summary

Detection of DNA methylation has produced promising results as biomarkers for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). However, current panels are limited by an insufficient number of sensitive and specific tumor markers. MicroRNAs (miR) play an important role in tumorigenesis, and may represent a novel panel of molecules for the development of cancer biomarkers. We investigated methylation of three miRNA promoter sites of miR-9 (miR-9-1, miR-9-2, miR-9-3) in 107 human head and neck tissue samples and controls. We found methylations of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 were higher in oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas than that in laryngeal carcinoma, achieving a combined sensitivity of 63% and 56%, respectively, for these two tumor types, compared to 21% for the laryngeal carcinoma. Quantitative PCR of miR-9 showed reduced expression associated with methylation of miR-9 in tumor tissues. To investigate the functional consequences of miR-9 methylation, we found that miR-9 methylation is correlated with miR-9 expression level in human HNSCC cell lines. Demethylation treatment using 5-aza-deoxycytidine restored its expression in a miR-9 methylated human HNSCC cell line UM-SCC22A. Furthermore, cell proliferation and viability was significantly inhibited, while PTEN expression was elevated after transfection of miR-9 into the UM-SCC22A cell line. In summary, our results suggest that methylations of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 are sensitive and specific biomarkers for HNSCC, particularly for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas. In addition, miR-9 may function as a tumor suppressor in HNSCC through inhibition of cell proliferation and elevation of tumor suppressor PTEN.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Methylation, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Biomarkers

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), including cancer of the oral cavity, oropharynx, and larynx, was seen in over 48,000 new patients in 2009 in the US.1 Despite ongoing advances in treatment, only slight improvements have occurred in 5-year survival for patients with oral cavity cancer in the past 30 years (53% increased to 60%), and laryngeal cancer has actually become less survivable (67% down to 64%). Over half of these patients are present with regional or distant disease, and their prognosis is accordingly worse (53% and 28% at 5 years, respectively). This is in contrast to 5-year survival for all cancers increasing by 16% in the same time period.1 It is believed that more accurate and sensitive detection of HNSCC would result in improved survival.2

Biomarkers may be the key for earlier detection and improved therapy. The two biomarkers of commonly use in HNSCC patients are human papilloma virus (HPV) and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).3 HPV is frequently utilized for prognostic information, and EGFR status is helpful for targeted therapy and treatment response.3 Other biomarkers include p53 status for molecular margin assessment and for early diagnosis.4 Epigenetic markers, particularly promoter methylation represent a group of biomarkers possessing several advantages: (1) DNA methylation yields a positive signal, which is easier to detect than an ascent event in cancer cells. In addition, tumor cell-derived DNA methylation can be specifically detected in a high non-tumor cell background. This is particularly useful when it is utilized in body fluids such as serum, sputum, saliva, or buccal swab. (2) Compared to mutation searching, which usually occurs at multiple sites in a particular gene, DNA methylation usually occurs over the same region of the gene, such as the promoter, which greatly simplifies the design and interpretation of screening tests. (3) Compared to expression assays, DNA methylation is relatively stable and impervious to fluctuations in physiological state and sample-collection conditions. Taken together, DNA methylation has been proven to be an ideal approach for early detection and screening of many cancers including HNSCC.5,6

Numerous gene promoter regions have been described as differentially methylated in HNSCC compared to normal tissue.6 While the ideal screening assay would be expected to have 100% sensitivity and specificity, even a moderately sensitive and highly specific panel could be helpful. Epigenetic studies such as methylation-specific PCR (MS-PCR) generally function better in tissue samples, and lose certain degree of sensitivity when applied to saliva or serum samples. Currently, inadequate numbers of highly specific methylation markers for HNSCC prevent their clinical applications. The best described markers for oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal HNSCC commonly range from a sensitivity of 20–60%.3,6,7 Recently, there have been an increase in interest in using a promoter methylation of microRNAs to provide additional assays and to improve the overall sensitivity of methylation screening panels for human cancers,8 including HNSCC.9,10 For example, using MS-PCR of the promoter region of miR-137 achieved 21% sensitivity to HNSCC with oral rinse samples and 16% sensitivity with paraffin-embedded HNSCC DNAs.10

MicroRNAs (miRNA) are small, non-coding RNAs involved in the regulation of gene expression through either the repression of translation or direct cleavage of the target mRNA.11 Growing evidence demonstrates the role of miRNA in development and progression of numerous malignancies,11 including HNSCC.12 In addition to the dysregulation of miRNA expression in human cancers, the epigenetic silencing of miRNAs has been recently reported in various cancers.8 For example, Lujambio et al. described the methylation of miR-9 in human cancer cell lines and multiple human cancers, and claimed that miR-9 methylation correlated with tumor metastasis, including HNSCC.13 Similar findings of miR-9 methylation were also reported in other solid tumors, including cancers from breast,14 pancreas,15 colon,16 and kidney.17 Taken together, these reports suggest a suppressor role of miR-9 in tumor development and progression. However, several studies reported controversial findings in which miR-9 is overexpressed in certain cancers, and promotes tumor progression and metastasis,18,19 suggesting a tumor promoter role of miR-9 in tumor development and progression. To further clarify the role of miR-9 in HNSCC at each stage, we examined the methylation status of miR-9 in primary tumor tissues, their adjacent mucosa, and lymph node metastases. We further correlated the methylation status and expression of miR-9 in HNSCC tumor tissues and cell lines. Lastly, we performed functional assays and explored miR-9 target genes to investigate the potential mechanisms of miR-9 methylation in HNSCC. Our result showed that miR-9 is indeed methylated in HNSCC patients, and has a great potential for molecular diagnosis of HNSCC, particularly for oral cavity and oropharyngeal carcinomas. In addition, miR-9 possesses a role of tumor suppressor, at least partly, through inhibition of cell proliferation and upregulation of PTEN.

Material and methods

Human tumor samples

For the analysis of human HNSCC tumor specimens, we used 107 human surgical samples from both the Oregon Health & Science University and the University of Colorado Denver under the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved protocols from each institution. The samples included a total of 52 squamous cell carcinomas from various anatomical sites of the head and neck region, 7 HNSCC lymph nodes grossly and microscopically positive for malignancy, 36 samples of adjacent histologically normal mucosa from cancer patients, and 12 mucosal controls from patients unaffected by cancer (Table 1). Age and genders of patients from which the samples derived were recorded. We extracted DNA and RNA from the samples using mechanical homogenization and standard manufacturer protocols. DNA was extracted using both the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen) or the ZR Genomic DNA™-Tissue Mini-Prep kit (Zymo), and RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen). DNA and RNA samples were quantitated using the Nanovue spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare).

Table 1.

Sample list of HNSCC tumor, adjacent, and normal tissues.

| Tumor tissues from HNSCC patients | 59 |

| Oral cavity | 30 |

| Oropharynx | 9 |

| Larynx | 13 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 7 |

| Adjacent tissues from HNSCC patients | 36 |

| Normal mucosa | 33 |

| Normal lymph node | 3 |

| Normal tissues from non-cancer patients | 12 |

| Normal mucosa | 9 |

| Normal tonsil | 3 |

DNA methylation analysis

Bisulfate conversion of DNA (500 ng/reaction) was accomplished using the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold™ Kit (Zymo) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. MS-PCR was performed on miR-9-1, miR-9-2, and miR-9-3 with primers previously reported by Lujambio et al.13 MS-PCR of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 was performed using the GoTaq™ DNA Polymerase (Promega) with 30 and 28 cycles reactions, respectively. MS-PCR of miR-9-2 was accomplished with AmpliTaq Gold® (Applied Biosystems) with 40 cycles reaction. Each reaction was composed of known positive and negative water controls. Following amplification, PCR products were run on a 2.0% agarose gel with 1:20000 GelRed™ (Biotium), and were visualized with UV transillumination (Kodak).

miRNA expression analysis

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) for miR-9 was performed on 7 HNSCC samples and 8 normal control samples. The 7 HNSCC samples were all noted on MS-PCR to be either doubly methylated (miR-9-1 and miR-9-3) or triply methylated (miR-9-1, miR-9-2, miR-9-3). Control samples were not methylated on these assays. qPCR was accomplished using TaqMan® MicroRNA Assays (Applied Biosystems), using a small RNA-specific stem-loop RT primer, followed by a PCR amplification from the resultant cDNA sample.

Cell culture, transfection, and MTT assay

Human HNSCC cell lines UM-SCC10A and UM-SCC22A were obtained from Dr. Thomas Carey of the University of Michigan under approval of Material Transfer Agreement. Cells were maintained at DMEM + 10% FBS, and were passed approximately once a week. For the demethylation treatment, cells were cultured with or without 10 lM 5-aza-deoxycytidine (Sigma) for 5 days. The day before transfection, the cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 105/ml density. 50 nM of dsRNA mimicking human mature miR-9 (miR-9 mimic) or control non-specific miRNAs (Dharmacon) were transfected individually into cell lines using DharmaFect (Dharmacon) according to the manufacture’s instruction. One day after transfection, medium were changed with regular DMEM + 10% FBS. Cells were either harvested to extract RNAs for expression analysis at 48 h, or underwent MTT assay at 5 days after transfection. Five millimolars of MTT (Sigma) were added 3 h before lysed by DMSO, and read at OD570 nm using a microplate reader (BMG LABTECH).

Statistical analysis

Correlations between clinicopathologic features and methylation status were evaluated using Fisher’s exact test. A p-value was deemed statistically significant if it was less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was carried out in coordination with the Department of Biostatistics, University of Colorado at Denver.

Results

Methylation of miR-9 in HNSCC samples

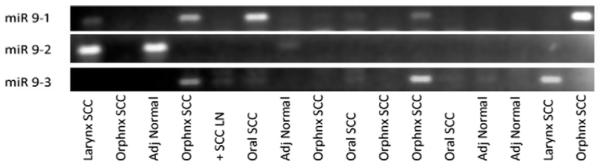

A total of 107 human tissue samples were analyzed using MS-PCR on promoter regions of miR-9-1, miR-9-2 and miR-9-3 (Table 1). The average age and ratio of male to female of HNSCC patients was 64.2 years and 5:1 compared to 58.4 years and 4:1 in the non-cancer patients. The average age and gender ratios for the oral cavity SCC, oropharyngeal SCC, and laryngeal SCC were 62.7 and 5:1, 63.2 and 4.5:1, and 61.8 and 3.25:1, respectively. MS-PCR bands using primers specific to methylation were visually scored for each sample as present or absent as exemplified in Fig. 1. Overall, methylation of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 demonstrated good sensitivity and excellent specificity for HNSCC samples of all reactions (Table 2a and b), i.e. the sensitivity of miR-9-1 methylation was 44% with 98% specificity (Table 2a), and that of miR-9-3 methylation was 27% with 100% specificity (Table 2b). In combination of miR9-1 and miR9-3 methylation results, there tests yielded a total of 51% sensitivity and 98% specificity HNSCC detection among the 107 samples assayed (Table 2c). We failed to correlate the methylation status of miR-9-1 or miR-9-3 with clinical stage, histologic grade, or lymph node metastasis. However, we observed a significantly higher sensitivity of either miR-9-1 methylation (57%), or in combination with miR9-3 methylation (63%) for oral cavity carcinomas compared to those in laryngeal carcinomas (15% for miR--1 methylation, and 23% for the combined miR9-1 and miR9-3 methylation, p = 0.0103 and p = 0.0217, respectively). Assessment of miR-9-2 methylation yield less satisfactory results. Twelve samples of miR-9-2 methylation were excluded due to the poor reactions. In the end, the sensitivity and the specificity of using miR-9-2 methylation for HNSCC was 42% and 54%, respectively.

Figure 1.

An agarose gel example of MS-PCRs of miR-9-1, miR-9-2 and miR-9-3 in various human HNSCC tumor samples and adjacent normal mucosa.

Table 2.

Sensitivity and specificity of miR-9 methylation in HNSCCs.

| Sample type | Cases of methylation | Total cases | Sensitivity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Sensitivity and specificity of miR-9-1 methylation in HNSCCs | |||

| HNSCC | 26 | 59 | 44 |

| Oral cavity | 17 | 30 | 57* |

| Oropharynx | 5 | 9 | 56 |

| Larynx | 2 | 13 | 15* |

| Ln** metastasis | 2 | 7 | 29 |

| Specificity (%) |

|||

| Histologic normal | 1 | 48 | 98 |

| Adjacent normal | 1 | 36 | 97 |

| Control normal | 0 | 12 | 100 |

| (b) Sensitivity and specificity of miR-9-3 methylation in HNSCCs | |||

| Sensitivity (%) |

|||

| HNSCC | 16 | 59 | 27 |

| Oral cavity | 11 | 30 | 37 |

| Oropharynx | 2 | 9 | 22 |

| Larynx | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| Ln** metastasis | 1 | 7 | 14 |

| Specificity (%) |

|||

| Histologic normal | 0 | 48 | 100 |

| Adjacent normal | 0 | 36 | 100 |

| Control normal | 0 | 12 | 100 |

|

(c) Sensitivity and specificity of combination of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 methylation in HNSCCs | |||

| Sensitivity (%) |

|||

| Histologic HNSCC | 30 | 59 | 51 |

| Oral cavity | 19 | 30 | 63* |

| Oropharynx | 5 | 9 | 56 |

| Larynx | 3 | 13 | 23* |

| Ln** metastasis | 3 | 7 | 43 |

| Specificity (%) |

|||

| Histologic normal | 1 | 48 | 98 |

| Adjacent normal | 1 | 36 | 97 |

| Control normal | 0 | 12 | 100 |

A significant difference in sensitivity between these two subtypes (p < 0.05).

Ln, lymph node.

miR-9 expression correlates with pan-methylation of miR-9-1, miR-9-2, and miR-9-3

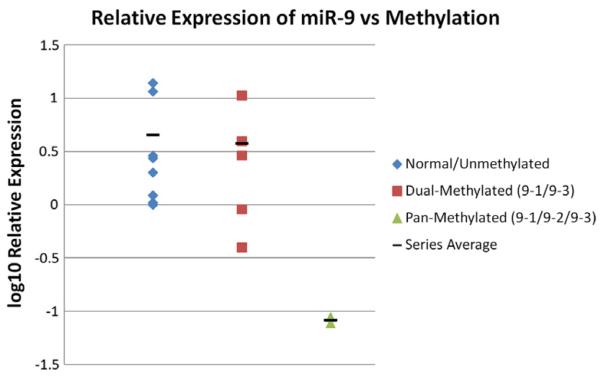

To investigate if the methylation of miR-9 correlates with gene expression, we performed qPCR to measure mature miR-9 expression level in HNSCC samples with methylation of miR9-1 and miR9-3 (n = 5), pan-methylation of miR9-1, miR9-2, miR9-3 (n = 2) and without methylation (n = 8). Compared to the expression level of miR-9 in the normal unmethylated samples, a slightly reduced of expression was observed in samples bearing dual methylation of miR-9-1 and miR9-3. However, an over ten-fold decrease below the lower end of the normal range of miR-9 expression was observed in samples with pan-methylation of miR-9-1, miR-9-2, and miR-9-3 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Correlation of mature miR-9 expression with methylation status of miR-9-1, miR-9-2 and miR-9-3 in human HNSCC tumor samples. Methylation of all promoter regions was associated with marked suppression of miR-9 expression.

Functional analysis of miR-9 methylation using human HNSCC cell lines

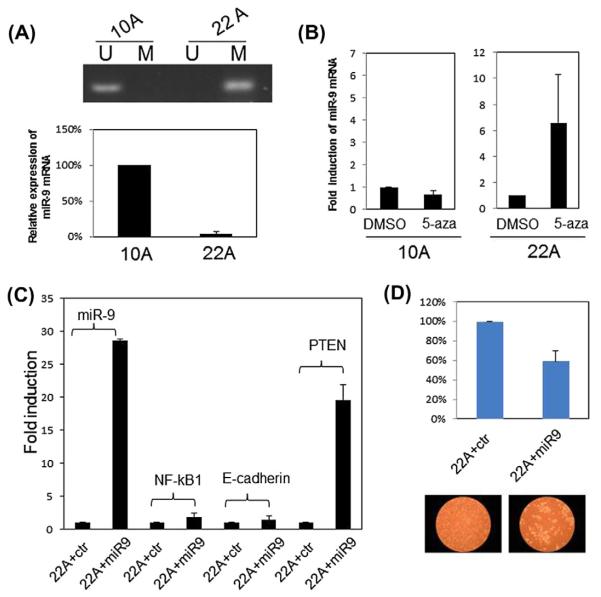

To further investigate the functional consequences of miR-9 methylation in HNSCC, we analyzed a miR-9 methylated cell line UM-SCC22A and a miR-9 unmethylated cell line UM-SCC10A. Consistent with the data from tumor tissues, miR-9 mRNA expression was reduced to about 4% in the miR-9 methylated cell line UM-SCC22A compared to the miR-9 unmethylated cell line UM-SCC10A (Fig. 3A). Demethylation treatment using 5-aza-deoxycytidine restored about 6-fold increase of miR-9 expression in the UM-SCC22A cell line, while it did not significantly affect miR-9 expression in the UM-SCC10A cell line (Fig. 3B), suggesting that miR-9 methylation contributes to the reduced expression of miR-9. To examine the potential target genes of miR-9, we transfected miR-9 mimic into the UM-SCC22A cell line. We first measured the expression level of the reported miR-9 targets NF-jB, and E-cadherin. Expression level of either gene was not significantly affected although the expression level of miR-9 increased about 25 folds after the miR-9 mimic transfection. However, the expression of tumor suppressor PTEN increased about 20-fold after the miR-9 mimic transfection (Fig. 3C). Last, we measured cell proliferation and viability after the miR-9 mimic transfection in the UM-SCC22A cell line. As shown in Fig. 3D, MTT assay revealed a significantly decrease to ~60% in the miR-9 mimic transfected cells compared to the control miRNA transfected cells, suggesting a suppressive role of miR-9 in cell proliferation and viability.

Figure 3.

Functional analysis of miR-9 methylation in HNSCC cell lines. (A) upper panel: Methylation of miR-9 as revealed by MS-PCR, U: unmethylated primers M: methylated primers. Lower panel: Expression of miR-9 as examined by qRT-PCR. (B) Restoration of miR-9 expression upon 5-aza-cytidine treatment in the UM-SCC22A cell line as revealed by qRT-PCR. (C) qRT-PCR result of examining potential target genes of miR-9 upon miR-9 mimic transfection. 22A + ctr: UM-SCC22A cell line transfected with control miRNA mimic. 22A + miR9: UM-SCC22A cell line transfected with miR9 mimic. Data was collected 48 h after transfection. (D) Cell proliferation and viability examined by MTT (upper panel) and morphology under microscope (lower panel). Data was collected 5 days after transfection. All quantitation data in Fig. 3 are the average of at least two separated experiments.

Discussion

miR-9 functions as tumor suppressor in HNSCC

Methylation of miR-9 was originally reported in three independent studies of genome-wide searching for cancer-associated micr-oRNA methylation. Through a search of microRNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis, Lujambio et al. identified miR-9 methylation in multiple human cancer cell lines, and also found it in several primary human tumor tissues including breast, colon, melanoma, head and neck, lung, and breast.13 A similar study reported that epigenetic silencing of miR-9-1 was increased in invasive breast carcinomas. In addition, a good correlation between quantitative methylation level and reduced expression of miR-9 were also reported in this study.14 Finally, a study revealed a high percentage methylation of miR-9-1 with reduction or absence of its expression in human pancreatic cancer.15 Methylation of miR-9 was further reported in breast cancer with xenoestrogen exposure,20 in colorectal cancer,16 and in renal cell carcinoma with correlation of metastatic recurrence.17 In addition, reduced or loss of miR-9 expression was reported in multiple human cancers although the methylation status of miR-9 was not investigated.21-25 Furthermore, functional studies with miR-9 restoration in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo has been associated with cell growth inhibition and apoptosis and resulted tumor suppression through either NF-jB or p53 pathways.20,23-25 Our current study found a tumor specific methylation of miR-9 in HNSCCs, although we could not correlate miR-9 methylation with clinical pathological data, particularly on tumor metastasis, given the relatively small sample size and incomplete information of clinical data. However, we did correlate miR-9 methylation with anatomical site of HNSCC, i.e. higher methylation rate in oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas compared to that in laryngeal carcinomas. In addition, we also correlated miR-9 methylation with its expression, and the suppressive role of miR-9 on cell proliferation and viability. Unfortunately, we failed to validate the potential target genes of miR-9, i.e. NF-jB and E-cadherin, in our study. Instead, we found a positive correlation between miR-9 and PTEN expression level. Although the connection between miR-9 and PTEN seems indirect, the upregulation of PTEN after miR-9 restoration further supports a tumor suppressor role of miR-9 in HNSCC, and investigation of how miR-9 regulates PTEN is a very interesting question for further pursue. Taken together, our study suggests that miR-9 functions as a tumor suppressor in HNSCC and miR-9 methylation may be a common event in multiple human cancers.

Dysregulation of miR-9 may be context- and stage-specific in human cancers

Although our study and reports cited in the discussion above suggest a tumor suppressor role of miR-9 in tumorigenesis, contradictory reports suggest a tumor promoter role of miR-9 in several cancers at certain circumstances.18,19,26,27 Instead of reduced expression of miR-9 in multiple human cancers, miR-9 was found to paradoxically overexpressed in breast, cervical, brain, and endometrial cancers.18,19,26,27 One common feature of miR-9 overexpression seems to correlate with cancer progression, poorly prognosis, and metastasis.18,19,26,27 However, miR-9 methylation and/or reduced expression was also observed in metastatic or recurrent human cancers.13,17,21 Several studies suggest that miR-9 is activated by c-Myc and is able to suppress E-cadherin to promote cancer metastasis.18,28 miR-9 was also suggested to regulate b-catenin and VEGF indirectly and its overexpression induces tumor angiogenesis.18 In endometrial cancer, miR-9 was one of the microRNAs associated with downregulation of the tumor suppressor FOXO1.27 Although we failed to correlate miR-9 methylation with the clinical pathological data of our HNSCC patients, miR-9 methylation were found across our HNSCC samples in all different stages, including tumor metastases. Whether the dual role of miR-9 as either tumor suppressor or promoter observed in human cancers is cancer type-specific, or stage-specific need further investigation.

Methylation of miR-9 is a biomarker in oral and oropharyngeal cancers and may improve future diagnostic panels

Methylation of miRNAs in human cancers represents a novel class of molecules, which has great potential to develop as biomarkers. Development of DNA methylation markers for HNSCC is one of the most promising strategies and has been intensively studied in the past.3,6 However, the sensitivity and specificity of the existing panel of DNA methylation markers are still less satisfactory.3,6 In addition, there is no evaluation of miRNA methylation markers in HNSCC diagnosis and prognosis. In this study, we found that methylation of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 is a specific biomarker in HNSCC tumor samples, particularly for the oral cavity and oropharyngeal carcinomas, and has potentials for molecular diagnosis. Our data concur with that described by Lujambio et al.13 in the specificity of methylation of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 in HNSCC. We were unsuccessful in validating their experience with miR-9-2 and found it to be less reliable in separation of malignant and normal samples using a conventional MS-PCR method. We are currently developing quantitative MS-PCR methods and hoping that quantitative MS-PCR might yield more sensitive and specific results.

In summary, our study showed that methylations of miR-9-1 and miR-9-3 represent relatively sensitive and highly specific markers for HNSCC, especially for oral and oropharyngeal carcinomas. Our hope is that such study would increase interest in including the methylated microRNAs into the existing panels of HNSCC biomarkers to improve their sensitivity and specificity. Such panels should also be evaluated in easy accessible biomaterials, such as serum, saliva, or fine needle aspirates.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Molecular Profiling Resources of the Departments of Dermatology and Otolaryngology, Oregon Heath & Science University for providing part of the human HNSCC samples. The authors also thank Dr. Thomas Carey of the University of Michigan Otolaryngology Department for providing human HNSCC cell lines UM-SCC10A, and UM-SCC22A. This study was supported by the Academic Enrichment Fund of the University of Colorado Denver to Dr. Shi-Long Lu.

Abbreviations

- miR

microRNA

- HNSCC

head and neck squamous cell carcinoma

- MS-PCR

methylation-specific PCR

- HPV

human papilloma virus

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mao L, Hong WK. Papadimitrakopoulou VA. Focus on head and neck cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:311–6. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mydlarz WK, Hennessey PT, Califano JA. Advances and perspectives in the molecular diagnosis of head and neck cancer. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2010;4:53–65. doi: 10.1517/17530050903338068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJ, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MS, Lee J, Sidransky D. DNA methylation markers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:181–206. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ha PK, Califano JA. Promoter methylation and inactivation of tumour-suppressor genes in oral squamous-cell carcinoma. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:77–82. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70540-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho AL, Jeronimo C, Kim MM, Henrique R, Zhang Z, Hoque MO, et al. Evaluation of promoter hypermethylation detection in body fluids as a screening/diagnosis tool for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:97–107. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iorio MV, Piovan C, Croce CM. Interplay between microRNAs and the epigenetic machinery: an intricate network. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1799:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kozaki K, Imoto I, Mogi S, Omura K, Inazawa J. Exploration of tumor-suppressive microRNAs silenced by DNA hypermethylation in oral cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2094–105. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langevin SM, Stone RA, Bunker CH, Grandis JR, Sobol RW, Taioli E. MicroRNA-137 promoter methylation in oral rinses from patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck is associated with gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:864–70. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iorio MV, Croce CM. MicroRNAs in cancer: small molecules with a huge impact. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5848–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.0317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tran N, O’Brien CJ, Clark J, Rose B. Potential role of micro-RNAs in head and neck tumorigenesis. Head Neck. 2010;32:1099–111. doi: 10.1002/hed.21356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lujambio A, Calin GA, Villanueva A, Ropero S, Sanchez-Cespedes M, Blanco D, et al. A microRNA DNA methylation signature for human cancer metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13556–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803055105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lehmann U, Hasemeier B, Christgen M, Muller M, Romermann D, Langer F, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of microRNA gene hsa-mir-9-1 in human breast cancer. J Pathol. 2008;214:17–24. doi: 10.1002/path.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Omura N, Li CP, Li A, Hong SM, Walter K, Jimeno A, et al. Genome-wide profiling of methylated promoters in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1146–56. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.7.6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandres E, Agirre X, Bitarte N, Ramirez N, Zarate R, Roman-Gomez J, et al. Epigenetic regulation of microRNA expression in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2009;125:2737–43. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildebrandt MA, Gu J, Lin J, Ye Y, Tan W, Tamboli P, et al. Hsa-miR-9 methylation status is associated with cancer development and metastatic recurrence in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29:5724–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ma L, Young J, Prabhala H, Pan E, Mestdagh P, Muth D, et al. MiR-9, a MYC/ MYCN-activated microRNA, regulates E-cadherin and cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:247–56. doi: 10.1038/ncb2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu X, Schwarz JK, Lewis JS, Jr, Huettner PC, Rader JS, Deasy JO, et al. A microRNA expression signature for cervical cancer prognosis. Cancer Res. 2010;70:1441–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsu PY, Deatherage DE, Rodriguez BA, Liyanarachchi S, Weng YI, Zuo T, et al. Xenoestrogen-induced epigenetic repression of microRNA-9-3 in breast epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5936–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laios A, O’Toole S, Flavin R, Martin C, Kelly L, Ring M, et al. Mol Cancer. 2008;7:35. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-7-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo H, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Ning B, Guo J, et al. Down-regulated miR-9 and miR-433 in human gastric carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2009;28:82. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-28-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Po A, Di Marcotullio L, Tosi E, Espinola MS, et al. MicroRNA profiling in human medulloblastoma. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:568–77. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo LM, Pu Y, Han Z, Liu T, Li YX, Liu M, et al. MicroRNA-9 inhibits ovarian cancer cell growth through regulation of NF-kappaB1. FEBS J. 2009;276:5537–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wan HY, Guo LM, Liu T, Liu M, Li X, Tang H. Regulation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB1 by microRNA-9 in human gastric adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nass D, Rosenwald S, Meiri E, Gilad S, Tabibian-Keissar H, Schlosberg A, et al. MiR-92b and miR-9/9/ are specifically expressed in brain primary tumors and can be used to differentiate primary from metastatic brain tumors. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:375–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Myatt SS, Wang J, Monteiro LJ, Christian M, Ho KK, Fusi L, et al. Definition of microRNAs that repress expression of the tumor suppressor gene FOXO1 in endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:367–77. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Y, Wu J, Wu SH, Thakur A, Bollig A, Huang Y, et al. Expression profile of microRNAs in c-Myc induced mouse mammary tumors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;118:185–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]