Abstract

Social amoebae feed on bacteria in the soil, but they aggregate when starved and form a migrating slug that will undergo fruiting body morphogenesis to produce terminally differentiated spores and stalk cells. We describe a new cell type in the social amoeba which appears to provide detoxification and immune-like functions, which we term Sentinel (S) cells. S cells were observed to engulf bacteria and sequester toxins while circulating within the slug, eventually being sloughed off. A Toll/Interleukin-1 Receptor (TIR) domain protein, TirA, was also required for some S cell functions and for vegetative amoebae to feed on live bacteria. This apparent innate immune function in social amoebae, and the use of TirA for bacterial feeding, suggests an ancient cellular foraging mechanism that may have been adapted to defense functions well before the diversification of the animals.

Keywords: innate immunity, detoxification, phagocytosis, Dictyostelium, amoebozoa

Phagocytes that engulf bacteria, first described by Metchnikoff in 1883, form part of the animal innate immune system in the defense against pathogens (1–4). Both plants and animals also use innate signaling pathways as a means of sensing microbial pathogens; mainly through Toll-like receptors (TLRs) in animals and resistance (R) proteins in plants (5, 6). Both TLRs and R proteins bind to bacterial elicitors through leucine-rich repeats (LRRs) and signal through adaptor/effector proteins, such as those containing TIR domains (4, 6–8) and this, in turn, initiates the transcriptional programs that mediate specific defense responses (4, 9, 10).

The social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum lives in the soil and feeds on bacteria so it must defend against environmental toxins and pathogens. However, threats to Dictyostelium’s survival must also occur during its development, when amoebae aggregate to form a multicellular organism within a semi-permeable sheath and eventually produce a fruiting body with environmentally resistant spores held aloft by a cellular stalk (11). Prior to fruiting body formation the cells can migrate as a slug-like organism for several days. During this time exposure to toxins or bacterial pathogens have the potential of compromising survival by limiting spore production.

We sought to examine potential protective or detoxification pathways that might exist in the social amoeba. To visualize such pathways, we used fluorescent dyes as surrogates for the environmental toxins that Dictyostelium slugs might encounter in the soil (12). Five fluorescent dyes that we tested were all found to accumulate within a small subset of cells that were scattered throughout the slug (fig. S1)(13). Ethidium bromide (EB) displayed the highest differential accumulation within these cells (Fig. 1, A and B). The selective retention of EB suggests that these cells are a distinct population and the EB labeling allowed us to track the migration of these cells within the slug.

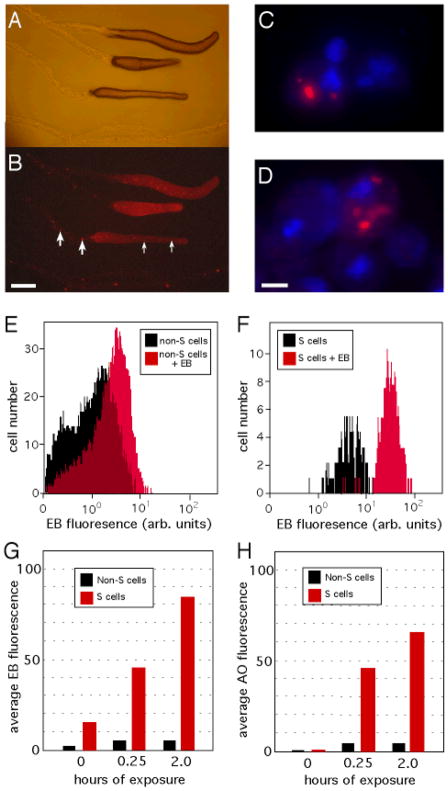

Fig. 1.

Accumulation of ethidium bromide (EB) by S cells. Bright field (A) and fluorescence (B) images of Dictyostelium slugs migrating, left to right, on agar containing 1 μg/ml EB reveals single cells (small arrows) and clumps of cells (large arrows) that are left behind within the sloughed off slug sheaths. (C) Fluorescent image of slug cells, with DAPI-stained nuclei (blue), showing two EB-negative cells and one cell containing EB within a large cytoplasmic vesicle (red). (D) Naïve slug cells suspended in 10 μg/ml EB for 15 min and visualized as in (C). Flow cytometry profiles of FACS-purified non-S cells (E) and S cells (F) before and after a 15-min exposure to 10 μg/ml EB. Quantification of the average cellular fluorescence of cells exposed to EB (G), or acridine orange (H), at 10 μg/ml. Scale bars, 250 μm (A and B), and 2 μm (C and D).

The cells appeared to circulate within the slug as single cells, moving laterally, forward and backward relative to the other cells. The cells also clumped together into immobile groups of 5–10 cells that were seen to attach to the inner surface of the slug sheath. These cell clumps were left behind in the discarded sheath as the slug continued to migrate, being deposited at regular intervals (Fig. 1A and B). Microscopic examination of disaggregated slugs revealed that the identified cells sequester EB within large vesicles (Fig. 1C) and that their numbers within slugs remained stable over time (~1% of slug cells). Since the cells were continuously sloughed off, this suggests that new cells arise continuously within the slug. The cells’ ability to sequester EB, along with their movement within, and exit from, the slug suggests that they mediate toxin removal, so we refer to them as Sentinel cells, or “S” cells.

When naïve slugs were disaggregated and exposed to EB, ~1% of the cells sequestered the dye in cytoplasmic vesicles within minutes and came to resemble S cells (Fig. 1D). The number and appearance of these cells did not change over several hours, suggesting that these were S cells present in the slug cell population prior to EB exposure. We next purified S cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) (fig. S2A) to test their ability to take up additional EB (12) and found that S cells could sequester at least tenfold more EB than non-S cells after 15 minutes of exposure (Fig. 1, E–G). Similar results were obtained when purified S cells were incubated with another dye, acridine orange (Fig. 2H). This demonstration of dye accumulation by S cells in dilute suspension suggests how S cells might aid in toxin removal from the slug, thus sparing prespore cells from genotoxic stress. EB-exposed S cells also displayed reduced viability, increased sensitivity to killing by UV light and a higher mutation frequency than other slug cells (fig. S2). S cells appeared to be present in five other species of Dictyostelia that we examined, as identified by the pattern of cellular EB accumulation within migrating slugs and slime trails (fig. S3), suggesting that they represent a general characteristic of the social amoeba (14).

Fig. 2.

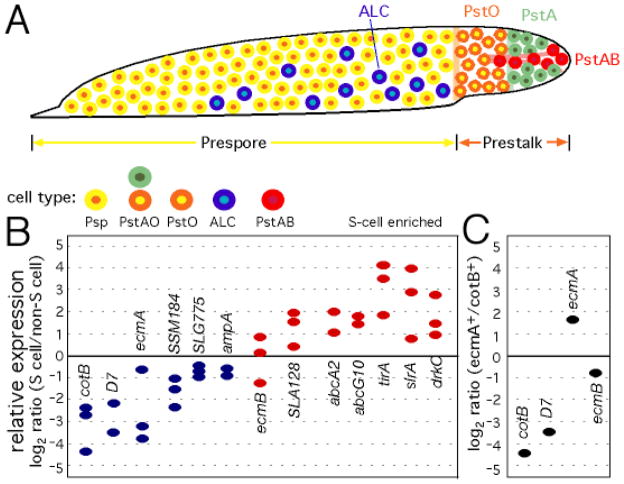

Gene expression profile of S cells. (A) Cartoon of a Dictyostelium slug (anterior to the right) with the major cell types indicated by colored circles (yellow, prespore; green, prestalk A; orange, prestalk O; red, prestalk AB; blue, anterior like cells). (B) qRT-PCR was used to compare gene expression in FACS-purified S cells relative to non-S cells (12). Blue ovals indicate relatively low expression in S cells, while red ovals indicate higher relative expression in S cells [prespore genes, cotB and D7; PstAO, ecmA; PstO, SSM184 and SLG775; ALC, ampA; PstAB, ecmB and SLA128]. (C) Positive control for the qRT-PCR, comparing gene expression in cotB/gfp-positive (prespore) and ecmA/gfp-positive (prestalk) cells.

To determine whether the S cells represent a distinct cell type, we purified them by FACS and estimated the level of specific mRNAs by quantitative, reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) (12). Genes were examined that distinguished the major cell types, represented in Fig. 2A (15–17). The expression of prespore, prestalk A and prestalk O genes was low in S cells (Fig 2B), consistent with the results obtained with cotB/GFP and ecmA/GFP reporter genes (fig. S4). There did appear to be enriched expression of prestalk AB genes in S cells, although S cells were not found to co-localize with prestalk AB cells. Thus, the distribution and gene expression profile of S cells was distinct from all defined cell types (15–18), suggesting that they represent a novel cell population.

Given the intriguing properties of S cells, we postulated that they represent a dedicated cellular defense system. A survey of the Dictyostelium genome (19) identified potential homologs of plant and animal innate immunity signaling proteins, including; a putative WRKY transcription factor (9); 16 potential LRR-domain receptors, including SlrA that is most similar to the rice protein Xa21 (20); and two proteins, TirA and TirB, with predicted TIR domains similar to those found in Arabidopsis RPP5 (21). Of these, we tested tirA and slrA by qRT-PCR and found that their mRNAs were eightfold enriched in S cells (Fig. 3D). Expression of the ABC transporter genes abcA2 and abcG10 (22) was also found to be enriched in S cells (Fig. 3D). For comparison, we purified ecmA/GFP-positive cells and detected a threefold enrichment of ecmA expression in these cells (Fig. 3E). Since ecmA expression has been shown to be specific to prestalk cells (23), this control indicates the limits of purifying minority cells types by FACS and suggests that tirA and slrA expression is indeed specific to S cells.

Fig. 3.

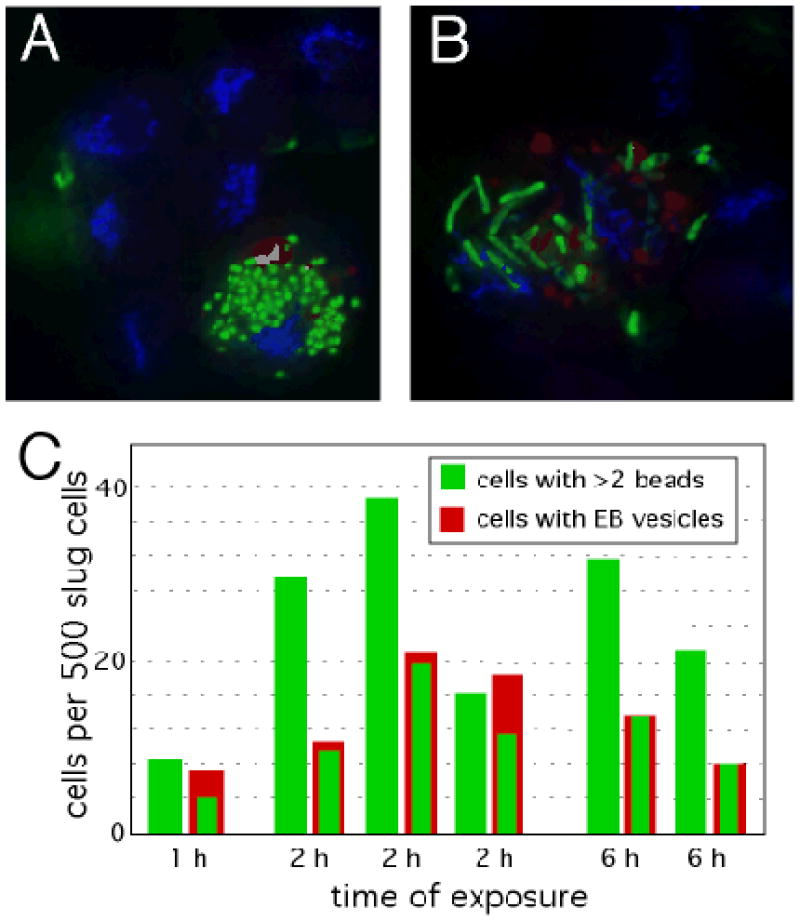

S cell phagocytosis. Slug cells were incubated with green fluorescent latex beads (A) or green fluorescent protein-labeled Legionella bacteria (B) for 1h, stained with DAPI (blue) and imaged by fluorescence microscopy (12). (C) The number of slug cells that engulfed beads were scored after the indicated times in separate experiments.

When slugs were disaggregated and mixed with fluorescent latex beads or bacteria, only the S cells were found to have an ability to engulf these efficiently (Fig. 4, A and B) (12). Quantification of particle uptake across the entire population of slug cells revealed that all S cells eventually take up a large number of beads (~50) (Fig. 4C). A similar number of cells that could not unequivocally be identified as S cells also engulfed the beads. The EB-negative phagocytes may represent a population of S cells that had not elaborated detectable EB-filled vesicles.

Fig. 4.

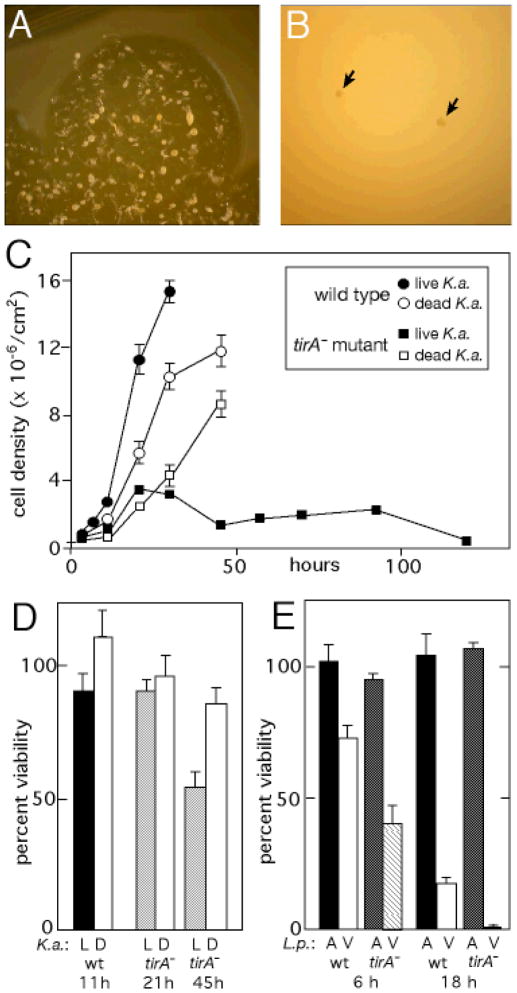

TirA requirement for growth on bacteria. (A) A 1-cm diameter colony of wild-type Dictyostelium on a lawn of Klebsiella aerogenes (K.a.) bacteria. The amoebae in the center have exhausted the bacteria and are undergoing multicellular development. (B) Two colonies of tirA mutant cells (arrows) plated at the same time as those in (A). (C) Wild-type and tirA mutant amoebae plated with live, or dead (heat-killed), K.a. bacteria. (D) The viability of cells was estimated at various times of growth in (C) on live (“L”) or dead (“D”) bacteria (12). (E) The tirA mutant cells show decreased survival after exposure to virulent (“V”) Legionella pneumophila (L.p.), at an MOI of 20, for 6 h and 18 h. Exposure to an avirulent (“A”) mutant L.p. (icmT) is shown for comparison.

The phagocytic nature of S cells suggested that they might play a role in the defense against pathogens. Legionella pneumophila is a bacterial pathogen of soil amoeba that escapes the phagosome maturation pathway normally used by amoebae to digest bacteria and eventually kills the host, or promotes its own exocytosis, allowing its dissemination to nearby cells (24–27). Since a Legionella infection within the slug could compromise spore production, it is possible that S cells help prevent or limit such damage. To examine this, we mixed disaggregated slug cells with Legionella, allowed them to re-form slugs, following the subsequent fate of the bacteria during continued slug migration (12). In these experiments, Legionella were swept into re-forming slugs by adhering to amoebae, or by being taken up into cells. Within 6 h, as the slugs migrated away from the site of mixing, the S cells were seen to contain numerous Legionella, and the majority of Legionella were found inside S cells (table S1). After 18h, infected cells or Legionella bacteria could not be detected within the slugs, though S cells were still present (table S1). Clumps of Legionella bacteria were observed within the collapsed sheaths that are left behind by the slugs, at intervals consistent with their being deposited there by S cells. The bacteria were not visible within cells, but appeared to be surrounded by cell debris. We also infected slugs directly by forcing several dozen Legionella bacteria through the slug sheath with a needle, without disrupting the integrity of the slug (12). After 6 h, all of the bacteria were found within a small number of cells in the slug, about half of which could be unambiguously identified as S cells (table S1). After 24 h of migration no bacteria could be detected within the slugs. Thus, S cells appear to locate and engulf pathogenic bacteria within the context of a migrating slug and show a capacity to clear them from the slug over time.

S cells’ ability to sequester pathogens and remove them from the slug “body” of the social amoeba is akin to neutrophil function in mammals. To explore this possible similarity further, we returned to the role of the tirA gene, since TIR-domain proteins regulate responses to pathogens in both plants and animals (6–8, 21, 28, 29). Partial deletion mutants were generated in which ~40% of the coding region, including the entire TIR domain, was replaced with a drug resistance cassette (fig. S5A–C). The tirA mutant slugs produced normal numbers of S cells on EB-agar and the cells themselves appeared grossly normal, with large cytoplasmic EB vesicles (fig. S5D). However, tirA mutant S cells were killed by an “avirulent” Legionella strain that does not kill wild-type Dictyostelium (fig. S5E). These results indicate that while TirA is not required for S cell differentiation, it is critical for the effective response of S cells to bacteria.

The tirA mutants were also observed to form minute colonies on bacterial lawns (Fig. 4A and B; fig. S5C). Since the tirA mutants grow normally in liquid media, this suggests a specific defect in their ability to feed on bacteria. We tested this by seeding cells on agar plates along with Klebsiella aerogenes (Dictyostelium‘s standard food bacteria) and found that the tirA mutant cells grew for ~20 hours, but then stopped growing and decreased in number thereafter (Fig. 4C). This growth defect was not due to the mutant’s inability to utilize bacteria as a food source because the mutant cells grew on heat-killed bacteria (Fig. 4C). The growth attenuation of the tirA mutant amoebae correlates with a discernable loss of cell viability (Fig. 4D). In addition, tirA mutant cells appeared to be more sensitive to killing by Legionella (Fig. 4E). Our results suggest that TirA is required by Dictyostelium amoebae to respond appropriately to bacteria during vegetative foraging.

We have described a new cell type in developing social amoebae, Sentinel (S) cells, which sequester toxins and bacterial pathogens and carry them away from the presumptive spore population. Given their functional parallels with neutrophils and macrophages, we suggest S cells provide a simple innate immune system for the social amoebae. We hypothesize that the S cells’ compromised fitness is advantageous because it increases the fitness of the prespore cells. This idea, along with the identification of what appear to be S cells in five other species of Dictyostelia, adds another layer of complexity to the cellular cooperation observed in the social amoeba (30).

Multicellularity likely increased the selective pressure on an organism’s ability to avoid exploitation by pathogens (1). Although plants and animals share a similar organization of innate immune signaling pathways, the hypothesized conservation of the component proteins has been called into question and proposed to have resulted from convergent evolution (5, 6, 31). Examining the response of amoebae to bacteria might clarify this issue since the amoebozoa diverged soon after the plant/animal split and form a basal group of the crown group eukaryotes (32–34). Moreover, amoebae are phagocytic cells that are in constant contact with bacteria and they might have retained key characteristics of plant and animal innate immunity if those functions existed in their common ancestor. The role of TirA in Dictyostelium’s response to bacteria provides the first glimpse of an immune-related signaling system in amoeba and suggests that the use of TIR domain-based signaling for defense represents an ancient function present in the progenitor of all crown group eukaryotes. If true, it would suggest that this system of pathogen recognition was advantageous to organisms prior to the evolution of multicellularity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Gad Shaulsky, Waleed Nasser, Joan Strassmann, David Queller and William F. Loomis for helpful discussions, Chenyu Zhang for advice on Legionella infections, Dorothy Lewis and Jeff Scott for flow cytometry advice, Howard Shuman for Legionella strains and Strassmann and Queller for additional species of Dictyostelia. This work was supported by grants GM52359 and HD39691 from National Institutes of Health to A.K..

Footnotes

Materials and Methods

References and Notes

- 1.Janeway CA, Jr, Medzhitov R. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tauber AI. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:897. doi: 10.1038/nrm1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Germain RN. Nat Med. 2004;10:1307. doi: 10.1038/nm1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Cell. 2006;124:783. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA., Jr Curr Opin Immunol. 1998;10:12. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nurnberger T, Brunner F, Kemmerling B, Piater L. Immunol Rev. 2004;198:249. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, et al. Nature. 2000;408:111. doi: 10.1038/35040600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burch-Smith TM, et al. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e68. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eulgem T. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:71. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen QH, et al. Science. 2007;315:1098. doi: 10.1126/science.1136372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kessin RH. Dictyostelium: evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science online.

- 13.Good JR, Kuspa A. Dev Biol. 2000;220:53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaap P, et al. Science. 2006;314:661. doi: 10.1126/science.1130670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams J. In: Dictyostelium - A model system for cell and developmental biology. Maeda Y, Inouye K, Takeuchi I, editors. Universal Academy Press; Tokyo, Japan: 1997. pp. 293–304. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casademunt E, Varney TR, Dolman J, Petty C, Blumberg DD. Differentiation. 2002;70:23. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda M, et al. Euk Cell. 2003;2:627. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.3.627-637.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sternfeld J, David CN. Differentiation. 1981;20:10. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eichinger L, et al. Nature. 2005;435:43. doi: 10.1038/nature03481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SW, Han SW, Bartley LE, Ronald PC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605508103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parker JE, et al. Plant Cell. 1997;9:879. doi: 10.1105/tpc.9.6.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anjard C, Loomis WF. Eukaryot Cell. 2002;1:643. doi: 10.1128/EC.1.4.643-652.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams JG. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:694. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horwitz MA. J Exp Med. 1983;158:2108. doi: 10.1084/jem.158.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shuman HA, Purcell M, Segal G, Hales L, Wiater LA. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1998;225:99. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80451-9_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon JM, Rupper A, Cardelli JA, Isberg RR. Inf Immun. 2000;68:2939. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2939-2947.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, et al. Science. 2004;303:1358. doi: 10.1126/science.1094226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slack JL, et al. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown V, Brown RA, Ozinsky A, Hesselberth JR, Fields S. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:742. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strassmann JE, Queller DC. ASM News. 2004;70:526. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ausubel FM. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:973. doi: 10.1038/ni1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baldauf SL, Doolittle WF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12007. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bapteste E, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032662799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song J, et al. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1:e71. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.