Abstract

Background

Knock-in mice with the common human BDNF Val66Met polymorphism have impaired trafficking of BDNF mRNA to dendrites. Given evidence that local synapse formation is dependent on dendritic translation of BDNF mRNA, it was hypothesized that loss-of-function Met allele mice would show synaptic deficits both at baseline and in response to ketamine, an NMDA antagonist that stimulates synaptogenesis in prefrontal cortex (PFC).

Methods

Whole-cell recordings from layer V medial PFC pyramidal cells in brain slices were combined with 2-photon laser scanning for analysis of WT, Val/Met, and Met/Met mice both at baseline and in response to a low dose of ketamine.

Results

Val/Met and Met/Met mice were found to have constitutive atrophy of distal apical dendrites and decrements in apically-targeted excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) in layer V pyramidal cells of PFC. In addition, spine density and diameter were decreased, indicative of impaired synaptic formation/maturation (synaptogenesis). In Met/Met mice the synaptogenic effect of ketamine was markedly impaired, consistent with the idea that synaptogenesis is dependent on dendritic translation/release of BDNF. In parallel behavioral studies we found that the antidepressant response to ketamine in the forced swim test was blocked in Met/Met mice.

Conclusions

The results demonstrate that expression of the BDNF Met allele in mice results in basal synaptic deficits and blocks synaptogenic and antidepressant actions of ketamine in PFC, suggesting that the therapeutic response to this drug may be attenuated or blocked in depressed patients who carry the loss of function Met allele.

Keywords: antidepressant, dendritic spines, EPSC, hypocretin, major depression, NMDA, serotonin

Introduction

A decrease in BDNF expression in medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and other regions has given rise to the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) hypothesis of major depression (1-4). A human polymorphism in the BDNF gene, which leads to a valine–to–methionine substitution in the proBDNF protein at codon 66 (Val66Met), is carried by ~30% of the general population and has been associated with mild cognitive deficits (5-7). In addition, individuals who carry the Met polymorphism have been reported to have an increased risk of stress-related major depression (8-10). The Val66Met polymorphism impairs activity-dependent secretion of BDNF at synaptic sites (5, 11) and reduces translin-mediated trafficking of BDNF mRNA to dendrites (12). Recently, Chen et al. (13) generated a BDNF Val66Met knock-in mouse exhibiting phenotypic hallmarks of this human polymorphism, providing an animal model for analysis of this human loss-of-function BDNF polymorphism on synaptic function.

In the present study, we focused on the mPFC because of its pivotal role in neurocircuits underlying major depression (14-16). Previously we found that rats exposed to repeated mild restraint stress or the stress hormone corticosterone exhibit atrophy of distal apical dendrites and matching deficits in EPSCs generated in the apical dendrites of layer V pyramidal neurons of the medial PFC (17), The synaptic responses consisted of EPSCs elicited by serotonin (5HT)- and hypocrtin/orexin, which act via apically targeted corticocortical and thalamocortical inputs, respectively (18-19). Given BDNF’s role in modulating activity-dependent synaptic plasticity among mature neurons (20-21), it has been suggested that reductions in EPSCs induced by chronic stress may be mediated by a stress/corticosterone-induced down regulation of BDNF expression (17). It remains to be determined whether mice with the reduced-function BDNF Val66Met knock-in would exhibit similar synaptic deficits.

Recently, it was reported that a single subanesthetic dose of the short-acting NMDA antagonist ketamine rapidly increases the density of functional synaptic spines in mPFC. This synaptogenic effect is preceded by a transient increase in mTOR (“mammalian Target of Rapamycin”) in prefrontal synaptoneurosomes followed within ~2 hours by a prolonged increase in synaptic proteins and a concurrent antidepressant action lasting a week or more (22). These effects are blocked by rapamycin (i.c.v.), a drug that disrupts activation of mTOR, a serine/threonine kinase instrumental in the activation of dendritic translation of synaptic proteins (23). Studies in isolated dendrites demonstrate that puff application of BDNF increases local translation of proteins in an anatomically restricted, mTOR-dependent manner (24). The BDNF Val/66/Met knock-in mouse offers an opportunity to test whether this polymorphism, by impairing BDNF function, interferes with ketamine’s synaptogenic and antidepressant effects.

Methods and Materials

Animals

The generation of the BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice has been previously described (13). Heterozygous Met/Val were bred and the 3 resulting littermate genotypes, Val/Val WT (HP), Val/Met, and Met/Met mice were used. The age of mice was 6-8 months for the electrophysiology and spine morphology experiments and 3 to 10 months for the behavioral studies. Mice were housed and maintained in standard conditions with a 12-h light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. Injections of ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg, i.p.) were made 24 hours prior to preparation of brain slices. Animal use and procedures were in accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines and approved by the Yale University Animal Care and Use Committees.

Brain Slice Preparation

Brain slices were prepared as described (17). Briefly, mice were anesthetized with chloral hydrate (400 mg/kg, i.p.), in adherence to protocols approved by the Yale Animal Care and Use Committee. After decapitation, the brains were removed rapidly and placed in ice-cold (~4°C) artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) in which sucrose (252 mM) was substituted for NaCl (sucrose-ACSF) to prevent cell swelling. A block of tissue containing prefrontal cortex was dissected and coronal slices (400 μm) were cut in sucrose-ACSF with an oscillating-blade tissue slicer (Leica VT1000S) and placed in a submerged recording chamber; bath temperature was raised slowly to 32°C. Known concentrations of drugs dissolved in ACSF, applied through a stopcock arrangement at a fast flow rate (~4 ml/min), reached the slice within 7–10 s. The standard ACSF (pH ~7.35) was equilibrated with 95% O2/5% CO2 and contained 128 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4, 24 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, and 10 mM, D-glucose. A recovery period of ~1–2 h was allowed before commencement of recording.

Electrophysiology

Pyramidal neurons in layer V were visualized by an Olympus BX50WI microscope (×40 or ×60 IR lens) with infrared differential interference contrast (IR/DIC) videomicroscopy (Olympus), as described (19). Low-resistance patch pipettes (3–5 MΩ) were pulled from patch-clamp glass tubing (Warner Instruments) by a Flaming-Brown Horizontal Puller (model P-97; Sutter Instruments). Pipettes were filled with the following solution: 115 mM K gluconate, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM Mg-ATP, 2 mM Na2ATP, 10 mM Na2-phosphocreatine, 0.4 mM Na2GTP, and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.33. Neurobiotin (0.3%) was added to the pipette solution to mark cells for later imaging. Pipettes were first tip-filled with regular patch solution before backfilling with the Neurobiotin solution to avoid ejecting excess dye into the extracellular space of the slice.

Whole-cell recordings were with an Axoclamp-2B amplifier (Axon Instruments). The output signal was low-pass-filtered at 3 KHz, amplified ×100 through Cyberamp, digitized at 15 kHz, and acquired by using pClamp 9.2/Digidata 1320 software (Axon Instruments). Series resistance, monitored throughout the experiment, was usually between 4 and 8 MΩ. To minimize series resistance errors, cells were discarded if series resistance rose above 10 Ω. Postsynaptic currents were in continuous single-electrode voltage-clamp mode (3-kHz low-pass filter cutoff frequency); cells were clamped near their resting potential (~75 mV ± 5 mV) to minimize holding currents. After completion of recording, slices were transferred to 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer and stored overnight at 4°C. Slices were then processed with streptavidin conjugated to Alexa 594 (1/1,000; Invitrogen) for Neurobiotin visualization.

Imaging and Data Analysis

Labeled neurons within layer V of anterior cingulate (Cg1) and prelimbic mPFC (Cg3) were imaged with a two-photon laser scanning system consisting of a Ti:sapphire laser (Mai Tai; Spectra Physics) tuned to wavelength 810 nm and a direct detection Bio-Rad Radiance 2100 MP laser scanner (Zeiss Microimaging) mounted on an Olympus BX50WI microscope with ×40 (0.8 N.A.) or ×60 (0.9 N.A.) water-immersion objectives (Olympus). Total apical and basal dendritic branch length, 3D Z-stacks were reconstructed from ~40–250 sequential scans at low zoom (312 × 312 μm; ×40 lens) at 1-μm steps so as to include the entire apical tuft and basal branches for a given cell within the slice. Total branch length was determined within the 3D matrix of each Z-stack by using Neurolucida 9 (MicroBrightField). Spine density, spine head diameter and spine length analysis were done with Neuolucida Explorer (version 9) on the raw image stacks (2-9 optical sections, 1 μm apart). Spine density was sampled in two zones: (i) tips of apical tuft branches as they approach the pial membrane and (ii) proximal tuft dendrites just distal to the bifurcation. Results were expressed in terms of spine density/10μm.

Forced swim test (FST)

The mouse FST examines the dynamics of transition from an active (struggling) to passive (immobility) mode of coping in an inescapable water-filled glass beaker (11 cm diameter, 15.5 cm high; 10 cm water depth; 25°C water temperature). In each run, 4 mice were video-recorded for 6 minutes using a digital video camcorder (Sony, DCR-SX20). The locations of the animals were counter-balanced based on their experimental groups. Over the first 2 minutes, test mice normally undergo habituation of struggling behavior. Thereafter, the antidepressant or pro-depressive effects of pharmacological and genetic manipulations could be distinguished, indicated by an enhancement of struggling and immobility, respectively, using manual (25) or automated scoring (26). After each run, mice were rescued, dried with a towel and placed near a heat source. All runs were conducted under minimal anxiogenic conditions (27). Video clips were stored as AVI files for offline analyses.

For quantification of animal movement from the FST video files, silhouette alteration method was employed using an automated behavioral tracking system (Videotrack, View Point Life Science, Canada). Each video image is rapidly scanned point-by-point and line-after-line under an 800 × 600 pixel setting (for 40 ms, i.e. 25 images per second). Each point is assigned a luminosity value of 0 to 255 on a gray scale. Values were then converted to a binary image: each pixel is white (0) or black (1). Mice were distinguished from the background by adjusting the sensitivity threshold of this conversion, associating all non-zero pixels in each frame with the silhouette of the mouse (including the head, tail and paws). During movement analyses, degree of silhouette alteration (i.e. the number of pixels coded 0 or 1) changed between successive frames, indicates the level of struggling or immobility displayed. With an integrated threshold algorithm, the threshold for immobility was fine-tuned (at a value of 20) prior to the actual analyses so that the mouse is considered immobile (minimal movements) when it is visually verified as such. This and other automated FST behavioral quantitation have been tested to serve as reliable methods that address the limitations of manual (visual) scoring by experimenters (26, 28).

Drugs

(±)-Ketamine hydrochloride was from Hospira Inc. For the slice experiments, 5-hydroxytryptamine, creatinine sulfate (5-HT) was from Sigma and hypocretin 2 (orexin B) was from American Peptide. Both transmitters were perfused at known concentrations through a stopcock assembly.

Analysis and Statistics

Electrophysiological data were displayed off-line with Clampfit software of pClamp 9.2 (Axon Instruments). Analysis of EPSCs from each 10-s block of (1 s) sweeps was performed with MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft). For statistical analysis, the total branch length was compared between groups by Student’s t-test. The physiological data and the changes in spine density, spine head diameter and spine length were analyzed with repeated measures ANOVA, after a post hoc comparison; values were given as mean ± SEM. EPSC amplitudes were analyzed with the K-S test.

Results

BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice have both apical and basilar dendritic atrophy of mPFC layer V pyramidal cells

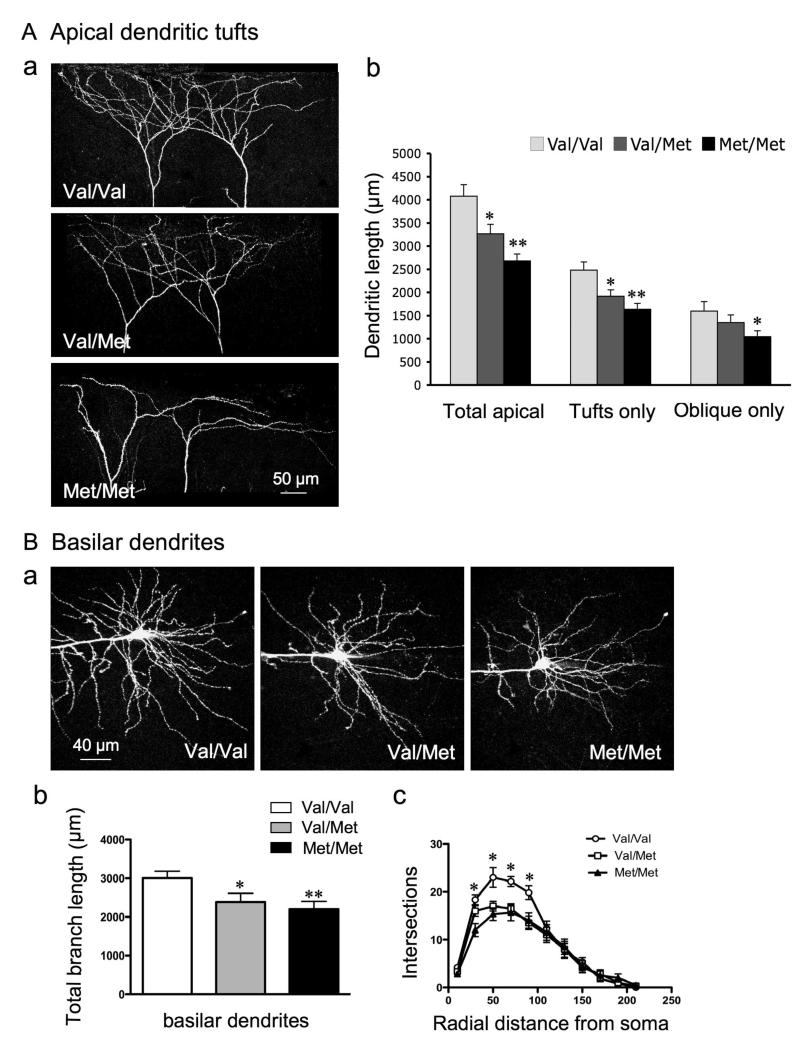

As in a previous study on stress-induced effects (17), we used whole cell patch-clamp recording in combination with imaging by two-photon laser scanning to correlate morphological and electrophysiological changes in the same cells. Compared with Val/Val WT littermate control mice, the Val/Met and Met/Met mice resembled stressed animals in that total branch length of apical dendrites and apical tufts decreased (WT, 4077 ± 247 μm; Val/Met, 3264 ± 204 μm; Met/Met, 2482 ± 150 μm; *p< 0.01, **p<0.001) (Fig. 1A). However, in contrast to stress, there was also a decrease in total length of basilar dendrites in both Val/Met (2382 ± 225 μm) and Met/Met (2200 ± 197 μm) mice as compared with WT Val/Val mice (3006 μm ± 178) (Fig. 1B). Sholl analyses of basilar dendritic structure revealed a significant reduction in dendritic complexity between 20 μm to 100 μm from the soma in Val/Met and Met/Met mice (Fig. 1C). These changes resemble those described previously for Met/Met mice in layer II/III cells of mPFC (29). The reduction of basilar dendrites in Met allele mice corresponds to the deficit in trafficking of BDNF mRNA from the soma to basilar as well as apical fields (12).

Figure 1. mPFC layer V pyramidal cells in BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice have both apical and basilar dendritic atrophy.

A: Apical dendrites: (a) Representative images of Z-stack projections showing atrophy of apical tuft dendrites from two layer V pyramidal cells in Val/Val, Val/Met, and Met/Met mice; (b) Bar graph comparing decrease in branch length of total apical dendrites (i.e., tuft + oblique), apical tuft, and oblique dendrites; oblique branches were decreased in Met/Met mice only. B: Basilar dendrites: (a) Images illustrating basilar dendritic atrophy in Met allele mice (Z-stack projections of basal dendrites from Val/Val, Val/Met and Met/Met mice); (b) Bar graph showing a significant decrease in total length of basal dendrites in Val/Met and Met/Met mice: (c) Sholl analyses of basal dendritic structure revealing a significant decrease in basilar dendrite intersections in Val/Met and Met/Met mice between 20 and 100 μm from the soma.

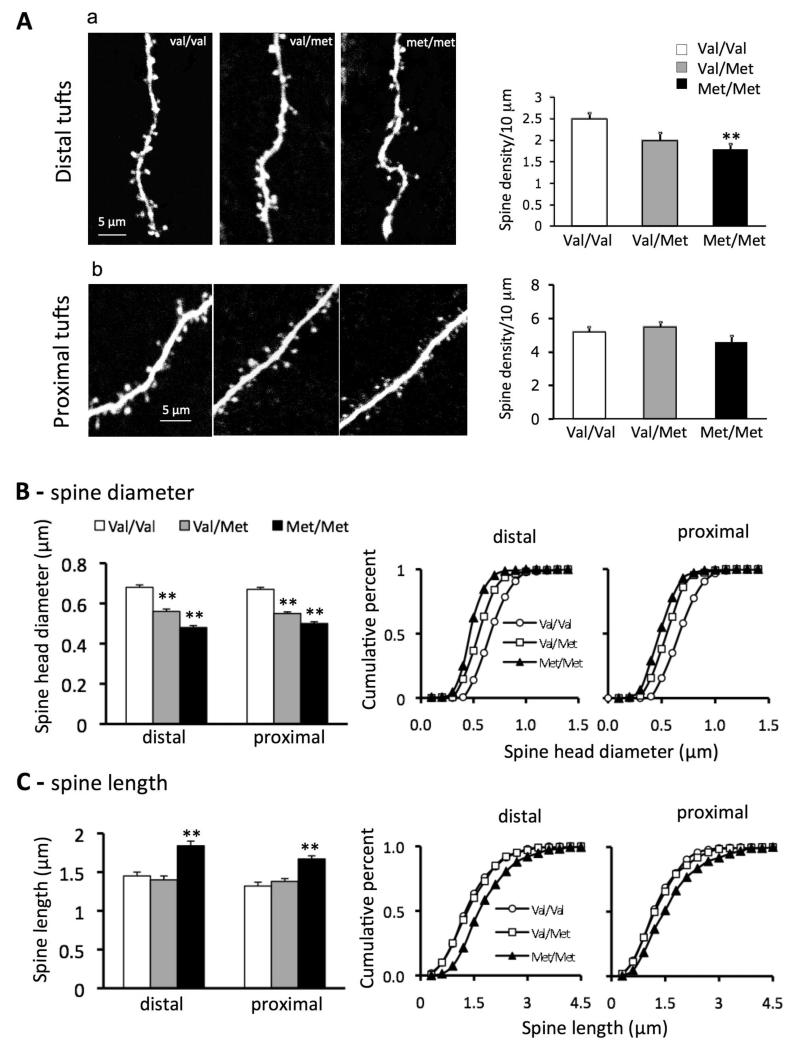

Apical tuft dendrites of layer V cells of Val/Met and Met/Met mice show a reduction in spine density and maturation

As shown in Fig. 2, distal but not proximal apical tuft dendritic spine density was significantly decreased in layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons in Met/Met mice compared to Val/Val littermate control mice (Met/Met, 1.9 ± 0.2 /10 μm; Val/Val, 2.5 ± 0.12/10 μm; p = <0.02); Val/Met mice had a non-significant decrease in distal spine density (Fig. 2 A). In addition, spine head diameter showed a gene-dose dependent decrease in both distal (Val/Val 0.68±0.012, Val/Met 0.56±0.012, and Met/Met 48±0.01) and proximal apical tuft dendrites (Fig. 2 A, B). Spine length also showed a significant increase in both distal and proximal dendritic branches but only in Met/Met mice (Fig2. A, C). Taken together, these changes resulted in a shift from mushroom-like spines (>0.75 μm) toward long, thin spines. These changes are similar to those found in pyramidal neurons of cortex and hippocampus in transgenic mice expressing a dominant negative of the BDNF receptor tropomyosin-related kinase B (TrkB) (30). Conversely, conditional deletion of downstream negative regulators of TrkB of increases filopodial motility and synaptic formation (31).

Figure 2. BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice have deficits in spine density and spine morphology in apical tuft dendritic branches of layer V mPFC pyramidal cells.

A. Representative images showing spine density and morphology in distal (a) and proximal (b) tuft dendrites in Val/Val, Val/Met and Met/Met groups; adjacent bar graphs comparing spine density in distal and proximal zones in the three groups of mice. Note: dendritic spine density is reduced in distal but not proximal apical tuft in Met/Met mice (Met/Met, 1.9 ± 0.2 / 10 μm; Val/Val, 2.5 ± 0.12/10 μm; p = 0.02). B. spine diameter: Bar graphs (left) of spine head diameter showing a gene-dose dependent decrease in apical turf spine diameter for both distal Val/Val (0.68±0.012 μm) versus Val/Met (0.56 ± 0.012 μm) and Met/Met (0.48 ± 0.01 μm), and proximal Val/Val (0.67 ± 0.01 μm) versus Val/Met (0.55 ± 0.008 μm) and Met/Met (0.5 ± 0.009 μm) segments; cumulative fraction line graphs (right) for distal and proximal tuft segments showing gene dose-dependent decrease in spine diameter. C. spine length: bar graphs (left) showing an increase in spine length for Met/Met group only; cumulative fraction cline graphs (right) for distal and proximal tuft spine length; note increase in spine length only in the Met/Met group (1.84 ± 0.06 μm and 1.67 ± 0.04 μm) as compared to Val/Val (1.45 ± 0.05 μm, 1.32 ± 0.05 μm) and Val/Met (1.4 ± 0.05 μm 1.38 ± 0.04 μm) groups.

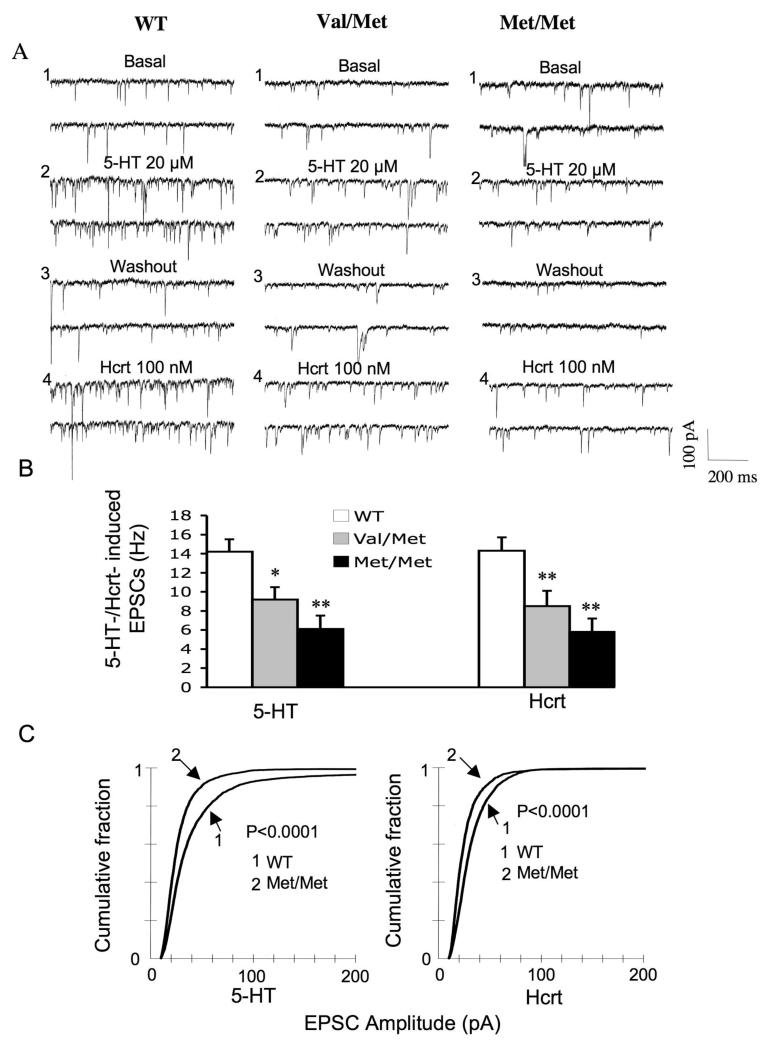

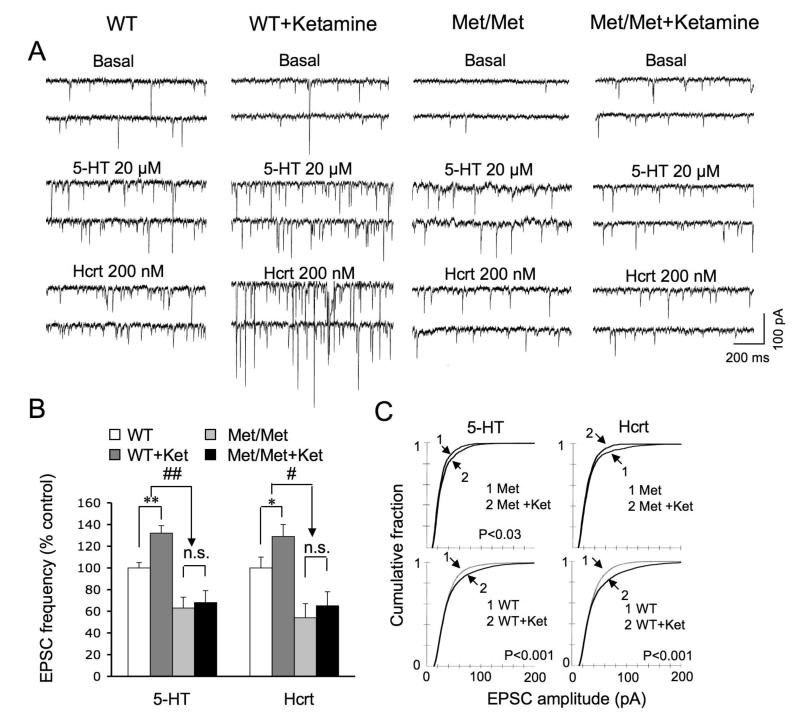

Morphological changes in layer V pyramidal cells in Val/Met and Met/Met mice are associated with a reduction in the frequency and amplitude of 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSCs

Paralleling the reduction in branch length and shift toward thin, immature spines, we found that the mean frequency of 5-HT-induced EPSCs were decreased to 65±9% (p=0.05) and those of hypocretin to 60±11% (p<0.05) in Val/Met mice compared to littermate Val/Val mice (Fig. 3). The changes were even greater in Met/Met compared to WT mice, which showed a reduction in frequency of 5-HT-induced EPSCs to 43±10% (p<0.01 and hypocretin-induced EPSCs to 40±10% (p<0.01). Similarly, EPSC amplitudes showed a decrease both for 5-HT and hypocretin in Val/Met mice (p< 0.0001 for 5-HT, z value = 7.5; p < 0.0001 for hypocretin, z value ± 6.25; K-S test) and Met/Met mouse neurons (p< 0.0001 for 5-HT, z value = 8.8; p < 0.0001 for hypocretin, z value + 7.01) (Fig. 3C). These results reveal a graded genetic effect in heterozygous and homozygous Met allele mice compared to WT mice with respect to both morphological and functional changes within layer V mPFC pyramidal neurons.

Figure 3. Morphological changes in layer V pyramidal cells in BDNF Val/Met and Met/Met mice are associated with a reduction in the frequency and amplitude of 5-HT and hypocretin (hcrt)-induced EPSCs.

(A) Sample traces of EPSCs in mPFC layer V pyramidal cells fromVal/Val, Val/Met and Met/Met mice; (B) Mean frequencies ± SEM of 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSCs are reduced in Val/Met and Met/Met groups compared with that of the Val/Val group. Asterisk indicates statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (c) Cumulative probability distributions showing a significant decrease in EPSC amplitude in the Met/Met group for both 5-HT and Hcrt (P < 0.0001 for 5-HT, KS-z value = 8.8; p < 0.0001 for Hcrt, KS-z value = 7.5).

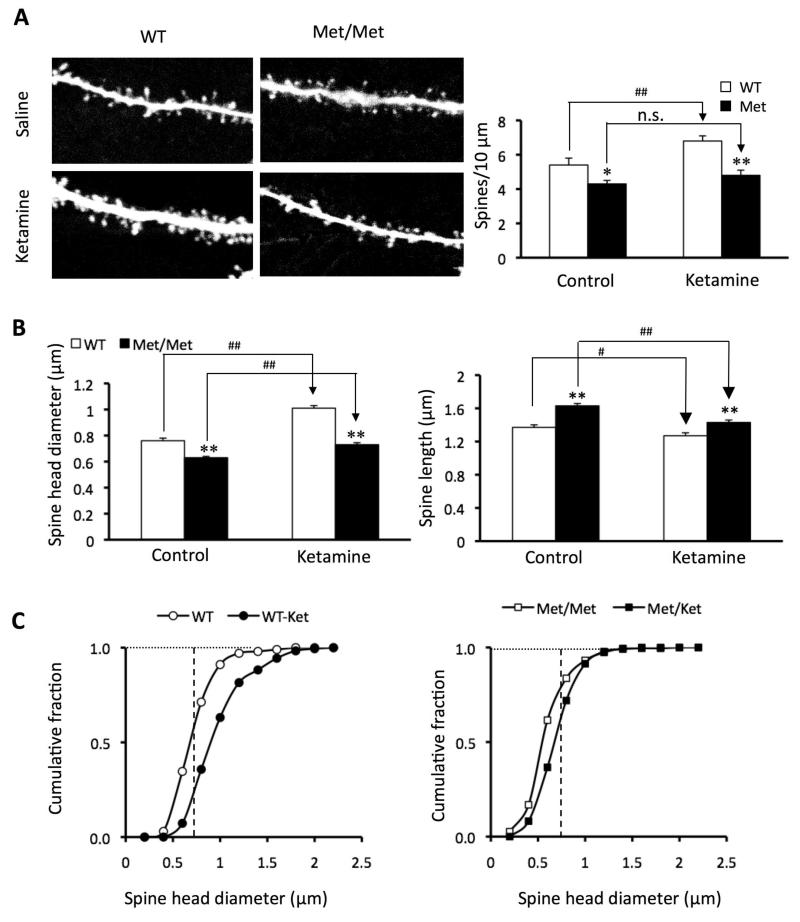

Ketamine-induction of synaptogenesis is impaired in Met/Met mice

Recently we reported that a single injection of ketamine in normal rats rapidly increases the density and function of apical dendritic spines in the layer V PFC pyramidal cells via the protein kinase mTOR, an activator of dendritic translation of synaptic proteins (22). As BDNF lies upstream of mTOR (24, 32-33), we hypothesized that ketamine’s effectiveness in reversing the deficits in synaptic morphology and function in Met/Met mice would be diminished. To test this possibility, WT and Met/Met mice were examined 24 hrs after injection of a single dose of ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg, i.p.). As previously seen in normal rats, ketamine induced an increase in spine density in distal and proximal segments of the apical tuft 24 hrs after injection in Val/Val mice (Fig. 4A), Additionally, ketamine increased spine head diameter in Val/Val mice. (Fig. 4A-C), resulting in an expansion of the mushroom spine (>0.75 μ) population. However, in Met/Met mice ketamine failed to increase spine density or spine head diameter. Moreover, in Met/Met mice ketamine failed to increase the frequency of 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSCs (Fig. 5A,B), paralleling the lack of change in spine density (Fig. 4A). In contrast, in Met/Met mice ketamine did produce a small increase in spine diameter in the sub-0.75 μ range (Fig. 4C) associated with a slight increase in EPSC amplitude (Fig. 5C). The latter results indicate that despite an overall blunting, the synaptogenic effects of ketamine in Met/Met mice were not totally blocked.

Figure 4. Synaptogenic effects of ketamine are blunted in BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice.

Mice received ketamine injections (10 mg/kg, i.p.). (A) Representative images of high zoom Z-stack projections of proximal segments of the apical tuft dendrites. Bar graph (right) shows decrease in spine density in Met allele group; this deficit was not reversed by ketamine treatment (p<0.05*/#; p<0.01**/##). (B) Bar graphs showing decrease in mean spine head diameter and increase in spine length in apical tuft Met group. (C) Cumulative fraction curves for the tuft spine diameter. Plot on left shows a marked increase in population of large mushroom spines in the ketamine group compared to WT (>0.75 μm diameter; dashed line); plot on right shows virtually no ketamine-induced increase in mushroom spines (>0.75 μm) in Met/Met mice as compared to WT mice. Spine analysis was performed using Neurolucida Explorer, version 9; results are given as mean ± SEM.

Figure 5. Ketamine-induction of EPSC frequency and amplitude are reduced or eliminated in BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice.

((A) Sample whole cell voltage-clamp traces of 5-HT and hypocretin-induced EPSCs in layer V cells from vehicle and ketamine treated Val/Val and Met/Met mice (24 hr post drug treatment); ketamine was administered as described in Figure 4. (B) Bar graphs showing, in contrast to Val/Val group, ketamine fails to increase the frequency of 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSCs in the Met/Met group (n = 15 neurons/group; *p< 0.05, ANOVA), There was no significant difference between basal EPSC frequency in WT (6.1±1) vs, Met/Met (5±0.7) or WT+Ket (10.4±1.1) or Met/Met+Ket (8.3±0.9), although there was a trend toward a decrease in both cases. (C) Cumulative probability distributions showing the ability of ketamine to increase EPSC amplitude is substantially reduced in Met/Met group as compared to WT group. Note that 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSC responses were from the same set of neurons that were analyzed for spine density in Figure 4.

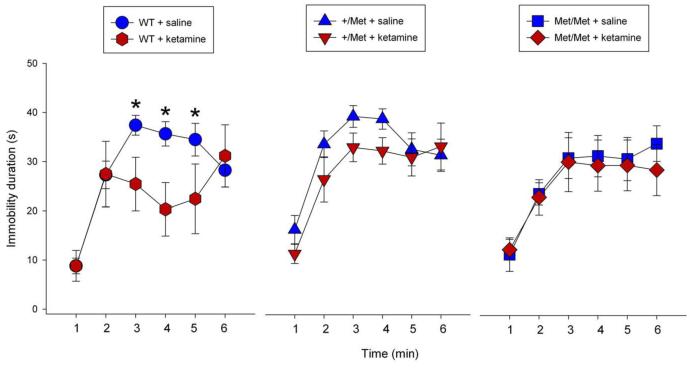

Antidepressant effect of ketamine in the forced swim test (FST) is blocked in Met/Met mice

Previous studies demonstrated that ketamine produces a rapid and sustained antidepressant response in the FST (22, 34). Given that the synaptogenic actions of ketamine were blocked in Met/Met mice (see above), we hypothesized that the behavioral effects of ketamine would also be blocked. Consistent with a previous report in WT mice (34), we observed that ketamine significantly decreased (p = 0.02) immobility time in the FST 24 hours after administration (Figure 6), but there was no significant difference in immobility time between ketamine and saline in Val/Met or Met/Met knock-in mice (Figure 6). A two factor (ketamine × time) mixed-design ANOVA shows that there is a highly significant interaction in WT mice [F(5,55) = 3.40, p 0.01]. Simple main effects test conducted between ketamine and saline treatments for each 1-min interval revealed that ketamine significantly attenuated immobility duration minutes 3-5 [3rdmin, F(1,66)=4.12, p 0.05; 4th min, F(1,66)=6.33, p 0.05; and 5th min, F(1,66)=4.01, p 0.05], consistent with an antidepressant effect in WT mice. For the Val/Met mice there was no significant ketamine × time interaction [F(5,60) = 0.62, p = 0.686]. Ketamine attenuated immobility duration on the 3rd and 4th minute, but failed to achieve significance [F(1,72)=4.12, p 0.05 and F(1,72)=4.12, p 0.05, respectively]. For the Met/Met mice there was no significant ketamine × time interaction [F(5,60) = 0.22, p = 0.953]; the effect of ketamine in attenuating immobility duration was completely abrogated [3rd min, F(1,72)=0.02, p=0.895; 4th min, F(1,72)=0.10, p=0.752; 5th min, F(1,72)=0.04, p=0.834]. There was no effect of ketamine on immobility over the first 2 min in any genotype, indicating a lack of effect on the habituation (or struggling) phase of the FST; also there were no significant effects between the three vehicle treated genotype groups in the absence of ketamine administration. These findings are consistent with a recent report that the antidepressant effects of ketamine are blocked in an inducible BDNF null line (35).

Figure 6. Antidepressant response to ketamine in the FST is attenuated in BDNF Val66Met knock-in mice.

Mice were injected with vehicle or ketamine (10 mg/kg) and tested in the FST 24 hr later as described in Methods. (a-c) The time spent immobile over the first 6 mins is shown for each genotype ± ketamine. A two factor (ketamine × time) mixed-design ANOVA conducted on the FST data from each genotype. For the Wild Type (WT) mice there is a highly significant interaction, F(5,55) = 3.40, p ≤ 0.01. Simple main effects test conducted between ketamine and saline treatments for each 1-min interval revealed that ketamine significantly attenuated immobility duration on the 3rd minute, F(1,66)=4.12, p ≤ 0.05; 4th minute, F(1,66)=6.33, p ≤ 0.05; and 5th minute, F(1,66)=4.01, p ≤ 0.05. This is consistent with ketamine’s antidepressant activity. WT+ketamine, n=6; WT+saline, n=7; *p ≤ 0.05. For the Val/Met (+/Met) mice, there was no significant ketamine × time interaction, F(5,60) = 0.62, p = 0.686. Ketamine attenuated immobility duration on the 3rd and 4th minute, but failed to achieve significance; F(1,72)=4.12, p ≤ 0.05 and F(1,72)=4.12, p ≤ 0.05, respectively. +/Met+ketamine, n=7; +/Met+saline, n=7. For the Met/Met mice there was no significant ketamine × time interaction F(5,60) = 0.22, p = 0.953. In these mice, the effect of ketamine in attenuating immobility duration was completely abrogated [3rd minute, F(1,72)=0.02, p=0.895; 4th minute, F(1,72)=0.10, p=0.752; 5th minute, F(1,72)=0.04, p=0.834; 6th minute, F(1,72)=0.79, p=0.378. Met/Met+ketamine, n=7; Met/Met+saline, n=7. There was no effect of ketamine on immobility over the first 2 min in any genotype, indicating a lack of effect on the habituation (or struggling) phase of the FST.

Discussion

Previous studies have found that trafficking of BDNF mRNA to dendrites, which depends on its association with the mRNA binding protein translin (12), is essential for normal BDNF-mediated synapse formation and plasticity (36-38), We find that in mice with the human BDNF Val/Met genetic variant (11) exhibit basal synaptic deficits together with a diminished ability to respond to the rapidly acting synaptogenic and antidepressant effects of ketamine. These effects include: 1) a gene dose-dependent constitutive reduction in distal spine density and spine head diameter of mPFC layer V pyramidal cells; 2) a marked attenuation of 5-HT- and hypocretin-induced EPSCs; and 3) blockade of ketamine-induction of synapatogenic and behavioral actions in the FST. These findings indicate that a deficiency in dendritic BDNF mRNA and protein may underlie both constitutive synaptic deficits and blockade of ketamine’s synaptogenic and behavioral effects.

Constitutive changes in Val/Met mice: similarities and differences with stress-induced changes in WT animals

The constitutive atrophy of distal apical dendrites in layer V mPFC pyramidal cells in Val/Met and Met/Met mice resembles that seen previously in rats under chronic restraint stress (17). The stress-induced changes in layer V cells appear to be a function of distance from the soma, selectively affecting distant apical dendrites (17, 39); selective sensitivity of apical dendrites to stress has also been found in layer II/II pyramidal cells (40-41). Nevertheless, the changes in Met/Met mice differ from stress in that basilar dendrites are also affected. This difference may be explained by the fact that in Val/Met mice there is a severe impairment in translin-dependent trafficking of the variant BDNF mRNA, which affects nearby basilar dendrites as well as more distant dendrites in the apical field (12). If such deficits are also present in humans that carry the Val66Met polymorphism, they may contribute to the increased risk of major depression after early life stress (10) or in elderly populations exposed to recurrent lifelong stress (7, 9, 42). In addition, such constitutive synaptic changes could underlie the cognitive deficits that have been observed non-depressed subjects with the Val/Met polymorphism (5-6,43). Paradoxically, in non-depressed subjects, levels of depressive symptoms are higher in Val/Val than Val/Met individuals (44-45).

BDNF dependence of ketamine-induced rapid synaptogenesis

Early studies demonstrated that subanesthetic but not anesthetic doses of ketamine rapidly produce an increase in extracellular glutamate levels in mPFC, leading to an AMPA receptor-dependent induction of the acute behavioral effects of this drug (46). Subsequently, the stimulation of AMPA receptors has been shown to trigger longer-term cellular and antidepressant behavioral responses to ketamine (22, 34). In vitro studies reveal that positive modulation of AMPA receptors stimulates BDNF release, which leads in turn to activation of the BDNF receptor TrkB and, further downstream, increased mTOR-dependent dendritic mRNA translation (32). Recently, we reported that ketamine rapidly activates the mTOR pathway, leading to increased expression of postsynaptic proteins (i.e., PSD95 and GluR1) in PFC of rats that were associated with an increase in the number and function of dendritic spines (22). The present results extend these findings by showing that ketamine fails to induce a synaptogenic effect in BDNF Met/Met mice, implicating BDNF in the mechanism of action of this drug. As yet there are no in vivo studies directly showing that ketamine increases BDNF release in mPFC. However, a recent study reports that a single systemic injection of ketamine produces a transient increase in BDNF protein in hippocampus (35). While analysis of BDNF at different time points in mPFC would be interesting it is beyond the scope of the current study.

Taken together, the above studies suggest the following scenario: 1) ketamine acutely increases extracellular glutamate levels, leading to pyramidal cell burst firing and stimulation AMPA receptors; 2) AMPA receptor stimulation induces the release of BDNF, which in turn activates its receptor TrkB; and 3) downstream from TrkB, activation of mTOR initiates dendritic translation of synaptic proteins and ultimately synaptogenesis. The interference by the Met allele with translin-dependent dendritic trafficking BDNF mRNA as well dendritic secretion of BDNF (11-13), suggests that the Val66Met polymorphism interferes with this ketamine-induced sequence of event. It is also possible that the basal decrease in spine density and function in the BDNF Met mice precludes the response to ketamine, although in chronic stress animals, in which there is also a decrease in spine number and function, ketamine still induces synaptogenic and antidepressant behavioral responses (Li et al., 2011).

Clinical implications

The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism represents the first alteration in a neurotrophin gene linked to clinical pathology in affective disorders. Thus, the cognitive impairments in individuals carrying the Met polymorphism (5) are associated with a reduction in volume of various brain regions including the PFC and hippocampus (47-50). The reductions in PFC gray matter volumes were significantly greater in the Met/Met compared to the Val/Met bipolar patients, correlating with relative memory deficits in the same subjects (50). A graded reduction in gray matter volume in humans corresponds to the gene dose-response relationship we observed for loss of dendritic branches and spine density in layer V cells of the BDNF Val/Met gene knock-in mice. These synaptic deficits have implications for both intracortical and subcortical connectivity. In particular, the layer V pyramidal cells of mPFC give rise to major corticolimbic projection pathways innervating regions such as the locus coeruleus, dorsal raphe nucleus, ventral tegmental area, nucleus accumbens, and amygdala (51) that are within circuits implicated in mood disorders (15-16, 52).

The therapeutic implications of the failure of BDNF Met allele mice to respond to the synaptogenic effect of ketamine are also of interest. A single subanesthetic dose of ketamine produces a rapid and relatively long-lasting antidepressant response in a majority of otherwise treatment-resistant patients (~70%) with major depression or bipolar depression (53-55). Moreover, a single dose of ketamine is effective in rapidly resolving suicidal ideation in emergency room situations (56-57). However, the reason for the lack of response in the remaining ~30% of patients is not clear. Recently, it was reported that mice with an inducible knockout of the BDNF gene fail to show the expected antidepressant-like behavioral responses to ketamine (35). The present study confirms that a similar resistance to ketamine occurs in BDNF Met/Met mice. As yet it is not known if patients homologous for the Met polymorphism are also resistant to ketamine. A meta-analysis of clinical studies with “standard” antidepressants (e.g., SSRIs) not only does not show an overall negative influence of the Met allele on outcome there are some studies reporting an enhanced treatment response (58). Perhaps this can be explained by the finding in mouse models that these drugs transactivate TrkB independently of BDNF (59). It remains to be determined if the ~30% of patients that are resistant to the rapid antidepressant effect of ketamine includes disproportionally those who carry the loss-of-function BDNF Met allele. If so, it may be possible to bypass the BDNF deficit by treating non-responders with BDNF-mimetic compounds that can act directly on TrkB to activate the mTOR synaptogenic pathway.

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grants MH17871, MH093897, and the State of Connecticut.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures The authors have no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts pertaining to this work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–27. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castren E, Voikar V, Rantamaki Role of neurotrophic factors in depression. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2007;7:18–21. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinowich K, Manji H, Lu B. New insights into BDNF function in depression and anxiety. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1089–93. doi: 10.1038/nn1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwivedi Y. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: role in depression and suicide. Ann Med. 2009;42:87–96. doi: 10.3109/07853890903485730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan MF, Kojima M, Callicott JH, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Bertolino A, Zaitsev E, Gold B, Goldman D, Dean M, Lu B, Weinberger DR. The BDNF val66met polymorphism affects activity-dependent secretion of BDNF and human memory and hippocampal function. Cell. 2003;112:257–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hariri AR, Goldberg TE, Mattay VS, Kolachana BS, Callicott JH, Egan MF, Weinberger DR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism affects human memory-related hippocampal activity and predicts memory performance. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6690–4. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06690.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris SE, Fox H, Wright AF, Hayward C, Starr JM, Whalley LJ, Deary IJ. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism is associated with age-related change in reasoning skills. Molec Psychiatry. 2006;11:505–513. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J-M, Stewart R, Kim S-W, Yang S-J, Shin I-S, Kim Y-H, Yoon J-S. Interactions between life stressors and susceptibility genes (5-HTTLPR and BDNF) on depression in Korean elders. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyajima F, Ollier W, Mayes A, Jackson A, Thacker N, Rabbitt P, Pendleton N, Horan M, Payton A. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor polymorphism Val66Met influences cognitive abilities in the elderly. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:411–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2007.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatt JM, Nemeroff CB, Dobson-Stone C, Paul RH, Bryant RA, Schofield PR, Gordon E, Kemp AH, Williams LM. Interactions between BDNF Val66Met polymorphism and early life stress predict brain and arousal pathways to syndromal depression and anxiety. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:681–95. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen ZY, Patel PD, Sant G, Meng CX, Teng KK, Hempstead BL, Lee FS. Variant brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) (Met66) alters the intracellular trafficking and activity-dependent secretion of WT BDNF in neurosecretory cells and cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4401–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0348-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiaruttini C, Vicario A, Li Z, Baj G, Braiuca P, Wu Y, Lee FS, Gardossi L, Baraban JM, Tongiorgi E. Dendritic trafficking of BDNF mRNA is mediated by translin and blocked by the G196A (Val66Met) mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16481–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902833106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZY, Jing D, Bath KG, Ieraci A, Khan T, Siao CJ, Herrera DG, Toth M, Yang C, McEwen BS, Hempstead BL, Lee FS. Genetic variant BDNF (Val66Met) polymorphism alters anxiety-related behavior. Science. 2006;314:140–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1129663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Struct Funct. 2008;213:93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayberg HS. Targeted electrode-based modulation of neural circuits for depression. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:717–725. doi: 10.1172/JCI38454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krishnan V, Nestler EJ. Linking molecules to mood: new insight into the biology of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1305–20. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.10030434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu RJ, Aghajanian GK. Stress blunts serotonin- and hypocretin-evoked EPSCs in prefrontal cortex: role of corticosterone-mediated apical dendritic atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:359–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706679105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ. Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology. 1997;36:589–99. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(97)00051-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lambe EK, Aghajanian GK. Hypocretin (orexin) induces calcium transients in single spines postsynaptic to identified thalamocortical boutons in prefrontal slice. Neuron. 2003;40:139–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00598-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poo MM. Neurotrophins as synaptic modulators. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:24–32. doi: 10.1038/35049004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu B. Acute and long-term synaptic modulation by neurotrophins. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:137–50. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)46010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li N, Lee B, Liu RJ, Banasr M, Dwyer JM, Iwata M, Li XY, Aghajanian G, Duman RS. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science. 2010;329:959–64. doi: 10.1126/science.1190287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoeffer CA, Klann mTOR signaling: at the crossroads of plasticity, memory and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2009;33:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takei N, Inamura N, Kawamura M, Namba H, Hara K, Yonezawa K, Nawa H. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor induces mammalian target of rapamycin-dependent local activation of translation machinery and protein synthesis in neuronal dendrites. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9760–9. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porsolt RD, Bertin A, Jalfre M. Behavioral despair in mice: a primary screening test for antidepressants. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1977;229(2):327–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayashi E, Shimamura M, Kuratani K, Kinoshita M, Hara H. Automated experimental system capturing three behavioral components during murine forced swim test. Life Sci. 2011;88(9-10):411–7. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelliher P, Connor TJ, Harkin A, Sanchez C, Kelly JP, Leonard BE. Varying responses to the rat forced-swim test under diurnal and nocturnal conditions. Physiol Behav. 2000;69(4-5):531–9. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00213-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kulikov AV, Morozova MV, Kulikov VA, Kirichuk VS, Popova NK. Automated analysis of antidepressants’ effect in the forced swim test. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;191(1):26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu H, Wang Y, Pattwell S, Jing D, Liu T, Zhang Y, Bath KG, Lee FS, Chen ZY. Variant BDNF Val66Met polymorphism affects extinction of conditioned aversive memory. Neurosci. 2009;29:4056–4064. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5539-08.2009. † . * [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chakravarthy S, Saiepour MH, Bence M, Perry S, Hartman R, Couey JJ, Mansvelder HD, Levelt CN. Postsynaptic TrkB signaling has distinct roles in spine maintenance in adult visual cortex and hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1071–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506305103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luikart BW, Zhang W, Wayman GA, Kwon CH, Westbrook GL, Parada LF. Neurotrophin-dependent dendritic filopodial motility: a convergence on PI3K signaling. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7006–12. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0195-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jourdi H, Hsu YT, Zhou M, Qin Q, Bi X, Baudry M. Positive AMPA receptor modulation rapidly stimulates BDNF release and increases dendritic mRNA translation. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8688–97. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6078-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Slipczuk L, Bekinschtein P, Katche C, Cammarota M, Izquierdo I, Medina JH. BDNF activates mTOR to regulate GluR1 expression required for memory formation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6007. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeng S, Zarate CA, Jr, Du J, Schloesser RJ, McCammon J, Chen G, Manji HK. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: role of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Autry AE, Adachi M, Nosyreva E, Na ES, Los MF, Cheng PF, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature10130. doi:10.1038/nature 10130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tongiorgi E, Baj G. Functions and mechanisms of BDNF mRNA trafficking. Novartis Found Symp. 2008;289:136–47. doi: 10.1002/9780470751251.ch11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.An JJ, Gharami K, Liao GY, Woo NH, Lau AG, Vanevski F, Torre ER, Jones KR, Feng Y, Lu B, Xu B. Distinct role of long 3′ UTR BDNF mRNA in spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal neurons. Cell. 2008;134:175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soulé J, Messaoudi E, Bramham CR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and control of synaptic consolidation in the adult brain. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:600–4. doi: 10.1042/BST0340600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldwater DS, Pavlides C, Hunter RG, Bloss EB, Hof PR, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Structural and functional alterations to rat medial prefrontal cortex following chronic restraint stress and recovery. Neuroscience. 2009;164:798–808. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.08.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown SM, Henning S, Wellman CL. Mild, short-term stress alters dendritic morphology in rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15:1714–22. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radley JJ, Rocher AB, Miller M, Janssen WG, Liston C, Hof PR, McEwen BS, Morrison JH. Repeated stress induces dendritic spine loss in the rat medial prefrontal cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2006;16:313–20. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagel IE, Chicherio C, Li SC, von Oertzen T, Sander T, Villringer A, Heekeren HR, Bäckman L, Lindenberger U. Human aging magnifies genetic effects on executive functioning and working memory. Front Hum Neurosci. 2008;2:1–8. doi: 10.3389/neuro.09.001.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soliman F, Glatt CE, Bath KG, Levita L, Jones RM, Pattwell SS, Jing D, Tottenham N, Amso D, Somerville LH, Voss HU, Glover G, Ballon DJ, Liston C, Teslovich T, Van Kempen T, Lee FS, Casey BJ. A genetic variant BDNF polymorphism alters extinction learning in both mouse and human. Science. 2010;327:863–866. doi: 10.1126/science.1181886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilt LM, Sander LC, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Simen AA. The BDNF Val66Met polymorphism predicts rumination and depression differently in young adolescent girls and their mothers. Neurosci Lett. 2007;429:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duncan LE, Hutchison KE, Carey G, Craighead WE. Variation in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) gene is associated with symptoms of depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;115:215–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D. Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: a novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2921–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR, Jr, Todd RD, Reich T, Vannier M, Raichle ME. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. 1997;386:824–7. doi: 10.1038/386824a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pezawas L, Verchinski BA, Mattay VS, Callicott JH, Kolachana BS, Straub RE, Egan MF, Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor val66met polymorphism and variation in human cortical morphology. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10099–102. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2680-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frodl, Schule C, Schmitt G, Born C, Baghai T, Zill P, Bottlender R, Rupprecht R, Bondy B, Reiser M, Moller H-J, Meisenzahl EM. Association of the brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism with reduced hippocampal volumes in major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:410–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuo K, Walss-Bass C, Nery FG, Nicoletti MA, Hatch JP, Frey BN, Monkul ES, Zunta-Soares GB, Bowden CL, Escamilla MA, Soares JC. Neuronal correlates of brain-derived neurotrophic factor Val66Met polymorphism and morphometric abnormalities in bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1904–13. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gabbott PL, Warner TA, Jays PR, Salway P, Busby SJ. Prefrontal cortex in the rat: projections to subcortical autonomic, motor, and limbic centers. J Comp Neurol. 2005;492:145–77. doi: 10.1002/cne.20738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Savitz J, Drevets WC. Bipolar and major depressive disorder: neuroimaging the developmental-degenerative divide. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009;33:699–771. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–4. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Luckenbaugh DA, Charney DS, Manji HK. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diazgranados N, Ibrahim L, Brutsche NE, Newberg A, Kronstein P, Khalife S, Kammerer WA, Quezado Z, Luckenbaugh DA, Salvadore G, Machado-Vieira R, Manji HK, Zarate CA., Jr A randomized add-on trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant bipolar depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010a;67:793–802. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price RB, Nock MK, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Effects of intravenous ketamine on explicit and implicit measures of suicidality in treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:522–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diazgranados N, Ibrahim LA, Brutsche NE, Ameli R, Henter ID, Luckenbaugh DA, Machado-Vieira R, Zarate CA., Jr Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in patients with treatment-resistant major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010b;71:1605–11. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsai1 S-J, Hong C-J, Liou Y-J. Effects of BDNF polymorphisms on antidepressant action. Psychiatry Investig. 2010;7:236–242. doi: 10.4306/pi.2010.7.4.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rantamäki T, Vesa L, Antila H, Di Lieto A, Tammela P, Schmitt A, et al. Antidepressant drugs transactivate TrkB neurotrophin receptors in the adult rodent brain independently of BDNF and monoamine transporter blockade. PLoS One. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020567. (Epub Jun 7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]