Abstract

The miniaturization of electrochemical sensors allows for the minimally invasive and cost effective examination of cellular responses at a high efficacy rate. In this work, an ink-jet printed superoxide dismutase electrode was designed, characterized, and utilized as a novel microfluidic device to examine the metabolic response of a 2D layer of macrophage cells. Since superoxide production is one of the first indicators of oxidative burst, macrophage cells were exposed within the microfluidic device to phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), a known promoter of oxidative burst, and the production of superoxide was measured. A 46 ± 19% increase in current was measured over a 30 min time period demonstrating successful detection of sustained macrophage oxidative burst, which corresponds to an increase in the superoxide production rate by 9 ± 3 attomoles/cell/sec. Linear sweep voltammetry was utilized to show the selectivity of this sensor for superoxide over hydrogen peroxide. This novel controllable microfluidic system can be used to study the impact of multiple effectors from a large number of bacteria or other invaders along a 2D layer of macrophages, providing an in vitro platform for improved electrochemical studies of metabolic responses.

Keywords: Microfluidic, Electrochemistry, Superoxide Dismutase, Ink-jet printing, Oxidative Burst

1. Introduction

Macrophages undergo oxidative burst as an immunological defense mechanism to eradicate foreign particles or bacteria. Understanding of this mechanism requires increased sensitivity, selectivity, and time resolution available through the combination of microfluidic technology with multianalyte detection. (Amatore et al. 2010; Chun 2009; Sia and Whitesides 2003) Traditional fabrication of microfluidic devices employs photolithography on glass, quartz, or silicon, but polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) can be used as a low-cost alternative.(Berdichevsky et al. 2004) As an optically transparent, chemically inert material, PDMS can be fabricated rapidly, making it ideal for biological applications,(Bodas and Khan-Malek 2006; Chikkaveeraiah et al. 2009) and provides a sterile, aqueous environment to trap cells and electrochemically detect analytes.(Ges and Baudenbacher 2010; Inoue et al. 2010) In this work, a novel microfluidic sensor has been developed to electrochemically monitor the metabolic changes of growing and infected macrophages in real-time.

Macrophages are white blood cells that degrade bacterium and other foreign pathogens. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by alveolar macrophages assist in the elimination of foreign particles which enter the body through the lungs.(Pieters 2008) Basal production of ROS by NADPH oxidase in the macrophage is low but becomes elevated to degrade pathogens via oxidative burst.(Costa Rosa et al. 1995; Grune and Davies 2003; Uchida 2003) Deviations from normal levels of ROS can lead to macrophage damage, cell death, or the impairment of cell proliferation and host responses. (Dietert and Golemboski 1998; Finkel and Holbrook 2000) Some bacteria, such as tuberculosis through lipoarabinomannan, have developed means through which they evade this mechanism of macrophage defenses. (Majumder et al. 2008) This study develops a system that can be used to quantify the production of superoxide upon exposure to lipoarabinomannan or other bacterial invaders as well as determine drug efficacy or effector pathways. Dynamic quantitative assay of ROS production would further the understanding of the immunological consequences of macrophage exposure to tuberculosis.

Reactive oxygen species are unstable due to their dismutation in a protic environment, making them difficult to analyze.(Endo et al. 2002; Radi 2004) For this reason, oxidative burst is traditionally detected in vitro spectroscopically or electrochemically by measuring hydrogen peroxide, the hydroxyl radical, or reactive nitrogen species (RNS, i.e., peroxynitrite, nitrite ions) production; these species are the more stable downstream products of superoxide (O2−) and nitric oxide radicals. The basal level of O2− is approximately 0.1 nM; enzymes keep this concentration at a steady state.(Imlay 2008) Any increase in this cellular concentration of O2− can have detrimental effects on a cell.(Di et al. 2007) Several means of O2− dismutation are present in vivo to prevent cellular damage, including the dismutation of O2− with water (105 M−1 s−1) and with superoxide dismutase (SOD, ~2×109 M−1 s−1).(Endo et al. 2002; Imlay 2008; Radi 2004; Sawyer and Valentine 1981) Since hydrogen peroxide is more stable than O2−, it is present at higher concentrations in culture,(Amatore et al. 2008b; Imlay 2008) and new detection methods are necessary to differentiate between each reaction product.(Dahlgren and Karlsson 1999) Measuring O2−, instead of one of its byproducts, will differentiate oxidative burst from other pathways that also generate hydrogen peroxide.

Previous work was performed to improve the detection of ROS and RNS from single cells using amperometry of H2O2, ONOO−, NO• and NO2− at varying potentials.(Amatore et al. 2006; Amatore et al. 2007; Amatore et al. 2008a; Amatore et al. 2010) While these results provided valuable information on the amperometric response of individual stimulated macrophage cells, they highlight the need to compare these individual numbers to the average of many cells in a more comprehensive analysis under immunological conditions. For this reason, we designed a microfluidic sensor to run experiments on a 2D layer of cells to determine meaningful statistical relationships among cellular responses and controls.

In developing our sensor, we incorporated both hand cast and ink-jet deposition to immobilize SOD, with one of the fastest reaction rates known in nature, for an O2− sensor. Many enzyme deposition techniques exist, but the challenge remains allowing the most direct electron transfer without destroying enzyme functionality.(Devadoss and Burgess 2002; Sokic-Lazic and Minteer 2008) There is a growing interest in ink-jet printing (IJP) due to its reproducibility in rapid, small-scale fabrication.(Deravi et al. 2007; Deravi et al. 2008; Di Risio and Yan 2007) This study compares hand-casting with printing of the SOD enzyme film. The impact of the printing process on the enzymatic activity was quantified using screen-printed electrodes (SPE). Once patterned, the SPEs were embedded within a microfluidic chamber and used to study the oxidative burst of a 2D layer of macrophages.

2. Experimental

2.1 Materials and Instrumentation

Superoxide dismutase (SOD, bovine with Cu/Zn reaction centers(McCord and Fridovich 1969)), xanthine oxidase (XOD, Bovine), and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Hypoxanthine disodium salt (HPX) was purchased from MP Biomedicals. Glutaraldehyde (GA, 25% in water) was purchased from Acros Organics. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and all other solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Ag/Ag+ reference electrodes were purchased from CH Instruments. Phorbol 12-Myristate 13-Acetate (PMA) was purchased from L C Laboratories. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was prepared with 50 mM phosphate and 100 mM KCl at pH 7.2.

Custom designed screen-printed platinum electrodes (SPE) were obtained from Pine Research Instrumentation. The SPEs consisted of three layers: a ceramic substrate, screen printed platinum, and a ceramic insulating layer covering the entire chip except for the areas needed for electrochemical detection. Each chip features 5 Pt electrodes: three 1.8 mm2 disks, one 0.08 mm2 band (not used), and one 19 mm2 counter electrode, which were cleaned prior to modification by cycling in 0.5 M sulfuric acid. Amperometric experiments were obtained using a Vanderbilt Institute for Integrative Biosystems Research (VIIBRE) multichannel multipotentiostat at a potential of +0.6 V vs. a Ag/AgCl (2M KCl) reference electrode.(Lima et al. Unpublished) Voltammetric measurements were collected on a CHI 660a potentiostat from CH Instruments with a picoamp booster and faraday cage.

Profilometry measurements were made using a Veeco Dektak Profilometer. Plasma treatment was achieved with a Harrick Plasma cleaner.

Enzymes were printed with a Fujifilm Dimatix materials printer. The maximum voltage used was 25.0 V, and the frequency of the pulses was maintained at 23 kHz. Spot spacing was kept uniform at 45 µm over a square print area of 2 mm2.

UV/Vis measurements were taken in a 1.4 mL quartz Spectrocell cuvette and recorded with a Cary 100 BioSpectrophotometer. The absorbance of solutions of XOD, HPX, xanthine (XAN), and uric acid (UA) in PBS were all taken at a concentration of 0.2 µM and compared with the mixture of HPX with XOD (0.1 and 0.2 µM respectively).

2.2 Enzymatic Sensor Fabrication

SOD films were cast onto the SPEs using one of two methods: hand-cast or IJP. For the hand-cast, BSA was dissolved in PB (50 mM phosphate with no KCl at pH 7.2) at a concentration of 62 mg/mL. SOD was dissolved in the PB-BSA solution at a concentration of 5000 U SOD/mL PB-BSA. GA was added to this solution at a concentration of 1 µL GA/250 µL PB-BSA. The solution was hand-cast using a pipette tip onto each of the 1.8 mm2 disk electrodes.(Eklund et al. 2004)

For the IJP, the SOD-PB-BSA solution was made at the same concentrations as the hand-cast solution. This solution was added to the ink-jet cartridge (10 pL print volume). Instead of mixing the SOD PB-BSA solution with GA where it would begin crosslinking, a solution of 1% of the 25% GA in water was prepared in another cartridge. The SOD solution was printed first, followed by the GA solution. After drying, both hand-cast and IJP electrodes were stored in PBS at 20 °C.

2.3 Superoxide Production and Sensor Calibration

XOD (0.1 µM at 0.6 U/mg) was used to convert HPX (1–6 µM) to uric acid (pKa=5.8), which produces two molar equivalents of superoxide for calibration of the SOD electrode.(Bonini et al. 2004; Endo et al. 2002; Hamasaki et al. 2008) The two superoxide radicals produced are oxidized by SOD to generate current at the electrode. The concentrations used in these calibrations are much lower than the saturation behavior of bovine erythrocyte SOD, 0.21 mM O2 •−.(Terech et al. 1983)

2.4 Cell Culture

The adherent murine macrophage cell line, RAW 264.7 (ATCC), was maintained in continuous culture with Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (Mediatech), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Atlanta Biologicals), 1% sodium pyruvate (Mediatech), and 0.1% Gentamicin Sulfate (BioWhittaker) at pH 7.40 in a 5% CO2, 37 °C atmosphere. Subculturing was performed by washing twice with Dulbecco’s PBS (DPBS, Atlanta Biologicals) without calcium and magnesium salts and then by adding 5 mL of culture media to the flask. A cell scrapper was used to dislodge cells from the flask.

2.5 Development of PDMS Microfluidic Devices

Microfluidic design and photolithography patterning of SU8 wafers was performed in collaboration with VIIBRE. PDMS was poured over the negative SU8 wafer and hardened for a minimum of 2 hours at 55 °C (10:1 PDMS to curing agent). The PDMS was separated from the mold and silanized by exposure to trichloro(1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyl)silane (Sigma Aldrich) under vacuum within a nitrogen glove box for a minimum of 3 hours. The molds were soaked in water overnight and then rinsed with isopropanol and dried. PDMS was poured over this mold, cured, and silanized as previously described. This set of PDMS molds was cured and used as the negative from which all future PDMS microfluidic devices were obtained.

The height of the PDMS devices was determined using profilometry. A new device was poured for every experiment. Inlet/outlet holes were punched with a 1.8 mm diameter stainless steel punch to fit the Tygon tubing (OD 1.78 mm, ID 1.02 mm). PDMS devices (128 ± 4 µm in height) were sandwiched to the electrode between two acrylic plates. To seal the PDMS to the SPE ceramic surface, a friction fitting was created using nuts and bolts at the four corners of the plates. The electrode is connected to a downstream 2 M Ag/AgCl reference electrode (Molecular Devices).

2.6 Comparison of PDMS treatment for increased cell growth

Cell growth on PDMS was achieved through laminin or collagen cellular adhesion layers or through plasma treatment. Collagen was adhered to the PDMS at 7.5 µg/cm2 (50 µg/mL in 0.1 M HCl) for one hour at room temperature. Laminin was adhered to plasma treated (30 s) PDMS at 10 µg/cm2 (10 µg/mL in media) for one hour at room temperature. After each treatment, the PDMS surface exposed to approximately 5×104 cells prior to incubation under normal culture conditions. Cell growth and confluency was confirmed 12 hours later through visual microscopic inspection. When no adhesion layer was used, the PDMS device was plasma treated (30 s) prior to plating the cells (3×105 cells).

Cell adhesion was tested in a microfluidic environment by sealing the PDMS device to a modified SPE and suspending the macrophages directly above the SPE as shown in Schematic S-1. After one hour of fluid flow, the PDMS was removed from the microfluidic device and visually inspected. Both laminin and plasma treated PDMS had less than 30% cell loss from stripping during either clamping or fluid flow, while collagen had about 90% cell loss, resulting from weakened interactions between the collagen and the PDMS once the cells adhered. For this reason, the plasma treated PDMS, without an adhesion layer, was used for the remainder experiments to prevent introduction of additional variables.

2.7 Testing Cellular Responses with PDMS Microfluidic Devices

Electrochemical cellular responses were obtained using amperometric i-t at a potential of +0.6 V. Flow of the media (20 µL/min) was controlled with a Harvard Apparatus PicoPlus syringe pump. LabVIEW (version 8.5) controlled pump flow by incorporation of time delay within a While Loop to control flow/stop-flow (Figure S-1). The media was warmed to 37 °C with a Watlow temperature controller with silicone rubber heaters.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Characterization of SOD enzyme film

The SOD films were characterized using voltammetry and amperometry. A standard redox couple, potassium ferricyanide, was used to determine if the resistance associated with the SPE might prevent reversible electron transfer (Figure S-2). While slight variations in peak separation (ΔEp) were seen at higher scan rates, the average ΔEp was calculated to be 72 mV at a scan rate (υ) of 5 mV/s. The ratio of peak currents (ipa/ipc, anodic and cathodic respectively) had a mean value of 0.83, indicating reversible or quasi-reversible behavior of the ferricyanide redox couple under these conditions.

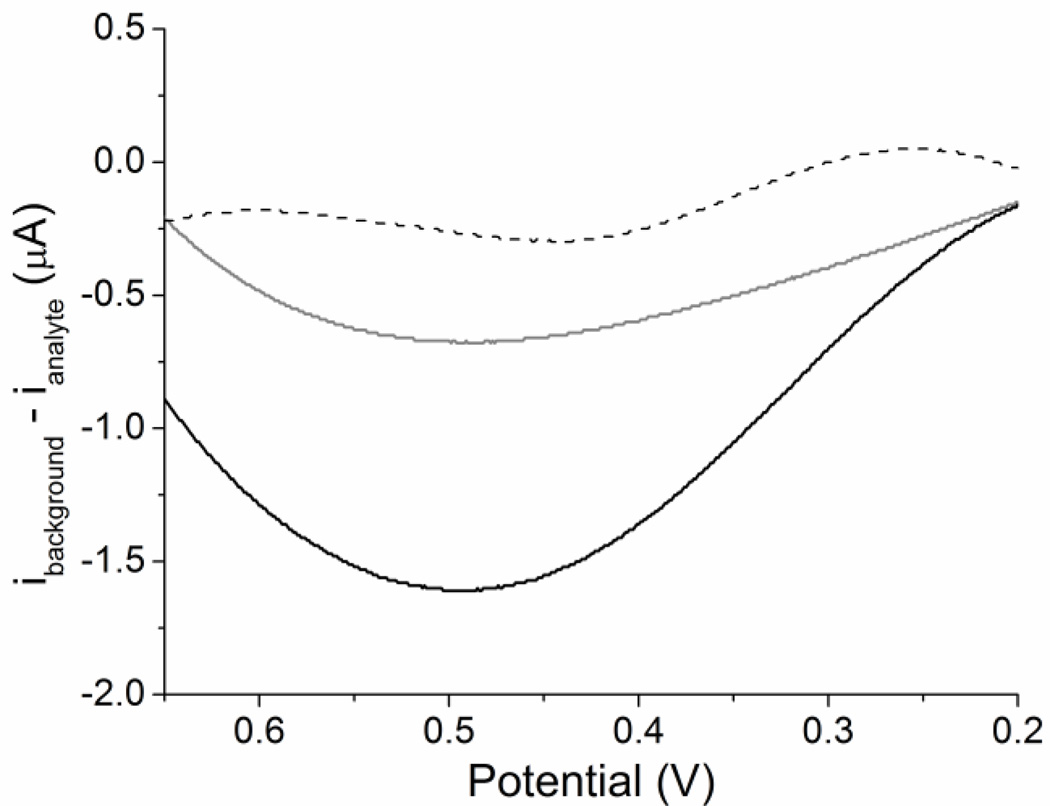

Before electrochemical analysis, UV-Vis spectroscopy was used to confirm production of O2− by XOD (Figure S-3). Superoxide production was confirmed spectroscopically. Voltammetry was performed and the current produced by H2O2 (+0.6 V oxidation) and O2− were compared to determine selectivity (Figure 1). The SOD coated electrode had a greater oxidative peak at +0.6 V for the O2− solution compared to the H2O2 solution (1 µM). Unmodified Pt SPEs were used to determine any changes in current due to non-specific oxidation of O2− at the electrode interface. Both coated and unmodified electrodes detected large increases in reductive current relative to increases in oxidative current. This indicates the ease at which each electrode can reduce oxygen. This irreversible behavior is most likely due to the short half-life of O2− in water.(Andrieux et al. 1987; Dietz et al. 1970; Saha and Ohsaka 2005; Sawyer and Valentine 1981; Vasudevan and Wendt 1995; Wei et al. 2003; Wei et al. 2004) The PBS background was subtracted to determine the relative difference in ROS detection, where a difference between H2O2 and O2− detection for the SOD electrode was 0.93 µA at 0.49 V. The unmodified electrode had a smaller response to O2− than did the SOD coated electrode. The introduction of SOD as part of the electrochemical sensor allows more sensitive detection of O2− than with an unmodified Pt electrode (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The effect of enzymatic activity on oxidative current when exposed to H2O2 or O2−. All LSVs were performed with SPE in PBS at a scan rate of 20 mV/s from 0.2 to 0.7 V. The PBS background was subtracted to yield net current change which is shown here. The net response of an unmodified Pt electrode to O2− (dashed line, O2− produced with 1 µM XOD and 100 µM HPX) is compared with the response of a SOD electrode to O2− (black line, O2− produced with 1 µM XOD and 100 µM HPX). These electrodes were compared with the response of the SOD electrode in H2O2 (grey line, 1 µM H2O2). A net difference of 0.93 µA at 0.49 V was seen between the response of the SOD electrode in O2− and H2O2.

3.2 Comparison of IJP and hand-cast enzyme deposition

In developing the sensor, reproducible and consistent fabrication of electrodes was a paramount consideration. Consequently, we compared two independent enzyme depositions methods: hand-cast and IJP (Figure S-4). Using IJP, the size of the printed droplets on the SPEs was determined using profilometry (Figure S-5). The droplets could not be sized on the Pt portion of the SPE due to surface roughness (Figure S-5A), but they could be sized on the ceramic (Figure S-5B). The droplets had an average width of 42.7 ± 1.0 µm with an average spacing of 4.4 ± 0.6 µm. Each droplet was higher along the edges, 325.6 ± 14.0 nm, and lower in the middle, 240 ± 14 nm, consistent with the pinning phenomena of a drying drop. This correlates to an approximate volume of 0.41 pL or 4% of the 10 pL drop volume, the rest composed of water. The SOD-BSA-PBS solution is composed of 6% SOD-BSA.

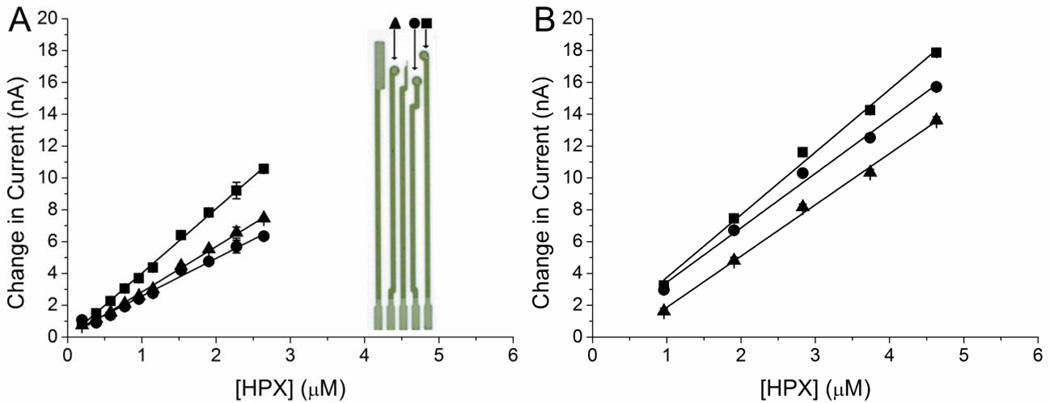

The activity of the IJP droplets were amperometrically compared to drop-cast SOD coated electrodes. Both methods were calibrated using solutions of XOD (0.1 µM) with step-wise additions of HPX (1–6 µM) using the 3 SPE disk electrodes. The current at each concentration was determined by taking an average of two minutes of data, data collected approximately 7 minutes after the addition of HPX. (Figure 2) The coefficient of variation (CV) for the sensitivities was 28% for hand-cast films and 11% for IJP films (Table 1). The CV among electrodes over an 8 day period for the handcast films was 14, 22, and 19% for days 1, 5, and 8 respectively, compared to 11, 8, and 6% CV for the printed films. The average slope remained consistent indicating no loss of enzymatic activity with time for hand-cast or IJP. The average slopes calculated across the 8 days were 3.3 ± 0.7 nA/µM HPX for hand-cast and 3.9 ± 0.5 nA/µM HPX for IJP. Using Student’s t-test at a 95% confidence level, these slopes are not statistically different.

Figure 2.

Amperometric calibration of hand-cast and IJP SOD biosensors. The handcast film (A) demonstrates greater deviation in slope (3.1 ± 0.9 nA/µM HPX, 28% RSD) compared with (B) electrodes coated with a printed film (3.5 ± 0.4 nA/µM HPX, 11% RSD). The inset (A) is a schematic showing the SPE, with each SOD coated electrode designated with a square, circle or triangle, used in the calibration curves. The counter electrode and an unused 0.08 mm2 band electrode are also shown.

Table 1.

Comparison of IJP and hand-cast methods of SOD deposition.

| IJP | Hand-cast | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (nA/µM HPX) | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.9 |

| LOD (µM HPX) | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.10 ± 0.03 |

| Km (mM) | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.24 |

| Vmax (µA) | 0.47 ± 0.14 | 0.89 ± 0.78 |

To determine whether or not enzymatic activity was lost in the printing process, the Michaelis-Menten constants for the two electrodes were compared using a Lineweaver-Burk plot.(Lineweaver and Burk 1934; Michaelis and Menten 1913) The handcast film was calculated to have an apparent Km of 0.25 ± 0.24 mM with a Vmax of 0.89 ± 0.78 µA. Given the large variability resulting from hand cast films, these estimates of Km and Vmax are deemed inaccurate. The uniform deposition performance of IJP resulted in much less variability in electrode fabrication. The IJP was seen to have a Km of 0.11 ± 0.04 mM with a Vmax of 0.47 ± 0.14 µA. Literature values for Km were reported as 0.54 mM (Meier et al. 1995) and 1.3 or 3.5 mM (Fee and Bull 1986) at a pH of 9.5 and 9.3 respectively. As the dismutation of oxygen is more efficient at physiological pH, our smaller Km indicates increased affinity for its substrate. This demonstrates that SOD can be IJP with limited loss of enzymatic activity. This also shows that immobilized SOD can achieve dismutation of O2− at reaction rates comparable to solution, creating an efficient and reproducible sensor. This IJP sensor was utilized in all subsequent studies.

3.3 Calibration of the SOD electrode in a microfluidic device

The electrodes were re-calibrated within the microfluidic chamber to account for thin layer mass transfer.(Endo et al. 2002; Hamasaki et al. 2008) The calibration of the SOD sensor was conducted in both continuous and stop-flow conditions, where separate concentrations of HPX and HOD were mixed immediately prior to introduction into the microfluidic chamber for both conditions. (Figure S-6) (Eklund et al. 2003; Eklund et al. 2004; Eklund et al. 2006). With an increase in HPX concentration, O2− production increases the oxidation occurring at the electrode which increases current. For the stop-flow measurements, the baseline current was subtracted from the peak current yielding a net decrease in oxidative current. The decrease in current is the results of the high rate of O2− dismutation without the constant renewal of O2− via fluid flow. Thus, the convection limited current is higher than the diffusion current. The calibration for continuous flow was y = (0.43 ± 0.01) x + (3.14 ± 0.23), while stop-flow had a lower sensitivity, y = (0.24 ± 0.04) x + (0.66 ± 0.67). A larger sensor response was therefore achieved with continuous flow measurements.

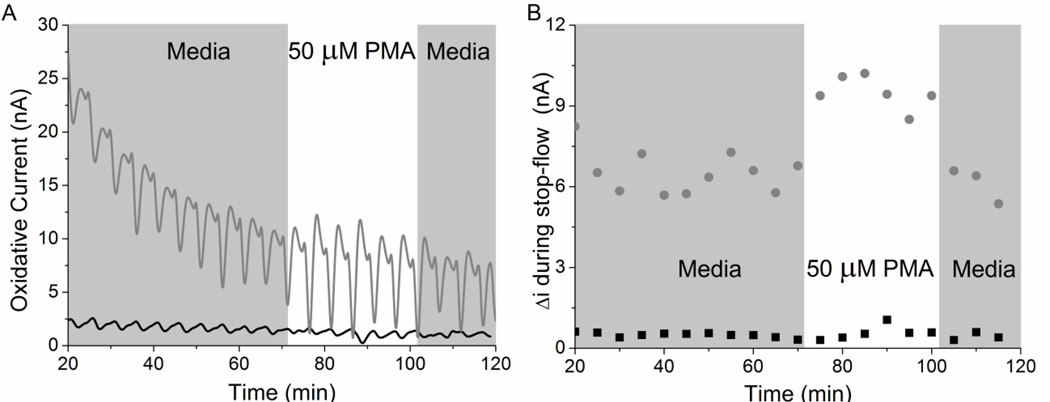

3.4 Macrophage oxidative response to PMA in a microfluidic device

Cellular response to PMA, a known promoter of oxidative burst, was studied in microfluidic devices.(Costa Rosa et al. 1995; Siems et al. 1997) Two microfluidic devices were prepared and exposed to PMA simultaneously (Figure 3). One device contained no cells, while the other was plasma treated and incubated overnight with 5×105 cells. The cellular response to PMA was similar to the HPX/XOD calibration response. The cells were examined using stop-flow fluid pumping as can be seen in the raw data (Figure 3A, 210-s of flow/90-s of stop-flow). A Fourier transform low pass filter (0.005 Hz) was required in order to reduce pump noise and achieve a good average baseline current. The initial decrease in oxidative current may represent the slow loss of cellular activity in the microfluidic device in serum-free media. The average stop-flow current was determined by subtracting the baseline current from the peak current, 6.5 ± 0.8 nA for the chamber containing cells. The average stop-flow current upon exposure to PMA was 9.5 ± 1.2 nA, which is a percent increase in current of 46 ± 19%. Since the substrate concentration (20 ± 7 µM) is much smaller than Km (0.11 ± 0.04 mM), the production of O2− can be compared to the linear calibration curve of O2− produced in the microfluidic device (Figure S-6). While previous studies have reported immediate levels of O2− production, on the time scale of 10 seconds, this study reports the level of O2− that is sustained post-oxidative burst until the removal of the effector, PMA. The initial burst is known to produce femtomolar levels of O2− per cell per second, in the first 10 seconds after stimulus (Amatore et al. 2006). In this study, the sustained burst for thirty minutes during continual stimulus is shown to increase O2− production by 8.8 ± 3.2 attomoles/cell/sec. While the first 10 seconds is not seen due to the stop-flow and noise levels, the sustained response of multiple cells is detected for the first time.

Figure 3.

Macrophage response to PMA exposure in a PDMS microfluidic device. Two chambers were run concurrently where one chamber had no cells (black) and the other had 5×105 macrophages (grey). (A) The raw amperometric response of macrophages over two hours. (B) The absolute change in current during stop-flow, where the baseline current is subtracted from the peak current. The change in current (B) corresponds to an increase of O2− production by 9 ± 3 attomoles/cell/sec.

Using the combination of microfluidics and SPEs, we have determined cellular macrophage oxidative response from the average of multiple cellular responses. This study demonstrates a microfluidic device for the detection of oxidative burst from a 2D layer of cells. With this reproducible SOD electrode, these microfluidic devices can be used to further the study of oxidative burst, where a group of cells can now be studied as opposed to the previous measurements on single cells. The additional electrodes on the SPE allow for the addition of multiple sensors in the electrode array, thus increasing the wealth of information about real-time cellular responses.

4. Conclusions

A new SOD electrode was developed for the detection of O2−. The electrode was calibrated in a bulk solution with an established limit of detection of 0.10 and 0.19 µM O2− (hand-cast and printed), with enhanced selectivity towards O2− over H2O2 shown with linear sweep voltammetry. A comparison of the fabrication methods demonstrated that materials deposition IJP produced a more reproducible and stable electrode. The enzymatic activity of SOD was retained during the materials printing process. This electrode was tested in bulk solutions and further incorporated into a microfluidic device. The detection of macrophage oxidative burst using a SPE in a microfluidic environment provided a method for analyzing sustained macrophage oxidative response. HPX/XOD was used to demonstrate the requisite constant renewal of O2− via fluid flow, without which current becomes diffusion limited. Exposure to PMA generated an oxidative response, which was detected in a microfluidic device. This new reproducible IJP SOD electrode combined with new microfluidic designs will pave the way for improved electrochemical studies of oxidative responses.

Highlights.

A selective superoxide enzyme electrode was designed that can discriminate superoxide from peroxide and measure superoxide concentrations generated by a test xanthine oxidase system.

Ink-jet printing of the SOD enzyme resulted in much smaller relative standard deviations between electrodes which allowed for accurate and precise Michaelis Menton kinetics.

Real-time cellular oxidative burst was measured using selective superoxide dismutase coated electrodes.

This novel electrochemical sensor provides an in vitro platform for further study of metabolic response upon pathogenic invasion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (UO1 AI 061223) and in part by the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (HDTRA1-09-1-0013). This work was made possible by collaborations with the Vanderbilt Institute of Integrative Biosystems Research and Education and the Vanderbilt Institute for Nanoscale Science and Engineering. The authors wish to express their gratitude to Phillip Samson and David Schaffer of VIIBRE for the design of the microfluidic channel and SU-8 photolithography.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Leslie A. Hiatt, Email: leslie.hiatt@vanderbilt.edu.

Jennifer R. McKenzie, Email: jennifer.robin.mckenzie@gmail.com.

Leila F. Deravi, Email: lderavi@seas.harvard.edu.

Reese S. Harry, Email: sreeseharry@hotmail.com.

David W. Wright, Email: david.wright@vanderbilt.edu.

References

- Amatore C, Arbault S, Bouton C, Coffi K, Drapier J-C, Ghandour H, Tong Y. ChemBioChem. 2006;7(4):653–661. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatore C, Arbault S, Chen Y, Crozatier C, Tapsoba I. Lab Chip. 2007;7(2):233–238. doi: 10.1039/b611569a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatore C, Arbault S, Bouton C, Drapier J-C, Ghandour H, Koh ACW. ChemBioChem. 2008a;9(9):1472–1480. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatore C, Arbault S, Ferreira DCM, Tapsoba I, Verchier Y. J. Electroanal Chem. 2008b;615(1):34–44. [Google Scholar]

- Amatore C, Arbault S, Koh ACW. Analytical Chemistry. 2010;82(4):1411–1419. doi: 10.1021/ac902486x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrieux CP, Hapiot P, Saveant JM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1987;109(12):3768–3775. doi: 10.1021/ja035268f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdichevsky Y, Khandurina J, Guttman A, Lo YH. Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical Sensors and Materials. 2004;97(2–3):402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Bodas D, Khan-Malek C. Microelectronic Engineering. 2006;83(4–9):1277–1279. [Google Scholar]

- Bonini MG, Miyamoto S, Di Mascio P, Augusto O. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(50):51836–51843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406929200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikkaveeraiah BV, Liu H, Mani V, Papadimitrakopoulos F, Rusling JF. Electrochemistry Communications. 2009;11(4):819–822. doi: 10.1016/j.elecom.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun AL. Nature Nanotechnology. 2009;4(11):698–699. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2009.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa Rosa LF, Curi R, Murphy C, Newsholme P. Biochem J. 1995;310(Pt 2):709–714. doi: 10.1042/bj3100709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1999;232(1–2):3–14. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(99)00146-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deravi LF, Gerdon AE, Cliffel DE, Wright DW. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007;91(11):113114/113111–113114/113113. [Google Scholar]

- Deravi LF, Sumerel JL, Sewell SL, Wright DW. Small. 2008;4(12):2127–2130. doi: 10.1002/smll.200800536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devadoss A, Burgess JD. Langmuir. 2002;18(25):9617–9621. [Google Scholar]

- Di J, Peng S, Shen C, Gao Y, Tu Y. Biosens Bioelectron. 2007;23(1):88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Risio S, Yan N. Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 2007;28(18–19):1934–1940. [Google Scholar]

- Dietert RR, Golemboski KA. Poult. Sci. 1998;77(7):990–997. doi: 10.1093/ps/77.7.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz R, Forno AEJ, Larcombe BE, Peover ME. J. Chem. Soc. 1970;(B(5)):816–820. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Cliffel DE, Kozlov E, Prokop A, Wikswo J, Baudenbacher F. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2003;496(1–2):93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Taylor D, Kozlov E, Prokop A, Cliffel DE. Anal. Chem. 2004;76(3):519–527. doi: 10.1021/ac034641z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund SE, Snider RM, Wikswo J, Baudenbacher F, Prokop A, Cliffel DE. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2006;587(2):333–339. [Google Scholar]

- Endo K, Miyasaka T, Mochizuki S, Aoyagi S, Himi N, Asahara H, Tsujioka K, Sakai K. Sens. Actuators, B. 2002;83(1–3):30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Fee JA, Bull C. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1986;261(28):13000–13005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Nature. 2000;408(6809):239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ges IA, Baudenbacher F. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2010;25(5):1019–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grune T, Davies KJ. Mol. Aspects Med. 2003;24(4–5):195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamasaki T, Kashiwagi T, Imada T, Nakamichi N, Aramaki S, Toh K, Morisawa S, Shimakoshi H, Hisaeda Y, Shirahata S. Langmuir. 2008;24(14):7354–7364. doi: 10.1021/la704046f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay JA. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue KY, Ino K, Shiku H, Kasai S, Yasukawa T, Mizutani F, Matsue T. Biosensors & Bioelectronics. 2010;25(7):1723–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2009.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima EA, Snider RM, Reiser RS, McKenzie JR, Eklund S, Cliffel DE, Wikswo JP. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Lineweaver H, Burk D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1934;56(3):658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Majumder N, Bhattacharjee S, Bhattacharyya S, Dey R, Guha P, Pal NK, Majumdar S. Scand. J. Immunol. 2008;67(4):329–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2008.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord JM, Fridovich I. J. Biol. Chem. 1969;244(22):6049–6055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier B, Michel C, Saran M, Huttermann J, Parak F, Rotilio G. Biochemical Journal. 1995;310:945–950. doi: 10.1042/bj3100945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis L, Menten ML. Biochem. Z. 1913;49:333–369. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters J. Cell Host & Microbe. 2008;3(6):399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radi R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101(12):4003–4008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307446101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha MS, Ohsaka T. Electrochimica Acta. 2005;50(24):4746–4751. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer DT, Valentine JS. Accounts of Chemical Research. 1981;14(12):393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Sia SK, Whitesides GM. Electrophoresis. 2003;24(21):3563–3576. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siems WG, Capuozzo E, Verginelli D, Salerno C, Crifo C, Grune T. Free Radical Research. 1997;27(4):353–358. doi: 10.3109/10715769709065774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokic-Lazic D, Minteer SD. Biosens Bioelectron. 2008;24(4):939–944. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2008.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terech A, Pucheault J, Ferradini C. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1983;113(1):114–120. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)90439-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida K. Prog Lipid Res. 2003;42(4):318–343. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(03)00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan D, Wendt H. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 1995;392(1–2):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Ji X, Dang X, Hu S. Bioelectrochemistry. 2003;61(1–2):51–56. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5394(03)00059-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y, Dang X, Hu S. Russian Journal of Electrochemistry (Translation of Elektrokhimiya) 2004;40(4):400–404. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.