Abstract

Background

Several cardiovascular risk factors have been associated with the risk of atrial fibrillation (AF). Limited and inconsistent evidence exists on the association of blood lipid levels and lipid lowering medication use with AF risk.

Methods and Results

We analyzed 13,969 participants (25% African-American, 45% men) free of AF at baseline from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Fasting HDL cholesterol (HDLc), LDL cholesterol (LDLc), triglycerides, and total cholesterol were measured at baseline (1987–89) and each of three follow-up visits. Incidence of AF was ascertained through 2007. The association of the use of statins and other lipid lowering medications with AF was estimated in 13,044 ARIC participants attending visit 2 (1990–92), adjusting for covariates from the previous visit. During a median follow-up of 18.7 years there were 1433 incident AF cases. Multivariable hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of AF associated with a one standard deviation increase in lipid levels were: HDLc: 0.97 (0.91–1.04); LDLc: 0.90 (0.85–0.96); total cholesterol: 0.89 (0.84–0.95); and triglycerides: 1.00 (0.96–1.04). Participants taking lipid lowering medications had an adjusted HR (95% CI) of AF of 0.96 (0.82–1.13) compared to those not on medications, while those taking statins had an adjusted HR of 0.91 (0.66–1.25) compared to those taking other lipid lowering mediations.

Conclusions

Higher levels of LDLc and total cholesterol were associated with a lower incidence of AF. HDLc and triglycerides, however, were not independently associated with AF incidence. No association was found between the use of lipid lowering medications and incident AF.

Keywords: lipids, epidemiology, atrial fibrillation, statins

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia, currently affecting over 2.3 million US adults, and that number is expected to more than double in the next 5 decades as the population ages.1 AF is associated with increased risks of heart failure, stroke and cardiovascular death.2 Major predictors for AF include age, white race / European ancestry, obesity, left ventricular hypertrophy, and hypertension, along with certain lifestyle factors.3–6 Many of these predictors are also risk factors for coronary heart disease (CHD) or heart failure (HF), which often precedes the onset of AF.2 Blood lipid levels, which are established risk factors for CHD, could also influence the risk of AF. In fact, low HDL cholesterol (HDLc) levels have been associated with a 20–40% increased risk of AF, with no association seen between triglyceride levels and the risk of AF. 7–9 However, limited and inconsistent data exist on the association of triglycerides, total cholesterol and LDLc cholesterol (LDLc) with incident AF, especially independently of other components of the metabolic syndrome. 10–14

Numerous studies have provided evidence of the effectiveness of statins in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, potentially beyond their lipid-lowering effect.15 Accordingly, it has been suggested that statins might be effective in preventing AF. 16 Randomized controlled trials have found that use of statins was significantly associated with a decreased risk of post-operative AF, and a decreased recurrence of AF.17, 18 Decreases in mortality and cardiovascular events have been observed in patients receiving statins after AF diagnosis.19 However, observational data and clinical trial evidence have produced mixed results regarding the impact of statins on the incidence of AF in otherwise healthy populations. An observational study reported statin use reduced the risk of developing AF independently of the reduction in serum cholesterol levels. 20 However, a large randomized clinical trial (ALLHAT) showed no relationship between randomly assigned pravastatin use and a reduction in incident AF, after a follow-up time of six years.8 These data are consistent with a meta-analysis in which the analysis of randomized controlled trials showed no significant effect of statins on AF incidence, but indicated statins significantly reduced the relative risk of AF in observational studies.21 To the best of our knowledge, no information exists on the effect of other lipid lowering medications on the risk of AF.

The present study estimates the association of participants’ blood lipid profile over time with the incidence of AF in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort, a community-based study of cardiovascular disease in the US. We also assess whether use of statins or other cholesterol lowering medications affects the risk of AF, taking advantage of the large number of incident AF cases and ample follow-up time in the ARIC cohort.

Methods

Study population

The ARIC study is a prospective cohort study of cardiovascular disease and atherosclerosis risk factors. Participants at baseline (1987–1989) included 15,792 men and women aged 45–64, recruited from four communities in the US (Washington County, MD; suburbs of Minneapolis, MN; Jackson, MS; Forsyth County, NC). Participants were mostly white in the Washington County and Minneapolis centers, only African-American in the Jackson center, and included both races in Forsyth County. After the initial assessment, study participants were examined three additional times (1990–92, 1993–95, 1996–98). Response rates for surviving participants at each exam were 93%, 86% and 80% respectively. Additionally, ARIC participants have received annual follow-up calls since baseline, and survivors have a response rate of ≥ 90%. The study was approved by institutional review boards at each participating center and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Ascertainment of atrial fibrillation

AF diagnoses were ascertained by three different sources in the ARIC study: electrocardiograms (ECG) performed at study visits, hospital discharge codes, and death certificates.3 At each ARIC study visit, a 10-second 12-lead ECG was performed using a MAC PC cardiograph (Marquette Electronics Inc, Milwaukee, WI) and transmitted to the ARIC ECG Reading Center for coding, interpretation and storage. All ECGs automatically coded as AF were visually checked by a trained cardiologist to confirm AF diagnosis.22

Annual follow-up calls and review of local hospital discharges identified hospitalizations in ARIC participants through the end of 2007. ICD-9-CM codes of 427.31 or 427.32 listed as a discharge diagnostic code identified AF cases. AF events associated with cardiac surgery were excluded in this study. Validity was sufficient as approximately 90% of the cases were confirmed in a physician review of discharge summaries from 125 possible AF cases.3 AF cases were also identified if codes ICD-9 427.3 or ICD-10 I48 were listed as a cause of death. Most incident AF cases (> 98%) in this analysis were identified from hospital discharge codes. In this analysis, the incidence date of AF was defined as the date for the first ECG showing AF, the first hospital discharge coded as AF or when AF was listed as a cause of death, whichever occurred earlier.

Assessment of lipid levels

Blood samples were collected at each visit following a fast of at least eight hours and sent to the ARIC Central Lipid Laboratory for processing. Detailed procedures are available elsewhere.23, 24 Briefly, total plasma cholesterol and triglycerides were determined by enzymatic methods, HDLc was measured after dextran-magnesium precipitation, and LDLc was calculated by the Friedewald equation25 in those with triglyceride levels under 400 mg/dL.

Assessment of lipid-lowering medication use

The use of lipid-lowering medications was self-reported and confirmed by checks on medications brought to each visit by the patient. Lipid medications were divided into two categories: statins and other lipid medications. Included in the “other” category were niacin (vitamin B3), bile sequestrants, fibrates, and other antihyperlipidemics. Participants taking both statins and another type of lipid lowering medication were considered to be in the statin category.

Measurement of other covariates

At each study visit, participants underwent a physical exam and provided self-reported information. Detailed procedures on covariate measurements are available elsewhere.23 At each visit, prevalent HF was defined as the reported use of HF medication in the previous two weeks, presence of HF according the Gothenburg criteria (only at the baseline visit), or having developed incident HF from the previous visit. 26 Incident HF was defined as the presence of ICD-9-CM code 428 in any hospitalization during follow-up.27 Prevalent CHD was defined as prior cardiovascular revascularization, physician-diagnosed myocardial infarction, or presence of a previous myocardial infarction by ECG and incident CHD was ascertained by the ARIC Morbidity and Mortality Classification Committee using data from follow-up calls, hospitalization records and death certificates.28 Prevalent stroke was defined as the self-reported physician diagnosis of a stroke prior to visit 1, and following visit 1 was adjudicated from diagnosis codes indicative of cerebrovascular disease.29 Incident stroke was defined as the first probable or definite hospitalized stroke occurring in a participant free of a history of diagnosed stroke at baseline.

Statistical analysis

Inclusion / exclusion criteria

Of the 15,792 participants who attended visit 1 in the ARIC study, we excluded individuals who were of a racial/ethnic group other than white or African-American and nonwhites in the Minneapolis and Washington County field centers (n=103), those with prevalent AF at visit 1 (n=37), low quality or missing ECG (n=309), those missing lipid levels (n=395), those non-fasting (n=558) and those missing covariates (n=14). For analysis of lipid levels, those taking cholesterol medications at visit 1 were also excluded (n=407; 20% statins). The final sample for lipid level analysis included 13,969 participants (25% African-American, 45% male). The association of use of cholesterol-lowering medications with AF was estimated in 13,044 ARIC participants using visit 2 as baseline and similar exclusion criteria. Beginning follow-up at visit 2 allowed us to adjust for lipid levels and covariates from visit 1 as potential confounders.

Lipid level analysis

We categorized individuals by lipid levels according to clinical categories outlined in the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines: HDLc categorized as: <40 mg/dL, 40–59 mg/dL, ≥60 mg/dL; LDLc: <100 mg/dL, 100–159 mg/dL, ≥160 mg/dL; total cholesterol: <200 mg/dL, 200–239 mg/dL, ≥240 mg/dL; triglycerides: <150 mg/dL, 150–199 mg/dL, ≥200 mg/dL. 30 For the analysis with lipid levels as a time-dependent exposure (see below), a measurement of one standard deviation (SD) increment of each lipid level was used to allow comparisons among different blood lipid levels. In an additional analysis, we examined the association of changes in LDLc levels from visit 1 to visit 4 with AF risk, adjusting for covariates from both visits along with baseline LDLc levels. P-values for trend were calculated including lipid levels as continuous variables in the models.

We estimated the association of baseline (visit 1) lipid levels with the incidence of AF using Cox proportional hazards models with time to AF as the main outcome variable. Follow-up time was defined as the time elapsed between baseline and date of AF incidence, death, lost to follow-up or December 31, 2007, whichever came earlier. The rate of AF was modeled using a Cox proportional hazards model with lipid levels as time-varying covariates. Models were adjusted for baseline covariates including age, sex, race, study site, education (less than completed high school, high school diploma, at least some college), income (<$16,000, $16,000–<$35,000, $35,000-<$50,000, ≥$50,000), and height (continuous), and were also adjusted for the following time-varying covariates: smoking (never, former, current), alcohol drinking (never, former, current), BMI (continuous), diabetes (dichotomous), systolic blood pressure (continuous), diastolic blood pressure (continuous), use of antihypertensive medications, use of cholesterol lowering medications, prevalent stroke, prevalent HF and prevalent CHD . An additional model was performed also adjusting for incident stroke, incident HF and incident CHD as time-varying covariates. The proportional hazards assumption was tested using time interaction terms and inspection of log negative log survival curves.

Because most AF events were identified from hospitalizations, we conducted two additional analyses to evaluate whether associations between lipid levels and AF risk would be biased because of the method of event ascertainment. First, we determined whether lipid levels were associated with incidence of any hospitalization, and compared those results with the association of lipids and AF. Second, we included any hospitalization as a time-dependent covariate in the models, to determine whether hospitalizations mediated any observed association between lipid levels and AF.

Lipid-lowering medication analysis

To measure the association between lipid medication use and the incidence of AF, visit 2 was used as baseline, and models were adjusted for covariates of interest from visit 1, using similar models as stated above, and in addition also adjusting for LDLc and triglycerides measured at the previous visit. The association between lipid medication use and incidence of AF was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models with time-varying medication use (visits 2, 3 and 4) and covariates to take into account changes in medication use over time.

In addition to the standard multivariable analyses for lipid medications, we conducted a secondary analysis using a propensity score approach. 31 We calculated an estimated propensity score as the probability of receiving treatment at visit 2 given covariates (previously mentioned) using a logistic model. Secondly, we performed two different analyses: (1) we conducted a standard Cox model adjusting for the propensity score, and (2) treated and untreated were matched on their continuous propensity score at a 4:1 ratio with nearest neighbor matching with no replacement for prior matched control, and analyzed in a Cox model. Follow-up for this analysis also started in visit 2 in order to adjust for other covariates measured in the previous visit, including LDLc and triglyceride levels.

We conducted stratified analyses by age and race categories in all lipid levels. Effect measure modification was formally tested including an interaction term between age and race variables and levels of each lipid measurement. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS v 9.2 (SAS Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Selected characteristics for ARIC participants by categories of total cholesterol are shown in Table 1. Older participants, women, African-Americans, and those with less education and income were more likely to have higher levels of total cholesterol. Diabetes, hypertension, prevalent CHD and prevalent HF were also associated with higher cholesterol.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of ARIC participants by total cholesterol levels, ARIC, 1987–1989.

| Total Cholesterol |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| <200 mg/dL <5.18 mmol/L |

200–239 mg/dL 5.18–6.21 mmol/L |

≥240 mg/dL ≥6.22 mmol/L |

|

| Number of participants | 5458 | 5246 | 3265 |

| Age, years | 53.2 (5.8) | 54.4 (5.7) | 55.3 (5.6) |

| Men, % | 48.1 | 44.3 | 39.1 |

| African-American, % | 26.5 | 22.3 | 27.9 |

| High school degree, % | 78.7 | 77.4 | 74.5 |

| Income ≥$50,000, % | 26.7 | 24.0 | 19.4 |

| Current smoker, % | 26.7 | 24.4 | 26.6 |

| Current alcohol use, % | 57.6 | 56.9 | 55.1 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.4 (5.5) | 27.6 (5.4) | 27.9 (5.0) |

| Height, cm | 169.4 (9.3) | 168.4 (9.3) | 167.0 (9.2) |

| Diabetes, % | 8.6 | 9.8 | 12.2 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 119.2 (18.4) | 121.3 (18.6) | 123.3 (19.2) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 73.0 (11.3) | 73.7 (11.1) | 74.6 (11.2) |

| Anti-hypertensive medications, % | 26.3 | 29.0 | 32.9 |

| Prevalent coronary heart disease, % | 3.4 | 4.5 | 5.1 |

| Prevalent stroke, % | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| Prevalent heart failure, % | 3.9 | 4.3 | 4.2 |

Values correspond to mean (SD) or percentage. BMI: body mass index

Blood lipids and AF risk

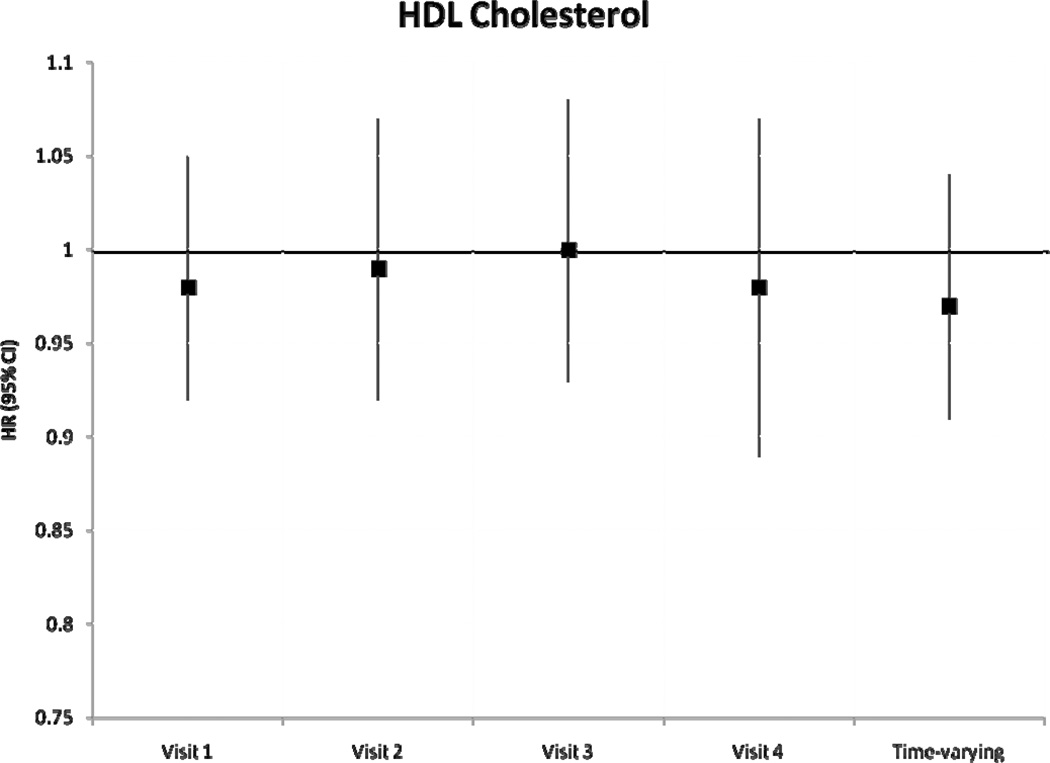

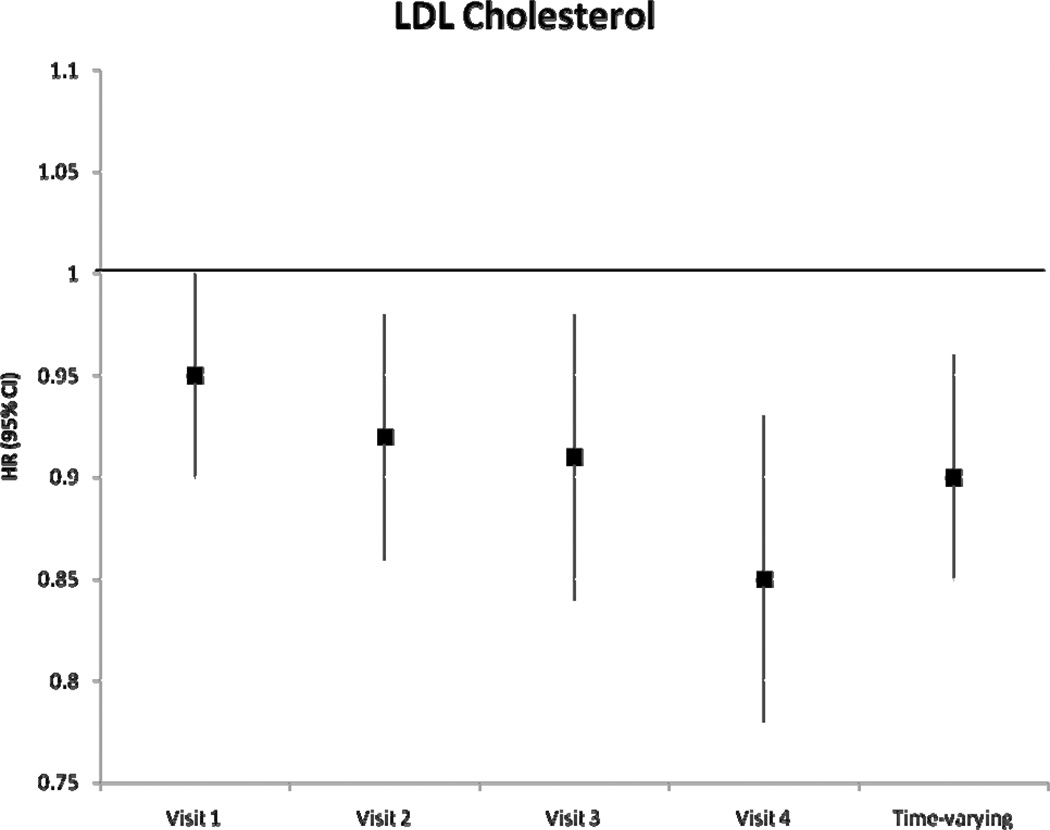

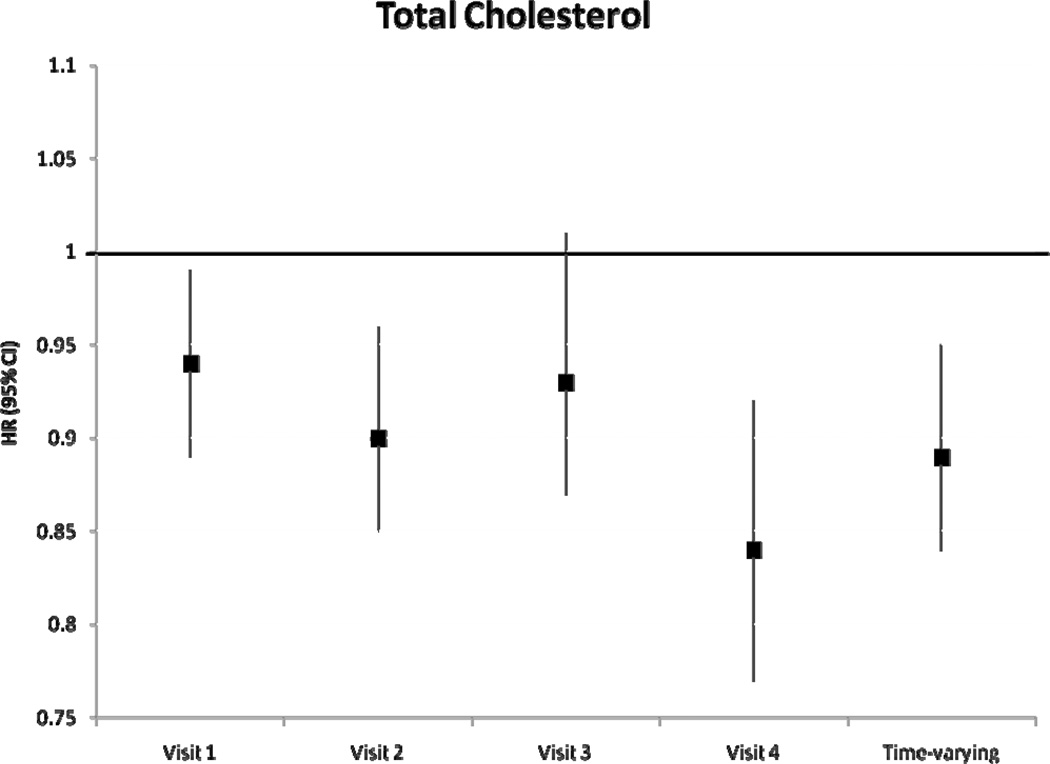

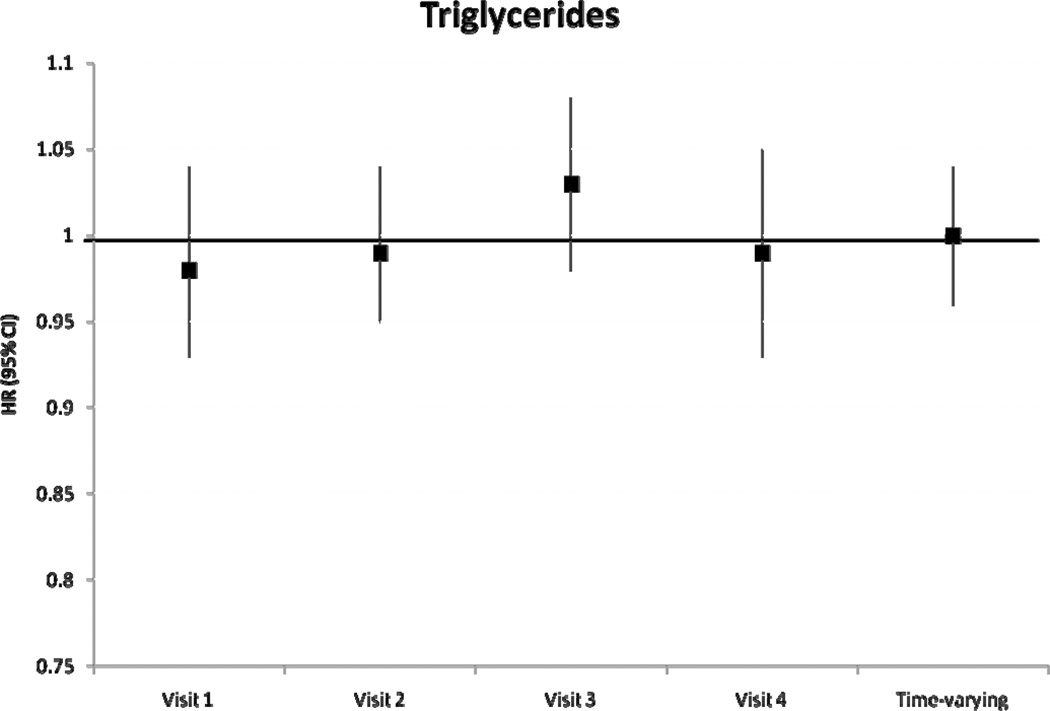

During a median follow-up of 18.7 years, we identified 1433 incident AF cases. After adjustment for potential confounders and intermediates, there was no significant association between baseline levels of HDLc and triglycerides with incident AF (table 2). Higher levels of LDLc and total cholesterol at baseline were associated with a lower risk of incident AF. Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) of AF in individuals with LDLc 100–159 mg/dL was 0.84 (0.72–0.97) and in LDLc ≥160 mg/dL was 0.85 (0.72–1.01) compared to those with LDLc levels <100 mg/dL (p for trend=0.06). Compared to those with total cholesterol levels <200 mg/dL, the HR(95% CI) of AF was 0.88 (0.76–1.01) in those with levels ≥240 mg/dL (p for trend=0.03). Models not adjusting for prevalent stroke, HF and CHD, and also models additionally adjusting for incident stroke, HF and CHD produced similar results. Results of the association between incident AF and each lipid level measurement at visits 2–4 were similar and are shown in Figure 1. A significant inverse association was seen between LDLc and total cholesterol and incident AF in most visits, with stronger associations in later visits. Results were comparable when we considered lipid levels as time-dependent exposures, also shown in Figure 1. The HR (95% CI) of AF by one standard deviation increment in time-varying HDLc and triglyceride measurements were 0.97 (0.91–1.04) and 1.00 (0.96–1.04), respectively. HR (95% CI) in time-varying LDLc measurements was 0.90 (0.85–0.96) and in total cholesterol was 0.89 (0.84–0.95). In analyses including only AF events identified in study ECGs (n=117), the HR (95% CI) of AF was 0.79 (0.63–0.98) for LDLc and 0.75 (0.60–0.93) for total cholesterol. Adjustment for exercise in the models did not change the significance of the association. An additional analysis was performed examining the change in LDLc from visit 1 to visit 4. After excluding those on cholesterol medications, and after adjustment for visit 1 and visit 4 covariates and baseline LDLc levels, the HR (95% CI) for 1 mmol/L change of LDLc was 0.79 (0.69–0.90). These results indicate that the larger the decrease in LDLc from visit 1 to visit 4, the lower the risk of AF. LDLc was not associated with overall risk of hospitalizations (HR 0.98, 95% CI 0.96–1.00, for 1-SD increment), and adjustment for hospitalizations as a time-dependent covariate did not change the association between LDLc and AF risk (HR 0.91, 95% CI 0.86–0.97 for 1-SD LDLc increment as a time-dependent covariate).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of atrial fibrillation by baseline levels of blood lipids, categorized by clinically relevant categories, ARIC, 1987–2007

| HDLc | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <40 mg/dL | 40–59 mg/dL | ≥60 mg/dL | P for trend | |

| AF cases | 485 | 665 | 283 | |

| Person-years | 58815 | 111506 | 66320 | |

| AF incidence* | 6.03 | 4.83 | 3.89 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 0.78 (0.69–0.88) | 0.63 (0.53–0.74) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 (REF) | 0.97 (0.85–1.09) | 1.00 (0.84–1.19) | 0.56 |

| LDLc | ||||

| <100 mg/dL | 100–159 mg/dL | ≥160 mg/dL | P for trend | |

| AF cases | 217 | 825 | 391 | |

| Person-years | 38202 | 138779 | 59659 | |

| AF incidence* | 5.15 | 4.53 | 4.60 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 0.87 (0.75–1.01) | 0.88 (0.74–1.04) | 0.15 |

| Model 2 | 1 (REF) | 0.84 (0.72–0.97) | 0.85 (0.72–1.01) | 0.06 |

| Total Cholesterol | ||||

| <200 mg/dL | 200–239 mg/dL | ≥240 mg/dL | P for trend | |

| AF cases | 547 | 553 | 333 | |

| Person-years | 92693 | 88838 | 55110 | |

| AF incidence* | 4.87 | 4.68 | 4.36 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 0.96 (0.85–1.08) | 0.89 (0.77–1.02) | 0.03 |

| Model 2 | 1 (REF) | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) | 0.88 (0.76–1.01) | 0.03 |

| Triglycerides | ||||

| <150 mg/dL | 150–199 mg/dL | ≥200 mg/dL | P for trend | |

| AF cases | 977 | 228 | 228 | |

| Person-years | 177413 | 33456 | 25771 | |

| AF incidence* | 4.41 | 4.73 | 6.04 | |

| Model 1 | 1 (REF) | 1.08 (0.93–1.24) | 1.40 (1.21–1.62) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | 1 (REF) | 0.87 (0.75–1.00) | 1.02 (0.88–1.18) | 0.52 |

Per 1,000 person-year. Adjusted for age, sex, and race.

P for trend is the association with linear continuous levels

Model 1: Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for age, sex and race.

Model 2: Model 1, additionally adjusted for study site, education, income, height, smoking status, drinking status, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes, prevalent stroke, prevalent heart failure and prevalent coronary heart disease.

Figure 1.

Hazard Ratio and 95% confidence intervals of atrial fibrillation according to lipid level measurements at each visit, and as a time-varying variable, ARIC, 1987–2007. Results from separate Cox proportional hazard models adjusted for age, sex, race, study site, education, income, height, smoking status, drinking status, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes, prevalent stroke, prevalent heart failure, prevalent coronary heart disease, and use of cholesterol medications

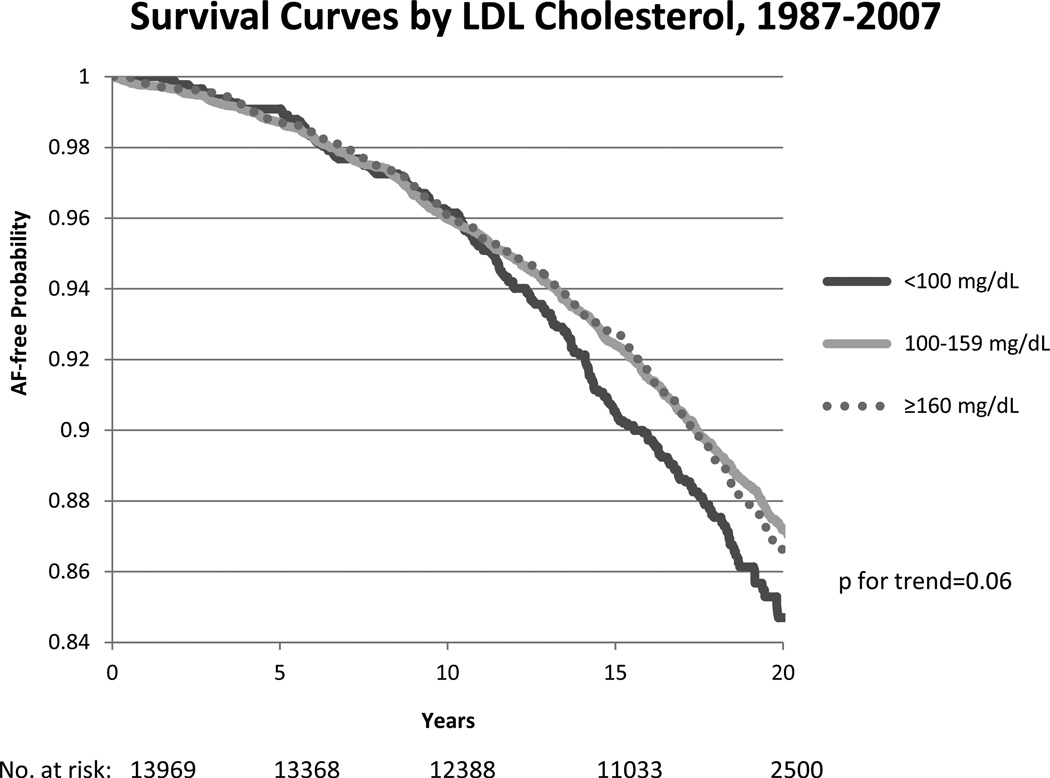

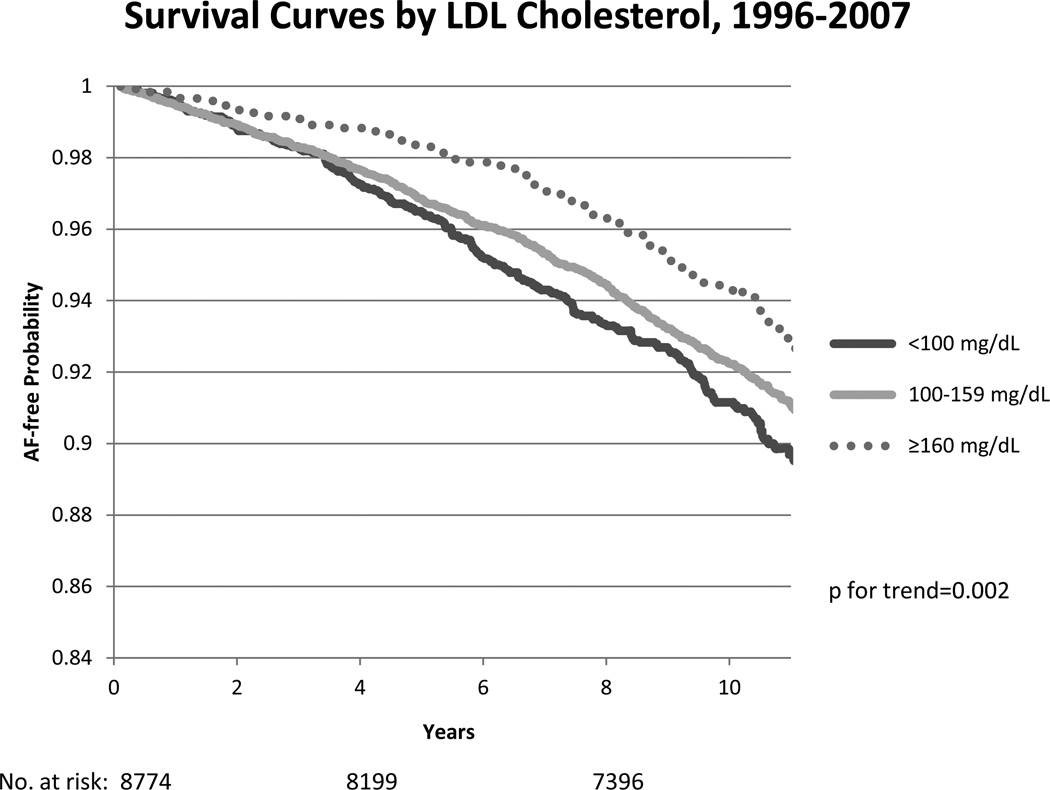

AF-free survival curves from visit 1 and visit 4 by LDLc cholesterol levels are shown in figure 2, with higher survival in those with higher LDLc. There was no significant age or race interaction between HDLc, LDLc and total cholesterol levels. However, the association of triglyceride levels with AF risk varied by race (p=0.02), with a stronger association in African-Americans compared to whites (HR (95%CI) = 1.14 (1.03–1.26) and 0.99 (0.94–1.03), respectively).

Figure 2.

Kaplan Meier survival curves for atrial fibrillation (AF) by categories of LDLc cholesterol (<100, 100–159, ≥160 mg/dL) from baseline (top panel) and from visit 4 (bottom panel), ARIC 1987–2007 and 1996–2007, respectively. Cox proportional hazards model excluding those on cholesterol-lowering medications at baseline, and adjusted for age, sex, study site, education, income, height, smoking status, drinking status, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes, prevalent stroke, prevalent heart failure, and prevalent coronary heart disease. P for trend is considered across categories. The number of subjects at risk throughout the duration of the study follow-up are shown on the x-axis.

Lipid-lowering medication use and AF risk

We assessed the association of use of cholesterol medications with AF risk, considering visit 2 as baseline while adjusting for covariates from the previous visit. Among the 13,044 eligible participants, 2102 were on some cholesterol-lowering medication at one or more visits, with 68% of those taking statins at some point (39% at visit 2, 59% at visit 3, 80% at visit 4). There were 1311 incident AF cases identified, and of those occurring in cholesterol medication users (278 events), 68% occurred in those taking statins. After multivariable adjustment, there was no association between time-varying cholesterol medication use across visits and the incidence of AF with a HR (95% CI) of 0.96 (0.82–1.13) compared to those not on cholesterol-lowering medications (table 3). There was also no association between those taking statins compared to those taking other cholesterol medications, HR (95% CI) = 0.91 (0.66–1.25). Models not adjusting for prevalent stroke, heart disease and CHD, and also models additionally adjusting for incident stroke, heart disease and CHD produced similar results.

Table 3.

Hazard ratios (95% confidence interval) of atrial fibrillation by lipid medication use over time, ARIC, 1990–2007

| No Cholesterol Medications |

Any Cholesterol medications | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 10942 | 2102 |

| AF cases | 1033 | 278 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | 1(REF) | 0.96 (0.82–1.13) |

| Other Cholesterol Medications |

Statins | |

| Number of participants | 666 | 1436 |

| AF cases | 89 | 189 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI)* | 1 (REF) | 0.91 (0.66–1.25) |

Cox proportional hazard model with time-varying medication use and adjusted for age, sex, race, study site, education, income, and time-varying (from the previous visit) height, smoking status, drinking status, body mass index, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, use of antihypertensive medication, diabetes, prevalent stroke, prevalent heart failure, prevalent coronary heart disease, LDLc cholesterol and triglyceride levels

A secondary analysis was performed using propensity scores calculated at visit 2. In a standard Cox model, the propensity score-adjusted HR (95% CI) was 1.09 (0.88–1.34) comparing lipid-lowering medication use versus non-users, and when matched 4:1 (not-treated: treated) by propensity score, results were similar HR (95% CI) = 1.03 (0.89–1.20).

Discussion

In this population-based prospective study, we found no independent association between HDLc or triglycerides and incidence of AF, while lower levels of LDLc and total cholesterol were associated with a higher AF risk. We also found no independent association between lipid-lowering medications, including statins, and the risk of AF. These associations were independent of lifestyle factors, clinical factors and cardiovascular disease, and were similar with regards to whites and African Americans.

Blood lipid levels and AF

The relationship between lipid levels and AF risk has not been extensively addressed. Previous publications reported low HDLc levels were associated with a 20–40 % higher risk of AF; 7–9 however, residual confounding could have been responsible for that association. In our analysis, an initial association between HDLc and AF risk disappeared after adjustment for a wide selection of potential confounders. Similar results were observed for triglycerides.

The inverse association of LDLc and total cholesterol with AF risk is intriguing, and has been previously seen in an analysis of the Cardiovascular Health Study, which included individuals aged 65 and older.11 Similar results were found in two Japanese populations, in which individuals with hypercholesterolemia had a 25% lower odds of developing AF, and an 8% reduction in AF risk with each 10% increase in LDLc.9, 32 Notably, this association was stronger in older individuals, consistent with our results of stronger inverse associations in later ARIC visits. No clear mechanism exists to explain this association, however. Sub-clinical hyperthyroidism might be potentially responsible, since hyperthyroidism reduces levels of total and LDLc cholesterol,33 and is associated with increased risk of AF.34 Unfortunately, we do not have information on thyroid profiles in ARIC participants. Blood lipids could also impact the composition of cell membranes, which is a major determinant of cell excitability. In vitro studies have shown that cholesterol modulates the distribution and function of some ion channels potentially involved in the occurrence of AF, such as the Kv1.5 potassium channel.35, 36 Whether this mechanism explains the observed association is hypothetical and requires further research.

Lipid lowering medications and AF

Published reports addressing the relationship between statins and AF have provided inconsistent results and the conclusions tend to be different based on clinical trials (no association) or observational studies (reduced AF risk).21 This study provided results consistent with those seen in most randomized clinical trials, and indicated no relationship between statin use or any lipid-lowering medication use and the risk of AF. During the years the ARIC visits were conducted (1987–1998) statins were gaining in popularity, and that, combined with the participants getting older, meant the majority of statin users were not taking them until around visit 4 (1996–98). There have been no study visits since 1998, so we were unable to determine how many of the participants with incident AF were receiving statins or lipid-lowering medications in the years between visit 4 and the year in which their AF occurred.

Strengths and limitations

Some other study limitations should be noted. Asymptomatic AF and AF managed exclusively in an outpatient setting could not be identified, as most of our incident AF cases were ascertained from hospitalization discharge records. However, it has been shown the incidence rates of AF in the ARIC study are consistent with other population-based studies, and the validity of AF ascertainments using hospitalizations is acceptable.3 In a sub-analysis in this study comparing AF ascertained from hospital records versus ECGs, there was an even stronger inverse association seen between LDLc (HR=0.79 for ECGs; HR=0.90 for hospital records) and total cholesterol (HR=0.75 for ECGs; HR=0.89 for hospital records) and incident AF in the ECG group, thus supporting evidence that AF ascertained from hospitalizations is acceptable. Also, LDLc levels were not associated with the risk of hospitalization, and adjustment for incident hospitalizations before AF incidence or censoring did not change the association between LDLc and AF. There is also the possibility those with dyslipidemia have more paroxysmal AF that was not captured by our AF ascertainment process. Other limitations include the possible misclassification of exposures, both lipid levels and lipid-lowering medications, due to unmeasured changes between visits. Along with no data on thyroid hormones, which might confound our results, the ARIC study also does not contain information on the dose of statins or other lipid medications. Higher doses have a stronger effect on cholesterol levels and other processes (such as inflammation in the case of statins), and therefore different doses may affect differentially the incidence of AF. Also, we cannot determine the impact of lifestyle changes a patient may incorporate to become healthier after discovering they have high cholesterol. Despite these limitations, our study has important strengths including a large sample size, a long follow-up, an elevated number of AF events, a biracial sample, and an extensive list of measured covariates.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we found that higher levels of LDLc and total cholesterol were associated with a lower incidence of AF independently of other risk factors. HDLc and triglycerides, however, were not independently associated with AF incidence after multivariable adjustment. Future research should replicate these results and study potential mechanisms. Additionally, no association was found between lipid-lowering medication, including statins, and the incidence of AF. At this time, there is still insufficient data to recommend the use of statins solely for AF prevention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions.

Funding Sources: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contracts N01-HC55015, N01-HC55016, N01-HC55018, N01-HC55019, N01-HC55020, N01-HC55021, and N01-HC55022. This study was additionally supported by grants RC1-HL099452 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and 09SDG2280087 from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Go AS, Hylek EM, Phillips KA, Chang Y, Henault LE, Selby JV, Singer DE. Prevalence of diagnosed atrial fibrillation in adults: national implications for rhythm management and stroke prevention: the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors in Atrial Fibrillation (ATRIA) Study. JAMA. 2001;285:2370–2375. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.18.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort. The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alonso A, Agarwal SK, Soliman EZ, Ambrose M, Chamberlain AM, Prineas RJ, Folsom AR. Incidence of atrial fibrillation in whites and African-Americans: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J. 2009;158:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanoski CA. Prevalence, pathogenesis, and impact of atrial fibrillation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2010;67:S11–S16. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang TJ, Parise H, Levy D, D'Agostino RBS, Wolf PA, Vasan RS, Benjamin EJ. Obesity and the risk of new-onset atrial fibrillation. JAMA. 2004;292:2471–2477. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.20.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcus GM, Alonso A, Peralta CA, Lettre G, Vittinghoff E, Lubitz SA, Fox ER, Levitzky YS, Mehra R, Kerr KF, Deo R, Sotoodehnia N, Akylbekova M, Ellinor PT, Paltoo DN, Soliman EZ, Benjamin EJ, Heckbert SR. Candidate-Gene Association Resource (CARe) Study. European ancestry as a risk factor for atrial fibrillation in African Americans. Circulation. 2010;122:2009–2015. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.958306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamberlain AM, Agarwal SK, Ambrose M, Folsom AR, Soliman EZ, Alonso A. Metabolic syndrome and incidence of atrial fibrillation among blacks and whites in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Am Heart J. 2010;159:850–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haywood LJ, Ford CE, Crow RS, Davis BR, Massie BM, Einhorn PT, Williard A. ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Atrial fibrillation at baseline and during follow-up in ALLHAT (Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:2023–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe H, Tanabe N, Yagihara N, Watanabe T, Aizawa Y, Kodama M. Association Between Lipid Profile and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation. Circ J. 2011 doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goonasekara CL, Balse E, Hatem S, Steele DF, Fedida D. Cholesterol and cardiac arrhythmias. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2010;8:965–979. doi: 10.1586/erc.10.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psaty BM, Manolio TA, Kuller LH, Kronmal RA, Cushman M, Fried LP, White R, Furberg CD, Rautaharju PM. Incidence of and risk factors for atrial fibrillation in older adults. Circulation. 1997;96:2455–2461. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guize L, Pannier B, Thomas F, Bean K, Jego B, Benetos A. Recent advances in metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;101:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.acvd.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe H, Tanabe N, Watanabe T, Darbar D, Roden DM, Sasaki S, Aizawa Y. Metabolic syndrome and risk of development of atrial fibrillation: the Niigata preventive medicine study. Circulation. 2008;117:1255–1260. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.744466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A, Lappas G. Hospitalizations for atrial fibrillation in the general male population: morbidity and risk factors. J Intern Med. 2001;250:382–389. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2001.00902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Banach M, Mikhailidis DP, Kjeldsen SE, Rysz J. Time for new indications for statins? Med Sci Monit. 2009;15:MS1–MS5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Schram G, Lavoie J, Nattel S. Effect of simvastatin and antioxidant vitamins on atrial fibrillation promotion by atrial-tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Circulation. 2004;110:2313–2319. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000145163.56529.D1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fauchier L, Pierre B, de Labriolle A, Grimard C, Zannad N, Babuty D. Antiarrhythmic effect of statin therapy and atrial fibrillation a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:828–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adam O, Neuberger HR, Bohm M, Laufs U. Prevention of atrial fibrillation with 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Circulation. 2008;118:1285–1293. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.760892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Badheka AO, Rathod A, Kizilbash MA, Garg N, Mohamad T, Afonso L, Jacob S. Impact of lipid-lowering therapy on outcomes in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:1768–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Young-Xu Y, Jabbour S, Goldberg R, Blatt CM, Graboys T, Bilchik B, Ravid S. Usefulness of statin drugs in protecting against atrial fibrillation in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:1379–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu T, Li L, Korantzopoulos P, Liu E, Li G. Statin use and development of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials and observational studies. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126:160–170. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soliman EZ, Prineas RJ, Case LD, Zhang ZM, Goff DC., Jr Ethnic distribution of ECG predictors of atrial fibrillation and its impact on understanding the ethnic distribution of ischemic stroke in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2009;40:1204–1211. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.534735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manual 8. National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH); Lipid and Lipoprotein Determinations 1987. Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eriksson H, Caidahl K, Larsson B, Ohlson LO, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Svardsudd K. Cardiac and pulmonary causes of dyspnoea--validation of a scoring test for clinical-epidemiological use: the Study of Men Born in 1913. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:1007–1014. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a062365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loehr LR, Rosamond WD, Chang PP, Folsom AR, Chambless LE. Heart failure incidence and survival (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study) Am J Cardiol. 2008;101:1016–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.White AD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Sharret AR, Yang K, Conwill D, Higgins M, Williams OD, Tyroler HA. Community surveillance of coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: methods and initial two years' experience. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:223–233. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosamond WD, Folsom AR, Chambless LE, Wang CH, McGovern PG, Howard G, Copper LS, Shahar E. Stroke incidence and survival among middle-aged adults: 9-year follow-up of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort. Stroke. 1999;30:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Third Report of the Expert Panel on Detection. Evaluation, and Treatment of the High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III): Executive Summary. Available at: http://wwwnhlbinihgov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3_rpthtm. Accessed October 9 2010.

- 31.Oakes JM, Church TR. Invited commentary: advancing propensity score methods in epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1119–1121. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm072. discussion 1122–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iguchi Y, Kimura K, Shibazaki K, Aoki J, Kobayashi K, Sakai K, Sakamoto Y. Annual incidence of atrial fibrillation and related factors in adults. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duntas LH. Thyroid disease and lipids. Thyroid. 2002;12:287–293. doi: 10.1089/10507250252949405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heeringa J, Hoogendoorn EH, van der Deure WM, Hofman A, Peeters RP, Hop WC, den Heijer M, Visser TJ, Witteman JC. High-normal thyroid function and risk of atrial fibrillation: the Rotterdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2219–2224. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.20.2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abi-Char J, Maguy A, Coulombe A, Balse E, Ratajczak P, Samuel JL, Nattel S, Hatem SN. Membrane cholesterol modulates Kv1.5 potassium channel distribution and function in rat cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2007;582:1205–1217. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Balse E, El-Haou S, Dillanian G, Dauphin A, Eldstrom J, Fedida D, Coulombe A, Hatem SN. Cholesterol modulates the recruitment of Kv1.5 channels from Rab11-associated recycling endosome in native atrial myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14681–14686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902809106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]