Abstract

Common to multiple vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, interventional restenosis, and transplant vasculopathy, is a localized inflammatory reaction. Activated vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) respond to local inflammation and migrate from the media into the lumen of the vessel where they proliferate and synthesize cytokines which they respond to in an autocrine fashion, sustaining the progression of the lesion. The deleterious effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines, particularly immunomodulatory interleukins, on vascular pathophysiology and development of these maladaptive processes have been the subject of intense study. Although a great deal of attention has been given to the negative effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines and interleukins, relatively little has been reported on the potentially beneficial paracrine and autocrine effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on the vascular response to injury. The vast majority of emphasis on secretion and function of anti-inflammatory mediators has been placed on leukocytes. Consequently, the role of non-immune cells, and direct effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on vascular cells is poorly understood. We will review the molecular mechanisms whereby anti-inflammatory interleukins inhibit signal transduction and gene expression in inflammatory cells. We will review studies in which beneficial “indirect” effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on progression of vascular disease are achieved by modulation of immune function. We will also present the limited studies in which “direct” effects of these interleukins on VSMC and endothelial cells dampen the vascular response to injury. We propose that expression of immunomodulatory cytokines by activated vasculature may represent an auto-regulatory feed back mechanism to promote resolution of the vascular response to injury.

Keywords: Atherosclerosis, restenosis, interleukin, smooth muscle cell, endothelial cell, NF-κB, inflammation

1. MANY VASCULAR DISEASES ARE INFLAMMATORY IN NATURE

1.1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is the leading cause of mortality in the western world, and is recognized as inflammatory in nature [1, 2]. This chronic inflammatory disease is characterized by infiltration of inflammatory cells in lesion-prone regions of the vasculature. The dynamic interaction of inflammatory and vascular cells, mediated by the cytokines elaborated by each cell type, leads to activation of signaling pathways, gene expression, and development of the obstructive or vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque. Despite recent advances, it has long been known that percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA), and more recently, stent placement, have limited long term efficacy as treatments for advanced coronary artery disease because of the high occurrence of vascular intimal hyperplasia observed in a significant number of patients undergoing these procedures [3, 4]. As part of the response to inflammation initiated by mechanical trauma, activated vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) migrate from the media into the lumen of the vessel where they proliferate and synthesize cytokines which they respond to in an autocrine fashion, sustaining the progression of intimal hyperplasia [4]. Similarly, the incidence of clinically significant Coronary Artery Transplant Vasculopathy [CAV], is approximately 40% at 3 years and is the major complication that limits long-term survival of cardiac and other solid organ transplantation [5]. Common to atherosclerosis, CAV and interventional restenosis is a localized inflammatory reaction in which injured endothelial cells (EC) secrete factors that recruit mononuclear cells which in turn secrete growth and inflammatory cytokines, including Interleukin-beta (IL-1β, Interferon gamma (IFNγ, basic Fibroblast Growth Factor (bFGF), and Platelet Derived Growth Factor (PDGF) [2]. This elicits activation of normally quiescent VSMC [3]. VSMC proliferation and matrix deposition are responsible for most of the obliterative arterial intimal thickening resulting from interventional procedures and transplant vasculopathy [5–7]. It has been suggested that the cytokine activation, matrix deposition, and proliferation of VSMC is the most critical cellular event in neointimal development [8, 9]. Thus, restenosis, atherosclerosis, and other vascular diseases are inflammatory in nature and rely on an immune system, but ultimately depend on VSMC as the effector cell leading to pathology. Accordingly, inflammatory cytokines, and their effects on inflammatory, endothelial, and VSMC activation events represent points of therapeutic intervention to attenuate many vascular obstructive and proliferative diseases.

1.2. Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins

The harmful effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα and IFNγ, on the vascular pathophysiology characteristic of atherosclerosis, interventional restenosis, and transplant vasculopathy have been the subject of intense study, and the subject of several excellent reviews [10–12]. Although cytokines such as TGFβ are known to have anti-inflammatory effects, the interleukins in particular are potent mediators of the inflammatory response in immune and vascular cells, and play a crucial role in propagation of atherosclerosis and other vascular inflammatory diseases [13]. As such, they will be the focus of this review. Importantly, interleukins and their receptors can also be synthesized by EC and VSMC. Interleukins can be classified into pro and anti-inflammatory effectors, based largely on their effects on leukocyte function. Pro-inflammatory interleukins induce a Th1, pro-inflammatory phenotype in lymphocytes, while anti-inflammatory interleukins induce a shift to a Th2 profile, with attenuation of pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and concomitant increase in anti-inflammatory cytokine expression.

For the purposes to focus this review, we will consider IL-4, IL-9 IL-10, IL-11, IL-13, and IL-19 to be anti-inflammatory interleukins (Table 1). Despite sharing receptor components with IL-2, Interleukin-4 (IL-4) promotes a Th2 response in lymphocytes [14]. IL-4 negatively regulates production of pro-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and T cells [14]. Although recognized as a T cell growth factor, IL-9 exerts a Th2 inflammatory response in these cells, and suppresses expression of TNFα, IFNγ, with a concurrent up regulation of IL-10 [15]. IL-9 is also implicated in playing a role in airway smooth muscle inflammation, and asthma [16]. Interleukin-10 [IL-10] is considered a prototypical anti-inflammatory cytokine, and is the most widely studied of the anti-inflammatory interleukins [17]. Its effector functions include a shift of T cell cytokine expression from a Th1 to a Th2 profile, and attenuation of the production of proinflammatory cytokines by macrophages [18]. Most of our information on mechanisms of anti-inflammatory interleukins originates from studies of IL-10. IL-10 has been promoted as a potential therapeutic modality for inflammatory diseases. IL-11 shares considerable sequence homology to the potent pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6, and even shares a common gp130 receptor subunit with IL-6 [19, 20]. However, despite these similarities, IL-11 does promote a T cell phenotypic switch from Th1 to Th2, and also down-regulates NF-κB activity in both immune and vascular cells. Il-11 also decreases expression of a wide-range of inflammatory cytokines in macrophages [19–21]. IL-13 shares 25% amino acid sequence homology with IL-4, but does not promote the Th2 phenotype in T cells [22]. However, IL-13 is a potent suppressor of expression of cytokines in monocytes and macrophages [23]. IL-19 is a recently described [2000] IL-10 family member and shares 20% amino acid identity to IL-10 [24]. Like IL-10, IL-19 also promotes an increase in Th2 to Th1 T lymphocyte ratios [25]. IL-19 can decrease expression of IFNγ, and increase expression of IL-4 in T lymphocytes [26]. The only pathology definitively associated with IL-19 at this time is the skin disease psoriasis [27].

Table 1.

Summary of Expression, Molecular Mechanisms, and Vascular Protective Effects of Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins. SMC, Smooth Muscle Cells; EC, Endothelial Cell; F, Fibroblast; T, T lymphocyte; B, Lymphocyte; M, Monocyte/Macrophage; N, Neutrophil; Baso, Basophils; E, Eosinophils; Mast, Mast Cells.

| Interleukin | Expressed in: | Effector Cell: | Anti-Inflammatory Mechanism | Reported Vascular Protective Effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | EC, T, B, Baso, E, Mast | M, N, A, F | Activates STAT6, induces SOCS-3, NF-κB inhibition, Inhibits p44/42 and p38 activation | No effects. Angogenic for EC | [33, 44, 47, 49, 52, 56,57, 59, 99] |

| IL-9 | T, B, M, Mast | T, SMC | STATS1, 3, and 5 activation and SOCS-3 induction, NF-κB Inhibition | Unknown | [34, 59] |

| IL-10 | T, B, M | M, T, N, F, B, Mast, SMC, A | Activates STAT1 and STAT3, Inhibits p44/42, p38, and NF-κB, induces SOCS-1 and 3 expression, de- creases Egr-1 activation, down regulates HuR activity | Protective, likely paracrine, with direct and indirect effects | [31, 32, 43, 47,48,49,52,54, 58,60,65,67] |

| IL-11 | SMC, EC | M, F, SMC | STAT1 and STAT3 Acivation, NF-κB inhibition | Unknown | [19,20,21, 36, 53, 55] |

| IL-13 | T | M, SMC, EC | Activates STAT6, induces SOCS-3, increase IκB, express BCL3 | Unknown. Angiogenic for EC | [35, 46, 58, 99, 103] |

| IL-19 | T, B, M, SMC | SMC | STAT1 and 3 activation, SOCS-5 Induction, p44/42 and p38 inhibition, and HuR inhibition | Protective, likely direct, autocrine | [37, 38, 71] |

Key: SMC, Smooth Muscle Cells; EC, Endothelial Cell; F, Fibroblast; T, T lymphocyte; B, Lymphocyte; M, Monocyte/Macrophage; N, Neutrophil; Baso, Basophils; E, Eosinophils; Mast, Mast Cells.

Although a great deal of attention has been given to the negative effects of pro-inflammatory interleukins in vascular disease, less has been described concerning the potential protective effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on the vascular response to injury [28]. An excellent review has considered the synthesis of pro-inflammatory immune modulators by VSMC [11]. Considering that vascular cells can synthesize many interleukins, it is surprising that very little has been reported concerning the direct, potential autocrine effects of these anti-inflammatory cytokines on the outcome of vascular inflammatory diseases. Taken a step further, this idea suggests that the inflamed vasculature can act as an efferent arm of the immune system. There is a limited, but important amount of literature indicating that vascular cells can also elaborate anti-inflammatory interleukins [28]. Taken together, this concept introduces the hypothesis of this review; that the injured vasculature may act in an autocrine fashion with beneficial effects on the vascular response to interventional restenosis, atherosclerosis, and transplant vasculopathy.

2. MOLECULAR MECHANISMS OF ANTI-INFLAMMATORY INTERLEUKINS

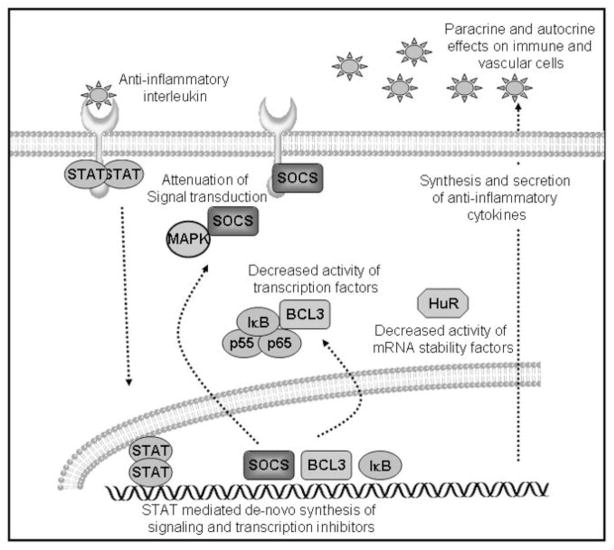

The processes of inhibition of cellular activation by anti-inflammatory cytokines are diverse, and the overwhelming majority of studies into their molecular mechanisms has been performed in immune cells. We will summarize pertinent data into three categories: modulation of signaling; modulation of transcription factors; and suppression of inflammatory gene expression. These are summarized in Fig. (1).

Fig. 1.

Cellular and molecular effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins. Interleukins activate STAT protein dimerization and translocation to the nucleus. STAT dimers mediate transcription of several signal transduction and transcription factor inhibitors. De novo synthesized SOCS proteins bind to receptors and signal transduction intermediates. IκB and BCL3 inhibit NF-κB activity. Decreased expression and activity of ARE-containing mRNA stability factors reduces expression of inflammatory and proliferation proteins. Synthesis and secretion of anti-inflammatory interleukins have autocrine and paracrine effects to reduce vascular injury and dampen local inflammation.

2.1. Signaling Cascades and Auto-Regulatory Loops Induced by Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins

The initial effector function of many interleukins are elaborated by activation of intracellular signaling cascades involving the JAK and STAT family of signaling proteins [29]. Tyrosine phosphorylated STATs dimerize and then translocate into the nucleus where they recognize specific DNA sequences or other transcription factors to influence target gene transcription [30]. The specificity of signaling between different interleukins often lies with differential, specific usage of “cytokine-specific” STAT proteins [31]. The signal transduction pathway utilized by the archetypal anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10 is representative of many anti-inflammatory interleukins. IL-10 activity requires STAT3, which transactivates multiple genes germane to regulation of the inflammatory response, and STAT3 is required for IL-10 attenuation of TNFα induced inflammatory events [31, 32]. Other anti-inflammatory cytokines utilize other STAT family signaling proteins as transcriptional activators or co-repressors. For example, in macrophages, IL-4 induces nuclear translocation of STAT6, which then competes with inflammation induced STAT-1 binding to promoter regions in inflammatory genes. In this instance, STAT-6 remains transcriptionally inactive, but rather, acts as a co-repressor to block STAT-1 activity [33]. In a murine T-lymphoma cell line, IL-9 induced rapid activation of STATs 1, 3, and 5 [34, 35]. Similarly, IL-13 activates STAT6, which interferes with STAT1 activation of NF-κB [35]. IL-11 can also activate STAT1 and STAT3 in adipocytes. However, rather than utilizing JAK activity, IL-11 activates these STATs via the PI3 kinase cascade, leading to suppression of cytokine synthesis by prevention of NF-κB activation [36]. Using a breast cancer cell line, it was found that IL-19 can induce STAT1 and STAT3 translocation to the nucleus [37]. More relevant to vascular biology, in human VSMC, IL-19 can also induce activation and translocation of STAT3 [38].

Negative regulation of cytokine-mediated activation of the JAK/STAT pathway has been shown to arise through several different mechanisms. One of these is by the action of the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) family proteins. These proteins are often synthesized de novo in response to cytokine stimulation and inhibit cytokine signaling by inhibition of JAK activity, or direct binding to cytokine receptors [39]. In many cases, transcriptional activation of SOCS genes are mediated by the STAT proteins [40, 41]. There are 6 SOCS family members which exert their inhibitory by at least two distinct mechanisms. Most of our information comes from studies of SOCS-1 through 3, which are inducible by IL-10. These proteins bind to tyrosine phosphorylated residues on signaling intermediates and receptor chains, resulting in an attenuation of signaling. SOCS proteins also target bound proteins for degradation via the E3 ubiquitin ligase pathway [42]. SOCS-3 in particular has been shown to inhibit signaling by IL-2 through 6, IFNγ, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. Much less is known about SOCS-4 through 6, though SOCS-5 is known to inhibit IL-6 signaling [42].

Since SOCS proteins are induced by STATs, a major function of the SOCS proteins are as an integral part of a classical autocrine negative feed-back and cross-talk inhibition of cytokine signaling. STAT mediated SOCS expression is a complex and tightly-regulated mechanism whereby anti-inflammatory cytokines exert their protective effects. Generally, SOCS-1 expression is utilized by Th1 cytokines, while SOCS-3 expression is induced by the Th2 anti-inflammatory cytokines. This is often not an all-or-nothing proposition. For example, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13 are known to induce expression of SOCS-1, 2, and 3. In situations where both pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines are used to co-stimulate a cell, SOCS-3 will co-repress the STAT mediated induction of SOCS-1 expression [43, 44]. For example, IL-9 can induce both SOCS-1 and 3, but only SOCS-3 inhibits signaling in an auto-feedback fashion [34]. Interestingly, in VSMC, IL-19 can induce SOCS5 expression, but not the other better characterized SOCS family proteins [38].

Anti-inflammatory cytokines have also evolved the capacity to diminish Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase [MAPK] signaling. p44/42 and p38 MAPK are important integrators of inflammation-inducible signaling, and both of these kinases have been shown to mediate macrophage, EC, and VSMC activation and contribute to the vascular response to injury [45,46]. In multiple cell types, IL-10 co-treatment can significantly reduce CD40-ligand and LPS induced activation of the MEK, p44/42 and p38 MAPK pathways [47, 48]. IL-4 can inhibit the p44/42 pathway in stimulated monocytes [47]. Inhibition of p38 MAPK is particularly relevant considering the central role p38 MAPK plays in integration of inflammatory signals, and both IL-4 and IL-10 can inhibit human neutrophil LPS-stimulated prostanoid synthesis by down-regulating the activation of p38 MAPK [49]. The mechanism[s] where by these interleukins inhibit these MAPKs are currently not known. One clue could come from investigation of IL-19. Pretreatment of VSMC with IL-19 results in a significant reduction in fetal calf stimulated p44/42 and p38 MAPK activation in cultured human VSMC [38]. It was found that this inhibition was mediated by SOCS5 interaction with these MAP kinases, suggesting that in other cell types, other interleukins could inhibit MAPKs by induction of SOCS proteins. Together, attenuation of signal transduction pathways by SOCS protein induction leading to MAPK inhibition is an effective strategy for reduction of inflammation by interleukins.

2.2. Modulation of Transcription Factor Activity and Effects on Gene Expression

A second mechanism whereby anti-inflammatory interleukins exert their effects is by modulation of NF-κB activity. The NF-κB complex is a cytoplasmic transcription factor consisting of 2 subunits (p50 and p65), and is activated by a number of intracellular pathways including stimulation of cytokine receptors, sheer stress, and oxidative processes [50]. NF-κB is present in the cytoplasm, where it exists in an inactive form. Upon stimulation with inflammatory factors, an inhibitory protein termed IκB disassociates from this complex and is proteolyticaly degraded, allowing the p50/p65 complex to translocate into the nucleus and act as a transcriptional activator. NF-κB is considered to be a “master switch” in transactivation of multiple genes involved in the inflammatory response, and relevant for vascular pathophysiology, including IL-8, IL-6, MCP-1 and ICAM-1 [50].

Inhibition of this important transcription factor is a potent strategy employed by several anti-inflammatory interleukins. For example, in activated macrophages, IL-11 inhibits TNFα and IL-12 production via inhibition of NF-κB translocation, and IL-4 and IL-10 can block NF-κB activation in response to IL-1β [52, 53]. Both IL-10 and IL-11 have been shown to inhibit VSMC proliferation [54, 55]. In both of these manuscripts, the authors propose that the observed growth inhibitory effects are due to inhibition of NF-κB and NF-κB-dependent inflammatory gene expression, including inhibition of IL-6 and IL-8. Modulation of IκB expression and stability is 1 of at least 2 mechanisms used to regulate NF-κB activity and decrease inflammatory gene transcription. IL-4 can negatively regulate NF-κB by increasing IκB transcription, leading to increased binding and inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation [56, 57]. Correspondingly, both IL-10 and IL-13 can also reduce or prevent IκB degradation [58]. Both IL-4 and IL-9 can increase the expression of BCL3, a protein with close homology to IκB, thus contributing to NF-κB inhibition [59]. A second mechanism is by increased degradation of NF-κB subunits themselves. In monocytes, IL-10 induction of SOCS-3, or over expression of SOCS3 inhibits NF-κB activity [60]. Since the stability of the p65 subunit of NF-κB is controlled by ubiquitin mediated proteolysis facilitated by SOCS-1, this links these 2 important pathways, and implicates the NF-κB pathway as another target of the SOCS auto regulatory feed back inhibition loop [61].

IL-10 can target other transcription factors as well. Early growth response factor-1 (Egr-1) is an immediate-early growth factor responsive transcription factor induced in vascular cells by to arterial injury [62, 63]. Egr-1 mRNA is not expressed in uninjured tissue or unactivated cells, but is rapidly induced by several extracellular stimuli, including mechanical trauma, sheer stress, inflammatory cytokines, and hypoxia. Egr-1 transactivates many genes associated with cell cycle progression and proliferation [64]. IL-10 can significantly decrease Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) stimulated Egr-1 activation in macrophages, indicating a more direct link to inhibition of proliferation [65].

2.3. Regulation of Gene Expression and mRNA Stability

While many cytokines, particularly IL-1β, and TNFα have been shown to stabilize inflammatory gene transcripts, very few soluble factors have been shown to destabilize mRNA. A third global mechanism whereby anti-inflammatory interleukins can potentially dampen the inflammatory response is by inhibition of expression and/or post-transcriptional processing of inflammatory proteins. This inhibition is often accomplished by a destabilization of mRNA transcripts mediated by mRNA-binding stability factors [66]. The 3′ UTR of many transcripts associated with inflammation contain AU-rich elements (ARE) which are target sites for these mRNA-binding stability factors [66]. This control of mRNA stability allows cells to tightly regulate the expression of factors which have potent effects on the health of the host organism. Examples of relevant transcripts which contain this regulatory sequence include, but are not limited to oncogenes, TNFα, IL-8, cyclin B, c-fos, ICAM-1, and VEGF. An extensive list can be found at the website: http://rc.kfshrc.edu.sa/ared/.

Studies in transgenic mice suggest that up regulation of one of these mRNA stability factors, HuR, can support hyper activation of inflammatory mediators to exacerbate inflammation [66,67]. One manuscript describes the down-regulation of HuR by IL-10 in monocytes [67], and attributes this as a major mechanism whereby IL-10 exerts systemic anti-inflammatory effects. Information regarding HuR expression and function in vascular biology are limited to 3 manuscripts. One suggests that HuR could account for down-regulation of guanylyl cyclase genes in hypertensive (SHR) rats [68], and a second manuscript indicates that LPS induces expression of HuR in VSMC [69]. A third, very interesting manuscript shows that enhanced proliferation of cultured hVSMC is linked to increases in HuR activity [70]. This work also indicates that HuR expression is increased in proliferative vascular pathologies. Recent studies suggest that IL-19 can decrease HuR expression in human VSMC, with a subsequent decrease in the stability of inflammatory transcripts in these cells [71].

In terms of outcome, and mechanism of effects, an interesting and pertinent analogy can be made between anti-inflammatory interleukins and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Originally designed to target hepatocytes and reduce endogenous cholesterol synthesis, HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, or statins, can also act on endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes, with direct and indirect vascular benefits by attenuation of inflammation. Interference of the mevalonate pathway depresses signal transduction pathways by prevention of the synthesis of iso-prenoid intermediates, which play an important role in the post-translational modification of the small GTPases Rho, Rac and Ras, which act as molecular switches upstream of inflammatory signal transduction pathways [73]. Several studies demonstrate that statins can inhibit MAPKs, including p44/42 and p38, and can directly modulate inflammatory gene expression by diminishing activity of NF-κB [74, 75]. In macrophages, statins are able to induce expression of SOCS-3, and decrease inflammatory cytokine induced signal transduction [74]. In T cells, statins can also induce the release of Th2 promoting cytokines, including IL-10, and diminish secretion of Th1 cytokines such as IL-2 [75, 76]. These parallels between anti-inflammatory interleukins and anti-inflammatory effects of statins points to these proteins as fundamental components of anti-inflammatory pathways, and implicates them as targets for anti-inflammatory therapeutics.

3. EFFECTS OF ANTI-INFLAMMATORY CYTOKINES ON VASCULAR RESPONSE TO INJURY

3.1. Beneficial, but “Indirect” Effects of Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins on Progression of Vascular Disease

An impressive amount of literature exists concerning the potential protective effects of anti-inflammatory interleukins on the vascular response to injury. The overwhelming amount of this literature suggests that the effects on reduction of vascular injury attributed to many of these soluble factors are a paracrine effect mediated by modulation of immune function. This is likely by alteration of the T lymphocyte Th2/Th1 ratio toward a more anti-inflammatory phenotype, with subsequent changes in serum inflammatory cytokine levels. The experimental approach of many of these studies has been to mechanically injure or feed a high-fat diet to an interleukin knock out or transgenic mouse. While a sound approach, it is somewhat limited, in that if every cell in the mouse has been modified, including immune and vascular, it cannot be determined if the observed vascular response to injury originates from the vascular cells, or is a secondary result from a diminution of the inflammatory response. Use of conditional, tissue specific knock out or transgenic mice should clarify this important limitation. The other general approach has been either a systemic infusion of interleukin, or adenovirus encoding this interleukin into the host animal, and assessment of a response to injury or high-fat diet. Again, a limitation with this approach is that it cannot be determined if these anti-inflammatory cytokines suppress vascular cell function, for example, VSMC migration and proliferation, or inflammatory cell function, with a systemic dampening of the host immune response and subsequent reduction in vascular injury.

The majority of these studies focus on IL-10 in the context of atherosclerosis. IL-10 is expressed In human atherosclerotic plaque, and it was found that increased IL-10 serum levels are associated with improved systemic endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease [72, 77]. IL-10 knock out and transgenic mice have been developed, and generally show that increased IL-10 is protective, and absence of IL-10 is deleterious to the vascular response to insult. In two studies it was found that IL-10-deficient mice fed an atherogenic diet exhibit a significant increase in lipid accumulation and demonstrate increased lesions compared with wild-type mice [78, 79]. In one of these studies, restoration of IL-10 by intramuscular electrotransfer of plasmid encoding IL-10 cDNA caused a 60% reduction in lesion size [78]. In another study, IL-10 deficient mice were crossed with the atherosclerosis-susceptible Apolipoprotein E−/− mouse [80]. It was interesting in that not only was the early phase of lesion development increased, but proteolytic and procoagulant activity was elevated in advanced lesions, suggesting that at least in this model, IL-10 may not only reduce atherogenesis, but also improve the stability of plaques. Mechanistic support for this comes from ex vivo studies in cultured monocytes, where IL-10 decreases MMP-9 and increases TIMP-1 levels, both at the transcriptional level [81]. In a similar study taking the constitutive over expression approach, atherogenesis is decreased in IL-10 transgenic mice fed a high-fat diet [82]. Support for the protective effects of systemic IL-10 over expression come from the observation that injection of low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) knockout mice with recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2 [AAV]/interleukin-10 virus via tail vein injection resulted in a significant reduction in atherogenesis [83]. Similar results were observed in Apolipoprotein E-knockout (ApoE-KO) mice in which IL-10 over expression was achieved by plasmid expressing IL-10 [84]. In this study, not only was plaque area reduced, but Th1 lymphocyte infiltrate in the plaque was decreased as well. Intramuscular injection of AAV5-mIL10 into ApoE-deficient, atherosclerosis-susceptible mice inhibit atherogenesis through both anti-inflammatory and cholesterol-lowering effects [85, 86]. One anti-inflammatory effect is a decrease in MCP-1 expression and serum concentrations, likely via inhibition of NF-κB activity. The means of how IL-10 reduces cholesterol levels in these mice has not been clarified. However, one potential mechanism for these effects, which again point to immune cells as the primary effector cell is that IL-10 can redirect macrophage cholesterol handling towards reverse cholesterol transport, which contributes to its anti-atherosclerotic action [87].

It is unclear whether vascular protection by anti-inflammatory interleukins is limited to atherosclerosis, or participates in other types of vascular injury. For instance, in IL-10−/− mice ligation-injured carotid arteries which received intraperitoneal administration of IL-10 showed no protection in development of intimal hyperplasia compared with wild-type controls, or IL−/− mice receiving saline. [88]. On the other hand, exogenous IL-10 administration to wire carotid injured WT mice did show protective effects with attenuation of intimal hyperplasia, consistent with decreased expression of NF-κB, MCP-1, and bFGF [89]. In an animal study which more closely resembles the human clinical scenario, hypercholesterolemic rabbits were treated with recombinant human IL-10 [rhuIL-10] for 3 days after balloon angioplasty or 28 days after stent implantation. Morphometric analyses indicated that rhuIL-10 reduced intimal growth by approximately 50% after balloon angioplasty or stenting, with a corresponding reduction in macrophage infiltration in the intima and the media of injured arteries [90]. Perhaps 1 reason for the difference in outcome of these 2 studies is that injury to the ligated arteries was performed without the background of increased lipid-induced inflammation.

Evidence that these vascular protective effects are likely indirect and mediated by immune cells comes from several studies. In an interesting series of experiments, transfer of bone marrow from IL-10 transgenic mice to wild type and LDL receptor−/− mice inhibits atherosclerosis by altering the phenotype of the resident lymphocyte and macrophage populations in the atherosclerotic plaque [91]. Similarly, in bone-marrow transplanted LDL receptor−/− mice, IL-10 expressed by leukocytes prevents exaggerated advanced atherosclerosis development and plays a critical role in reduction of cellular and collagen plaque composition, at least in part, through a modulation of the systemic immune response [91].

Information regarding other anti-inflammatory cytokines is sparse and somewhat conflicting. Deficiency of IL-4 did not reduce or increase protection from early atherosclerosis in the IL-4 null mouse as compared to their WT littermates [92]. Correspondingly, exogenous administration of IL-4 does not significantly influence the development of athero-sclerotic lesions in susceptible ApoE−/− or LDL receptor−/− mice, irrespective of the mode of induction of atherosclerosis [93]. Further, and somewhat counter-intuitive for what one would expect for an anti-inflammatory interleukin, ApoE−/− mice crossed with IL-4−/− mice had a 27% reduction in plaque area compared to ApoE−/− mice at 30 weeks of age [94]. There are also disparate results in ex vivo approaches with other anti-inflammatory interleukins as well. While several studies in cultured cells demonstrate convincingly that IL-11 has anti-inflammatory effects on leukocyte function, including inhibition of TNFα, IL-1β, and IFNγ synthesis, no in vivo studies have been reported regarding the ability of this cytokine to influence the vascular response to atherosclerosis or mechanical injury. In vivo, IL-9 can confer resistance to septic shock in mice [95]. In this study, the protective effect of IL-9 was correlated with marked decreases in the production of the inflammatory mediators TNFα, IL-12, and IFNγ, as well as the induction of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. However, the role of IL-9, or IL-13 in protection against atherosclerosis or interventional restenosis has not been reported.

3.2. Beneficial, “Direct” Effects of Anti-Inflammatory Interleukins on Progression of Vascular Disease

Understandably, most of the emphasis on secretion and function of inflammatory mediators has been placed on leukocytes, and the direct molecular effects of these interleukins on function of vascular cells are incompletely understood. Moreover, the potential of activated EC and VSMC to endogenously express anti-inflammatory cytokines and respond to them in an autocrine fashion has not been fully explored. We will first discuss paracrine effectors; anti-inflammatory interleukins which are not produced by vascular cells but do have profound suppressive effects on their activation. We will then discuss anti-inflammatory interleukins produced by vascular cells.

Paracrine Effects

The expression of IL-10 by VSMC or EC has not been reported, however, the addition of IL-10 to cultured VSMC has been to shown to have potent anti-proliferative effects. These growth inhibitory effects are attributed by an IL-10 mediated suppression of NF-κB activity, with subsequent reduction in inflammatory gene expression [55]. In this study, IL-10 reduced IκB degradation, suggesting that IL-10 also interferes with signaling pathways leading to phosphorylation of this regulatory protein. In vivo, systemic infusion of IL-10 does reduce SMC proliferation and intimal hyperplasia in response to injury; however, it is difficult to distinguish the contribution of inflammatory cell attenuation from a direct inhibitory effect on VSMC activation and reduction of intimal hyperplasia [90, 78]. Information on the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-4 is conflicting. IL-4 is detected in EC from atherosclerotic plaques, but not VSMC [96]. While IL-4 can inhibit proliferation of cultured human SMC [97], and IL-4 can weakly reduce FCS induced Cyclin D1 mRNA and protein and CDK2 mRNA expression in these cells [98], opposite effects are shown in endothelial cells. In endothelial cells IL-4 acts to increase VCAM-1 mRNA stability and VCAM-1 gene transcription in a time- and dose-dependent manner via SP-1 transcription factor activation [99,100]. IL-4 can also up-regulate the expression of MCP-1 and decrease nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability through activation of NADPH oxidase in endothelial cells. Further, IL-4 can increase mRNA and protein secretion of other inflammatory markers in EC, such as VCAM-1, E-selectin, and IL-6 [101]. Together, these results are in favor of a pro-inflammatory and pro-atherogenic effect of IL-4 in endothelium [102]. Interestingly, both IL-4 and IL-13 induce migration and formation of tube-like structures in human EC, consistent with angiogenesis [103]. While IL-4 can induce expression of both pro and anti-inflammatory genes in cultured human EC [101], IL-4 does offer EC protection for porcine EC against apoptosis induced by TNFα plus cyclo-hexamide [101]. The mechanisms of IL-4 induction of inflammatory gene transcription are currently uncharacterized. IL-13 also has seemly contradictory effects. While in monocytes, IL-13 attenuates expression of a host of inflammatory cytokines, IL-13 increased expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines MCP-1 and IL-8 in TNFα challenged VSMC [105]. IL-13 also suppressed NO production in VSMC [106].

Autocrine Effects

With chronic exposure to multiple inflammatory factors, the dedifferentiated “myleofibroblastic” VSMC can synthesize many cytokines ascribed to be restricted to inflammatory cells [107, 108]. This promotes the concept of positive autocrine feedback in which the injured vascular cell can synthesize factors which not only attenuate their own mal-adaptive activation, but also dampen the local inflammatory response. Inflammatory cytokines IL-1α, TGFβ, and TNFα can induce IL-11 gene expression in cultured VSMC [108]. IL-11 is similar to IL-10 in that in VSMC, it has direct anti-proliferative effects which are also mediated by inhibition of NF-κB activity [55]. IL-11 does have a direct anti-apoptotic effect on endothelial cells, mediated by the induction of survivin, a protein with known inhibitory effects on apoptosis [110]. IL-9 is expressed in airway SMC, but its expression in VSMC or EC has not been reported [16]. In airway SMC, IL-9 can induce expression of the Th2 related cytokine CCL11, but yet increased the severity of asthma in IL-9 transgenic mice [111]. A role for this anti-inflammatory interleukin, along with IL-13, in terms of expression and direct effects on vascular cells has yet to be elucidated.

Basal levels of IL-19 can be detected in human monocytes, B, and T lymphocytes which can be upregulated by LPS, G-CSF, IL-4 and IL-13 stimulation [112]. However, 1 recent manuscript indicates IL-19 is not expressed in quiescent VSMC or normal arteries, but can be induced in cultured VSMC by inflammatory cytokines, and in arteries by injury [38]. IL-19 is anti-proliferative for cultured human coronary artery VSMC. This may be due to the observation that IL-19 transiently reduces HuR expression, which is known to play a role in VSMC proliferation [71]. IL-19 reduces activation of p38 and p44/42 MAPK, and induces rapid, transient expression of SOCS5, which interacts with both of these MAP kinases, presumably to inactivate or degrade them [38]. Notably, IL-19 adenoviral gene transfer significantly reduces neointimal hyperplasia and proliferation of medial and intimal VSMC in balloon angioplasty-injured rat carotid arteries [38]. Together, these data suggest that IL-19 expression by injured arteries, particularly VSMC, may constitute a novel autocrine regulatory feed-back to limit the VSMC response to injury.

4. SUMMARY AND PERSPECTIVES

The deleterious effects of pro-inflammatory cytokines on development of many vascular diseases has been well documented. However, a gap in our knowledge exists on the role of anti-inflammatory interleukins in vascular biology, particularly with respect to direct suppressive effects on vascular wall cells. While it is clear that anti-inflammatory inter-leukins have protective effects on atherosclerosis, and to a lesser extent, interventional restenosis, it is unclear whether this is do to a dampening of the inflammatory response, or suppression of vascular cell activation. Utilization of conditional, tissue-specific knock out or transgenic animals may help to delineate the contribution of each of these cell types as the major effector cell. It is also likely that paracrine communication between vascular and immune cells is bidirectional, and perhaps equally likely that activated vascular cells can elaborate immunomodulatory cytokines that can influence the function of immune cells. In effect, the activated vasculature can act as an efferent arm of the immune system. Thus, expression of anti-inflammatory interleukins by activated vascular cells may represent a negative auto-regulatory feed back mechanism to promote resolution of the vascular response to injury by two broad mechanisms; the first is a direct suppression of EC and/or VSMC activation, and the second is the intriguing possibility that the inflamed vasculature may modulate the local inflammatory response of immune cells, also with beneficial protective effects on the vascular response to injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant HL-63810 from the National Heart Lung, and Blood Institute, and grant 0455562U from the American Heart Association, and Grant 146643428 from the Roche Organ Transplant Research Foundation, to MVA.

References

- 1.Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature. 2002;420:868–74. doi: 10.1038/nature01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Welt FGP, Rogers C. Inflammation and restenosis in the stent era. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1769–76. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000037100.44766.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–9. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ventura HO, Mehra MR, Smart FW. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: Current concepts. Am Heart J. 1995;129:791–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(95)90331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Libby P, Salomon R, Payne D, Schoen F, Pober J. Functions of vascular wall cells related to development of Transplantation-associated coronary arteriosclerosis. Transplant Proc. 1989;6:3677–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnhart G, Pascoe E, Mills S. Accelerated coronary arteriosclerosis in cardiac transplant recipients. Transplant Rev. 1987;1:31–46. doi: 10.1016/s0955-470x(87)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.IPJ, Fuster V, Badimon L, Badimon J, Taubman M, Chesebro J. Syndromes of Accelerated Atherosclerosis: Role of Vascular Injury and Smooth Muscle Cell Proliferation. J Am Coll Cardiology. 1990;15:1667–87. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)92845-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz R, Murphy J, Edwards W, Camrud A, Vlietstra R, Holmes D. Restenosis after balloon angioplasty: a practical proliferative model in porcine coronary arteries. Circulation. 1990;82:2190–200. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raines E, Ferri N. Cytokines affecting endothelial and smooth muscle cells in vascular disease. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1081–92. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500004-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Singer C, Sonemany S, Baker K, Gerthoffer W. Synthesis of immune modulators by smooth muscles. BioEssays. 2004;26:646–55. doi: 10.1002/bies.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Von der Thüsen J, Kuiper J, van Berkel T, Biessen E. Interleukins in atherosclerosis: molecular pathways and therapeutic potential. Pharmacol Rev. 2003;55:133–66. doi: 10.1124/pr.55.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kleemann R, Zadelaar S, Kooistra T. Cytokines and atherosclerosis: a comprehensive review of studies in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79:360–76. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paul W. Interleukin 4: a protypic immunoregulatory lymphokine. Blood. 1991;77:1859–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Godfraind C, Louahed J, Faulkner H, Vink A, Warnier G, Grencis R, et al. Intraepithelial infiltration by mast cells with both connective tissue-type and mucosal-type characteristics in gut, trachea, and kidneys of IL-9 transgenic mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:3989–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gounni A, Hamid Q, Rahman S, Hoeck J, Yang J, Shan L. IL-9-mediated induction of eotaxin1/CCL11 in human airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2771–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Waal Malefyt R, Yssel H, Roncarolo M, Spits H, de Vries J. Interleukin-10. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4:314–20. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(92)90082-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Der Thusen J, Kuiper J, Fekkes M, De Vos P, Van Berkel T, Biessen E. Attenuation of atherogenesis by systemic and local adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of interleukin-10 in LDLr−/− mice. FASEB J. 2001;15:2730–2. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0483fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schwertschlag U, Trepicchio W, Dykstra K, Keith J, Turner K, Dorner A. Hematopoietic, immunomodulatory and epithelial effects of interleukin-11. Leukemia. 1999;13:1307–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trepicchio W, Dorner A. Interleukin-11. A gp130 cytokine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;29:12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trepicchio W, Bozza M, Pedneault G, Dorner A. Recombinant human IL-11 attenuates the inflammatory response through down-regulation of proinflammatory cytokine release and nitric oxide production. J Immunol. 1996;157:3627–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zurawski G, de Vries J. Interleukin 13, an interleukin 4-like cytokine that acts on monocytes and B cells, but not on T cells. Immunol Today. 1994;15:19–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Waal Malefyt R, Figdor C, Huijbens R, Mohan-Peterson S, Bennett B, Culpepper J, et al. Effects of IL-13 on phenotype, cytokine production, and cytotoxic function of human monocytes. Comparison with IL-4 and modulation by IFN-gamma or IL-10. J Immunol. 1993;151:6370–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallagher G, Dickensheets H, Eskdale J, Izotova L, Mirochnitchenko O, Peat J, et al. Cloning, expression and initial characterization of interleukin-19 (IL-19), a novel homologue of human interleukin-10 (IL-10) Genes Immun. 2000;1:442–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallagher G, Eskdale E, Jordan W, Peat J, Campbell J, Boniotto M, et al. Human interleukin-19 and its receptor: a potential role in the induction of Th2 responses. Int Immunopharmacol. 2004;4:615–26. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jordan W, Eskdale J, Boniotto M, Lennon G, Peat J, Campbell JDM, et al. Human IL-19 regulates immunity through auto- induction of IL-19 and production of IL-10. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:1576–82. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sa S, Valdez P, Wu J, Jung K, Zhong F, Hall L, et al. The effects of IL-20 subfamily cytokines on reconstituted human epidermis suggest potential roles in cutaneous innate defense and pathogenic adaptive immunity in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2007;178:2229–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Anti-Inflammatory mechanisms in the vascular wall. Circulation Res. 2001;88:877–87. doi: 10.1161/hh0901.090440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paukku K, Silvennoinen O. STATs as critical mediators of signal transduction and transcription: lessons learned from STAT5. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2004;15:435–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Darnell J., Jr STATs and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–5. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murray P. STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory signalling. Biochem Socy Trans. 2006;34:1028–31. doi: 10.1042/BST0341028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qing M, Nimmesgern A, Heinrich P, Schumacher K, Vazquez-Jimenez J, Hess J, et al. Intrahepatic synthesis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha related to cardiac surgery is inhibited by interleukin-10 via the Janus kinase (Jak)/signal transducers and activator of transcription (STAT) pathway. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2769–75. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098858.64868.9C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamilton T, Ohmori Y, Tebo J, Kishore R. Regulation of macrophage gene expression by pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. Pathobiology. 1999;67:241–4. doi: 10.1159/000028101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lejeune D, Demoulin J, Renauld J. Interleukin 9 induces expression of three cytokine signal inhibitors: cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein, suppressor of cytokine signalling (SOCS)-2 and SOCS-3, but only SOCS-3 overexpression suppresses interleukin 9 signalling. Biochem J. 2001;353(Pt 1):109–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albanesi C, Fairchild H, Madonna S, Scarponi C, De Pità O, Leung D, et al. IL-4 and IL-13 negatively regulate TNF-alpha- and IFN-gamma-induced beta-defensin expression through STAT-6, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1, and SOCS-3. J Immunol. 2007;179:984–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tenney R, Stansfield K, Pekala P. Interleukin 11 signaling in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:160–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parrish-Novak J, Xu W, Brender T, Yao L, Jones C, West J, et al. Interleukins 19, 20, and 24 signal through two distinct receptor complexes. Differences in receptor-ligand interactions mediate unique biological function. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47517–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian Y, Sommerville L, Cuneo A, Kelemen S, Autieri M. Expression and Suppressive Effects of Interleukin-19 on Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Pathophysiology and Development of Intimal Hyperplasia. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:901–9. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooney R. Suppressors of Cytokine Signaling (SOCS): Inhibitors of the JAK/STAT Pathway. Shock. 2002;17:83–90. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davey H, McLachlan M, Wilkins R, Hilton D, Adams T. STAT5b mediates the GH-induced expression of SOCS-2 and SOCS-3 mRNA in the liver. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;158:111–6. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(99)00175-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen X, Losman J, Rothman P. SOCS proteins, regulators of intracellular signaling. Immunity. 2000;13:287–90. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujimoto M, Naka T. Regulation of cytokine signaling by SOCS family molecules. Trends in Immunology. 2003;24:659–66. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ding Y, Chen D, Tarcsafalvi A, Su R, Qin L, Bromberg J. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 inhibits IL-10-mediated immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:1383–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Albanesi C, Fairchild H, Madonna S, Scarponi C, De Pità O, Leung D, et al. IL-4 and IL-13 negatively regulate TNF-alpha- and IFN-gamma-induced beta-defensin expression through STAT-6, suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS)-1, and SOCS-3. J Immunol. 2007;179:984–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim S, Izumi Y, Yano M, Hamaguchi A, Miura K, Yamanaka A, et al. Angiotensin blockade inhibits activation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases in rat balloon-injured artery. Circulation. 1998;97:1731–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.17.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohashi N, Matsumori A, Furukawa Y, Ono K, Okada M, Iwasaki A, et al. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in neointimal hyperplasia after vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2521–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.12.2521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue Y, Otsuka T, Niiro H, Nagano S, Arinobu Y, Ogami E, et al. Novel regulatory mechanisms of CD40-induced prostanoid synthesis by IL-4 and IL-10 in human monocytes. J Immunol. 2004;172:2147–54. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward C, Murray J, Clugston A, Dransfield I, Haslett C, Rossi A. Interleukin-10 inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced survival and extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation in human neutrophils. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:2728–37. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagano S, Otsuka T, Niiro H, Yamaoka K, Arinobu Y, Ogami E, et al. Molecular mechanisms of lipopolysaccharide-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human neutrophils: involvement of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and regulation by anti-inflammatory cytokines. Int Immunol. 2002;14:733–40. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Collins T. Endothelial nuclear factor-kappa B and the initiation of the atherosclerotic lesion. Lab Invest. 1993;68:499–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hanada T, Yoshimura A. Regulation of cytokine signaling and inflammation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:413–21. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pousset F, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Parnet P. Interleukin-1 signaling in mouse astrocytes involves Akt: a study with interleukin-4 and IL-10. Eur Cytokine Net. 2000;11:427–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trepicchio W, Dorner A. Interleukin-11. A gp130 cytokine. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;856:12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazighi M, Pelle A, Gonzalez W, Mtairag el M, Philippe M, Henin D, et al. IL-10 inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell activation in vitro and in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H866–71. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00918.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zimmerman M, Selzman C, Reznikov L, Raeburn C, Barsness K, McIntyre R, Jr, et al. Interleukin-11 attenuates human vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:75–80. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00987.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Donnelly R, Crofford L, Freeman S, Buras J, Remmers E, Wilder R, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of IL-6 production by IL-4. Differential effects of IL-4 on nuclear factor-kappa B activity in monocytes and fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1993;151:5603–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abu-Amer Y. IL-4 abrogates osteoclastogenesis through STAT6-dependent inhibition of NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1375–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI10530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lentsch A, Shanley T, Sarma V, Ward P. In vivo suppression of NF-kappa B and preservation of I kappa B alpha by interleukin-10 and interleukin-13. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2443–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Richard M, Louahed J, Demoulin J, Renauld J. Interleukin-9 regulates NF-kappaB activity through BCL3 gene induction. Blood. 1999;93:4318–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park S, Kim K, Hwang H, Kim T. Regulatory effect of SOCS on NF-kappaB activity in murine monocytes/macrophages. DNA Cell Biol. 2003;22:131–9. doi: 10.1089/104454903321515931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ryo A, Suizu F, Yoshida Y, Perrem K, Liou Y, Wulf G, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1413–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khachigian L, Lindner V, Williams A, Collins T. Egr-1-induced endothelial gene expression: A common theme in vascular injury. Science. 1996;271:1427–31. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5254.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khachigian L, Collins T. Inducible expression of Egr-1-dependent genes. a paradigm of transcriptional activation in vascular endothelium. Circ Res. 1997;81:457–61. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Thiel G, Cibelli G. Regulation of life and death by the zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1. J Cell Physiol. 2002;193:287–92. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamimura M, Viedt C, Dalpke A, Rosenfeld M, Mackman N, Cohen D, et al. Interleukin-10 suppresses tissue factor expression in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages via inhibition of Egr-1 and a serum response element/MEK-ERK1/2 pathway. Circ Res. 2005;97:305–13. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000177893.24574.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katsanou V, Papadaki O, Milatos S, Blackshear P, Anderson P, Kollias G, et al. HuR as a negative posttranscriptional modulator in inflammation. Mol Cell. 2005;19:777–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajasingh J, Bord E, Luedemann C, Asai J, Hamada H, Thorne T, et al. IL-10-induced TNF-alpha mRNA destabilization is mediated via IL-10 suppression of p38 MAP kinase activation and inhibition of HuR expression. FASEB J. 2006;20:2112–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6084fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kloss S, Rodenbach D, Bordel R, Mulsch A. Human-antigen R (HuR) expression in hypertension: downregulation of the mRNA stabilizing protein HuR in genetic hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;45:1200–6. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000165674.58470.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lin FY, Chen YH, Lin YW, Tsai JS, Chen JW, Wang HJ, et al. The role of human antigen R, an RNA-binding protein, in mediating the stabilization of toll-like receptor 4 mRNA induced by endo-toxin: a novel mechanism involved in vascular inflammation. Arte-rioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:2622–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000246779.78003.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pullmann R, Jr, Juhaszova M, Lopez de Silanes I, Kawai T, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Halushka M, et al. Enhanced proliferation of cultured human vascular smooth muscle cells linked to increased function of RNA-binding protein HuR. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22819–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501106200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cuneo A, Autieri M. The anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-19 suppresses VSMC activation by attenuation of proliferative and inflammatory gene expression (Abstract) FASEB J. 2008;22:900–6. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mallat Z, Heymes C, Ohan J, Faggin E, Lesèche G, Tedgui A. Expression of interleukin-10 in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: relation to inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and cell death. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:611–6. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang CY, Liu PY, Liao JK. Pleotropic effects of statin therapy: molecular mechanisms and clinical results. Trends Mol Med. 2007;14:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Huang KC, Chen CW, Chen JC, Lin WW. Statins induce suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in macrophages. FEBS Lett. 2003;555:385–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01297-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dunn SE, Youssef S, Goldstein MJ, Prod’homme T, Weber MS, Zamvil SS, et al. Isoprenoids determine Th1/Th2 fate in pathogenic T cells, providing a mechanism of modulation of autoimmunity by atorvastatin. J Exp Med. 2006;203:401–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Youssef S, Stüve O, Patarroyo JC, Ruiz PJ, Radosevich JL, Hur EM, et al. The HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, atorvastatin, promotes a Th2 bias and reverses paralysis in central nervous system autoimmune. Nature. 2002;420:78–84. doi: 10.1038/nature01158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fichtlscherer S, Breuer S, Heeschen C, Dimmeler S, Zeiher AM. Interleukin-10 serum levels and systemic endothelial vasoreactivity in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:44–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mallat Z, Besnard S, Duriez M, Deleuze V, Emmanuel F, Bureau MF, et al. Protective role of interleukin-10 in atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 1999;85:e17–24. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.8.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinderski Oslund L, Hedrick C, Olvera T, Hagenbaugh A, Territo M, Berliner J, et al. Interleukin-10 blocks atherosclerotic events in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999;19:2847–53. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.12.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Caligiuri G, Rudling M, Ollivier V, Jacob M, Michel J, Hansson G, et al. Interleukin-10 deficiency increases atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and low-density lipoproteins in apolipoprotein E knockout mice. Mol Med. 2003;9:10–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mostafa Mtairag E, Chollet-Martin S, Oudghiri M, Laquay N, Jacob M, Michel J, et al. Effects of interleukin-10 on monocyte/endothelial cell adhesion and MMP-9/TIMP-1 secretion. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:882–90. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00287-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pinderski L, Fischbein M, Subbanagounder G, Fishbein M, Kubo N, Cheroutre H, et al. Overexpression of interleukin-10 by activated T lymphocytes inhibits atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient Mice by altering lymphocyte and macrophage phenotypes. Circ Res. 2002;90:1064–71. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000018941.10726.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Liu Y, Li D, Chen J, Xie J, Bandyopadhyay S, Zhang D, Nemarkommula, et al. Inhibition of atherogenesis in LDLR knockout mice by systemic delivery of adeno-associated virus type 2-hIL-10. Atherosclerosis. 2006;188:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Namiki M, Kawashima S, Yamashita T, Ozaki M, Sakoda T, Inoue N, et al. Intramuscular gene transfer of interleukin-10 cDNA reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Atherosclerosis. 2004;172:21–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yoshioka T, Okada T, Maeda Y, Ikeda U, Shimpo M, Nomoto T, et al. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated interleukin-10 gene transfer inhibits atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1772–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Eefting D, Schepers A, De Vries MR, Pires NM, Grimbergen JM, Lagerweij T, et al. The effect of interleukin-10 knock-out and overexpression on neointima formation in hypercholesterolemic APOE*3-Leiden mice. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:335–42. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubic T, Lorenz RL. Downregulated CD36 and oxLDL uptake and stimulated ABCA1/G1 and cholesterol efflux as anti-atherosclerotic mechanisms of interleukin-10. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:527–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rectenwald JE, Minter RM, Moldawer LL, Abouhamze Z, La Face D, Hutchins E, et al. Interleukin-10 fails to modulate low shear stress-induced neointimal hyperplasia. J Surg Res. 2002;102:110–8. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zimmerman M, Reznikov L, Raeburn C, Selzman C. Interleukin-10 attenuates the response to vascular injury. J Surg Res. 2004;121:206–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Feldman L, Aguirre L, Ziol M, Bridou J, Nevo N, Michel J, et al. Interleukin-10 inhibits intimal hyperplasia after angioplasty or stent implantation in hypercholesterolemic rabbits. Circulation. 2000;101:908–16. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Potteaux S, Esposito B, van Oostrom O, Brun V, Ardouin P, Groux H, et al. Leukocyte-derived interleukin 10 is required for protection against atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1474–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000134378.86443.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.George J, Mulkins M, Shaish A, Casey S, Schatzman R, Sigal E, et al. Interleukin (IL)-4 deficiency does not influence fatty streak formation in C57BL/6 mice. Atherosclerosis. 2000;153:403–11. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00418-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.King V, Cassis L, Daugherty A. Interleukin-4 does not influence development of hypercholesterolemia or angiotensin II-induced atherosclerotic lesions in mice. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:2040–7. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Davenport P, Tipping P. The role of interleukin-4 and interleukin-12 in the progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1117–25. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63471-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grohmann U, Van Snick J, Campanile F, Silla S, Giampietri A, Vacca C, et al. IL-9 protects mice from Gram-negative bacterial shock: suppression of TNF-alpha, IL-12, and IFN-gamma, and induction of IL-10. J Immunol. 2000;164:4197–203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.8.4197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Frostegård J, Ulfgren AK, Nyberg P, Hedin U, Swedenborg J, Andersson U, et al. Cytokine expression in advanced human atherosclerotic plaques: dominance of pro-inflammatory (Th1) and macrophage-stimulating cytokines. Atherosclerosis. 1999;145:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vadiveloo P, Stanton H, Cochran F, Hamilton J. Interleukin-4 inhibits human smooth muscle cell proliferation. Artery. 1994;21:161–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vadiveloo P, Filonzi E, Stanton H, Hamilton J. G1 phase arrest of human smooth muscle cells by heparin, IL-4 and cAMP is linked to repression of cyclin D1 and cdk2. Atherosclerosis. 1997;133:61–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Barks J, McQuillan J, Iademarco M. TNF-alpha and IL-4 synergistically increase vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:4532–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Lee YW, Kühn H, Hennig B, Neish AS, Toborek M. IL-4-induced oxidative stress upregulates VCAM-1 gene expression in human endothelial cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:83–94. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2000.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Walch L, Massade L, Dufilho M, Brunet A, Rendu F. Pro-atherogenic effect of interleukin-4 in endothelial cells: modulation of oxidative stress, nitric oxide and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression. Atherosclerosis. 2006;187:285–91. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Lee YW, Eum SY, Chen KC, Hennig B, Toborek M. Gene expression profile in interleukin-4-stimulated human vascular endothelial cells. Mol Med. 2004;10:19–27. doi: 10.2119/2004-00024.lee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fukushi J, Ono M, Morikawa W, Iwamoto Y, Kuwano M. The activity of soluble VCAM-1 in angiogenesis stimulated by IL-4 and IL-13. J Immunol. 2000;165:2818–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.5.2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Grehan JF, Levay-Young BK, Fogelson JL, François-Bongarçon V, Benson BA, Dalmasso AP. IL-4 and IL-13 induce protection of porcine endothelial cells from killing by human complement and from apoptosis through activation of a phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. J Immunol. 2005;175:1903–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jordan NJ, Watson ML, Williams RJ, Roach AG, Yoshimura T, Westwick J. Chemokine production by human vascular smooth muscle cells: modulation by IL-13. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:749–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ruetten H, Thiemermann C. Interleukin-13 is a more potent inhibitor of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in smooth muscle cells than in macrophages: a comparison with interleukin-4 and interleukin-10. Shock. 1997;8:409–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Chen X, Kelemen S, Autieri M. Expression of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor is induced in injured rat carotid arteries and mediates vascular smooth muscle cell migration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C81–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00322.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Autieri M, Carbone C, Mu A. Expression of allograft inflammatory factor-1 is a marker of activated human vascular smooth muscle cells and arterial injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:1737–44. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.7.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Taki H, Sakai T, Sugiyama E, Mino T, Kuroda A, Taki K, et al. Monokine stimulation of interleukin-11 production by human vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Atherosclerosis. 1999;144:375–80. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(99)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kirkiles-Smith N, Mahboubi K, Plescia J, McNiff J, Karras J, Schechner J, et al. IL-11 protects human microvascular endothelium from alloinjury in vivo by induction of survivin expression. J Immunol. 2004;172:1391–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Temann U, Laouar Y, Eynon E, Homer R, Flavell R. IL9 leads to airway inflammation by inducing IL13 expression in airway epithelial cells. Int Immunol. 2007;19:1–10. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Oral H, Kotenko S, Yilmaz M, Mani O, Zumkehr J, Blaser K, et al. Regulation of T cells and cytokines by the interleukin-10 (IL-10)-family cytokines IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24 and IL-26. Eur J Im-munol. 2006;36:380–8. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]