Abstract

Addressing global health disparities in the developing world gained prominence during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The HIV/AIDS epidemic triggered much interest in and funding for health improvement and mortality reduction in low- and middle-income nations, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Alliances between U.S. academic medical centers and African nations were created through the departments of internal medicine and infectious disease. However, the importance of addressing surgical disease as part of global public health is becoming recognized as part of international health development efforts. We propose a novel model to reduce the global burden of surgical diseases in resource poor settings by incorporating a sustained institutional surgical presence with our residency training experience by placing a senior surgical resident to provide continuity of care and facilitate training of local personnel. We present the experiences of the University of North Carolina (UNC) Department of Surgery as part of the UNC Project in Malawi as an example of this innovative approach.

Introduction

The past two decades have seen an exponential rise in global health funding and in the number of U.S. medical programs involved in research and education efforts in the developing world. In particular, these efforts have targeted HIV/AIDs in resource poor settings, including sub-Saharan Africa [1]. While alliances between U.S. academic medical centers and African nations contributed greatly to providing clinical care and improving public health in the resource poor setting, it is becoming more apparent that addressing surgical disease is a key component of global public health [2, 3]. An estimate of global burden of disease (GBD) suggests that 11% of the GBD is attributable to surgical conditions [4]. This total is composed of injuries (38%), malignancies (19%), congenital anomalies (9%), complications of pregnancy (6%), cataracts (5%), and perinatal conditions (4%). A surgical condition is broadly defined as any condition for which the most potentially effective treatment is an intervention that requires suture, incision, excision, manipulation, or other invasive procedure that usually, but not always, requires anesthesia [5].

Malawi’s dual dilemma: high burden, few resources

By region, the most surgical disability adjusted life years (DALYs) lost are in Southeast Asia (48 million); however, Africa has the highest ratio of surgical DALYs lost per 1,000 people. Previous estimates suggest a rapid rise in non-communicable diseases in low and middle-income nations over the next decades [6]. In the face of this changing demographic of disease, many African nations are handicapped by their lack of human resources. The shortage of physicians and nurses in Africa is well documented; Africa bears nearly 25% of the global burden of disease with only 2% of the global health workforce [7]. Meanwhile, there is a paucity of data on the deficit in human resources for surgical care [8]. Africa has approximately 1% of the number of surgeons of the United States [9]. The UNC–Malawi Surgical Initiative (MSI) has addressed the burden of surgical disease in the resource limited setting of Malawi by placing a senior surgical resident in-country year-round; this constant presence provides continuity in research, education, and clinical care and is a foundation for shorter visits by senior UNC surgical specialists.

The UNC–Malawi collaboration

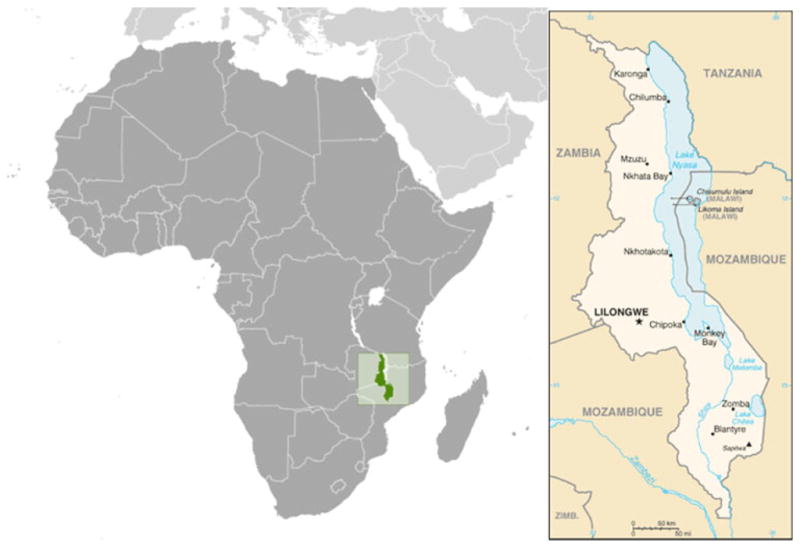

Malawi is a landlocked nation with a population of 14 million in sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 1). Geographically, its most prominent feature is Lake Nyasa, which is 580 km long; however socioeconomically it is known as one of the sub-Saharan nations hardest hit by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with a prevalence of 11.9% and resulting population life expectancy of 43.8 years [11]. Its major cities are Blantyre and the capital, Lilongwe. The UNC Project is a long-standing research and clinical program in Malawi, led by the Division of Infectious Diseases at UNC. There are multiple departments involved in this effort, of which the Department of Surgery is a relatively new partner.

Fig. 1.

Map of Malawi [10]

The presence of UNC in Lilongwe, Malawi, began in 1992 with the design of a sexually transmitted infection treatment program [12]. Over the ensuing decade this relationship expanded to include free HIV testing and counseling, and the establishment of permanent infrastructure and staff. Personnel from UNC work in close proximity with clinical staff at Kamuzu Central Hospital (KCH), which not only has active outpatient clinics but also has a busy trauma/emergency department staffed by its own surgeons.

Since 2006, faculty from the UNC Department of Surgery became interested in expanding the UNC Project-Malawi activities to include research, training, and clinical work within the Department of Surgery at KCH, particularly with regard to trauma/emergency services. Activities include research in trauma, particularly road traffic injuries and burns care, training of local surgeons in subspecialty care, and providing instruction in basic surgical care and technique to clinical officers (COs, non-physician clinicians), who provide the majority of medical care at local district hospitals. [13]. For surgery departments considering an investment in global health, the key concerns are designating the appropriate level of surgical personnel, providing a continuity of services, and not undermining pre-existing local surgical services. In Malawi, as in much of sub-Saharan Africa, a tiered hospital system exists with tertiary care provided at central hospitals in major cities such as Blantyre and the capital, Lilongwe, while most basic medical care is provided at the 21 district hospitals. These district hospitals have one non-surgeon physician, and this person is often recently out of internship yet designated the district health officer (DHO) [13]. Assisting this DHO are COs who have only three or four years of practical training. Any complicated surgical care is referred to one of four central hospitals in Blantyre, Zomba, Mzuzu, and Lilongwe. In order to make a sustainable impact on the surgical care provided to the majority of the populace, our efforts in Malawi needed to address both the central hospitals and the district hospitals through both service and more importantly education.

Strategy for improving surgical care

The UNC-Department of Surgery bases its efforts within KCH. Initially, UNC provided subspecialty care by having faculty from the departments of general surgery, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery travel to Malawi and perform complex operations with local surgeons that could not previously be undertaken due to lack of equipment and/or specialty training. The UNC faculty also instructed local surgeons in specialty surgical skills that could be applied in a resource poor setting. The exchange of ideas and the differing perspectives in surgical care unique to the developing world were also instructive to UNC faculty, and highlighted the need for continuity between the surgical services provided by the visiting American teams.

The UNC solution was to place a senior surgical resident in his/her research years at KCH for 2 years as part of a surgical disease assessment project. This resident would also support the KCH surgical staff in their clinical activities. Surgical residents have recently shown growing interest in working in developing countries during residency training [14]. The UNC Department of Surgery harnessed this interest and provided a structured overseas opportunity for surgical residents to gain international health experience while also contributing to the overall sustainability of the UNC presence in Lilongwe. The goal is to maximize the experience of the resident trainee as well as the benefit to the host nation.

Oversight of the resident trainee is provided by fully trained surgeons at KCH as well as UNC surgical faculty. The presence of UNC surgery resident in Malawi is primarily aimed at assessing local burden of surgical disease. Initially there were only three surgeons at KCH and the first UNC resident in 2008 began by assessing epidemiology and characteristics of trauma presenting to KCH. A trauma surveillance registry was created that tracked the types of trauma-related injuries seen by KCH in order to better allocate resources. Data from the registry were compared to road traffic crash data collected by the Lilongwe police department. Preliminary analysis indicates a predominance of injuries in young males and children, as well as an underestimation of DALYs lost when compared to World Health Organization (WHO) data [15]. Analysis also shows the burden of trauma is being underrepresented because many injuries manifest long after the incident because travel distances to medical care are great. Trauma victims who die because of the delay in getting treatment are taken directly to the KCH morgue and are missed by the trauma registry. This gap in the data gathering highlighted the need for multiple data sources.

Recognizing this loophole in the KCH trauma registry, the UNC-MSI commenced a second arm of the trauma assessment project in March 2010 by evaluating cause of death for bodies brought directly to the morgue, using the WHO verbal autopsy tool [16]. The verbal autopsy tool uses interviews with family members or close associates of the deceased to determine cause of death; the goal is to capture trauma-related injury deaths that are unaccounted for by the trauma registry. This study is still in the validation phase.

Since 2008, one UNC surgical resident, Jonathan Samuel, completed his research years at the UNC-Malawi Surgical Initiative with a second resident, Javeria Qureshi, commencing in July 2010. Dr. Samuel’s on the ground presence allowed for a sustained assessment of burden of injury, resulting in the evolution of trauma assessment from solely hospital based to include data from the Malawi Road Traffic Council and, most recently, the hospital morgue. In addition, placing a UNC resident on the ground at KCH led to an educational needs assessment of clinical officers (CO). This led to the creation of a curriculum to instruct CO students at the Malawi College of Health Sciences in basic surgical care, as well as the institution of a surgical quality assessment program at KCH. This began with conducting 2–3 didactic sessions per week given to CO students in their second or third years at the Malawi College of Health Sciences. The sessions focused on surgical disease in the resource limited setting, emphasizing skills that would allow COs to adequately triage patients while sole practitioners at district hospitals. Lecture topics cover basic topics in general surgery, such as bowel obstruction, perianal conditions, and the management of hernias. This series of lectures is slowly being transformed into a curriculum, using input from the first cadre of COs. Taking into account the dearth of educational opportunities for DHOs, the UNC resident also travels to various district hospitals to educate about basic surgical care and perform a needs assessment at the district level. These opportunities could not have developed without having a continuing UNC surgical presence in the person of that resident, whose role allows for continuing evaluation and a sustainable educational presence.

Opportunities and challenges

As documented in other international surgical resident experiences [17], the clinical opportunities for the UNC surgical resident have been phenomenal. Working with KCH surgeons, without access to the multimodal imaging technology accessible at most U.S. hospitals, has allowed for a honing of clinical skills with regard to the physical exam as well as optimizing surgical technique to fully utilize meager resources. The educational experience of the UNC surgical resident has been enhanced by working with KCH surgeons who have spent a lifetime operating in resource limited settings. Dealing with breast cancer at advanced stages, as well as managing mass casualties from road traffic crashes, are unique experiences that develop leadership skills in UNC surgical residents.

The UNC-Malawi Surgical Initiative also elucidates the hurdles to a sustained institutional surgical presence in the international setting. The increasing popularity of global health within U.S. medical centers has led to many organizations on the ground, each with its own well-intentioned projects, some of which may inadvertently compete with indigenous medical efforts. For example, UNC has a long presence in Malawi via research and clinical work in Lilongwe. However, educational efforts of the UNC-Malawi Surgical Initiative have highlighted a previous ignorance of the Malawi medical landscape. While training COs greatly benefits a populace with a dearth of medical providers, it also shows the need for an indigenous surgical residency. However, geography has been a challenge to this effort, as the Malawi College of Medicine is based in Blantyre, and the distance from KCH disconnects many medical students from the UNC surgical efforts. Recognizing the barriers placed by geography and previously established alliances has led to the evolution of the UNC-Malawi Surgical Initiative.

Our experience demonstrates how surgical residents can be the fulcrum, balancing relationships between U.S. academic departments of surgery and hospitals in low-income countries within an institutional cross-departmental relationship. However, much work remains to be done. The assessment of trauma-related injuries continues in Malawi, and the next phase of CO training is to make the transition from a series of lectures to a reproducible curriculum that can be used by other departments of surgery. In addition, we are expanding our education efforts to develop a surgical residency in Malawi, thereby strengthening ties with the Malawi College of Medicine. Already we have seen the fruits of this effort, as the program has attracted U.S. faculty interested in practicing fulltime at KCH. University of North Carolina medical students have also benefited by having the stable presence of a UNC surgical resident as a mentor and advocate during their elective time at KCH. A surgical resident’s presence has facilitated more UNC medical students completing surgical electives in Malawi, and the UNC-Malawi Surgical Initiative is one of the most attractive features of the UNC surgical residency. We plan not only to improve clinical care at KCH but to develop sustainable interest in global health among both medical students and surgical residents.

As relationships between U.S. academic medical centers and low-income nations continue to evolve, new models to facilitate research and education will be required. Using a senior surgical resident to build this relationship has been effective for the UNC-Malawi Surgical initiative. This experience allows for evolution of research projects, as well as the performance of essential needs assessments. While there are multiple collaborations between the U.S. medical community and international partners, we present a novel model for a sustained institutional presence, both with collaboration across UNC departments and with the presence of a senior surgical resident to provide continuity in research, education, and clinical care.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the North Carolina Jaycee Burn Center at the University of North Carolina; the University of North Carolina Center for AIDS Research Developmental Award (P30 AI50410); and by the National Institutes of Health Office of the Director, Fogarty International Center, Office of AIDS Research, National Cancer Center, National Eye Institute, National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institute of Dental & Craniofacial Research, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Health, and National Institutes of Health Office of Women’s Health and Research through the International Clinical Research Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988). The authors are particularly grateful to Anthony Meyer, MD, PhD, Chairman of the University of North Carolina Department of Surgery for his leadership and support of our work in Malawi.

Contributor Information

Javeria S. Qureshi, Email: jsquresh@gmail.com, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA

Jonathan Samuel, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA.

Clara Lee, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA.

Bruce Cairns, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA.

Carol Shores, Department of Otolaryngology/Head and Neck Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA.

Anthony G. Charles, Email: anthchar@med.unc.edu, Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4001 Burnett-Womack Bldg CB #7050, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599-7050, USA

References

- 1.Garrett L. The challenge of global health. Foreign Aff. 2007;86:14–38. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farmer PE, Kim JY. Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg. 2008;32:533–536. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivers LC, Garfein ES, Augustin J, et al. Increasing access to surgical services for the poor in rural Haiti. World J Surg. 2008;32:537–542. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9527-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Debas H, Gosselin R, McCord C, et al. Surgery. In: Jamison D, editor. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. pp. 1245–1259. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozgediz D, Hsia R, Weiser T, et al. Population health metrics for surgery: effective coverage of surgical services in low-income and middle-income countries. World J Surg. 2009;33:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9799-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daar AS, Singer PA, Persad DL, et al. Grand challenges in chronic non-communicable diseases. Nature. 2007;450:494–496. doi: 10.1038/450494a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. World health report 2006: Working together for health. Geneva: 2009. [Accessed 25 July 2009]. http://www.who.int/whr/2006/en/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pereira C, Cumbi A, Malalane R, et al. Meeting the need for emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: work performance and histories of medical doctors and assistant medical officers trained for surgery. BJOG. 2007;114:1530–1533. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacGowan WA. Surgical manpower worldwide. Bull Am Coll Surg. 1987;72:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Central Intelligence Agency; Washington DC: [Accessed 20 June 2010]. http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mi.html. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Central Intelligence Agency; Washington DC: [Accessed 15 Dec 2009]. http://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/mi.html. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown D. The need to be there. Carolina Alumni Rev. 2005;94(1):18–29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavy C, Tindall A, Steinlechner C, et al. Surgery in Malawi—a national survey of activity in rural and urban hospitals. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:722–724. doi: 10.1308/003588407X209329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jayaraman S, Ayzengart AL, Goetz LH, et al. Global health in general surgery residency. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization; Geneva: [Accessed 20 June 2010]. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/2004_report_update/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. Verbal autopsy standards: ascertaining and attributing cause of death. Geneva: [Accessed 20 June 2010]. http://www.who.int/whosis/mort/verbalautopsystandards/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozgediz D, Roayaie K, Wang J. Surgery and global health: the perspective of UCSF residents on training, research and service. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2006;91(5):26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]