Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains an important cause of acute and chronic liver disease globally and in the United States. An encouraging trend is that the incidence of acute hepatitis B in the United States declined as much as 80% between 1987 and 2004, attributable to effective vaccination programs as well as universal precautions in needle use and in healthcare in general. While encouraging, these decreases in acute infections have not translated into diminished prevalence or burden of chronic HBV infection. The prevalence for HBV in the United States has been estimated to be approximately 0.4%. However, these estiamtes have been based upon surveys conducted in samples in which population groups with high prevalence of HBV infection, namely foreign-born minorities, were underrepresented. Voluntary screening data indicate prevalence in excess of 15% in some of these groups. Recent immigration trends suggest a substantial increase in the number of Americans with chronic HBV infection. This trend is reflected in the health and economic burden associated with HBV infection. The number of outpatient visits and hospitalizations for a HBV-related diagnosis increased several fold during the 1990s. Similarly, the total charges for hospitalizations have been estimated to have increased from $357 million in 1990 to $1.5 billion in 2003. Most recent data indicate that death and liver transplant waitlist registration for HBV-related liver disease, which had been increasing, have now reached a plateau or started to decline. This encouraging trend might be attributable to recent advances in treatment for HBV infection; however, to the extent that the number of Americans living with chronic HBV is growing, careful clinical monitoring and continued epidemiologic surveillance remain important.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, epidemiology, cirrhosis, chronic hepatitis, maternal infant transmission, injection drug use, sexual transmission

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is an important cause of acute and chronic liver disease in the United States and globally.1 The term, “disease burden,” encompasses several aspects of the impact of a disease on the health of a population, including: (1) the frequency of the disease, as measured by incidence and prevalence; (2) its effect on longevity, such as mortality rate and years of life lost because of premature death; (3) morbidity, including impairment in health status and quality of life as well as the need for health care; and (4) finance, including direct health care expenditures and indirect costs related to lost income from premature death or disability.2, 3 Although accurate data are sparse to address all of these parameters for HBV-related disease, available information about its epidemiology and burden is summarized in the following sections.

Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus

HBV is transmitted by percutaneous and mucous membrane exposures to infectious body fluids, such as serum, semen, and saliva.4 Perinatal transmission is thought to be the major route by which HBV infection is perpetuated in endemic populations. Children born to HBsAg-positive mothers who do not become ‘vertically’ infected during the perinatal period remain at risk of infection during early childhood.5 Although the exact mechanism by which this ‘horizontal’ transmission of HBV occurs in children is not completely understood, contacts involving contaminated environmental objects may an important role.

Among adults, high-risk sexual activity is one of the most frequent routes of transmission for HBV.6 Historically, male homosexual contacts have been associated with a high risk for HBV infection. More recently, heterosexual transmission is the most common cause of acute HBV infection in adults.7 Transmission of HBV via transfusion of blood and plasma-derived products has been essentially eliminated through donor screening and viral inactivation procedures. However, transmission of HBV may continue to occur in other health care setting.8 For example, non-adherence to isolation guidelines in a hemodialysis unit or direct person-to-person exposure (e.g., surgeon- or dentist-to-patients) may transmit HBV.

The distinction between HBV infection acquired in early childhood and that in adulthood is important because the subsequent course of HBV infection differs substantially.9 Infection acquired in children usually leads to chronic life-long infection in without a clinically apparent acute hepatitis. This pattern occurs most commonly in areas of the world in which HBV is endemic. Infection acquired in adulthood, in contrast, frequently results in symptomatic acute hepatitis followed by clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the majority of patients. In a low prevalence setting, such as the general population of the United States, most persons with acute HBV infection are adults and chronic infection develops in only 1% to 5% of the newly infected.10

These two patterns of HBV infection have important implication in measuring the burden of HBV-related disease in the population. If HBV transmission occurs early in life (<5 years of age), most infections will be chronic and the disease burden is primarily that of long-term consequences of the infection. When HBV transmission mostly occurs during adulthood, the majority of the burden is related to the harms of symptomatic acute hepatitis, including fulminant hepatitis which occurs in 0.1% to 0.5% of those with acute HBV infection.

Incidence and Prevalence of HBV Infection in the United States

Disease frequency may be measured either by the pool of existing cases and/or by the occurrence of new cases. The former (prevalence) describes what proportion of the population has the disease in question at a specific point in time, whereas the latter (incidence) is measured by the frequency of new cases developing during a defined time period. From the standpoint of HBV infection, prevalence is a more relevant measure in endemic populations in which babies and children acquire HBV and are left with chronic life-long infection, whereas in other settings, incidence is a more appropriate measure of disease burden, as most of the impact of HBV infection is a result of acute hepatitis.

HBV is a reportable infectious disease in the United States and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been monitoring its incidence for several decades.7 National surveillance is conducted for acute viral hepatitis B, defined by IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (IgM anti-HBc) or newly found HBsAg. In addition, nationwide reporting of perinatal HBV infection was implemented in 2001. In January 2003, chronic HBV infection was added to the list of nationally notifiable conditions.

Incidence of HBV Infection in the United States

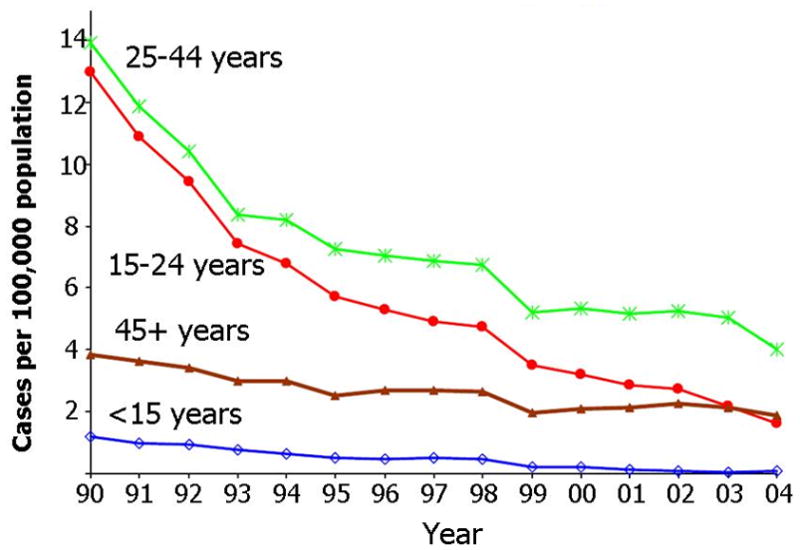

Based on data from CDC, the incidence of acute hepatitis B in the United States has declined steadily since the late 1980s.6 Between 1987 and 2004, the incidence of acute hepatitis B declined 80%, from 10.7 per 100,000 (25,916 cases reported) to 2.1 per 100,000 (6,212 cases reported).7 Figure 1 summarizes acute hepatitis B incidence by age group. The highest incidence of acute hepatitis B has been seen among persons 25–44 years of age (4.0/100,000 persons in 2004) and the lowest among children less than 15 years of age (0.1/100,000 in 2004). Over time, the incidence decreased in all age groups with the greatest proportional decline occurring among age groups <15 years (95% decline) and 15–24 years (87% decline). Although less dramatic, substantial decreases were also seen among older persons with a 71% and 51% decrease in rates observed for 25–44 year-old and 45+ year-old groups respectively. In general, the incidence of acute hepatitis B is higher in men than in women (2.7/100,000 versus 1.6/100,000 in 2004).

Figure 1.

Incidence of acute hepatitis B per 100,000 population in the United States by year (1990–2004) and age group. (Reproduced from reference 7, permission waived by CDC).

Figure 2 illustrates the incidence of acute hepatitis B by race. Although HBV infection is commonly associated with Asian/Pacific Islander races, the incidence acute hepatitis B in the United States has historically been the highest among non-Hispanic blacks. The decline in HBV incidence over time affected all racial and ethnic groups. By 2004, racial disparity in the incidence of HBV infection was essentially eliminated. While numerically the incidence in non-Hispanic blacks remained nearly three times higher than that in other groups, nevertheless, the occurrence of acute hepatitis B among non-Hispanic blacks had been reduced to an historic low (2.9/100,000 in 2004).

Figure 2.

Incidence of acute hepatitis B per 100,000 population (gender adjusted) in the United States by year (1990–2004) and racial group. (Reproduced from reference 7, permission waived by CDC). Abbreviations: AI/AN, American Indian and Aboriginal Native; API, Asian or Pacific Islander.

The reduction in HBV incidence in the United States may be attributed to several measures implemented since 1991.4 Elements of this strategy included (1) universal vaccination of infants beginning at birth, (2) prevention of perinatal HBV infection through routine screening of all pregnant women for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and the provision of immunoprophylaxis to infants born to HBsAg-positive women (3) routine vaccination of previously unvaccinated children and adolescents; and (4) vaccination of previously unvaccinated adults at increased risk for infection. The last include health care workers, dialysis patients, household contacts and sex partners of persons with chronic HBV infection, recipients of certain blood products, persons with a recent history of multiple sex partners or a sexually transmitted disease, men who have sex with men, and injection drug users.

Prevalence of HBV

The prevalence of viral hepatitis infection in the US population at large has been estimated using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES), a series of cross-sectional national surveys designed to provide representative health measures and conditions among civilian non-institutionalized individuals in the United States.11, 12 HBV data in the NHANES surveys indicate the prevalence of HBsAg-positive individuals is low (0.33% in 1976–1980 and 0.42% in 1988–1994).11, 13 More recent unpublished data from 2005–2006 are similar (0.30%).14 These estimates project to approximately 800,000 Americans with on-going infection with HBV. Since the NHANES data are designed to be representative of the US general population, the survey data have important limitations for estimating HBV prevalence. The NHANES samples did not include statistically valid samples from populations in which HBV is most common, such as Asians, Pacific Islander and Alaskan Natives.6, 15 In addition, the surveys by design excluded institutionalized, homeless, or incarcerated individuals, all of whom are expected have increased prevalence of HBV infection. Thus, it is widely held that NHANES data underestimate of the true prevalence of HBV in the United States.

The importance of taking into account individuals not represented in the NHANES surveys has been underlined by several studies. In a report of a community cohort with HBV, out of 191 residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota diagnosed with HBV infection between 1994 and 2000, more than a half (53%) were Asians while whites accounted for only 13%.16 Most of non-white individuals had been born outside the United States including nearly all Asian (99%) and African (91%) patients. These data were further corroborated by a recent study that measured HBV prevalence among refugees arriving in Minnesota and enrolled in a health assessment program.17 Between 1998 and 2001, 12,389 refugees were evaluated. The highest HBV prevalence was seen among African refugees (8.4%), followed by Asian (5.1%) and European (3.1%) counterparts. As shown in Figure 3, the peak prevalence in excess of 10% was seen in adults between 20 and 40 years of age.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of HBsAg among 12, 389 refugees arriving in Minnesota between 1998 and 2001 by continent of origin and age group (decade). Overall percentage and numbers tested given in the legend. Data from reference 17.

Another survey assessed the prevalence of chronic HBV infection among Asian/Pacific Islander populations living in New York City.18 Of 925 survey participants who reported not having been tested previously for HBV infection, 137 (14.8%) were HBsAg-positive, whereas another 496 (53.6%) had evidence of resolved HBV infection. Chronic HBV infection was more common among males (19.7%) than females (8.7%). Prevalence of chronic HBV infection varied by country of birth, from 21.4% among those born in China to 4.6% among those born in South Korea and 4.3% among those born in other Asian countries.

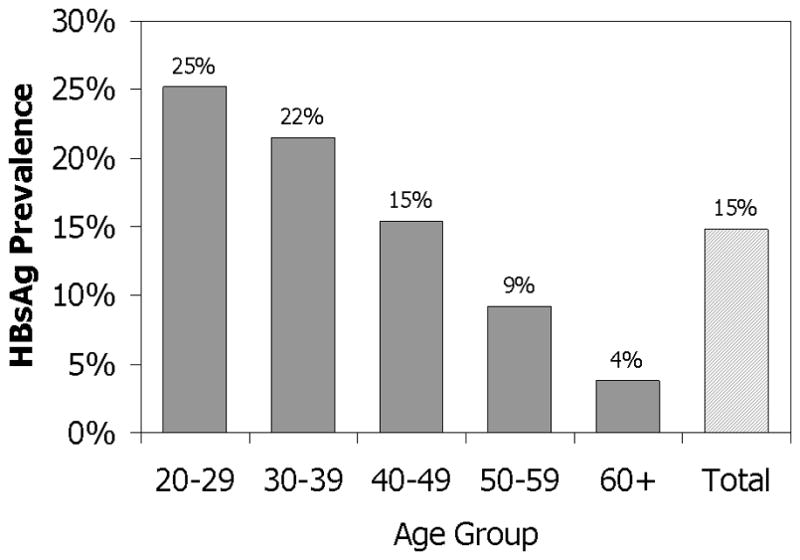

One of the most striking elements of the survey results was the prevalence of HBV by age group. Consistent with the Minnesota refugee data, the highest prevalence was seen in young adults. In Figure 4, among respondents aged between 20 and 29, HBV prevalence was 25.2%, followed by 21.5% among those 30–39 years of age. The prevalence progressively decreased according to the age. The majority of the respondents in the survey were immigrants with 46% having lived in the United States for less than 10 years. To the extent that this survey was voluntary and not based on population-based sampling, a certain degree of self-selection is undoubtedly present. Incidentally, the prevalence of HBV infection was higher among respondents who reported to be uninsured (17% versus 10% among those with insurance). Of all the respondents, 77% reported having no health insurance.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of HBsAg among Asian-Pacific Islander Populations in New York City by age group. Data from reference 18.

Results of these and other screening programs in Atlanta, Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, and California indicate that the prevalence of HBV infection is disproportionately high (10% to 15%) among Asians, Pacific Islanders and other immigrant populations.19, 20 These statistics are not surprising given the geographic distribution of HBV in the world and the recent pattern of immigration. In order to accurately gauge the disease prevalence in immigrant groups, systematic screening would be necessary. However, screening for HBV is not universally required for immigrants, as it is for human immunodeficiency virus infection or tuberculosis. Given the lack of data, estimates have been made based on number of immigrants and the prevalence of HBV in their originating countries. A recent study estimated the number of immigrants living in the United States in 2008 based on the US Census data and computed the number of prevalent cases with HBV. Out of the estimated 41 million Americans born elsewhere, 1.5 million (range: 0.9 to 2.2 million) were estimated to have HBV infection, including 863,000 from Asia, 291,000 from Central America and the Caribbean, 196,000 from Africa and 173,000 from Eastern Europe and elsewhere.21 When these estimates are compared with the NHANES data, the true prevalence of HBV infection in the United States might be several times higher than what was projected in the US general population.

Burden of Liver Disease from HBV Infection in the United States

HBV infection incurs significant health burden in a number of disease states: (1) acute hepatitis, which may range from symptomatic cases requiring in- and out-patient care to fulminant cases leading to liver failure and death unless liver transplantation is performed; (2) chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis which are largely asymptomatic, yet requires monitoring and treatment as indicated, as well as screening for hepatocellular carcinoma; (3) decompensated cirrhosis which is usually associated with significant reduction in quality of life, substantial risk of mortality, and increased resource utilization from frequent in- and out-patient care; and (4) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which has extremely high risk of mortality and incur significant health care utilization for curative or palliative treatment. When all of these are taken into account, the total burden of HBV-related liver disease is likely substantial; however, to date, there are only limited data about the burden of liver disease associated with HBV infection in the United States.

A recent report on the burden of digestive diseases used the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and estimated that outpatient visits for a HBV-related diagnosis in the United States occurred at a rate less than 100 visits per 100,000 in 1996, which increased by at least 4 fold to greater than 400 visits per 100,000 by 2004.22 The National Hospital Discharge Survey data indicate a similar increase in discharges with a HBV diagnosis: in 1992, the rate of hospitalization for a HBV-related illness was 5 per 100,000, which increased to more than 20 per 100,000 in 2002.22 These data strongly suggest that the number of patients with HBV requiring in- and out-patient care increased substantially during the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Figure 5 summarizes results of an analysis of hospital discharges with a HBV diagnosis based on another data set, the Nationwide Inpatient Sample of the Healthcare Utilization Project database (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD). In the figure, the taller bars represent all hospitalizations with any HBV diagnosis, whereas the shorter ones indicate hospitalizations in which HBV infection was the principal diagnosis or was associated with a diagnosis indicative of liver complication (e.g., ascites, HCC). There was a similar magnitude of increase (approximately 4-fold) in either type of HBV hospitalizations between 1990 and 2006. The increase was linear up to 2003 or 2004, when a plateau seems to have reached. Again, these increases in hospital resource utilization for liver disease related to HBV suggest increased prevalence of illnesses related to chronic HBV infection in the United States during the 1990s and early 2000s.

Figure 5.

Number of hospital discharges and total charges (in 2006 adjusted U.S. dollars) with a hepatitis B-related illness in the United States by year (1990–2006). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, unpublished data. Error bars indicate the upper half of 95% confidence interval.

As expected, these increases in hospital resource utilization were accompanied by substantial health economic expenditures. The line in Figure 5 estimates the total charges by hospitalizations (exclusive of physician charges) for HBV in the United States. The total charges, inflation-adjusted to 2006 US$, increased from $357 million in 1990 to $1.5 billion in 2003 and then formed a plateau at $1.3 billion. These estimates appear much higher than what was reported in the recently published “Burden of Digestive Diseases in the United States”, which estimated the direct cost of hepatitis B in 2004 at $205 million and indirect cost at $253 million.23 The discrepancy is likely from different methods of allocating costs. For example, in the data presented in Figure 5, the total charges of a hospitalization classified to be liver-related were attributed to hepatitis B, whereas only 20% of charges were thought to be for hepatitis B in Burden of Digestive Diseases report, if HBV was a secondary diagnosis. Another potentially large health expenditure related to hepatitis B is anti-HBV drugs. According to market research data, the anti-HBV prescription market (exclusive of interferon products) grew in a linear fashion from $38 million in the first quarter of 2006 to $82 million in the second quarter of 2008. This represents approximately 13% increase per quarter and more than 50% increase annually.24

Figure 6 summarizes the longitudinal trend in the number of waitlist registrants for liver transplantation for HBV-related indications.25 Waitlist registration for acute liver failure, end stage liver disease and HCC increased steeply in mid-1990’s, coinciding with widespread adoption of hepatitis B immune globulin for prevention of recurrent hepatitis B of the transplanted liver.26 Since then, waitlist registration for end stage liver disease reached a peak in 2000, followed by a sharp decrease. There was a 37% reduction in waitlist registration between 2000 and 2006. In contrast, waitlist registration for HCC remained on an incline throughout. Finally, waitlist registration from fulminant liver failure from HBV infection peaked in 1995 and then decreased, mirroring the trend in the incidence of acute hepatitis B. The reason for the recent decline in the waitlist registration for end-stage-liver-disease may be multi-factorial, including implementation of a new liver allocation system based upon the Model for End Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. The new allocation system assigned a high level of priority to patients with a high risk of death from liver failure and other reasons such as HCC and its implementation in 2002 led to an overall reduction in waitlist registration.27 It is also feasible that antiviral agents introduced in the mid- to late- 1990s may have decreased the number of patients developing complications of end stage liver disease due to HBV.

Figure 6.

Number of patients placed on the liver transplantation waitlist by year for hepatitis B-related indications in the United States. Registrants for end-stage cirrhosis have been declining (−37%) while those for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have been rising (+146%). Data from reference 25.

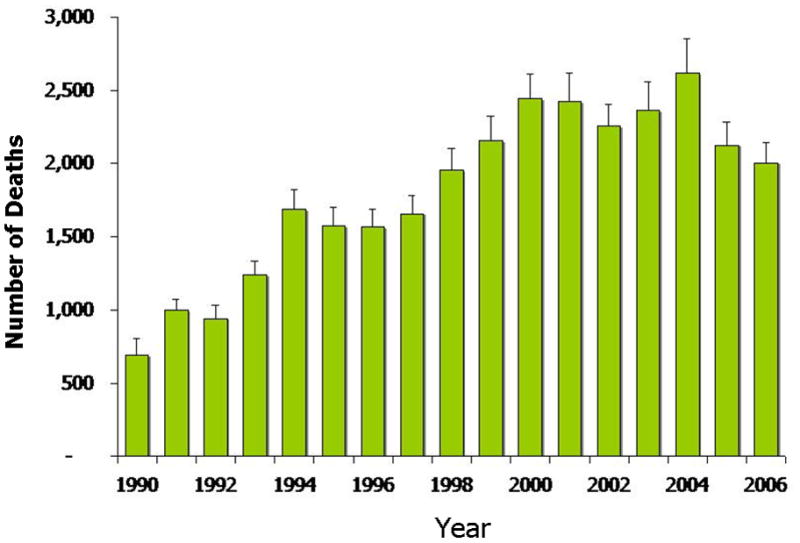

According to an analysis of the national death registry, the age-adjusted mortality rate for HBV-related illness increased throughout the 1980s and early 1990s from 0.2 per 100,000 to 0.8 per 100,000.28 This increase was followed by a relative plateau and then a decline starting in 1999. As of 2004, the mortality rate was approximately 0.6 per 100,000.22 These figures are again corroborated by the Nationwide Inpatient Sample data; there was a rise in the number of in-hospital deaths from less than 700 in 1990 to almost 2,500 in 2000 (Figure 7). Since then the trend was reversed and the number of deaths decreased to 2,003 in 2006. These data about liver transplant waitlist registration and death indicate that there has been a recent decrease in the number of patients who experience liver failure and die or require liver transplantation. While this obviously is an encouraging trend, extrapolation of these declines into the future is not necessarily warranted. To the degree that there are many indications that the number of Americans with chronic HBV infection has been increasing, as these (recent immigrant) individuals age and their disease progress, these downward trends may reverse. Regardless of whether antiviral drugs have had a role in the decline in liver failure and mortality, there is little doubt that an increasing number of Americans are taking anti-HBV agents and the eventual fate of these individuals remains to be seen.

Figure 7.

Number of in-hospital deaths due to hepatitis B-related causes in the United States by year (1990–2006). Nationwide Inpatient Sample, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, unpublished data. Error bars indicate the upper half of 95% confidence interval.

Needs for Future Research

From the standpoint of epidemiology, the greatest need for research is in accurate measurement of prevalence of HBV infection in the United States. The current estimates are primarily based upon the NHANES survey, which does not address the population groups in which HBV is prevalent. Data from other ad-hoc screening surveys are limited, because they were derived from individuals who participated in the surveys voluntarily and it is difficult to gauge whether the data are generalizable. NHANES-type surveys that employ probabilistic sampling of the target population (e.g., Asian immigrants) that will generate data that are generalizable to the population will be very helpful not only to assess the current burden of HBV infection in the population but also to monitor the impact of public health interventions.

With regard to the impact of HBV infection on health, mortality and health service utilization, statistics based on public source data will remain important. However, those data sets, including death registries and hospital discharge summaries, lack the clinical details that are necessary for complete understanding of what is going on with HBV infection in the population, such as impact of wide-spread application of antiviral therapy. Large cohort studies that include representative samples of the population and incorporate detailed clinical information may complement the information from public health sources. In that regard, studies such as the NIDDK-sponsored hepatitis B clinical research network may represent an important step in the right direction.

Conclusions

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) remains an important cause of acute and chronic liver disease in the United States. The incidence of new infections with HBV has decreased dramatically in the past two decades, largely due to widespread vaccination programs in children as well as safer needle-using practices and universal precaution in healthcare as well as exclusion of blood donors with infection. These decreases in acute infections have not translated into diminished prevalence or burden of chronic HBV infection in the United States. The prevalence estimates (approximately 0.4%) for the general population have underestimated the true burden of chronic HBV infection and recent data indicate that migration of people with existing HBV infection has had important impact on the prevalence of HBV infection. The burden of HBV infection, as measured by in- and out-patient healthcare utilization, waitlist registration for liver transplantation, and mortality related to HBV infection, increased substantially throughout the 1990s and leveled off or declined more recently. These data suggest that a growing number of Americans are living with chronic HBV and that careful clinical monitoring and continued epidemiologic surveillance are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: Grant support by National Institutes of Health (DK-82843)

Abbrevations

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HBsAg

hepatitis B surface antigen

- IgM anti-HBc

IgM antibody to hepatitis B core antigen

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- CDC

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- NHANES

National Health and Nutrition Survey

- MELD

Model for End Stage Liver Disease

Footnotes

Potential Conflicts of Interest:

Grants: None

Consultant (ad hoc and advisory board): Bristol-Myers-Squibb, Gilead Sciences, Roche

References

- 1.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2004;11(2):97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of disease : a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim WR, Brown RS, Jr, Terrault NA, El-Serag H. Burden of liver disease in the United States: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2002;36(1):227–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alter MJ. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Seminars in Liver Disease. 2003;23(1):39–46. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beasley RP, Hwang LY. Postnatal infectivity of hepatitis B surface antigen-carrier mothers. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1983;147(2):185–90. doi: 10.1093/infdis/147.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anonymous. Incidence of acute hepatitis B--United States, 1990–2002. MMWR. 2004;52(51–52):1252–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Hepatitis Surveillance Report 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2006. pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harpaz R, Von Seidlein L, Averhoff FM, Tormey MP, Sinha SD, Kotsopoulou K, Lambert SB, et al. Transmission of hepatitis B virus to multiple patients from a surgeon without evidence of inadequate infection control.[see comment] New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(9):549–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMahon BJ, Alward WL, Hall DB, Heyward WL, Bender TR, Francis DP, Maynard JE. Acute hepatitis B virus infection: relation of age to the clinical expression of disease and subsequent development of the carrier state. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1985;151(4):599–603. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seeff L, Beebe G, Hoofnagle J, Norman J, Buskell-Bales Z, Waggoner J, Kaplowitz N, et al. A serologic follow-up of the 1942 epidemic of post-vaccination hepatitis in the United States Army. N Engl J Med. 1987;316(16):965–970. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198704163161601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQuillan G, Coleman P, Kruszon-Moran D, Moyer L, Lambert S, Margolis H. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:14–18. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alter M, Moran-Kruszon D, Nainan O, McQuillan G, Gao G, Moyer L, Kaslow R, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1994;341:556–562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous. NHANES 2001–2002 Public Data General Release File Documentation. 2004 [cited 2006 November 19]; Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhanes/nhanes_01_02/general_data_release_doc.pdf.

- 14.Anonymous. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. 2008 [cited 2008 October, 20]; Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhanes/nhanes2005-2006/lab05_06.htm.

- 15.Coleman P, McQuillan G, Moyer L, Lambert S, Margolis H. Incidence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States, 1976–1994: estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:954–9. doi: 10.1086/515696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim WR, Benson JT, Therneau TM, Torgerson HA, Yawn BP, Melton LJ., 3rd Changing epidemiology of hepatitis B in a U.S. community. Hepatology. 2004;39(3):811–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ugwu C, Varkey P, Bagniewski S, Lesnick T. Sero-epidemiology of hepatitis B among new refugees to Minnesota. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2008;10(5):469–74. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anonymous. Screening for chronic hepatitis B among Asian/Pacific Islander populations--New York City, 2005. MMWR - Morbidity & Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(18):505–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guane R, Siu P, Lam K, Kim KE, Warren V, Liu H, Chang MY, et al. Prevalence of HBV and risk of HBV acquisition in hepatitis B screening programs in large metropolitan cities in the US. Hepatology. 2004;40(S1):716A. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong MJ, Hwang SJ. Hepatitis B virus infection in Asian Americans. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 1994;23(3):523–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welch S, Chiang B, Shadday P, Brosgart CL. Estimated prevalence of chronic hepatitis B in foreign-born persons living in the United States by country/region of origin (Abstract) Hepatology. 2008;48(4S):687A. doi: 10.1002/hep.24804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Everhart JE. Viral Hepatitis. In: Everhart JE, editor. Burden of Digestive Diseases in the United States. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2009. pp. 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruhl CE, Sayer B, Byrd-Holt D, Brown DM. Costs of Digestive Diseases. In: Everhart JE, editor. Burden of Digestive Diseases in the United States. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2009. pp. 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Health I. Personal communication. 2008.

- 25.Kim WR, Benson JT, Hindman A, Brosgart C, Fortner-Burton C. Decline in the need for liver transplantation for end stage liver disease secondary to hepatitis B in the US. Hepatology. 2007;46(4 Suppl S):238A. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim WR, Poterucha JJ, Kremers WK, Ishitani MB, Dickson ER. Outcome of liver transplantation for hepatitis B in the United States. Liver Transplantation. 2004;10(8):968–74. doi: 10.1002/lt.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiesner RH, Freeman RB, Mulligan DC. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular cancer: the impact of the MELD allocation policy. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl 1):S261–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim WR, Ishitani MB, Dickson ER. Rising burden of hepatitis B in the United States: Should the ‘other’ virus be forgotten? Hepatology. 2002;36(4):222A. [Google Scholar]