Abstract

Rotator cuff tears are difficult to manage because of the structural and mechanical inhomogeneity of the supraspinatus tendon. Previously, we showed that with the arm at the side, the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons mechanically interact such that conditions that increase supraspinatus tendon strain, such as load or full-thickness tears, also increase infraspinatus tendon strain. This suggests that the infraspinatus tendon may shield the supraspinatus tendon from further injury while becoming at increased risk of injury itself. In this study, the effect of glenohumeral abduction angle on the interaction between the two tendons was evaluated for supraspinatus tendon partial-thickness tears and two repair techniques. Principal strains were quantified in both tendons for 0°, 30° and 60° of glenohumeral abduction. Results showed that interaction between the two tendons is interrupted by an increase in abduction angle for all supraspinatus tendon conditions evaluated. Infraspinatus tendon strain was lower at 30° and 60° than at 0° abduction angle. In conclusion, interaction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons is interrupted with increase in abduction angle. Additionally, 30° abduction should be further evaluated for management of rotator cuff tears and repairs as it is the angle at which both supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon strain is decreased.

Keywords: joint position, rotator cuff tears, mechanical interactions, supraspinatus strain, infraspinatus strain

INTRODUCTION

As a unit, the muscles and tendons of the rotator cuff are critical in allowing the shoulder joint its wide range of motion and stability 1–3. In particular, the versatile motion of the shoulder joint regularly subjects the rotator cuff tendons to complex loads. In turn, these loads result in a high incidence of rotator cuff pathology, including tears. Of the four rotator cuff tendons, the supraspinatus has the highest incidence of tearing 4–6. This is believed to be attributed not only to the location of the supraspinatus directly under the acromion, but also due to the high demands placed on the tendon during routine glenohumeral motion. For example, the supraspinatus is critical in initiating arm abduction and stabilizing the glenohumeral joint throughout all ranges of motion by compressing the humeral head against the glenoid fossa 7.

Due to its high incidence of injury, several studies have investigated the loading environment in the supraspinatus tendon to evaluate causes and pathology of rotator cuff tears 8, 9 and potential repair techniques. Traditionally, tendon tears were repaired using an open surgical approach with several suturing techniques, with grasping sutures (Mason-Allen) being most common 10. Arthroscopic techniques for cuff repair offer a less invasive alternative 11 that has become more commonly used in recent years 12, 13. Regardless of the technique used, the goal of rotator cuff repair is to re-establish normal rotator cuff mechanics 14.

Strain measurements are commonly used to investigate the loading environment in the supraspinatus tendon 15, 16. Bey et al. showed that strain in the supraspinatus tendon increased with an increase in abduction angle 17. In that study, the effect of tear was also evaluated and was found to be non-significant in joint positions that allow the tendon greater contact with the humeral head. It was thought that contact with the humeral head provides a strain shielding mechanism that may mask the effect of a tendon tear. In addition, strain in a repaired supraspinatus tendon has been shown to be impacted by the joint position 18, emphasizing the effect of joint position on the loading environment for the repaired as well as the intact, and torn supraspinatus tendons.

Previously we have shown that with the arm at the side, the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons mechanically interact resulting in increases in infraspinatus tendon strain under conditions that cause increased strains in the supraspinatus tendon 19. Since changes in abduction angle significantly impact the loading environment in the supraspinatus tendon, it is likely that the interaction between the two tendons is affected by the joint abduction angle.

To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the interaction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons with changes in abduction angle in conjunction with changes in joint load and the commonly occurring partial-thickness supraspinatus tears and repairs. Therefore, the objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of alterations in abduction angle on strain in the intact infraspinatus tendon through a series of partial- thickness supraspinatus tears, repairs and loads. We hypothesize that: at all supraspinatus tendon loads, (H1) increasing the abduction angle will cause an increase in maximum and a decrease in minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons for all tears (H2) and repairs evaluated.

METHODS

Ten healthy, fresh-frozen cadaveric shoulders (average age 48.7±15.1 yrs) were carefully dissected free of soft tissue, retaining only the proximal humerus, supraspinatus tendon, and infraspinatus tendon. Specimens with grossly visible rotator cuff tears or fraying of the bursal or articular surface were excluded from the study. The proximal end of the infraspinatus tendon was sutured using a Krakow stitch to allow application of a load. Prior to mechanical testing, the specimens were maintained in a physiologic bath of phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

The bursal side of both the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus tendons was air-brushed with black paint to create a fine speckled texture for subsequent texture correlation strain analysis using Vic2D (Version 4.4.1, Correlated Solutions Inc., Columbia, SC). This commercial software utilizes a texture correlation algorithm 20 to determine displacements of pixels in the undeformed and deformed images as previously described 19.

The diameter of the humeral head was estimated along the axial, coronal and sagittal planes and the centers of each plane were each marked on multiple surfaces of the humeral head (typically at least 4 points were marked), so as to allow appropriate positioning in the fixture. The specimen was carefully mounted in Poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) in custom grips with the center of the humeral head placed in a set position. This allowed changes in abduction without the need to readjust the line of loading for either tendon. The supraspinatus tendon was attached to a testing machine (5543, Instron, Norwood, MA) to allow for controlled loading and the infraspinatus tendon was attached to a pulley system with a nominal, constant load of 9.8 N19 (figure 1).

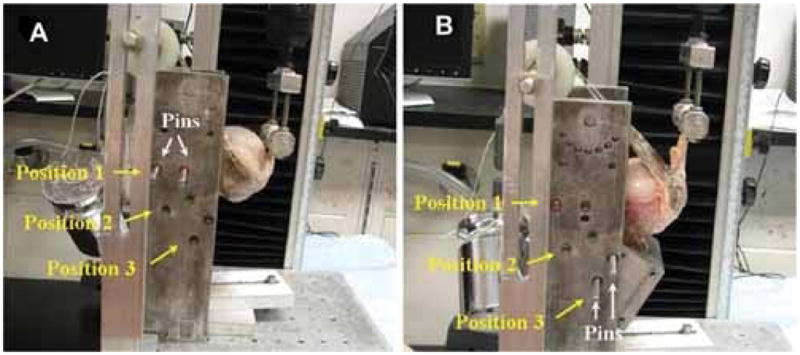

Figure 1.

Experimental setup allows for reproducible and repeatable changes in glenohumeral abduction angle. The humerus is moved and pinned in 1 of three positions that correspond to the three abduction angles evaluated.

The joint was initially positioned such that both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons were loaded along their physiologically neutral position, defined by a 0° humeral abduction, rotation and flexion angle. The effect of joint position was then evaluated at 30° and 60° of glenohumeral abduction.

The supraspinatus tendon loading protocol consisted of preconditioning followed by a constant ramp to 90N at a strain rate of 0.1% per second of the length of the tendon 19. The loading protocol was applied to the intact supraspinatus tendon at neutral position and at 30° and 60° of glenohumeral abduction. An anterior-side partial-thickness (33% thickness) tear through 66% of the width of the tendon was then surgically created in the bursal side of the supraspinatus tendon and the loading protocol was repeated again at all 3 abduction angles. The tear was then extended through 66% of the thickness of the tendon and the loading protocol was repeated once again at all 3 abduction angles. Finally, the tear was extended through 100% of the thickness of the tendon and the loading protocol was repeated once again at all 3 abduction angles. Both tendons were generously moistened with PBS after each completion of the loading protocol

Two supraspinatus tendon repair techniques were then evaluated in random order. The first repair technique utilized the modified Mason-Allen grasping suture in the supraspinatus tendon with transosseous bone fixation (Transosseous). Specifically, the supraspinatus tendon was secured with two #2 FiberWire sutures (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) in a modified Mason-Allen configuration at the tendon edge. Next, two transosseous tunnels were created, each starting at the lateral edge of the articular cartilage and exiting the lateral cortex of the proximal humerus, in line with the overlying sutures. The deep limb of each suture was passed through the underlying tunnel. The superficial limb of each suture was then passed through a second bone tunnel, each starting at the lateral aspect of the supraspinatus footprint and exited the lateral humeral cortex proximal to the deep tunnel. The deep and superficial limbs of each suture were tied over the lateral humeral cortex, advancing the supraspinatus tendon edge to the greater tuberosity. All sutures were hand-tied and tensioned using a calibrated scale, to a predetermined load that remained constant across all repairs.

The second repair technique evaluated was a “transosseous-equivalent” repair utilizing a 4-suture-bridge technique (Arthroscopic) as described by Tibone et al 21. Briefly, a punch was used to create two holes at the lateral edge of the articular cartilage (in the same location as the deep tunnel utilized in for the transosseous repair). Next the hole was tapped and a 5.5 mm × 15 mm Bio-Corkscrew FT suture anchor (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) was placed in each hole. Each suture anchor was preloaded with two #2 FiberWire sutures, one of which was removed prior to insertion. Each limb of suture was sequentially brought through the supraspinatus tendon using a free needle. The two suture limbs from the same anchor were then tied in a horizontal mattress configuration. Similar to the transosseous repair, sutures were tied by hand and similarly tensioned. Next, a different punch was used to create two holes in the lateral humerus cortex, 15 mm distal to the lateral supraspinatus footprint. Into each of these holes, a 4.5 mm × 18.5 mm Bio-PushLock anchor (Arthrex Inc., Naples, FL) was inserted, securing one limb of suture from each of the knots previously tied.

After supraspinatus tendon repair, the previously described loading protocol was applied at each abduction angle. The repair was then undone and the tendon was hydrated and allowed to recover. The supraspinatus tendon was then repaired using the second repair technique and loaded at each abduction angle.

Digital images were taken of the insertion site of both the supraspinatus and the infraspinatus tendons at 1 second intervals during the loading ramp phase of the mechanical testing protocol. For each supraspinatus tendon tear level (intact, 33% and 66% partial-thickness, and 66% full thickness through 66% of the width of the tendon), images at 5N, 30N, 60N and 90N of supraspinatus tendon loads were chosen for evaluation for the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons. Similarly, for transosseous and arthroscopic supraspinatus tendon repairs, images at 5N, 30N, 60N and 90N of supraspinatus tendon loads were chosen for evaluation for the infraspinatus tendon only. Local strains in the repaired supraspinatus tendon could not be evaluated due to tendon buckling at the repair site.

As previously described, a region of interest in the insertion site of the infraspinatus and the consistently intact posterior 1/3 of the supraspinatus tendons was outlined and a digital grid of nodes was then fitted in the region of interest 19. Displacements of the nodes between the 5N load and each of the 30, 60N and 90N loads were calculated and the two-dimensional Lagrangian finite strain tensor (εxx, εyy, and εxy) from which the principal strain components were calculated19. Average maximum and minimum principal strains were determined for the insertion site of the infraspinatus tendon. Principal strain components were calculated and reported because they completely and simply depict the loading environment by absorbing the shear strain component into the orthogonal tensile (maximum principal strain) and compressive (minimum principal strain) components through a coordinate rotation. The complex strain environment can then be fully characterized by the tensile and compressive deformation indicated by average maximum and minimum principal strain, respectively.

The tendon insertion sites are not planar but rather slightly curved due to the curvature of the humeral head. However, the region of interest is small and highly magnified minimizing the effect of the curvature and allowing the use of a planar estimate. Despite that, for mechanical rigor, from this point forward, we will term our “strain” measurements as “apparent strain”.

The effect of abduction angle on apparent average maximum and minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was evaluated with a one-way ANOVA with repeated measures (with post-hoc Bonferroni) for each supraspinatus tendon load, tear level and repair technique. To further explain the results, the supraspinatus tendon was similarly evaluated for all intact and torn conditions. As previously mentioned, the same analysis of the supraspinatus tendon could not be done for the repaired cases due tendon buckling at the repair site. Significance was set at p ≤ 0.05 and a trend at p ≤ 0.1 (denoted by * and # respectively).

RESULTS

Results did not support our hypotheses regarding the effect of glenohumeral abduction angle on apparent average maximum or minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon. In the supraspinatus tendon, apparent average maximum principal strain was highest at 60° abduction and lowest at 30° abduction. In contrast to our hypothesis, apparent average minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was generally most compressive at 0° abduction.

Effect of Abduction angle for partial-thickness tears

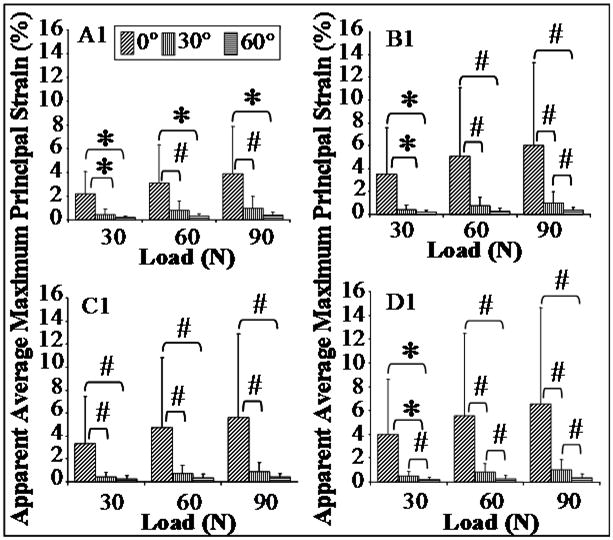

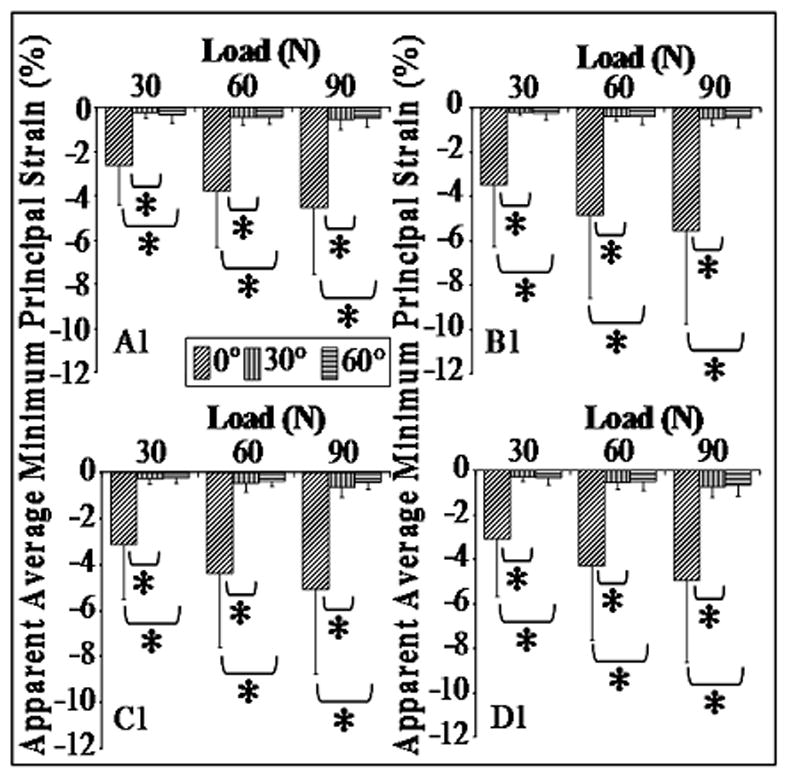

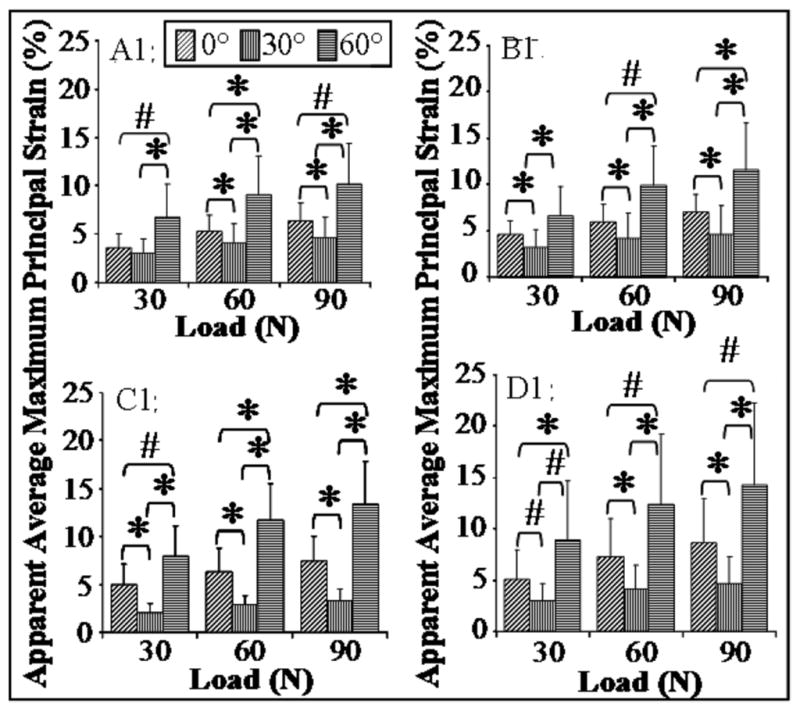

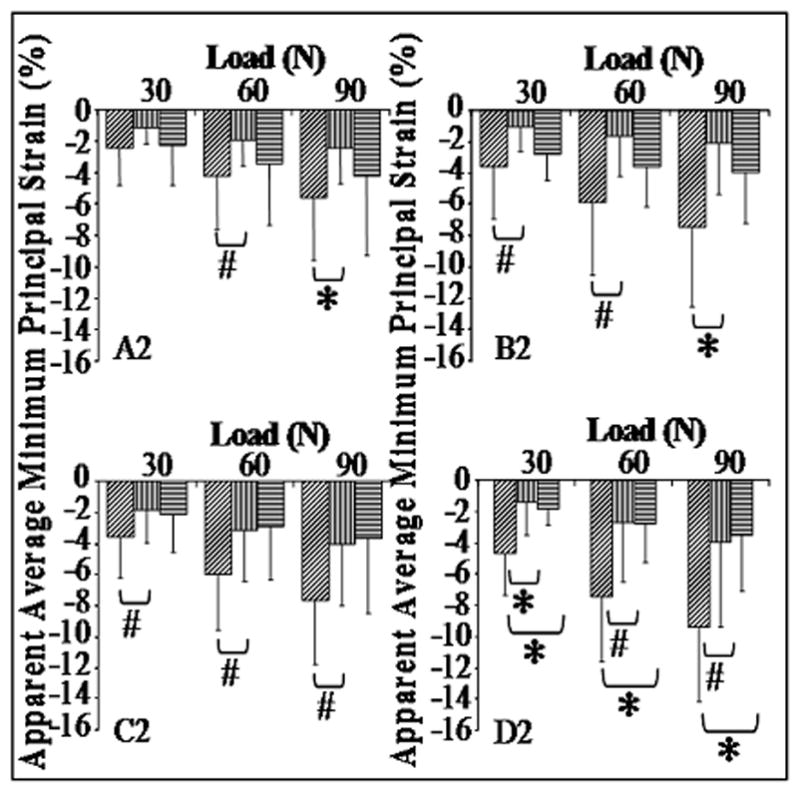

In contrast to our hypothesis (H1), for all tears evaluated, maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was higher at 0° abduction than at 30° and 60° abduction. Strain maps showing the apparent maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon at 0° and 30° are shown in figure 2 and results are shown in figure 3. Similarly, in contrast to our hypothesis, apparent average minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was significantly more compressive at 0° abduction than at 30° or 60° abduction (figure 5). However, supporting our hypothesis (H1), this unexpected effect of abduction angle on infraspinatus tendon maximum and minimum principal strain was consistent for all loads and tears evaluated. Since the strain values at 30° and 60° abduction were extremely small, corresponding to minimal displacements (less than 5 pixels) which were therefore not reliable, no comparisons regarding the effect of tear or load at 30° and 60° abduction were made.

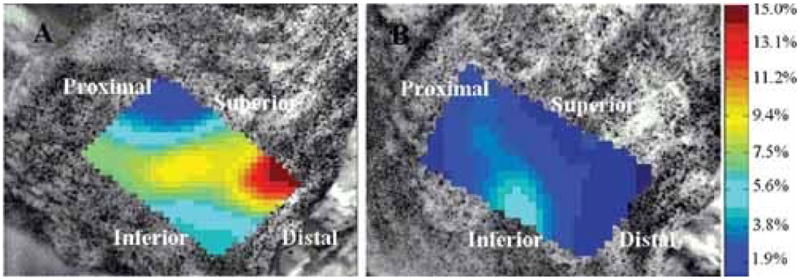

Figure 2.

Strain maps showing apparent maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon for the intact supraspinatus tendon at 60N at (A) 0° abduction and (B) 30° abduction. Contrary to hypothesis, apparent maximum principal strain was higher at 0° than at 30° abduction.

Figure 3.

For all supraspinatus tendon tears, effect of abduction angle on apparent average maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon. For all supraspinatus tendon tears (A1:intact, B1:33% partial-thickness, C1:66% partial-thickness and D1:full-thickness), maximum principal strain was higher at 0° abduction than at 30° and 60° abduction.

Figure 5.

For all supraspinatus tendon tears, effect of abduction angle on apparent average minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon. For all supraspinatus tendon tears (A1:intact, B1:33% partial-thickness, C1:66% partial-thickness and D1:full-thickness), minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was more compressive at 0° than at 30° and 60° abduction.

In the supraspinatus tendon, as expected, apparent average maximum principal strain was greater at 60° abduction than at 0° and 30° abduction. Interestingly, apparent average maximum principal strain in the supraspinatus tendon was lowest at 30° abduction and not at 0° abduction, highlighting potential clinical relevance of this joint position (30° abduction) for management of rotator cuff tears, since both tendons experience lowest strains (figure 4). Apparent average minimum principal strain was more compressive at 0° abduction than at 30° (figure 6). For the 100% full-thickness tear case, apparent average minimum principal strain was significantly more compressive at 0° than that at 30° and 60° abduction.

Figure 4.

For all supraspinatus tendon tears, effect of abduction angle on apparent average maximum principal strain in the supraspinatus tendon. For all supraspinatus tendon tears (A1:intact, B1:33% partial-thickness, C1:66% partial-thickness and D1:full-thickness), maximum principal strain was higher at 0° than at 30°, and at 60° abduction than at 0° and 30° abduction.

Figure 6.

For all supraspinatus tendon tears, effect of abduction angle on apparent average minimum principal strain in the supraspinatus tendon. Minimum principal strain in the supraspinatus tendon was lower at 0° than at 30° abduction (for A1: intact, B1: 33% partial-thickness tear, and C1: 66% partial-thickness tear) and lower than 30° and 60° abduction for the 100% full-thickness tear (D1).

Effect of Abduction angle for supraspinatus tendon repairs

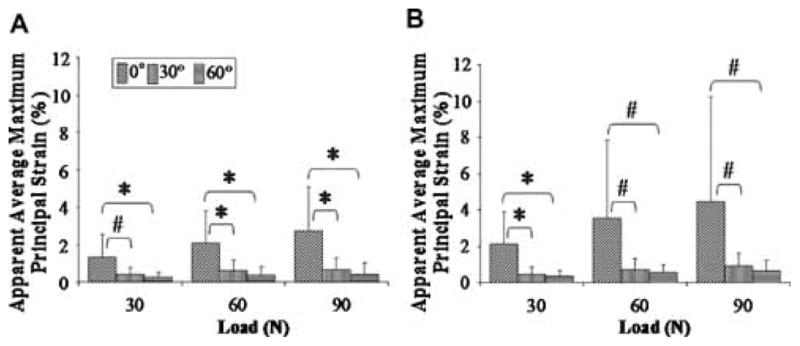

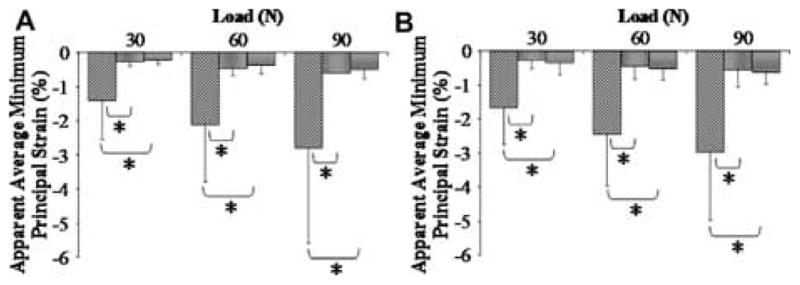

The effect of abduction angle on maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon for the double-row suture anchor repair and the transosseous Mason-Allen repair techniques was the same as that observed for the intact supraspinatus tendon case. Specifically, at all loads, average apparent maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was higher at 0° abduction than at 30° and 60° abduction (figure 7). Similarly, in contrast to H2, at all loads, average apparent minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon was more compressive at 0° abduction than at 30° and 60° abduction (figure 8).

Figure 7.

Effect of abduction on apparent average maximum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon following (A) arthroscopic and (B) transosseous repairs. For both techniques, apparent average maximum principal strain was significantly higher at 0° than at 30° and 60° abduction.

Figure 8.

Effect of abduction on apparent average minimum principal strain in the infraspinatus tendon following (A) arthroscopic and (B) transosseous repairs. For both techniques apparent average minimum principal strain was significantly more compressive at 0° than at 30° and 60° abduction.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that mechanical interactions between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons cause the infraspinatus tendon to experience increase in strain under conditions that cause increase in supraspinatus tendon strain 19. Results indicate that the interaction between the two tendons is interrupted with the increase in abduction angle from 0° to 30° and 60°. Since altering the glenohumeral abduction from 0° to 60° caused an increase in maximum principal strain in the supraspinatus tendon in conjunction with a drop in infraspinatus tendon strain to near 0%, these results support that the interaction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons may have a strain shielding effect. In this case, the interruption of the interaction (supported by a very significant drop in strain in the infraspinatus tendon) between the two tendons was associated with an increase in strain in the supraspinatus tendon.

Interestingly, the observed effect of abduction angle was consistent for all partial-thickness tears, repairs and loads evaluated. Since the mechanical interaction between the two tendons occurs at 0° abduction, it is likely that the interaction of the humeral head with the supraspinatus tendon is integral to the interaction between the two tendons. In this case, the greater contact area between the humeral head and the supraspinatus tendon may anatomically position the two tendons so as to optimize their interaction. These results may have significant clinical implications in the management of supraspinatus tendon tears or repairs post-surgery. For instance, it is possible that the increase in strain in the infraspinatus tendon that results from the mechanical interaction between the two tendons may relieve the supraspinatus tendon from greater strains thereby minimizing its risk of further injury. Alternatively, the strains experienced by the infraspinatus tendon result secondarily from supraspinatus tendon loading, and is therefore not along the long axis of the infraspinatus tendon. Therefore, it is possible that the chronic effects of the interactions between the two tendons may result in detrimental effect on the infraspinatus in cases where infraspinatus tendon experience high strains. It may be beneficial to position the joint at an angle that causes lowest supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon strains. From our results, a glenohumeral abduction angle of 30° is optimal as it results in the lowest strain in both tendons. Although at this angle, the interaction between the two tendons is likely interrupted, the interaction of each tendon with the humeral head has a greater effect on strain in each tendon than the interaction between the two tendons.

In the supraspinatus tendon, maximum principal strain was lowest at 30° of glenohumeral abduction. Bey et. al. evaluated the effect of abduction angle and generally found a significant increase in maximum principal strain with an increase in abduction angle. Our results are in agreement with those found by Bey for the abduction angles evaluated in both studies. We expect that there is some contact of the humeral head with the supraspinatus tendon at 0° and 30° abduction. At 0° abduction, wrapping of the supraspinatus tendon around the humeral head may cause some strain in the supraspinatus tendon that is relieved at 30° abduction, causing a decrease in strain, while some contact with the humeral head still exists. At 60° abduction, there is no effect of humeral head strain shielding, which coupled with the decrease in infraspinatus tendon strain, causes the supraspinatus tendon to experience highest strains.

This study was conducted in cadaveric human shoulders, and the amount of degeneration present in each shoulder varied. However, the repeated measures design of these experiments minimizes the effect of human variability as all data from one specimen is evaluated in one context. A human cadaveric model allowed adequate evaluation of the effect of mechanical interactions between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons with abduction and supraspinatus tendon tear and repair, however, important in-vivo factors such as tissue degeneration and remodeling due to injury and repair are not accounted for in this model. Additionally, since most rotator cuff tears involve the posterior superior rotator cuff, this study focused on the supraspinatus and infraspinatus (rather than subscapularis). The anatomical confluence at the insertion sites of the infraspinatus and supraspinatus tendons, and the contact of the tendons with the humeral head were expected to directly affect strain at the insertion site of both tendons and thus were included in the model. The anatomical relationship between the tendons was preserved throughout the experiment, mimicking the effect of loading the rotator cuff tendons (including the subscapularis) as a centering force, without the complexity of including additional components.

This study evaluated the interactions of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons at three abduction angles. The data from this study indicates that interactions between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons occur at 0° but not 30° or 60° abduction. Clinical care for patients suffering from a rotator cuff tear or post-operative treatment for patients with a repaired rotator cuff may benefit from consideration of joint position. Based on data from this study, at 30° of glenohumeral abduction, strain is lowest in both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. While this may be an optimal joint position to minimize the risk of tear propagation, the possible prolonged absence of mechanical interactions between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendon may also cause detrimental long term changes in the infraspinatus tendon. This data emphasizes the importance of joint position in the loading environment of individual tendons and the overall joint mechanics.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the NIH/NIAMS (AR050176) and the NIH/NIAMS supported Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders (AR050950). We thank Arthrex for providing the suture anchors.

Contributor Information

Nelly Andarawis-Puri, McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania

Andrew F. Kuntz, McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania.

Matthew L. Ramsey, Rothman Institute at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA

Louis J. Soslowsky, McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory, University of Pennsylvania, 424 Stemmler Hall, Philadelphia, PA, Phone: 215-898-8653; Facsimile: 215-573-2133

References

- 1.Friedman RJ, Knetsche RP. Biomechanics of the Rotator Cuff. In: Burkhead, editor. Rotator Cuff Disorders. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Soslowsky LJ, Carpenter JE, Bucchieri JS, Flatow EL. Biomechanics of the rotator cuff. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:17–30. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70261-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itoi E, Hsu HC, An KN. Biomechanical investigation of the glenohumeral joint. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:407–424. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(96)80074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fukuda H. Partial-thickness rotator cuff tears: a modern view on Codman’s classic. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2000;9:163–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SB, Nakajima T, Luo ZP, et al. The bursal and articular sides of the supraspinatus tendon have a different compressive stiffness. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2000;15:241–247. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nobuhara K. The shoulder, its function and clinical aspects. Singapore: World Scientific; 2003. Diseases of the shoulder; pp. 208–237. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muraki T, Aoki M, Uchiyama E, et al. The effect of arm position on stretching of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and posterior portion of deltoid muscles: a cadaveric study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2006;21:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuda H. The Management of Partial-Thickness Tears of the Rotator Cuff. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (Br) 2003;85-B:3–11. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b1.13846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uhthoff HK, Sano H. Pathology of failure of the rotator cuff tendon. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:31–41. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber C, Schneeberger AG, Beck M, Schlegel U. Mechanical strength of repairs of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76:371–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buess E, Steuber KU, Waibl B. Open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a comparative view of 96 cases. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gartsman GM. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:95–106. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gartsman GM. All arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs. Orthop Clin North Am. 2001;32:501–510. x. doi: 10.1016/s0030-5898(05)70219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burkhead WZ., Jr . Rotator Cuff Disorders. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1996. pp. 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bey MJ, Ramsey ML, Soslowsky LJ. Intratendinous strain fields of the supraspinatus tendon: effect of a surgically created articular-surface rotator cuff tear. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:562–569. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.126767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly P, Amis AA, Wallace AL, Emery RJ. Supraspinatus tears: propagation and strain alteration. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:134–138. doi: 10.1067/mse.2003.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bey MJ, Song HK, Wehrli FW, Soslowsky LJ. Intratendinous strain fields of the intact supraspinatus tendon: the effect of glenohumeral joint position and tendon region. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:869–874. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00177-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuckerman JD, Leblanc JM, Choueka J, Kummer F. The effect of arm position and capsular release on rotator cuff repair. A biomechanical study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:402–405. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andarawis-Puri NA, Ricchetti ET, Soslowsky LJ. Interaction between the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons: Effect of anterior supraspinatus tendon full-thickness tear on infraspinatus tendon strain. Am J Sports Med. 2009 doi: 10.1177/0363546509334222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bey MJ, Song HK, Wehrli FW, Soslowsky LJ. A noncontact, nondestructive method for quantifying intratissue deformations and strains. J Biomech Eng. 2002;124:253–258. doi: 10.1115/1.1449917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park MC, Elattrache NS, Ahmad CS, Tibone JE. “Transosseous-equivalent” rotator cuff repair technique. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:1360, e1361–1365. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]