Abstract

BACKGROUND

Recently lymph node yield (LNY) has been endorsed as a quality measure of CC resection adequacy. It is unclear whether this measure is relevant to all ages. We hypothesized that total lymph node yield (LNY) is negatively correlated with increasing age and overall survival (OS).

STUDY DESIGN

The Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database was queried for all non-metastatic CC patients diagnosed from 1992–2004 (n=101,767), grouped by age (<40, 41–45, 46–50, and in 5-year increments until 86+ years). Proportions of patients meeting the 12 LNY minimum criterion were determined in each age group, and analyzed with multivariate linear regression adjusting for demographics and AJCC 6th Edition stage. Overall survival (OS) comparisons in each age category were based on the guideline of 12 LNY.

RESULTS

Mean LNY decreased with increasing age (18.7 vs. 11.4 nodes/patient, youngest vs. oldest group, P<0.001). The proportion of patients meeting the 12 LNY criterion also declined with each incremental age group (61.9% vs. 35.2% compliance, youngest vs. oldest, P<0.001). Multivariate regression demonstrated a negative effect of each additional year in age and log (LNY) with coefficient of −0.003 (95% CI −0.003 to −0.002). When stratified by age and nodal yield using the 12 LNY criterion, OS was lower for all age groups in Stage II CC with <12LNY, and each age group over 60 years with <12LNY for Stage III CC (P<0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

Every attempt to adhere to proper oncological principles should be made at time of CC resection regardless of age. The prognostic significance of the 12 LN minimum criterion should be applied even to elderly CC patients.

Keywords: lymph node, quality, colon cancer, outcome metric

INTRODUCTION

Despite continued advances in the multidisciplinary treatment of colon cancer (CC), it remains the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States. The American Cancer Society estimates that there will be 102,900 newly diagnosed CC cases and 51,370 deaths in 2010 alone.1 Following oncological resection, adjuvant chemotherapy is reserved for lymph node positive patients and, at present, recommended on a case-by-case basis for certain high-risk node-negative patients having tumor perforation, low lymph node retrieval, poorly differentiated tumors, and/or T4 lesions.2,3 Despite this multi-modality treatment approach, the outcomes of node-negative patients with CC remain highly variable attributable, in part, to nodal yield at time of operation and pathological staging.

Proper staging, involving adequate resection of the primary tumor with associated draining lymph node basins along with a thorough pathological examination, remains paramount to ensuring appropriate surgical care and selection for adjuvant systemic therapy. However, other factors may also play a role in the subsequent treatment both at the time of and following the operation. Aside from individual surgeon and pathologist variation, patient factors such as underlying co-morbidities, physiological condition at the time of operation, body mass index (BMI), and age often factor into the aggressiveness (both surgical and oncological) with which care is pursued (e.g. extent of resection, selection of adjuvant therapy).4–6 An important factor in therapeutic decisions in CC is patient age, which has been known to add to the considerable variation in the overall management of this disease. These decisions impact both young and old, in view of relevant clinical factors such as ability to tolerate major surgery, mulit-agent systemic therapy, and the ultimate benefit of each weighing into the treatment algorithm.

To determine the adequacy of an oncological resection for CC, the lymph node yield (LNY) examined in the specimen has recently become a defined, widely promulgated quality measure. Furthermore, a consensus including multiple national society and quality forums (supported by the American Board of Surgery, National Cancer Institute and American Society of Clinical Oncology) have emerged endorsing the standard LNY ≥12 as the minimum requirement for number of nodes resected and examined to define adequate staging.7–11 Yet, a low lymph node yield does not necessarily demonstrate a failure of surgeons to adhere to proper oncological principles.12 In the era of pay for performance, transparency of hospital outcomes, and quality metric evaluation, this may result in an inappropriate attribution of low quality to surgeons who are otherwise performing high quality operations. Therefore, it is important to thoroughly explore the different factors that may ultimately impact lymph node retrieval. Previous studies have identified that young age is a predictor for improved lymph node yield following resection, with consistently higher percentages able to achieve this emerging national benchmark of the 12-node minimum.13–16 Conversely, older age has been associated with lower lymph node yield, for somewhat indistinct causes.17,18 Yet, while LNY is a marker for proper resection of CC, it remains unclear whether this measure is relevant to all ages. The goal of the present study was to use a large, population-based data set to help more clearly define what the combined effect of LNY and age ultimately has on CC outcomes as well as determine the impact of age on quality measure adherence in colon cancer. We hypothesized that total lymph node yield (LNY) is negatively correlated with increasing age and overall survival (OS).

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively-collected data.

Outcomes

The primary study endpoints were lymph node yield (LNY) compliance with a 12 LN minimum for surgical resection based on age. The secondary endpoint was overall survival.

Data Source

The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program collects data from 13 regional cancer registries comprising 26% of the US population, which is considered representative of the entire population. A public use set of de-identified data is available to researchers and is considered to be exempt from IRB review. Available data includes patient demographics, primary tumor data, regional nodal data, vital status and survival.

Patient Population

The SEER database was queried for all patients diagnosed with colon adenocarcinoma diagnosed between 1992 and 2004, who had data recorded for the number of lymph nodes examined. Although data collection began in 1977, the number of examined lymph nodes was recorded from 1988. The study population consisted of those undergoing colon resections (ICD-O-3 codes C18.0-C18.9 and C26.0) with a T1–T4 colon cancer without distant metastases (AJCC 6th Edition Stages I–III). Patients were excluded for having insufficient information to determine AJCC 6th Edition cancer stage or number of nodes in the pathologic specimen, having had a prior non-colon cancer, rectal cancer, or AJCC Stage IV disease. Rectal cancers were not included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

All cases were re-staged based on the AJCC 6th Edition staging criteria. Mean, median, and mode of the number of lymph nodes examined were determined. Patients were initially grouped by age (<40 years, 41–45, 46–50, and in 5-year increments until 86+ years). LNY was calculated by age group and compared using ANOVA. Tumors with a primary site of cecum, ascending colon and hepatic flexure were classified as right colon lesions. Left colon tumors encompassed those in the descending colon and splenic flexure. Based on the national guidelines, analysis was further stratified by those with ≥12, and <12 nodes examined. Proportions of patients meeting the 12 LNY minimum criterion in each age group were analyzed by Chi-square testing. Overall survival (OS) comparisons stratified by each age category (65+ versus <65) were based on the current national guideline of 12 LNY using the Kaplan-Meier technique. A hierarchical linear regression model to predict lymph node yield was created with the log(LNY) as the dependent variable. Analyzed variables included patient age category, gender, ethnicity, year of diagnosis, geographical region (by SEER registry), primary colon tumor site, depth of invasion (T-stage), grade, regional nodal status (N-stage), and the total number of nodes examined. Variables were selected using a forward stepwise methodology, using patient demographic factors in the first level, geographical factors in the second level, and tumor characteristics as the final level. We included variables at a significance level of <0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using PASW 18.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago IL). Significance levels were set at P<0.05. All tests were two sided.

Role of the Sponsors

All funding for the study was obtained from intra-mural programs at the USMCI (AB, AS) and the NCI 2R01CA090848 (PI AB).

RESULTS

A total of 101,767 patients met study inclusion criteria, including 48,656 (47.8%) men and 53,111 (52.2%) women (age: mean 69.9 ± 12.8 years; median 72 years). The majority of patients were White (82.2%), while 9.5% were Black, and 8.3% composed other races. Table 1 depicts the representative patient demographics by each age category. By AJCC 6th Edition staging criteria, there were 24,277 (23.8%) Stage I, 41,934 (41.2%) Stage II and 35,606 (35.0%) Stage III patients. By location, the most common primary tumor site was the right colon (47.1%), followed by the sigmoid (32.1%), left colon (10.2%), transverse colon (9.1%), and not otherwise specified (1.5%).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Tumor Characteristics by Age Group (N (Total =101,767))

| Age, y | ≤40 | 41–45 | 46–50 | 51–55 | 56–60 | 61–65 | 66–70 | 71–75 | 75–80 | 81–85 | 86+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 2266 | 2284 | 4038 | 6439 | 8072 | 10578 | 13631 | 16247 | 16335 | 12599 | 9278 |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 51.6% | 50.3% | 51.1% | 53.1% | 55.5% | 54.6% | 53.1% | 49.8% | 44.9% | 39.6% | 31.8% |

| Female | 48.4% | 49.7% | 48.9% | 46.9% | 44.5% | 45.4% | 46.9% | 50.2% | 55.1% | 60.4% | 68.2% |

| Race | |||||||||||

| Black | 14.6% | 15.4% | 14.7% | 14.3% | 12.5% | 11.7% | 10.3% | 8.7% | 7% | 6% | 5.6% |

| White | 72.2% | 72.2% | 74.5% | 75.2% | 78.2% | 79.6% | 80.8% | 83.2% | 85.5% | 87.4% | 89.1% |

| Other/Unknown | 13.2% | 12.4% | 10.7% | 10.5% | 9.1% | 8.7% | 9% | 8.2% | 7.4% | 6.5% | 5.3% |

| % With 12+ LN | 61.9% | 52.4% | 48% | 45.6% | 41.9% | 40% | 38.6% | 37.5% | 38% | 37.5% | 35.2% |

| Mean LN examined (SE) | 18.7 (0.3) | 15.6 (0.2) | 14.3 (0.2) | 13.7 (0.1) | 13 (0.1) | 12.5 (0.1) | 12.2 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) | 12 (0.1) | 11.9 (0.1) | 11.4 (0.1) |

| AJCC 6th Ed Stage | |||||||||||

| I | 16.3% | 18.85 | 23.2% | 24.75 | 25.2% | 25.6% | 25.4% | 25.5% | 24.6% | 21.9% | 19.3% |

| II | 37.2% | 35.6% | 35.2% | 35.1% | 36% | 37.7% | 39.8% | 41.3% | 43.3% | 46.7% | 49.6% |

| III | 46.4% | 45.65 | 41.6% | 40.2% | 38.8% | 36.7% | 34.8% | 33.2% | 32.1% | 31.4% | 31.1% |

LN: Lymph Node

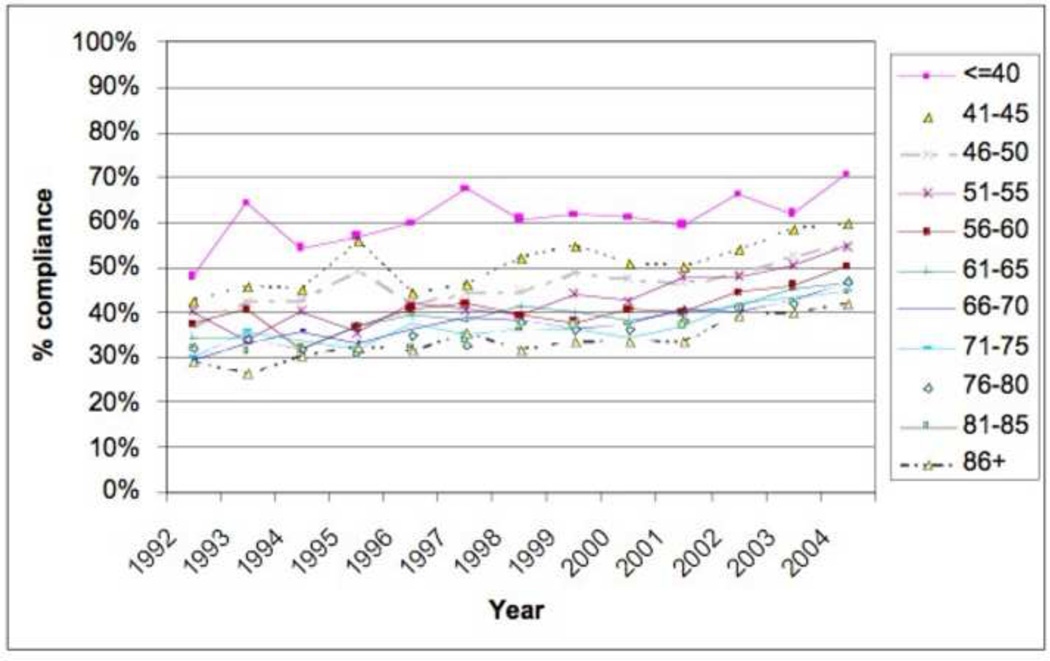

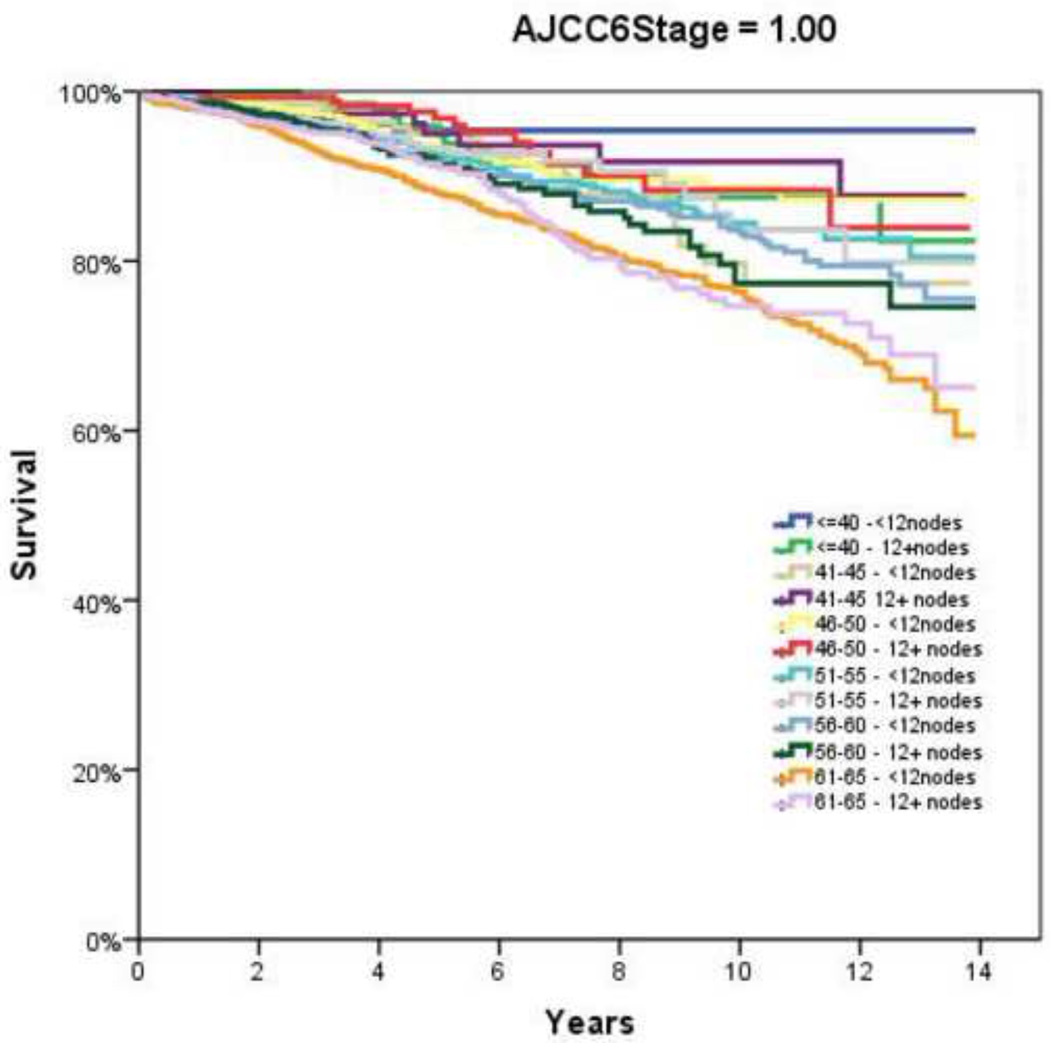

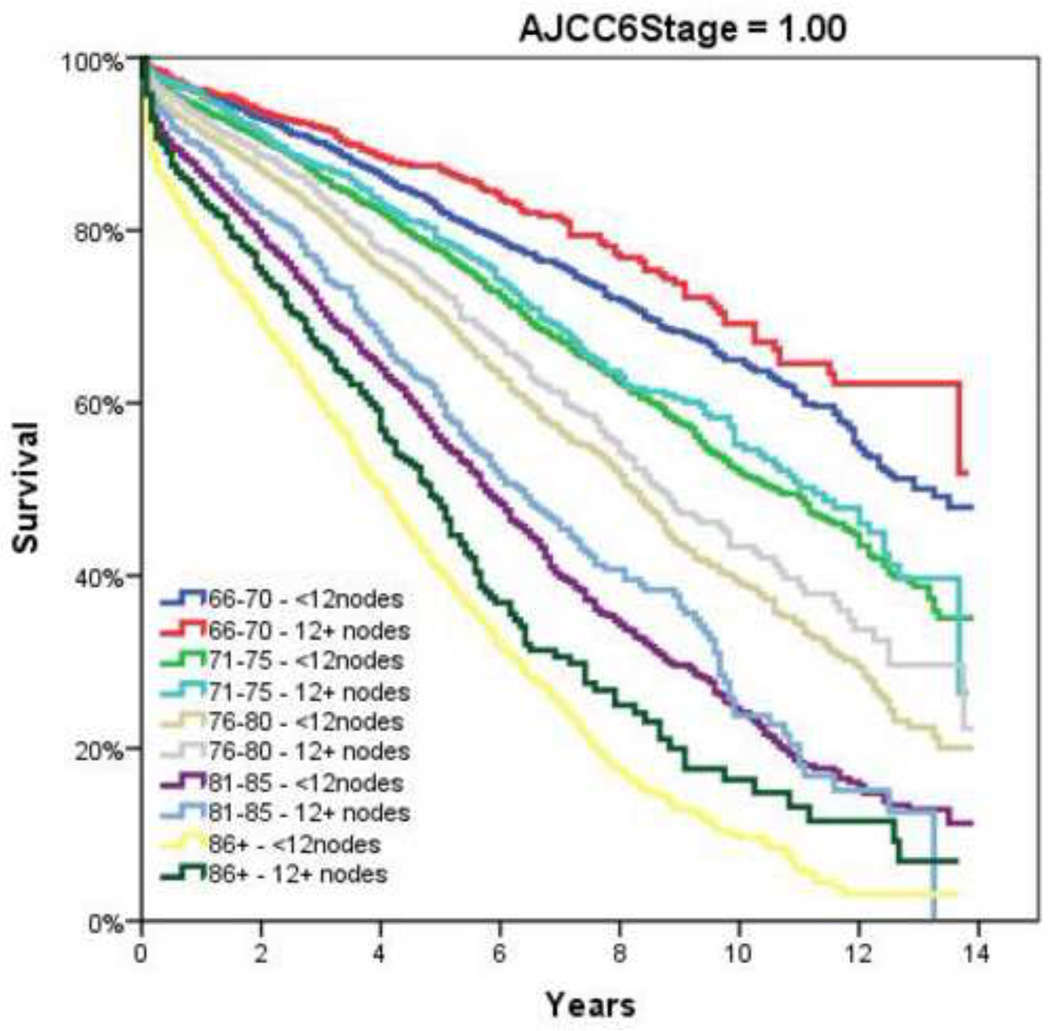

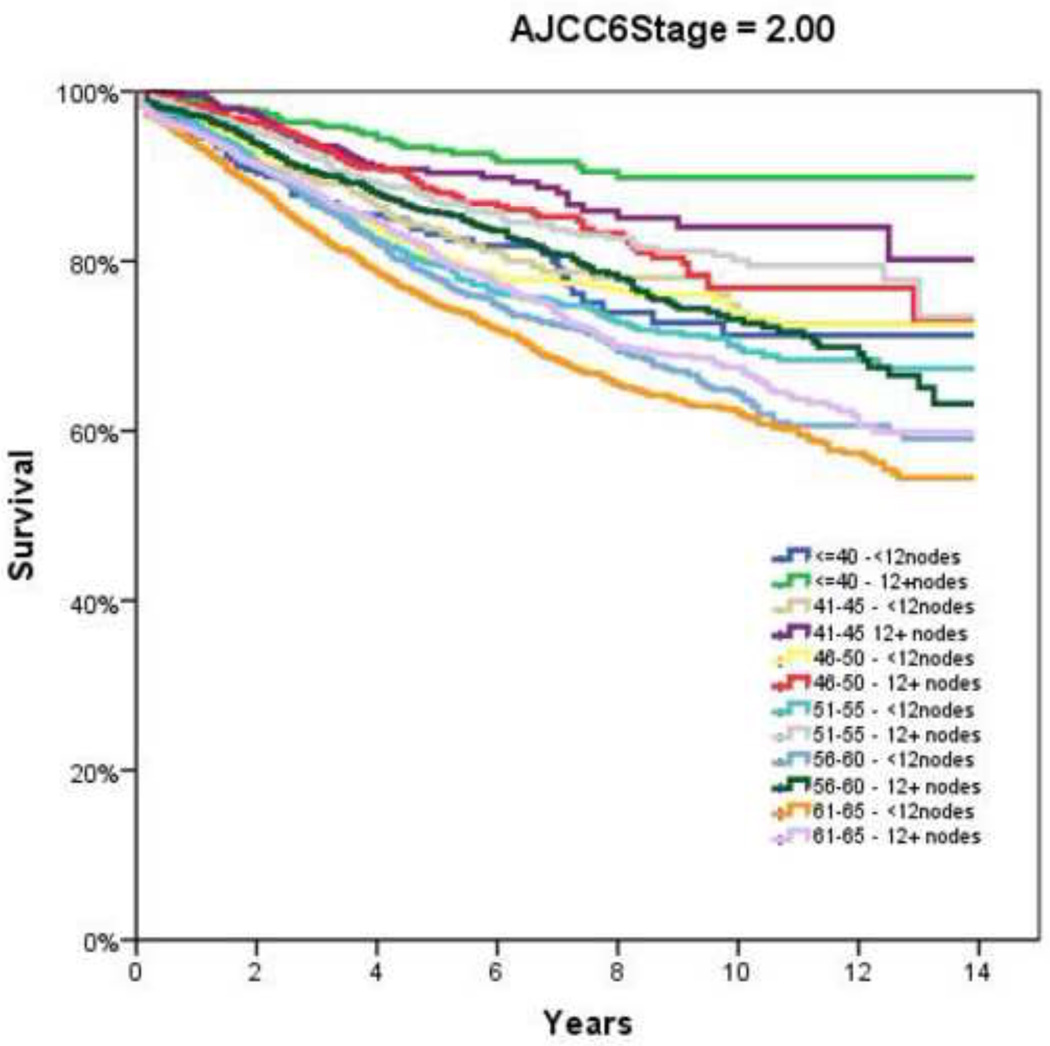

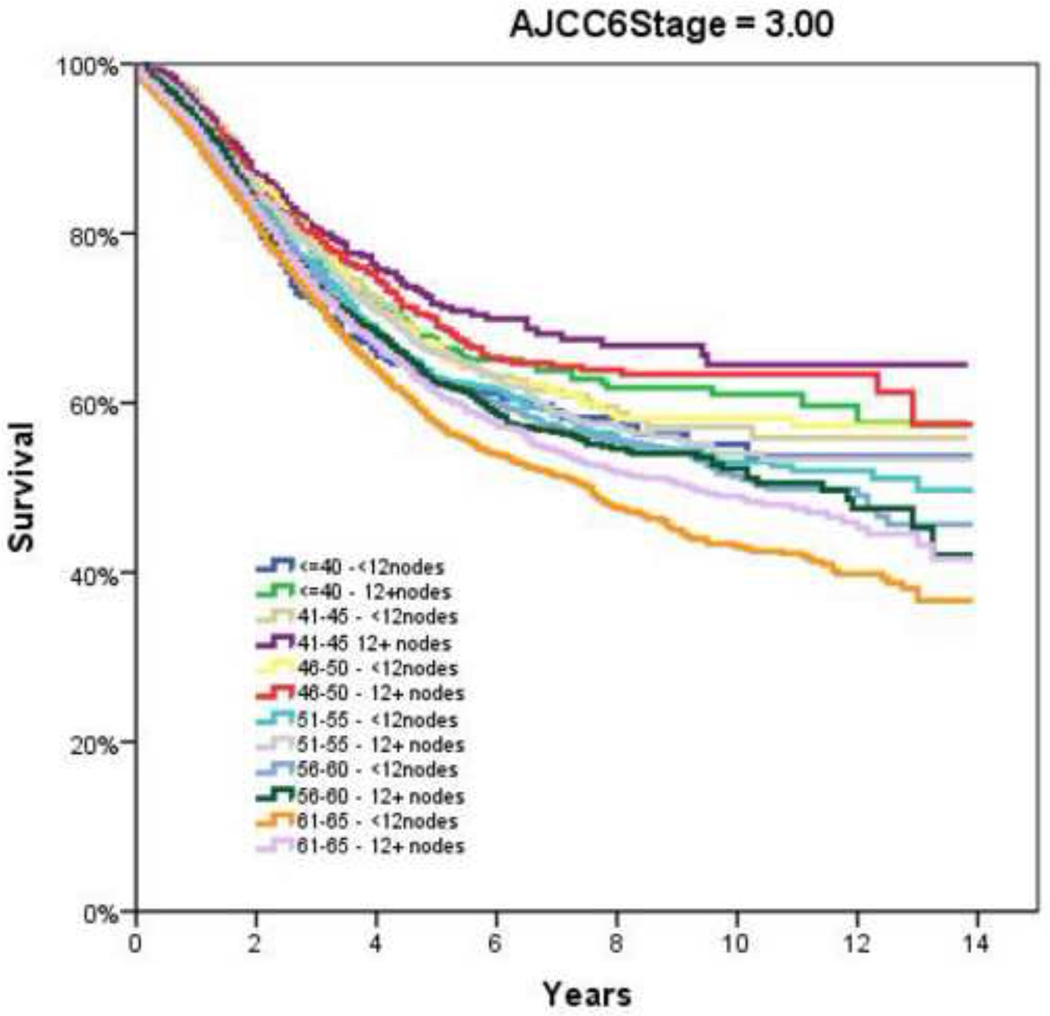

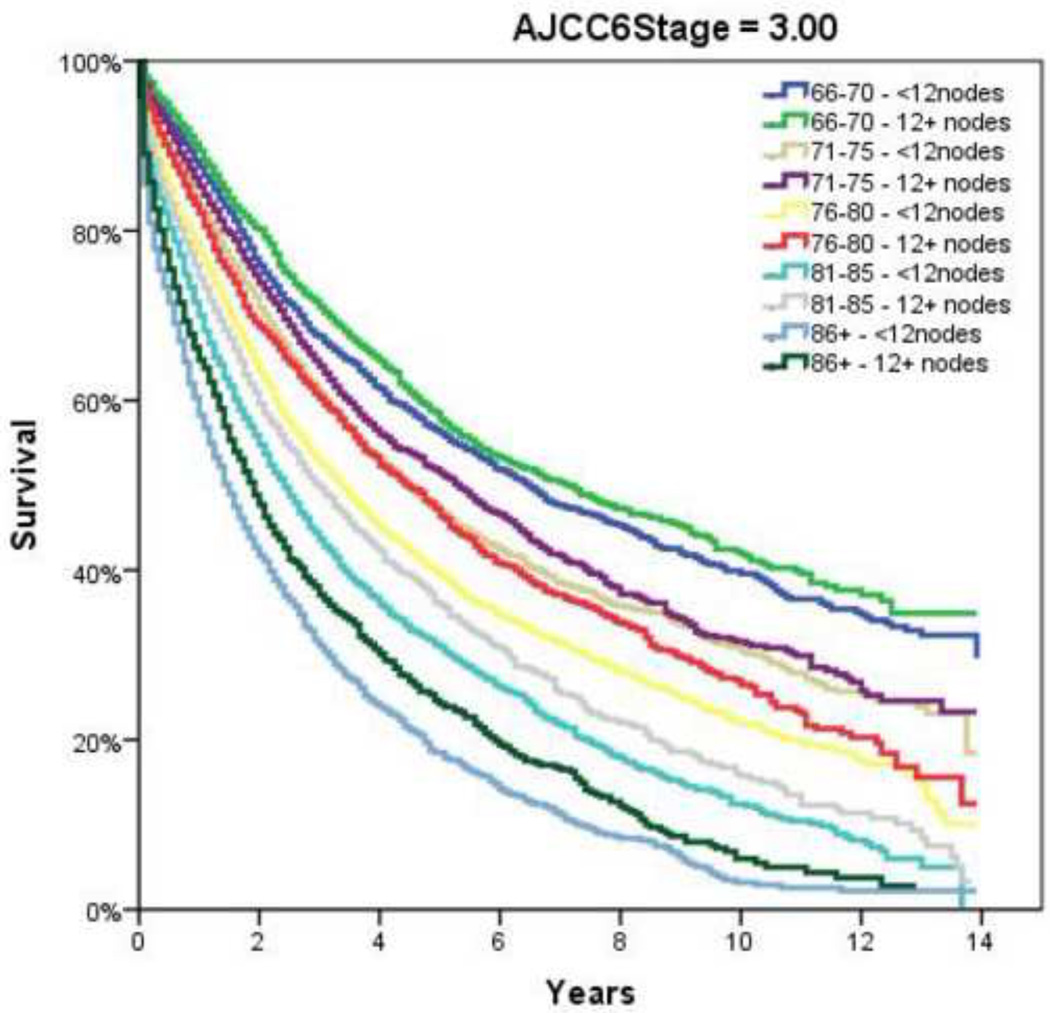

Table 2 demonstrates the LNY per each incremental age category. Mean LNY decreased with increasing age (18.7 vs. 11.4 nodes/patient, youngest vs. oldest group, P<0.001). For the entire cohort, 39.9% had ≥ 12 nodes evaluated in the pathologic specimen, with the most consistent LNY ≥12 nodes identified for patients <40 years (61.9%). The proportion of patients meeting the 12 LNY criterion also declined with each incremental age group (61.9% vs. 35.2% compliance, youngest vs. oldest, P<0.001). Figure 1 demonstrates the proportion of patients compliant with 12+ nodes by year of diagnosis and age throughout the time interval of the study (1992–2004). Within each age category there is a significantly higher proportion of patients meeting the 12 LNY benchmark (1992 vs. 2004, P<0.001). Additionally, in each year the likelihood of meeting the 12 LNY criterion decreased with increasing age (youngest vs. oldest, P<0.001). By tumor primary site, there was significantly higher LNY from right colon lesions than other sites. (Table 3) Multivariate linear regression analysis demonstrated a negative effect of each additional year in age and log (LNY) with coefficient of −0.003 (95% CI −0.003 to −0.002), even after adjusting for gender and AJCC Stage. (Table 4) This translates to an approximately 3.4% decrease in nodal yield for each five year age interval on average. Overall survival (OS), when stratified by AJCC staging and nodal yield using the 12 LNY criterion was lower for all age groups in Stage II CC with <12LNY and each age group over 60 years with <12LNY for Stage III CC (P<0.05). (Figure 2) Finally, Cancer-Specific Survival stratified by AJCC staging, age and LNY demonstrated again significant differences for all AJCC Stage II groups and older patients with Stage III CC. Cancer-Specific Survival for AJCC Stage I patients was similar. (Table 5)

Table 2.

Lymph Node Yield with Increasing Age

| Age Group, y |

N | Mean LNY |

95% Confidence Interval |

% Meeting 12 LNY |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <=40 | 2,266 | 18.7 | 18.2 | 19.3 | 61.9% |

| 41–45 | 2,284 | 15.6 | 15.2 | 16.1 | 52.4% |

| 46–50 | 4,038 | 14.3 | 14.0 | 14.6 | 48.0% |

| 51–55 | 6,439 | 13.7 | 13.5 | 14.0 | 45.6% |

| 56–60 | 8,072 | 13.0 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 41.9% |

| 61–65 | 10,578 | 12.5 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 40.0% |

| 66–70 | 13,631 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 12.4 | 38.6% |

| 71–75 | 16,247 | 12.0 | 11.9 | 12.2 | 37.5% |

| 76–80 | 16,335 | 12.1 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 38.0% |

| 81–85 | 12,599 | 11.9 | 11.8 | 12.1 | 37.5% |

| 86+ | 9,278 | 11.4 | 11.2 | 11.6 | 35.2% |

| Total | 101,767 | 12.6 | 12.5 | 12.6 | 39.9% |

LNY – Lymph Node Yield

Figure 1.

Percentage of Patients Compliant with 12+ Nodes by Year of Diagnosis and Age

Table 3.

Lymph Node Yield by Primary Tumor Site.

| Lymph Node Yield | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Mean | N | Lower bound | |

| Ascending Colon | 14.6 | 17733 | 14.5 | 14.8 |

| Cecum | 13.6 | 24391 | 13.6 | 13.8 |

| Descending Colon | 11.8 | 6245 | 11.6 | 12.1 |

| Hepatic Flexure | 14.4 | 5834 | 14.2 | 14.7 |

| Large Intestine, NOS | 13.6 | 1487 | 12.8 | 14 |

| Sigmoid Colon | 10.4 | 32657 | 10.3 | 10.5 |

| Splenic Flexure | 12 | 4187 | 11.7 | 12.3 |

| Transverse Colon | 12.7 | 9233 | 12.5 | 12.9 |

| Total | 12.6 | 101767 | 12.5 | 12.6 |

NOS- Not Otherwise Specified

Table 4.

Linear Regression of Factors Associated with log(LNY)

| Model | Standardized Coefficients |

95.0% Confidence Interval for B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | P | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |

| Variable | .000 | 1.037 | 1.060 | |

| Age at Diagnosis | −.003 | .000 | −.003 | −.002 |

| Gender | .039 | .000 | .022 | .030 |

| AJCC Stage II | .185 | .000 | .119 | .129 |

| AJCC Stage III | .224 | .000 | .150 | .160 |

AJCC- American Joint Committee on Cancer

LNY – Lymph Node Yield

Figure 2.

Overall Survival by Adherence to ≥12 Node Sampling by Age. A and B, AJCC6 Stage 1; C and D, AJCC6 Stage 2; E and F AJCC6 Stage 3

Table 5.

Cancer-Specific Survival by AJCC Stage, Age and Lymph Node Yield

| AJCC Stage |

Group | P-value vs. <12 nodes |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | <=40 - 12+nodes | .564 |

| 41–45 12+ nodes | .232 | |

| 46–50 - 12+ nodes | .871 | |

| 51–55 - 12+ nodes | .911 | |

| 56–60 - 12+ nodes | .939 | |

| 61–65 - 12+ nodes | .258 | |

| 66–70 - 12+ nodes | .568 | |

| 71–75 - 12+ nodes | .097 | |

| 76–80 - 12+ nodes | .503 | |

| 81–85 - 12+ nodes | .088 | |

| 86+ - 12+ nodes | .687 | |

| 2 | <=40 - 12+nodes | .000 |

| 41–45 12+ nodes | .050 | |

| 46–50 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 51–55 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 56–60 - 12+ nodes | .001 | |

| 61–65 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 66–70 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 71–75 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 76–80 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 81–85 - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 86+ - 12+ nodes | .000 | |

| 3 | <=40 - 12+nodes | .073 |

| 41–45 12+ nodes | .129 | |

| 46–50 - 12+ nodes | .348 | |

| 51–55 - 12+ nodes | .249 | |

| 56–60 - 12+ nodes | .673 | |

| 61–65 - 12+ nodes | .033 | |

| 66–70 - 12+ nodes | .317 | |

| 71–75 - 12+ nodes | .062 | |

| 76–80 - 12+ nodes | .023 | |

| 81–85 - 12+ nodes | .004 | |

| 86+ - 12+ nodes | .041 | |

AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer

DISCUSSION

With the increased emphasis on surgical competence, thoroughness of pathological evaluation, evidence-based medicine, and outcome analysis, it is important that each quality metric applied in clinical practice adequately represents an accurate assessment of care and the population of interest affected by disease. While the 12-node minimum for colon cancer endorsed by a number of key opinion leading organizations has been deemed the “gold standard” both in the United States and internationally, prior large-scale population-based reviews, including the present study, have demonstrated benchmark achievement in <50%.14 There has however been a significant improvement recently in reaching this benchmark as demonstrated in the present study, particularly at NCCN-designated cancer centers with reported rates of compliance exceeding 90%.5,19 This is both clinically relevant and important, as OS benefit for patients with CC has been shown to increase progressively with increasing number of lymph nodes resected and evaluated pathologically in some reports.20,21

Although the 12-node minimum threshold is not necessarily substantiated biologically or mathematically, it represents a reasonable, achievable minimum number of lymph nodes that should be examined following oncological resection of the colon. However, the importance of this LNY cutoff may not apply for all patients across all stages of non-metastatic disease. In fact, the optimal minimum number of lymph nodes to be examined after colon resection remains a topic of controversy. The overall survival impact of this quality measure in colon cancer remains to be definitively determined, especially as it relates to different age groups, though recent data supports LNY as an oncologically relevant metric.11, 14, 21–24 There is no question that success or failure to reach this minimum nodal threshold is not simply patient-factor or hospital facility driven, but likely multi-factorial including tumor specific molecular alterations such as nodal lymphocytic reaction.6, 25–27 Factors identified as having an impact on LNY have included individual surgeon, pathologist, pathology technician, hospital case-volume, site of the primary tumor, and year of resection.28–32 While all of these have been previously validated in single institution or population-based studies, it is important to evaluate the current quality metric to ensure their reliability and reproducibility as it pertains to all patients in which the standard is applied; in this case, young and old patients alike. Consequently, the goal of the present study was to evaluate the impact of age on quality measure adherence of minimum LNY in colon cancer. We hypothesized that total lymph node yield is negatively correlated with increasing age and overall survival.

We identified a negative correlation between advancing age and LNY for patients diagnosed with non-metastatic colon adenocarcinoma who were treated with curative intent. Previous authors have similarly found that increasing age is associated with a decreasing number of lymph nodes examined, although collective comparisons are somewhat hampered by widely varying, somewhat arbitrary, age cutoffs without clear mathematical or oncological basis (i.e., ≤40 vs. >40, <67 vs. >78, >80 years, etc).18, 33, 34 We therefore chose to evaluate patients by grouping both extremes of age (<40, 86+ years), along with 5-year age increments between these two extremes. This allowed us to not only determine trends within each age cohort over the 13-year study period, but also compare the age groupings with one another. Not surprisingly, we identified improvement in LNY within all age categories over the course of the study, likely reflecting added emphasis in recent years on adequate LNY to support accurate staging, as well as increasing awareness of the relationship between LNY and improved survival.21, 26, 35 We also found that within each study year, the LNY for younger patients continued to be significantly higher than older patients (Figure 1).

Speculative reasons for this multi-factorial LNY-associated and age-dependent phenomenon may be related to factors beyond generally accepted surgical and pathological technique. These include a biological decrease in number of evaluable lymph nodes or immunocompetence with older age, or age-dependent lymphocyte transformation of regional lymph node cells. Although difficult to prove, this may essentially represent a reverse causality. This may suggest that taking more lymph nodes doesn’t necessarily yield better results; rather, improved outcomes may result from those people already having more lymph node density. The importance of proper evaluation, and perhaps ultimate impact on OS, however, cannot be overemphasized. For while the exact reasons remain elusive, we were able to identify an independent statistical correlation on multivariate analysis, specifically that overall survival was lower for all age groups in Stage II CC with <12LNY, and each age group over 60 years with <12LNY for Stage III CC. Therefore, with a lack of data to identify other factors, such as biological behavior, to account for these differences in outcome, the goal remains to achieve a 12 LNY minimum when possible.

Although it is enticing to attribute the finding of age-dependent differences in nodal evaluation to surgeon or patient-specific factors, much has been written about the various contributing factors that may account for this disparity. In a recent study of 430 colon cancer resections increasing age itself was associated with a mild negative correlation with respect to overall LNY (r=−0.19, P<0.001).6 The authors concluded factors “out of control of the surgeon” such as patient age may have to be taken into consideration prior to becoming a permanent incentive-based measurement. Quah and colleagues similarly found that younger patients were found to have more nodes retrieved in their specimens (median 18 vs. 14, P=0.001) in a comparison of 68 patients younger than 40 years undergoing colectomy for cancer versus 1,259 patients over 40 years.18 They further found that younger patients were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy, especially in those with Stage II disease (39% vs. 14%, P=0.003). Yet this did not translate into a difference in disease-specific survival (younger versus older: 86% vs. 87%); though 5–year overall survival was higher in the younger cohort (84% vs. 73%, P=0.001). The authors concluded that factors such as nodal retrieval, which was age-dependent, and ultimately treatment differences, especially in node-negative disease, may have contributed to the differences in outcome. Similar to the present study, large population-based studies have shown overall low rates of adequate LN evaluation (≥12 nodes examined), with older patients (≥71 years) less likely to have adequate nodes examined than younger patients (OR = 0.45, 95% CI 0.44–0.47).36 Regarding the 12 LNY minimum benchmark, Baxter and associates also found that those patients less than 50 years old achieved the 12 lymph node minimum in 51% versus only 35% for those over 70 years of age, findings similar to the present study. Yet, many of these previous studies used a single cutoff to define age, which may have impacted their findings. We elected therefore to use 5-year increments to evaluate for trends and provide additional information that may be for unique to certain smaller cohorts.

Notwithstanding the differences in LNY amongst the various age groups over the study period, we furthermore wanted to identify the impact of LNY (<12 vs. 12+ LNs) impact on patient outcomes. We again found that in patients with advanced age, lower LNY was associated with decreased overall survival for both node-positive and node-negative CC. This is similar to the findings of other authors, who identified that decreased lymph node evaluation was associated with worse overall survival, though they did not specifically evaluate the impact of age.15, 21 Yet, this point remains somewhat controversial, as not all have found that number of lymph nodes resected and examined correlates with overall survival. A study out of the Mayo Clinic found that survival was only dependent on the number of nodes positive and independent of the total number of nodes (>12 or 12+) examined for Stage III patients.37 Considering that previous authors have identified a higher frequency of lymph node metastasis in younger patients,17, 38 it may not be the absolute number, but tumor biology that dictates ultimate outcome. Furthermore, Wang and colleagues found the prognostic value of total number of LNs on survival was nullified after stratifying by the lymph node ratio (LNR) of positive to evaluated nodes.23 Chen and associates in a review of the SEER database also found that the lymph node ratio independently estimates survival for those patients with Stage III colon cancer, irrespective of number of nodes examined.39 However, unlike the Wang study, the authors found a statistically significant improvement in overall survival within each LNR stratum for those patients with examination of ≥12 nodes. In the present study, the 12 LNY benchmark continued to have a direct impact on outcome for both Stage II and Stage III disease, with overall survival lower for all age groups in Stage II when the LNY was <12, and each age group over 60 years with <12LNY for Stage III (P<0.05). We also elected to look at Cancer-Specific survival, as overall survival may be confounding, especially in older patients, and found similar Cancer-Specific survival for both Stage II and III disease.

Although the findings in Stage II CC might simply represent a stage migration issue, LNY-dependent survival impact continued to hold up as an independent predictor of overall survival in multivariate analysis, confirming prior reports.40 Additionally, it may represent a difference in treatment with regards to adjuvant therapy with age differences and variations in LNY.41 Hardiman and colleagues have shown that there are disparities in the treatment of those older than 80 compared to younger. This may be secondary to their finding of LNY being significantly lower in those over 80 (11 vs. 10, P<0.01) in a review of 10,433 patients of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample.34 Older patients were also less likely to receive chemotherapy than younger patients. Although it is difficult to pinpoint definitive reasons for the findings in only those Stage III patients over 60 years, this may again reflect a statistical anomaly, or more likely a combination of tumor biology along with adherence to oncological principles at time of operation, as well as pathological techniques.

We acknowledge several limitations of the present study. Large population-based data sources such as SEER allow examination of nationwide trends and outcomes, providing insight into how groups represented in smaller, more controlled studies compare to the general population. However, as a clinical administrative database that relies on coding for accuracy, SEER itself is subject to coding discrepancies. However, the large sample size provided by the SEER database increases the likelihood of an even distribution of coding errors or adjuvant therapy differences amongst the various groupings. Other limitations of the present study include the mere nature of an observational, retrospective study and the inherent biases associated with it. Population-based databases such as the SEER provide a large volume of information; however, they lack specifics that could add to the study—for example, why exactly was a treatment algorithm chosen, certain patient co-morbidities, and oncological adequacy of the operation including margins. In addition, small differences relating to LNY in various age groups above or below the 12 LNY benchmark may be statistically different, but there clinical impact is unknown. Yet, our goal was to identify as best as possible what was taking place on a national level with regards to the impact age has on what is becoming a national and international standard that may ultimately have a dramatic impact on health care providers in terms of determining competency. More importantly, however, we are reminded how staging accuracy remains a critically important quality metric, as recent data has demonstrated that when chemotherapy is appropriately given for Stage III patients, despite being older, it is generally well tolerated with even fewer adverse reactions than younger patients,42 and improves overall survival.43, 44 Older patients receiving chemotherapy have been reported to have similar disease specific survival as their younger counterparts.18 Yet, when the 12 LNY benchmark is not achieved, resulting in a pathological diagnosis of Stage II disease despite “inadequate sampling”, chemotherapy is less often used in the older population.41, 45 Though we can only still speculate on reasons the LNY was lower across the study period for older patients, we were able to demonstrate a continued impact on overall survival between those achieving the 12 LNY benchmark and those who were unable to do so. Additionally, this held up in both node positive and node negative disease. Finally, although AJCC Stages were controlled for in the Cox proportional Hazard Regression model in this study, additional factors that may have impacted the analysis, adjuvant therapy use and specific surgical intervention – could unfortunately not be specifically controlled for in our modeling.

CONCLUSION

We identified a negative correlation between advancing age and LNY in non-metastatic colon cancer. This multi-factorial phenomenon may be related to surgical and pathological technique, or perhaps a biological decrease in number of evaluable LNs or immunocompetence with older age. In patients with advanced age, lower LNY was associated with decreased OS for both node-positive and node-negative CC. Based on this, the prognostic significance of the 12 LN minimum criterion should be applied even to elderly CC patients. Every attempt to adhere to proper oncological principles to attain this 12 LN minimum benchmark should be a goal at time of CC resection for all patients regardless of age in order that appropriate treatments can be considered and survival optimized even if tumor biology limits eventual outcomes.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge Tiffany Felix for her invaluable assistance supported in part by the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine. We are grateful to the members and staff of the United States Military Cancer Institute for their consistent support of this collaborative research effort.

This clinical research effort was supported, in part, by the United States Military Cancer Institute and NIH grant 2RO1CA090848.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Western Surgical Association 118th Scientific Session, Chicago, IL, November 2010.

Disclosure Information: Nothing to disclose.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: SS, AB, AS

Acquisition of data: SC

Analysis and interpretation of data: SC, SS, KZ, AS

Drafting of manuscript: SC, SS, AS, AB

Critical revision: AS, SS, AB, GP, AN, SC

Statistical expertise: SC, KZ, AS

Obtaining funding: AB, AS

Supervision: AB, AS

REFERENCES

- 1.American Cancer Society Colon Cancer Statistics. [Accessed 9/20/2010]; Available at http://www5.cancer.org/downloads/STT/Cancer_Facts_and_Figures_2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baddi L, Benson A., III Adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer: current approaches. The Oncologist. 2005;10:325–331. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-5-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson AB, 3rd, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(16):3408–3419. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibakita M, Yoshimura H, Tachibana M, Ueda S, Nagasue N. Body mass index influences long-term outcome in patients with colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57(97):62–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rajput A, Romanus D, Wieser MR, et al. Meeting the 12 lymph node (LN) benchmark in colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102(1):3–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.21532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakub JW, Russell G, Tillman CL, Lariscy C. Colon cancer and low lymph node count: who is to blame? Arch Surg. 2009;144(12):1115–1120. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider EC, Epstein AM, Malin JL, et al. Developing a system to assess the quality of care: ASCOs National Initiative on Cancer Care Quality. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Quality Forum Endorses Consense Standards for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast and Colorectal Cancer: National Qaulity Forum. first posted April 12 2007, Web based Press Release Available at http:www.facs.org/cancer/qualitymeasures.html.

- 9.Compton CC, Greene FL. The staging of colorectal cancer: 2004 and beyond. Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:295. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobin LH, Greene FL. TNM classification: clarification of number of regional lymph nodes for pN0. Cancer. 2001;92:452. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010715)92:2<452::aid-cncr1342>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen SL, Bilchik AJ. More extensive nodal dissection improves survival for stages I to III of colon cancer: a population-based study. Ann Surg. 2006;244(4):602–610. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000237655.11717.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elferink MA, Siesling S, Visser O, et al. Large variation between hospitals and pathology laboratories in lymph node evaluation in colon cancer and its impact on survival, a nationwide population-based study in The Netherlands. Ann Oncol. 2010 Jul 1; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq312. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elferink MA, Siesling S, Lemmens VE, et al. Variation in lymph node evaluation in rectal cancer: a Dutch nationwise population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Aug 24; doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1269-8. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong SL, Ji H, Hollenbeck BK, Morris AM, Baser O, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital lymph node examination rates and survival after resection for colon cancer. JAMA. 2007;298(18):2149–2154. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang GJ, Rodriguez-Bias MA, Skibber JM, Moyer VA. Lymph node evaluation and survival after curative resection of colon cancer: systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(6):433–441. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stocchi L, Fazio VW, Lavery I, Hammel J. Individual surgeon, pathologist, and other factors affecting lymph node harvest in stage II colon carcinoma. Is a minimum of 12 examined lymph nodes sufficient? Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Sep 14; doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1308-5. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fang W, Fan B, Xiong B. Analysis of pathological risk factors for lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(92–92):663–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quah HM, Joseph R, Schrag D, et al. Young age influences treatment but not outcome of colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(10):2759–2765. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9465-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajput A, Skibber J, Engstrom P, et al. NCCN Colon/Rectal Project. Meeting the 12 lymph node benchmark in colorectal cancer surgery: a comparison of NCCN and SEER data. J Clin Oncol. 2007;24(18S):4015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee S, Hofmann LJ, Davis KG, Waddell BE. Lymph node evaluation of colon cancer and its association with improved staging and survival in the Department of Defense Health Care System. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16(11):3080–3086. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0620-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.LeVoyer TE, Sigurdson ER, Hanlon AL, et al. Colon cancer survival is associated with increasing number of lymph nodes analyzed: a secondary survey of intergroup trial INT-0089. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(15):2912–2919. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore J, Hyman N, Callas P, Littenberg B. Staging error does not explain the relationship between the number of lymph nodes in a colon cancer specimen and survival. Surgery. 2010;147(3):358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang J, Kulaylat M, Rockette H, Rajput A, Dunn KB, Dayton M. Should total number of lymph nodes be used as a quality of care measure for stage III colon cancer? Ann Surg. 2009;249(4):559–563. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318197f2c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tekkis PP, Smith JJ, Heriot AG, Darzi AW, Thompson MR, Stamatakis JD. Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. A national study on lymph node retrieval in resectional surgery for colorectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(100):1673–1683. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0691-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw A, Collins EE, Fakis A, Patel P, Semeraro D, Lund JN. Colorectal surgeons and biomedical scientists improve lymph node harvest in colorectal cancer. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12(4):295–298. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0438-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norwood MG, Sutton AJ, West K, Sharper DP, Hemingway D, Kelly MJ. Lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer resection specimens: national standards are achievable, and low numbers are associated with reduced survival. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(4):304–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogino S, Nosho K, Irahara N, et al. Negative lymph node count is associated with survival of colorectal cancer patients, independent of tumoral molecular alterations and lymphocytic reaction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(2):420–433. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swanson RS, Compton CC, Stewart AK, Bland KI. The prognosis of T3N0 colon cancer is dependent on the number of lymph nodes examined. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(1):65–71. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rieger NA, Barnett FS, Moore JW, et al. Quantity of pathology reporting impacts on lymph node yield in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(4):463. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ostadi MA, Harnish JL, Stegienko S, Urbach DR. Factors affecting the number of lymph nodes retrieved in colorectal cancer specimens. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(12):2142–2146. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemmens VE, van Lijnschoten I, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Rutten HJ, Verheij CD, Coebergh J-WW. Pathology practice patterns affect lymph node evaluation and outcome of colon cancer: a population based study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(12):1803–1809. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bilimoria KY, Palis B, Stewart AK, et al. Impact of tumor location on nodal evaluation for colon cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(2):154–161. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-9114-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bilimoria KY, Steward AK, Palis BE, Bentrem DJ, Talamonti MD, Ko CY. Adequacy and importance of lymph node evaluation for colon cancer in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206(2):247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardiman KM, Cone M, Sheppard BC, Herzig DO. Disparities in the treatment of colon cancer in octogenarians. Am J Surg. 2009;197(5):624–628. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou JF, Row D, Gonen M, Liu YH, Schrag D, Weiser MR. Clinical and pathologic factors that predict lymph node yield from surgical specimens in colorectal cancer: a population-based study. Cancer. 2010;116(11):2560–2570. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baxter NN, Virnig DJ, Rothenberger DA, Morris AM, Jessurun J, Virnig BA. Lymph node evaluation in colorectal cancer patients: a population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(3):219–225. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsikitis VL, Larson DL, Wolff BG, et al. Survival in stage III colon cancer is independent of the total number of lymph nodes retrieved. J AM Coll Surg. 2009;208(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takano S, Kato J, Yamamoto H, et al. Identification of risk factors for lymph node metastasis of colorectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(75):746–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen SL, Steele SR, Eberhardt J, Zhu K, Bilchik A, Stojadinovic A. Lymph Node Ratio as a Quality and Prognostic Indicator in Stage III Colon Cancer. Ann Surg. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ffa780. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans MD, Barton K, Rees A, Stamatakis JD, Karandikar SS. The impact of surgeon and pathologist on lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer and its impact on survival for patients with Duke’s stage B disease. Colorectal Dis. 2008;10(20):157–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Earle CC, Weiser MR, Ter Veer A, et al. Effect of lymph node retrieval rates on the utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy in stage II colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:525–528. doi: 10.1002/jso.21373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kahn KL, Adams JL, Weeks JC, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy use and adverse events among older patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA. 2010;303(11):1037–1045. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sundararajan V, Mitra N, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Heitjan DF, Neugut AI. Survival associated with 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy among elderly patients with node-positive colon cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):349–357. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuckerman IH, Rapp T, Onukwugha E, Davidoff A, Choti MA. Effect of age on survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy in elderly patients with Stage III colon cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1403–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schrag D, Cramer LD, Bach PB, Begg CB. Age and adjuvant chemotherapy use after surgery for stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(11):850–857. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.11.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]