Abstract

The S5 locus regulates spikelet fertility of indica/japonica hybrid rice (Oryza sativa). There are three alleles at the S5 locus, including an indica allele (S5i), a japonica allele (S5j), and a wide-compatibility allele (S5n). This study analyzed the molecular basis for S5-dependent reproductive isolation and compatibility of indica/japonica rice hybrids. Three S5 alleles were expressed at extremely low levels, and only in the ovary. S5n was more similar to S5i in both RNA and protein expression profiles. The S5 locus was not essential for embryo sac development, although deleterious interactions between S5i and S5j resulted in reduced rates of spikelet fertility. The yeast two-hybrid system was used to test direct interactions between S5-encoded proteins. The results indicated that the S5i- and S5j-encoded eukaryotic aspartyl proteases formed both homodimers and heterodimers, whereas the S5n-encoded aspartyl protease was incapable of dimerization. Site-directed mutagenesis revealed that a single amino acid difference between S5i- and S5j-encoded aspartyl proteases (phenylalanine/leucine at residue 273) was primarily responsible for embryo sac abortion. The S5 locus may have promoted the subspeciation of indica and japonica, but it also enables gene flow between them.

Low spikelet fertility is one of the major obstacles to breeding super indica/japonica rice (Oryza sativa) hybrids (Kato et al., 1928; Liu et al., 1996). A unique group of rice germplasm, termed wide-compatibility varieties (WCVs), has enabled more effective use of intersubspecific heterosis (Ikehashi and Araki, 1986). WCVs can overcome reproductive barriers and produce fertile hybrids when crossed to indica or japonica subspecies. To explain this phenomenon, Ikehashi and Araki (1986) proposed a “one-locus spore-gametophytic interaction” genetic model (i.e. the S5 locus is responsible for the fertility of intersubspecific hybrids), and one of three alleles, namely S5i, S5j, and S5n, is present in indica, japonica, and WCVs, respectively. The S5n allele is denoted the wide-compatibility gene because full fertility is observed in both S5iS5n and S5jS5n genotypes.

The fertility of intersubspecific hybrid rice is a very complex trait that is influenced by multiple genetic factors and environmental conditions. More than 50 loci across the rice genome have been shown to affect hybrid sterility. Of these loci, approximately 20 control female gamete abortion, more than 30 are involved in male gamete abortion, and over 10 affect spikelet sterility (Ouyang et al., 2009). In many cases, fertility-related loci genetically interact with one another, increasing the complexity of this phenotype. The S5 locus, however, plays a particularly important role in embryo sac sterility, and S5n from a WCV can greatly enhance embryo sac fertility (Ikehashi and Araki, 1986; Liu et al., 1992, 1997; Yanagihara et al., 1995; Wang et al., 1998, 2005; Yan et al., 2000; Liang et al., 2001; Yi et al., 2001). It is critical, therefore, to understand the genetic mechanisms that underlie S5-dependent fertility of intersubspecific rice hybrids.

Significant progress has been made recently toward characterizing the S5 locus. Ji et al. (2005) mapped S5n to a 50-kb region based on multiple near-isogenic lines. Qiu et al. (2005) then mapped the wide-compatibility gene to a 40-kb interval. These two regions have in common approximately 25 kb of sequence that is predicted to contain two genes. The first gene is Asp, which encodes a eukaryotic aspartyl protease (AP), whereas the second gene encodes a hypothetical protein. To distinguish between these two candidate genes, a different version of the S5 locus, which was derived from the indica rice cv Nanjing11, was introduced into the japonica rice cv Balilla. Reduced levels of spikelet fertility were observed in transgenic T0 and T1 plants that contained the exogenous Asp gene. This provides strong evidence that Asp is the critical component within the S5 locus (Chen et al., 2008; Ji et al., 2010). Ji et al. (2010) further revealed that two S5 sequence alterations were associated with spikelet fertility of the indica/japonica hybrid. A 136-bp deletion within the S5 locus, which affects the N terminus of AP, results in the wide-compatibility S5n gene. In addition, a heterozygous C/A site within Asp causes partial sterility of indica/japonica hybrids (Ji et al., 2010). A triallelic system has been proposed to explain reproductive isolation and compatibility between indica and japonica subspecies (Chen et al., 2008). In this system, S5i and S5j represent two noncompatible alleles, which have promoted indica/japonica differentiation. In contrast, S5n is a neutral allele and produces fertile offspring in combination with either S5i or S5j. S5n contributes, therefore, to gene flow between indica and japonica (Chen et al., 2008). Analysis of the Sa locus, which controls male sterility of indica/japonica hybrids (Long et al., 2008), revealed a similar triallelic system, suggesting that such systems are widespread within rice (Ouyang et al., 2010).

Here, we dissected the molecular basis of the S5-triallelic system by identifying functional differences between S5 alleles and characterizing their genetic interactions. Our results have deepened current understanding of the mechanisms underlying reproductive isolation and compatibility between intersubspecific rice hybrids.

RESULTS

Deleterious Genetic Interactions Account for the Reduced Fertility of Rice Hybrids

Spikelet fertility was investigated for six S5 genotypes (S5iS5i, S5jS5j, S5nS5n, S5iS5j, S5jS5n, and S5iS5n) within three genetic backgrounds (Nanjing11 [indica], Balilla [japonica], and their hybrid Nanjing11/Balilla [indica/japonica]). The results revealed that various genetic elements presented and affected spikelet fertility, including genetic background effects, allelic interactions, and the interactions between the S5 locus and genetic backgrounds (Table I). S5iS5i-Nanjing11 and S5jS5j-Balilla are normal indica and japonica cultivars and, therefore, had high spikelet fertility in both 2008 and 2009. S5iS5n-Nanjing11 and S5nS5n-Nanjing11 also had high spikelet fertility levels and were indistinguishable from S5iS5i-Nanjing11 in this regard. Similarly, the spikelet fertilities of S5jS5j-Balilla, S5jS5n-Balilla, and S5nS5n-Balilla were essentially equivalent. This implied that S5n did not negatively impact spikelet fertility when introduced into the indica or japonica background. This conclusion was further supported when the S5nS5n genotype resulted in the highest spikelet fertility within the Nanjing11/Balilla genetic background.

Table I.

Spikelet fertility of various S5 genotypes within the Nanjing11 (indica), Balilla (japonica), and Nanjing11/Balilla (indica/japonica) genetic backgrounds

| Genotype at the S5 Locus | Spikelet Fertility |

||

| Nanjing11 | Balilla | Nanjing11/Balilla | |

| % (mean ± sd) | |||

| S5iS5i | 93.81 ± 1.91a | 84.13 ± 4.26 | 86.20 ± 2.35 |

| 94.03 ± 0.96b | 83.77 ± 4.98 | 82.72 ± 5.08 | |

| S5jS5j | /c | 84.55 ± 4.12 | / |

| / | 94.69 ± 1.66 | / | |

| S5nS5n | 91.48 ± 1.26 | 89.97 ± 1.06 | 89.11 ± 4.16 |

| 92.79 ± 1.24 | 86.59 ± 6.51 | 87.56 ± 1.58 | |

| S5iS5j | / | 61.62 ± 8.91 | 32.13 ± 0.15 |

| / | 67.48 ± 2.12 | 30.92 ± 4.81 | |

| S5iS5n | 92.17 ± 3.91 | 82.34 ± 1.26 | 87.26 ± 1.51 |

| 91.28 ± 0.89 | 78.52 ± 3.17 | 86.67 ± 1.93 | |

| S5jS5n | / | 87.13 ± 3.12 | 70.91 ± 0.56 |

| / | 91.42 ± 1.08 | 67.35 ± 2.71 | |

Data in the first row indicate spikelet fertilities in 2008.

Data in the second row indicate spikelet fertilities in 2009.

/, Data not available.

In other genetic contexts, however, these same S5 genotypes resulted in large differences in spikelet fertility. For the S5iS5i genotype, the fertility of S5iS5i-Nanjing11 was higher than S5iS5i-Balilla and S5iS5i-Nanjing11/Balilla. The same result was seen for the S5iS5n genotype, as S5iS5n-Nanjing11 fertility was elevated compared with both S5iS5n-Balilla and S5iS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla. An interaction between S5i and the japonica background, therefore, reduced spikelet fertility by approximately 10% in both 2008 and 2009. Similar comparisons between S5jS5j-Balilla and S5jS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla indicated an interaction between S5j and the indica background that reduced spikelet fertility by approximately 20%. When S5i and S5j were present in the same genetic background, however, a dramatic reduction in spikelet fertility was observed. For S5iS5j-Balilla, spikelet fertilities were 62% and 67% in 2008 and 2009, respectively. These represent much lower fertilities than seen with other S5 genotypes within the Balilla genetic background. In this case, except for the S5i-japonica interaction, the S5i/S5j allelic interaction was another genetic factor that lowered fertility. Because S5n and S5j had similar effects on spikelet fertility in the japonica background, the difference in fertility between S5iS5n-Balilla and S5iS5j-Balilla reflected an S5i/S5j allelic interaction. On average, the S5i/S5j allelic interaction reduced spikelet fertility by approximately 16% within the japonica background. The most dramatic reduction in spikelet fertility occurred in S5iS5j-Nanjing11/Balilla, a typical intersubspecific rice hybrid. Spikelet fertilities for these plants were consistently low (32% and 31% in 2008 and 2009, respectively). In these crosses, therefore, poor spikelet fertility resulted from genetic interactions between S5i and japonica, S5j and indica, and S5i and S5j. Because S5n did not affect spikelet fertility in this context, it is likely that fertility differences between S5nS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla and S5jS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla represent the S5j-indica genetic effect within the indica/japonica background. Spikelet fertility effects that were specific for the S5i/S5j allelic interaction were estimated, therefore, by subtracting the S5i-japonica and S5j-indica genetic effects from the S5nS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla fertility. The results showed that the S5i/S5j allelic interaction could reduce spikelet fertility by approximately 36% in the Nanjing11/Balilla (indica/japonica) genetic background.

Expression Profiles of S5 Alleles in Both Homozygous and Heterozygous Genotypes

In immature leaves and roots of Nanjing11 (indica), Balilla (japonica), and 02428 (WCV) plants, expression of the three S5 alleles was undetectable. In spikelet tissue, however, S5 alleles were expressed at each of the four developmental stages (1–4) that were analyzed. Compared with actin, however, S5 expression levels were extremely low (Fig. 1). S5i and S5n had similar patterns of expression, with relatively constant levels of expression during stages 1, 2, and 3 but a little higher expression at stage 4 (Fig. 1). In contrast, expression levels of S5j were relatively high during stages 1 to 3 but decreased at stage 4 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Expression levels of three S5 alleles in spikelet tissue. RNA expression levels were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Samples were collected from 02428 (S5n), Nanjing11 (S5i), and Balilla (S5j) plants at four developmental stages: (1) panicle extension stage (panicle 5–10 cm in length), (2) booting stage (panicle 10–20 cm in length), (3) heading stage (panicle more than 20 cm in length), and (4) full bloom stage. The actin gene was used as an internal control. Error bars represent sd from three independent replicates. * Significant difference observed when compared with the previous stage for the same genotype (P < 0.05).

For heterozygous genotypes, S5iS5j dramatically decreased spikelet fertility, whereas S5iS5n and S5jS5n exhibited wide compatibility. Therefore, we sought to characterize the expression level of each S5 allele in the heterozygous context. By crossing Balilla with Nanjing11 and S5nS5n-Nanjing11, we generated two genotypes: S5iS5j-Nanjing11/Balilla and S5jS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla. In the S5j allele, the MseI restriction sequence (TTAA) is found at the first single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP; C/A) site (Supplemental Fig. S1). This sequence is not present in S5i or S5n (TTCA; Ji et al., 2010). As such, reverse transcription (RT)-PCR products derived from the S5j allele can be cleaved by MseI, whereas products derived from S5i or S5n remain uncut. For the S5iS5j genotype, the two S5 alleles had complementary patterns of expression. S5j expression was highest at stage 1 and gradually diminished during subsequent developmental stages. In contrast, S5i expression gradually increased during development, reaching a maximal value at stage 4 (Fig. 2A). These patterns are quite consistent with those observed for the parental lines Nanjing11 (S5i) and Balilla (S5j). The situation was quite different, however, for the S5jS5n genotype. S5j expression was highest at stage 1 (as seen before) but relatively low during stages 2 to 4. Throughout the developmental time course, S5n expression was reduced compared with S5j and was very low at stage 1 (Fig. 2B). Consistent with allelic expression patterns seen in parental strains (Fig. 1), the pattern of S5n expression was more similar to S5i than S5j. As S5i and S5n both lack the MseI site at the SNP (C/A) site, it was not possible to determine the differential allelic expression patterns for the S5i/S5n genotype.

Figure 2.

Differential expression of three S5 alleles. After digestion with MseI, the RT-PCR product from the S5j allele is cleaved into two fragments (506 and 200 bp). In contrast, MseI does not cleave PCR products from the S5n and S5i alleles. Digested S5 PCR products (top), undigested S5 PCR products (middle), and actin control products (bottom) are shown in each lane. Results from S5iS5j-Nanjing11/Balilla (A) and S5jS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla (B) are shown. Lanes 1 to 4 contain spikelet samples that were collected from developmental stages 1 to 4, respectively. Lanes 5 and 6 contain spikelet samples from parental lines. Parental lines include S5j/S5j-Balilla and S5i/S5i-Nanjing11 (A) and S5j/S5j-Balilla and S5n/S5n-Nanjing11 (B).

Expression and Tissue Localization Analysis of APs

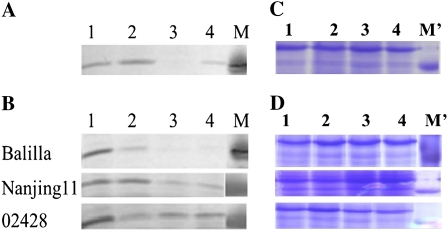

APs encoded by the three S5 alleles were analyzed by western blotting. The most dramatic difference among these proteins was associated with an approximately 24-kD isoform of AP (Fig. 3), which corresponds to the lytic AP product. At stage 4, there were distinct 24-kD isoforms of AP in samples derived from Nanjing11 and two WCVs (02428 and Dular). For Balilla samples, however, only faint 24-kD bands were detected (Fig. 3A). We extended our analysis by comparing spikelet samples among Balilla, Nanjing11, and 02428 from stages 1 to 4. For all three rice cultivars, the highest levels of the 24-kD band were associated with stage 1; this band gradually weakened as spikelet development proceeded. During stages 2 to 4, the 24-kD band associated with Balilla was weaker than that of Nanjing11 or 02428. For Balilla, in fact, the 24-kD band was nearly undetectable at stages 3 and 4 (Fig. 3B). As was seen for the allelic expression data, AP protein analyses suggested that Nanjing11 and 02428 are quite similar to one another, whereas Balilla is different.

Figure 3.

AP levels associated with the S5n, S5i, and S5j alleles. A, Levels of AP (the lytic AP product) in spikelets collected from developmental stage 4. Samples from 02428 (S5n; lane 1), Dular (S5n; lane 2), Balilla (S5j; lane 3), and Nanjing11 (S5i; lane 4) are shown. B, Lanes 1 to 4 contain spikelet samples that were collected from developmental stages 1 to 4, respectively. Sample types are indicated to the left. Lane M shows the 24-kD protein marker. C, Gel image of an equal volume of protein samples for blotting in A. The proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue. D, Gel image of an equal volume of protein samples for blotting in B. The proteins were separated via SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

To examine the tissue localization of AP, we constructed two expression vectors in which S5j and S5n coding sequences were fused in frame with the GFP coding sequence (pAj-GFP and pAn-GFP, respectively). Tissues from pAj-GFP and pAn-GFP transgenic plants were harvested at different developmental stages. S5-encoded APs were only found in ovaries before and during flowering (Supplemental Fig. S2), which strongly suggested that AP functions to regulate embryo sac abortion.

S5-Allele Knockdown Does Not Impair Spikelet Fertility

A 136-bp sequence (present in S5i and S5j but absent from S5n) was used as a target for RNA interference (RNAi). This sequence encodes the N-terminal signal peptide of AP. Using S5jS5j-Balilla as the receptor, RNAi transgenic lines had spikelet fertilities that were indistinguishable from those of blank vector controls. This analysis was performed at the T0 generation under two environmental conditions. Similar results were seen when using either S5iS5i-Balilla or S5nS5n-Balilla as the rice receptor (Table II). To confirm this result, RNAi transgenic lines were selfed to produce the T1 generation. Regardless of the genetic background, spikelet fertilities of T1 transgenic and control plants were again indistinguishable (Table II).

Table II.

Pairwise comparison of spikelet fertility between transgenic plants expressing the RNAi vector and negative controls

| Generation | Receptora | Average Fertility |

Fertility Difference | Pd | |

| Transgenicb | Controlc | ||||

| % | |||||

| T0 | S5jS5j-Balilla (1) | 86.64 | 87.93 | −1.29 | 0.5940 |

| S5jS5j-Balilla (2) | 92.99 | 96.66 | −3.67 | 0.3458 | |

| S5iS5i-Balilla (1) | 86.70 | 86.71 | −0.01 | 0.9993 | |

| S5iS5i-Balilla (2) | 93.51 | 86.98 | 6.52 | 0.2406 | |

| S5nS5n-Balilla | 91.19 | 95.04 | −3.85 | 0.7189 | |

| T1 | S5jS5j-Balilla | 80.10 | 81.92 | −1.81 | 0.4471 |

| S5iS5i-Balilla | 87.19 | 87.97 | −0.78 | 0.4813 | |

| S5nS5n-Balilla | 81.80 | 88.77 | −6.98 | 0.3380 | |

| Wuxiangjing | 88.11 | 89.26 | −1.15 | 0.4599 | |

(1) and (2) denote two environmental conditions in which spikelet fertility was tested.

Transgenic plants (i.e. transformed with the RNAi vector).

Control plants that did not contain the RNAi vector.

Significant difference in spikelet fertility between transgenic and control plants (P < 0.05). In the T0 generation, plants transformed with a blank vector served as the negative control, whereas in the T1 generation, nontransgenic plants were used as the negative control.

To determine whether this RNAi strategy effectively reduced S5 expression, we used RT-PCR analysis. In nontransgenic S5iS5i-Balilla spikelets (T1), S5i expression gradually increased from stages 2 to 4. In T1 S5iS5i-Balilla that carried the RNAi transgene, however, the expression of S5i was reduced at each developmental stage. This effect was particularly pronounced at stage 4, when S5i expression was barely detectable (Fig. 4A). Similar RT-PCR results were obtained for S5j when Wuxiangjing was used as the receptor (Fig. 4B). In addition, we checked S5n expression in both transgenic and nontransgenic S5nS5n-Balilla (T1) and observed no expression level changes. This was predicted, as the RNAi transgene did not target the S5n sequence. To our surprise, however, reduced expression of S5i or S5j (via RNAi) did not affect embryo sac development. Spikelet fertilities of transgenic and nontransgenic plants (T1) were essentially equivalent (Table II).

Figure 4.

RNAi-induced knockdown of S5 alleles. RNAi vectors were separately introduced into S5iS5i-Balilla (A) and S5jS5j-Wuxiangjing (B). Light gray bars indicate transgenic T1 plants, and dark gray bars indicate nontransgenic T1 plants. Spikelet tissues were collected from developmental stages 2 to 4. S5 expression was lower in transgenic T1 plants compared with nontransgenic plants at every developmental stage tested. The ΔΔΔΔCT value was used to obtain the amount of transcripts of one S5 allele relative to the most abundant S5 allele (S5h). ΔΔΔΔCT = (CTS5−CTActin)−(CTS5h−CTActin). The ΔΔΔΔCT value was converted to the linear form in terms of 2−ΔΔΔΔCT for statistical analysis. Error bars represent sd from three independent replicates.

Interactions among APs

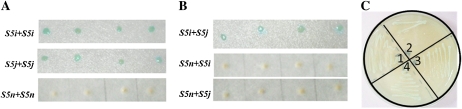

In the indica/japonica rice hybrid, the presence of both S5i and S5j alleles dramatically reduced spikelet fertility. This genetic interaction suggested that these two versions of AP may physically interact (i.e. form a dimer). The yeast two-hybrid system was used, therefore, to detect interactions among S5-encoded APs. As an initial control (the transcriptional activation test), we confirmed that S5 bait proteins were unable to activate reporter gene expression. When S5i-encoded AP was used as both bait and prey, a protein-protein interaction was detected (i.e. the yeast colonies turned blue after color development). A similar result was seen with S5j-encoded AP, whereas the S5n-encoded AP was not able to dimerize (Fig. 5A). In addition, interactions between S5i- and S5j-encoded APs were detected. S5n-encoded AP, however, was unable to interact with either the S5i- or S5j-encoded AP (Fig. 5B). For each experiment, similar results were obtained when the bait and prey were switched. And the interaction was further confirmed by the growth of positive yeast clones on selective medium (Fig. 5C). These findings implied that S5-encoded APs (the S5i- and S5j-encoded versions) may physically interact in plant cells to form homodimers or heterodimers (depending on the genetic context). For the S5n-encoded AP, however, the lack of the first 115 N-terminal amino acids (Ji et al., 2010) may prevent the formation of an AP dimer.

Figure 5.

Protein-protein interactions between S5-encoded APs. A and B, The yeast two-hybrid system was used to detect interactions between S5-encoded APs. Both homophilic (A) and heterophilic (B) interactions were investigated. Yeast clones with a blue color indicate an interaction, whereas white clones denote the lack of an interaction. C, Yeast clones containing interacting baits and preys can grow well on selective medium yeast nitrogen base(Gal)-Ura-His-Trp-Leu. Sector 1, S5i + S5i; sector 2, S5i + S5j; sector 3, S5j + S5j; sector 4, positive control.

The C/A SNP Site within the S5 Locus Is the Key Determinant of Spikelet Fertility

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to generate two artificial S5 genes. For S5-T, an A-T substitution was introduced in the 1,010-bp SNP site of S5j (Ji et al., 2010), forming the TTT codon (Phe). S5-G was constructed in a similar manner, introducing an A-G substitution at the same site to form the TTG codon (Leu; Supplemental Fig. S3). These two artificial S5 genes were transformed into Balilla, and positive T0 plants were selfed to generate the T1 generation. In the T1 generation, transgenic plants containing the S5-T gene reduced spikelet fertilities by approximately 13% on average, and seven of 11 independent transformation events showed significantly lower spikelet fertilities in transgenic plants than nontransgenic controls (Table III). In contrast, S5-G slightly reduced spikelet fertility by approximately 5% on average, and only three independent transformation events showed significantly lower spikelet fertilities (Table III). For the SNP site located at residue 273, S5-T encoded for Phe (the same as S5i) and S5-G encoded for Leu (the same as S5j). Apart from position 273, S5-T and S5-G encoded amino acid sequences that were identical to S5j, including Val at position 471 (Chen et al., 2009). As a result, transgenic plants that contained the exogenous S5-T gene had an S5jS5j+S5-T genotype, which is essentially equivalent to S5jS5j+S5i. Similarly, plants with exogenous S5-G had an S5jS5j+S5-G genotype (i.e. S5jS5j+S5j). As S5-T reduced spikelet fertility, the negative interaction between S5i and S5j could thus be explained by the amino acid difference at position 273 within AP. The expression of AP-Phe-273 and AP-Leu-273 dramatically reduced spikelet fertility, especially in the indica/japonica background.

Table III. Pairwise comparison of spikelet fertility between T1 plants transformed with site-directed mutant constructs and nontransgenic controls.

Significant differences in spikelet fertility between transgenic and nontransgenic plants within the T1 generation are indicated at P < 0.05 (*) and P < 0.01 (**).

| Construct | Transformation Event | Average Fertility |

Fertility Difference | P | |

| Transgenic | Nontransgenic | ||||

| % | |||||

| pAsp-T | C9562 | 77.01 | 91.48 | −14.47 | 0.0148* |

| C9564 | 62.53 | 92.18 | −29.65 | 0.0234* | |

| C9571 | 79.74 | 92.11 | −12.38 | 0.0157* | |

| C9574 | 83.60 | 90.80 | −7.20 | 0.0213* | |

| C9576 | 78.40 | 87.23 | −8.83 | 0.0770 | |

| C9579 | 83.43 | 91.14 | −7.72 | 0.1173 | |

| C9588 | 84.63 | 94.79 | −10.16 | 0.0000** | |

| C9596 | 69.11 | 87.94 | −18.83 | 0.0113* | |

| C9607 | 71.38 | 88.40 | −17.02 | 0.0331* | |

| C9608 | 82.41 | 88.08 | −5.68 | 0.1393 | |

| C9610 | 75.94 | 81.87 | −5.93 | 0.1475 | |

| Average | 77.11 | 89.64 | −12.53 | ||

| pAsp-G | C9621 | 76.79 | 85.22 | −8.42 | 0.0998 |

| C9623 | 82.14 | 82.55 | −0.41 | 0.4681 | |

| C9626 | 80.41 | 81.45 | −1.04 | 0.4046 | |

| C9628 | 80.61 | 88.50 | −7.88 | 0.1842 | |

| C9632 | 82.49 | 79.00 | 3.50 | 0.2748 | |

| C9633 | 81.94 | 78.08 | 3.86 | 0.2262 | |

| C9637 | 75.20 | 84.33 | −9.13 | 0.1203 | |

| C9640 | 76.09 | 82.58 | −6.49 | 0.0972 | |

| C9641 | 82.42 | 87.37 | −4.96 | 0.1547 | |

| C9643 | 75.71 | 87.86 | −12.15 | 0.0954 | |

| C9646 | 81.38 | 90.37 | −8.99 | 0.0198* | |

| C9648 | 85.60 | 92.40 | −6.80 | 0.0268* | |

| C9650 | 82.05 | 90.01 | −7.96 | 0.0194* | |

| C9653 | 83.57 | 86.87 | −3.30 | 0.2906 | |

| C9663 | 82.99 | 90.34 | −7.35 | 0.1436 | |

| Average | 80.63 | 85.80 | −5.17 | ||

DISCUSSION

S5n Is More Similar to S5i Than S5j

Compared with S5i and S5j, the S5n allele contains a 136-bp deletion, which eliminates residues at the N-terminal region of AP. S5i and S5j differ at three sites: two SNPs within the coding region (located 1,010 bp [C/A] and 1,604 bp [C/T] downstream of the start codon) and a 1-bp insertion/deletion within the 5′ untranslated region (Chen et al., 2008). Despite the 136-bp deletion, results concerning S5n were similar to those for S5i, including the RNA expression profile, differential allelic expression, and western-blot data (Figs. 1–3). Residue Phe-273 of AP is highly conserved among species, whereas the Leu-273 variant is encoded only by S5j (Chen et al., 2009). Based on these findings, we speculate that it is the C/A SNP, rather than the 136-bp insertion/deletion, that regulates the expression of the S5 locus. Among the three S5 alleles, S5i is believed to be the most ancient, independently evolving into S5j and S5n via neutral mutation (Ouyang et al., 2010). This evolutionary pathway can be reconciled based on the monophyletic origin of rice, in which indica originated from common wild rice whereas japonica was derived from indica during adaptation to areas of high elevation and latitude (Ding, 1957; Chang, 1976; Oka, 1988; Lu et al., 2002).

S5 Knockdown Does Not Impair Embryo Sac Development

The wide-compatibility gene S5n has long been considered the central force for overcoming fertility barriers associated with the indica/japonica rice hybrid. Attempts have been made, therefore, to use S5n to breed super intersubspecific rice hybrids. Once S5n was cloned and characterized, however, Chen et al. (2008) suspected that S5n was a loss-of-function allele. The S5n-encoded AP lacks a signal sequence and thus does not localize to the appropriate cellular compartment. In addition, S5n has been introduced into Balilla (driven by the native or cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter), and the resulting plants have been crossed to Nanjing11. No increase in spikelet fertility has been observed, however, in transgenic Nanjing11/Balilla hybrids, which suggests that S5n is a nonfunctional allele (Ji et al., 2010). Compared with S5n, both S5i- and S5j-encoded APs have an N-terminal signal peptide and predominantly localize to the cell wall (Chen et al., 2008). In this study, an RNAi construct was made that specifically targeted S5i and S5j. The RNAi target sequence was a 136-bp region that is absent from S5n. The expression levels of both S5i and S5j are much lower than that of the Actin gene (Fig. 1), and RNAi-mediated interference further brought the S5 expression to an even lower level in the transgenic plants (Fig. 4). This, however, did not affect spikelet fertility (Table II). This finding suggests that S5 alleles either do not directly regulate embryo sac development or function well at variable expression levels, even at a very low expression level.

Formation of an AP Heterodimer Is Key to Reproductive Isolation

The formation of an AP dimer has been reported in species other than rice, including the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) CDR1 protein (Simões et al., 2007). Bioinformatics analyses of S5-encoded APs suggest that these proteins may form dimers. Bomblies (2010) hypothesized that S5-encoded APs normally function as homodimers and that intersubspecific heterodimers may lead to aberrant protein activity and gamete abortion. Our yeast two-hybrid data support this hypothesis (Fig. 5). The S5i- and S5j-encoded APs formed both homodimers and heterodimers, whereas the S5n-encoded AP did not dimerize. These findings support a role for these three S5 alleles in reproductive isolation and compatibility. The S5n-encoded AP likely failed to dimerize because of its N-terminal deletion and, as a result, did not impair spikelet fertility. For example, S5nS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla had normal levels of spikelet fertility, whereas S5i and S5j effectively blocked gene flow by reducing spikelet fertility within japonica and indica genetic backgrounds, respectively. This indicates detrimental interactions between S5-encoded AP homodimers and the genetic background. Moreover, the strongest genetic force that affected spikelet fertility was the interaction between S5i and S5j. This implies that AP heterodimers have aberrant activity, which inhibits embryo sac development. We conclude that the formation of an AP dimer is requisite for AP activity and that AP heterodimers lead to reduced fertility and contribute to reproductive isolation through deleterious interactions with various genetic backgrounds.

The PCS1 (for promotion of cell survival 1) gene encoding an aspartic protease in Arabidopsis was reported to be involved in programmed cell death in embryonic development and reproduction processes (Ge et al., 2005). Loss-of-function mutation of PCS1 causes excessive cell death and defects in both gametogenesis and embryogenesis. Based on a tissue localization study using pAj-GFP and pAn-GFP constructs, AP is only weakly expressed in ovary before and during flowering, but not after flowering (Supplemental Fig. S2). It is tempting to speculate that the S5-encoded AP is involved in programmed cell death in the rice ovary. The AP heterodimers may contribute to hybrid sterility by interfering with normal cell growth during gametogenesis and/or embryogenesis. Future study on the gametes and embryo cells is required to provide evidence for this hypothesis.

Position 273 Is Critical for AP Function

Phe-273 is a highly conserved residue among APs from different species, with the exception of the japonica subspecies, which contains Leu-273. In contrast, residue 471 is quite divergent among APs (Chen et al., 2009), suggesting a more important role for residue 273 in AP function. Direct evidence for this hypothesis was provided by our previous report, which demonstrated that all chimeric S5j-S5n alleles with a crossover event before the first C/A SNP (corresponding to the residue 273 site) exhibited normal spikelet fertility in combination with S5i alleles (Ji et al., 2010). In this study, we provide direct evidence for this hypothesis (Table III). The introduction of exogenous Asp-T or Asp-G into Balilla confirmed that a single amino acid substitution at residue 273 (Phe/Leu) creates an AP heterodimer that severely impairs embryo sac development.

New Insights into the Triallelic System

Based on sequence features and functions of the S5 alleles, Chen et al. (2008) proposed that the S5 locus functions as a triallelic system. Data presented in this study shed new light on the triallelic system. Beneficial interactions between the S5i-encoded AP homodimer and its indica genetic background contributed to high levels of spikelet fertility. The same conclusion can be drawn for S5j and the japonica background. In indica/WCV rice hybrids (or japonica/WCV or WCV/WCV), spikelet fertility is primarily regulated by interactions between AP and the genetic background, as S5n essentially represents a loss-of-function allele. As a result, deleterious interactions between S5i-encoded AP homodimers and the japonica genetic background slightly reduced spikelet fertility in S5iS5n hybrids when compared with normal japonica varieties. Similarly, interactions between S5j-encoded AP homodimers and the indica genetic background reduced spikelet fertility in S5jS5n hybrids. In indica/japonica rice hybrids, however, both S5i- and S5j-encoded APs were present. These likely form S5i-encoded AP homodimers, S5j-encoded AP homodimers, and AP heterodimers at a 1:1:2 ratio. Deleterious interactions between the two AP homodimers and the indica/japonica genetic background reduced spikelet fertility by approximately 30%. In addition, negative interactions between the AP heterodimer and the indica/japonica genetic background reduced spikelet fertility by an additional approximately 35%. This latter reduction can be entirely attributed to a single amino acid difference (Phe/Leu) at position 273 of AP. Deleterious interactions between AP dimers and genetic backgrounds may help to explain the reproductive barriers observed in indica/japonica rice hybrids. Based on the Bateson-Dobzhansky-Muller model, postzygotic isolation in hybrids was contributed by the deleterious interaction of genes derived from different species or populations (Dobzhansky, 1934; Muller, 1942). The S5 locus could be one of the contributors. The S5i and S5j alleles are fixed in indica and japonica rice subspecies, respectively. Once these two S5 alleles were brought together in intersubspecific hybrid rice, a deleterious interaction between them led to low fertility, so-called hybrid incompatibility. In the triallelic system, functional alleles (i.e. S5i and S5j) prevent gene flow between subspecies, which likely contributes to the maintenance of genetic isolation of indica and japonica; the presence of a null allele (i.e. S5n), however, enables genetic communication between them.

CONCLUSION

The sequence features of the S5 alleles and their genetic interactions form the basis for S5-regulated spikelet fertility. S5n was more similar to S5i than S5j with regard to the RNA and protein expression profiles. The S5 locus is probably not indispensable for embryo sac development, as S5n is a loss-of-function allele and knockdown of S5i or S5j did not impair the spikelet fertility either. Interactions between S5i- and S5j-encoded aspartyl protease would lead to the reduced fertility of the indica/japonica rice hybrid, while the failure of dimerization for the S5n-encoded aspartyl protease could explain its wide compatibility with either S5i or S5j. A single amino acid difference (Phe/Leu) at the residue 273 site between the S5i- and S5j-encoded APs was primarily responsible for embryo sac abortion. The S5 locus may have promoted subspeciation of indica and japonica, but it also enables genetic communication between them.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The indica rice (Oryza sativa) cv Nanjing11, japonica rice cv Balilla, and wide-compatibility cv 02428 were used to develop a series of lines that were nearly isogenic at the S5 locus after 10-generation backcrossings and four-generation selfings. Marker-assisted selection was also used during this process. As a consequence, the S5n allele from 02428 was integrated into the Nanjing11 and Balilla lines to generate the near-isogenic lines S5nS5n-Nanjing11 and S5nS5n-Balilla, respectively. Similarly, the S5i allele of Nanjing11 was introduced into Balilla and the S5j allele of Balilla was introduced into Nanjing11 to produce S5iS5i-Balilla and S5jS5j-Nanjing11, respectively. Pairwise crosses were established between these Nanjing11 and Balilla near-isogenic lines to place six S5 genotypes (S5iS5i, S5jS5j, S5nS5n, S5iS5n, S5jS5n, and S5iS5j) into three genetic backgrounds (Nanjing11, Balilla, and Nanjing11/Balilla). For example, the S5nS5n genotype within the Nanjing11/Balilla background was produced by crossing S5nS5n-Nanjing11 with S5nS5n-Balilla.

A number of rice receptors were used for transformations, including Balilla, S5iS5i-Balilla, S5nS5n-Balilla, the Nanjing11/Balilla rice hybrid, and another japonica rice, cv Wuxiangjing.

Fertility Survey

All plants were grown at the experimental station of Yangzhou University in 2008 and 2009. To quantify rice spikelet fertility, the percentage of fertile spikelets was measured. Average spikelet fertility was generally determined from three to five plants using two to three panicles from each plant. For each genotype, three experimental replicates were performed.

Expression Profiles of Three S5 Alleles

Various tissues were sampled from Nanjing11, Balilla, and 02428 plants, including immature leaves, young roots, and panicles. Panicles were collected at four developmental stages: (1) panicle extension stage (panicle 5–10 cm in length), (2) booting stage (panicle 10–20 cm in length), (3) heading stage (panicle more than 20 cm in length), and (4) full-bloom stage. Total RNA was extracted using the LiCl-precipitation method (Sambrook and Russell, 2001). After digestion with RNase-free DNase I, 500 ng of RNA was analyzed via one-step real-time RT-PCR using the QuantiTech SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). This analysis was used to determine the level of S5 allele expression in each tissue. Each RNA sample was assayed in triplicate. For a negative control, total RNA without RT was used. The Actin gene was used as a reference, using the primer pair ActinF and ActinR (Supplemental Table S1). Relative amounts of S5 transcripts are presented as 2–ΔCT according to the −ΔCT method described in the Real-Time PCR Applications Guide (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The ΔΔCT value was obtained by subtracting the CT (threshold cycles) number of the Actin gene from that of the S5 allele (ΔΔCT = CTS5 − CTActin). The ΔΔCT value was converted to the linear form in terms of 2−ΔΔCT for statistical analysis.

For differential allelic expression, three parental lines (S5iS5i-Nanjing11, S5nS5n-Nanjing11, and S5jS5j-Balilla) and two hybrid lines (S5iS5j-Nanjing11/Balilla and S5jS5n-Nanjing11/Balilla) were used. To detect relative expression levels of three S5 alleles, RT-PCR products were generated using primers A3F and A3R (Supplemental Fig. S1; Supplemental Table S1), digested with MseI, and subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. The ratio of RT-PCR fragments after MseI digestion corresponded to the differential allelic expression levels.

Detection of AP via Western Blotting

Spikelets from Nanjing11, Balilla, 02428, and Dular were harvested at the four developmental stages described in the previous section, and total protein was extracted using the TCA-acetone precipitation method (Damerval et al., 1986). Protein concentrations were measured using an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies) and adjusted to the same level for each sample. A 30-μg aliquot of protein was subjected to electrophoresis on a 12% SDS-PAGE gel and then electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Amersham Hybond-P; GE Healthcare). Immunoblotting was performed according to Burnette (1981), with optimization. Polyclonal antibodies were purified from the antiserum of rabbits that had been immunized with the peptide SSIGYHRTSRARQ. This sequence was based on the C terminus of AP (Chen et al., 2008). Donkey anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase was used as the secondary antibody (ProteinTech). The membrane was incubated in a nitroblue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate mixture (Amresco) to detect the hybrid signal.

Tissue-Specific Localization of AP

Segments of the S5j and S5n alleles, which encompassed the entire promoter and coding sequence (ending just before the stop codon), were amplified using the primer pair S5JNF and S5JR (for S5j) or S5JNF and S5NR (for S5n; Supplemental Table S1). HindIII and XbaI restriction sites were added to the ends of these forward and reverse primers, respectively. PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) for amplification. S5j and S5n fragments were obtained by digestion with HindIII and XbaI and ligated in frame with GFP coding sequences in vector pMON30049 (Pang et al., 1996). The S5i-GFP and S5n-GFP fragments were then excised with HindIII and EcoRV and cloned into the pCAMBIA1300 binary vector (http://www.cambia.org/daisy/cambia/585) that had been digested with HindIII and SmaI. The resulting constructs (pAj-GFP and pAn-GFP) were then transformed into Balilla via Agrobacterium tumefaciens EHA105. The transgenic plants (together with the receptor Balilla) were grown in the field during the summer of 2008. GFP signals were examined in vegetative and reproductive tissues from both transgenic and nontransgenic plants. Vegetative tissues included roots and leaves (both mature and immature). Reproductive tissues included anthers, ovaries, stigmas, and pollen (collected before, during, and after flowering).

RNAi-Induced Knockdown of S5 Alleles

A 136-bp sequence is present in alleles S5i and S5j but absent from S5n (Ji et al., 2010). This sequence was targeted for RNAi-induced knockdown. Reverse complementary fragments were obtained by PCR amplification using Balilla genomic DNA as the template. The forward (RNAiF1 and RNAiF2) and reverse (RNAiR1 and RNAiR2) primers had BamHI/BglII and SpeI/XbaI sites added to their respective ends (Supplemental Table S1). A 155-bp DNA linker was inserted between the reverse repeat sequences. The entire DNA fragment was then introduced into the binary vector pCAMBIA3301. RNAi sequences were driven by the ubiquitin promoter and terminated by the nitric oxide synthase terminator (Supplemental Fig. S4). The RNAi vector was transformed into a number of rice receptors, including Balilla, S5nS5n-Balilla, S5iS5i-Balilla, and japonica cv Wuxiangjing. The spikelet fertility of transgenic plants was investigated in both the T0 and T1 generations.

Detection of Protein-Protein Interactions via the Yeast Two-Hybrid System

The DupLEX-A Yeast Two Hybrid system (OriGene) was used to determine whether AP isoforms were able to dimerize. Coding sequences of alleles S5j, S5i, and S5n were amplified using PCR. Primer pairs included Y1F-Y1R, Y1F-Y1Ri, and yDf-yDr for S5j, S5i, and S5n, respectively. The predicted signal peptide region was not included in this assay. Forward and reverse primers were tailed with EcoRI and XhoI sites, respectively (Supplemental Table S1). Full-length cDNAs for S5j, S5i, and S5n served as the templates. PCR products were then restriction digested and inserted into bait (pEG202) and prey (pJG4-5) vectors that had also been digested with EcoRI/XhoI. In this way, fused bait and prey proteins were generated in the yeast strain EGY48. Blank bait and prey vectors were cotransformed as a negative control, whereas pEG202-OsFY and pJG4-5-OsFCA-γ, which generate a strong interaction (Lu et al., 2006), were used as positive controls. The filter assay was used to develop the color. Bait-prey interaction levels were determined by comparing the color of the test clones with the color of the positive and negative controls. Blue indicated an interaction, whereas white indicated no interaction. In addition, deep blue color indicated a strong interaction. The clones that turned blue were validated by transferring them to a yeast nitrogen base(Gal)-Ura-His-Trp-Leu medium plate. The LEU2 gene was expressed if interaction happened, which enabled the yeast clone to grow in the selective medium lacking of Leu.

Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace A with either T or G in allele S5j. This was achieved by introducing a T or G in overlapping forward (P1r2-A and P1r2-C) and reverse (P2f-T and P2f-G) primers (Supplemental Table S1). These primers were then used to amplify the targeted S5j region in accordance with the Easy Mutagenesis System (TransGen Biotech). The amplicons were digested with dimethyl terephthalate to remove the nonmutated templates followed by introduction into dimethyl terephthalate-competent cells. Plasmids from positive clones were then purified and validated by sequencing. The resulting constructs contained artificial S5 alleles with either a T or G at the 1,010-bp SNP site, which were named pAsp-T or pAsp-G, respectively. The constructs were transformed into Balilla via Agrobacterium to produce T0 transgenic plants. T0 plants were selfed to generate the T1 generation. Spikelet fertility was investigated for both transgenic and nontransgenic T1 plants.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. The sequence features of the S5 from Dular (WCV), 02428 (WCV), Nanjing 11 (indica), and Balilla (japonica).

Supplemental Figure S2. Tissue-specific localization of AP.

Supplemental Figure S3. Verification of site-directed mutagenesis.

Supplemental Figure S4. Map of the RNAi construct.

Supplemental Table S1. Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elizabeth Bovenmyer for reviewing the manuscript and Drs. Saihua Chen and Rentao Song for technical support. Special thanks go to two reviewers for their constructive suggestions in improving the manuscript.

References

- Bomblies K. (2010) Doomed lovers: mechanisms of isolation and incompatibility in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 61: 109–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnette WN. (1981) ‘Western blotting’: electrophoretic transfer of proteins from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels to unmodified nitrocellulose and radiographic detection with antibody and radioiodinated protein A. Anal Biochem 112: 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TT. (1976) The origin, evolution, cultivation, dissemination, and diversification of Asian and African rice. Euphytica 25: 435–441 [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Ding JH, Ouyang YD, Du HY, Yang JY, Cheng K, Zhao J, Qiu SQ, Zhang XL, Yao JL, et al. (2008) A triallelic system of S5 is a major regulator of the reproductive barrier and compatibility of indica-japonica hybrids in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 11436–11441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Ouyang YD, Wang L, Xie W, Zhang Q. (2009) Apsartic proteases gene family in rice: gene structure and expression, predicted protein feature and phylogenetic relation. Gene 442: 108–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damerval C, de Vienne D, Zivy M, Thiellement H. (1986) Technical improvements in two-dimensional electrophoresis increase the level of genetic variation detected in wheat seedling proteins. Electrophoresis 7: 52–54 [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y. (1957) Origin and evolution of Chinese cultivated rice. Agriculture Journal 8: 243–257 [Google Scholar]

- Dobzhansky T. (1934) Studies on Hybrid Sterility. I. Spermatogenesis in pure and hybrid Drosophila pseudoobscura. Z Zellforch Microsk Anat 21: 169–221 [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Dietrich C, Matsuno M, Li G, Berg H, Xia Y. (2005) An Arabidopsis aspartic protease functions as an anti-cell-death component in reproduction and embryogenesis. EMBO Rep 6: 282–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikehashi H, Araki H. (1986) Genetics of F1 sterility in remote crosses in rice. In Rice Genetics: Proceedings of the First Rice Genetics Symposium. International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), Manila, Philippines, pp 119–130 [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Lu JF, Chao Q, Gu MH, Xu ML. (2005) Delimiting a rice wide-compatibility gene S5n to a 50 kb region. Theor Appl Genet 111: 1495–1503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Q, Lu JF, Chao Q, Zhang Y, Zhang MJ, Gu MH, Xu ML. (2010) Two sequence alterations, a 136 bp InDel and an A/C polymorphic site, in the S5 locus are associated with spikelet fertility of indica-japonica hybrid in rice. J Genet Genomics 37: 57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato S, Kosaka H, Hara K. (1928) On the affinity of rice varieties as shown by fertility of hybrid plants. Bull Sci Fac Agric Kyushu Univ 3: 132–147 [Google Scholar]

- Liang GH, Yan CJ, Yi CD, Zhu LH, Gu MH. (2001) Re-analysis of wide compatibility in rice. [In Chinese with English abstract.] Acta Genet Sin 28: 447–457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu A, Zhang Q, Li H. (1992) Location of a gene for wide-compatibility in the RFLP linkage map. Rice Genet Newsl 9: 134–136 [Google Scholar]

- Liu KD, Wang J, Li HB, Xu CG, Liu AM, Li XH, Zhang Q. (1997) A genome-wide analysis of wide compatibility in rice and the precise location of the S5 locus in the molecular map. Theor Appl Genet 95: 809–814 [Google Scholar]

- Liu KD, Zhou ZQ, Xu CG, Zhang Q, Saghai Maroof MA. (1996) An analysis of hybrid sterility in rice using a diallel cross of 21 parents involving indica, japonica and wide compatibility varieties. Euphytica 90: 275–280 [Google Scholar]

- Long YM, Zhao LF, Niu BX, Su J, Wu H, Chen YL, Zhang QY, Guo JX, Zhuang CX, Mei MT, et al. (2008) Hybrid male sterility in rice controlled by interaction between divergent alleles of two adjacent genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 18871–18876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu BR, Zheng KL, Qian HR, Zhuang JY. (2002) Genetic differentiation of wild relatives of rice as referred by the RFLP analysis. Theor Appl Genet 106: 101–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Xu ZK, Song RT. (2006) OsFY, a homolog of AtFY, encodes a protein that can interact with OsFCA-γ in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 38: 492–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller HJ. (1942) Isolation mechanisms, evolution and temperature. Biol Symp 6: 71–125 [Google Scholar]

- Oka HI. (1988) Origin of Cultivated Rice. Elsevier, Tokyo [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YD, Chen JJ, Ding JH, Zhang Q. (2009) Advances in the understanding of inter-subspecific hybrid sterility and wide-compatibility in rice. Chin Sci Bull 54: 2332–2341 [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang YD, Liu YG, Zhang Q. (2010) Hybrid sterility in plants: stories from rice. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13: 186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang SZ, DeBoer DL, Wan Y, Ye G, Layton JG, Neher MK, Armstrong CL, Fry JE, Hinchee MA, Fromm ME. (1996) An improved green fluorescent protein gene as a vital marker in plants. Plant Physiol 112: 893–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu SQ, Liu KD, Jiang JX, Song X, Xu CG, Li XH, Zhang Q. (2005) Delimitation of the rice wide compatibility gene S5n to a 40-kb DNA fragment. Theor Appl Genet 111: 1080–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Russell DW. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Ed 3. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- Simões I, Faro R, Bur D, Faro C. (2007) Characterization of recombinant CDR1, an Arabidopsis aspartic proteinase involved in disease resistance. J Biol Chem 282: 31358–31365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Zhu C, Zhai H, Wan J. (2005) Mapping segregation distortion loci and quantitative trait loci for spikelet sterility in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genet Res 86: 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Liu KD, Xu CG, Li XH, Zhang Q. (1998) The high level of wide-compatibility of variety Dular has a complex genetic basis. Theor Appl Genet 97: 407–412 [Google Scholar]

- Yan CJ, Liang GH, Zhu LH, Gu MH. (2000) RFLP analysis on wide compatibility genes in rice variety ‘Dular’ of ecotype Aus. [In Chinese with English abstract.] Acta Genet Sin 27: 409–417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagihara S, McCouch SR, Ishikawa K, Ogi Y, Maruyama K, Ikehashi H. (1995) Molecular analysis of the inheritance of the S-5 locus, conferring wide compatibility in indica/japonica hybrids of rice (O. sativa L.). Theor Appl Genet 90: 182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi CD, Yan CJ, Liang GH, Zhu LH, Gu MH. (2001) RFLP analysis of the effect of wide compatibility genes in Aus variety ‘Dular’. [In Chinese with English abstract.] Acta Genet Sin 28: 540–549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]