the bootcamp group (Figs. 2A and B and 3A and B), although this was not statistically significant (Table 2). Mean BMI change in the control group was 0.79 ± 0.69 versus 2.54 ± 1.47 in the bootcamp group (P = 0.32) Initial IGF-1 was collected for 3 patients in the bootcamp group, mean initial IGF-1 was 130.7 and increased to 160 at the conclusion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The control group had 3 patients with a mean initial IGF-1 of 187.7 and the follow-up IGF-1 was 171.0. The change in IGF-1 between the two groups was not statistically significant (P = 0.31). At a median follow-up of 21.6 months, there has been no local or systemic recurrence in either group. All patients continue to take adjuvant hormonal therapy. Multivariate analysis was attempted to ascertain factors predicting a Ki-67 of <12% after chemotherapy, no significant factors were identified, likely due to the small sample size in this pilot study.

Figure 2.

Ki-67 change.

Notes: Ki-67 initial reflects Ki-67 in core biopsy sample, final reflects Ki-67 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in final surgical specimen for each patient. Bootcamp arm had marked changes in Ki-67, a potential indicator of improved breast cancer prognosis.

Figure 3.

BMI change.

Notes: Patient BMI at the time of diagnosis and at the conclusion of neaodjuvant chemotherapy. Statistically significant changes (P=0.03) in BMI were noted in the bootcamp arm.

Discussion

This pilot study reveals the feasibility of an exercise intervention for patients undergoing neoadjvuant chemotherapy for breast cancer. The study is clearly limited by its small sample size, but does provide an innovative framework for incorporation of physical activity into a patient’s lifestyle.

C-peptide and BMI

The reductions in C-peptide levels in the exercise group were not as significant as expected. Irwin32 et al examined the association between C-peptide levels and breast cancer death amongst survivors. A C-peptide level greater than 2.5 ng/mL correlated with a two-fold increased risk of breast cancer death when compared to those women who’s C-peptides were <1.7 ng/mL (HR 2.39, 95% CI 1.00–7/50). One explanation for the lack of C-peptide reductions may be the patients’ BMI. There appears to be an association between BMI and C-peptide levels,33 and although BMI reductions were noted in the bootcamp group, these may not have been drastic enough to influence C-peptide levels to <1.7.

In the bootcamp arm, 4 of 5 patients continued to be overweight, as defined by a BMI of 25–30, at the conclusion of the study. One bootcamp patient was able to achieve a normal BMI of <25. In contrast, for patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, 4 of 5 patients were morbidly obese, as defined by a BMI of >35, and 1 patient was overweight at study conclusion.

IGF-1

Studies reveal an association between lower IGF-1 levels and signs or symptoms of cardiovascular disease.34 Therefore, the increases in IGF-1 levels demonstrated in the bootcamp arm are potentially reflective of improved cardiovascular fitness due to exercise, and may decrease mortality in this patient population.

Compliance

Overall compliance with bootcamp in this prospective pilot trial was excellent. Despite the well known benefits of exercise, compliance with increased physical activity regimens is poor.35 Barriers to exercise for cancer patients in particular include distance to travel for exercise, and a lack of recommendation by a physician.15 The home based exercise program utilized in this protocol overcomes both of these issues, subsequently compliance with this protocol was very high with all patients in the bootcamp group completing at least 80% of the advised exercise sessions. The current bootcamp protocol requires intensive one- on-one supervision, and while the utilization of resources up front are significant, the decreased BMI in the exercise group and adherence to the protocol may predict higher long-term commitment to increased physical activity and a true behavioral change for these patients.36 In addition, the weight gain normally seen with chemotherapy37,38 was not observed in the patients in the exercise arm, a factor which may also improve long term survival.

Future directions

The results from this pilot study are promising, and support the use of and feasibility of exercise regimens in the neoadjuvant setting. Exercise may be a potentially useful tool for impacting tumor biology, in addition to the known quality of life improvements. Future studies are planned to validate these results in a multi-institutional, prospective trial to provide adequate power and potentially statistical significance. Additionally, further studies to determine the minimum “dose” of exercise required to achieve lower Ki-67 levels are also needed.

Conclusion

This pilot study supports the feasibility and potential benefits from a focused exercise intervention given during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank the patients who participated in this trial, Dallas County Bootcamp, Commercial Real Estate Women’s group of Dallas, Linda Flores, and Madhu Rao.

Financial support received from a grant given by the Commercial Real Estate Women of Dallas, Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT0141178.

Footnotes

Disclosures

Author(s) have provided signed confirmations to the publisher of their compliance with all applicable legal and ethical obligations in respect to declaration of conflicts of interest, funding, authorship and contributorship, and compliance with ethical requirements in respect to treatment of human and animal test subjects. If this article contains identifiable human subject(s) author(s) were required to supply signed patient consent prior to publication. Author(s) have confirmed that the published article is unique and not under consideration nor published by any other publication and that they have consent to reproduce any copyrighted material. The peer reviewers declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ogunleye AA, Holmes MD. Physical activity and breast cancer survival. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:106. doi: 10.1186/bcr2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–34. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, Kroenke CH, Colditz GA. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA. 2005;293:2479–86. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones LW, Douglas PS, Eves ND, et al. Rationale and design of the Exercise Intensity Trial (EXCITE): a randomized trial comparing the effects of moderate versus moderate to high-intensity aerobic training in women with operable breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:531. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, et al. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2345–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abrahamson PE, Gammon MD, Lund MJ, et al. Recreational physical activity and survival among young women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2006;107:1777–85. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reigle BS, Wonders K. Breast cancer and the role of exercise in women. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:169–89. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-492-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, Klassen TP, Mackey JR, Courneya KS. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holick CN, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, et al. Physical activity and survival after diagnosis of invasive breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:379–86. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irwin ML, Smith AW, McTiernan A, et al. Influence of pre- and postdiagnosis physical activity on mortality in breast cancer survivors: the health, eating, activity, and lifestyle study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3958–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.9822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.West-Wright CN, Henderson KD, Sullivan-Halley J, et al. Long-term and recent recreational physical activity and survival after breast cancer: the California Teachers Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2851–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ligibel JA, Giobbie-Hurder A, Olenczuk D, et al. Impact of a mixed strength and endurance exercise intervention on levels of adiponectin, high molecular weight adiponectin and leptin in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1523–8. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ligibel JA, Campbell N, Partridge A, et al. Impact of a mixed strength and endurance exercise intervention on insulin levels in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:907–12. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stull VB, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Lifestyle interventions in cancer survivors: designing programs that meet the needs of this vulnerable and growing population. J Nutr. 2007;137:243S–8S. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.1.243S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, et al. Breast cancer: Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:122–92. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaufmann M, von Minckwitz G, Bear HD, et al. Recommendations from an international expert panel on the use of neoadjuvant (primary) systemic treatment of operable breast cancer: new perspectives 2006. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1927–34. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Im YH, Lee SH, et al. Evaluation of ER and Ki-67 proliferation index as prognostic factors for survival following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with doxorubicin/docetaxel for locally advanced breast cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:569–77. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4396–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polcher M, Friedrichs N, Rudlowski C, et al. Changes in Ki-67 labeling indices during neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer are associated with survival. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:555–60. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c104c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guarneri V, Piacentini F, Ficarra G, et al. A prognostic model based on nodal status and Ki-67 predicts the risk of recurrence and death in breast cancer patients with residual disease after preoperative chemotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1193–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nishimura R, Osako T, Okumura Y, Hayashi M, Arima N. Clinical significance of Ki-67 in neoadjuvant chemotherapy for primary breast cancer as a predictor for chemosensitivity and for prognosis. Breast Cancer. 2010;17:269–75. doi: 10.1007/s12282-009-0161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Billgren AM, Rutqvist LE, Tani E, Wilking N, Fornander T, Skoog L. Proliferating fraction during neoadjuvant chemotherapy of primary breast cancer in relation to objective local response and relapse-free survival. Acta Oncol. 1999;38:597–601. doi: 10.1080/028418699431186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vatten LJ, Holly JM, Gunnell D, Tretli S. Nested case-control study of the association of circulating levels of serum insulin-like growth factor I and i nsulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 with breast cancer in young women in Norway. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2097–100. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Espelund U, Cold S, Frystyk J, Orskov H, Flyvbjerg A. Elevated free IGF2 levels in localized, early-stage breast cancer in women. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;159:595–601. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, et al. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins 1 and 3 and breast cancer outcomes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;74:65–76. doi: 10.1023/a:1016075709022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibrahim YH, Yee D. Insulin-like growth factor-I and breast cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:944s–50s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodwin PJ, Ennis M, Pritchard KI, et al. Fasting insulin and outcome in early-stage breast cancer: results of a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:42–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnard RJ, Gonzalez JH, Liva ME, Ngo TH. Effects of a low-fat, high-fiber diet and exercise program on breast cancer risk factors in vivo and tumor cell growth and apoptosis in vitro. Nutr Cancer. 2006;55:28–34. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc5501_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Irwin ML, Varma K, Alvarez-Reeves M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of aerobic exercise on insulin and insulin-like growth factors in breast cancer survivors: the Yale Exercise and Survivorship study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:306–13. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Symmans WF, Peintinger F, Hatzis C, et al. Measurement of residual breast cancer burden to predict survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4414–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.6823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Irwin ML, Duggan C, Wang CY, et al. Fasting C-peptide levels and death resulting from all causes and breast cancer: the health, eating, activity, and lifestyle study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:47–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keinan-Boker L, Bueno De Mesquita HB, et al. Circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor I, its binding proteins −1,−2,−3, C-peptide and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:90–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen JA, Stolk RP, Pols HA, Grobbee DE, Lamberts SW. Serum total IGF-I, free IGF-I, and IGFB-1 levels in an elderly population: relation to cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:277–82. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williams NH, Hendry M, France B, Lewis R, Wilkinson C. Effectiveness of exercise-referral schemes to promote physical activity in adults: systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2007;57:979–86. doi: 10.3399/096016407782604866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM, Reid RD, et al. Predictors of follow-up exercise behavior 6 months after a randomized trial of exercise training during breast cancer chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114:179–87. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9987-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Del Rio G, Zironi S, Valeriani L, et al. Weight gain in women with breast cancer treated with adjuvant cyclophosphomide, methotrexate and 5- fluorouracil. Analysis of resting energy expenditure and body composition. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;73:267–73. doi: 10.1023/a:1015892714162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demark-Wahnefried W, Kenyon AJ, Eberle P, Skye A, Kraus WE. Preventing sarcopenic obesity among breast cancer patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy: results of a feasibility study. Clin Exerc Physiol. 2002;4:44–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]