Abstract

Fish represent the group of vertebrates with the largest number of species and the largest geographic distribution; they are also used in different ways by modern civilizations. The goal of this study was to compile the current knowledge on the use of ichthyofauna in zootherapeutic practices in Brazil, including ecological and conservational commentary on the species recorded. We recorded a total of 85 species (44 fresh-water species and 41 salt-water species) used for medicinal purposes in Brazil. The three most commonly cited species were Hoplias malabaricus, Hippocampus reidi, and Electrophorus electricus. In terms of conservation status, 65% of species are in the “not evaluated” category, and 14% are in the “insufficient data” category. Three species are in the “vulnerable” category: Atlantoraja cyclophora, Balistes vetula, and Hippocampus erectus. Currently, we cannot avoid considering human pressure on the population dynamics of these species, which is an essential variable for the conservation of the species and the ecosystems in which they live and for the perpetuation of traditional medical practices.

1. Introduction

Nature offers various resources that people use to guarantee their survival [1] and to reproduce their ways of life and their practices. The use and management of these resources is intimately linked with the needs of various human populations. Among traditional populations, the use of plant and/or animal resources for medicinal purposes has been reported by various authors as an essential practice in traditional medical systems [2–13]. Natural resources have been used in traditional medical practices since ancient times, and their use is spreading in contemporary society [14]. One very old alternative therapy involves the use of animals and their derivatives in the production of zootherapeutic medications [15]. Zootherapy is an important alternative for cures in local populations; it can also be useful for the development of new drugs in modern medicine [4].

In Brazil, zootherapy appears well established; its broad biological diversity, along with its cultural complexity, drive production of zootherapeutic products [16]. In addition, the difficulty in accessing the main health system encountered by some populations increases the demand for traditional medicine [17].

Among the animal taxa used as medicinal resources, fish deserve special attention due to their strong representation in zootherapeutic surveys in Brazil [2, 7, 8, 12, 30, 42]. As a resource, fish are exploited in different ways by each culture [36]. Their medicinal applications include the use of both body parts and materials produced by the fish, along with live individuals [22].

Many of the animals used medicinally are found on the list of endangered species [7]; the risk of extinction is not only for the species but also for the benefits they offer. One of the benefits resulting from research in zootherapy is the discovery of new compounds that have pharmacological potential [21]. Given what has been stated above, this study aims to gather the current knowledge on ichthyofauna used in zootherapeutic practices in Brazil. By doing so, we expect to broaden the knowledge base through a compilation of species used to provide a first approximation of the wealth of these resources and their potential. Additionally, the study will evaluate whether the habitat of these species influences its versatility of use and if there are differences in the diversity of species cited for each body system.

The information compilation was based on bibliographic data. We considered bibliographic data from book chapters, in periodicals publications, and technical information available in online databases. We only considered a valid taxa the identified on species level, since the use of clades identified on the genus level, without its proper description, does not allow the technical-scientific accumulation of the taxon, which justifies this compilation with a fewer species number when compared to Costa-Neto and Alves [42] and R. R. N. Alves and H. N. Alves [13].

The database generated contains information on taxonomy, habitat, conservation status through the IUCN, the part of the animal used, therapeutic indications, and the Brazilian states where the species were cited. Species nomenclature, their habitats, and conservation status were confirmed and updated according to [43–45].

Though the locations sampled employed different methods and collection efforts, we counted the numbers of species used for zootherapeutic purposes by Brazilian region (state) and therapeutic indication. While it was not possible to perform a refined comparative analysis on the distribution of species use, this method allowed us to record the breadth of geographic distribution of the zootherapeutic indications and the study frequency by Brazilian regions and states.

We used the Index of Relative Importance (IR) [46] to measure the versatility of use of each species. This index takes into consideration the properties attributed and the body systems that are indicated for each species. This index varies from 0 to 2, with 2 indicating the most versatile species. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to evaluate whether the relative importance of a species was related to its habitat (i.e., salt water or fresh water) and its conservation status. We also compared habitats relative to species wealth for each body system using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. BioEstat v.5.0 software was used for analysis [47].

Therapeutic indications were categorized according to body systems from [48]: digestive, respiratory, gynecological/urinary, circulatory, nervous, sensory, motor, puerperal, cutaneous, scarring, poisoning, neoplasia, hematopoietic, nutrition, infectious/parasitic, lack of sexual desire, anti-abortive, and postpartum. Indications that could not be classified in these systems were grouped as “undefined pains/disorders.”

2. Ichthyofauna in Traditional Medical Practices in Brazil

The inventory of ichthyofauna used in Brazilian zootherapy produced a list of 85 species, of which 44 are predominantly fresh water and 41 are predominantly salt water fishes; 22 are cartilaginous fish (Figure 1). The most commonly listed fish were Hoplias malabaricus (Bloch, 1794) (N = 15), followed by Hippocampus reidi Ginsburg, 1933 (N = 13), and Electrophorus electricus (Linnaeus, 1766) (N = 10) (Table 1). These three species are highly important for zootherapy due to their documented use in various regions of Brazil [24–26, 31, 36].

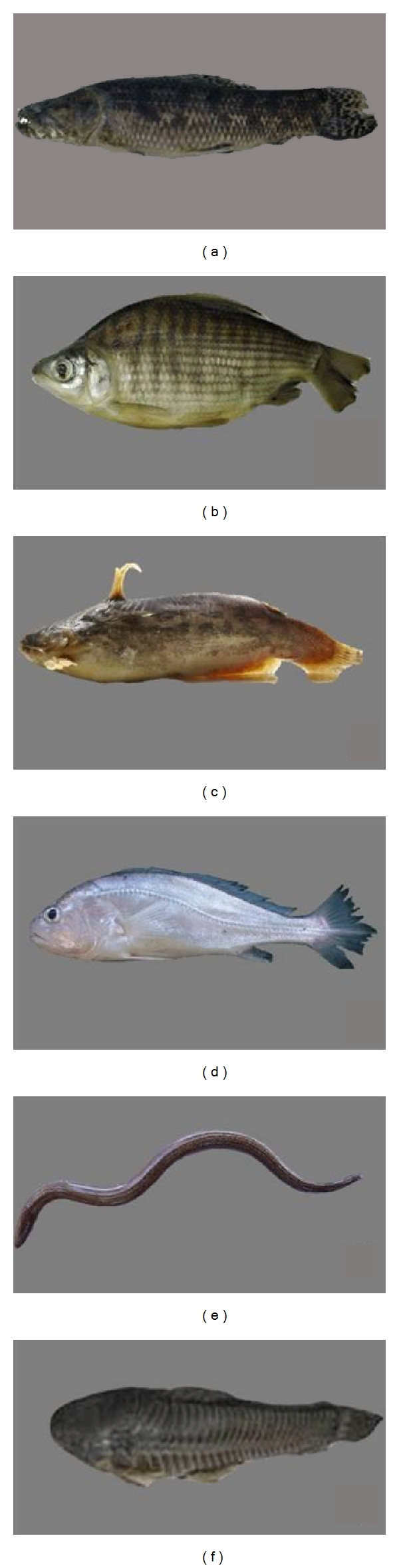

Figure 1.

Species cited in the traditional medicine of Brazil ((a) Hoplias malabaricus (Bloch 1794) (Trahira/Traíra), (b) Prochilodus argenteus Spix and Agassiz, 1829 (curimatã), (c) Trachelyopterus galeatus (Linnaeus, 1766) (Driftwood catfishes/Cumbá), (d) Plagioscion squamosissimus (Heckel, 1840) (South American silver croaker/Corvina), (e) Synbranchus marmoratus Bloch, 1795 (marbled swamp eel/muçum), (f) Callichthys callichthys (Linnaeus, 1758) (cascudo/caboje)).

Table 1.

Fish speciesused in traditional medicine in Brazil with local name, IUCN categories (EN: endangered, VU: vulnerable, LC: least concern, CR: critically endangered, NT: near threatened, NA: not available, DD: insufficient data), part used, therapeutic indication, number of bodily systems, state (occurrence), RI (relative importance), and reference.

| Taxa/local name | IUCN | Part used | Therapeutic indication | Number of bodily systems | State | RI | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predominantly salt water | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Chondrichthyes | |||||||

| Orectolobiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Ginglymostomatidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Ginglymostoma cirratum

(Bonnaterre, 1788) |

DD | Cartilage | Rheumatism | 1 | MA, PB | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Nurse shark/Cação-lixa) | |||||||

| Carcharhiniformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Carcharhinidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Carcharhinus limbatus

(Müller and Henle, 1839) |

NT | Cartilage, fat | Osteoporosis | 1 | MA | 0.138 | [7–9, 16] |

| (Blacktip shark/Sucuri-da-galha-preta) | |||||||

|

Carcharhinus porosus

(Ranzani, 1839) |

DD | Cartilage, fat | Asthma, rheumatism, wounds, inflammations, osteoporosis | 3 | MA, BA, PA | 0.492 | [7, 9] |

| (Smalltail/Cação-do-salgado) | |||||||

|

Carcharhinus leucas

(Muller and Henle, 1839) (Bull shark/Tubarão) |

NT | — | — | — | PE | — | [3] |

|

Galeocerdo cuvier

(Péron and Lesueur, 1822) |

NT | Cartilage, fat | Osteoporosis | 1 | MA, PI | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Tiger shark/Jaguará) | |||||||

|

Rhizoprionodon lalandii

(Müller and Henle, 1839) |

DD | Cartilage, fat | Rheumatism | 1 | PB, BA | 0.138 | [7, 9, 16] |

| (Sharpnose shark/cação-frango) Rhizoprionodon porosus (Poey, 1861) (Caribbean sharpnose shark/Cação de praia) |

LC | Cartilage, fat | Rheumatism | 1 | PB, BA | 0.138 | [7, 9, 16] |

|

| |||||||

| Sphyrnidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Sphyrna lewini

(Griffith and Smith, 1834) |

EN | Liver oil | Asthma, wounds, rheumatism | 3 | BA | 0.415 | [2] |

| (Scalloped hammerhead/Cação-martelo) | |||||||

| Pristiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Pristidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Pristis perotteti

Muller and Henlle 1842 |

CR | Rostral expansion | Rheumatism, arthritis | 1 | PA | 0.138 | [9] |

| (Sawfish/Espadarte) | |||||||

|

Pristis pectinata

(Latham, 1794) Smalltooth sawfish/espadarte |

CR | Rostral expansion | Asthma, rheumatism, arthritis | 2 | — | 0.135 | [18] |

| Rajiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Narcinidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Narcine Braziliensis

(Olfers, 1831) |

DD | Fat | Tooth pain | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2, 4] |

| (Brazilian electric ray/Raia elétrica) | |||||||

| Rajidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Atlantoraja cyclophora

(Regan, 1903) |

VU | Eggs | Postpartum hemorrhage | 1 | RJ | 0.138 | [19] |

| (Eyespot skate/Almofadinha/barata do mar) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Dasyatidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Dasyatis guttata

(Bloch and Schneider, 1801) |

DD | Teeth, liver oil, tail, ventral mucus, liver | Asthma, wounds caused by the fish itself, burns on the skin | 2 | PB | 0.315 | [7, 9] |

| (Longnose stingray/Raia branca) | |||||||

|

Dasyatis marianae

Gomes, Rosa, and Gadig, 2000 |

DD | Teeth, liver oil, tail, ventral mucus, liver | Asthma, wounds caused by the fish itself, burns on the skin | 2 | PB | 0.315 | [7, 9] |

| (Brazilian large-eyed stingray/raia mariquita) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Myliobatidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Aetobatus narinari

(Euphrasen, 1790) |

NT | Teeth, liver oil, tail, ventral mucus, liver | Asthma, wounds caused by the fish itself, burns on the skin, and hemorrhages | 3 | PA, PI, PB | 0.453 | [7, 9] |

| (Spotted eagle ray/raia-chita) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Urotrygonidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Urotrygon microphthalmum

(Delsman, 1941) |

LC | Teeth, liver oil, tail, ventral mucus, liver | Asthma, wounds caused by the fish itself, burns on the skin | 2 | PB | 0.315 | [7, 9] |

| (small-eyed, round stingray/raia) | |||||||

| Actinopterygii | |||||||

| Elopiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Megalopidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Megalops atlanticus

Valenciennes, 1847 |

NE | Scale | Asthma, lack of air, headache, stroke | 3 | MA, PB, AL | 0.454 | [7–9, 20] |

| (Tarpon/Camurupim/Cangurupim) | |||||||

| Anguilliformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Muraenidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Gymnothorax funebris

Ranzani, 1840 |

NE | Meat | Wounds | 1 | PB | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Green moray/moréia verde) | |||||||

| Gymnothorax moringa (Cuvier, 1829) | NE | Meat | Wounds | 1 | PB | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Spotted moray/moréia pintada) | |||||||

|

Gymnothorax vicinus

(Castelnau, 1855) (Purple mouth moray/moréia) |

NE | Meat | Wounds | 1 | PB | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

|

| |||||||

| Clupeiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Clupeidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Opisthonema oglinum

(Lesueur, 1818) (Atlantic thread herring/sardinha) |

NE | Entire | Alcoholism | 1 | PB | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| Siluriformes | |||||||

| Ariidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Bagre bagre

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

NE | Entire | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2, 21] |

| (Coco sea catfish/bagre-fidalgo) | |||||||

|

Genidens barbus

(Lacepède, 1803) |

NE | Entire | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2, 21] |

| (White sea catfish/bagre-do-mar) | |||||||

|

Genidens genidens

(Valenciennes, 1840) |

LC | Eye | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [22] |

| (Guri sea catfish/Bagre) | |||||||

|

Aspistor luniscutis

(Valenciennes, 1840) |

NE | Entire | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2, 21] |

| (bagre-urutu) | |||||||

| Gadiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gadidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Gadus morhua

Linnaeus, 1958 |

VU | Fat, skin | Rheumatism, furuncle, back pain | 2 | PB, BA | 0.315 | [2, 23] |

|

| |||||||

| (Atlantic Cod, bacalhau) | |||||||

| Batrachoidiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Batrachoididae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Thalassophryne nattereri

(Steindachner, 1876) |

NE | Meat, eye, and brain | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | MA, PI, BA | 0.138 | [2, 7, 9] |

| (niquim) | |||||||

| Lophiiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Ogcocephalidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Ogcocephalus vespertilio

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

NE | Entire | Asthma, bronchitis, rheumatism, arthritis | 2 | MA, PB, RJ | 0.354 | [7–9, 19] |

| (Seadevil/Peixe morcego) | |||||||

| Beryciformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Holocentridae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Holocentrus adscensionis

(Osbeck, 1765) |

NE | Sting | Wounds | 1 | RJ | 0.138 | [19] |

| (Squirrelfish/Jaguariçá) | |||||||

| Gasterosteiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Syngnathidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Hippocampus erectus

Perry, 1810 (Lined seahorse/Cavalo-marinho) |

VU | Entire | Alcoholism, thromboses, impotence, diabetes, osteoporosis, heart disease, bronchitis, cancer, asthma, and rheumatism | 6 | Brazil | 0.985 | [21] |

|

Hippocampus reidi

Ginsburg, 1933 (Longsnout seahorse/Cavalo-marinho) |

DD | Entire | Edema, asthma, bronchitis, impotence, thromboses, hemorrhage, hemorrhage in women, postpartum disorders, gastritis, tuberculosis, epilepsy, alcoholism, increasing female fertility, osteoporosis, heart disease cancer, asthma, rheumatism, avoiding miscarriage | 10 | RJ, PE, RN, PB, CE, BA, MA, PI, Brazil |

1.731 | [1, 2, 4, 7–9, 19, 24–29] |

| Perciformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Centropomidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Centropomus undecimalis

(Bloch, 1792) |

NE | Fat | Swollen legs, edema | 1 | BA | 0.177 | [2] |

| (Common snook/Robalo) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Sparidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Calamus penna

(Valenciennes, 1830) |

NE | Fin | Asthma | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2] |

| (Sheepshead porgy/peixe-pena) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Sciaenidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Cynoscion acoupa

(Lacepède 1802) |

LC | Otoliths | Renal insufficiency | 1 | MA | 0.138 | [8] |

| (Acoupa weakfish/Pescada amarela) | |||||||

|

Cynoscion leiarchus

(Curvier 1830) |

NE | Otoliths, Head | Renal insufficiency, lack of air | 1 | MA, PB | 0.177 | [8, 30] |

| (Smooth weakfish/Pescada branca) | |||||||

|

Micropogonias furnieri

(Desmarest, 1823) |

NE | Otoliths | Bronchitis | 1 | RJ | 0.138 | [29] |

|

| |||||||

| Trichiuridae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Trichiurus lepturus

(Linnaeus, 1758) (largehead hairtail/peixe espada) |

NE | Tail | Asthma | 1 | — | 0.138 | [18] |

| Tetraodontiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Balistidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Balistes vetula

Linnaeus, 1758 |

VU | Skin | Asthma, back pain | 2 | MA | 0.277 | [8] |

|

| |||||||

| (Queen-triggerfish/cangulo) | |||||||

|

Balistes capriscus

Gmelin, 1789 |

NE | Skin | Bronchitis | RJ | 0.138 | [29] | |

| (Grey-triggerfish/capucho) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Tetraodontidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Colomesus psittacus

(Bloch and Schneider, 1801) (Banded puffer/Baiacú) |

NE | Liver oil, bile | Breast cancer, back pain, warts | 3 | MA | 0.415 | [7, 9] |

|

| |||||||

|

Sphoeroides testudineus

(Linnaeus, 1758) (Checkered puffer/Baiacú) |

NE | Fat | Rheumatism | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [1] |

|

| |||||||

| Predominantly fresh water | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Chondrichthyes | |||||||

| Rajiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Potamotrygonidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Paratrygon ajereba

(Walbaum, 1792) |

DD | Spur, Fat | Asthma, cold, cough, ear pain, pneumonia, umbilical hernia, burns on the skin | 3 | TO | 0.569 | [31] |

| (Discus ray/raia) | |||||||

|

Plesiotrygon iwamae

(Rosa, Castello and Thorson, 1987) (Long-tailed river stingray/Arraia) |

DD | Fat | Wounds caused by the fish itself, cracks on the soles of feet, wounds | 1 | PA | 0.138 | [9] |

|

Potamotrygon hystrix

(Müller and Henle, 1841) (Porcupine river stingray/Raia) |

DD | Spur, Fat | Asthma, cold, cough, ear pain, pneumonia, umbilical hernia, burns on the skin | 3 | TO | 0.569 | [31] |

|

Potamotrygon motoro

(Müller and Henle, 1841) (South American freshwater stingray/Raia) |

DD | Spur, Fat | Asthma, cold, cough, ear pain, pneumonia, umbilical hernia, burns on the skin | 3 | TO | 0.569 | [31] |

|

Potamotrygon orbignyi

(Castelnau, 1855) |

LC | Fat | Wounds caused by the fish itself | 1 | PA | 0.138 | [9] |

| (Smooth back river stingray/Arraia) | |||||||

| Actinopterygii | |||||||

| Osteoglossiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Arapaimidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Arapaima gigas

(Cuvier, 1829) |

DD | scale | Asthma | 1 | PA | 0.138 | [8] |

| (Arapaima/arapaima, pirarucu) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Osteoglossidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Osteoglossum ferreirai

Kanazawa, 1966 (Black arawana/Aruanã) |

LC | scale | Dermatological problems | 1 | AM | 0.138 | [32] |

| (Arapaima/arapaima, pirarucu) | |||||||

| (Cruvina, Crumatá) | Fat, meat | ||||||

|

Prochilodus nigricans

Agassiz 1829 |

NE | Fat, gall, meat | Inflammations, cholesterol, burns on the skin, wounds, rheumatism, chilblains, malaria, whooping cough | 5 | CE, TO, Brazil | 0.808 | [27, 33, 34] |

| (Black prochilodus/Curimatã, Papa-terra) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Anostomidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Leporinus piau

Fowler, 1941 |

NE | Fat | Rheumatism | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [35] |

| (Piau) | |||||||

|

Leporinus steindachneri

Eigenmann 1907 (Piau) |

NE | Fat | Cholesterol | 1 | CE | 0.138 | [27] |

|

| |||||||

|

Schizodon knerii

(Steindachner, 1875) (Piau branco) |

NE | Fat | Edema, leukoma | 2 | AL | 0.277 | [20] |

|

| |||||||

| Characidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Brycon nattereri

Günther, 1864 |

NE | Meat | Flu | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [36] |

| (Matrinchã) | |||||||

|

Piaractus brachypomus

(Cuvier, 1818) |

NE | Fat | Scarring | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [37] |

| (Pirapatinga/Caranha) | |||||||

|

Serrasalmus brandtii

Lütken, 1875 |

NE | Tail, gall, fat | Impotency, jaundice, edema, inflammations |

3 | BA, AL | 0.454 | [20, 22, 35] |

| (White piranha/Piranha) | |||||||

|

Mylossoma duriventre

(Cuvier, 1818) (Pacu manteiga) |

NE | Fat | STDs | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [31] |

|

| |||||||

| Incertae sedis in Characidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Astyanax cf. bimaculatus

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

NE | Entire | Alcoholism | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [2] |

| (Two-spot astyanax/Piaba) | |||||||

|

Chalceus macrolepidotus

Cuvier, 1818 |

NE | Entire, eye | Asthma | 1 | AM | 0.138 | [11] |

| (Pink tailed chalceus/Araripirá) | |||||||

|

Paracheirodon axelrodi

(Schultz, 1956) |

NE | Entire | Asthma | 1 | AM | 0.138 | [11] |

| (Cardinal tetra/Cardinal) | |||||||

|

Salminus hilarii

Valenciennes, 1850 |

NE | Head | Memory | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [37] |

| (Dourado) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Cynodontidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Hydrolycus scomberoides

(Cuvier, 1819) (Payara/Cachorra) |

NE | Fat | Ear pain | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [31] |

|

| |||||||

| Erythrinidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Erythrinus erythrinus

(Bloch and Schneider, 1801) |

NE | Entire | Asthma | 1 | AL | 0.138 | [20] |

| (Matroê) | |||||||

|

Hoplias lacerdae

Miranda Ribeiro, 1908 (Trahira/Traírão) |

NE | Fat | Rheumatism, “vilide” | 2 | BA | 0.277 | [35] |

|

| |||||||

|

Hoplias malabaricus

(Bloch 1794) (Trahira/Traíra) |

NE | Fat, epidermal secretion, “bucho”, entire, head, scale, meat | Alcoholism, ear pain, inflammations, cholesterol, sore throat, umbilical cord inflammation, contusions, inflamed ear, hearing problems, ocular inflammation, urinary infection, deafness, asthma, muscle strain, erysipelas, wounds, hemorrhages, snakebite, conjunctivitis, edema, rheumatism, leukoma, stroke, asthma, diarrhea, vision problems | 10 | AC, BA, RN, PA, PB, MA, PE, AL, TO |

2.000 | [1, 2, 8, 9, 11, 16, 20, 22, 24, 27, 28, 30, 31, 33, 36, 38] |

| Siluriformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Cetopsidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Cetopsis candiru

Spix and Agassiz, 1829 |

NE | Meat | Whooping cough | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [37] |

| (Candiru) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Aspredinidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Aspredinichthys tibicen

(Valenciennes, 1840) |

NE | Barbels | Asthma | 1 | MA | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Tenbarbed banjo/viola) | |||||||

|

Aspredo aspredo

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

NE | Barbels | Asthma | 1 | MA | 0.138 | [7, 9] |

| (Banjo/viola) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Callichthyidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Callichthys callichthys

(Linnaeus, 1758) |

NE | Entire | Asthma, umbilical hernia, bronchitis, helping a child to walk earlier | 3 | BA, AL | 0.454 | [2, 20, 39] |

| (Cascudo/Caboje) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Pimelodidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Brachyplatystoma filamentosum

(Lichtenstein, 1819) (Kumakuma/Filhote) |

NE | Fin | Cough, alcoholism | 2 | TO | 0.277 | [37] |

|

Phractocephalus hemioliopterus

(Bloch and Schneider, 1801) (Redtail catfish/Pirarara) |

NE | Fat | Burns on the skin, rheumatism, cough, wounds, bronchitis, whooping cough, hoarseness, pneumonia, asthma, cold, umbilical hernia | 3 | AM, TO, Brazil | 0.723 | [11, 31, 34, 37] |

|

Pseudoplatystoma corruscans

(Spix and Agassiz, 1829) |

NE | Fat | Burns on the skin | 1 | BA | 0.138 | [36] |

| (Spotted sorubim/Surubim) | |||||||

|

Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum

(Linnaeus, 1766) (Barred sorubim/pintado) |

NE | Fat, gall | Scarring, whooping cough, body pain, muscular pains, bone pain, bronchitis, stroke | 5 | TO | 0.769 | [37] |

|

Sorubimichthys planiceps

(Spix and Agassiz, 1829) |

NE | Meat | Tuberculosis, leishmaniasis | 2 | TO | 0.277 | [31] |

| (Firewood catfish/Surubim-chicote) | |||||||

|

Zungaro zungaro

(Humboldt, 1821) (Gilded catfish/Jaú) |

NE | Fat, skin, meat | Bronchitis, asthma, burns on the skin, rheumatism, cold, ear pain, tooth pain, chilblains | 6 | TO | 0.908 | [31, 37] |

|

| |||||||

| Doradidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Lithodoras dorsalis

(Valenciennes, 1840) |

NE | Fat | Swelling | 1 | PA | 0.138 | [9] |

| (Rock-bacu/bacu) | |||||||

|

Oxydoras niger

(Valenciennes, 1821) (Ripsaw catfish/Abotoado) |

NE | Fat | Asthma, bronchitis, grippe, scarring, dry skin | 3 | TO | 0.492 | [37] |

|

| |||||||

| Auchenipteridae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Trachelyopterus galeatus

(Linnaeus, 1766) (Driftwood catfishes/Cumbá) |

NE | Entire, spur | Impotence, umbilical hernia, asthma | 3 | BA, AL | 0.415 | [20, 35, 40, 41] |

|

| |||||||

|

Megalodoras uranoscopus

(Eigenmann and Eigenmann, 1888) (cuiú-cuiú) |

NE | Fat | Rheumatism | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [31] |

|

Pterodoras granulosus

(Valenciennes, 1821) (Granulated catfish/cuiú-cuiú) |

NE | Fat | Rheumatism | 1 | TO | 0.138 | [31] |

| Gymnotiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Gymnotidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Electrophorus electricus

(Linnaeus 1756) (Electric eel/Peixe Elétrico, Poraquê) |

LC | Entire, fat, spin, and bone | Acne, alcoholism, asthma, itching, contusions, headache, back pain, muscular pains, wounds, swelling, spots on the skin, osteoporosis, snake bite, insect bite, pneumonia, cold, rheumatism, deafness, muscle strain, thrombosis, tuberculosis | 8 | RN, PE, DF, AC, PA, MA, PI, PB, TO, BA |

1.608 | [1, 7–9, 12, 17, 27, 28, 31, 37] |

| Synbranchiformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Synbranchidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Synbranchus marmoratus

Bloch, 1795 (Marbled swamp eel/muçum) |

NE | Entire | Making the child walk sooner, bronchitis, asthma, bronchitis, umbilical hernia | 3 | BA | 0.454 | [2, 39] |

| Perciformes | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Sciaenidae | |||||||

|

| |||||||

|

Pachyurus francisci

(Cuvier, 1830) (San Francisco croaker/Cruvina, curvina-de-bico) |

NE | Otoliths | Asthma, back pain, diuretic effect, renal insufficiency | 3 | BA | 0.454 | [36] |

|

Plagioscion squamosissimus

(Heckel, 1840) |

NE | Otoliths | Kidney stones, renal insufficiency, urinary infection, hemorrhages, snake bite | 3 | TO | 0.492 | [31, 37] |

| (South American silver croaker/Corvina) | |||||||

|

Plagioscion surinamensis

(Bleeker, 1873) |

NE | Otoliths | Urinary infection, hemorrhages, snakebite | 3 | TO | 0.41538 | [31] |

| (Pacora/Corvina) | |||||||

These most frequently used fish resources are part of the native fauna, demonstrating the importance of local fauna as a source for traditional remedies. According to R. Alves and H. Alves [13], the composition and availability of fauna are factors that directly affect the composition of the local zootherapeutic arsenal.

The dissemination of zootherapeutic knowledge is reflected in the population's contact with resources that, in principle, are not available locally. Some species that are restricted to the coast, such as the seahorse (Hippocampus reidi), are broadly disseminated throughout the interior of Brazil [24, 25, 27]. The use of this species was recorded for populations in the interior, such as the cities of Santa Cruz do Capibaribe-PE [24], Crato-CE [33], Queimadas-PB [25], and Caruaru-PE [26]. This situation may be explained by the existence of commercial routes for medicinal animals involving different cities in Brazil [49]. An exotic species such as the cod Gadus morhua Linnaeus, 1958, is available commercially in various states in Brazil for culinary purposes, but it is also used medicinally in states such as Paraíba and Bahia [2, 23].

Zootherapeutic practice involving ichthyofauna was recorded in 14 Brazilian states, representing the North, Northeast, Center-West, and Southeast regions. The state of Bahia (28 spp.) had the highest number of fishes used as traditional remedies, followed by the states of Tocantins (21 spp.), Paraíba (19 spp.), Maranhão (16 spp.), and Pará (9 spp.). This may not reflect the true situation regarding zootherapy in Brazil; the number is likely underestimated due to the concentration of studies in these regions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of richness of ichthyofauna used in traditional medicine in Brazil.

The Northeast region was the best represented, with research performed in eight states: Piauí, Maranhão, Ceará, Rio Grande do Norte, Paraíba, Pernambuco, Alagoas, and Bahia. This region has a significant presence of zootherapy in curing practices [7, 50]. Alves [12], while recording zootherapeutic practices in this region, did not perform studies in Ceará and Rio Grande do Norte; however, studies performed that same year [27, 33] and in the following year [28] demonstrated the medicinal use of animals in these two states. The North region was the second-most frequently represented, followed by the Southeast and Center-West regions, which accounted for 7% of the studies.

3. Therapeutic Indications for Ichthyofauna

Various therapeutic indications have been associated with ichthyofauna for medicinal use in Brazil, with 83 different diseases or illnesses recorded, particularly asthma, rheumatism, wounds, alcoholism, and bronchitis.

Hippocampus reidi and Hippocampus erectus stand out among the salt water species, with RI (relative importance) values of 1.73 and 0.98, respectively. The importance of these species is also evident from the number of studies that reported them in their inventories, especially in Northeast Brazil.

Hoplias malabaricus scored highest on diversity among the predominantly fresh water species, with an RI of 2.00, the highest score among all the species in the inventory. This species also stood out regarding the number of parts of the fish that can be used in traditional remedies. Electrophorus electricus received the second-highest RI score (1.60). It was also evident that these species have regional importance, due to the fact that they are cited in various studies conducted in Northern and Northeast Brazil. There was no significant difference between the species regarding habitat, according to the Kruskal-Wallis test (H = 1.213; P = 0.270).

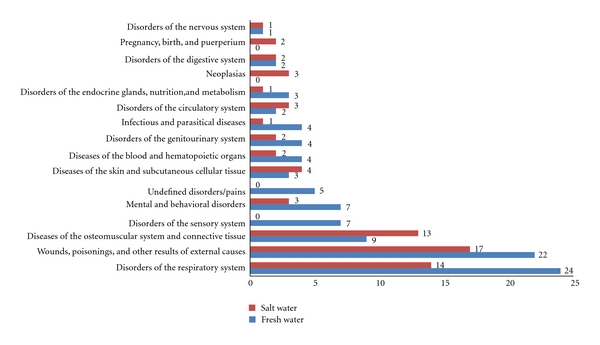

The therapeutic indications were grouped into 16 body systems (Figure 3). Of these, only two categories did not appear for the fresh water species: neoplasias and problems relating to pregnancy, birth, and puerperium. Two categories did not appear among salt water species: sensory system disorders and undefined pains/disorders.

Figure 3.

Body systems by fish species used in zootherapeutic practices in Brazil.

The systems with the greatest diversity of species included disorders of the respiratory system (e.g., asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia) and wounds, poisonings and other results from external causes (e.g., wounds caused by the fish itself, burns, and scarring). In spite of the fact that 57% of systems had greater diversity for fresh water than for salt water species, no significant differences in species wealth were observed (P = 0.374) between the two groups.

Often, a single species is the source of treatment for many diseases and infirmities [27]. Among the most versatile species are Hoplias malabaricus, Electrophorus electricus, Hippocampus reidi, Hippocampus erectus, and Phractocephalus hemiliopterus. The trahira (Hoplias malabaricus) was very versatile in treating 35% of therapeutic indications, ranging from bone and respiratory problems to alcoholism and snakebite. The electric eel (Electrophorus electricus) and the longsnout seahorse (Hippocampus reidi) treated 23% of indications each, and the redtail catfish (Phractocephalus hemiliopterus) and another species of seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) each treated 12%. It should be noted that seahorses and the trahira are heavily commercialized in Northeast Brazil [9, 51].

Although a particular species can be associated with various indications, these therapeutic uses may be associated with the use of different parts of the animal. The head of Hoplias malabaricus (trahira) is used for treatment of tetanus [38], while its scales are used to combat stroke [20], and the fat and skin secretion are indicated as a remedy for alcoholism [16, 27]. Another example of therapeutic versatility is found in Electrophorus electricus (electric eel), whose bones are used to treat snakebite [31], while the fat is associated with other indications, such as pains [26, 28, 31], rheumatism [7–9, 17, 26, 27, 31, 37], colds [31], asthma [31, 37], and pneumonia [8, 37].

Among the fish parts most commonly employed for the production of zootherapeutic products, fat stood out with a 40% use occurrence. Fish fat is indicated for various infirmities and diseases. Its use recurs often in popular medicine [31]; fat has been documented as the most commonly used animal part in various studies [8, 35]. In India, the fat from various animals is indicated for combating all types of pain, impotence, burns, and paralysis [52]. The widespread use of fat can be related to the ease of its extraction. Additionally, it can be preserved at room temperature for long periods [29].

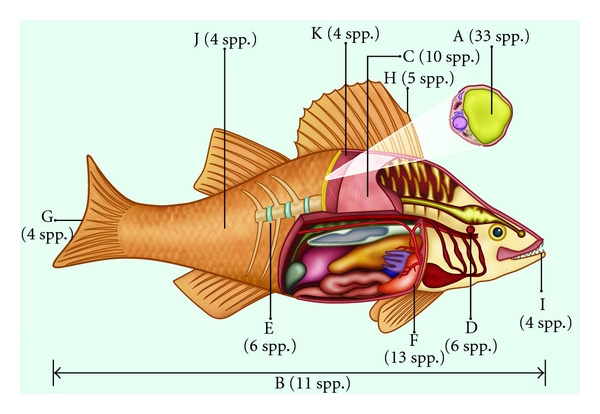

The use of various other parts of fish has also been recorded, including teeth, eyes, gall, liver, wattles, otoliths, fins, and stingers. Many fish parts used in zootherapy are not used for other purposes, such as scales and leathers, to maximize the use of local resources [35]. Another method for keeping therapeutic resources available are food taboos, through which the consumption of some of these species would lead to negative consequences, thereby keeping these animals available in case of necessity (Figure 4) [31].

Figure 4.

Richness of species according to the main body parts of fish used for therapeutic purposes in Brazil. (A: fat, B: entire, C: meat, D: otoliths, E: cartilage, F: liver, G: tail, H: spur, I: tooth, J: scale, K: skin).

In addition to dead animals and their parts, the use of living animals is a recurring practice in traditional medicine systems and is a part of the beliefs and “spells” in local systems [22]. A mystical use has been reported for the species Synbranchus marmoratus (marbled swamp eel) and Callichthys callichthys (armored catfish) [39] in the treatment of asthma; namely, one should spit in the mouth of a living animal, and then put it back in the river.

Another demonstration of aspects associated with popular medicine occurs when the morphology exhibited by the animal inspires its therapeutic application. Sometimes the morphology of the animal and/or the organs utilized is associated with the part of the human body to be treated because the similarities are interpreted as indicative of a potential benefit [35]. Moura and Marques [35] recorded the use of the common wood catfish (Trachelyopterus galeatus) in the treatment of impotence, due to the species' large, fringed testicles.

Zootherapy has been the focus of increasing attention from the pharmaceutical industry [7]. These industries have used the biologically active components present in traditional medicines as sources for the production of many drugs [53]. Compounds extracted from fish are already used in official medicine, such as Tetrodotoxin, which originates from pufferfish and possesses a powerful anesthetic effect [54–56]. Other widely distributed compounds from fish, omega-3 fatty acids, are associated with the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases, arthritis, kidney disease, and inflammation [57].

The exploitation of medicinal fauna resources by local populations and the pharmaceutical industry has had a negative impact on several species, with their survival threatened by overexploitation [10, 58]. Among the fish used therapeutically in Brazil, three species can be singled out as having an elevated danger of extinction and are included in the “vulnerable” category by the IUCN [59]: Atlantoraja cyclophora, Balistes vetula, and Hippocampus erectus. Sphyrna lewini is in the “in danger” category, with a very high risk of extinction, and Pristis perotetti and Pristis pectinata are “in critical danger.” Among these species are four cartilaginous fishes that have low levels of fecundity, such as the ray, the hammerhead shark, and the swordfish. Seahorses (Hippocampus spp.) are considered susceptible to exploitation and are threatened worldwide due to excessive use and destruction of habitat due to their high monetary value and potential for commercialization [51] (Figure 5). The species H. reidi, currently listed in the “insufficient data” category, is widely commercialized for medicinal purposes throughout Brazil and exhibits low reproduction and high mortality rates in initial phases [60].

Figure 5.

Box in the Market of São José (Recife, Brazil) with seahorse to sell.

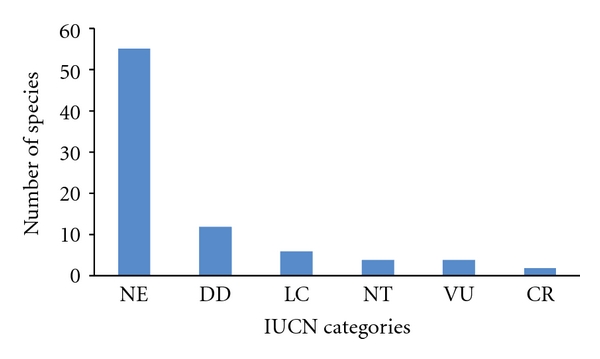

However, the great majority of fish identified in this survey have not yet been evaluated by the IUCN, or there is insufficient data for analysis (Figure 6). This fact highlights the scarcity of knowledge regarding the true situation of these fish, demonstrating the need for studies directed toward those species that are used medicinally to preserve these resources and all aspects linked to them. Also, there is no significant differences in the relative importance (RI) between IUCN categories according to the Kruskall-Wallis test (P > 0.05).

Figure 6.

IUCN categories of fish species used for medicinal purposes in Brazil (EN: endangered, VU: vulnerable, LC: least concern, CR: critically endangered, NT: near threatened, NA: not available, DD: insufficient data).

In addition, the extinction of some species could compromise both traditional knowledge and the discovery of new drugs [61] because these species could disappear before science becomes aware of their potential. The growing demand for the biotic resources used in traditional medicine is due to the increasing quantity of studies that demonstrate the efficacy of their use, drawing the attention of the pharmaceutical industry [62].

Extractivism is generally the only method for obtaining zootherapeutic resources, highlighting the need to add these species to conservation efforts by including creatures involved in zootherapeutic practices in planning for the management of fauna. Both the local population and the pharmaceutical industries can contribute in different ways to the maintenance of these resources. In addition, it is also necessary to understand the ecology and biology of the species used in medicine to propose effective strategies for managing these resources.

Final Considerations

We highlight the importance of fish in zootherapeutic practices in Brazil, emphasizing the knowledge gap that must be explored in ethnobiological and pharmacological research in the country. The Northeast region represents the major center for research on this subject, both in terms of the large number of publications and the number of local researchers.

We recommend greater investment in exploration projects for fish, especially in inland water resources, associating ecological parameters that drive population dynamics to better understand the relationships of humans with these resources. This will enable more efficient management proposals for the conservation of these species and their associated ecosystems and will allow for the perpetuation of traditional medical practices.

Acknowledgments

This paper is the contribution P002 of the Rede de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Saberes Locais (REBISA-Network of Research in Biodiversity and Local Knowledge), with financial support from FACEPE (Foundation for Science and Technology) to the project Núcleo de Pesquisa em Ecologia, Conservação e Potencial de Uso de Recursos Biológicos no Semiárido do Nordeste do Brazil (Center for Research in Ecology, Conservation and Potential Use of Biological Resources in the semiarid region of Northeastern Brazil: APQ-1264-2.05/10).

References

- 1.Costa-Neto EM. Traditional use and sale of animals as medicines in Feira de Santana City, Bahia, Brazil. Indigenous Knowledge and Development Monitor. 1999;7:6–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa-Neto EM, Marques GW. Faunistic resources used as medicines by artisanal fishermen from siribinha beach, state of Bahia, Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology. 2000;20(1):93–109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fátima C, Almeida CBR, Albuquerque UP. Uso e conservação de plantas e animais medicevais no Estado de Prnambuco (Nordeste do Brasil): um estudo de caso. Interciencia. 2002;27(6):276–285. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costa-Neto EM. Implications and applications of folk zootherapy in the state of Bahia, Northeastern Brazil. Sustainable Development. 2004;12(3):161–174. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silva ACO, Albuquerque UP. Woody medicinal plants of the caatinga in the state of Pernambuco (Northeast Brazil) Acta Botanica Brasílica. 2006;19:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Albuquerque UP, Hanazaki N. As pesquisas etnodirigidas na descoberta de novos fármacos de interesse médico e farmacêutico: fragilidades e pespectivas. Brazilian Journal of Pharmacognosy. 2006;16:678–689. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. From cnidarians to mammals: the use of animals as remedies in fishing communities in NE Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2006;107(2):259–276. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Zootherapy goes to town: the use of animal-based remedies in urban areas of NE and N Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;113(3):541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Zootherapeutic practices among fishing communities in North and Northeast Brazil: a comparison. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2007;111(1):82–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alves RRN, Rosa IML. Biodiversity, traditional medicine and public health: where do they meet? Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2007;3, article 14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva AL. Animais medicinais: conhecimento e uso entre as populações ribeirinhas do rio Negro, Amazonas. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas. 2008;3(3):343–357. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alves RRN. Fauna used in popular medicine in Northeast Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2009;5, article 1:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alves RRN, Alves HN. The faunal drugstore: animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2011;7, article 9:1–43. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lev E. Traditional healing with animals (zootherapy): medieval to present-day Levantine practice. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2003;85(1):107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(02)00377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Why study the use of animal products in traditional medicines? Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2005;1, article 5 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costa-Neto EM. A zooterapia popular no Estado da Bahia: registro de novas espécies animais utilizadas como recursos medicinais. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva. 2011;16(supplement 1):1639–1650. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232011000700100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costa-Neto EM, Motta PC. Animal species traded as ethnomedicinal resources in the federal district, central west region of Brazil. The Open Complementary Medicine Journal. 2010;2:24–30. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alves RRN, Rosa IL, Santana GG. The role of animal-derived remedies as complementary medicine in Brazil. BioScience. 2007;57(11):949–955. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Begossi A. Food taboos at Buzios Island (Brazil): their significance and relation to folk medicine. Journal of Ethnobiology. 1992;12(1):117–139. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marques JGW. Pescando Pescadores: Etnoecologia Abrangente no Baixo São Francisco Alagoano. São Paulo, Brazil: NUPAUB, Universidade de São Paulo; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costa-Neto EM. Animal-based medicines: biological prospection and the sustainable use of zootherapeutic resources. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciencias. 2005;77(1):33–43. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652005000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andrade JN, Costa-Neto EM. Primeiro registro da utilização medicinal de recursos pesqueiros na cidade de São Félix, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Scientiarum: Biological Sciences. 2005;27(2):177–183. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alves RRN, Barbosa JAA, Santos SLDX, Souto WMS, Barboza RRD. Animal-based remedies as complementary medicines in the semi-arid region of northeastern Brazil. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:15 pages. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nep134. Article ID 179876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alves RRN, Lima HN, Tavares MC, Souto WMS, Barboza RRD, Vasconcellos A. Animal-based remedies as complementary medicines in Santa Cruz do Capibaribe, Brazil. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2008;8, article 44:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barbosa JAA, Alves RRN. “Um chá de que?”. Animais utilizados no preparo tradicional de bebidas medicinais no agreste paraibano. BioFar: Revista Brasileira de Biologia e Farmácia. 2010;4(2):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alves RRN, Léo Neto NA, Brooks SE, Albuquerque UP. Commercialization of animal-derived remedies as complementary medicine in the semi-arid region of Northeastern Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2009;124(3):600–608. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira FS, Brito AV, Ribeiro SC, Saraiva AAF, Almeida WO, Alves RRN. Animal-based folk remedies sold in public markets in Crato and Juazeiro do Norte, Ceará, Brazil. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2009;9, article 17:1–18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-9-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oliveira ES, Torres DF, Brooks SE, Alves RRN. The medicinal animal markets in the metropolitan region of Natal City, northeastern Brazil. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2010;130(1):54–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Selxas CS, Begossi A. Ethnozoology of fishing communities from Ilha Grande (Atlantic Forest Coast, Brazil) Journal of Ethnobiology. 2001;21(1):107–135. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silva NLG, Ferreira SF, Coutinho HDM, Alves RRN. Zooterápicos utilizados em comunidades rurais do município de Sumé, Paraíba, Nordeste do Brasil. In: Costa-Neto EM, Alves RRN, editors. Zooterapia: Os Animais na Medicina Popular Brasileira. 1st edition. Vol. 1. Recife, Brazil: NUPEEA; 2010. pp. 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Begossi A, Braga FMS. Food taboos and folk medicine among fishermen from the Tocantins River (Brazil) Amazoniana. 1992;12(1):101–118. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodrigues E. Plants and animals utilized as medicines in the Jaú National Park (JNP), Brazilian Amazon. Phytotherapy Research. 2006;20(5):378–391. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferreira FS, Brito SV, Ribeiro SC, Almeida WO, Alves RRN. Zootherapeutics utilized by residents of the community Poço Dantas, Crato-CE, Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2009;5, article 21 doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Begossi A, Hanazaki N, Peroni N. Knowledge and use of biodiversity in Brazilian hot spots. Environment, Development and Sustainability. 2000;2(3-4):177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moura FDBP, Marques JGW. Zooterapia popular na Chapada Diamantina: uma medicina incidental? Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2008;13(2):2179–2188. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232008000900023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Costa-Neto EM, Dias CV, De Melo MN. O conhecimento ictiológico tradicional dos pescadores da cidade de Barra, região do médio São Francisco, Estado da Bahia, Brasil. Acta Scientiarum: Biological Sciences. 2002;24(2):561–572. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rocha MF, Poleto SL. Etnoictiologia de pescadores profissionais artesanais dos rios Araguaia e Garças nos municípios de Barra do Garças, MT, Pontal do Araguaia e Aragarças. Revista Interdisciplinar. 2009;1(2):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Begossi A, Silvano RAM, Do Amaral BD, Oyakawa OT. Uses of fish and game by inhabitants of an extractive reserve (Upper Juruá, Acre, Brazil) Environment, Development and Sustainability. 1999;1(1):73–93. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Costa-Neto EM. A Cultura Pesqueira do Litoral Norte da Bahia: Etnoictiologia, Desenvolvimento e Sustentabilidade. Bahia, Brazil: EDUFBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Costa-Neto EM. Conhecimento e usos tradicionais de recursos faunísticos por uma comunidade Afro-Brasileira. Resultados preliminaires. Interciencia. 2000;25(9):423–431. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Costa-Neto EM. Faunistic resources used as medicines by an Afro-brazilian community from Chapada Diamantina National Park, State of Bahia. Brazil. Sitientibus. 1996;(15):211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Costa-Neto EM, Alves RRN. Estado da arte zooterapia popular no Brasil. In: Costa-Neto EM, Alves RRN, editors. Zooterapia: Os Animais na Medicina Popular Brasileira. 1st edition. Vol. 1. Recife, Brazil: NUPEEA; 2010. pp. 15–54. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Froese R, Pauly D. FishBase. World Wide Web electronic publication. version (06/2011), http://www.fishbase.org/

- 44.Buckup AP, Menezes AN, Ghazzi MS. Catálogo das Espécies de Peixes de Água Doce do Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: Museu Nacional; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menezes NA, Buckup PA, Figueiredo JL, Moura RL. Catálogo das Espécies de Peixes Marinhos do Brasil. São Paulo, Brazil: Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bennett BC, Prance GT. Introduced plants in the indigenous pharmacopoeia of northern South America. Economic Botany. 2000;54(1):90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ayres M, Ayres M, Jr., Ayres DL, Santos AS. BioEstat 5.0—Aplicações estatísticas nas áreas das ciências bio-médicas. Pará, Brazil: Universidade Federal do Pará; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.World Health Organization (WHO) International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision, 2006.

- 49.Alves RRN, Rosa IL. Trade of animals used in Brazilian traditional medicine: trends and implications for conservation. Human Ecology. 2010;38(5):691–704. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silva MLV, Alves AGC, Almeida AV. A zooterapia no Recife (Pernambuco): uma articulação entre as práticas e a história. Biotemas. 2004;17:95–116. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosa IL, Oliveira TPR, Osório FM, et al. Fisheries and trade of seahorses in Brazil: historical perspective, current trends, and future directions. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2011;20(9):1951–1971. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Padmanabham P, Sujana KA. Animal products in traditional medicine from Attappady Hills of Western Ghats. Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge. 2008;7:326–329. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Costa-Neto EM, Oliveira MVM. Cockroach is good for asthma: zootherapeutic practices in Northeastern Brazil. Human Ecology Review. 2000;7(2):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hagen NA, du Souich P, Lapointe B, et al. Tetrodotoxin for moderate to severe cancer pain: a randomized, double blind, parallel design multicenter study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2008;35(4):420–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marcil J, Walczak JS, Guindon J, Ngoc AH, Lu S, Beaulieu P. Antinociceptive effects of tetrodotoxin (TTX) in rodents. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2006;96(6):761–768. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Padera RF, Tse JY, Bellas E, Kohane DS. Tetrodotoxin for prolonged local anesthesia with minimal myotoxicity. Muscle and Nerve. 2006;34(6):747–753. doi: 10.1002/mus.20618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Alexander JW. Immunonutrition: the role of ω-3 fatty acids. Nutrition. 1998;14(7-8):627–633. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kang S, Phipps M. A Question of Attitude: South Korea’s Traditional Medicine Practitioners and Wildlife Conservation. Hong Kong: Traffic East Asia; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.IUCN. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. version 2011.1, http://www.iucnredlist.org/

- 60.Rosa IML, Alves RRN, Bonifácio KM, et al. Fishers' knowledge and seahorse conservation in Brazil. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine. 2005;1, article 12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shanley P, Luz L. The impacts of forest degradation on medicinal plant use and implications for health care in eastern Amazonia. BioScience. 2003;53(6):573–584. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Montanari I., Jr. Aspectos da produção comercial de plantas medicinais nativas. CPQBA-UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil, 2002, http://www.cpqba.unicamp.br/plmed/artigos/producao.htm.