Abstract

LYVE-1+ corneal lymphatics contribute to drainage and immunity. LYVE-1 is widely accepted as the most reliable lymphatic marker because of its continuous expression in lymphatic endothelium. LYVE-1 expression in corneal lymphatics has not been examined. In this study, we report intact CD31+ corneal lymphatic capillary endothelial cells that do not express LYVE-1. The number of LYVE-1− gaps initially increased until 8 wk of age but was significantly reduced in aged mice. C57BL/6 mice showed a notably higher number of the LYVE-1−/CD31+ lymphatic regions than BALB/c mice, which suggests a genetic predisposition for this histological feature. The LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps expressed podoplanin and VE-cadherin but not αSMA or FOXC2. Interestingly, the number of LYVE-1− gaps in FGF-2, but not VEGF-A, implanted corneas was significantly lower than in untreated corneas. Over 70% of the CD45+ leukocytes were found in the proximity of the LYVE-1− gaps. Using a novel in vivo imaging technique for visualization of leukocyte migration into and out of corneal stroma, we showed reentry of extravasated leukocytes from angiogenic vessels into newly grown corneal lymphatics. This process was inhibited by VE-cadherin blockade. To date, existence of lymphatic valves in cornea is unknown. Electron microscopy showed overlapping lymphatic endothelial ends, reminiscent of microvalves in corneal lymphatics. This work introduces a novel corneal endothelial lymphatic phenotype that lacks LYVE-1. LYVE-1− lymphatic endothelium could serve as microvalves, supporting unidirectional flow, as well as immunological hot spots that facilitate reentry of stromal macropahges.—Nakao, S., Zandi, S., Faez, S., Kohno, R., Hafezi-Moghadam, A. Discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in corneal limbal lymphatics: dual function as microvalves and immunological hot spots.

Keywords: lymphangiogenesis, VE-cadherin, imaging, leukocyte recruitment

In higher vertebrates, most tissues contain lymphatic vessels, except for avascular tissues, such as cornea, epidermis, and cartilage, and some vascularized tissues, such as brain and retina (1). The lymphatic system drains protein-rich interstitial fluids and immune cells (1). Recently, we reported the first physiological occurrence of lymphatic vessels in normal avascular mouse corneas (2). We found considerable diversity in constitutive lymphatic phenotype among mice of different genetic background (2). Corneal lymphatics are functional, as they resorb protein-rich fluids in dogs (3) and rabbits (4). In humans, conjunctival lymphatics remove excess interstitial fluids (5) and contribute to immunity, for instance, in corneal transplant rejection (6).

During the lymphatic development and remodeling, lymphatic capillaries are formed by sprouting and the collecting lymphatic vessels mature by deposition of the basement membrane, recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and development of lymphatic valves (7). Blind-ended lymphatic capillaries drain into larger collecting lymphatic vessels, which connect to the blood vessel system via the thoracic duct (1). Unlike blood vessels, the lymphatic capillaries form loose intercellular junctions and lack pericytes. Larger collecting lymphatic vessels have SMCs that actively support the fluid flow, and luminal valves that prevent backflow (1).

The hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1 is a specific marker for the lymphatic endothelium (8). In the skin, collecting lymphatics that have valves and are covered with SMCs show lower LYVE-1 expression, while lymphatic capillaries show high levels of LYVE-1 expression (7, 9). In contrast, corneal lymphatics lack SMCs, and there is no evidence of valves in them (10).

Two types of lymphatic valves are known: the classic macrovalves, found in collecting lymphatics, and the endothelial-level microvalves in the initial lymphatic capillaries (11). In lymphedema-distichiasis, a mutation in the forkhead transcription factor, FOXC2, causes dysfunctional lymphatics (12). FOXC2 is expressed in the developing lymphatics and in the collecting lymphatic valves of adults (13). Baluk et al. (14) reported that overlapping flaps at the borders of oak leaf-shaped endothelial cells of initial lymphatics lack junctions at the tip. These cells are anchored on the sides by discontinuous button-like junctions that differ from conventional, continuous, zipper-like junctions in collecting lymphatics and blood vessels (14). VE-cadherin is required for the maintenance of the button-like lymphatic endothelial junctions (14). However, whether corneal and conjunctival lymphatics have valves and whether microvalves exist at the level of lymphatic endothelial cells is unknown.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male (3 wk, 6–10 wk, or 6 mo old) C57BL6/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and BALB/cN mice from Taconic (Germantown, NY, USA). Male CD18−/− and PSGL-1−/− mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and bred in our animal facilities.

Corneal micropocket assay in mice

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Poly-HEMA pellets (0.3 μl, P3932; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) containing 200 ng VEGF-A (293-VE; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or 100 ng FGF-2 (3139-FB; R&D Systems) were prepared and implanted into the corneas. Cytokine pellets were positioned at ∼0.8–1.0 mm distance to the corneal limbus. After implantation, bacitracin ophthalmic ointment (E. Fougera & Co., Melville, NY, USA) was applied to each eye to prevent infection. On the indicated days after implantation, digital images of the corneal vessels were obtained using OpenLab 2.2.5 software (Improvision Inc., Lexington, MA, USA) with standardized illumination and contrast.

Whole-mount immunofluorescence

Eyes were enucleated and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at 4°C. For whole-mount preparation, the corneas were microsurgically exposed by removing other portions of the eye. Radial cuts were then made in the cornea. Tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) 3 times for 5 min and then placed in methanol for 20 min. Tissues were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-mouse CD31 mAb (5 μg/ml, 550274; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-mouse LYVE-1 Ab (4 μg/ml, 103-PA50AG; RELIATech GmbH, Braunschweig, Germany), anti-mouse podoplanin Ab (5 μg/ml, 11–033; AngioBio, Del Mar, CA, USA), anti-mouse CD45 mAb (5 μg/ml, 554875; BD Pharmingen), anti-mouse F4/80 mAb (10 μg/ml, MCA497R; Serotec, Kidlington, UK), anti-mouse FOXC2 Ab (10 μg/ml, ab5060; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), anti-mouse VEGFR-2 Ab (20 μg/ml, AF-644; R&D), anti-αSMA mAb (10 μg/ml, A5228; Sigma), or anti-mouse VE-cadherin Ab (10 μg/ml, 14–1441-81; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) diluted in PBS containing 10% goat serum and 1% Triton X-100. Tissues were washed 4 times for 20 min in PBS, followed by incubation with Alexa Fluor488 goat anti-rat IgG (20 μg/ml, A11006; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), Alexa Fluor488 goat anti-mouse IgG (20 μg/ml, A31619; Invitrogen), Alexa Fluor647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (20 μg/ml, A21244; Invitrogen), or Alexa Fluor594 goat anti-hamster IgG (20 μg/ml, A21113; Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. Corneal flatmounts were prepared on glass slides using a mounting medium (TA-030-FM, Mountant Permafluor; Lab Vison Corp., Fremont, CA, USA). The flatmounts were examined by fluorescence microscopy, and digital images were recorded using OpenLab 2.2.5 with standardized illumination and contrast.

Confocal microscopy

Confocal imaging was performed at 0.2-μm slice thickness (z stack), using a Leica microscope and a ×40 or ×100 oil-immersion objective (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Digital images were saved at 1024- × 1024-pixel resolution and imported into Image J software (U.S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) for 3-dimensional (3D) reconstruction. Red and green channels were consolidated using the XOR image calculator and further processed into the maximum image or 3D stack.

Transmission electron microscopy

Eyes were enucleated, and the corneas were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer with 0.08 M CaCl2 at 4°C and postfixed for 1.5 h in 2% aqueous OsO4, dehydrated in ethanol and water, and embedded in EPON. Ultrathin sections were cut from blocks and stained with saturated, aqueous uranyl acetate and Sato's lead stain. The specimens were observed with a Philips CM10 electron microscope (Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

Leukocyte transmigration rate assay

To visualize leukocyte transmigration rate and reentry into the corneal lymphatics, a new assay was developed. At 4 d after FGF-2 implantation, mice were anesthetized, and 500 μl AO (1 mg/ml) was injected intravenously. Starting 2 h after AO injection, mice were treated hourly with topical anti-VE-cadherin Ab (1 μg/μl, 16-1441; eBioscience) or isotype-matched IgG. To stain the blood vessels, animals were perfused with rhodamine-labeled concanavalin A lectin (ConA; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), 10 μg/ml in PBS (pH 7.4) at 2 and 6 h after AO injection. Briefly, under deep anesthesia, the chest cavity was opened, and a 24-gauge perfusion needle was placed into the aorta. Drainage was achieved by opening the right atrium. The animals were then perfused with 10 ml PBS to wash out blood cells in the vessels. After PBS perfusion, the animals were perfused with 5 ml rhodamine-labeled ConA and subsequently with 1 ml PBS to remove residual unbound ConA. Immediately after perfusion, the corneas were carefully removed, and flatmounts were prepared using a mounting medium (TA-030-FM, Mountant Permafluor; Lab Vision).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as means ± se, and values of n are as indicated. Student's t test was used for statistical comparison among the groups. Differences between the means were considered statistically significant at values of P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in normal corneal limbal lymphatics

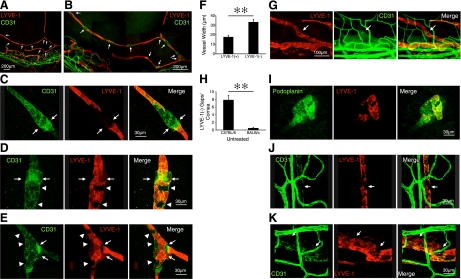

To examine lymphatic and blood vessel morphology, we performed immunostaining of the lymphatic endothelial marker LYVE-1 and blood vessel marker CD31 in untreated corneas of C57BL/6 mice. Surprisingly, corneal limbal lymphatics showed discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in CD31+ areas, with an average distance of 101.5 ± 7.6 μm (n=38 from 11 corneas) between them (Fig. 1A, B). Confocal imaging showed patchy occurrences of LYVE-1−CD31+ areas and remarkably distinct borders between these and the neighboring LYVE-1+CD31+ vessel regions (Fig. 1C–E).

Figure 1.

Discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in corneal lymphatics. A, B) Double staining of corneal flatmounts for vascular (CD31, green) and lymphatic endothelium (LYVE-1, red) in untreated C57BL/6. Arrows, discontinuous LYVE-1− and CD31+ lymphatic areas. C–E) Confocal images of various patterns of LYVE-1−CD31+ gaps in corneal flatmounts. Arrows, T junctions or hitch-like components of lymphatics. Arrowheads, patchy LYVE-1− cells. F) Quantification of the width of the LYVE-1− gaps and the neighboring LYVE-1+ vessel regions (n=9). G) Corneal flatmounts of untreated BALB/c mice (CD31, green; LYVE-1, red). Arrows indicate LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps. H) Quantitative analysis of the number of LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps in untreated corneas of C57BL/6 (n=12) and BALB/c mice (n=11). I) Confocal images of podoplanin expression (green) in LYVE-1− (red) gaps in corneal flatmounts. J, K) CD31 expression in LYVE-1− gaps in lymphatics of limbus (J) and conjunctiva (K). **P < 0.01.

The LYVE-1− areas were located mainly in bifurcations and in lymphatic vessels that were above the limbal blood vessel plexus. The LYVE-1− lymphatic sections showed significantly larger diameters than the preceding and following LYVE-1+ areas (P=0.0006; Fig. 1F). Since the genetic strain has a significant effect on the lymphatic phenotype (2), we also stained the corneas of BALB/c mice for LYVE-1 and CD31. Corneal limbal lymphatics of BALB/c mice also showed LYVE-1−CD31+ areas (Fig. 1G); however, their number was significantly lower than in C57BL/6 mice (P=0.00001; Fig. 1H).

To further characterize the lymphatic endothelial cells that cover the inner lumen of the LYVE-1− gaps, we performed immunostaining of the lymphatic marker podoplanin (15). LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps express podoplanin, indicating existence of lymphatic endothelial cells in the gaps (Fig. 1I). LYVE-1− gaps were also found in lymphatics of the limbal arcade and conjunctiva. However, those gaps were CD31− (Fig. 1J, K), which suggests that the LYVE-1− gaps in the limbus arcade and conjunctiva differ from those found in the corneal lymphatics.

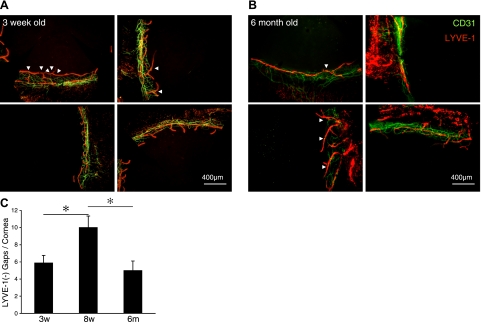

LYVE-1 expression in corneal limbal lymphatics during development and aging

To investigate the role of growth and aging in the development of the LYVE-1− gaps, we examined corneas at 3 different ages: 3 wk (young), 8 wk (mature), and 6 mo (aged) mice. Interestingly, the numbers of LYVE-1− gaps were significantly lower in 3-wk- or 6-mo-old mice than in 8-wk-old mice (P=0.04 and P=0.02, respectively), which suggests important changes to the lymphatics during initial physiological development and subsequent aging (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

LYVE-1 expression in corneal lymphatics during aging. A, B) Double staining of corneal flatmounts for vascular (CD31, green) and lymphatic endothelium (LYVE-1, red) in untreated 3-wk-old (A) and 6-mo-old (B) C57BL/6. C) Quantitative analysis of the number of LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps in untreated corneas of C57BL/6 mice (3 wk old, n=8; 8 wk old, n=5; 6 mo old, n=11). *P < 0.05.

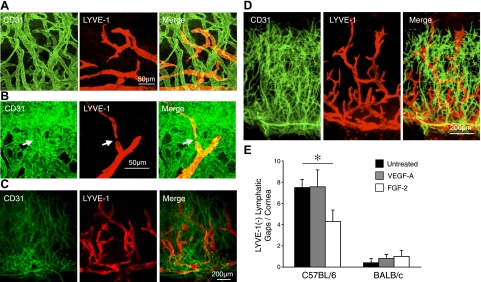

LYVE-1 expression in corneal lymphangiogenesis

To investigate whether the discontinuous LYVE-1 expression also occurs in GF-induced lymphangiogenesis, we examined LYVE-1 in VEGF-A- and FGF-2-stimulated corneas. VEGF-A implantation in C57BL/6 mice caused lymphangiogenic sproutings (Fig. 3A, B). Indeed, LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps also existed in lymphangiogenic vessels (Fig. 3B). However, the number of the LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps in VEGF-A-implanted corneas did not differ significantly from untreated C57BL/6 mice (P=0.96; Fig. 3B). To confirm that lymphangiogenic vessels do not form LYVE-1− gaps, we implanted VEGF-A in BALB/c mouse corneas, which have a larger lymphangiogenic response than C57BL/6 mouse corneas despite having fewer preexisting lymphatics (2). Despite apparent lymphangiogenic response in the VEGF-A-implanted eyes, no difference was found in the number of gaps between untreated and VEGF-A-implanted corneas in BALB/c mice (P=0.5; Fig. 3B, C).

Figure 3.

LYVE-1 expression in corneal lymphangiogenesis. Pellets containing VEGF-A (200 ng) were implanted into corneas of C57BL/6 and BALB/c mice. Double staining of corneal flatmounts for angiogenic (CD31, green) and lymphangiogenic (LYVE-1, red) endothelium. A, B) Confocal images of C57BL/6 corneas, 10 d after VEGF-A implantation. Arrows indicate LYVE-1− gaps in corneas with lymphangiogenesis. C) Day 6 in BALB/c mice after VEGF-A implantation. D) Day 6 in BALB/c mice after FGF-2 mplantation. E) Quantitation of the number of LYVE-1− gaps in corneas of untreated, VEGF-A or FGF-2-implanted eyes 6 d after pellet implantation (n=5–7). *P < 0.05.

To investigate the effect of another growth factor on LYVE-1− gap formation, we implanted FGF-2 and stained for LYVE-1 (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the number of LYVE-1− gaps in FGF-2-implanted corneas was significantly lower than in untreated corneas in C57BL/6 but not in BALB/c mice (P=0.04 and P=0.4; Fig. 3E). These data suggest that newly formed lymphangiogenic vessels do not form LYVE-1− gaps.

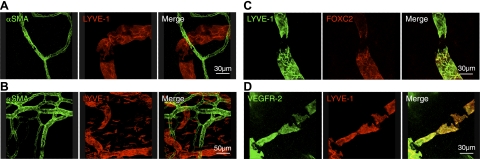

Lack of lymphatic valve characteristics in the cornea and conjunctiva

To examine whether LYVE-1− gaps are surrounded by SMCs, we performed immunostaining of αSMA, a specific marker of pericytes/SMCs that are found around lymphatic valves (7, 9). Confocal imaging did not show αSMA+ cells in the vicinity of LYVE-1− gaps or in the corneal and conjunctival lymphatics, although αSMA+ cells were present in blood vessels (Fig. 4A, B).

Figure 4.

Lack of valves in corneal lymphatics. A, B) Confocal images of double-stained corneal flatmounts for lymphatics (LYVE-1, red) and αSMA (green) in untreated eyes (A) and conjunctiva (B). C) Confocal images of double-stained corneal flatmounts for lymphatics (LYVE-1, green) and FOXC2 (red) in untreated cornea. D) Confocal images of double-stained corneal flatmounts for lymphatics (LYVE-1, red) and VEGFR-2 (green) in untreated cornea.

To examine, whether LYVE-1− gaps underlie lymphatic valves, we also examined the expression of FOXC2 and VEGFR-2 in LYVE-1− gaps. FOXC2 or VEGFR-2 were not expressed in LYVE-1− gaps (Fig. 4C, D), suggesting that corneal and conjunctival lymphatics lack the classical valve structures.

Microvalve characteristics in corneal and conjunctival lymphatics

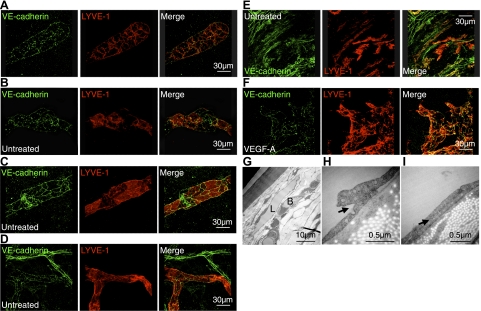

To investigate the existence of lymphatic microvalve characteristics on the endothelial level, we immunostained VE-cadherin in untreated corneas. Lymphatic round tips in untreated corneas showed discontinuous button-like staining with VE-cadherin (Fig. 5A). Some parts of corneal lymphatics were joined by continuous zipper-like structures. In particular, VE-cadherin expression around LYVE-1− gaps were zipper-like (Fig. 5B, C). Conjunctival lymphatics also showed discontinuous button-like staining, whereas conjunctival blood vessels showed continuous zipper-like VE-cadherin expression (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, some LYVE-1+ single cells in the conjunctiva expressed VE-cadherin (Fig. 5E). We further observed VE-cadherin expression in VEGF-A-induced lymphangiogenesis (Fig. 5F). These data indicate that unstimulated lymphatics and lymphangiogenic vessels in the cornea show signs of primitive lymphatic valve systems but no classic valves.

Figure 5.

Lymphatic endothelial junctions in cornea and conjunctiva. A–F) Confocal images of double-stained corneal flatmounts for LYVE-1 (red) and VE-cadherin (green) in untreated corneas (A–C), untreated conjunctiva (D, E), and VEGF-A-stimulated corneas (F; 200 ng, d 6) of C57BL/6 mice. G) Electron-microscopic images of untreated corneas. L, lymphatics; B, blood vessels. H, I) Arrows indicate overlapping valve-like lymphatic endothelial endings.

To further examine the phenotype of corneal lymphatics, we performed electron microscopy. Pericytes were not found around corneal lymphatics (Fig. 5G). However, remarkably, the lymphatic endothelium overlapped in untreated corneas, which suggests that the corneal lymphatics have microvalve-like structures (Fig. 5H, I).

Leukocyte colocalization around LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps

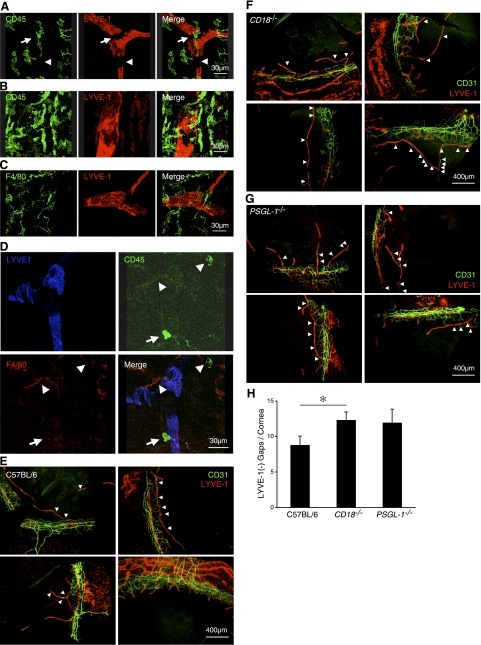

Inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α and -β, cause LYVE-1 degradation (16). Since TNF-α and -β are secreted by leukocytes, we hypothesized that leukocyte transmigration or adhesion might be associated with discontinuous LYVE-1 expression in the corneal lymphatics. To address this, we immunostained the corneal flatmounts with a mAb against the leukocyte marker, CD45. In untreated corneas, CD45+ leukocytes were observed around corneal and limbal lymphatic vessels; however, CD45+ cells were not found in all LYVE-1− gaps (Fig. 6A, B). Nineteen of 27 gaps (70.3%, n=6 corneas) showed CD45+ leukocytes, indicating a high association between leukocytes and the LYVE-1− gaps. We also observed macrophages in these gaps with F4/80 immunostaining (Fig. 6C). Seven of 11 CD45+ leukocytes on LYVE-1− gaps were F4/80+ (63.6%, n=3 corneas; Fig. 6D). To visualize the spatial relationship between the leukocytes and the lymphatics, we generated 3D compositions from confocal images. These 3D compositions show F4/80+ cells in Lyve-1− lymphatic gaps (Supplemental Video S1). Interestingly, none of the CD45+ cells in the lymphatic gaps were Gr-1+ (data not shown). These data indicate a high association of macrophages but not neutrophils with the LYVE-1− gaps. To investigate whether differences in leukocyte recruitment might affect LYVE-1 expression in lymphatics, we examined the number of LYVE-1− gaps in CD18−/− and PSGL-1−/− mice, known to have an altered immune response due to deficient leukocyte-endothelial interaction. Surprisingly, CD18−/− mice expressed significantly more LYVE-1− gaps (P=0.03) than control C57BL/6 mice, while the number of LYVE-1− gaps in PSGL-1−/− mice (P=0.2) did not differ from control (Fig. 6E–H).

Figure 6.

Leukocyte colocalization with LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps. A–C) Double staining of flatmounts for leukocytes (CD45, green; A, B) or macrophages (F4/80, green; C), and lymphatic endothelium (LYVE-1, red) of cornea (A, C) and limbus (B) in untreated C57BL/6 mice. D) Staining of corneal flatmounts for CD45 (green), F4/80 (red), and LYVE-1 (blue) in untreated C57BL/6 mice. Arrowhead, CD45+F4/80+ cells; arrows, CD45+F4/80− cells. E–G) CD31 and LYVE-1 double staining in untreated 8-wk-old C57BL/6 (E), CD18−/− (F), and PSGL-1−/− mice (G). H) Quantitative analysis of the number of LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps in untreated corneas of C57BL/6 (n=12), CD18−/− (n=13), and PSGL-1−/− mice (n=9). *P < 0.05.

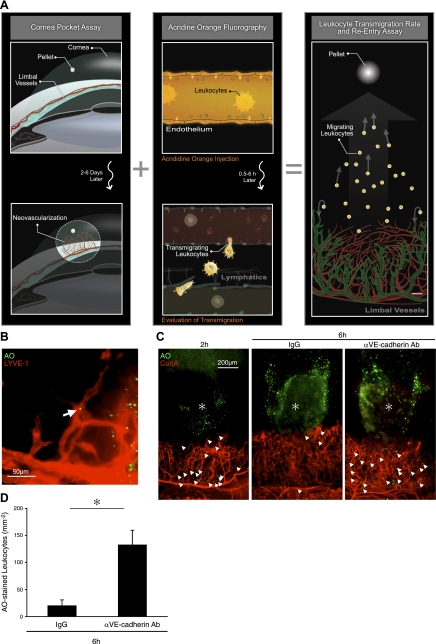

Novel imaging technique reveals VE-cadherin dependent leukocyte reentry into corneal lymphatics

To investigate reentry of transmigrated leukocytes into lymphatics, we developed a novel assay (Fig. 7A). By combining the growth factor-induced corneal angiogenesis with in vivo AO labeling of leukocytes, we achieved visualization of leukocyte extravasation from limbal and angiogenic blood vessels and their reentry into the corneal lymphatics. Systemically applied AO fluorescently stains the nuclei of the peripheral blood leukocytes and the vascular endothelium. While the concentration of AO in the intravascular leukocytes and the endothelial cells significantly diminished by 30 min after AO injection due to a washout effect, the transmigrated leukocytes in the corneal stroma retained their staining and could thus be quantified, and their reentry into the corneal lymphatics could be studied. Using this technique, we observed reentry of AO-laden transmigrated leukocytes from angiogenic vessels into the LYVE-1+ lymphangiogenic vessels, 4 d after FGF-2 implantation (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7.

VE-cadherin-dependent reentry of transmigrated leukocytes into lymphatics. A) Schematic of our new imaging technique for visualization of transmigrated leukocytes. B) AO+ leukocytes in FGF-2-induced lymphangiogenic vessels of C57BL/6 mice with LYVE-1 staining, 2 h after AO injection, 4 d after pellet implantation. C) AO+ leukocytes and Con A+ angiogenic vessels in FGF-2-implanted corneas, 2 and 6 h after AO injection, 4 d after pellet implantation. Topical anti-VE-cadherin Ab or IgG treatments, 2 h after AO injection. D) Quantitation of the number of AO+ leukocytes in angiogenic areas of FGF-2-implanted corneas, 6 h after AO injection. (n=3–4). *P < 0.05.

To investigate the role of lymphatic endothelial VE-cadherin for the reentry of these transmigrated leukocytes, we treated eyes at 2 h after AO injection with the anti-VE-cadherin mAb. We chose this time point for VE-cadherin inhibition, as by 2 h after AO injection, all AO + leukocytes were in the corneal stroma. In FGF-2-implanted corneas, at 2 h after AO injection, significant numbers of AO+ leukocytes were observed around angiogenic vessels. By 6 h after AO injection, only very few leukocytes were found around blood vessels, while most extravasated leukocytes had migrated and reached the pellet implantation site (Fig. 7C, D). Under these conditions, the extravasated leukocytes that reentered the lymphatics rapidly lost their AO dye, similarly to the stained leukocytes in the peripheral blood. In contrast to the IgG-treated controls, in anti-VE-cadherin mAb-treated corneas, a significant number of the AO+ leukocytes were found in the areas of vascular growth as well as around the pellets (Fig. 7C). Quantitative analysis showed that VE-cadherin blockade significantly inhibited the reentry of AO+ leukocytes into lymphatics (P=0.02; Fig. 7D).

DISCUSSION

The normal cornea and conjunctiva have preexisting lymphatics (2), the growth of which is induced in various pathologies (1, 2, 17, 18). The preexisting (3), as well as the newly growing, lymphatics (4) critically control the fluid balance in the eye. In the peripheral lymphatics, the contraction of skeletal muscles—for instance, during walking—supports the lymphatic flow (11), while valves prevent backflow. Analogously, in corneal lymphatics, the movements of the eyeball or blinking might drive the lymphatic flow. However, no known structures in ocular lympahtics support the unidirectionality of flow. This work introduces existence of endothelial level microvalves in corneal lymphatics and LYVE-1− areas that serve as immunological hot spots supporting reentry of tissue macrophages.

The larger collecting lymphatic vessels have classic macrovalves that are surrounded by SMCs. Conjunctival and corneal lymphatics in mice lack SMCs, which suggests absence of the classic macrovalves in these vessels. In the smaller lymphatic capillaries, endothelial level microvalves are thought to support the unidirectional fluid flow. Our measurements indicate 2–4 times smaller diameters of corneal lympahtics than the previously reported diameter of initial lymphatics (∼60 μm) in the mouse tail (19). This finding suggests that corneal and conjunctival lymphatics can be considered capillary-level lymphatics that have endothelial level microvalves. Our results, furthermore, show VE-cadherin expression in the corneal and conjunctival LYVE-1+ as well as LYVE-1− lymphatics, suggesting the existence of microvalve function in these vessels.

LYVE-1− gaps in the corneal lymphatics might result from the physical lengthening of the surface of the eyeball during growth. The subsequent proliferation and migration of lymphatic endothelium to achieve continuity might explain the LYVE-1− phenotype of the gaps, as LYVE-1 is regulated by the embryonic antigen, Prox-1 (20). Most LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps were found in the T junctions or hitches, which suggests that the extension of the lymphatics might underlie the down-regulation or disappearance of LYVE-1 expression. Interestingly, 8-mo-old mice have less LYVE-1− gaps than 6-wk-old mice, which might be due primarily to the fact that aged animals show fewer corneal lymphatics (21). Thus far, discontinuous LYVE-1 expression has not been found in lymphatic capillaries in any other tissue besides the cornea.

The surprisingly high association of leukocytes, and especially macrophages, with the LYVE-1− endothelium suggests a role for these cells in the formation of the gaps. TNF-α and -β, which down-regulate LYVE-1 expression in the lymphatic endothelium, are secreted by leukocytes (16). During inflammation or for the tissue homeostasis, leukocytes, including macrophages, infiltrate into the cornea (22, 23) and could reenter lymphatics to reach the lymph nodes. However, their reentry was previously unknown. The LYVE-1− gaps appear to be an entry port for corneal leukocytes to leave the corneal matrix and travel toward the lymph nodes, inspiring us to denote them immunological hot spots. The exit of leukocytes from the tissue into the lymphatics could function analogously to leukocyte extravasation into the matrix, which occurs through specific endothelial junctions (24). However, leukocyte-derived cytokines might not be the sole cause for the LYVE-1− gaps, as the number of the gaps does not increase in lymphangiogenic vessels, into which leukocytes transmigrate more frequently than under normal conditions (17). For instance, during lymphangiogenesis, growth factors such as FGF-2 might counter the cytokine-induced LYVE-1 down-regulation by TNF-α and -β.

Our results indicate endothelial-level microvalves in corneal lymphatics and a high association of leukocytes with LYVE-1− lymphatic gaps, which appear to be reentry ports for leukocytes into the lymphatic system. VE-cadherin critically mediates the leukocyte reentry into the lymphatics. Targeting of microvalves offers a novel approach in the treatment of inflammatory or edematous disorders.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. National Institutes of Health NIH grants AI050775 (A.H.-M.), an overseas Research Fellowship Award from Bausch & Lomb, a Fellowship Award from the Japan Eye Bank Association and Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society, and a Young Investigator Fellowship (to S.N. under the mentorship of A.H.-M.). The authors thank the Malaysian Palm Oil Board and the American Health Assistance Foundation. The authors thank Alexander Schering and Rebecca C. Garland for their help with the preparation of the manuscript and Dr. David Jackson and Dr. Takayuki Hattori for helpful suggestions. S.N. and A.H.-M. designed research and organized the experiments; S.N., S.Z., S.F., and R. K. performed research and analyzed data; S.N. and A.H.-M. wrote the paper. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1. Karpanen T., Alitalo K. (2008) Molecular biology and pathology of lymphangiogenesis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 3, 367–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nakao S., Maruyama K., Zandi S., Melhorn M. I., Taher M., Noda K., Nusayr E., Doetschman T., Hafezi-Moghadam A. (2010) Lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis: concurrence and/or dependence? Studies in inbred mouse strains. FASEB J. 24, 504–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Szeghy G., Zoltan T. O., Foldi M. (1963) The lymphatic system in the resorption of homologous serum from the cornea. Lancet 1, 832–833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Collin H. B. (1970) Lymphatic drainage of 131-I-albumin from the vascularized cornea. Invest. Ophthalmol. 9, 146–155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Singh D. (2003) Conjunctival lymphatic system. J. Cataract Refract. Surg. 29, 632–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen L., Hamrah P., Cursiefen C., Zhang Q., Pytowski B., Streilein J. W., Dana M. R. (2004) Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 mediates induction of corneal alloimmunity. Nat. Med. 10, 813–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Makinen T., Adams R. H., Bailey J., Lu Q., Ziemiecki A., Alitalo K., Klein R., Wilkinson G. A. (2005) PDZ interaction site in ephrinB2 is required for the remodeling of lymphatic vasculature. Genes Dev. 19, 397–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Banerji S., Ni J., Wang S. X., Clasper S., Su J., Tammi R., Jones M., Jackson D. G. (1999) LYVE-1, a new homologue of the CD44 glycoprotein, is a lymph-specific receptor for hyaluronan. J. Cell Biol. 144, 789–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tammela T., Saaristo A., Holopainen T., Lyytikka J., Kotronen A., Pitkonen M., Abo-Ramadan U., Yla-Herttuala S., Petrova T. V., Alitalo K. (2007) Therapeutic differentiation and maturation of lymphatic vessels after lymph node dissection and transplantation. Nat. Med. 13, 1458–1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Albuquerque R. J., Hayashi T., Cho W. G., Kleinman M. E., Dridi S., Takeda A., Baffi J. Z., Yamada K., Kaneko H., Green M. G., Chappell J., Wilting J., Weich H. A., Yamagami S., Amano S., Mizuki N., Alexander J. S., Peterson M. L., Brekken R. A., Hirashima M., Capoor S., Usui T., Ambati B. K., Ambati J. (2009) Alternatively spliced vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 is an essential endogenous inhibitor of lymphatic vessel growth. Nat. Med. 15, 1023–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trzewik J., Mallipattu S. K., Artmann G. M., Delano F. A., Schmid-Schonbein G. W. (2001) Evidence for a second valve system in lymphatics: endothelial microvalves. FASEB J. 15, 1711–1717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Fang J., Dagenais S. L., Erickson R. P., Arlt M. F., Glynn M. W., Gorski J. L., Seaver L. H., Glover T. W. (2000) Mutations in FOXC2 (MFH-1), a forkhead family transcription factor, are responsible for the hereditary lymphedema-distichiasis syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 67, 1382–1388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petrova T. V., Karpanen T., Norrmen C., Mellor R., Tamakoshi T., Finegold D., Ferrell R., Kerjaschki D., Mortimer P., Yla-Herttuala S., Miura N., Alitalo K. (2004) Defective valves and abnormal mural cell recruitment underlie lymphatic vascular failure in lymphedema distichiasis. Nat. Med. 10, 974–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baluk P., Fuxe J., Hashizume H., Romano T., Lashnits E., Butz S., Vestweber D., Corada M., Molendini C., Dejana E., McDonald D. M. (2007) Functionally specialized junctions between endothelial cells of lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 204, 2349–2362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Breiteneder-Geleff S., Soleiman A., Kowalski H., Horvat R., Amann G., Kriehuber E., Diem K., Weninger W., Tschachler E., Alitalo K., Kerjaschki D. (1999) Angiosarcomas express mixed endothelial phenotypes of blood and lymphatic capillaries: podoplanin as a specific marker for lymphatic endothelium. Am. J. Pathol. 154, 385–394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson L. A., Prevo R., Clasper S., Jackson D. G. (2007) Inflammation-induced uptake and degradation of the lymphatic endothelial hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33671–33680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Watari K., Nakao S., Fotovati A., Basaki Y., Hosoi F., Bereczky B., Higuchi R., Miyamoto T., Kuwano M., Ono M. (2008) Role of macrophages in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis: Enhanced production of vascular endothelial growth factor C and D through NF-kappaB activation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 377, 826–831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakao S., Zandi S., Hata Y., Kawahara S., Arita R., Schering A., Sun D., Melhorn M. I., Ito Y., Lara-Castillo N., Ishibashi T., Hafezi-Moghadam A. (2011) Blood vessel endothelial VEGFR-2 delays lymphangiogenesis: an endogenous trapping mechanism links lymph- and angiogenesis. Blood 117, 1081–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hagendoorn J., Padera T. P., Kashiwagi S., Isaka N., Noda F., Lin M. I., Huang P. L., Sessa W. C., Fukumura D., Jain R. K. (2004) Endothelial nitric oxide synthase regulates microlymphatic flow via collecting lymphatics. Circ. Res. 95, 204–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wigle J. T., Harvey N., Detmar M., Lagutina I., Grosveld G., Gunn M. D., Jackson D. G., Oliver G. (2002) An essential role for Prox1 in the induction of the lymphatic endothelial cell phenotype. EMBO J. 21, 1505–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hos D., Bachmann B., Bock F., Onderka J., Cursiefen C. (2008) Age-related changes in murine limbal lymphatic vessels and corneal lymphangiogenesis. Exp. Eye Res. 87, 427–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nakao S., Kuwano T., Tsutsumi-Miyahara C., Ueda S., Kimura Y. N., Hamano S., Sonoda K. H., Saijo Y., Nukiwa T., Strieter R. M., Ishibashi T., Kuwano M., Ono M. (2005) Infiltration of COX-2-expressing macrophages is a prerequisite for IL-1 beta-induced neovascularization and tumor growth. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2979–2991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakao S., Hata Y., Miura M., Noda K., Kimura Y. N., Kawahara S., Kita T., Hisatomi T., Nakazawa T., Jin Y., Dana M. R., Kuwano M., Ono M., Ishibashi T., Hafezi-Moghadam A. (2007) Dexamethasone inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced corneal neovascularization: role of nuclear factor-kappaB-activated stromal cells in inflammatory angiogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 1058–1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schenkel A. R., Mamdouh Z., Muller W. A. (2004) Locomotion of monocytes on endothelium is a critical step during extravasation. Nat. Immunol. 5, 393–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.