Abstract

Aims

Compared to DSM-IV nicotine dependence, proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder (NUD) would lower the threshold from 3 to 2 symptoms, and increase the number of criteria used for diagnosis from 7 to 11. The impact of the proposed changes on nicotine disorder prevalence, and the concurrent validity of diagnostic criteria were examined.

Design

Cross-sectional survey to compare DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 algorithms.

Setting and Participants

Adolescent (N=179) and young adult (N=292) past year cigarette users recruited from addictions treatment.

Measurements

Semi-structured clinical interview to evaluate DSM-IV nicotine dependence, and 10 of the 11 proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria; 30-day Time Line Follow-Back; and Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND).

Findings

Prevalence of proposed DSM-5 NUD (2-symptom threshold) was much higher (adolescents: 69%, young adults: 86%) than DSM-IV nicotine dependence (33% and 60%, respectively), although prevalence of DSM-5 severe NUD (4-symptom threshold) was similar to DSM-IV nicotine dependence. Concurrent validity analyses in both samples indicated consistent support for DSM-5 severe NUD diagnosis (4-symptoms) but not for the moderate NUD (2-symptoms) diagnosis, which had modest relations with only FTND score. IRT analyses indicated strong support for the new Craving item, but not for the proposed Interpersonal Problems and Hazardous Use items.

Conclusions

The proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder criteria have substantial limitations when applied to adolescents and young adults, and appear to have low concurrent validity.

Keywords: DSM, nicotine dependence, diagnostic concordance

Proposed Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), substance use disorder (SUD) criteria (www.dsm5.org) would involve more change for nicotine, compared to other drug classes in DSM-IV (1–3). Specifically, proposed DSM-5 nicotine use disorder (NUD) criteria would increase the number of criteria used for diagnosis from 7 to 11, with the addition of three DSM-IV abuse criteria (used for most other substances in DSM-IV with the exception of nicotine), and a new Craving criterion. In addition, the threshold for nicotine diagnosis would be lowered from 3 to 2 symptoms. The implications of proposed changes to NUD criteria with regard to the prevalence and validity of nicotine diagnoses, and diagnostic concordance across iterations of DSM warrant study prior to the publication of DSM-5 in 2013.

DSM-IV recognizes two SUDs: substance abuse and dependence. A diagnosis of substance abuse requires 1 of 4 criteria representing certain negative consequences resulting from substance use: recurrent failure to meet Role Obligations, Hazardous Use, Interpersonal Problems, and Legal Problems. DSM-IV substance dependence requires the co-occurrence of 3 of 7 criteria within 1-year: Tolerance, Withdrawal, use more or longer than intended (Larger/Longer), failed attempts or strong desire to limit use (Quit/Cut), Much Time spent using, Reduce Activities in order to use, and psychological or physical problems exacerbated or caused by use (Psych/Phys). Importantly, DSM-IV acknowledges that some of the generic dependence criteria used to determine a nicotine diagnosis do not appear to directly apply to nicotine or require some explanation as to how they might apply to nicotine (2: page 243; 3: page 264).

Proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria include 11 symptoms (1): 3 DSM-IV abuse criteria (i.e., Role Obligations, Hazardous Use, Interpersonal Problems), all 7 DSM-IV dependence criteria, and a new Craving symptom (i.e., strong desire to engage in use). Proposed DSM-5 NUD requires the co-occurrence of two or more of 11 symptoms within 1-year. Presence of 2–3 symptoms represents “moderate” NUD, and 4 or more symptoms represents “severe” NUD. The use of a criterion set that combines abuse and dependence symptoms in DSM-5 is based on the idea that the proposed criteria represent a single dimension, which has been supported for alcohol and some other drugs (e.g., 4, 5, 6). To date, only 1 study has examined the dimensionality of proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria (7), and like other studies of nicotine-related symptoms (e.g., 8, 9), found support for a single dimension. Because few existing datasets include data relevant to examining proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria, we attempted to replicate (cf. 7) the dimensionality and performance characteristics of 10 of the 11 (Role Obligation not assessed) proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria.

Decisions to include new diagnostic criteria, such as Craving, need to consider whether the criteria improve diagnosis in terms of reliability, validity, and case identification (10). This study examined concordance of DSM-IV dependence and proposed DSM-5 NUD, and evidence for concurrent validity of the two algorithms in adolescents and young adults, who were initially recruited from substance use treatment. This study addresses the DSM-5 workgroup’s call for field trials in patient samples because patient samples tend to have more, and more severe symptoms, compared to the general population (1). We focus on adolescents and young adults because nicotine addiction often has origins in adolescence, and peak rates of tobacco use emerge in young adulthood (11).

For analyses comparing the prevalence of DSM-IV dependence and proposed DSM-5 NUD, we predicted greater prevalence of proposed DSM-5 NUD compared to DSM-IV, due to proposed DSM-5’s lower threshold and expanded array of symptoms. We also predicted that lowering the threshold to 2 symptoms would result in limited concurrent validity for proposed DSM-5 NUD, relative to DSM-IV nicotine dependence. We tested the unidimensionality of proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria, and used Item Response Theory (IRT) to examine symptom performance characteristics. We predicted that the 3 DSM-IV abuse items would show poor psychometric performance (e.g., low rates of endorsement) when included in the proposed DSM-5 algorithm.

Method

Adolescent and Young Adult sample characteristics

Adolescent (N=179 past year cigarette users, age 14–18) and young adult (N=292 past year cigarette users, age 18–35) samples were recruited through the Pittsburgh Adolescent Alcohol Research Center from community-based substance use treatment. Tobacco cessation was not a standard component of treatment (12). In the adolescent sample, most (65%) participants were male; 91% identified as White, 5% as Black, and 4% as other ethnicity (e.g., bi-racial). Adolescents had a mean age of 16.7 (SD=1.2), and represented a range in socioeconomic status (SES) (range 1 [high SES] to 5 [low SES], mean=2.5, SD=1.1) (13). Most (96.1%) reported cigarette use in the past month, with 92.7% reporting use in the week prior to the assessment. A majority had a past year DSM-IV marijuana diagnosis (89.3%), and 53.1% met criteria for a past year DSM-IV alcohol diagnosis. Other DSM-IV drug use disorders included: cocaine (13.4%), opiate (19.0%), sedative (5.0%), stimulant (5.0%), and hallucinogen (4.5%).

Half (53%) of the young adult sample was male; 83% identified as White, 17% as Black, and 0.3% as other ethnicity (e.g., bi-racial). Mean age at the nicotine assessment was 26.6 (SD=4.1). Most (87.7%) reported cigarette use in the past month, with 84.6% reporting use in the week prior to the assessment. Young adults represented the full range in SES (mean=3.0, SD=1.1). In the year prior to assessment, one-third met criteria for a past year DSM-IV marijuana diagnosis (32.6%) and one-third (32.9%) met criteria for a past year DSM-IV alcohol diagnosis. Other DSM-IV drug use disorders included: cocaine (11.6%), opiate (10.9%), sedative (2.0%), stimulant (1.7%), and hallucinogen (0.3%).

Recruitment and Assessment Procedures

Shortly after treatment admission, patients were invited to participate in a longitudinal research project (adolescent sample recruited as 14–18 year olds in 2004–2009; young adults recruited as 14–18 year olds in 1990–2000). Among those approached for participation, most (74% in the adolescent and 77% in the young adult samples) provided written informed consent/assent after description of the study, and completed baseline. In both samples, among those who expressed interest in participation, there were no demographic differences between those who did versus did not complete baseline. Demographic characteristics of both samples were similar to those of youth admitted to publicly funded substance use treatment in the United States (14).

Data for the adolescent sample came from the baseline assessment (2–2.5 hours long), which was usually completed within two weeks of treatment entry. For the young adult sample, data came from the first follow-up (3–4 hours long) after baseline at which nicotine symptoms and daily cigarette use in the past 30 days were assessed. Follow-ups for the young adult sample occurred at 1-, 3-, 5-, 7-years after baseline, at Age 25, and Age 30; average retention was >80% through Age 30. In the young adult sample, only one assessment per subject was used: 6% provided data at 3-years, 19% at 5-years, 51% at Age 25, and 24% at Age 30. Samples were administered the same set of nicotine-related measures. Participants were compensated for their time. The University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Measures

Cigarette use

The Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB; 15) calendar method was used to estimate quantity of cigarettes consumed per day, and total number of cigarettes consumed in the 30 days prior to the assessment. TLFB data have good reliability and validity (16–18).

DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 substance use disorder (SUD) diagnoses and symptoms

Highly trained interviewers administered an adapted version of the Semi-structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV SUDs (SCID; 19, 20). The adapted SCID evaluates the presence of DSM-IV SUD symptoms and diagnoses, and exploratory symptoms (e.g., Craving), including ages of symptom on and offset with good reliability (20, 21). The exploratory Craving symptom included probes such as, “Did you ever have a persistent and serious craving, desire, or need for cigarettes when you weren’t smoking?” Applied to nicotine, the Hazardous Use symptom included prompts such as, “Have you ever smoked in situations where it was dangerous to smoke, for example, smoking in bed, or when pumping gasoline?” The exploratory Interpersonal Problems symptom included questions such as, “Did your smoking cause problems between you and your family members, or make existing problems much worse?” For any symptom to be rated as present, recurrence (e.g., occurrence ≥3 times within 1 year), and distress or impairment were required. Two-week re-test for nicotine symptom ratings were moderate to high; intraclass correlation =.89 for total DSM-IV nicotine symptom count (21).

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

The FTND (22) includes 6 items (see citation 22 for items and scoring details; possible range: 0–10). Only “current daily cigarette smokers” completed the FTND (adolescent n=114; young adult n=198). Internal consistency reliability was moderate (Cronbach’s alpha for adolescents= .55, young adults= .64), but within range for the FTND (23). A high level of dependence corresponds to FTND score ≥6 (22), representing 23.7% (27 of 114) of adolescents and 42.4% (84 of 198) of young adults.

Unidimensionality and IRT analyses

Mplus 5.21 (24) was used to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), testing a single factor model (cf. 7, 8, 9) for 10 of the 11 proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria (dichotomous ratings), separately in each sample. Given unidimensionality, a 2-parameter IRT model provided information in each sample on difficulty (β parameter) and discrimination (α parameter) for each symptom. Symptom difficulty is the value on the latent nicotine severity dimension at which the probability of symptom endorsement is 50%. Positive difficulty values indicate symptoms that are likely to be endorsed among individuals with higher than average levels of nicotine severity; negative values indicate symptoms that are more likely to be endorsed by individuals with lower than average nicotine severity. Symptom discrimination provides information on which symptoms best differentiate among individuals with different levels of nicotine problem severity, such that higher values indicate greater discrimination. A MIMIC-model approach was used to test for differential item functioning (DIF) across the two samples (25), controlling for recent level of use (i.e., total number of cigarettes in the past 30 days).

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive data on cigarette use. The majority of adolescents (75.4%, n=135) and young adults (92.5%, n=270) reported at least 1 proposed DSM-5 NUD symptom (adolescent mean=2.8, SD=2.2; young adult mean=4.1, SD=2.2) in the year prior to the assessment. Among adolescents, 33.0% met criteria for a past year DSM-IV nicotine dependence diagnosis, whereas 68.7% met criteria for a past year proposed DSM-5 NUD (moderate: 29.6%; severe: 39.1%). Among young adults, 59.6% met criteria for past year DSM-IV nicotine dependence, and 86.0% met criteria for a past year proposed DSM-5 NUD (moderate: 23.6%; severe: 62.3%). In both samples, proposed DSM-5 criteria identified more cases with a diagnosis than DSM-IV (adolescent: χ2= 44.2, df=1, p<.001; young adult: χ2= 50.1, df=1; p<.001), although prevalence of proposed DSM-5 “severe” NUD did not differ from DSM-IV nicotine dependence (adolescent: χ2= 1.2, df=1, p=.27; young adult: χ2= 0.3, df=1; p=.56).

Table 1.

Descriptive data on DSM-IV and Proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Diagnoses, Cigarette Use, and FTND score

| Adolescent sample | Young Adult sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ave Cig/Day (n=179) | Total Cig, Past 30 days (n=179) | FTND score† (n=114) | Ave Cig/Day (n=292) | Total Cig, Past 30 days (n=292) | FTND score† (n=198) | |

| Past year smokers: Mean (SD) | 10.42 (7.29) | 287.80 (217.98) | 3.96 (2.03) | 13.69 (9.54) | 395.03 (293.04) | 4.64 (2.30) |

| DSM-IV | ||||||

| No diagnosis | 7.96 (6.33) | 212.04 (183.02) | 3.22 (1.90) (n=68) | 8.81 (7.65) | 249.53 (232.78) | 3.07 (1.87) (n=68) |

| Nicotine dependence | 15.41 (6.58) | 441.90 (202.64) | 5.06 (1.72) (n=46) | 17.00 (9.29) | 493.71 (289.07) | 5.47 (2.07) (n=130) |

| Proposed DSM-5 | ||||||

| No diagnosis | 4.66 (3.74) | 126.75 (111.96) | 2.61 (1.85) (n=28) | 4.48 (6.04) | 112.58 (181.90) | 2.46 (1.85) (n=13) |

| Nicotine disorder: moderate | 9.78 (6.01) | 257.15 (181.35) | 3.45 (1.86) (n=33) | 11.29 (7.01) | 323.26 (213.64) | 3.16 (1.84) (n=49) |

| Nicotine disorder: severe | 15.51 (6.73) | 439.86 (206.32) | 5.00 (1.69) (n=53) | 16.67 (9.46) | 485.87 (292.00) | 5.39 (2.10) (n=136) |

Notes: Ave=Average, SD= standard deviation, Cig=Cigarettes, FTND= Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence.

For FTND (“current daily smokers”), adolescent n=114, young adult n=198.

In both samples, agreement between DSM-IV and proposed DSM-5 (≥2 symptoms) on the presence of a past year nicotine diagnosis was moderate (adolescent kappa=.37, young adult kappa=.39) (Table 2). There was high agreement between presence of DSM-IV nicotine dependence and proposed DSM-5 “severe” NUD (adolescent kappa=.82, young adult kappa=.87). All cases of DSM-IV nicotine dependence were covered by proposed DSM-5 NUD.

Table 2.

Cross-classification of DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence Diagnosis with Proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder

| N=179 adolescents: past year cigarette users | No DSM-IV diagnosis | DSM-IV Subthreshold (1–2 symptoms of 7) | DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence (≥3 symptoms of 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No DSM-5 diagnosis | 44 | 0 | 0 |

| DSM-5 subthreshold (1 symptom of 10) | 9 | 3 | 0 |

| DSM-5 Moderate NUD (2–3 symptoms of 10) | 3 | 48 | 2 |

| DSM-5 Severe NUD (≥4 symptoms of 10) | 0 | 13 | 57 |

| N=292 Young adults: past year cigarette users | No DSM-IV diagnosis | DSM-IV Subthreshold (1–2 symptoms of 7) | DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence (≥3 symptoms of 7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No DSM-5 diagnosis | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| DSM-5 subthreshold (1 symptom of 10) | 7 | 14 | 0 |

| DSM-5 Moderate NUD (2–3 symptoms of 10) | 2 | 62 | 5 |

| DSM-5 Severe NUD (≥4 symptoms of 10) | 0 | 13 | 169 |

Notes: All 7 DSM-IV dependence symptoms were assessed. 10 of the 11 proposed DSM-5 nicotine use disorder symptoms were assessed (Role Obligations was not assessed).

Evidence for concurrent validity of DSM-IV nicotine dependence was satisfactory in both samples (Table 1), in that no diagnosis and dependence categories differed on average cigarettes per day (adolescent: t= −7.3, df=177, p<.001; young adult: t= −7.9, df=290, p<.001), and total cigarettes in the past month (adolescent: t= −7.62, df=177, p<.001; young adult: t= −8.0, df=281.5, p<.001). For FTND score, current daily smokers with and without a DSM-IV diagnosis differed (adolescent: t= −5.3, df=112, p<.001; young adult: t= −8.0, df=196, p<.001).

Evidence for concurrent validity was less consistent for proposed DSM-5 NUD, particularly when comparing proposed moderate DSM-5 NUD with no diagnosis. Those with no diagnosis versus NUD (moderate and severe combined) differed on average cigarettes per day (adolescent: t= −10.4, df=172.6, p<.001; young adult: t= −7.2, df=290, p<.001), total cigarettes in the past month (adolescent: t= −9.6, df=173.9, p<.001; young adult: t= −7.2, df=290, p<.001), and FTND score (adolescent: t= −4.2, df=142, p<.001; young adult: t= −4.3, df=227, p<.001). ANOVA comparing proposed DSM-5 moderate and severe NUD categories with no diagnosis indicated overall group differences for average cigarettes per day (adolescent: F[2,176]=56.3, p<.001; young adult: F[2,289]=37.7, p<.001), total cigarettes in the past month (adolescent: F[2,176]=51.5, p<.001; young adult: F[2,289]=37.3, p<.001), and FTND score (adolescent: F[2,111]=18.5, p<.001; young adult: F[2,195]=29.8, p<.001). In both samples, pair-wise comparisons indicated significant differences (p<.01) between no diagnosis, moderate, and severe NUD on average cigarettes per day, and total cigarettes in the past month. However, in both samples, among current daily smokers, pair-wise comparisons for FTND score indicated that proposed moderate NUD did not differ from no diagnosis (p>.15), although cases with proposed severe NUD differed from no diagnosis on FTND score (p<.01).

The most prevalent nicotine symptoms in both samples were Craving, Tolerance, and Much Time (Table 3). CFA indicated satisfactory fit of the 10 proposed DSM-5 symptoms to a single factor model in both samples (adolescent: Confirmatory Fit Index [CFI]=.96, Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI]=.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA]=.08; young adult: CFI=.98, TLI=.97, RMSEA=.04); all symptoms had significant loadings (p≤.05; supplementary table). Given reasonable fit, IRT was conducted.

Table 3.

Prevalence and IRT parameters for DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence and Proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder Symptoms*

| Adolescent (n=179) | Young Adult (n=292) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | IRT diffic | IRT discrim | n | % | IRT diffic | IRT discrim | ||

| DSM-5 only | Craving | 112 | 62.6 | −0.37 | 1.72 | 236 | 80.8 | −1.03 | 1.58 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Tolerance | 103 | 57.5 | −0.20 | 3.89 | 191 | 65.4 | −0.52 | 1.17 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Much time | 65 | 36.3 | 0.41 | 1.62 | 196 | 67.1 | −0.54 | 1.40 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Withdrawal | 62 | 34.6 | 0.58 | 0.93 | 126 | 43.2 | 0.39 | 0.49 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Quit/Cut Down | 54 | 30.2 | 1.02 | 0.59 | 161 | 55.1 | −0.22 | 0.74 |

| DSM-5 only | Interpersonal Problems | 40 | 22.3 | 1.90 | 0.44 | 19 | 6.5 | 6.34 | 0.25 |

| DSM-5 only | Hazardous Use | 30 | 16.8 | 1.67 | 0.70 | 95 | 32.5 | 0.78 | 0.71 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Larger/Longer | 22 | 12.3 | 1.64 | 1.00 | 118 | 40.4 | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Psych/Physical Problems | 12 | 6.7 | 4.70 | 0.34 | 45 | 15.4 | 2.01 | 0.59 |

| DSM-IV and 5 | Reduce Activities | 3 | 1.7 | 4.84 | 0.49 | 18 | 6.2 | 2.09 | 1.09 |

Notes:

Proposed DSM-5 criterion “recurrent tobacco use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations” (Role Obligations) was not assessed.

IRT diffic= Item response theory difficulty parameter estimate. IRT discrim= Item response theory discrimination parameter estimate. Psych/Physical Problems= Psychological/Physical Problems

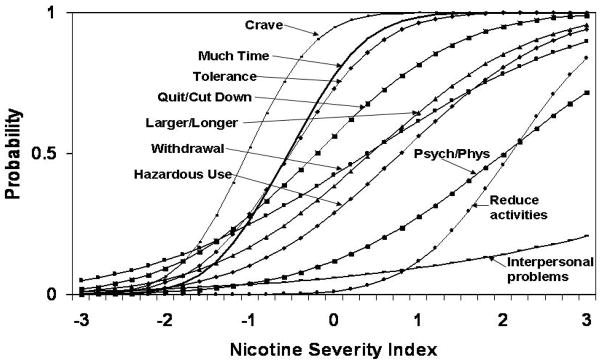

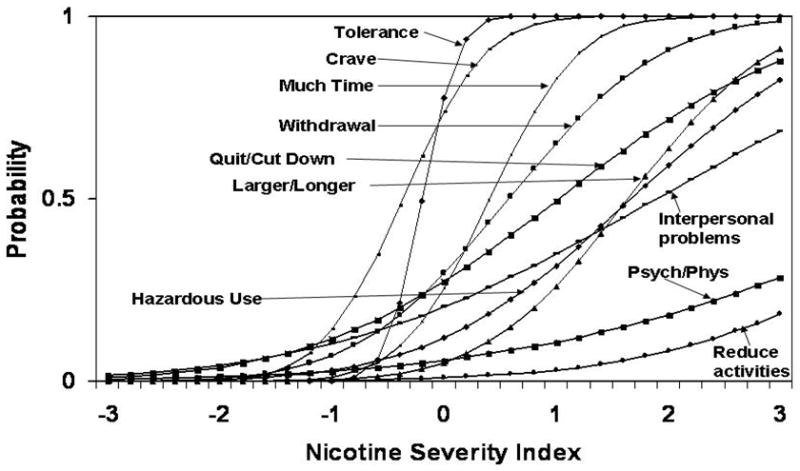

In IRT, the item characteristic curve (ICC) plots (Figures 1 and 2) symptom difficulty and discrimination at different values of the latent nicotine severity construct (i.e., the horizontal axis). ICCs farther to the right generally indicate greater symptom difficulty. Steeper ICC slope indicates greater ability of the symptom to discriminate between individuals with different levels of nicotine severity. In adolescents, symptom difficulty ranged from −0.37 (Craving) to 4.84 (Reduce Activities); in young adults, symptom difficulty ranged from −1.03 (Craving) to 6.34 (Interpersonal Problems) (Table 3). In adolescents, symptom discrimination parameters ranged from 0.34 (Psych/Physical problems) to 3.89 (Tolerance); in young adults, discrimination ranged from 0.25 (Interpersonal Problems) to 1.58 (Craving). In both samples, Craving had the lowest difficulty, and relatively high discrimination. Psych/Physical Problems, Hazardous Use, Interpersonal Problems, and Reduce Activities had relatively high difficulty and low discrimination in both samples. DIF analyses, controlling for level of use, indicated that Craving, Withdrawal, Much Time, Reduce Activities, and Hazardous Use showed minimal DIF, and could be used as “anchor items.” Tests of DIF for the remaining items indicated that Tolerance and Interpersonal Problems had lower difficulty in adolescents than young adults, and Larger/Longer and Quit/Cut had lower difficulty in young adults (p<.05).

Figure 1.

Adolescent sample: Item Characteristic Curves for DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence and Proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder Symptoms

Note: n=135 for adolescent sample Item Response Theory analyses

Figure 2.

Young Adult Sample: Item Characteristic Curves for DSM-IV Nicotine Dependence and Proposed DSM-5 Nicotine Use Disorder Symptoms

Note: n=270 for young adult sample Item Response Theory analyses

Discussion

The prevalence of cases with a past year NUD increased substantially in both adolescent and young adult treatment samples using proposed DSM-5, compared to DSM-IV criteria. However, prevalence of DSM-5 NUD “severe” was generally consistent with DSM-IV nicotine dependence. The increase in prevalence with proposed DSM-5 NUD was due largely to its lower threshold (i.e., ≥2 symptoms), and to the relatively high prevalence of a new Craving criterion. Proposed DSM-5 NUD would result in discontinuity with DSM-IV estimates of nicotine disorder prevalence. Proposed DSM-5 NUD’s greater coverage of symptomatic cases would increase heterogeneity among those identified with NUD (e.g., in severity), which may affect treatment response (e.g., increased placebo effect; 26, 27), particularly at the lower boundary of diagnosis.

The increase in nicotine disorder prevalence from DSM-IV to proposed DSM-5 NUD raises questions regarding the validity of the proposed 2-symptom threshold. An important purpose of diagnosis is to reliably distinguish health from disease (26, 28). The distinction between health and disease is important in determining treatment need (26, 28, 29), and identifying underlying etiologic processes that can inform effective treatment (26, 28). In this regard, proposed DSM-5 NUD (moderate and severe combined) was distinguished from no diagnosis on the three concurrent validators examined. However, among current daily smokers in both samples, proposed moderate DSM-5 NUD did not differ from no diagnosis on FTND score, suggesting possible limitations in the concurrent validity of the proposed 2-symptom threshold. Specifically, the FTND concurrent validity results suggest that the proposed algorithm may be vulnerable to “false positive” diagnoses at its lower bound. This limitation may have less impact with regard to treatment decisions, because clinical diagnoses may not show strong evidence for validity, but might still be useful in clinical situations (30). Some tobacco interventions (e.g., 5As; 31) do not depend on determining diagnostic status, suggesting limited impact of proposed revisions for some clinical applications. In contrast to the use of diagnosis for treatment purposes, error in classification reduces the likelihood of detecting true associations in etiologic research, because a valid diagnosis or phenotype is more likely to correspond to an underlying biological process than an invalid diagnosis (26, 28). Vulnerability to false positive phenotypes may limit utility of proposed DSM-5 NUD for etiologic research (28, 32). The increase in NUD prevalence with proposed DSM-5 criteria raises questions regarding what proportion of regular smokers warrant a diagnosis of NUD.

An important caveat is that the external validators examined in this study were limited. As concurrent validators, a growing literature indicates that level of cigarette use has variable associations with dependence measures (e.g., 33), and FTND score has shown low to moderate correlations with DSM-based measures of severity (e.g., 34, 35). Proposed DSM-5 NUD diagnosis and symptoms need to be examined in relation to stronger measures of dependence, such as urges to smoke during the day among continuing smokers, the prediction of cessation outcomes, and withdrawal symptoms during a quit attempt (e.g., 36, 37). Research is also needed to examine optimal thresholds to reliably and identify NUD, and to examine multiple (e.g., biological, cognitive) concurrent and predictive indicators of validity. Statistical significance for certain validity analyses might be obtained with larger samples.

In addition to lowering the diagnostic threshold from 3 to 2-symptoms, proposed DSM-5 NUD would add 4 new symptoms to the algorithm. Results support unidimensionality of proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria (cf. 7), although certain symptoms (e.g., Interpersonal Problems) had relatively low factor loading, suggesting their limitations as indicators of the construct. Craving, a new proposed item, had relatively low difficulty and high discrimination in IRT analyses (cf. 8, 38), which suggest its potential utility as an early indicator of disorder. These results contrast with those from an Israeli sample (7), in which Craving was the fifth most prevalent among the 11 proposed NUD symptoms. Cross-study differences in the relative prevalence of Craving highlight the need for a clear operational definition of the criterion, since alternative wordings can impact rates of symptom endorsement and NUD prevalence (e.g., 35, 39, 40). Clarification is needed on whether Craving should be considered a component of nicotine withdrawal (e.g., 37), or a more appetitive (rather than withdrawal-related) phenomenon (37, 41–43).

Two other new proposed DSM-5 criteria, Hazardous Use and Interpersonal Problems, were in the mid- to high range of symptom difficulty, as found in another study (7), but showed relatively poor discrimination here. The applicability of these two symptoms, and other SUD criteria (e.g., Reduced Activities, Role Obligation), to nicotine is controversial because when applied to nicotine, the symptoms have limited face validity and generally low prevalence (33, 37). The effect of including less applicable, low prevalence criteria in an algorithm could increase “error” (e.g., an item’s poor discrimination can suggest false positive endorsements, especially at the lower range of severity) in the algorithm (33). In addition, Interpersonal Problems showed the greatest DIF across the two samples, with adolescents more likely to endorse this symptom at lower levels of severity than young adults, suggesting potential limitations in the performance of this proposed criterion.

Study limitations warrant comment. The proposed DSM-5 NUD criterion Role Obligations was not assessed because of its limited face validity when applied to nicotine (cf., 33). In an Israeli sample (7), Role Obligations had very low prevalence, suggesting that its exclusion here likely marginally underestimated the prevalence of proposed DSM-5 NUD. Study findings are not generalizable beyond youth and young adults, most of whom were Caucasian, recruited from treatment, and who reported other substance use. This study cannot provide population-based estimates of nicotine diagnosis prevalence. Although it is possible that withdrawal symptoms related to other substances could have been confused with those for nicotine, interviewers probed substance-specific withdrawal symptoms when polysubstance use was reported. The MIMIC-model approach used to examine DIF permits inclusion of covariates (e.g., level of consumption), but tested only uniform (differences in item thresholds across groups), not also non-uniform (differences in item discrimination) DIF (25). Thus, analyses reported here may underestimate DIF.

The substantial increase in the number of cases identified by proposed DSM-5 NUD, compared to DSM-IV nicotine dependence, along with the possibility that the proposed 2-symptom threshold may not clearly distinguish proposed moderate DSM-5 NUD from no diagnosis, raise concerns regarding the validity of the proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria, particularly at the lower range of severity. Although some new symptoms show utility (e.g., Craving), others have limitations (e.g., Interpersonal Problems). A higher threshold (e.g., ≥4 of 11 symptoms) for proposed DSM-5 NUD is recommended. Further tests of concurrent and predictive validity of proposed DSM-5 NUD criteria are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for the conduct of the research and preparation of the manuscript was provided by funding from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA014357, K02 AA018195, R21 AA017128, R01 AA13397).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Development. 2010 November 1; Available from: http://www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

- 2.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Text Revision. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borges G, Ye Y, Bond J, Cherpitel CJ, Cremonte M, Moskalewicz J, Swiatkiewicz G, Rubio-Stipec M. The dimensionality of alcohol use disorders and alcohol consumption in a cross-national perspective. Addiction. 2010;105:240–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelhorn H, Hartman C, Sakai J, Stallings M, Young S, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt J, Hopfer C, Crowley T. Toward DSM-V: An item response theory analysis of the diagnostic process for DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:1329–39. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318184ff2e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartman CA, Gelhorn H, Crowley TJ, Sakai JT, Stallings M, Young SE, Rhee SH, Corley R, Hewitt JK, Hopfer CJ. Item response theory analysis of DSM-IV cannabis abuse and dependence criteria in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:165–73. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815cd9f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shmulewitz D, Keyes KM, Wall MM, Aharonovich E, Aivadyan C, Greenstein E, Spivak B, Weizman A, Frisch A, Grant BF, Hasin D. Nicotine dependence, abuse and craving: dimensionality in an Israeli sample. Addiction. 2011;106:1675–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03484.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strong D, Kahler CW, Colby SM, Griesler PC, Kandel D. Linking measures of adolescent nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strong DR, Kahler CW, Ramsey SE, Brown RA. Finding order in the DSM-IV nicotine dependence syndrome: A Rasch analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;72:151–62. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyes KM, Krueger RF, Grant BF, Hasin DS. Alcohol craving and the dimensionality of alcohol disorders. Psychol Med. 2011;41:629–40. doi: 10.1017/S003329171000053X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2009. Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National findings. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JJ. Failure to treat tobacco use in mental health and addiction treatment settings: A form of harm reduction? Drug Alc Depend. 2010;110:177–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollingshead A. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven, CT: Author; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Series #S-45, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 09-4360. Rockville, MD: Office of Applied Studies; 2009. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS) highlights - - 2007 National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback users’ manual. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donohue B, Azrin NH, Strada MJ, Silver NC, Teichner G, Murphy H. Psychometric evaluation of self- and collateral timeline follow-back reports of drug and alcohol use in a sample of drug-abusing and conduct-disordered adolescents and their parents. Psychol Addict Behav. 2004;18:184–9. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donohue B, Hill HH, Azrin NH, Cross C, Strada MJ. Psychometric support for contemporaneous and retrospective youth and parent reports of adolescent marijuana use frequency in an adolescent outpatient treatment population. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1787–97. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, Turner CW, Peterson TR. Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 4- and 7-month assessments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:802–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin CS, Pollock NK, Bukstein O, Lynch KG. Inter-rater reliability of the SCID alcohol and substance use disorders section among adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;59:173–6. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00119-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chung T, Martin CS, San Pedro R, Shriberg RF, Cornelius JR. Retest reliability and discrepancy interview for DSM-IV alcohol, cannabis, and nicotine diagnoses in treated adolescents. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28 (supplement):111A. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piper M, McCarthy DE, Baker TB. Assessing tobacco dependence: A guide to measure evaluation and selection. Nicotine and Tobacco Research. 2006;8:339–51. doi: 10.1080/14622200600672765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woods CM. Evaluation of MIMIC-Model methods for DIF testing with comparison to two-group analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 2009;44:1–27. doi: 10.1080/00273170802620121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer RE. A commentary on ‘Addiction and dependence in DSM-V’. Addiction. 2011;106:873–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelenberg AJ, Thase ME, Meyer RE, Goodwin FK, Katz MM, Kraemer HC, Potter WZ, Shelton RC, Fava M, Khan A, Trivedi MH, Ninan PT, Mann JJ, Bergeson S, Endicott J, Kocsis JH, Leon AC, Manji HK, Rosenbaum JF. The history and current state of antidepressant clinical trial design: a call to action for proof-of-concept studies. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1513–28. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulze TG, McMahon FJ. Defining the phenotype in human genetic studies: Forward genetics and reverse phenotyping. Hum Hered. 2004;58:131–8. doi: 10.1159/000083539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.West R, Miller P. What is the purpose of diagnosing addiction or dependence and what does this mean for establishing diagnostic criteria. Addiction. 2011;106:863–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03377.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kendell R, Jablensky A. Distinguishing between the validity and utility of psychiatric diagnoses. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:4–12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fiore M. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, Md: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2008. Tobacco Use and Dependence Guideline Panel. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin CS, Steinley DL, Verges A, Sher KJ. The proposed 2/11 symptom algorithm for DSM-5 substance use disorders is too lenient. Psychological Medicine. 2011:2008–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hughes JR. Should criteria for drug dependence differ across drugs? Addiction. 2006;101 (Suppl 1):134–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moolchan ET, Radzius A, Epstein DH, Uhl G, Gorelick DA, Cadet JL, Henningfield JE. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule: do they diagnose the same smokers? Addict behav. 2002;27:101–13. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mwenifumbo J, Tyndale RF. DSM-IV, ICD-10, and FTND: Discordant tobacco dependence diagnoses in adult smokers. J Addict Res Ther. 2010;1:105. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fidler JA, Shahab L, West R. Strength of urges to smoke as a measure of severity of cigarette dependence: Comparison with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence and its components. Addiction. 2011;106:631–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes JR, Baker TB, Breslau N, Covey L, Shiffman S. Applicability of DSM criteria to nicotine dependence. Addiction. 2011;106:894–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rose JS, Dierker LC. An item response theory analysis of nicotine dependence symptoms in recent onset adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:70–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes JR, Helzer JE, Lindberg SA. Prevalence of DSM/ICD-defined nicotine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;85:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sayette MA, Shiffman S, Tiffany ST, Niaura RS, Martin CS, Shadel WG. The measurement of drug craving. Addiction. 2000;95:S189–S210. doi: 10.1080/09652140050111762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miyata H, Yanagita T. Neurobiological mechanisms of nicotine craving. Alcohol. 2001;24:87–93. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(01)00144-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heinz A, Lober S, Georgi A, Wrase J, Hermann D, Rey ER, Wellek S, Mann K. Reward craving and withdrawal relief craving: Assessment of different motivational pathways to alcohol intake. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:35–9. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winters KC, Martin CS, Chung T. Substance use disorders in DSM-V when applied to adolescents. Addiction. 2011;106:882–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03334.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.