ABSTRACT

Both the systemic and the uteroplacental renin-angiotensin system (RAS) display dramatic changes during pregnancy. However, whether gestational protein insufficiency affects the expressions of RAS in the placenta remains unknown. In this study, we hypothesized that the expression of Ace2 in the placental labyrinth was reduced by maternal protein restriction. Pregnant Sprague-Dawley rats were fed a normal diet or a low-protein diet (LP) from Day 1 of pregnancy until they were killed at Day 14 or Day 18. The labyrinth zone (LZ) of the placenta was then dissected and snap frozen for expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR of Ace, Ace2, Agtr1a, Agtr1b, and Agtr2. Formalin-fixed placentas were used for immunohistochemical analysis on ACE and ACE2 proteins. The findings include 1) the expression of Ace2 in rat LZ was reduced by maternal protein restriction in late pregnancy; 2) ACE protein was mainly present in syncytiotrophoblasts, whereas ACE2 protein was found predominantly in fetal mesenchymal tissue and fetal capillaries; 3) Agtr1a was predominant in the rat LZ, and its mRNA levels, but not protein levels, were reduced by LP; 4) expressions of Ace, Ace2, and Agtr1a in the rat LZ and their response to LP occurred in a gender-dependent manner. These results may indicate that a reduced expression of Ace2 and perhaps an associated reduction in angiotensin (1–7) production in the placenta by maternal protein restriction may be responsible for fetal growth restriction and associated programming of adulthood hypertension.

Keywords: angiotensin I-converting enzyme, labyrinth zone, maternal protein restriction, placenta, pregnancy, rodents, (guinea pigs, mice, rats, voles)

Maternal protein restriction reduces expression of Ace2 and alters expression of Ace and Agtr1 in the rat labyrinth in a gender-specific manner, which may be responsible for the placental programming on adulthood hypertension.

INTRODUCTION

The renin-angiotensin system (RAS) plays a critical role in regulating sodium and water homeostasis. Recently, the renal RAS has been implicated in fetal programming of hypertension induced by hormonal treatments [1, 2], dietary manipulations including maternal global nutrient restriction [3] and protein restriction [4], and uteroplacental insufficiency [5] during gestation. The RAS displays remarkable changes, such as an increased expression of its components in multiple organs, including the uterus and placenta [6–9], during pregnancy. It has been reported that the RAS in the placenta is sensitive to maternal hypoxic stress [10] and placental insufficiency [11].

Additionally, the RAS plays an important role in placental development and regulation of uteroplacental blood circulation. Further, pregnancy is coincident with a progressive increase in RAS components [6]. In early pregnancy, angiotensin II, a product of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), promotes decidualization and rapid trophoblast proliferation, mainly by binding to its receptor AGTR1 [8, 12, 13]. In mid and late pregnancy in the rat, the placental labyrinth zone (LZ), the main compartment for maternal-fetal hemotrophic exchange [14], undergoes rapid and intense angiogenesis. This results in expanded maternal blood space and progressive fetal capillary development, which may be one of the mechanisms responsible for the remarkable increase in placental efficiency during late pregnancy [14, 15]. The elevated expressions of ACE, ACE2, and angiotensin (1–7) in normal mid and late pregnancy [6, 9, 13] and the presence of functional AGTR1 in the placenta [12, 13, 16–19] indicate that the RAS is involved in this complicated process in late pregnancy. Angiotensin (1–7), a product of ACE II (ACE2), a potent endogenous vasodilator, is elevated with the advancement of pregnancy due to enhanced ACE2 expression and activity [6, 9], which correlate with elevated placental-fetal blood flow and rapid fetal growth, especially during mid and late pregnancy.

The dysregulation of the RAS in the placenta is associated with preeclampsia and other pathophysiological conditions during pregnancy [7, 8, 20]. Decreased expression of AGTR1 in the placenta causes fetal intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) [17], whereas upregulation of AGTR1 is seen in the preeclamptic placenta [16]. Angiotensin II reduces amino acid transport in human placental villi [18] and trophoblast invasion [19] and possibly suppresses the expression of Ace2 [21, 22]. In addition, angiotensinogen, the substrate for production of angiotensin I and other angiotensin peptides, is not produced in the murine placenta [10], but transported from the maternal circulation [10, 23]. Therefore, both systemic and local regulations of RAS function occur in the placenta.

It has been established that offspring from dams with maternal protein restriction during gestation develop hypertension and cardiovascular diseases in adulthood in a gender- and time-dependent manner, with an earlier onset and more severe hypertension in males compared to females [4, 24–29]. Pregnant rats subjected to a low-protein diet (LP) have also been widely used in the study of metabolic programming [30]. Interestingly, the metabolic syndrome caused by maternal protein restriction can be related to the gender of offspring [30–32]. However, the gender-specific effects of maternal protein restriction and other maternal insults on fetal growth and placental efficiency have received little attention [33].

In this study, we hypothesized that the expression of Ace2 in the placental labyrinth was reduced by maternal protein restriction. The objectives were to study the gender-specific effects of maternal protein restriction on the expression of Ace, Ace2, Agtr1a, Agtr1b, and Agtr2 in LZ and to immunohistochemically analyze ACE and ACE2 proteins in rat placental LZ.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Experimental Design

All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Medical Branch and were in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health's Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). Virgin female Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan Sprague Dawley) weighing between 175 and 225 g were mated with male Sprague-Dawley rats; conception was confirmed by the observation of a vaginal copulation plug or the presence of sperm in the vaginal flush, and this day was determined to be Day 1 of pregnancy. Pregnant rats were randomly divided into two dietary groups, housed individually and fed an isocaloric control diet (CT, 20% Protein Diet, Cat. TD.91352; Harlan Teklad) or LP (6% Protein Diet, Cat. TD.90016; Harlan Teklad) until they were killed on Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (n = 10 rats/diet/day of pregnancy). The LZ and the junctional zone (JZ) were dissected as described by Ain et al. [34]. The LZ and JZ were then snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

DNA Extraction from Fetal Extraembryonic Membrane and Sex Determination

DNA was extracted and fetal sex determined as described by Gao et al. [35]. Briefly, genomic DNA was extracted from frozen fetal membranes in our first study and, in the second, with a Qiagen DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Cat. 69504, Qiagen), and all procedures were followed by using the manufacturers' instructions. The animals' sex was determined in PCR reactions by assessing the presence or absence of the Sry gene in genomic DNA.

RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

Total RNA from frozen LZ (n = 6 tissues/diet/gender/day of pregnancy) was extracted by using a Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Cat. 74104, Qiagen) and digested with RNA-free DNase I (Cat. 79254, Qiagen), followed by cleanup procedures, completed by following the manufacturer's instructions. Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA by RT in a total volume of 20 μl by using a MyCycler Thermal Cycler (Cat. 170-9703, Bio-Rad) under the following conditions: One cycle at 28°C for 15 min, 42°C for 50 min, and 95°C for 5 min.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR detection was performed on a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Cat. 184-5096, Bio-Rad). TaqMan gene expression assays for rat Ace (Rn00561094_m1), Ace2 (Rn01416289_m1), Agtr1a (Rn01435427_m1), Agtr1b (Rn02132799_s1), Agtr2 (Rn00560677_s1), and Gapdh (Rn01775763_g1) and supermix reagents were from Applied Biosystems. The reaction reagent mixture was incubated at 50°C for 2 min, heated to 95°C for 10 min, and cycled according to the following parameters: 95°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min for a total of 40 cycles. Gapdh served as an internal control to standardize the amount of sample RNA added to a reaction. Data were expressed as the ratio of the DNA amplification amount of Gapdh against that of target genes to avoid the error from the differences in tissue weight, processing, and loading. The relative amount of every sample was calculated by use of the threshold cycle (CT) Gapdh/CT target gene.

Western Blotting

The preparation of tissue lysates from rat LZ was described by Gao et al. [35]. Rat LZs (n = 6 LZs/diet/gender/day of pregnancy) were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 0.1 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid, 1 mM PMSF, 1.4 μl of beta-mercaptoethanol, and one mini-tablet of protease inhibitor cocktail per 10 ml) with polytran at 15 000 rpm for 30 sec. After centrifugation of the homogenate at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, the supernatant fraction was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until analyzed by Western blotting. Protein concentration was determined by using a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Cat. 23225; Pierce Biotechnology).

Aliquots of 20 μg protein were added with 4× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Cat. NP0007; Invitrogen) and subjected to electrophoresis with NUPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Gel (Cat. NP0006; Invitrogen) and MOPS SDS running buffer (Cat. NP0001; Invitrogen). Briefly, the separated proteins in SDS-PAGE were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 4°C overnight. After blocking in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST; wt/vol; 20 mM Tris, 150 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.5, 0.05% Tween-20 [vol/vol]), a rabbit anti-ACE polyclonal immunoglobulin G (IgG; Cat. PT344R; Panora Biotech) at 1:1000 dilution in 2% nonfat milk in TBST (wt/vol) or a goat anti-AGTR1 polyclonal IgG (Cat. sc-31181; Santa Cruz) at 1:200 dilution in 2% nonfat milk in TBST was added to nitrocellulose membrane and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing, the blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cat. 1030-06; SouthernBiotech) or HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Cat. 6420-05; SouthernBiotech) at 1:5000 dilution in 2% nonfat milk in TBST at room temperature for 1 h. Proteins in blots were visualized with Pierce enhanced chemiluminescence detection (Cat. 32209; Thermo Scientific) and Blue Lite Autorad film (Cat. F9024; BioExpress) according to the manufacturers' recommendations. Beta-actin (ACTB) was used as an internal control for Western blotting in this study. Primary antibody, mouse monoclonal antibody for ACTB (Cat. 3700; Cell Signaling), and secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Cat. 1030-05; Southern Biotech) were used at 1:10 000 and 1:5000 dilution in 2% nonfat milk in TBST, respectively. Visualization of proteins in blots was the same as mentioned above. Blots were incubated with stripping buffer (Cat. 46430; Thermo Scientific) at room temperature for 15 min, followed by blocking in 5% nonfat milk in TBST for 1 h. The blots were incubated with a rabbit anti-ACE2 polyclonal IgG (Cat. ab87436; Abcam) at 1:1000 dilution in 2% nonfat milk in TBST at room temperature for 2 h. The following procedures were the same as those for ACE analysis.

The signals in films representing the contents of the target proteins ACE, ACE2, AGTR1, and the internal control protein ACTB were densitometrically quantified by using Fluorchem 8000 software (Cell Biosciences). The relative amount of target protein was calculated by the ratio of total densitometric value of target protein to that of ACTB in each rat LZ analyzed by Western blotting.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin sections (5 μm; n = 5 sections/diet/gender/day of pregnancy) were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated to water through a graded alcohol series (100%, 95%, and 70%, vol/vol). Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the sections in citrate buffer (0.01 M, pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was destroyed by washing the sections in 1% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min. Sections were blocked in normal goat serum provided in a Vectastain Elite ABC kit (Cat. PK-6101; Vector Laboratories). Sections were then incubated with a rabbit anti-ACE1 polyclonal IgG (Cat. PT344R; Panora Biotech) and rabbit anti-ACE2 polyclonal IgG (Cat. ab87436; Abcam), respectively, at 1 μg/ml final concentrations in 0.1% BSA (Cat. A7906; Sigma-Aldrich) in 1× PBS (wt/vol). Purified, nonrelevant rabbit IgG (Cat. I5006; Sigma-Aldrich) at the same concentration as above was used as a negative control. Immunoreactive protein was visualized in sections by using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit according to kit instructions and 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Cat. D5637; Sigma-Aldrich) as the color substrate. Sections were counterstained with Gill hematoxylin before cover slips were affixed. The slides were examined under a microscope (Nikon Instruments). Images of representative fields were recorded using a Nikon Eclipse 1000 photomicroscope (Nikon Instruments) fitted with a Nikon DXM1200 digital camera.

Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data were subjected to least-squares ANOVA by using the general linear models procedures of Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS Institute). Data on fetal-placental weight and gene expression were analyzed for effects of day of pregnancy, diet treatment, gender of placenta, and their interaction. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered significant, whereas a P value of 0.05–0.10 was considered to represent a trend toward significance. Data in tissue weights are presented as mean with SEM, and data in gene expression are presented as least-squares means with overall SEMs.

RESULTS

Fetal Growth Was Impaired by Maternal Protein Restriction

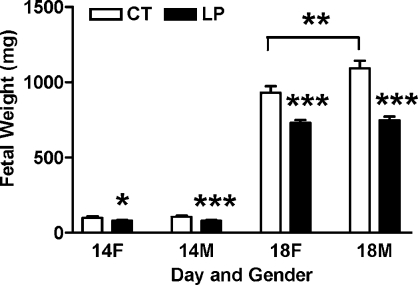

The fetal weights in the CT and LP groups are summarized in Figure 1. Both female and male fetal weights were lower (P < 0.05) in the LP groups at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy compared to those in the control groups. At Day 14 of pregnancy, female and male fetal weights in LP groups accounted for 81.6% and 74.7% of those in control groups, respectively (P < 0.05, P < 0.001). At Day 18 of pregnancy, female and male fetal weights in LP groups accounted for 78.4% and 68.5% of those in control groups, respectively (P < 0.001). In control groups, male fetal weights were similar to female fetal weights at Day 14 of pregnancy, and heavier than female fetal weights (P < 0.01) at Day 18 of pregnancy. In LP groups, male and female fetal weights were similar at both Day 14 and Day 18 of pregnancy.

FIG. 1.

Fetal weights in rats fed with the normal diet (CT) and LP at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Effects of Maternal Protein Restriction on the mRNA Levels of Ace, Ace2, and Agtr1a in the Rat LZ

The mRNA levels of Ace in the LZ were increased by 14.8-fold from Day 14 to Day 18 of pregnancy (P < 0.0001), but were unaffected by gender and diet (Fig. 2A). In the LP groups, the mRNA levels of Ace2 were decreased by 1.7-fold (P < 0.05) and 1.5-fold (P < 0.05) in the male LZ at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy, respectively. Notably, the mRNA levels of Ace2 in the LZ were very low, but detectable by quantitative real-time PCR at Day 14 of pregnancy (Fig. 2B). The mRNA levels of Agtr1a (angiotensin II receptor, type 1a) were decreased by 1.4-fold (P < 0.05) in the male LZ at Day 18 of pregnancy in the LP group, but not changed in the female LZ; in control groups, the mRNA levels of Agtr1a were significantly higher in the male LZ compared to those in the female LZ (Fig. 2C). The expressions of Agtr1b (angiotensin II receptor, type 1b) and Agtr2 (angiotensin II receptor, type 2) in the rat LZ were barely detectable by quantitative real-time PCR (data not shown), and thus, Agtr1a was predominant in the rat LZ.

FIG. 2.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of Ace (A), Ace2 (B), and Agtr1a (C) in the rat LZ. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as relative units of mRNA standardized against Gapdh (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Effects of Maternal Protein Restriction on ACE, ACE2, and AGTR1 Proteins in the Rat LZ

At Day 14 of pregnancy, the abundance of ACE protein was decreased by LP in both the female and male LZs (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, respectively) and accounted for 74.1% and 41.4% of that in the female and male LZs of CT rats. In control rats, ACE protein levels in the male LZ were 1.5-fold higher compared to those in the female LZ (P < 0.05). At Day 18 of pregnancy, ACE protein levels were not changed by LP; ACE protein levels in the male LZ were about one half of those in their female counterparts (P < 0.001) in both the CT and LP groups (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Western blotting analysis of ACE protein in the rat LZ. A) ACE proteins shown in 150-kDa bands. F, female; M, male. B) Relative abundance of ACE protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of density of the ACE band to that of ACTB (n = 6). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

At Day 14 of pregnancy, the ACE2 protein levels in the male LZ were reduced (P < 0.001) by LP to 33.8% of those in the CT group, whereas they were not changed by LP in the female LZ; in the CT group, ACE protein levels in the male LZ were 1.8-fold higher compared to those in the female LZ (P < 0.05). At Day 18 of pregnancy, the abundance of ACE2 protein was decreased by LP in both female and male LZs (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, respectively) and accounted for 27.5% and 34.8% of that in female and male LZs in the CT group, respectively (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Western blotting analysis of ACE2 protein in the rat LZ. A) ACE2 proteins shown in 90-kDa bands. F, female; M, male. B) Relative abundance of ACE2 protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of density of ACE bands to those of ACTB. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

At Day 14 of pregnancy, the abundance of AGTR1 was not affected by diet or gender. At Day 18 of pregnancy, the abundance of AGTR1 protein was increased by 1.7-fold in the female LZ by LP (P < 0.01), but not changed in the male LZ; in the CT group, AGTR1 protein levels in the male LZ were 1.3-fold higher compared to those in the female LZ (P < 0.05) (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Western blotting analysis of AGTR1 protein in the rat LZ. A) AGTR1 proteins shown in 27-kDa bands. F, female; M, male. B) Relative abundance of AGTR1 protein. The error bar represents the mean ± SEM expressed as the ratio of density of ACE bands to those of ACTB. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

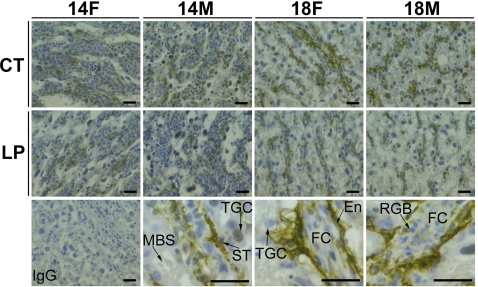

Immunohistochemical Analysis of ACE and ACE2 in the Rat LZ

The immunoreactive ACE protein was detectable in LZ at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy. At Day 14 of pregnancy, immunoreactive ACE protein was seen more uniformly in the syncytiotrophoblast and sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells (a type of trophoblast giant cell localized in maternal blood space). The intensity of staining for ACE is relatively higher in the CT group compared to the LP group. At Day 18 of pregnancy, immunoactive ACE protein was abundant in syncytiotrophoblast and endothelial cells in fetal capillaries. The staining of ACE protein was also present in the nuclei of some trophoblast giant cells (Fig. 6). Moreover, the intensity of staining was higher in the LZ area close to the JZ, and the intensity of staining decreased progressively toward the umbilical site (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Immunohistochemical analysis of ACE protein in the rat LZs. A representative negative control for immunostaining (IgG from nonrelevant rabbit) and three representative images for immunostaining in trophoblast cell and fetal capillary in a female LZ at Day 18 of pregnancy (shown in high magnification) were present in the bottom row in the micrograph. F, female; M, male; En, endothelial cell; FC, fetal capillary; MBS, maternal blood space; RBC, red blood cell; ST, syncytiotrophoblasts; TGC, trophoblast giant cell. Bar = 10 μm.

The immunoreactive ACE2 was detectable in the LZ at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy. Unlike ACE, immunoreactive ACE2 was most abundant in the mesenchymal tissues surrounded by syncytiotrophoblast cells and fetal capillaries and including endothelial cells. The staining of ACE protein was also present in the nuclei of some sinusoidal trophoblast giant cells (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Immunohistochemical analysis of ACE2 protein in the rat LZs. A representative negative control for immunostaining (IgG from nonrelevant rabbit) and three representative images for immunostaining in trophoblast cells and fetal capillary in a female LZ at Day 18 of pregnancy (shown in high magnification) were present in the bottom row in the micrograph. F, female; M, male; En, endothelial cell; FC, fetal capillary; MBS, maternal blood space; RBC, red blood cell; ST, syncytiotrophoblast; TGC, trophoblast giant cell. Bar = 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to report the effects of maternal protein restriction on gene expressions of RAS components in the rat placental LZ. We show that maternal protein restriction reduced the expression of Ace2 in the rat LZ in late pregnancy, and altered expressions of Ace, Ace2, and Agtr1a in the rat LZ in a gender-specific manner. This study suggests a correlation between protein restriction, reduced Ace2 expression in LZ, and impaired fetal growth, and indicate a role for placental RAS in fetal growth restriction and associated programming on adulthood hypertension.

We report for the first time that ACE proteins are very abundant in the syncytiotrophoblasts and fetal vascular capillaries. Our findings of the localization of ACE2 protein in the rat LZ are consistent with those in another study by Neves et al. [13]. In rodent placenta, syncytiotrophoblasts and cytotrophoblasts form trilaminar epithelia out of vascular fetal mesenchyme, and the syncytiotrophoblast is bathed in maternal blood space [36]. The colocalization of ACE and ACE2 and the presence of AGTR1 [16] in fetal vascular tissues indicate that the RAS regulates fetal blood flow in an autocrine manner, similar to that in lungs, heart, and kidneys [37]. The distribution of ACE and ACE2 in the neighboring cells, syncytiotrophoblast cells and vascular fetal mesenchymal cells, indicates that the relay of the two key enzymes in angiotensin (1–7) production may represent crosstalk in the maternal-fetal interface. The similarity in the distribution of ACE and ACE2 in human [38] and rodent placenta implies that the RAS is highly conserved and plays a critical role in this organ.

Maternal protein restriction decreased the expression of Ace2 in the rat LZ during late pregnancy. The reduced mRNA levels of Ace2 were seen in the male LZ at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy and in the female LZ at Day 18 of pregnancy. Strikingly, at Day 14 of pregnancy, the protein levels of ACE2 in the male LZ were reduced by 2.9-fold by LP; at Day 18 of pregnancy, protein levels of ACE2 were decreased by 3.6-fold and 2.9-fold by LP in the female and male LZs, respectively (Fig. 4). The LP-induced reduction in the expression of Ace2 in the male LZ occurs earlier compared to that in the female LZ, which is correlated with the more severe fetal growth retardation of male fetuses observed at Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (Fig. 1). Considering that the main activity of ACE2 is to convert angiotensin II to angiotensin (1–7) and the correlation between the expression of Ace2 and concentration of angiotensin (1–7) in the rat placenta in response to reduced uterine perfusion [13], it is reasonable to expect that angiotensin (1–7) production is reduced by LP in the male and female LZs. Ace2 expression and associated angiotensin (1–7) production in the main organs, including placenta, uterus, and kidney, are enhanced with the advancement of gestation [6]. A reduction in uterine perfusion can decrease the expression of Ace2 and concentration of angiotensin (1–7) in placenta [13] and thus cause IUGR in male fetuses and subsequent hypertension in male adult offspring [39]. Taken together, the altered expression of Ace2 and associated angiotensin (1–7) production in placenta may be susceptible to maternal insults in pregnancy and mediate the placental programming by these insults.

In addition to the reduction of angiotensin (1–7) in the rat LZ by maternal protein restriction, the accumulation of angiotensin II may contribute to the impaired placental sufficiency, especially in late pregnancy. We previously reported that placental sufficiency, represented as the ratio of fetal to placental weight, was reduced in both male and fetal placenta by LP in late pregnancy [35]. At Day 18 of pregnancy, the abundance of ACE proteins in both the male and female LZs was not changed by LP (Fig. 3), whereas the abundance of ACE2 proteins was decreased by LP (Fig. 4). These findings may indicate that more angiotensin II was accumulated locally in the LZ. The facts that angiotensin II reduces placental amino acid transport [18] and trophoblast invasion [8, 19] and that placental amino acid transport is decreased by maternal protein restriction [40, 41] support the notion that the elevated angiotensin II may favor vasoconstriction and contribute to the impaired blood flow and associated reduction in nutrient transport to the fetus in late pregnancy. Interestingly, the levels of AGTR1 protein were increased in females by LP at Day 18 (Fig. 5), although mRNA levels of Agtr1a were not changed by LP in the female LZ at Day 18 of pregnancy (Fig. 2C). The increased expression of Agtr1 in the female LZ may further exacerbate the vasoconstriction by angiotensin II. In addition, the accumulation of angiotensin II in the LZ in response to maternal protein restriction may suppress the expression of Ace2, as shown in myocytes and astrocytes [21, 22]. Thus, increased AGTR1 and reduced ACE2 together with elevated angiotensin II in response to maternal protein restriction could result in placental insufficiency.

The expressions of Ace and Agtr1a may be regulated at the posttranscriptional level. The pattern of changes in the mRNA levels and protein levels for these two genes did not match (Figs. 2–5); however, the underlying mechanisms are unknown. Recently, several studies have demonstrated that gene expression of RAS components is posttranscriptionally regulated by miRNAs [10, 42]. Upregulation of miRNAs mmu-mir-27a and 27b by maternal protein restriction reduces the ACE proteins in the brains of offspring. Similar regulation by miRNA also occurs for Agtr2 [42]. To date, it is unknown whether dietary manipulations alter the levels of miRNAs with in the placenta and whether the identified miRNAs in the brain are present in placenta and regulate the corresponding gene expressions.

The expressions of RAS in the LZ and their responses to maternal protein restriction are shown in both gender- and gestational day-specific manners. First, in control rats, at Day 14 of pregnancy, both mRNA and protein levels of Ace2 are higher in the male LZ compared to those in the female LZ. However, maternal protein restriction lowered ACE2 protein levels in the male LZ from Day 14 of pregnancy, which was earlier than in the female LZ. The comparable amount of ACE2 proteins in the female and male LZs in LP groups with similarity in fetal weights in female and male fetuses in midpregnancy may indicate a lesser role played by the RAS in fetal growth. In contrast, in late pregnancy, when Ace and Ace2 expression are greater in normal mid and late pregnancy [6, 9, 13], the alteration in the RAS may play a greater role in fetal growth. Second, in control rats, at Day 18 of pregnancy the mRNA levels of Agtr1a were higher in the male LZ compared to the female LZ, and LP reduced mRNA levels of Agtr1a in only the male LZ. In contrast, at Day 18 of pregnancy, protein levels of AGTR1 in the female LZ, but not in the male LZ, were increased by LP, whereas the protein levels of AGTR1 in the female and male LZs in LP groups were similar. Third, at Day 14 of pregnancy, protein levels of ACE were higher in the male LZ compared to the female LZ in the control group; at Day 18 of pregnancy, regardless of diet, protein levels of ACE in the males were less than half of those found in the female LZ. These may indicate that the change of ACE protein levels may favor the growth of male fetuses by exerting the proliferative effects of angiotensin II on LZ during midpregnancy and by reducing the vasoconstrictive effects of angiotensin II in LZ during late pregnancy. Interestingly, some of the gender differences in RAS expression disappeared in response to maternal protein restriction: for instance, protein levels of AGTR1 in the female and male LZs were similar in LP groups (Fig. 5). Moreover, the overall alteration of RAS in the female and male LZs in response to maternal protein restriction erased the difference in fetal weights between male and female fetuses shown in control groups (Fig. 1). Considering the similar protein levels of ACE2 and AGTR1 in the female and male LZs in LP groups at both Days 14 and 18 of pregnancy (Figs. 3 and 5) and unaltered protein levels of ACE2 by LP at Day 18 of pregnancy (Fig. 4), we propose that the alteration of ACE by LP, specifically the remarkable reduction of ACE protein levels in male LZ at Day 14 of pregnancy (Fig. 3), may be critical for the gender-specific placental programming of adulthood hypertension.

In conclusion, this study is the first to reveal that the expressions of components of the RAS in the rat LZ were affected by maternal protein restriction in a gender- and gestation day-specific manner. According to these results, we propose that reductions in angiotensin (1–7) production in placenta and associated reduction in placental blood flow may be responsible for placental programming of offspring adulthood hypertension by maternal protein restriction during gestation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Ms. Mardelle J. Susman for editorial work on this manuscript and Ms. Elizabeth A. Powell for office support.

Footnotes

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL102866 and R01HL58144.

REFERENCES

- Moritz KM, Johnson K, Douglas-Denton R, Wintour EM, Dodic M. Maternal glucocorticoid treatment programs alterations in the renin-angiotensin system of the ovine fetal kidney. Endocrinology 2002; 143: 4455 4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyrwoll CS, Mark PJ, Mori TA, Puddey IB, Waddell BJ. Prevention of programmed hyperleptinemia and hypertension by postnatal dietary omega-3 fatty acids. Endocrinology 2006; 147: 599 606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert JS, Ford SP, Lang AL, Pahl LR, Drumhiller MC, Babcock SA, Nathanielsz PW, Nijland MJ. Nutrient restriction impairs nephrogenesis in a gender-specific manner in the ovine fetus. Pediatr Res 2007; 61: 42 47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci 1999; 64: 965 974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Robertson EB, Dawson AS, Huffman CA, Bourassa EA, Speth RC, Brosnihan KB, Alexander BT. Placental insufficiency results in temporal alterations in the renin angiotensin system in male hypertensive growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2007; 293: R804 R811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnihan KB, Neves LA, Anton L, Joyner J, Valdes G, Merrill DC. Enhanced expression of Ang-(1–7) during pregnancy. Braz J Med Biol Res 2004; 37: 1255 1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnihan KB, Hering L, Dechend R, Chappell MC, Herse F. Increased angiotensin II in the mesometrial triangle of a transgenic rat model of preeclampsia. Hypertension 2010; 55: 562 566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hering L, Herse F, Geusens N, Verlohren S, Wenzel K, Staff AC, Brosnihan KB, Huppertz B, Luft FC, Muller DN, Pijnenborg R, Cartwright JE, et al. Effects of circulating and local uteroplacental angiotensin II in rat pregnancy. Hypertension 2010; 56: 311 318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy A, Yagil Y, Bursztyn M, Barkalifa R, Scharf S, Yagil C. ACE2 expression and activity are enhanced during pregnancy. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 295: R1953 R1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Lister R, Leitzke A, Goyal D, Gheorghe CP, Longo LD. Antenatal maternal hypoxic stress: adaptations of the placental renin-angiotensin system in the mouse. Placenta 2011; 32: 134 139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Yellon SM, Longo LD, Mata-Greenwood E. Placental gene expression in a rat ‘model' of placental insufficiency. Placenta 2010; 31: 568 575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther T, Jank A, Heringer-Walther S, Horn LC, Stepan H. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor has impact on murine placentation. Placenta 2008; 29: 905 909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves LA, Stovall K, Joyner J, Valdes G, Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Merrill DC, Brosnihan KB. ACE2 and ANG-(1–7) in the rat uterus during early and late gestation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294: R151 R161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades P, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ. Comparative developmental anatomy of the murine and human definitive placentae. Placenta 2002; 23: 3 19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coan PM, Ferguson-Smith AC, Burton GJ. Developmental dynamics of the definitive mouse placenta assessed by stereology. Biol Reprod 2004; 70: 1806 1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung PS, Tsai SJ, Wallukat G, Leung TN, Lau TK. The upregulation of angiotensin II receptor AT(1) in human preeclamptic placenta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2001; 184: 95 102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Shams M, Zhu J, Khalig A, Wilkes M, Whittle M, Barnes N, Ahmed A. Cellular localization of AT1 receptor mRNA and protein in normal placenta and its reduced expression in intrauterine growth restriction. Angiotensin II stimulates the release of vasorelaxants. J Clin Invest 1998; 101: 442 454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata E, Powers RW, Rajakumar A, von Versen-Hoynck F, Gallaher MJ, Lykins DL, Roberts JM, Hubel CA. Angiotensin II decreases system A amino acid transporter activity in human placental villous fragments through AT1 receptor activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2006; 291: E1009 E1016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y, Wen HY, Kellems RE. Angiotensin II inhibits human trophoblast invasion through AT1 receptor activation. J Biol Chem 2002; 277: 24601 24608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton L, Merrill DC, Neves LA, Stovall K, Gallagher PE, Diz DI, Moorefield C, Gruver C, Ferrario CM, Brosnihan KB. Activation of local chorionic villi angiotensin II levels but not angiotensin (1–7) in preeclampsia. Hypertension 2008; 51: 1066 1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher PE, Chappell MC, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Distinct roles for ANG II and ANG-(1–7) in the regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in rat astrocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2006; 290: C420 C426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher PE, Ferrario CM, Tallant EA. Regulation of ACE2 in cardiac myocytes and fibroblasts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2008; 295: H2373 H2379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner SL, Lumbers ER, Symonds EM. Analysis of changes in the renin-angiotensin system during pregnancy. Clin Sci 1972; 42: 479 488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangula PR, Reed L, Yallampalli C. Antihypertensive effects of flutamide in rats that are exposed to a low-protein diet in utero. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005; 192: 952 960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong WY, Wild AE, Roberts P, Willis AC, Fleming TP. Maternal undernutrition during the preimplantation period of rat development causes blastocyst abnormalities and programming of postnatal hypertension. Development 2000; 127: 4195 4202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley-Evans SC, Gardner DS, Jackson AA. Maternal protein restriction influences the programming of the rat hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. J Nutr 1996; 126: 1578 1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Sex-specific effects of prenatal low-protein and carbenoxolone exposure on renal angiotensin receptor expression in rats. Hypertension 2005; 46: 1374 1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC. Maternal low-protein diet in rat pregnancy programs blood pressure through sex-specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2005; 288: R85 R90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins AJ, Wilkins A, Cunningham C, Perry VH, Seet MJ, Osmond C, Eckert JJ, Torrens C, Cagampang FR, Cleal J, Gray WP, Hanson MA, et al. Low protein diet fed exclusively during mouse oocyte maturation leads to behavioural and cardiovascular abnormalities in offspring. J Physiol 2008; 586: 2231 2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautzky-Willer A, Handisurya A. Metabolic diseases and associated complications: sex and gender matter! Eur J Clin Invest 2009; 39: 631 648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano E, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Bautista CJ, Deas M, Guillen L, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. Sex differences in transgenerational alterations of growth and metabolism in progeny (F2) of female offspring (F1) of rats fed a low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation. J Physiol 2005; 566: 225 236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambrano E, Bautista CJ, Deas M, Martinez-Samayoa PM, Gonzalez-Zamorano M, Ledesma H, Morales J, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. A low maternal protein diet during pregnancy and lactation has sex- and window of exposure-specific effects on offspring growth and food intake, glucose metabolism and serum leptin in the rat. J Physiol 2006; 571: 221 230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz KM, Cuffe JS, Wilson LB, Dickinson H, Wlodek ME, Simmons DG, Denton KM. Review: sex specific programming: a critical role for the renal renin-angiotensin system. Placenta 2010; 31 (suppl): S40 S46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ain R, Konno T, Canham LN, Soares MJ. Phenotypic analysis of the rat placenta. In: Soares MJ, Hunt JS. (eds.), Placenta and Trophoblast: Methods and Protocols, Vol. 1 Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc; 2008: 295 313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Sathishkumar KR, Yallampalli U, Balakrishnan M, Li X, Wu G, Yallampalli C. Maternal protein restriction regulates IGF2 system in placental labyrinth. Front Biosci 2012; E4: 1434 1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Glasser SR. Histological and fine structural observations on the placenta of the rat. Acta Anat (Basel) 1968; 69: 542 608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere G, Michaud A, Breton C, VanCamp G, Laborie C, Enache M, Lesage J, Deloof S, Corvol P, Vieau D. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and ACE activities display tissue-specific sensitivity to undernutrition-programmed hypertension in the adult rat. Hypertension 2005; 46: 1169 1174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdes G, Neves LA, Anton L, Corthorn J, Chacon C, Germain AM, Merrill DC, Ferrario CM, Sarao R, Penninger J, Brosnihan KB. Distribution of angiotensin-(1–7) and ACE2 in human placentas of normal and pathological pregnancies. Placenta 2006; 27: 200 207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moritz KM, Mazzuca MQ, Siebel AL, Mibus A, Arena D, Tare M, Owens JA, Wlodek ME. Uteroplacental insufficiency causes a nephron deficit, modest renal insufficiency but no hypertension with ageing in female rats. J Physiol 2009; 587: 2635 2646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson N, Pettersson J, Haafiz A, Ericsson A, Palmberg I, Tranberg M, Ganapathy V, Powell TL, Jansson T. Down-regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction in rats fed a low protein diet. J Physiol 2006; 576: 935 946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malandro MS, Beveridge MJ, Kilberg MS, Novak DA. Effect of low-protein diet-induced intrauterine growth retardation on rat placental amino acid transport. Am J Physiol 1996; 271: C295 C303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal R, Goyal D, Leitzke A, Gheorghe CP, Longo LD. Brain renin-angiotensin system: fetal epigenetic programming by maternal protein restriction during pregnancy. Reprod Sci 2010; 17: 227 238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]