Abstract

Hesperetin, a selective phosphodiesterase (PDE)4 inhibitor, is present in the traditional Chinese medicine, “Chen Pi.” Therefore, we were interested in investigating its effects on ovalbumin- (OVA-) induced airway hyperresponsiveness, and clarifying its rationale for ameliorating asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Hesperetin was revealed to have a therapeutic (PDE4H/PDE4L) ratio of >11. Hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.)) dose-dependently and significantly attenuated the airway hyperresponsiveness induced by methacholine. It also significantly suppressed the increases in total inflammatory cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils, and levels of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-5, interferon-γ, and tumor necrosis factor-α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF). It dose-dependently and significantly suppressed total and OVA-specific immunoglobulin E levels in the BALF and serum. However, hesperetin did not influence xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia, suggesting that hesperetin has few or no emetic effects. In conclusion, the rationales for ameliorating allergic asthma and COPD by hesperetin are anti-inflammation, immunoregulation, and bronchodilation.

1. Introduction

Phosphodiesterases (PDEs) are classified according to their primary protein and complementary (c)DNA sequences, cofactors, substrate specificities, and pharmacological roles. It is now known that PDEs comprise at least 11 distinct enzyme families that hydrolyze adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate (cAMP) and/or guanosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate (cGMP) [1]. PDE1 ~ 5 isozymes, which are calcium/calmodulin dependent (PDE1), cGMP stimulated (PDE2), cGMP inhibited (PDE3), cAMP specific (PDE4), and cGMP specific (PDE5), were found to be present in the canine trachea [2], guinea pig lungs [3], and human bronchi [4]. PDE3 and PDE4 were identified in the guinea pig airway [5], but other isozymes might also be present. PDE4 may adopt two different conformations which have high (PDE4H) and low (PDE4L) affinities for rolipram, respectively. In general, it is believed that inhibition of PDE4H is associated with adverse responses, such as nausea, vomiting, and gastric hypersecretion, while inhibition of PDE4L is associated with anti-inflammatory and bronchodilating effects. Therefore the therapeutic ratio of selective PDE4 inhibitors for use in treating asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined as the PDE4H/PDE4L ratio [6, 7].

Hesperetin (5,7,3′-trihydroxy-4′-methoxyflavanone, mol wt., 302.28), one of the most common flavonoids in Citrus, is also present in herbal medicine as glycosides. For example, hesperidin and neohesperidin are abundantly present in the fruit peel of Citrus aurantium L. (Rutaceae), a well-known traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) called “Chen-Pi”; they are used as an expectorant and stomach tonic, and contain vitamin P, a remedy for preventing capillary fragility and hypertension [8]. These glycosides are easily hydrolyzed by glycosidase to form hesperetin after ingestion. Men with higher hesperetin intake have lower mortality from cerebrovascular disease and lung cancer, and lower incidences of asthma [9]. Because hesperetin was reported to selectively inhibit PDE4 activity [10], and to inhibit the maturation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from patients with asthma [11]. Therefore, we were interested in investigating the PDE4H/PDE4L ratio and suppressive effects of hesperetin on ovalbumin- (OVA-) induced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR), and clarifying its rationale for ameliorating asthma and COPD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Animals

Hesperetin, OVA, methacholine (MCh), aluminum sulfate hexadecahydrate, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), chloralose, urethane, Tris-HCl, Bis-Tris, benzamidine, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), d,l-dithiothreitol, polyethyleneimine, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), bovine serum albumin (BSA), cAMP, cGMP, calmodulin, Dowex resin, Crotalus atrox snake venom, xylazine, and ketamine were purchased from Sigma Chemical (St. Louis, MO, USA). Vinpocetine, erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl)-adenine HCl (EHNA), milrinone, 4-(3-butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidazolidinone (Ro 20-1724), and zaprinast were purchased from Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA). Freund's adjuvant (Mycobacterium butyricum) was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL, USA). Mouse T helper (Th)1/Th2 cytokine CBA kits, and mouse IgE enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) sets were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). Ethyl alcohol and polyethylene glycol (PEG) 400 were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). [3 H]-cAMP, [3 H]-cGMP, and [methyl- 3 H]-rolipram were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Buckinghamshire, UK). Other reagents, such as CaCl2, MgCl2, and NaCl, were of analytical grade. Hesperetin, rolipram, and Ro 20-1724 were dissolved in a mixture of ethyl alcohol and DMSO (1 : 1). Other reagents were dissolved in distilled water.

Male Hartley guinea pigs (500 ~ 600 g) and female BABL/c mice at 8 ~ 12 weeks old were purchased from the Animal Center of the National Science Council (Taipei, Taiwan), and housed in ordinary cages at 22 ± 1°C with a humidity of 50% ~ 60% under a constant 12/12-h light/dark cycle and provided with food and water ad libitum. Under a protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Taipei Medical University, the following in vivo experiments were performed.

2.2. Competitive Inhibition of PDE4 Activity by Hesperetin

Activity of PDE4 in the homogenate of guinea pig lungs or hearts was measured by a two-step procedure according to the previous method [12], using cAMP with [3 H]-cAMP as substrate. The enzyme preparation (25 μL) was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in a total assay volume of 100 μL containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.05% BSA, and 1 μM cAMP with 0.2 μCi [3 H]-cAMP as a substrate alone. In the Lineweaver-Burk analysis, the reaction mixture contained 10 μL of vehicle or inhibitors, at various concentrations of hesperetin or rolipram, a selective PDE4 inhibitor [13] as a reference drug, respectively. The reagents and homogenate were mixed on ice, and the reaction was initiated by transferring the mixture to a water bath at 37°C. Following a 30 min incubation, the reaction was stopped by transferring the reaction vessel to a bath of boiling water for 3 min. After cooling on ice, 20 μL of a 1 mg/mL solution of Crotalus atrox snake venom was added to the reaction mixture, and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. Unreacted [3 H]-cAMP was removed by the addition of 500 μL of a 1-in-1 Tris-HCl (40 mM) buffer suspension of Dowex resin (1 × 8-200) with incubation on ice for 30 min. Each tube was then centrifuged at 3700 g for 2 min, and 150 μL of the supernatant was removed for liquid scintillation counting. Less than 10% of the tritiated cyclic nucleotide was hydrolyzed in this assay. The total protein in each fraction used was assayed according to the previous method [14]. PDE activity is reported as nmol/mg/min.

2.3. Determination of PDE4H Values

When the above-mentioned guinea pigs were sacrificed, the whole brains were removed and homogenized with a glass/Teflon homogenizer (Glas-Col, Terre Haute, IN, USA) in 10 volumes of cold medium (pH 6.5) containing 20 mM Bis-Tris, 2 mM benzamidine, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM sodium chloride, 0.1 mM PMSF, and 1 mM dithiothreitol. At 4°C, the homogenate was centrifuged at 170 g for 5 min to remove connective tissues and blood vessels. The suspended homogenate was then recentrifuged at 40,000 g for 30 min to separate the cytosolic and particulate portions. The particulate portion was resuspended in a suspension at a concentration of 400 mg/mL (wet weight/volume), after washing 3 times with homogenizing buffer. The particulate portion mainly consisted of cell membranes. The binding ability of hesperetin (3 ~ 300 μM) on high-affinity rolipram-binding sites (HARBSs) of membranes was determined by replacing 2 nM [3 H]-rolipram in a reaction buffer at 30°C for 1 h, according to the method described by previous investigators [13, 15] and modified by us. Briefly, the reaction buffer consisted of 50 mM Tris-HCl and 5 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.5). The total volume of the reaction mixture was 25 μL, consisting of 10 μL of the particulate suspension, 10 μL of [3 H]-rolipram, and 5 μL of hesperetin or reference drugs, such as rolipram (0.1 ~ 1,000 nM) and Ro 20-1724 (1 ~ 10,000 nM) [16]. After 1 h, the reaction was terminated by moving the reaction vessel into crushed ice. Then the reaction mixture was transferred onto Whatman GF/B glass-fiber filters, which were soaked in a 0.3% polyethyleneimine solution in a minifunnel. The reaction mixture was filtered by centrifugation at 90 g for 10 s, and the filtrate was collected into a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube with the top adapted to the outlet of the minifunnel. The filters were washed with 300 μL of reaction buffer three times each in the same way, and transferred into 2 mL of cocktail for radiation counting (total binding) using a β-scintillation counter (Beckman, Fullerton, CA, USA). Nonspecific binding, which was defined in the presence of 10 μM Ro 20-1724, was subtracted from total binding to yield specific binding. Effective concentration (EC50) values of hesperetin, rolipram, and Ro 20-1724, at which a half of the [3 H]-rolipram that was bound onto HARBSs of cell membranes was displaced, were defined as PDE4H values, and these were related to any adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and hypergastric secretion [7].

2.4. Airway Hyperresponsiveness (AHR)

In vivo, ten female BABL/c mice in each group were sensitized by an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of 20 μg of OVA emulsified in 2.25 mg of an aluminum hydroxide gel, prepared from aluminum sulfate hexadecahydrate, in a total volume of 100 μL on days 0 and 14. On day 21, these mice were injected with (i.p.) 100 μL of a mixture of 1% OVA and Freund's complete adjuvant (1 : 1). Mice were challenged via the airway using 1% OVA in saline for 30 min on days 28, 29, and 30 by ultrasonic nebulization. After the last of the primary OVA challenges [17], AHR was assessed on day 32 (48 h after 1% OVA provocation) in each group. Each group of mice was administered (i.p.) the vehicle (control) or 3 ~ 30 μmol/kg of hesperetin 2 h before and 6 and 24 h after OVA provocation. For comparison, sham-treated mice were sensitized but challenged with saline instead of 1% OVA (nonchallenged). The vehicle, a mixture of DMSO : ethyl alcohol : PEG 400 : saline (0.5 : 0.5 : 14.5 : 14.5, v/v), or hesperetin was administered (i.p.) at a volume of 0.01 mL/g of body weight. AHR was assessed in unrestrained animals by barometric plethysmography [18] using a whole-body plethysmograph (WBP) and analyzed using software of Life Science Suite P3 Analysis Modules (Gould, LDS Test and Measurement LLC, Valley View, OH, USA). Mice were placed into the main chamber of the WBP, and the baseline enhanced pause (P enh) value was determined. Then mice were first nebulized with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and subsequently with increasing doses (6.25 ~ 50 mg/mL) of MCh for 3 min for each nebulization, followed by readings of breathing parameters for 3 min after each nebulization to determine P enh values. Twenty-four hours after P enh determination, these mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and the lungs were lavaged via a tracheal tube with PBS (1 × 1.0 mL, 37°C). After lavage, blood was collected from the jugular vein and allowed to sit so that it would coagulate. The collected bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) and coagulated blood were, respectively, centrifuged at 630 g for 7 min and at 3700 g for 10 min at 4°C. After centrifugation, the BALF and serum supernatants were stored at −20°C until determination of cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-2, IL-4, IL-5, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and interferon (IFN)-γ by flow cytometric methods [19] using mouse T helper (Th)1/Th2 cytokine CBA kits, and of total immunoglobulin (Ig)E using ELISA kits (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the respective recommendations of the manufacturers. OVA-specific IgE was measured as described previously [20]. Wells were coated with 100 μL of OVA (20 μg/mL) instead of the capture antibody. Levels are expressed in arbitrary units, where 1 arbitrary unit equals the optical density of the sample divided by the optical density of unchallenged mouse serum or BALF (standard). The BALF pellet was resuspended in ACK lysing buffer (1.658 g NH4Cl, 0.2 g KHCO3, and 1.44 mg EDTA in 200 mL of water) to lyse the residual erythrocytes in each sample. The number of inflammatory cells was counted using a hemocytometer (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA, USA). Cytospun slides were stained and differentiated in a blinded fashion by counting at least 100 cells under light microscopy.

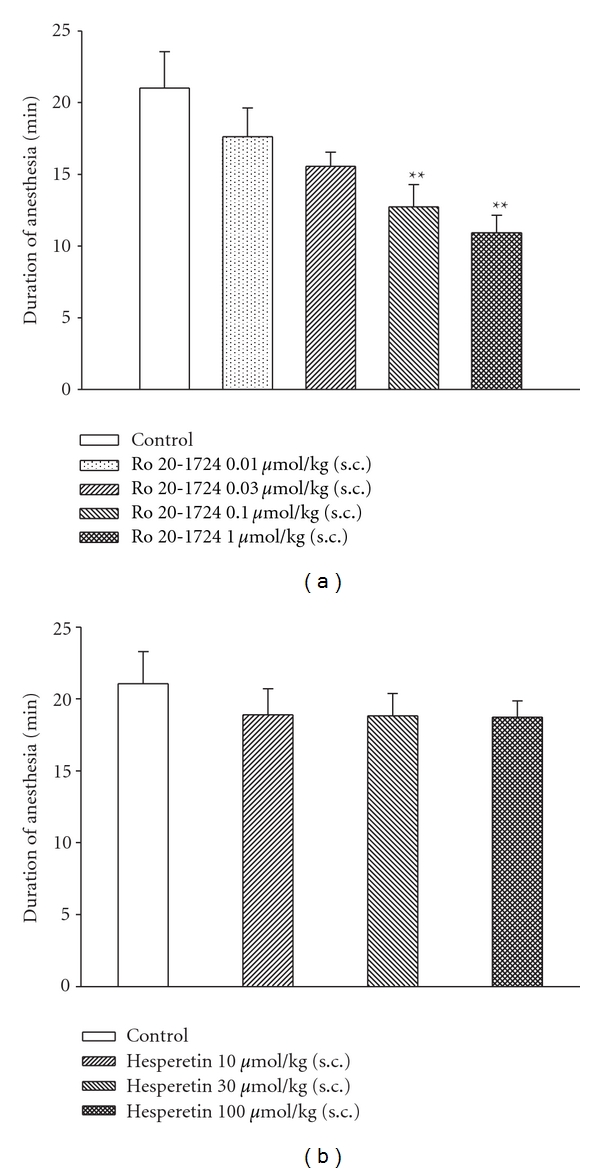

2.5. Xylazine/Ketamine-Induced Anesthesia

According to a previously described method [21] and modified by us, hesperetin (10 ~ 100 μmol/kg, subcutaneously (s.c.)) or Ro 20-1724 (0.01 ~ 1 μmol/kg, s.c.), a reference drug, was, respectively, injected into 8 ~ 12-week-old female BALB/c mice 1 or 0.25 h prior to an i.p. injection of xylazine (10 mg/kg)/ketamine (70 mg/kg). The vehicle (control) for hesperetin or Ro 20-1724 was a mixture of DMSO : ethyl alcohol : PEG 400 : saline (0.5 : 0.5 : 14.5 : 14.5, v/v). After loss of the righting reflex (i.e., when a mouse remained on its back and no longer spontaneously righted itself to a prone position), the duration of anesthesia was measured until its return as the endpoint [21].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All values are given as the mean ± SEM. Differences among values were statistically calculated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and then determined by Dunnett's test. The difference between two values, however, was determined by Student's t-test. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Competitive Inhibition of PDE4 Activity by Hesperetin

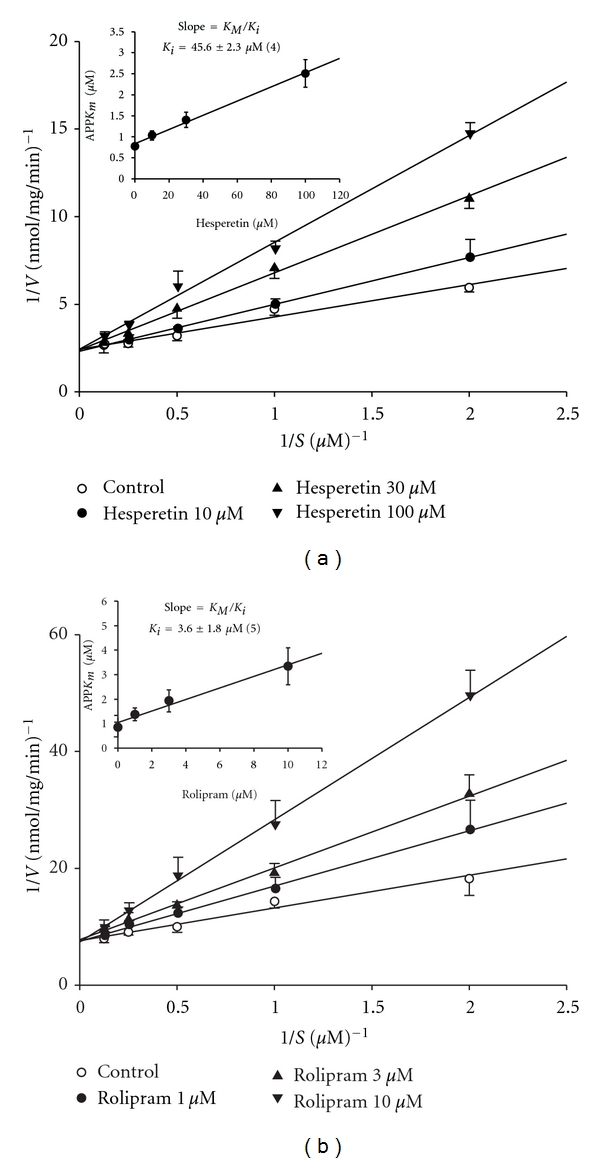

According to the Lineweaver-Burk analysis, hesperetin (10 ~ 100 μM) and rolipram (1 ~ 10 μM) competitively inhibited PDE4 activity (Figure 1), because 1/Vmax values were not significantly affected by various concentrations of hesperetin (a) or rolipram (b). Their K i values were, respectively, calculated to be 45.6 ± 2.3 (n = 4) and 3.6 ± 1.8 (n = 5) μM (Figure 1 inset).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of PDE4 induced cAMP hydrolysis by hesperetin (a) and rolipram (b). Activities of PDE4 in the presence of various concentrations of hesperetin or rolipram, and the substrate (cAMP) were plotted according to a Lineweaver-Burk analysis. K i was determined from the equation of the apparent K m as a function of the inhibitor concentration (inset). Each value represents the mean ± SEM. The experimental number for hesperetin, and rolipram was 4 and 5, respectively.

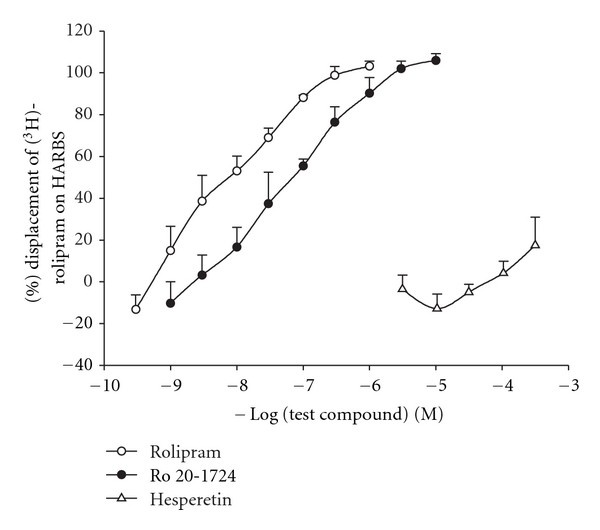

3.2. PDE4H Values

Rolipram (0.1 ~ 1,000 nM) and Ro 20-1724 (1 ~ 10,000 nM), concentration-dependently and effectively displaced 2 nM [3H]-rolipram binding on HARBSs of guinea pig brain cell membranes (Figure 2). However, hesperetin even at 300 μM displaced those only by 17.5 ± 9.5% (n = 4) (Figure 2). The respective EC50 (PDE4H) values of rolipram, Ro 20-1724, and hesperetin for displacing [3H]-rolipram binding were 7.5 ± 3.4 (n = 4) nM, 45.6 ± 9.7 (n = 4) nM, and >300 μM.

Figure 2.

Displacement of [3H]-rolipram by rolipram, Ro 20-1724, and hesperetin in high-affinity rolipram binding sites of guinea pig brain particulate. Each value represents the mean ± SEM. The experimental number for each was 4.

3.3. Supsression of Airway Hyperresponsiveness In Vivo

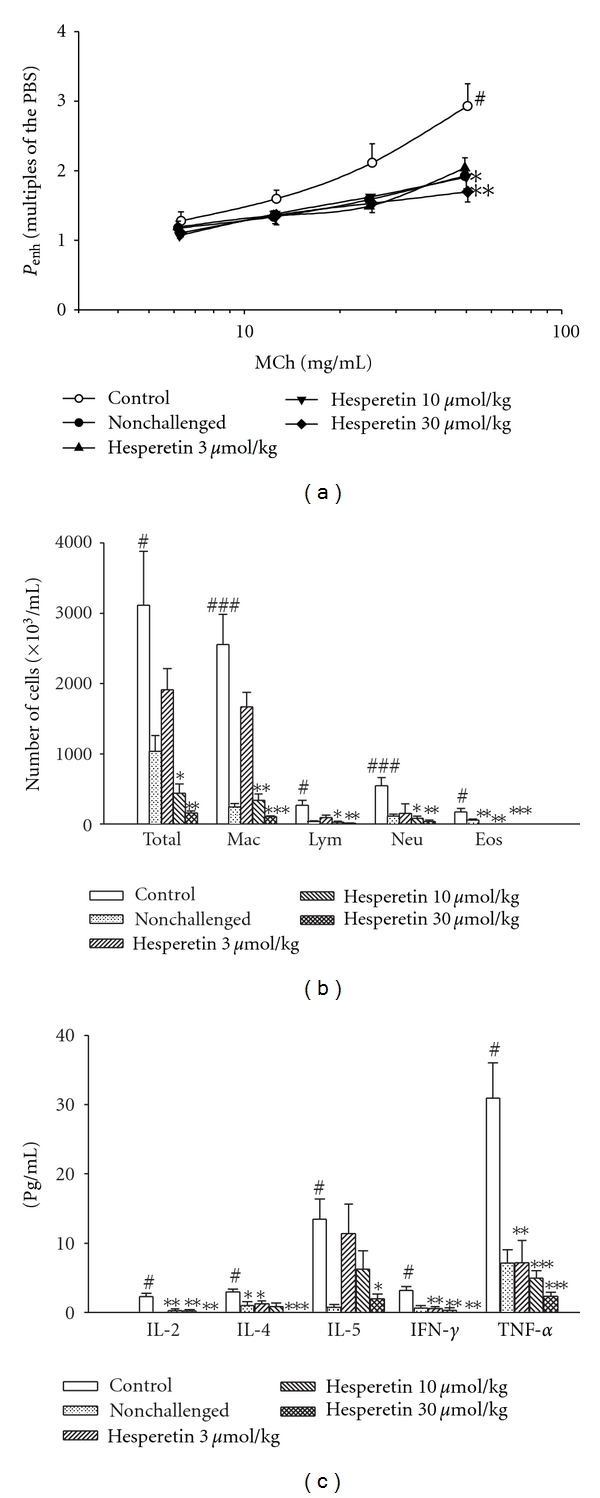

P enh values at the baseline for the control (vehicle), nonchallenged, and 3, 10, and 30 μmol/kg hesperetin groups were 2.37 ± 0.04, 2.40 ± 0.05, 2.42 ± 0.03, 2.35 ± 0.05, and 2.42 ± 0.04, respectively, and these values did not significantly differ from each other. P enh values with PBS nebulization for each group were 2.42 ± 0.05, 2.43 ± 0.03, 2.38 ± 0.05, 2.36 ± 0.04, and 2.44 ± 0.05, respectively, which also did not significantly differ from each other. Administration of nebulized PBS did not affect the P enh value of the baseline in each group. However, MCh (6.25 ~ 50 mg/mL) concentration-dependently increased P enh values from 1-fold with PBS exposure to 2.93 ± 0.32-fold in control sensitized and challenged mice (Figure 3(a)). P enh values of MCh at 50 mg/mL in control sensitized and challenged mice were significantly enhanced compared to those in non-challenged mice. Hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently and significantly attenuated the enhancement of P enh values induced by 50 mg/mL MCh (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

Effects of hesperetin (10 ~ 100 μmol/kg, i.p.) on the enhanced pause (P enh) (a), inflammatory cells (b), and cytokines (c) in sensitized mice which received aerosolized methacholine (6.25 ~ 50 mg/mL) 2 days after primary allergen challenge. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01, and ### P < 0.001, compared to the nonchallenged group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, compared to the control (vehicle) group. The number of mice in each group was 10. Total: total cells; Mac: macrophages; Lym: lymphocytes; Neu: neutrophils; Eos: eosinophils; IL: interleukin; IFN: interferon; TNF: tumor necrosis factor.

3.4. Suppression of Inflammatory Cells in BALF

Total inflammatory cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils from the BALF of control sensitized and challenged mice significantly increased compared to those of nonchallenged mice (Figure 3(b)). Hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) significantly suppressed the increases in total inflammatory cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils. Hesperetin even at 3 μmol/kg (i.p.) also suppressed the increase of eosinophils (Figure 3(b)).

3.5. Suppression of Cytokines in BALF

Compared to those in nonchallenged mice, levels of cytokines, such as IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, in the BALF of control sensitized and challenged mice significantly increased (Figure 3(c)). Hesperetin (3 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) significantly suppressed increases in levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, and TNF-α with the exception of IL-5 at doses of 3 and 10 μmol/kg (Figure 3(c)).

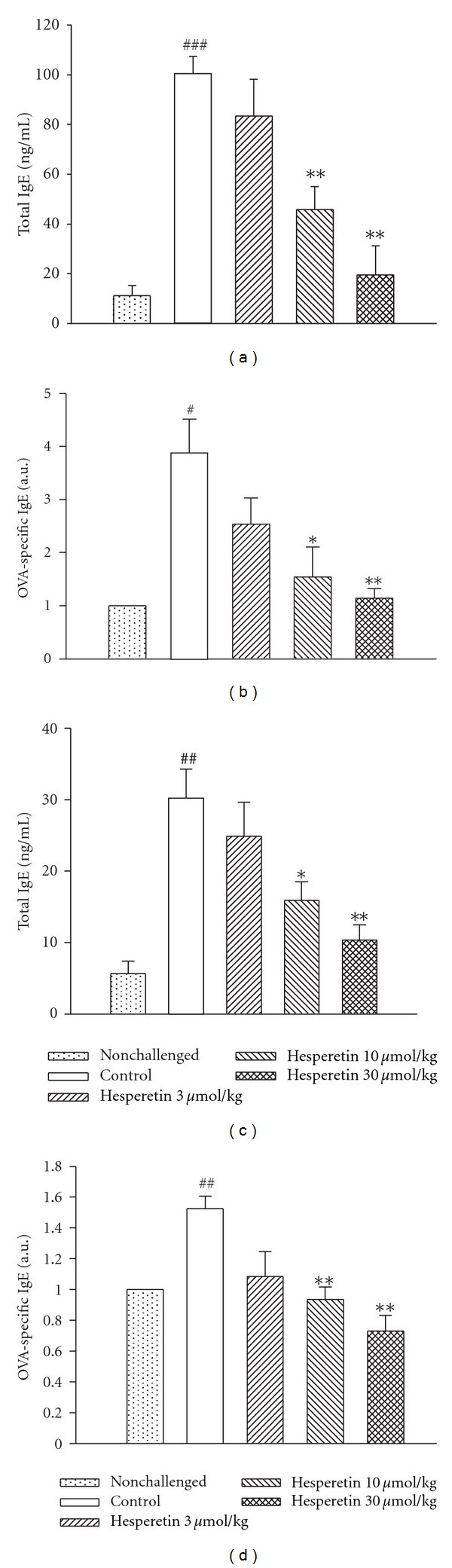

3.6. Suppression of IgE in the Serum and BALF

Levels of total and OVA-specific IgE in the BALF and serum of control sensitized and challenged mice were significantly enhanced compared to those of non-challenged mice. For example, Hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently and significantly suppressed these enhancements (Figures 4(a), 4(b), 4(c), and 4(d)).

Figure 4.

Effects of hesperetin (3 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) on total IgE (a, c) and ovalbumin-specific IgE (b, d) levels in bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (a, b) and serum (c, d) of sensitized mice which had received aerosolized methacholine (6.25 ~ 50 mg/mL) 2 days after primary allergen challenge. # P < 0.05, ## P < 0.01 and ### P < 0.001, compared to the nonchallenged group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, compared to the control (vehicle) group. Each value represents the mean ± SEM. The number of mice in each group was 10.

3.7. No Effect on Xylazine/Ketamine-Induced Anesthesia

The durations of xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia in control (vehicle) mice of the Ro 20-1724- and hesperetin-treated groups were 21.0 ± 2.5 (n = 10) and 22.1 ± 2.2 min (n = 10), respectively. Ro 20-1724 (0.01 ~ 1 μmol/kg, s.c.) dose-dependently shortened the duration, and at doses of 0.1 and 1 μmol/kg (s.c.) significantly shortened the duration (Figure 5(a)). In contrast, hesperetin (10 ~ 100 μmol/kg, s.c.) did not significantly influence the duration (Figure 5(b)).

Figure 5.

Effects of subcutaneously administered Ro 20-1724 (a) and hesperetin (b) on the duration of xylazine (10 mg/kg, i.p.)/ketamine-induced (70 mg/kg, i.p.) anesthesia in mice. Ro 20-1724 was administered 0.25 h and hesperetin 1 h before anesthesia. **P < 0.01, compared to the vehicle (control). Each value represents the mean ± SEM. The number of mice in each group was 10.

4. Discussion

Allergic asthma is a chronic respiratory disease characterized by AHR, mucus hypersecretion, bronchial inflammation, and elevated IgE levels. Th2 cells, together with other inflammatory cells such as eosinophils, B cells, and mast cells were proposed as critical to the initiation, development, and chronicity of this disease [22]. One hypothesis emphasizes an imbalance in Th cell populations favoring expression of Th2 over Th1 cells. Cytokines released from Th2 cells are IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-9, and IL-13, and those from Th1 cells are IL-2, IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α [23, 24]. In the present results, hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced P enh values at 50 mg/mL MCh (Figure 3(a)) suggesting that it significantly suppresses AHR. All types of inflammatory cells examined, including total inflammatory cells, macrophages, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils in the BALF of sensitized and challenged mice were reduced (Figure 3(b)). Hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) also suppressed levels of IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IFN-γ, and TNF-α (Figure 3(c)). These results suggest that hesperetin suppresses both Th1 and Th2 cells which are respectively implicated in autoimmune and atopic diseases [25].

IL-4 and IL-13 were shown to induce AHR in mouse asthma models [26, 27]. IL-4 has three primary effects. First, IL-4 promotes B cell differentiation to plasma cells that secrete antigen-specific IgE antibodies. Second, IL-4 promotes mast cell proliferation. Third, increased IL-4 upregulates endothelial cell expression of adhesion molecules for eosinophils [28]. IL-5 mobilizes and activates eosinophils, leading to the release of a major basic protein, cysteinyl-leukotriene, and eosinophil peroxidase that contribute to tissue damage and AHR [27, 29]. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ (p110δ) was shown to play a crucial role in the development, differentiation, and antigen receptor-induced proliferation of mature B cells [30, 31], and inhibition of p110δ attenuates allergic airway inflammation and AHR in a murine asthma model [30, 32]. In addition, IL-4 and IL-13 are important in directing B cell growth, differentiation, and secretion of IgE [33]. In addition, hesperetin (10 ~ 30 μmol/kg, i.p.) dose-dependently and significantly suppressed total and OVA-specific IgE levels in the BALF and serum of sensitized and challenged mice, suggesting that hesperetin has immunoregulatory and antiallergic asthmatic effects. The results support the recent finding that orally administered hesperidin (hesperetin-7-rutinoside or hesperetin-7-rhamnoglucoside), inhibited inflammatory cell infiltration and mucus hypersecretion in a murine model of asthma [34].

Hesperetin has been reported to selectively inhibit PDE4 activity in our previous report [10], and in the present results, it was revealed to competitively inhibit PDE4 activity. Selective PDE4 inhibitors specifically prevent the hydrolysis of cAMP, a 3′,5′-cyclic nucleotide, and therefore have broad anti-inflammatory effects such as inhibition of cell trafficking and of cytokine and chemokine release from inflammatory cells. The increased cAMP levels induced by these selective PDE4 inhibitors subsequently activate cAMP-dependent protein kinase which may phosphorylate and inhibit myosin light-chain kinase, thus inhibiting contractions [35]. The precise mechanism through which relaxation is produced by this second-messenger pathway is not known, but it may result from decreased intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i). The decrease in [Ca2+]i may be due to reduced influx of Ca2+, enhanced Ca2+ uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticula, or enhanced Ca2+ extrusion through cell membranes [35]. Thus selective PDE4 inhibitors may have bronchodilatory effects. The second-generation PDE4 inhibitors, cilomilast and roflumilast, have reached the clinical trial stage and exhibit some beneficial effects in treating asthma and COPD [36]. The effectiveness of these PDE4 inhibitors may be limited by their clinical potency when using doses that have minimal adverse effects such as headaches, diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain. The PDE4H/PDE4L ratios of cilomilast and roflumilast were, respectively, reported to be 117.8 nM/120 nM (1), and 2.4 nM/0.8 nM (3) [15, 37], which are considerably greater than that (0.01 ~ 0.001) of rolipram [7]. Owing to its adverse effects or lack of efficacy, cilomilast was discontinued for use against asthma after phase II clinical trials in 2003 [36]. In terms of tolerability over 6 months with 15 mg twice daily for COPD in a phase III study, cilomilast was reported to be associated with higher frequencies of diarrhea and nausea than a placebo [36]. Roflumilast was evaluated for asthma and COPD in phase III clinical trials, and was reported to reduce those adverse effects after longer-term treatment at 0.5 mg once daily [36]. Roflumilast, compared to a placebo, was reported to significantly improve the mean pre- and postbronchodilator forced expiratory volumes in 1 s (FEV1) in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD. However, nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, and headaches were more frequent in patients in the roflumilast group. These adverse events were associated with increased patient withdrawal [38, 39]. Recently, roflumilast was approved by the European Commission as an add-on to bronchodilator therapy for maintenance treatment of severe COPD associated with chronic bronchitis in adults with a history of frequent exacerbations. However, the US Food and Drug Administration voted against using roflumilast to treat COPD. The PDE4H/PDE4L ratio of AWD 12-281, another selective PDE4 inhibitor, was reported to be 104 nM/9.7 nM (approximately 11) [40]. AWD 12-281 was undergoing clinical development phase IIa trials for COPD, and was reported to be a unique potential drug for the topical treatment of asthma and COPD [41]. AWD 12-281 was reported to be a very promising drug candidate for treating lung inflammation when administered by inhalation and for treating atopic dermatitis [42]. However, AWD-12-281 was also discontinued in clinical trials for both asthma and COPD owing to a lack of efficacy [43, 44]. Many compounds that are in development will not reach the market as monotherapies unless their emetic liability is reduced [45], although inhaled GSK256066 demonstrated efficacy in trials in asthma [46] and oral apremilast was clinically reported to be effective for treating severe plaque-type psoriasis [47]. PDE4 subtypes (A ~ D) may be considered for drug development of new PDE4 inhibitors. PDE4D inhibition in nontarget tissues promotes emesis, since PDE4D knock-out mice showed reduction of xylazine/ketamine-triggered anesthesia which is used as a surrogate marker for emesis in mice, a nonvomiting species [21]. Recently, small-molecule allosteric modulators of PDE4D that do not completely inhibit enzymatic activity were reported to reduce emesis and have therapeutic benefits of a brain distribution, for such entities as Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, schizophrenia, and depression [48]. In contrast to PDE4D, selective inhibition of PDE4A and/or PDE4B in proinflammatory and immune cells is believed to evoke the therapeutically desired effects of these drugs [49]. Cilomilast has a higher potency for PDE4D compared to PDE4A and PDE4B, while roflumilast is non-selective for these four PDE4 subtypes with similar degrees of inhibition [50]. There is no literature about AWD 12-281′s inhibition of PDE4 subtypes until now. However, whether hesperetin selectively inhibits the PDE4 subtype also needs to be further investigated.

In the present results, the PDE4H/PDE4L ratio of hesperetin was calculated to be >11, which is greater than that of AWD 12-281. In addition, hesperetin did not influence xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia. However, Ro 20-1724, a selective PDE4 inhibitor, reversed the anesthesia. The reversing effect may occur through presynaptic α 2-adrenoceptor inhibition [51], because MK-912, an α 2-adrenoceptor antagonist, was reported to reverse xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia in rats [52] and trigger vomiting in ferrets [51]. In contrast, clonidine, an α 2-adrenoceptor agonist, prevented emesis induced by PDE4 inhibitors in ferrets [51]. The present results also suggest that hesperetin may have few or no adverse effects, such as nausea, vomiting, and gastric hypersecretion.

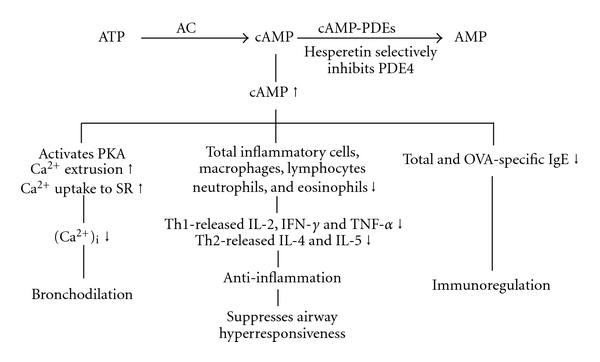

In conclusion, hesperetin exerted anti-inflammatory effects, including suppression of AHR, and reduced expressions of inflammatory cells and cytokines in a murine model of allergic asthma. However, hesperetin did not influence xylazine/ketamine-induced anesthesia suggesting that hesperetin has few or no emetic effects. Thus, the rationales for ameliorating allergic asthma and COPD by hesperetin are antiinflammation, immunoregulation, and bronchodilation resulted from PDE4 inhibition and are summarized in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Mechanisms of action of hesperetin. Hesperetin selectively inhibits PDE4 activity and results in an increase in cAMP, which activates cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and increases calcium extrusion from the intracellular space and uptake to sarcoplasmic reticula (SR). Therefore, hesperetin largely decreases the concentration of intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) and results in bronchodilation. The increase in cAMP also has anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects. AC: adenylate cyclase; Th: T-helper cells; Ig: immunoglobulin; IL: interleukin; IFN: interferon; TNF: tumor necrosis factor. Up and down arrows, respectively, indicate increases and decreases.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by a Grant (NSC97-2320-B-038-015) from the National Science Council, Taiwan.

Abbreviations

- AHR:

Airway hyperresponsiveness

- cAMP:

Adenosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate

- cGMP:

Guanosine 3′,5′ cyclic monophosphate

- COPD:

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- DMSO:

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDTA:

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- HARBSs:

High-affinity rolipram-binding sites

- IFN:

Interferon

- Ig:

Immunoglobulin

- IL:

Interleukin

- Ki:

Dissociation constant for inhibitor binding

- MCh:

Methacholine

- PBS:

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PDE:

Phosphodiesterase

- PDE4H:

High affinity for PDE4

- PDE4L:

Low affinity for PDE4

- P enh:

Enhanced pause

- PMSF:

Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride

- Ro 20-1724:

4-(3-butoxy-4-methoxybenzyl)-2-imidazolidinone

- TCM:

Traditional Chinese medicine

- Th:

T-helper

- TNF:

Tumor necrosis factor.

References

- 1.Lee ME, Markowitz J, Lee JO, Lee H. Crystal structure of phosphodiesterase 4D and inhibitor complex. FEBS Letters. 2002;530(1–3):53–58. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03396-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torphy TJ, Cieslinski LB. Characterization and selective inhibition of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozymes in canine tracheal smooth muscle. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990;37(2):206–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapui Z, Schaeffer P, Mikus EG, et al. Experimental studies on guanosine 3’,5’-cyclic monophosphate levels and airway responsiveness of the novel phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor SR 265579 in guinea-pigs. Arzneimittel-Forschung. 1999;49(8):685–693. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Boer J, Philpott AJ, Van Amsterdam RGM, Shahid M, Zaagsma J, Nicholson CD. Human bronchial cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isoenzymes: biochemical and pharmacological analysis using selective inhibitors. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;106(4):1028–1034. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14451.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silver PJ, Hamel LT, Perrone MH, Bentley RG, Bushover CR, Evans DB. Differential pharmacologic sensitivity of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase isozymes isolated from cardiac muscle, arterial and airway smooth muscle. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1988;150(1-2):85–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90753-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim E, Chun HO, Jung SH, et al. Improvement of therapeutic index of phosphodiesterase type IV inhibitors as anti-asthmatics. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2003;13(14):2355–2358. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00405-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giembycz MA. Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors and the treatment of asthma: where are we now and where do we go from here? Drugs. 2000;59(2):193–212. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200059020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yen KY. Pharmacology of Common Chinese Medicine (III) Taipei, Taiwan: National Research Institute of Chinese Medicine; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knekt P, Kumpulainen J, Järvinen R, et al. Flavonoid intake and risk of chronic diseases. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2002;76(3):560–568. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.3.560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko WC, Shih CM, Lai YH, Chen JH, Huang HL. Inhibitory effects of flavonoids on phosphodiesterase isozymes from guinea pig and their structure-activity relationships. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2004;68(10):2087–2094. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gu X, Zhou L, Du Q, et al. Hesperetin inhibits the maturation and function of monocyte-derived dendritic cells from patients with asthma. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2009;2(3):509–513. doi: 10.3892/mmr_00000129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joseph Thompson W, Appleman MM. Multiple cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activities from rat brain. Biochemistry. 1971;10(2):311–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schneider HH, Schmiechen R, Brezinski M, Seidler J. Stereospecific binding of the antidepressant rolipram to brain protein structures. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1986;127(1-2):105–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(86)90210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry. 1976;72(1-2):248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao Y, Zhang HT, O’Donnell JM. Inhibitor binding to type 4 phosphodiesterase (PDE4) assessed using [3H]piclamilast and [3H]rolipram. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;305(2):565–572. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.47407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reeves ML, Leigh BK, England PJ. The identification of a new cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase activity in human and guinea-pig cardiac ventricle. Implications for the mechanism of action of selective phosphodiesterase inhibitors. Biochemical Journal. 1987;241(2):535–541. doi: 10.1042/bj2410535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanehiro A, Ikemura T, Mäkelä MJ, et al. Inhibition of phosphodiesterase 4 attenuates airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in a model of secondary allergen challenge. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;163(1):173–184. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamelmann E, Schwarze J, Takeda K, et al. Noninvasive measurement of airway responsiveness in allergic mice using barometric plethysmography. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1997;156(3):766–775. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.3.9606031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winterrowd GE, Chin JE. Flow cytometric detection of antigen-specific cytokine responses in lung T cells in a murine model of pulmonary inflammation. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1999;226(1-2):105–118. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00049-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melgert BN, Postma DS, Geerlings M, et al. Short-term smoke exposure attenuates ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in allergic mice. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2004;30(6):880–885. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0178OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robichaud A, Stamatiou PB, Jin SLC, et al. Deletion of phosphodiesterase 4D in mice shortens α2-adrenoceptor-mediated anesthesia, a behavioral correlate of emesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;110(7):1045–1052. doi: 10.1172/JCI15506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Busse WW, Lemanske RF., Jr. Asthma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344(5):350–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revets H, Pynaert G, Grooten J, De Baetselier P. Lipoprotein I, a TLR2/4 ligand modulates Th2-driven allergic immune responses. Journal of Immunology. 2005;174(2):1097–1103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vojdani A, Erde J. Regulatory T cells, a potent immunoregulatory target for CAM researchers: the ultimate antagonist (I) Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2006;3(1):25–30. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nek022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cher DJ, Mosmann TR. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. II. Delayed-type hypersensitivity is mediated by TH1 clones. Journal of Immunology. 1987;138(11):3688–3694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taube C, Duez C, Cui ZH, et al. The role of IL-13 in established allergic airway disease. Journal of Immunology. 2002;169(11):6482–6489. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.11.6482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vargaftig BB, Singer M. Leukotrienes mediate murine bronchopulmonary hyperreactivity, inflammation, and part of mucosal metaplasia and tissue injury induced by recombinant murine interleukin-13. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology. 2003;28(4):410–419. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0032OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tucker J, Fanta CH. Integrative inflammation pharmacology: asthma. In: Golan DE, Tashjian AH Jr., Armstrong EJ, Galanter JM, W. Armstrong A, Arnaout RA, et al., editors. Principles of Pharmacology the Pathophysiologic Basis of Drug Therapy. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 695–705. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foster PS, Hogan SP, Ramsay AJ, Matthaei KI, Young IG. Interleukin 5 deficiency abolishes eosinophilia, airways hyperreactivity, and lung damage in a mouse asthma model. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;183(1):195–201. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clayton E, Bardi G, Bell SE, et al. A crucial role for the p110δ subunit of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in B cell development and activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2002;196(6):753–763. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okkenhaug K, Bilancio A, Farjot G, et al. Impaired B and T cell antigen receptor signaling in p110δ PI 3-kinase mutant mice. Science. 2002;297(5583):1031–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1073560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee KS, Lee HK, Hayflick JS, Lee YC, Puri KD. Inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase δ attenuates allergic airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in murine asthma model. FASEB Journal. 2006;20(3):455–465. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5045com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emson CL, Bell SE, Jones A, Wisden W, McKenzie ANJ. Interleukin (IL)-4-independent induction of immunoglobulin (Ig)E, and perturbation of T cell development in transgenic mice expressing IL-13. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1998;188(2):399–404. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei D, Ci X, Chu X, Wei M, Hua S, Deng X. Hesperidin suppresses ovalbumin-induced airway inflammation in a mouse allergic asthma model. doi: 10.1007/s10753-011-9295-7. Inflammation. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Westfall DP, Gerthoffer WT, Webb RC. Vasodilators and nitric oxide synthase. In: Brody TM, Larner J, Minneman KP, editors. Human Pharmacology Molecular to Clinical. St. Louis, Mo, USA: Mosby; 1998. pp. 239–247. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lipworth BJ. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet. 2005;365(9454):167–175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17708-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hatzelmann A, Schudt C. Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory potential of the novel PDE4 inhibitor roflumilast in vitro. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;297(1):267–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabbri LM, Calverley PM, Izquierdo-Alonso JL, et al. Roflumilast in moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with longacting bronchodilators: two randomised clinical trials. The Lancet. 2009;374(9691):695–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calverley PM, Rabe KF, Goehring UM, Kristiansen S, Fabbri LM, Martinez FJ. Roflumilast in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomised clinical trials. The Lancet. 2009;374(9691):685–694. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Draheim R, Egerland U, Rundfeldt C. Anti-Inflammatory potential of the selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor N-(3,5-Dichloro-pyrid-4-yl)-[1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-indole-3-yl] -glyoxylic acid amide (AWD 12–281), in human cell preparations. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2004;308(2):555–563. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.059097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kuss H, Hoefgen N, Johanssen S, Kronbach T, Rundfeldt C. In vivo efficacy in airway disease models of N-(3,5-dichloro-pyrid-4-yl)-[1-(4-fluorobenzyl)-5-hydroxy-indole-3-yl] -glyoxylic acid amide (AWD 12–281), a selective phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor for inhaled administration. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;307(1):373–385. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoppmann J, Bäumer W, Galetzka C, Höfgen N, Kietzmann M, Rundfeldt C. The phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor AWD 12-281 is active in a new guinea-pig model of allergic skin inflammation predictive of human skin penetration and suppresses both Th1 and Th2 cytokines in mice. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2005;57(12):1609–1617. doi: 10.1211/jpp.57.12.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giembycz MA. Can the anti-inflammatory potential of PDE4 inhibitors be realized: guarded optimism or wishful thinking? British Journal of Pharmacology. 2008;155(3):288–290. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pagès L, Gavaldà A, Lehner MD. PDE4 inhibitors: a review of current developments (2005–2009) Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 2009;19(11):1501–1519. doi: 10.1517/13543770903313753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Higgs G. Is PDE4 too difficult a drug target? Current Opinion in Investigational Drugs. 2010;11(5):495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singh D, Petavy F, Macdonald AJ, Lazaar AL, O’Connor BJ. The inhaled phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor GSK256066 reduces allergen challenge responses in asthma. Respiratory Research. 2010;11:26–34. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gottlieb AB, Strober B, Krueger JG, et al. An open-label, single-arm pilot study in patients with severe plaque-type psoriasis treated with an oral anti-inflammatory agent, apremilast. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2008;24(5):1529–1538. doi: 10.1185/030079908x301866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burgin AB, Magnusson OT, Singh J, et al. Design of phosphodiesterase 4D (PDE4D) allosteric modulators for enhancing cognition with improved safety. Nature Biotechnology. 2010;28(1):63–70. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin SL, Richter W, Conti M. Insights into the physiological functions of PDE4 from knockout mice. In: Beavo JA, Francis SH, Houslay MD, editors. Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases in Health and Disease. Boca Raton, Fla, USA: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fan Chung K. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors in airways disease. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2006;533(1–3):110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robichaud A, Savoie C, Stamatiou PB, Tattersall FD, Chan CC. PDE4 inhibitors induce emesis in ferrets via a noradrenergic pathway. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40(2):262–269. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Robichaud A, Savoie C, Stamatiou PB, et al. Assessing the emetic potential of PDE4 inhibitors in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;135(1):113–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]