Abstract

A 47-year-old gentleman with a medical history of long-standing migraine presented with temporary total body paralysis and expressive aphasia for 4 h. It was also associated with worsening severe unilateral pulsating pain, nausea, photophobia, blurred vision, hearing disturbance and neck stiffness. All these symptoms were resolving gradually after 4 h and had resolved completely after 1 day. Investigations were unremarkable. Migraine was made as a diagnosis of exclusion.

Background

Migraine, a common and disabling disorder, is one of the most common complaints in medicine.1 2 It can be diagnosed using international headache society diagnostic criteria.3 Patients with migraine can have different clinical presentations. Therefore, the diagnosis of migraine can be rather straightforward or misleading. It is also important to note that migraine can be a diagnosis of exclusion. Here we report a patient who had an unusual presentation of migraine. The signs and symptoms he experienced do not quite fit into any types of migraine.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old gentleman with medical history of head injury 17 years ago and long standing migraine for 15 years presented with temporary total body paralysis and expressive aphasia for 4 h. The patient has been diagnosed with frontal migraine 15 years ago and occipital migraine 7 months ago. The usual frontal migraine does not affect his motor function and speech at all. The frontal migraine always starts in left eye which causes throbbing pain around the left eye, central bloody vision, blurred peripheral vision and photophobia. On the other hand, the occipital migraine always starts in the back of his left head and causes unilateral severe pulsating pain radiating from the back of the head to the left sided forehead. The occipital migraine is also associated with slurred speech and generalised limb weakness. He usually has 3–4 episodes of migraine each week with each episode lasting about 4–6 h. In this particular episode, the patient woke up at 7 a.m with moderate pulsating pain in left occipital region radiating to left frontal zone, photophobia, blurred vision, nausea and unsteadiness. The patient took sumatriptan 50 mg, propanolol 40 mg, nurofen 342 mg and paracetamol 500 mg before going to bed again. His condition had deteriorated profoundly when he woke up 3 h later. He was having severe left occipital pain radiating to left temporal and left frontal regions, total body paralysis, hearing disturbance and expressive aphasia. His wife called the ambulance after finding him staring at the ceiling and unresponsive. The patient’s condition had improved slightly after he was admitted to emergency department at around 12 p.m. He was just able to move his eyes, nod and wiggle his fingers and toes appropriately when instructed. He improved dramatically after 2 h at around 2 p.m. He was conscious in the whole event and had gradually gained back his normal motor function and speech. However, the whole event was like a dream to the patient as he could not be sure whether it was real or not. He still complained of joint stiffness, limb weakness, headache and blurred peripheral vision. Cranial nerve examination revealed no change in smell and taste, absence of ophthalmoplegia, equal pupillary reflex and accommodation, blurred peripheral vision, intact facial sensation, absence of facial palsy, normal hearing, intact swallowing and coughing reflex and intact hypoglossal nerve. Neurological examination showed no fasciculation of muscles, normal tone on both sides, decrease in upper and lower limbs motor power to 4/5, intact sensation on both sides, bilaterally equal reflexes, equal and intact sensation bilaterally, downgoing plantar reflexes, absence of ophthalmoplegia and nystagmus, normal speech, bilateral mild intentional tremor, past pointing on finger-nose test and heel-shin test, mild ataxia and no dysdiadochokinesia. The neurological examination indicated that the patient was having mild cerebellar signs bilaterally. One day after the episode, the patient had resolved spontaneously without any residual disability.

Investigations

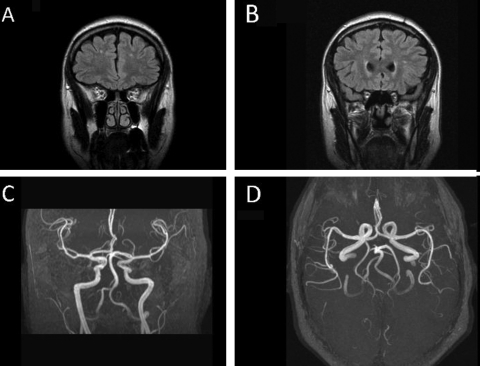

CT scan was done on admission which revealed no abnormalities. A number of MRI and EEG had also been done previously (figure 1). All investigations had been negative except for the most recent MRI in august 2011 which showed minor changes of periventricular white matter ischaemia. Other than that, midbrain, pons, brain stem and cerebellum were all normal. MRA in August 2011 showed no abnormalities as well. No MRI was done on admission (figure 1).

Figure 1.

(A and B) (Flare images of MRI of brain): the brain parenchyma shows normal appearance with normal distribution of grey and white matter. No intracranial haemorrhage or acute cortical infarcts. Minor changes of periventricular white matter ischaemia is seen as tiny foci of hyperintensities on flare images and within the peri-ventricular white matter. There were absence of midline shift, acute cortical infarcts, extra axial haemorrhage or collection and intracranial space occupying mass lesion. No abnormalities were found on mid brain, pons, brain stem and cerebellum. (C and D) (MRA of circle of willis): normal appearances of circle of willis, with its branches. No aneurysm or any vascular abnormalities are identified.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of this headache with temporary complete body paralysis and expressive aphasia includes severe migraine, dissociative (conversion) disorder, periodic paralysis, transient ischaemic attack, subarachnoid haemorrhage and space-occupying lesions.

Treatment

The patient was treated conservatively with his same current medication therapy: sumatriptan 50 mg, propanolol 40 mg, nurofen 342 mg and paracetamol 500 mg.

Outcome and follow-up

One day after the event, the patient had almost fully recovered. On examination, the 12 cranial nerves and neurological function were normal. He was discharged home and referred to his neurologist for further follow-up.

Discussion

There are different types of migraine, all share basic features and each person will have a specific clinical presentation. Diagnosis of migraine is based on typical clinical features and exclusion of other causes. Some typical signs and symptoms of migraine include unilateral throbbing and pulsating pain, nausea, vomiting and photophobia. The two most prevalent types of migraine are migraine with aura and migraine without aura. Other rare forms of migraine include hemiplegic, ophthalmoplegic, retinal and basilar migraines. In this case, the patient does not fall into any types of migraine described above. He has been having migraine for a long period of time. His generalised weakness caused by occipital migraine is usually eased by the medications. Besides, in view of the patient’s long standing history of migraine, the patient’s strong family history of migraine, the presence of typical clinical features of migraine and the exclusion of other causes, he most probably had an episode of atypical severe migraine. However, the clinical features presented by this patient are very similar to hemiplegic migraine. The pathophysiology of hemiplegic migraine is not well understood due to its rarity. Some studies have shown that there is diffuse cortical swelling and cortical hyperintensity of the cerebral hemisphere as a result of hyperperfusion in hemiplegic migraine. This mechanism can lead to hemiparesis or hemiplegia and can also be associated with aphasia, visual disturbance, hearing problems, headache and cerebellar signs. This patient has most of the hemiplegic migraine’s typical clinical features. Although there has been no previous reported case of temporary complete paralysis in migraine, there is a possibility that this patient’s severe migraine has led to hyperperfusion of both cerebral hemispheres as a result of generalised cerebral vasodilatation. A MRI scan should have been done on admission to look for any changes in cerebral hemispheres. Unfortunately, MRI scan was not done for this patient due to its unavailability. It is also important to note that another possibility of this unusual presentation could be due to a combination of severe migraine and dissociative (conversion) disorder. ‘The common theme shared by dissociative (or conversion) disorders is a partial or complete loss of the normal integration between memories of the past, awareness of identity and immediate sensations and control of bodily movements’.4 The term ‘conversion’ means that a stressful event or experience leads the patient to develop bodily symptoms as symbolic expressions of a long standing psychological conflict as demonstrated in this patient.5 This patient might have suffered from dissociative motor disorder as a result of long standing severe migraine. Chronic migraine has no doubt been affecting him emotionally, socially and physically. In dissociative motor disorder, there may be an inability to move whole or part of the body.4 6 Paralysis could also be partial, with slow and weak movement, or complete.4 It can last from hours to days. It could also be associated with psychological aphonia, akinesia, visual disturbance, hearing disturbance and ataxia.4 Therefore, a combination of severe migraine and dissociative motor disorder could explain the signs and symptoms the patient had in this particular migraine episode and previous episodes of occipital migraine which led to generalised limb weakness and slurred speech. A patient without previous diagnosis of migraine first presents with the same signs and symptoms as described in this case can be confusing and misleading. Therefore, this case report is crucial to make people aware of a new possible unusual presentation of migraine and other important differential diagnosis.

Learning points.

-

▶

Migraine can be a diagnosis of exclusion.

-

▶

This case could be a new unusual way of presentation of severe complicated migraine.

-

▶

Other rare but potentially life-threatening conditions should always be considered and excluded.

-

▶

Other important but rare differential diagnosis should always be considered.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Buse DC, Manack A, Serrano D, et al. Sociodemographic and comorbidity profiles of chronic migraine and episodic migraine sufferers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2010;81:428–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dafer RM. Migraine headache [internet]. Medscape 1994-2011 [updated 2011 May 10; cited 2011 Nov 28]. Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1142556-overview (25 December 2011).

- 3.Headache classification committee of the IHS Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia 1988;8:1–96 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World health organization The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. World health organization, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens L, Rodin I. Psychiatry: an Illustrated Colour Text. London: Churchill livingstone; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 6.American psychiatric association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth edition American psychiatric press Inc; 1994 [Google Scholar]